A Comprehensive Guide to Single-Cell RNA Sequencing in Plant Tissues: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and spatial transcriptomics protocols specifically tailored for plant tissues.

A Comprehensive Guide to Single-Cell RNA Sequencing in Plant Tissues: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and spatial transcriptomics protocols specifically tailored for plant tissues. Aimed at researchers and scientists, it covers foundational principles, from overcoming the unique challenge of plant cell walls to understanding cellular heterogeneity. The content details current methodological approaches, including droplet-based and well-based platforms, and their specific applications in studying plant development, stress responses, and cross-species comparisons. A dedicated troubleshooting section addresses plant-specific optimization challenges, such as protoplasting-induced stress and the choice between single-cell vs. single-nucleus RNA-seq. Finally, the article explores validation techniques and comparative analyses, emphasizing the integration of spatial transcriptomics to preserve crucial contextual information. This guide serves as an essential resource for leveraging scRNA-seq to advance plant biology and synthetic biology applications.

Understanding the Foundation: Why Single-Cell Resolution is Revolutionizing Plant Biology

The advent of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has fundamentally transformed transcriptomic studies, enabling the resolution of cellular heterogeneity that was previously obscured by bulk RNA-seq methodologies. While bulk RNA-seq provides a population-averaged gene expression profile for a tissue or cell population, scRNA-seq delineates the transcriptional landscape of individual cells, offering unprecedented insights into cell-type diversity, rare cell populations, and developmental trajectories [1]. This paradigm shift is particularly impactful in plant biology, where complex tissues exhibit remarkable cellular specialization for functions ranging from nutrient uptake to environmental adaptation [2] [3]. The transition from bulk to single-cell resolution has revealed previously unappreciated dimensions of biological complexity, allowing researchers to characterize novel cell types, map developmental pathways, and understand how individual cells respond to environmental stimuli [4] [1].

Technical Foundations: Key Methodological Differences

Fundamental Workflow Comparisons

The core distinction between bulk and single-cell RNA-seq lies in their experimental workflows and resulting data outputs. Bulk RNA-seq analyzes RNA extracted from thousands to millions of cells simultaneously, yielding a composite expression profile that represents the average transcriptome across all cells in the sample [5] [6]. In contrast, scRNA-seq maintains transcriptomic information from individual cells throughout the process, enabling the association of expression patterns with specific cell identities [5].

Table 1: Core Differences Between Bulk and Single-Cell RNA-seq

| Feature | Bulk RNA-seq | Single-Cell RNA-seq |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Population average | Individual cell level |

| Cost per Sample | Lower (~1/10 of scRNA-seq) | Higher |

| Data Complexity | Lower | Higher |

| Cell Heterogeneity Detection | Limited | High |

| Rare Cell Type Detection | Limited | Possible |

| Gene Detection Sensitivity | Higher per sample | Lower per cell |

| Sample Input Requirement | Higher | Lower |

| Technical Challenges | Limited heterogeneity information | Data sparsity, dropout events |

Plant-Specific Technical Considerations

In plant systems, scRNA-seq presents unique technical challenges primarily due to the presence of rigid cell walls, which require enzymatic digestion to release protoplasts for analysis [2] [3]. This protoplasting process can induce cellular stress responses that alter gene expression patterns, potentially confounding results [4]. Recent advances have addressed this limitation through single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq), which isolates nuclei instead of whole cells, thereby avoiding enzymatic digestion and enabling the profiling of cell types with recalcitrant walls, such as xylem vessels [2] [3]. For high-throughput applications, droplet-based methods like 10x Genomics have been widely adopted, allowing for the parallel processing of thousands of plant cells [4] [3].

Applications in Plant Biology: Resolving Cellular Complexity

Cell Atlas Construction and Novel Cell-Type Identification

scRNA-seq has enabled the construction of comprehensive cell atlases for model plants and crops, systematically cataloging cell types and their transcriptional signatures. In rice roots, integration of scRNA-seq with spatial transcriptomics has validated cell-type-specific markers and revealed how outer root tissues adapt to soil environments [4]. Similar approaches in Arabidopsis have resolved the complex cellular composition of roots, leaves, and meristems, identifying rare cell populations and transitional states undetectable by bulk methods [2].

Developmental Trajectory Reconstruction

A key application of scRNA-seq is pseudotime analysis, which computationally orders cells along developmental trajectories based on transcriptional similarities [2]. This approach has elucidated differentiation pathways in plant systems, including the development of root epidermis and lateral root primordia in Arabidopsis, and has traced the lineage relationships in maize anthers and shoot apices [2]. Unlike bulk RNA-seq, which requires physical separation of tissues at different stages, scRNA-seq can reconstruct continuous developmental processes from a single sampled time point.

Environmental Response at Cellular Resolution

scRNA-seq has revealed how different cell types within plant organs exhibit specialized responses to environmental conditions. Research on rice roots exposed to soil compaction stress demonstrated that outer root tissues (epidermis, exodermis, sclerenchyma) show the most pronounced transcriptional changes, particularly in genes related to cell wall remodeling and barrier formation [4]. Bulk RNA-seq of whole root tips would have masked these cell-type-specific responses, highlighting scRNA-seq's unique ability to resolve spatial patterns of environmental adaptation [4].

Table 2: Representative scRNA-seq Applications in Plant Research

| Application | Plant Species | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Root Cell Atlas | Rice | Identified cell-type-specific responses to soil growth conditions | [4] |

| Developmental Trajectory | Arabidopsis | Reconstructed epidermal differentiation and root hair formation | [2] |

| Stem Cell Niche | Maize | Characterized shoot apical meristem cell populations | [2] |

| Environmental Adaptation | Rice | Revealed compaction stress responses in specific root tissues | [4] |

| Comparative Analysis | Multiple species | Enabled cross-species comparison of cell-type expression | [2] |

Experimental Protocol: Plant Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Workflow

Sample Preparation and Protoplast Isolation

Successful plant scRNA-seq begins with optimal sample preparation. For protoplast-based approaches:

- Tissue Collection: Harvest fresh tissue from desired plant organs (root tips, leaves, etc.) and immediately place in appropriate buffer to prevent RNA degradation.

- Cell Wall Digestion: Incubate tissue in enzyme solution (e.g., cellulase, macerozyme) optimized for the specific plant species and tissue type. Chemical fixation prior to digestion can improve protoplast yields for some difficult tissues [2].

- Protoplast Purification: Filter the digestate through mesh filters (30-70 μm) to remove undigested debris, then concentrate viable protoplasts by centrifugation through density gradients.

- Quality Assessment: Determine protoplast viability and concentration using microscopy and cell counting. High viability (>80%) is essential for successful library preparation [3].

For tissues with recalcitrant cell walls or when protoplasting-induced stress is a concern, nuclei isolation provides an alternative:

- Nuclei Extraction: Homogenize frozen or fresh tissue in nuclei isolation buffer, then filter and concentrate nuclei via centrifugation.

- Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS): Optionally sort nuclei based on size, DNA content, or fluorescent markers to enrich for specific cell populations [3].

Library Preparation and Sequencing

Current best practices for plant scRNA-seq library preparation typically employ droplet-based partitioning systems:

- Single-Cell Partitioning: Use a microfluidic platform (e.g., 10x Genomics Chromium) to encapsulate individual cells/nuclei into oil-emulsion droplets containing barcoded beads.

- Reverse Transcription: Within each droplet, cell lysis releases RNA, which is captured by poly-dT primers on barcoded beads containing Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) and cell barcodes [3].

- cDNA Amplification and Library Construction: Reverse transcription produces barcoded cDNA, which is then amplified and prepared for sequencing following platform-specific protocols.

- Sequencing: Typically performed on Illumina platforms with recommended read lengths (e.g., 28bp Read1, 10bp i7 index, 90bp Read2) to cover both cell barcodes/UMIs and transcript sequences.

Computational Analysis Pipeline

The analysis of scRNA-seq data requires specialized computational approaches distinct from bulk RNA-seq:

- Quality Control and Preprocessing: Process raw sequencing data with tools like Cell Ranger or STARsolo to generate gene expression matrices, then filter out low-quality cells based on UMI counts, gene detection, and mitochondrial content [7].

- Normalization and Batch Correction: Apply methods like SCnorm or regularized negative binomial regression to normalize counts and correct for technical variability between batches [8] [7].

- Feature Selection and Dimensionality Reduction: Identify highly variable genes, then reduce dimensionality using principal component analysis (PCA) followed by visualization with UMAP or t-SNE [8] [7].

- Cell Clustering and Annotation: Cluster cells based on transcriptional similarities using graph-based methods, then annotate cell types using known marker genes and reference datasets [7].

- Downstream Analysis: Perform trajectory inference, differential expression, and cell-cell communication analysis to extract biological insights [7].

Essential Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Plant scRNA-seq

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Wall Digestion Enzymes | Cellulase, Macerozyme, Pectolyase | Degrade plant cell walls to release protoplasts |

| Nuclei Isolation Buffers | Nuclei EZ Lysis Buffer, Sucrose gradients | Extract intact nuclei for snRNA-seq |

| Viability Stains | Fluorescein diacetate (FDA), Propidium iodide | Assess cell/nuclei viability before processing |

| Single-Cell Platform Kits | 10x Genomics Chromium Next GEM Kits | Partition single cells and barcode transcripts |

| Library Preparation Kits | SMART-seq2, CEL-seq2 reagents | Amplify and prepare cDNA for sequencing |

| Sequence Capture Beads | Barcoded gel beads with UMIs | Capture mRNA and assign cellular barcodes |

Computational Toolkit

- Processing Pipelines: Cell Ranger (10x Genomics), STARsolo, Kallisto-Bustools [7] [3]

- Quality Control: FastQC (read quality), Scrublet (doublet detection) [7]

- Downstream Analysis: Seurat (R-based), Scanpy (Python-based) [7] [3]

- Trajectory Inference: Monocle, PAGA [2]

- Spatial Mapping: Molecular Cartography, integration with spatial transcriptomics [4]

The paradigm shift from bulk to single-cell RNA sequencing has fundamentally expanded our ability to resolve cellular heterogeneity in plant systems. By enabling the characterization of cell-type-specific responses to development and environment, scRNA-seq has revealed previously inaccessible dimensions of plant biology. While challenges remain—including the high cost per cell, technical artifacts from protoplasting, and computational complexity—ongoing methodological improvements continue to enhance accessibility and data quality [2] [3]. The integration of scRNA-seq with emerging spatial transcriptomics and multi-omics technologies promises to further advance our understanding of plant development, stress adaptation, and cellular function, ultimately accelerating crop improvement and sustainable agriculture.

Key Technical Advancements Driving Plant scRNA-seq Adoption

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has emerged as a revolutionary technology in plant biology, enabling the investigation of cellular heterogeneity, gene regulatory networks, and developmental processes at unprecedented resolution. Unlike traditional bulk RNA sequencing, which averages gene expression across thousands of cells, scRNA-seq reveals the unique transcriptional profiles of individual cells, uncovering rare cell types and dynamic cellular states that were previously masked [1]. The adoption of this technology in plant systems has accelerated due to a series of key technical advancements addressing plant-specific challenges, particularly the presence of rigid cell walls. This application note details these critical innovations, providing structured protocols and resources to guide researchers in implementing cutting-edge plant scRNA-seq methodologies.

Critical Technical Advancements

Sample Preparation Breakthroughs

Sample preparation remains a pivotal stage in plant scRNA-seq, largely due to the challenge of disrupting cell walls without compromising cellular RNA.

- Protoplast vs. Nuclei Isolation: Two primary approaches have been developed to overcome the cell wall barrier. Protoplast isolation involves enzymatic digestion of the cell wall to release intact cells, providing comprehensive transcriptome data including cytoplasmic mRNAs [3] [9]. However, this process can induce stress responses that alter gene expression [3]. As a robust alternative, single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) isolates nuclei, circumventing the need for cell wall digestion. This method is particularly advantageous for tissues with robust cell walls (e.g., xylem), frozen samples, and studies where minimizing technical artifacts is paramount [10] [3] [9].

- Novel Instrument-Free Platforms: The recent introduction of RevGel-seq, a method adapted from animal studies, represents a significant breakthrough. This technology operates using cell-barcoded bead complexes and eliminates the need for specialized single-cell RNA instruments, providing greater flexibility and convenience in sample processing [11].

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Sample Preparation Methods for Plant scRNA-seq

| Method | Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protoplast Isolation | Enzymatic digestion of cell wall to release intact cells. | Captures full cellular transcriptome (cytoplasmic & nuclear RNA). | Can induce stress responses; biased against hard-to-digest cell types. | Tissues with weak cell walls (e.g., leaves, roots); studies requiring full-length transcripts. |

| Nucleus Isolation (snRNA-seq) | Extraction and sequencing of RNA from individual nuclei. | Avoids enzymatic stress; works with frozen/challenging tissues. | Misses cytoplasmic transcripts; may capture unprocessed RNA. | Lignified tissues, archived samples, and when profiling nuclear transcripts is sufficient. |

| RevGel-seq | Instrument-free partitioning using cell-barcoded bead complexes. | No need for specialized equipment; highly flexible and efficient. | Relatively new method in plants; protocol still being optimized. | High-throughput studies where access to microfluidic instruments is limited. |

Advanced Library Construction & Sequencing Technologies

Advancements in library construction have dramatically increased throughput, quantitative accuracy, and scalability.

- High-Throughput Droplet-Based Systems: Platforms like 10x Genomics Chromium and BD Rhapsody enable massively parallel sequencing by encapsulating thousands of individual cells or nuclei in droplets or microwells along with barcoded beads. This allows for the efficient processing of complex plant tissues and the identification of rare cell populations [3] [12].

- Cost-Effective Combinatorial Indexing: Methods like SPLiT-seq (Split-Pool Ligation-based Transcriptome sequencing) offer a highly scalable and affordable solution. This technique uses combinatorial barcoding in solution without the need for physical partitioning of cells, enabling the profiling of hundreds of thousands of fixed cells or nuclei in a single experiment with minimal equipment [9].

- Molecular Barcoding for Precision: The widespread adoption of Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) has been crucial for accurate quantification. UMIs tag each mRNA molecule during reverse transcription, allowing bioinformatic tools to correct for amplification biases, thereby transforming scRNA-seq into a truly quantitative tool [12].

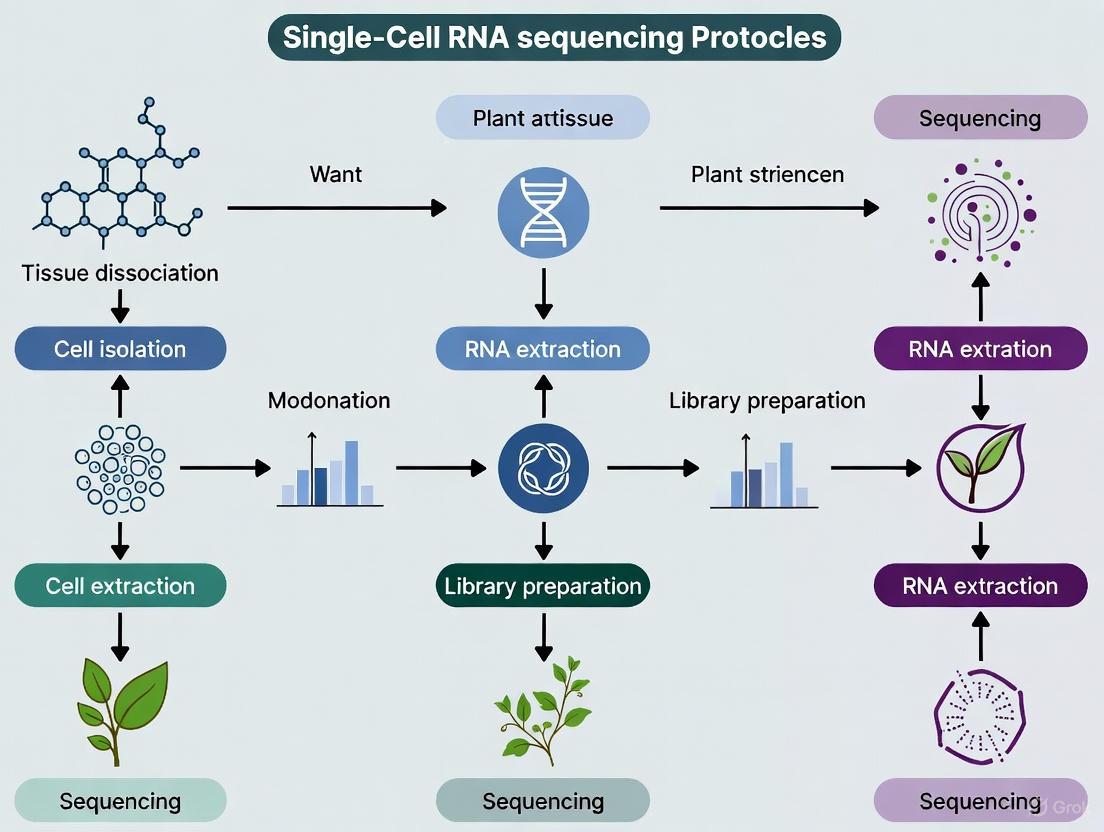

The following diagram illustrates the core workflows for the two main sample preparation paths leading to library construction and sequencing.

Integration with Spatial Transcriptomics

A transformative advancement in the field is the coupling of scRNA-seq with spatial transcriptomics. While scRNA-seq reveals cellular heterogeneity, it loses the native spatial context of cells within tissues. Spatial transcriptomics technologies, such as Slide-seq and Stereo-seq, map gene expression directly onto tissue sections, preserving this critical information [10] [9].

The paired application of these techniques was powerfully demonstrated in a foundational atlas of the Arabidopsis thaliana life cycle. This study integrated single-nucleus data with spatial maps to validate newly identified cell-type-specific markers and uncover spatially regulated expression patterns, such as those governing the development of the apical hook structure in seedlings [10] [13]. This integration is essential for understanding cell-cell interactions and the spatial organization of biological processes.

Sophisticated Computational Tools & Databases

The massive, complex datasets generated by scRNA-seq necessitate robust computational tools and centralized resources.

- Analytical Pipelines: Seurat (R-based) and SCANPY (Python-based) are the two most widely adopted toolkits for single-cell data analysis. They provide comprehensive workflows for quality control, normalization, clustering, and differential expression analysis [3].

- Specialized Plant Databases: The development of plant-specific databases has been instrumental in annotating and interpreting data.

- PlantscRNAdb and scPlantDB serve as curated repositories, hosting data from multiple plant species and providing tools for analyzing marker genes and exploring cell types [11].

- Plant Cell Marker DataBase contains a vast collection of known cell marker genes, which is critical for the accurate annotation of cell clusters identified in scRNA-seq experiments [11].

Table 2: Key Computational Tools and Databases for Plant scRNA-seq Analysis

| Tool/Database | Function | Key Features | Applicability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seurat | Comprehensive R toolkit for scRNA-seq data analysis. | Data integration, clustering, visualization, differential expression. | General-purpose analysis, suitable for users proficient in R. |

| SCANPY | Python-based toolkit for analyzing single-cell gene expression data. | Scalable to very large datasets; integrates with machine learning libraries. | General-purpose analysis, suitable for users proficient in Python. |

| Cell Ranger | Bioinformatic pipeline from 10x Genomics for processing raw sequencing data. | Generates expression matrices from FASTQ files; standard for 10x data. | Essential first step for data generated on the 10x Genomics platform. |

| scPlantDB | A comprehensive database for plant single-cell transcriptomes. | Hosts data from ~2.5 million cells across 17 plant species. | Cross-species comparison and marker gene discovery. |

| Plant Cell Marker DataBase | Repository of known plant cell marker genes. | Contains 81,117 cell marker genes across 263 cell types. | Annotation and validation of cell clusters. |

Emerging Frontiers & Multi-Omics Integration

The field is rapidly moving towards multi-omics approaches at the single-cell level. A groundbreaking proof-of-concept study demonstrated the simultaneous measurement of the metabolome and transcriptome from the same single plant cell. This multiplexing approach, applied to the medicinal plant Catharanthus roseus, enables direct correlation of gene expression with metabolite levels, offering unparalleled insights into the biosynthetic pathways of valuable natural products [14]. The logical flow from data generation to biological insight in such integrated studies is outlined below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Successful implementation of plant scRNA-seq relies on a suite of critical reagents and materials.

- Cell Wall Digesting Enzymes: Cellulases and pectolyases are essential for protoplast isolation. The specific cocktail and incubation time must be optimized for each plant species and tissue type [3] [11].

- Nuclei Extraction Buffers: Specifically formulated lysis buffers (e.g., containing NP-40 or Triton detergents) are required to release nuclei while maintaining nuclear membrane integrity and RNA quality [3].

- Barcoded Beads: Commercial kits (e.g., from 10x Genomics) provide beads coated with oligonucleotides containing poly(dT) sequences, cell barcodes, and UMIs, which are critical for capturing mRNA and tagging its cell of origin [3] [12].

- Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorter (FACS): While not a reagent, this instrument is crucial for purifying nuclei or protoplasts after isolation, removing debris and ensuring a high-quality input sample for library preparation [3] [9].

- Reverse Transcriptase and Template-Switching Oligos: High-efficiency reverse transcriptases (e.g., with template-switching activity) are used in many protocols like SMART-seq2 to ensure full-length cDNA synthesis and efficient amplification [3] [12].

The adoption of scRNA-seq in plant biology has been propelled by a concerted series of technical innovations. Breakthroughs in sample preparation, such as snRNA-seq and RevGel-seq, have overcome the primary hurdle of the plant cell wall. Concurrently, advancements in high-throughput library construction, the integration of spatial context, and the development of powerful computational resources have created a mature and powerful toolkit. As the field continues to evolve, the integration of scRNA-seq with other omics modalities, such as metabolomics and epigenomics, promises to further deepen our understanding of plant development, stress responses, and the biosynthesis of valuable compounds, ultimately accelerating crop improvement and biotechnology applications.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized developmental biology by enabling researchers to investigate cellular heterogeneity at an unprecedented resolution. In plant biology, where cell fate is highly plastic and influenced by complex interactions between lineage, position, and the environment, this technology is particularly transformative [15]. Traditionally, plant cell types were categorized based on their function, location, morphology, and lineage history [15]. However, scRNA-seq allows scientists to move beyond these static classifications by capturing the complete transcriptome of individual cells, revealing not only previously hidden cell types but also transient cellular states that underlie developmental processes and environmental responses [15] [12]. This application note details the core principles and methodologies through which scRNA-seq uncovers this hidden diversity, with a specific focus on applications in plant tissue research.

Core Principles of Cell Type Identification

The power of scRNA-seq to reveal hidden cell types rests on several foundational principles that reinterpret traditional concepts of cellular identity through a high-resolution, data-driven lens.

From Classical Definitions to Transcriptomic Clustering

Classical plant histology defines cell types like parenchyma, collenchyma, and sclerenchyma based on cell wall morphology, and specialized cells like stomatal guard cells based on their function, location, and distinctive lineage [15]. scRNA-seq introduces a complementary, quantitative framework where cell types are identified as clusters of cells with similar gene expression profiles [15]. This approach can validate known cell types through established marker genes and, more importantly, reveal previously uncharacterized or rare cell populations based on unique transcriptional signatures [10].

Distinguishing Cell Type from Cell State

A critical principle in single-cell biology is the distinction between cell type and cell state [15].

- Cell Type: Represents a more stable identity, often defined by a core regulatory program.

- Cell State: Reflects transient, dynamic conditions within a cell type, influenced by processes like the cell cycle, metabolic activity, or response to immediate signals [15]. scRNA-seq captures this complexity, showing that transcriptomes are dynamic. Researchers must often computationally account for confounding factors like cell cycle phase to reveal the underlying stable identity of a cell [15].

The Conceptual Framework of Cell Fate

The journey of a cell is often visualized using Waddington's landscape metaphor, where a totipotent cell (a ball at the top of a hill) rolls down through branching valleys, each representing a trajectory toward a specific, mature cell type [15]. scRNA-seq allows researchers to map these trajectories in high dimension, observing how cells progress through developmental pathways and how signals can push cells between different fates [15]. In plants, where cell fate is highly malleable, this principle is key to understanding processes like de-differentiation and regeneration [15].

Key Methodologies and Experimental Workflows

Implementing scRNA-seq to uncover hidden cell types requires a carefully optimized workflow, from tissue preparation to sequencing.

Single-Cell Isolation and Library Preparation

The initial and most critical wet-lab step involves isolating viable single cells or nuclei from complex plant tissues. This can be challenging for plant cells due to their rigid cell walls. Single-nucleus RNA-seq (snRNA-seq) is a valuable alternative when tissue dissociation is difficult or for frozen samples [12] [10]. Following isolation, the RNA from individual cells is barcoded, converted to cDNA, and amplified. Key methodological choices include:

- Full-length transcript protocols (e.g., Smart-Seq2), which are advantageous for isoform analysis.

- 3' or 5' end counting protocols (e.g., Drop-Seq, 10x Genomics), which enable higher throughput and lower cost per cell, making them ideal for profiling complex tissues and tumors [12]. The use of Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) is critical during reverse transcription to label each mRNA molecule quantitatively, mitigating amplification biases and enabling accurate digital counting of transcripts [12].

From Raw Data to a Cell-Feature Matrix

Sequencing transforms mRNA into a digital format, producing raw data in FASTQ files [16]. Primary computational analysis involves:

- Alignment: Mapping sequencing reads to a reference genome to identify the genes present.

- UMI Counting: Counting the number of unique UMI-gene combinations per cell barcode to generate a cell-feature matrix [16]. This matrix, with genes as rows and cells as columns, forms the quantitative foundation for all subsequent analyses. Quality control (QC) is performed to filter out low-quality cells or doublets [16].

Data Analysis and Annotation Workflow

The analysis of the cell-feature matrix involves several steps designed to reduce dimensionality and extract biological meaning, as outlined in the workflow below.

Diagram 1: Core scRNA-seq Data Analysis Workflow (76 characters)

- Dimensionality Reduction: Techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) condense thousands of gene dimensions into a manageable number of principal components that capture the most significant variance in the dataset [16].

- Clustering and Visualization: Cells are computationally grouped into clusters based on similar gene expression profiles using algorithms like K-means or graph-based clustering [16]. These clusters are then visualized in 2D or 3D space using methods like t-SNE or, more commonly, UMAP, which help researchers intuitively see potential cell populations [16].

- Cell Type Annotation: Clusters are annotated by identifying differentially expressed genes (DEGs) that serve as potential markers. Annotation leverages known marker genes from literature and databases [10]. Advanced platforms now use AI-powered tools to automate this process by comparing cluster gene expression against large reference atlases [17].

- Spatial Validation: For plant biology, pairing snRNA-seq with spatial transcriptomics is a powerful method for validation. It allows researchers to visualize the expression of newly discovered marker genes within the native context of the tissue, confirming both the identity and location of the cell type [10].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Tools

Successful scRNA-seq research relies on a suite of specialized reagents, tools, and software. The table below catalogs key solutions for a plant single-cell genomics pipeline.

Table 1: Research Reagent and Tool Solutions for scRNA-seq

| Category | Item | Function | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Reagents | Nuclei Isolation Kit | Isolates nuclei for snRNA-seq from tough or frozen plant tissues. | Critical for plant samples [10]. |

| scRNA-seq Library Prep Kit | Creates barcoded, sequencing-ready libraries from single cells. | 10x Genomics Chromium, Parse Biosciences [17]. | |

| UMI Reagents | Labels individual mRNA molecules for accurate transcript counting. | Integrated into most modern kits [12]. | |

| Computational Tools | Alignment & Matrix Tool | Processes FASTQ files, aligns reads, and generates cell-feature matrix. | Cell Ranger (10x Genomics) [16]. |

| Analysis Platform | Provides end-to-end environment for clustering, DGE, and visualization. | Seurat, Scanpy, Nygen, Partek Flow [17]. | |

| Visualization Software | Enables interactive exploration of clustered data. | Loupe Browser, BBrowserX [17]. | |

| Reference Databases | Cell Atlas | A curated collection of scRNA-seq datasets used for automated cell annotation. | BioTuring Single-Cell Atlas [17]. |

| Spatial Transcriptomic Atlas | Provides spatial gene expression patterns for validating scRNA-seq clusters. | As generated for Arabidopsis [10]. |

Case Study: A Single-Cell Atlas of the Arabidopsis Life Cycle

A landmark 2025 study in Nature Plants exemplifies the power of this integrated approach [10]. Researchers generated a single-nucleus and spatial transcriptomic atlas spanning the entire Arabidopsis life cycle, from seed to silique, encompassing over 400,000 nuclei.

- Objective: To create a comprehensive map of cellular identities and states throughout plant development [10].

- Methodology: The team applied paired single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) and spatial transcriptomics to ten developmental stages. Cluster annotation was guided by known marker genes and systematically validated with spatial transcriptomics [10].

- Outcome: The study confidently annotated 75% of the 183 identified cell clusters. It revealed striking molecular diversity, identified organ-specific heterogeneity, and uncovered numerous previously uncharacterized cell-type-specific markers [10]. For instance, they validated new epidermal markers with specific spatial localizations in the apical hook and cotyledons of seedlings, demonstrating how scRNA-seq can reveal subtle variations in cell states within a broad cell type [10].

The logical flow of this case study, from experimental design to biological insight, is summarized in the diagram below.

Diagram 2: Arabidopsis Case Study Workflow (48 characters)

scRNA-seq, particularly when integrated with spatial transcriptomics, has fundamentally changed the toolkit for discovering and defining cell types and states in plant research. By moving from static, morphology-based classifications to a dynamic, high-resolution understanding of transcriptional landscapes, researchers are now equipped to unravel the hidden complexity of plant development, physiology, and environmental adaptation. The protocols, analytical frameworks, and toolkits detailed in this application note provide a roadmap for leveraging these powerful technologies to drive discovery in plant biology.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized biology by enabling the characterization of gene expression at the ultimate resolution—the individual cell. While this technology has transformed biomedical research, its application in plant systems presents distinct challenges rooted in fundamental structural differences between plant and animal cells [1] [9]. The plant cell wall, a rigid structural component absent in animal cells, represents the most significant technical barrier to single-cell analysis in plants. This complex matrix of cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectin requires specialized degradation protocols that can induce cellular stress responses and alter native gene expression patterns [9]. Beyond the physical barrier, plants exhibit remarkable cellular complexity with highly specialized cell types—from trichoblasts and atrichoblasts in root epidermis to diverse vascular cell types—each playing specific roles in development, nutrient uptake, and environmental adaptation [4] [9].

Understanding this cellular heterogeneity is crucial for advancing plant biology, synthetic biology, and agricultural biotechnology. scRNA-seq provides unprecedented opportunities to uncover novel cell types, delineate developmental trajectories, and identify key regulatory genes controlling important agronomic traits [18]. However, standard scRNA-seq protocols developed for animal cells require significant modifications to address plant-specific challenges. This application note details current methodologies, protocols, and analytical frameworks specifically adapted for plant single-cell transcriptomics, providing researchers with practical guidance for navigating the unique complexities of plant cellular systems.

Methodological Approaches for Plant Single-Cell Transcriptomics

Cell Isolation Strategies: Protoplasting versus Nuclear Isolation

The initial step of single-cell isolation presents the primary bottleneck in plant scRNA-seq workflows. Two predominant strategies have emerged to address the cell wall challenge: protoplasting and single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq). Each approach offers distinct advantages and limitations that must be carefully considered based on research objectives and plant species.

Protoplasting involves enzymatic digestion of the cell wall to release intact protoplasts. This method provides comprehensive transcriptome coverage including both nuclear and cytoplasmic RNAs, making it ideal for studying processes involving mature transcripts and cytoplasmic events [9]. However, protoplasting is time-consuming, induces cellular stress responses that can alter gene expression, and presents technical difficulties for tissues with robust secondary cell walls [4] [9]. Recent studies have identified protoplasting-induced genes that should be excluded from analysis to ensure biological relevance [4].

Single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) has emerged as a valuable alternative that bypasses cell wall digestion. By isolating and sequencing RNA from individual nuclei, snRNA-seq eliminates protoplasting-induced stress and enables analysis of difficult-to-dissociate tissues or preserved specimens [9]. While snRNA-seq captures fewer transcripts and may include more immature RNA molecules, studies demonstrate strong correlation with cytoplasmic expression patterns for cell type classification [9]. This method is particularly advantageous for frozen samples, tissues with complex structures, and cross-species comparative studies [9].

Table 1: Comparison of Cell Isolation Methods for Plant scRNA-seq

| Method | Advantages | Limitations | Ideal Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protoplasting | Comprehensive transcriptome coverage (nuclear + cytoplasmic RNA); Captures mature transcripts | Induces cellular stress; Technically challenging; Species/tissue-dependent efficiency | Studies requiring full transcriptome; Dynamic processes involving cytoplasmic regulation |

| Single-Nucleus RNA-seq | Avoids protoplasting stress; Works with frozen/preserved samples; Applicable to diverse tissue types | Misses cytoplasmic RNA; May capture immature transcripts; Lower transcript capture efficiency | Difficult-to-dissociate tissues; Large-scale studies; Frozen archives; Cross-species comparisons |

| SPLiT-seq | No physical single-cell isolation; Extremely high throughput; Fixed cells/nuclei; Low cost per cell | Lower sequencing depth; Complex barcode design | Massive-scale studies; Limited starting material; Budget-constrained projects |

Experimental Workflow Design

The following diagram illustrates the key decision points in designing a plant single-cell transcriptomics study, from sample preparation through data integration:

Diagram Title: Plant scRNA-seq Experimental Workflow Decision Tree

High-Throughput Sequencing Platforms

Multiple sequencing platforms have been adapted for plant single-cell studies, each offering different advantages in throughput, cost, and data quality. Droplet-based methods like 10x Genomics Chromium enable profiling of thousands of cells simultaneously, making them ideal for capturing rare cell populations [9]. Microwell-based platforms such as BD Rhapsody provide efficient mRNA capture but may be limited by cell size restrictions [9]. For full-length transcript coverage, plate-based methods like Smart-Seq2 offer enhanced sensitivity for detecting low-abundance transcripts but with lower throughput [19].

More recently, split-pool ligation-based approaches like SPLiT-seq have emerged as cost-effective alternatives that enable massive parallel sequencing without requiring specialized equipment [9]. This method uses combinatorial indexing to label cells through successive rounds of splitting and pooling, making it particularly suitable for large-scale studies with budget constraints [9]. The choice of platform should be guided by research objectives, tissue type, and available resources, with throughput, sensitivity, and cost being primary considerations.

Specialized Protocols for Plant Tissues

Protoplast Isolation Protocol

Principle: Enzymatic degradation of cell walls to release intact protoplasts for single-cell sequencing.

Materials:

- Enzyme solution: Cellulase (1.5%), Macerozyme (0.4%), Pectolyase (0.1%)

- Osmoticum: Mannitol (0.4-0.6 M) to maintain osmotic balance

- Protoplast washing buffer: Without enzymes

- Filtration system: 40-70 μm mesh filters

- Centrifuge with swinging bucket rotor

Detailed Protocol:

Tissue Preparation: Harvest fresh plant tissue (100-200 mg) and slice into 0.5-1 mm strips using sharp razor blades. Immediate processing is critical to prevent stress responses.

Enzymatic Digestion: Incubate tissue slices in 10 mL enzyme solution for 3-6 hours at 25°C with gentle shaking (40-60 rpm). Digestion time varies by species and tissue type.

Protoplast Release: Gently agitate digested tissue using wide-bore pipettes. Monitor release microscopically.

Filtration and Washing: Filter through 40 μm mesh, then 70 μm mesh to remove debris. Centrifuge filtrate at 100 x g for 5 minutes.

Viability Assessment: Determine protoplast viability (>85% required) using Trypan Blue exclusion.

Library Preparation: Resuspend protoplasts at 1,000-1,200 cells/μL for 10x Genomics or equivalent platform loading.

Critical Considerations:

- Include protoplasting-induced genes in downstream analysis exclusion [4]

- Process controls in parallel to identify digestion-specific artifacts

- Optimize enzyme concentrations for specific tissue types

Single-Nucleus RNA Sequencing Protocol

Principle: Isolation of nuclei for sequencing, bypassing cell wall digestion and associated stress responses.

Materials:

- Nuclei isolation buffer: 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl₂, 0.1% Nonidet P-40, 1% BSA, 10% glycerol

- Dounce homogenizer with loose and tight pestles

- Sucrose cushion: 30% sucrose in nuclei isolation buffer without detergent

- Fluorescence-activated nuclei sorting (FANS) equipment

Detailed Protocol:

Tissue Fixation/Homogenization: Flash-freeze tissue in liquid N₂. Grind to fine powder under liquid N₂. Transfer to Dounce homogenizer with 10 mL ice-cold nuclei isolation buffer.

Homogenization: Perform 10-15 strokes with loose pestle, then 5-10 strokes with tight pestle. Check nuclei release microscopically.

Filtration and Purification: Filter through 40 μm mesh. Layer filtrate over sucrose cushion. Centrifuge at 1,000 x g for 10 minutes.

Nuclei Sorting: Resuspend pellet in 1 mL nuclei isolation buffer without detergent. Sort nuclei using FANS based on DAPI fluorescence.

Quality Control: Assess nuclei integrity microscopically. Count using hemocytometer.

Library Preparation: Load 5,000-10,000 nuclei per reaction for 10x Genomics or equivalent platform.

Advantages: Compatible with frozen archives; minimal technical artifacts; applicable across diverse species [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Plant Single-Cell Transcriptomics

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Wall Digestion Enzymes | Cellulase R-10, Macerozyme R-10, Pectolyase Y-23 | Protoplast isolation; Concentration optimization required for different species/tissues |

| Osmotic Stabilizers | Mannitol (0.4-0.6 M), Sorbitol, KCl | Maintain osmotic balance during protoplasting; Critical for viability |

| Nuclei Isolation Reagents | Nonidet P-40, Triton X-100, Sucrose cushions | Nuclear membrane integrity; Concentration optimization minimizes lysis |

| Viability Stains | Trypan Blue, Fluorescein Diacetate (FDA), Propidium Iodide | Quality control; FDA preferred for protoplasts |

| Single-Cell Platforms | 10x Genomics Chromium, BD Rhapsody, Smart-Seq2 | Throughput/sensitivity trade-offs; 10x most common for plant studies |

| Spatial Transcriptomics | 10x Visium, Slide-seq, Stereo-seq | Spatial context preservation; Stereo-seq offers 500 nm resolution [9] |

| Analysis Frameworks | scPlant, Seurat, SCANVI, CellHint | scPlant specifically designed for plant data [20] |

Data Analysis Frameworks for Plant Single-Cell Data

The scPlant Framework

The scPlant framework represents a significant advancement for analyzing plant single-cell transcriptomic data, providing specialized tools addressing plant-specific analytical challenges [20]. This versatile framework supports the entire analytical workflow from quality control to cell type annotation and trajectory inference, incorporating algorithms optimized for plant-specific characteristics including high sparsity levels and unique cell type markers.

Key features include specialized normalization methods accounting for plant cell wall-induced artifacts, integrated databases of known plant cell type markers, and visualization tools adapted for plant morphological structures. The framework has been successfully applied across diverse species including Arabidopsis, rice, maize, and wheat, demonstrating its broad applicability in plant research [20].

Spatial Transcriptomics Integration

Integrating scRNA-seq with spatial transcriptomic technologies has proven particularly valuable for plant studies, enabling precise mapping of gene expression to tissue context [4] [13]. Spatial transcriptomics methods like Stereo-seq achieve resolutions as fine as 500 nm, allowing distinction of highly similar cell types in complex plant tissues [9]. This integration is essential for validating computational predictions and understanding tissue organization principles.

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between different analytical approaches and the biological insights they enable:

Diagram Title: Plant scRNA-seq Data Analysis Pathways

Applications and Case Studies

Soil Adaptation in Rice Roots

A recent landmark study applied scRNA-seq to investigate how rice roots adapt to soil conditions at single-cell resolution [4]. Researchers compared root transcriptomes from gel-grown versus soil-grown plants, revealing major expression changes specifically in outer root cell types related to nutrient homeostasis, cell wall integrity, and defense mechanisms [4]. This study demonstrated that roots dynamically adjust gene expression in response to heterogeneous soil conditions, with epidermal, exodermal, and cortical cells showing the most significant transcriptional changes.

The research employed sophisticated integration of scRNA-seq with spatial transcriptomics, validating computational predictions through Molecular Cartography—an optimized multiplexed fluorescence in situ hybridization technology [4]. This approach identified sequential expression patterns of genes involved in root hair differentiation, providing unprecedented insight into cellular specialization processes in natural growth environments.

Arabidopsis Life Cycle Atlas

The first single-cell spatial transcriptomic atlas spanning the complete Arabidopsis life cycle represents another significant achievement [13]. This comprehensive resource captures gene expression patterns of 400,000 cells across ten developmental stages, from seed to flowering maturity [13]. By pairing single-cell RNA sequencing with spatial transcriptomics, researchers maintained tissue context while profiling cellular diversity, enabling discovery of previously unknown genes involved in seedpod development.

This atlas provides a foundational resource for the plant science community, offering insights into the dynamic regulatory networks controlling plant development. The integrated web application makes this data accessible for hypothesis generation and comparative analysis, potentially accelerating discoveries in plant biotechnology and agriculture [13].

Future Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

Plant single-cell transcriptomics continues to evolve rapidly, with emerging technologies promising to overcome current limitations. Integration of multi-omics approaches at single-cell resolution—including epigenomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—will provide more comprehensive views of cellular function. Computational methods are also advancing, with new algorithms like scSGC offering improved clustering performance through soft graph constructions that better capture continuous cellular similarities [21].

As these technologies become more accessible and cost-effective, they will undoubtedly transform plant biology and agricultural biotechnology. The ability to profile cellular responses to environmental stresses, developmental cues, and genetic perturbations at single-cell resolution will accelerate breeding programs and engineering efforts aimed at developing more resilient and productive crops. By addressing the unique challenges posed by plant cell walls and cellular complexity, the methodologies outlined in this application note provide researchers with powerful tools to explore the intricate world of plant cellular diversity.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized plant biology by enabling the characterization of gene expression at an unprecedented resolution, moving beyond the limitations of traditional bulk transcriptomics that average signals across heterogeneous cell populations [22] [23]. This transformation is particularly significant for understanding complex plant systems composed of diverse, specialized cell types. The fundamental advantage of scRNA-seq lies in its ability to uncover cellular heterogeneity, identify rare cell types, reconstruct developmental trajectories, and reveal cell-type-specific responses to environmental stimuli [22] [24] [25]. While plant scRNA-seq applications initially lagged behind animal studies due to technical challenges posed by rigid cell walls, intensive methodological developments have now enabled robust profiling across major plant species, including the model organism Arabidopsis thaliana, staple crops like rice (Oryza sativa), and woody perennial species such as poplar (Populus spp.) [2] [25].

The core challenge in plant single-cell research involves overcoming the structural barrier of the cell wall to obtain high-quality single-cell suspensions without introducing significant transcriptional stress responses [23] [2]. Two primary approaches have emerged: protoplasting, which involves enzymatic removal of cell walls, and single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq), which isolates nuclei instead of whole cells [25] [2]. Each method presents distinct advantages and limitations that must be carefully considered in experimental design. This article provides a comprehensive overview of the major plant species studied using scRNA-seq, detailed experimental protocols, and emerging applications that collectively enhance our understanding of plant development, stress adaptation, and specialized metabolism.

Major Plant Species in Single-Cell Studies

1Arabidopsis thaliana: The Model Reference Organism

As the foremost model plant, Arabidopsis thaliana has served as the foundational system for developing and optimizing scRNA-seq protocols in plants. The species' extensively characterized genome, abundant genetic resources, and relatively simple organization have made it the primary reference for plant single-cell studies [13]. Research has predominantly focused on the root system, where scRNA-seq has revealed remarkable cellular heterogeneity and enabled the construction of detailed developmental trajectories [22] [2]. These investigations have successfully identified nearly all major expected cell types and uncovered previously undefined subclasses, providing unprecedented insights into the molecular regulation of root development and cell differentiation [24] [2].

Recent technological expansions have extended beyond roots to create comprehensive atlases spanning the entire Arabidopsis life cycle. A landmark 2025 study established the first genetic atlas to span the complete life cycle, capturing gene expression patterns of 400,000 cells across multiple developmental stages from single seed to mature plant [13]. This resource, created by integrating single-cell RNA sequencing with spatial transcriptomics, provides a foundational reference for the plant research community and enables deeper exploration of plant cell development across organs and timepoints [13]. The study demonstrated the dynamic and complex regulatory networks operating throughout plant development and identified numerous previously uncharacterized genes with cell-type-specific expression patterns [13].

Table 1: Key scRNA-seq Studies in Arabidopsis thaliana

| Tissue/Organ | Key Findings | Cell Numbers | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Root tip | Identification of cell types, developmental trajectories | Not specified | [22] |

| Entire life cycle | First comprehensive atlas across development | ~400,000 cells | [13] |

| Root | Characterization of brassinosteroid signaling mutants | Not specified | [22] |

| Shoot apex | Spatiotemporal gene expression atlas | Not specified | [22] |

2Oryza sativa(Rice): A Model Cereal Crop

As a staple food crop and model for monocot plants, rice has been the subject of pioneering scRNA-seq studies that bridge fundamental research with agricultural applications. Recent investigations have leveraged single-cell technologies to understand how rice roots adapt to realistic soil environments, moving beyond artificial laboratory conditions [4]. One notable 2025 study profiled over 79,000 high-quality cells from rice roots grown in both gel and soil conditions, revealing major expression changes in outer root cell types related to nutrient homeostasis, cell wall integrity, and defense mechanisms [4].

This research demonstrated that roots modify their gene expression profiles in soil conditions primarily in outer tissue layers (epidermis, exodermis, sclerenchyma, and cortex), while inner stele layers show relatively minor changes [4]. The integration of scRNA-seq with spatial transcriptomic approaches enabled the validation of cell-type-specific markers and provided insights into temporal gene expression dynamics during root hair differentiation [4]. Furthermore, the study explored how soil compaction stress triggers expression changes in cell wall remodeling and barrier formation programs, identifying abscisic acid signaling from phloem cells as a key regulator of this adaptive response [4].

Table 2: Key scRNA-seq Studies in Oryza sativa (Rice)

| Tissue/Organ | Key Findings | Cell Numbers | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Root (gel vs. soil) | Outer tissue adaptation to soil environment; nutrient homeostasis | >79,000 cells | [4] |

| Root | Response to soil compaction stress | >47,000 cells | [4] |

| Root | Integration with spatial transcriptomics | Not specified | [25] |

| Leaf and root | Stress responses under various conditions | Not specified | [25] |

3Populusspp. (Poplar): A Woody Perennial Model

Poplar species represent woody perennial plants that undergo secondary growth and produce wood, an economically and ecologically vital tissue. scRNA-seq applications in poplar have primarily focused on understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying vascular development and wood formation [26] [27]. An initial 2021 study established the transcriptional landscape of highly lignified poplar stems at single-cell resolution, identifying 20 putative cell clusters and reconstructing differentiation trajectories involved in phloem and xylem development [26]. The study optimized protoplast isolation protocols to overcome challenges posed by thick secondary cell walls and provided valuable insights into the heterogeneity of vascular cell types [26].

A groundbreaking 2025 study employed single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) to profile Populus stems, capturing 11,673 nuclei and identifying 26 clusters representing cell types in the cambium, xylem, phloem, and periderm [27]. This nuclei-based approach demonstrated significant advantages for capturing embedded cell types in lignified tissues compared to protoplast-based methods, revealing previously uncharacterized cell populations, including vessel-associated cells (VACs) [27]. Through gene regulatory network analysis and functional validation using CRISPR-Cas9 knockout lines, the study identified MYB48 as a key regulator of VAC function that influences vessel development, highlighting the potential for genetic modifications to enhance wood traits and stress resilience [27].

Table 3: Key scRNA-seq Studies in Populus spp.

| Tissue/Organ | Key Findings | Cell Numbers | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stem | Transcriptional landscape of lignified stems; 20 cell clusters | ~6,800 cells | [26] |

| Stem (snRNA-seq) | Identification of vessel-associated cells; 26 cell clusters | 11,673 nuclei | [27] |

| Differentiating xylem | Gene regulatory networks of wood formation | Not specified | [25] |

| Stem | Comparative analysis of protoplast vs. nuclei methods | Not specified | [27] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Sample Preparation: Protoplasts vs. Nuclei

The critical first step in plant scRNA-seq involves obtaining high-quality single-cell suspensions. Two primary approaches have been established across plant species, each with distinct advantages and limitations.

Protoplast Isolation involves enzymatic digestion of cell walls to release individual protoplasts. This method captures both nuclear and cytoplasmic RNAs, providing a more comprehensive view of the transcriptome [25]. However, protoplasting introduces significant cellular stress that alters gene expression patterns, and certain cell types (particularly those with thick secondary cell walls) may be underrepresented due to differential digestion efficiency [23] [2]. For Arabidopsis roots, a widely adopted protocol involves harvesting root tissues from 5-7 day old seedlings grown on vertical plates, followed by enzymatic digestion using cellulase and pectinase solutions for 1-2 hours at room temperature with gentle shaking [2]. The resulting protoplasts are filtered through mesh (30-40 μm), washed, and resuspended in appropriate buffer before counting and viability assessment [2].

For poplar stems, which present additional challenges due to extensive lignification, researchers have developed optimized protocols that may include mechanical disruption (e.g., scraping the bark off stem segments) prior to enzymatic digestion [26] [2]. The digestion time typically requires extension to 3-4 hours with specialized enzyme cocktails designed to break down woody tissues [26].

Nuclei Isolation offers an alternative approach that circumvents challenges associated with cell wall digestion. This method involves mechanical disruption of frozen or fresh tissue to release nuclei, which are then purified through density centrifugation or fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) [27] [25]. The nuclei approach particularly benefits studies of lignified tissues, field-grown samples, and time-course experiments where immediate processing is impractical [2]. A standard protocol for poplar stems involves flash-freeting stem internode segments in liquid nitrogen, grinding frozen tissue with a mortar and pestle, and homogenizing in nuclei isolation buffer containing non-ionic detergents [27]. The homogenate is filtered through mesh (20-40 μm), and nuclei are purified through density centrifugation or sorted using FACS before processing [27].

The choice between protoplasts and nuclei depends on research goals, plant species, and tissue type. Protoplasts are generally preferred when capturing the full transcriptome is essential, while nuclei offer advantages for difficult-to-digest tissues or when working with field samples [25].

Library Construction and Sequencing Platforms

Most plant scRNA-seq studies utilize droplet-based systems, with the 10x Genomics Chromium platform being the most widely adopted across species [25]. This platform enables high-throughput profiling of thousands of cells in a single experiment, with typical cell capture numbers ranging from 5,000 to 20,000 cells depending on tissue type and species [25]. The standard workflow involves encapsulating single cells (or nuclei) in droplets containing barcoded beads, reverse transcription, library preparation, and sequencing on Illumina platforms (HiSeq, NextSeq, or NovaSeq) [25].

For the 10x Genomics system, the Chromium Single Cell 3' Reagent Kits (v2, v3, or v3.1) are commonly used, targeting the 3' end of transcripts and incorporating cell barcodes and unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to distinguish individual molecules and cells [25]. Sequencing depth typically ranges from 20,000 to 50,000 reads per cell, depending on the complexity of the transcriptome and research objectives [25].

Alternative platforms include the BD Rhapsody system, which has been applied to rice inflorescence and leaf tissues, and plate-based methods like Smart-seq2 that provide full-length transcript coverage but with lower throughput [23] [25]. The selection of an appropriate platform involves balancing throughput, gene detection sensitivity, cost considerations, and compatibility with available sample preparation methods.

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for Plant Single-Cell RNA Sequencing

Bioinformatic Analysis and Data Interpretation

Following sequencing, raw data processing typically involves alignment to the respective reference genome (Arabidopsis TAIR10, rice MSU7, poplar JGI v4.1), barcode assignment, UMI counting, and gene expression quantification using pipelines like Cell Ranger (10x Genomics) or kallisto bustools [4] [27]. Downstream analysis utilizes specialized tools such as Seurat, Monocle, and Asc-Seurat for quality control, data integration, dimensionality reduction, clustering, and cell type annotation [27] [2].

Quality control metrics include removing cells with unusually high or low gene counts, excessive mitochondrial gene percentage (indicating stressed cells), and doublets (multiple cells incorrectly identified as one) [27]. For cross-species comparisons, integration methods like Harmony or Seurat's CCA anchor-based integration are employed to batch-correct datasets from different conditions or species [4].

Cell type annotation relies on marker gene identification and comparison with previously established signatures. Spatial validation techniques, such as Molecular Cartography or multiplexed FISH, have become increasingly important for confirming cell type identities and localization, particularly in species with limited prior characterization [4]. Developmental trajectories are reconstructed using pseudotime analysis tools (Monocle, PAGA, Slingshot) that order cells along differentiation pathways based on transcriptional similarities [22] [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Solutions for Plant scRNA-seq

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Wall Digesting Enzymes | Protoplast isolation by breaking down cellulose, pectin, and hemicellulose | Cellulase (1.5%), Pectinase (0.75%), Macerozyme in osmoticum solution |

| Osmoticum Solution | Maintain protoplast stability during and after digestion | Mannitol (0.4-0.6 M) or Sorbitol with calcium chloride |

| Nuclei Isolation Buffer | Stabilize nuclei during extraction and purification | Tris-HCl, MgCl2, Sucrose, NaCl, β-mercaptoethanol, non-ionic detergents |

| Density Gradient Media | Purify nuclei away from cellular debris | Percoll or iodixanol gradients (10%-40%) |

| 10x Genomics Chip | Partition single cells into nanoliter droplets | Chromium Single Cell A Chip, B Chip, or Chip K |

| Barcoded Beads | Capture mRNA and attach cell barcodes/UMIs | 10x Genomics Gel Beads with barcoded oligo-dT primers |

| Reverse Transcription Master Mix | Convert captured mRNA to cDNA | Template Switching Oligo, dNTPs, reverse transcriptase, additives |

| Library Construction Kit | Prepare sequencing libraries from cDNA | Chromium Single Cell 3' Library Kit with sample index primers |

| Viability Stain | Assess protoplast/nuclei integrity and quality | Fluorescein diacetate (FDA), Propidium Iodide (PI), or DAPI for nuclei |

Signaling Pathways and Regulatory Networks

Single-cell transcriptomics has revealed intricate regulatory networks and signaling pathways that operate in a cell-type-specific manner throughout plant development and environmental responses. In Arabidopsis roots, scRNA-seq has elucidated the brassinosteroid signaling pathway and its role in regulating cell division plane orientation and cellular anisotropy [22]. Pseudotime analysis of root single-cell data has reconstructed continuous differentiation trajectories, revealing finely resolved cascades of cell fate transitions and the transcriptional programs that drive them [22].

In poplar, scRNA-seq analyses have identified hierarchical regulatory networks controlling secondary cell wall biosynthesis in xylem cells, including master transcription factors such as SND1, NST1, VND1, MYB46, and MYB83 that coordinate the expression of biosynthetic genes for cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin [26] [27]. The 2025 snRNA-seq study further uncovered a vessel-associated cell (VAC)-specific regulatory network with MYB48 as its primary regulator, demonstrating how specialized cell types within vascular tissues contribute to wood formation and vessel development [27].

Environmental response pathways also exhibit striking cell-type specificity. Rice root studies revealed how abscisic acid (ABA) signaling, particularly from phloem cells, regulates cell wall remodeling and barrier formation in response to soil compaction stress [4]. Similarly, outer root cell types (epidermis, exodermis, sclerenchyma) show specialized expression of genes involved in nutrient homeostasis, defense responses, and cell wall integrity when adapting to soil versus gel environments [4].

Figure 2: Cell-Type-Specific Signaling Pathways in Plant Systems

Future Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

The application of scRNA-seq technologies to major plant species has fundamentally transformed our understanding of plant development, stress adaptation, and specialized metabolism. The ongoing development of more comprehensive single-cell atlases across species, tissues, and environmental conditions will provide increasingly powerful resources for the plant research community [13] [24]. Future directions include the integration of single-cell transcriptomics with other omics technologies (epigenomics, proteomics, metabolomics), spatial mapping approaches, and functional validation through genetic engineering [24] [25].

Technical advancements will likely focus on improving cell capture efficiency, especially for recalcitrant cell types, reducing costs to enable larger-scale studies, and developing computational methods specifically optimized for plant datasets [23] [25]. The creation of centralized, open-access databases for plant single-cell data will facilitate cross-study comparisons and meta-analyses, accelerating discoveries across species [24]. Additionally, the application of single-cell technologies to non-model plant species will expand our understanding of plant diversity and enable biotechnology applications in a broader range of crops and bioenergy species [24] [25].

As these technologies continue to mature, single-cell genomics promises to unlock unprecedented opportunities for plant synthetic biology, including the identification of cell-type-specific promoters for precision engineering, elucidation of regeneration mechanisms to overcome transformation bottlenecks, and the development of strategies for enhancing crop productivity, stress resilience, and sustainable biomass production [25]. The integration of single-cell data with explainable artificial intelligence approaches will further enhance our ability to predict and design optimal genetic modifications for targeted improvements in plant traits [25].

In conclusion, single-cell RNA sequencing has established itself as an indispensable tool for plant biology research, with robust protocols now available for major species including Arabidopsis, rice, and poplar. The continued refinement of these methodologies and their application to fundamental and applied research questions will undoubtedly yield transformative insights into plant development, function, and adaptation, ultimately supporting efforts to address global challenges in food security, renewable energy, and environmental sustainability.

Choosing and Implementing the Right Protocol: A Methodological Guide for Plant Tissues

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized plant biology by enabling transcriptomic profiling at an unprecedented cellular resolution. This transformative technology provides critical insights into cellular heterogeneity, lineage differentiation, and cell-type-specific gene expression patterns in complex plant tissues [28]. Unlike traditional bulk RNA-seq methods that average gene expression across thousands of cells, thereby masking unique cellular phenotypes, scRNA-seq reveals the distinct transcriptomic profiles of individual cells [29]. This capability is particularly valuable for identifying rare cell types, mapping cellular differentiation pathways, and understanding cell-specific responses to environmental stimuli in plants [28] [18].

The application of scRNA-seq in plant systems presents unique challenges not typically encountered in animal studies. Plant cells are encapsulated by rigid cell walls that hinder isolation of intact protoplasts, and certain tissues contain diverse cell types with varying sizes and biochemical properties [11]. Additionally, plant cells often have low RNA content and high levels of secondary metabolites that can interfere with library preparation [9]. These technical barriers have historically limited scRNA-seq applications in non-model plant organisms, creating a need for specialized approaches and protocols [28]. This application note provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of three prominent scRNA-seq platforms—10x Genomics Chromium, BD Rhapsody, and SPLiT-seq—within the specific context of plant tissue research, offering guidance on platform selection, optimized protocols, and practical implementation considerations for plant scientists.

The three platforms employ distinct technological approaches for single-cell capture and barcoding. 10x Genomics Chromium utilizes microfluidic droplet-based technology to partition individual cells into nanoliter-scale Gel Beads-in-emulsion (GEMs) where cell lysis and barcoding occur [29]. BD Rhapsody employs a microwell-based system where cells are randomly deposited into picoliter wells under gravity before mRNA capture by barcoded magnetic beads [30] [9]. SPLiT-seq represents a fundamentally different approach that uses combinatorial barcoding of fixed cells or nuclei in suspension without requiring physical partitioning into compartments [9].

Table 1: Technical Specifications of scRNA-seq Platforms for Plant Research

| Parameter | 10x Genomics Chromium | BD Rhapsody | SPLiT-seq |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technology Principle | Microfluidic droplet-based | Microwell-based | Combinatorial barcoding in suspension |

| Cell Throughput | 80K to 960K cells per kit (Chromium X) [29] | Thousands to tens of thousands [31] | Hundreds of thousands in single experiment [9] |

| Cell Capture Efficiency | Up to 80% recovery efficiency [29] | ~30% effective capture rate (excluding multiplets) [30] | Not applicable (no physical partitioning) |

| Barcoding Strategy | Gel Bead with barcoded oligo-dT primers [29] | Magnetic beads with barcoded primers [31] | Sequential ligation of barcodes in plates [9] |

| Compatibility with Plant Cells | Standard protocols require optimization; Flex option for fixed samples [29] | Validated for cells <20μm [9]; suitable for smaller plant cells | Compatible with fixed nuclei; ideal for difficult-to-dissociate tissues [9] |

| Library Type | 3' or 5' gene expression with UMIs [29] | Whole Transcriptome Analysis (WTA), targeted panels, protein expression [32] | Whole transcriptome with UMIs [9] |

| Instrument Requirement | Chromium X Series instrument [29] | BD Rhapsody Scanner or Express System [32] | No specialized instruments; standard laboratory equipment [9] |

| Cost Considerations | Higher reagent and instrument costs | Moderate to high | Lower cost; minimal reagent requirements [9] |

Table 2: Performance Characteristics in Plant Tissue Applications

| Characteristic | 10x Genomics Chromium | BD Rhapsody | SPLiT-seq |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity (Gene Detection) | High sensitivity with GEM-X technology [29] | Enhanced detection of low-mRNA content cells [30] | Lower sensitivity due to fixed material |

| Cell Size Limitations | Adaptable to various sizes via protocol optimization | Limited to cells <20μm unless using nuclei [9] | No size restrictions with nuclei |

| Sample Multiplexing | Limited without additional kits | Extensive multiplexing with sample tags [30] [31] | Built-in multiplexing capability [9] |

| Data Quality from Complex Plant Tissues | High-quality data with proper tissue dissociation | Better representation of low-RNA cell types [30] | Variable quality; depends on fixation |

| Handling of Difficult Samples | Flex option enables FFPE and fixed samples [29] | Suitable for delicate cells; reduced stress during capture [31] | Ideal for archived, frozen, or problematic samples [9] |

| Protocol Duration | Standard workflow: 1-2 days | ~2 days including sample tagging | Extended due to multiple batching steps |

The technological differences between these platforms lead to practical implications for plant research. Droplet-based systems like 10x Genomics offer high throughput and standardized workflows but may underrepresent cell types with low mRNA content, which could include certain plant cell types [30]. Microwell-based approaches like BD Rhapsody demonstrate enhanced capture of cells with low RNA content, potentially providing better representation of the full cellular diversity in plant tissues [30]. SPLiT-seq's unique strength lies in its compatibility with fixed cells and nuclei, which is particularly advantageous for plant samples that require prolonged processing or present challenges for live cell isolation [9].

Experimental Protocols for Plant Tissues

Sample Preparation and Cell Isolation

Successful scRNA-seq of plant tissues begins with optimal sample preparation to generate high-quality single-cell suspensions while preserving RNA integrity. The fundamental challenge in plant sample preparation lies in overcoming the rigid cell wall without inducing stress responses that alter transcriptional profiles.

Protoplast Isolation: For species with tractable cell walls, protoplast isolation can be achieved through enzymatic digestion using combinations of cellulases, pectinases, and hemicellulases [11]. The RevGel-seq method has emerged as a breakthrough approach that streamlines protoplast isolation and resolves many challenges associated with traditional methods [11]. Critical factors during protoplast preparation include optimizing enzyme treatment duration, temperature, and osmotic potential to maximize yield and viability while minimizing stress responses [11].

Nuclei Isolation: For plant tissues with rigid cell walls or high secondary metabolite content, single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) bypasses the need for protoplast isolation [9]. Nuclei isolation involves tissue homogenization in specific buffers that maintain nuclear integrity while preventing clumping. snRNA-seq offers several advantages for plant research: it eliminates the need for protoplasts, avoids potential stress responses triggered by cell isolation methods, and enables work with frozen or preserved specimens [9]. However, it should be noted that snRNA-seq captures fewer transcripts and may include more immature RNA molecules than scRNA-seq [9].

Quality Control: Regardless of isolation method, cell quality control is essential. Viability should exceed 80% as assessed by fluorescent staining (e.g., acridine orange/propidium iodide), and samples should be filtered to remove aggregates and debris [33] [31]. The buffer composition is critical—for many plant cells, maintaining osmotic balance with appropriate mannitol or sucrose concentrations preserves membrane integrity during processing [11].

Platform-Specific Protocol Adaptations

Each platform requires specific protocol adaptations for optimal performance with plant samples.

10x Genomics Chromium Protocol:

- Sample Input: Prepare single-cell suspension at 500-1,200 cells/μL in PBS with 0.04% BSA [33]. For plant protoplasts, adjust buffer to maintain osmotic balance.

- GEM Generation: Combine cells, barcoded Gel Beads, and partitioning oil on a Chromium microfluidic chip. The redesigned GEM-X chips generate twice as many GEMs at smaller volumes, reducing multiplet rates [29].

- Barcoding and Reverse Transcription: Within each GEM, cells are lysed, and mRNA is reverse transcribed with cell-specific barcodes [29].

- Library Preparation: cDNA is amplified and enzymatically fragmented before adding sample indexes and sequencing adapters [29].

- Plant-Specific Modifications: For the Flex platform, fixation conditions must be optimized for plant tissues to ensure adequate probe penetration while preserving RNA quality [29].

BD Rhapsody Protocol:

- Sample Tagging (Optional): Incubate cells with antibody-based sample tags for multiplexing [31]. For plant cells, validate antibody compatibility or use alternative tagging approaches.

- Cell Loading: Load single-cell suspension into BD Rhapsody Cartridge for gravitational settling into microwells [32].

- mRNA Capture: Add magnetic beads containing barcoded primers to capture mRNA from individual cells [31].

- Library Preparation: Perform reverse transcription on beads, followed by cDNA amplification and library preparation for whole transcriptome or targeted analysis [32].

- Plant Adaptation: Pre-filter plant protoplasts to remove debris that could clog microwells. For larger plant cells, optimize loading density to minimize multiplets [9].

SPLiT-seq Protocol:

- Cell Fixation: Fix cells or nuclei with formaldehyde to preserve RNA while permitting enzymatic reactions [9].

- Combinatorial Barcoding: Distribute fixed cells across multiple wells for sequential barcode ligation steps [9].

- Pooling and Splitting: Between barcoding rounds, pool and redistribute cells to achieve combinatorial cell-specific barcodes [9].

- Library Preparation: After final barcoding, reverse transcribe and prepare libraries from the fully barcoded material [9].