Advancing Robust Plant Science: A Comprehensive Guide to Enhancing Experimental Reproducibility

This article provides a comprehensive framework for improving reproducibility in plant science, addressing a critical need for robust and transparent research.

Advancing Robust Plant Science: A Comprehensive Guide to Enhancing Experimental Reproducibility

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for improving reproducibility in plant science, addressing a critical need for robust and transparent research. It begins by establishing foundational concepts—defining key terms like repeatability, replicability, and reproducibility—and explores the systemic pressures that challenge reliable science. The guide then transitions to practical application, detailing standardized protocols for plant-microbiome studies, fluorescence microscopy, and phytohormone profiling using LC-MS/MS. It further offers troubleshooting strategies to overcome common pitfalls, such as managing environmental variability and avoiding statistical biases like p-hacking. Finally, the article covers validation through multi-laboratory ring trials and computational replicability, synthesizing key takeaways to empower researchers in generating reliable, impactful data that accelerates discovery in plant biology and its applications.

Defining the Crisis and Core Concepts: Why Reproducibility is Fundamental to Plant Science

Reproducibility is a fundamental pillar of the scientific method, yet it represents a significant hurdle in modern plant science. A landmark survey revealed that more than 70% of researchers had failed to reproduce another scientist's experiments, and more than 50% were unable to reproduce their own [1]. In plant research, this challenge is intensified by the inherent complexity of biological systems and their interactions with dynamic environments [2]. This technical support center is designed to provide plant scientists with practical, evidence-based troubleshooting guides and resources to navigate these challenges, enhance the robustness of their work, and advance the field of reproducible plant science.

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: Our team is new to robust research practices. What is the most effective way to start implementing them?

Adopting new practices can be overwhelming. A phased, strategic approach is recommended [3].

- Rule 1: Make a Shortlist. Do not attempt to implement every robust practice at once. Create a shortlist of one to three practices that are most relevant to your current project stage and within your team's current capacity. Focus on practices that address known weaknesses in your workflow or that are required by funders or target journals [3].

- Rule 2: Join a Community. Seek out both a micro-community (allies within your direct research environment) and a macro-community (broader networks like ReproducibiliTea or international Reproducibility Networks). These communities provide critical support, training, and a platform to share experiences [3].

- Rule 3: Talk to Your Research Team. Schedule a meeting with your supervisor and collaborators to discuss your shortlist. Prepare a brief presentation explaining what you've learned, the practices you propose, and the evidence for their benefits. Approach the conversation with a positive attitude, focusing on future improvements rather than criticizing past work [3].

Q2: What are the most common technical sources of variability in plant-microbiome studies, and how can we control for them?

Technical variability is a major barrier to replicability in plant-microbiome research. Key sources and their solutions are summarized in the table below [4] [5] [6].

Table: Troubleshooting Technical Variability in Plant-Microbiome Studies

| Source of Variability | Impact on Reproducibility | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Protocols | Different kits and washing procedures can differentially lyse taxa, biasing diversity and functional estimates [4]. | Standardize the DNA extraction kit across all project labs. Implement repeated washing steps to improve retrieval of rare taxa [4]. |

| Sequencing & Bioinformatics | Choice of platform (short vs. long-read), primers, reference databases, and classifiers can lead to different taxonomic and functional profiles [4]. | Use a standardized bioinformatics pipeline. Pair high-quality databases (e.g., SILVA) with consistent classifier software and versions. Report all parameters transparently [4]. |

| Plant Growth Conditions | Differences in light quality (LED vs. fluorescent), intensity, temperature, and photoperiod between growth chambers can alter plant physiology and microbiome assembly [6]. | Use data loggers to monitor and report environmental conditions. Where possible, standardize growth chamber specs or use fabricated ecosystems (EcoFABs) for highly controlled experiments [6]. |

| Inoculum Preparation | Varying methods for preparing synthetic communities (SynComs) can lead to different starting cell densities and community compositions [5] [6]. | Use optically dense to colony-forming unit (OD600 to CFU) conversions to ensure equal cell numbers. Source strains from a public biobank and use shared cryopreservation protocols [6]. |

Q3: How can we improve the reproducibility of field experiments, where environmental factors are inherently variable?

For field research, reproducibility means obtaining comparable results through independent studies in different environments, which requires exceptional documentation [2].

- Implement Detailed Metadata Standards: Use established vocabularies and data architectures, such as those from the International Consortium for Agricultural Systems Applications (ICASA), to document initial field conditions (Ft=0), crop genetics (G), environment (Et), and management (Mt) [2].

- Publish Detailed Protocols: Make protocols for measuring plant phenotypes (Pt) publicly available on platforms like

protocols.io. This should include details on plot area, instrument configurations, sampling procedures, and data processing steps [2]. - Avoid Questionable Research Practices: Actively guard against p-hacking, HARKing (Hypothesizing After the Results are Known), and publication bias, which increase the risk of false positives that cannot be reproduced [2].

Q4: We face resistance from collaborators who view new reproducible practices as too time-consuming. How can we address this?

Resistance is a common social and technical challenge [3].

- Rule 4: Address Resistance Constructively. Listen to the concerns of your colleagues. Acknowledge the required effort and focus on the long-term benefits, such as stronger papers, more credible findings, and easier compliance with evolving funder and journal policies [3].

- Rule 6: Compromise and Be Patient. Be willing to start small. If sharing all data and code is too large a first step, propose starting with better version control for analysis code or using a standardized lab protocol. View this as a long-term cultural shift, not a one-time change [3].

- Rule 9: Get Credit. Emphasize that reproducible practices are increasingly recognized. Making data and code publicly available can lead to new citations and collaborations, making contributions more visible [3].

Experimental Protocols for Reproducible Science

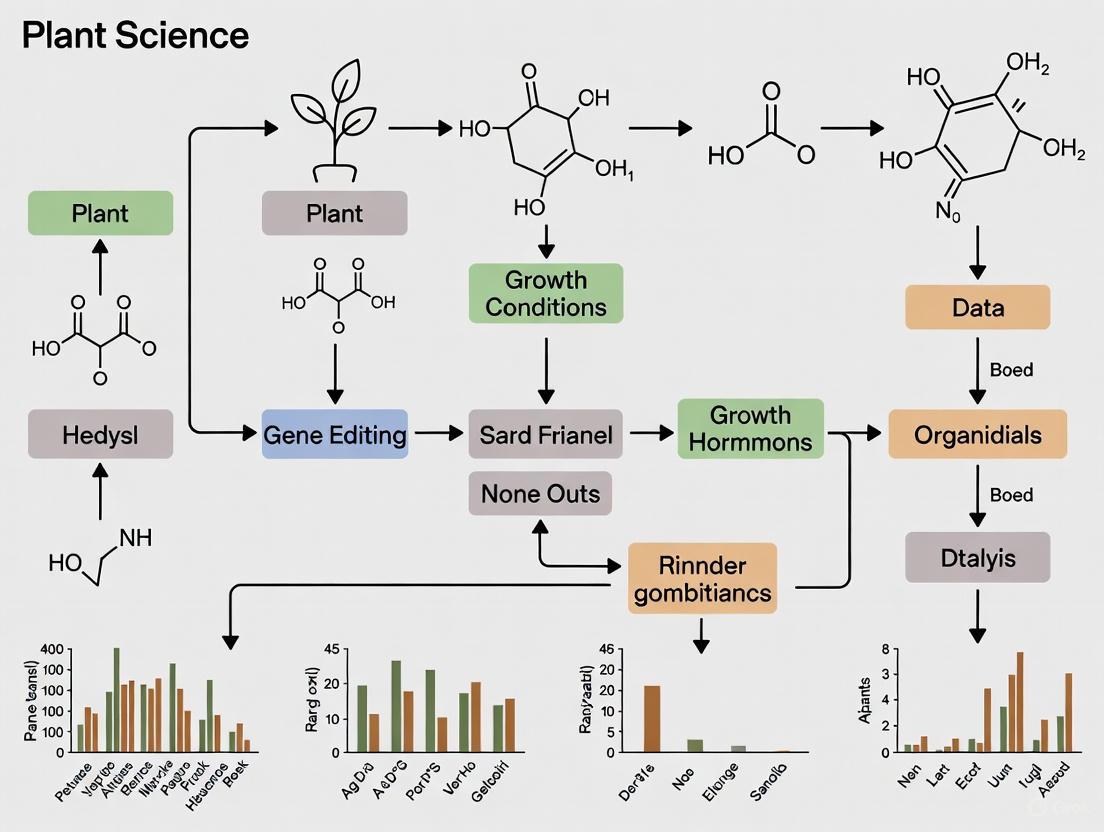

The following workflow diagram and protocol detail a successful multi-laboratory reproducibility study in plant-microbiome research, providing a template for robust experimental design.

Detailed Protocol: Multi-Laboratory Ring Trial for Plant-Microbiome Studies [5] [6]

This protocol ensures replicability across different laboratories by standardizing materials, methods, and data collection.

Material Distribution: The organizing laboratory ships all critical, non-perishable supplies to participating labs, including:

- EcoFAB 2.0 devices.

- Seeds of the model plant (Brachypodium distachyon).

- Aliquots of the Synthetic Community (SynCom) inoculum, frozen.

- Growth chamber data loggers.

- Detailed written protocols with annotated videos.

Plant Establishment:

- Seed Preparation: Dehusk seeds, surface sterilize, and stratify at 4°C for 3 days.

- Germination: Germinate seeds on standardized agar plates for 3 days.

- Transfer: Aseptically transfer seedlings to the EcoFAB 2.0 device for an initial 4 days of growth.

Inoculation and Growth:

- Sterility Check: Test the sterility of the EcoFAB devices by plating spent medium on LB agar.

- Inoculation: Inoculate 10-day-old seedlings with the SynCom resuspended to a precise density (e.g., 1 × 10⁵ bacterial cells per plant).

- Growth: Grow plants for a set period (e.g., 22 days after inoculation), with regular water refills and maintenance.

Data and Sample Collection: All labs follow identical templates.

- Plant Phenotyping: Measure shoot fresh and dry weight. Perform root scans for image analysis.

- Sample Collection: Collect root and media samples for 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing. Collect filtered media for metabolomic analysis by LC-MS/MS.

Centralized Analysis: All samples are shipped to a single organizing laboratory for sequencing and metabolomic analysis to minimize analytical variation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Standardized reagents and tools are the foundation of reproducible research. The following table lists key materials used in a benchmark reproducibility study.

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Reproducible Plant-Microbiome Studies [5] [6]

| Item | Function / Rationale | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|

| EcoFAB 2.0 Device | A sterile, fabricated ecosystem that provides a highly controlled and reproducible habitat for studying plant-microbe interactions in a laboratory setting. | Provided by the organizing laboratory [6]. |

| Standardized SynCom | A synthetic microbial community of known composition that limits complexity while retaining functional diversity, enabling mechanistic studies. | 17-member community available from public biobank (DSMZ) [6]. |

| Model Plant | A well-characterized plant species with established growth protocols and genetic tools, minimizing host-introduced variability. | Brachypodium distachyon (e.g., specific ecotype or line) [6]. |

| Standardized Growth Medium | A defined, sterile nutrient solution that supports plant and microbial growth, ensuring all labs use an identical nutritional base. | Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium or other specified formulation [6]. |

| Data Loggers | Devices to continuously monitor and record environmental conditions (e.g., temperature, light) within growth chambers, documenting critical variables. | Shipped with initial supply package [6]. |

| Public Biobank | A centralized repository for microbial strains that guarantees long-term access and genetic stability of research materials for the global community. | Leibniz-Institute DSMZ-German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures [6]. |

FAQs: Understanding the Core Concepts

What is the fundamental difference between repeatability, replicability, and reproducibility?

The core difference lies in who is conducting the follow-up work and under what conditions. These terms form a hierarchy of evidence, with each level providing stronger confirmation of a finding's robustness [2] [7].

The table below summarizes the key distinctions.

| Concept | Key Question | Who & How | Primary Goal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Repeatability [8] [7] | Can my own team get the same result again? | The same team repeats the experiment under the exact same conditions (same location, equipment, methods). | Verify that the initial result was not a random artifact or error. |

| Replicability [2] [9] | Can my team get the same result in a new context? | The same team repeats the experiment under different but related conditions (e.g., different season, location, sample). | Assess the stability and generalizability of the result within a research group. |

| Reproducibility [2] [9] | Can an independent team confirm our finding? | A different, independent team attempts to obtain consistent results, often using their own data and methods. | Provide independent confirmation, which is the highest standard for accepting a scientific finding. |

Why is there so much confusion around these terms?

Disciplines like computer science, biomedicine, and agricultural research have historically used these terms in different, and sometimes contradictory, ways [10]. For instance, what agricultural researchers define as "reproducibility" (independent confirmation) is labeled as "replicability" in the 2019 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) report [2] [10]. This guide uses the definitions common in agricultural and biological research [2].

What is the "reproducibility crisis"?

The "reproducibility crisis" refers to widespread concerns across many scientific fields that a surprising number of published research findings are difficult or impossible to reproduce or replicate [10] [7]. A landmark 2015 study, for example, found that only 68 out of 100 reproduced psychology experiments provided statistically significant results that matched the original findings [7].

Troubleshooting Guide: Improving Robustness in Your Research

My results are not repeatable. What should I check?

If you cannot get consistent results within your own lab, the issue often lies in uncontrolled variables or methodological instability.

- Problem: Inconsistent experimental protocols.

- Problem: Unaccounted variability in biological materials or reagents.

- Solution: Source materials from reputable repositories where possible. For plant science, use standardized model systems. In a recent multi-laboratory plant-microbiome study, all labs used the same model grass (Brachypodium distachyon) and synthetic bacterial communities sourced from a public biobank (DSMZ) to ensure consistency [6] [5].

- Problem: Uncontrolled environmental conditions.

- Solution: Implement strict control over growth chamber conditions (light, temperature, humidity) and use data loggers to continuously monitor them. Even with standardized devices (EcoFAB 2.0), differences in light quality (fluorescent vs. LED) and temperature were noted as sources of inter-laboratory variability [6].

- Problem: Improper statistical analysis or "p-hacking".

My study was repeatable, but another lab could not replicate it. What are the common causes?

When a result holds in your lab but not in others, the issue often involves findings that are highly sensitive to specific, undocumented local conditions.

- Problem: Inadequate documentation of initial conditions and management.

- Solution: Comprehensively document all aspects of your experimental setup. The ICASA data standards provide a useful vocabulary for describing crop genetics (G), the initial field state (Ft=0), environment (Et), and management (Mt) [2]. Share this metadata alongside your results.

- Problem: The finding is genuinely context-dependent.

- Solution: Design studies with multiple locations and seasons from the outset. This helps quantify how results vary across environments and identifies the boundary conditions for your findings [2].

- Problem: The original method description lacks crucial details.

- Solution: Beyond the basic method, document instrument calibrations, sampling criteria, software versions, and code. The

Prometheusplatform andprotocols.iohost detailed protocols for plant physiology and other fields [2].

- Solution: Beyond the basic method, document instrument calibrations, sampling criteria, software versions, and code. The

How can I design my research to be reproducible from the start?

Proactively designing for reproducibility is more effective than trying to achieve it after the fact.

- Strategy: Adopt the "FAIR" Guiding Principles.

- Solution: Ensure your data and code are Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable [11]. Deposit data in public repositories, use clear licenses, and structure data in standard, well-documented formats.

- Strategy: Use version control and automation.

- Strategy: Share research artifacts comprehensively.

The following table lists essential tools and resources that support reproducible research practices.

| Tool / Resource | Function | Example / Context |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic Lab Notebooks (ELNs) [11] | Digital, searchable, and shareable record-keeping for experiments and observations. | Overcomes limitations of paper notebooks; easy to back up and share with collaborators. |

| Protocol Repositories [2] [11] | Platforms for sharing detailed, citable, and version-controlled methods. | The plant-microbiome ring trial used protocols.io to host its detailed, video-annotated protocol [6] [5]. |

| Model Organism Repositories [5] [11] | Repositories that maintain and distribute standardized biological materials. | The Leibniz-Institute DSMZ (German Collection of Microorganisms) provided the synthetic bacterial community for the reproducible plant-microbiome study [6]. |

| Workflow Management Tools [8] | Tools that automate and create reproducible data analysis pipelines. | Nextflow, Snakemake, and Data Version Control (DVC) help ensure computational analyses are repeatable. |

| Data Version Control (DVC) [8] | A version control system for data, model files, and experiments, integrated with Git. | Manages versions of large data files and models, maintaining lineage and enabling "time travel" for projects. |

| Open Science Framework (OSF) [12] | A free, open-source platform for collaboration and project management across the research lifecycle. | Helps researchers design studies, manage data, code, and protocols, and share them publicly or privately. |

Visual Guide: The Confirmation Pathway in Science

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between repeatability, replicability, and reproducibility, and how they build towards a robust scientific finding.

Visual Guide: Workflow for a Reproducible Plant Experiment

This diagram outlines a generalized experimental workflow, based on a multi-laboratory study, that enhances reproducibility.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the "reproducibility crisis" in science? A significant portion of published scientific research is difficult or impossible for other researchers to reproduce or replicate. A 2016 survey found that over 70% of researchers have failed to reproduce another scientist's experiments, and more than 50% have failed to reproduce their own [13]. This lack of reproducibility undermines scientific progress and trust in published findings.

FAQ 2: How does the "publish or perish" culture directly harm research robustness? The "publish or perish" culture, where career advancement is tied to the quantity of publications in high-impact journals, creates a system that incentivizes speed and novelty over rigor. This pressure can lead to corner-cutting, such as inadequate sample sizes, flexible data analysis (p-hacking), and selective reporting of positive results, all of which erode the reliability of findings [14] [2]. Over 62% of biomedical researchers identify this culture as a primary driver of irreproducibility [13].

FAQ 3: Are there specific financial pressures that exacerbate this problem? Yes, two major financial pressures are:

- Intense competition for scarce funding: With less than one in five grants funded in some fields, researchers feel pressure to produce exciting, novel results to stand out, sometimes at the expense of thorough, confirmatory work [14].

- Funding biases against replication studies: Funding agencies often prioritize "novel" or "innovative" research, leaving little to no support for the crucial work of independently verifying previously published results [2].

FAQ 4: What are the human costs of these systemic pressures? These pressures contribute to chronic stress and burnout among researchers. A 2025 report indicates that over 80% of employees are at risk of burnout [15]. For research scholars specifically, major stressors include academic pressure, financial instability, and future uncertainty, which can detrimentally affect mental health and overall productivity [16].

FAQ 5: What practical steps can I take to improve the reproducibility of my plant science experiments? You can adopt several concrete practices:

- Use Standardized Protocols: Utilize detailed, community-vetted protocols from repositories like

protocols.ioorbio-protocol[17]. - Adopt Standardized Systems: Employ fabricated ecosystems (EcoFABs) and synthetic microbial communities (SynComs) where available to reduce variability [5] [6].

- Document Everything Meticulously: Use established data standards (like ICASA standards) to describe all environmental conditions, management practices, and genetic materials in detail [2].

- Pre-register Studies: Submit your hypothesis and analysis plan to a registry before conducting the experiment to reduce bias.

- Use Standardized Protocols: Utilize detailed, community-vetted protocols from repositories like

FAQ 6: Where can I find reproducible protocols and share my own? Several resources are available:

protocols.io: A platform for sharing and updating detailed protocols with version control [17].bio-protocol: A peer-reviewed journal publishing detailed life science protocols [17].- Community Networks: Platforms like Plantae host community-driven method and protocol networks where researchers can share, discuss, and troubleshoot protocols [17].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Results Across Replicates or Laboratories

This is a common issue in complex plant science experiments, often stemming from undocumented variations in methods, biological materials, or environmental conditions.

Step 1: Verify Protocol Uniformity

- Action: Ensure every lab or team member is using the exact same version of the protocol. Small deviations in buffer pH, incubation times, or seedling age can have large effects.

- Tip: Use a centralized, version-controlled protocol on a platform like

protocols.ioto ensure everyone accesses the same instructions [17].

Step 2: Standardize Biological and Material Resources

- Action: Source all key materials from the same supplier. For plant-microbiome studies, this includes using the same seed stock, synthetic microbial community (SynCom), and sterile growth devices (EcoFABs) [5] [6].

- Tip: If a key bacterial strain (e.g., Paraburkholderia sp. OAS925) is dominant, test its effect by running parallel experiments with and without it to understand its impact on community assembly [6].

Step 3: Audit Environmental Conditions

Step 4: Centralize Sample Analysis

Problem: My experiments are difficult to reproduce in my own lab over time.

This often points to issues with documentation or uncontrolled variables within your own experimental workflow.

Step 1: Enhance Visual Documentation

- Action: Supplement written protocols with photos and videos of critical steps, such as the physical appearance of a pellet, the exact method for collecting root material, or the setup of apparatus. This captures nuances that text cannot convey [17].

Step 2: Improve Metadata Collection

- Action: Systematically record all initial conditions (e.g., soil properties

F_t=0), environmental data (E_t), and management practices (M_t) for every experiment, as defined in the ICASA standards [2]. - Tip: A useful metric is to document your workflow so well that another researcher could reproduce your experiment ten years from now [2].

- Action: Systematically record all initial conditions (e.g., soil properties

Step 3: Check Reagent and Strain Integrity

- Action: Regularly validate your key reagents, antibodies, and microbial strains. Contamination, degradation, or genetic drift can silently invalidate results.

Quantifying the Problem: Data on Systemic Pressures

The tables below summarize key quantitative evidence of the systemic pressures facing researchers.

Table 1: The Reproducibility Crisis in Numbers

| Metric | Statistic | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Researchers unable to reproduce others' work | 70% | [13] |

| Researchers unable to reproduce their own work | 50% | [13] |

| Researchers who agree there is a significant reproducibility crisis | 52% | [13] |

| Biomedical researchers blaming "publish or perish" | 62% | [13] |

Table 2: The Impact of Workplace Stress on Researchers (2025 Data)

| Metric | Statistic | Source |

|---|---|---|

| U.S. workers experiencing daily work stress | ~50% | [15] |

| Workers at risk of burnout | >80% | [15] |

| Employee turnover attributable to workplace stress | 40% | [15] |

| Estimated annual cost to the U.S. economy from burnout | $300 billion | [15] |

Experimental Protocols for Enhancing Reproducibility

Detailed Methodology: A Multi-Laboratory Reproducibility Study in Plant-Microbiome Research

This protocol is adapted from a 2025 ring trial that successfully achieved reproducible results across five independent laboratories [5] [6].

1. Objective To test the reproducibility of synthetic community (SynCom) assembly, plant phenotype, and root exudate composition using standardized fabricated ecosystems (EcoFAB 2.0) and the model grass Brachypodium distachyon.

2. Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| EcoFAB 2.0 Device | A sterile, fabricated ecosystem that provides a controlled and consistent physical environment for plant growth, minimizing abiotic variability [5]. |

| Synthetic Microbial Community (SynCom) | A defined mixture of 17 bacterial strains isolated from a grass rhizosphere. Using a standardized community from a public biobank (e.g., DSMZ) ensures all labs use identical biological starting material [6]. |

| Brachypodium distachyon | A model grass organism with consistent genetic background and growth characteristics, reducing host-induced variability [5]. |

| protocols.io (DOI: 10.17504/protocols.io.kxygxyydkl8j/v1) | Hosts the detailed, step-by-step protocol with embedded annotated videos, ensuring all laboratories perform the experiment identically [6]. |

3. Step-by-Step Workflow

- Device Assembly: Assemble sterile EcoFAB 2.0 devices according to the provided protocol.

- Seed Preparation: Dehusk B. distachyon seeds, surface sterilize, and stratify at 4°C for 3 days. Germinate on agar plates for 3 days.

- Transfer & Growth: Transfer seedlings to the EcoFAB 2.0 device and grow for an additional 4 days.

- Inoculation: Conduct a sterility test. Inoculate 10-day-old seedlings with the SynCom (e.g., the full 17-member community or a 16-member community lacking a key strain like Paraburkholderia sp. OAS925). The final inoculum should be standardized to 1 × 10^5 bacterial cells per plant.

- Monitoring & Harvest: Refill water as needed and perform root imaging at designated timepoints. Harvest plants at 22 days after inoculation (DAI).

- Data Collection: Measure plant biomass (shoot fresh/dry weight), perform root scans, and collect samples for 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing and metabolomic analysis (LC-MS/MS). Use standardized data collection templates.

- Centralized Analysis: Send all samples for sequencing and metabolomic analysis to a single organizing laboratory to minimize analytical variation [6].

4. Critical Troubleshooting Points

- Sterility Failures: Less than 1% of tests should show microbial colony growth. Check for cracked plate lids and proper sterile technique [6].

- Inter-lab Variability: Differences in plant biomass between labs are expected due to growth chamber differences (light quality, temperature). Use data loggers to record and account for this variation [6].

- Community Assembly Dominance: If one bacterial strain (e.g., Paraburkholderia) dominates the final microbiome, this is an expected biological result. Compare results with and without the dominant strain to understand its role [6].

Visualizing the Systemic Pressures and Their Impact

The diagram below maps the logical relationships between the root causes of systemic pressures, their direct consequences on research practices, and the ultimate outcome for scientific robustness.

Technical Support Center: Reproducibility in Plant Science

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the difference between repeatability, replicability, and reproducibility? In agricultural and plant science research, these terms have specific meanings [2]:

- Repeatability: The ability of a single research group to obtain consistent results when an analysis or experiment is repeated under the same conditions (same methods, equipment, and location).

- Replicability: The ability of a single research group to obtain consistent results from a previous study when using the same methods, but across different environments, seasons, or locations.

- Reproducibility: The ability of an independent research team to obtain comparable results from a study directed at the same research question, often under different conditions (e.g., different cultivars, locations, or management practices).

Why is there a "reproducibility crisis" in preclinical and biological research? Concerns about a crisis stem from high-profile reports of irreproducible results. A survey of Nature readers identified key contributing factors [18]:

- Selective reporting

- Pressure to publish

- Low statistical power or poor analysis

- Insufficient replication within the original laboratory

- Poor experimental design

- Methods or code not being available

How can a framework of uncertainty help instead of just chasing reproducibility? Systematically assessing uncertainty, rather than viewing studies as simply reproducible or not, is a more productive approach [19]. This involves identifying all potential sources of uncertainty in a study—from initial assumptions and measurements to models and data analysis. This helps explain why results from different labs may vary and provides a clearer path for building confidence in scientific claims.

What are the most critical factors for achieving inter-laboratory reproducibility in plant-microbiome studies? A recent multi-laboratory ring trial demonstrated that standardized protocols and materials are crucial. Key factors for success include [5] [6]:

- Using identical, centrally sourced materials (seeds, synthetic microbial communities, growth devices).

- Following detailed, step-by-step protocols with annotated videos.

- Centralizing complex analytical procedures like sequencing and metabolomics.

- Comprehensive documentation of all experimental parameters.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Inconsistent plant phenotypes across replicate experiments.

- Potential Cause: Uncontrolled variation in growth chamber conditions (light quality, intensity, temperature).

- Solution:

- Use data loggers to continuously monitor and record environmental conditions in growth chambers [6].

- Standardize the type of growth lights (e.g., LED) across experiments where possible.

- Source all seeds from a single, standardized batch.

Problem: Bacterial community composition in synthetic communities (SynComs) shifts unpredictably.

- Potential Cause: The presence of a highly competitive, dominant bacterial strain that outcompetes others.

- Solution:

- Characterize the colonization dynamics of all strains in your SynCom individually and in combination.

- As demonstrated in a recent study, adjusting the initial inoculum ratios or removing a dominant strain like Paraburkholderia sp. can lead to more stable and diverse community structures [5] [6].

- Control environmental factors like pH, which can influence the competitive ability of certain strains [5].

Problem: Contamination is detected in sterile plant growth systems.

- Potential Cause: Breaches in sterile technique or integrity of the growth device.

- Solution:

- Implement mandatory sterility checks at multiple time points during the experiment. This can be done by plating spent growth medium on nutrient-rich agar [6].

- Visually inspect growth devices for cracks or leaks before use.

- Provide detailed protocols for surface sterilization of seeds and device assembly.

Problem: Inconsistent or conflicting results between similar studies.

- Potential Cause: Failure to adequately document and report critical experimental variables (e.g., exact patient treatment, age, how a sample was thawed) [19].

- Solution:

- Adopt "minimum information" standards from your field (e.g., MIATA for T-cell assays) to ensure all critical variables are reported [19].

- Use structured data formats, such as the ICASA standards, to document experiments, including initial conditions (Ft=0), genetics (G), environment (Et), and management (Mt) [2].

- Systematically map all potential sources of uncertainty in your study using cause-and-effect diagrams [19].

Table 1: Key Findings from a Five-Laboratory Reproducibility Study in Plant-Microbiome Research [6]

| Parameter Measured | Axenic Control | SynCom16 Inoculation | SynCom17 Inoculation | Observation Across Labs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shoot Biomass | Baseline | Significant decrease | Significant decrease | Consistent across all 5 laboratories |

| Root Development (after 14 DAI) | Baseline | Moderate decrease | Consistent decrease | Observed from 14 days after inoculation onwards |

| Microbiome Composition (Root) | N/A | Highly variable | Dominated by Paraburkholderia (98%) | Highly consistent effect of Paraburkholderia |

| Sterility Success Rate | >99% (208/210 tests) | >99% | >99% | High level of sterility maintained |

Table 2: Contrast Ratio Requirements for Accessibility in Data Visualization [20] [21]

| Element Type | Minimum Contrast Ratio | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Small Text | 4.5:1 | Applies to most body text in figures and dashboards. |

| Large Text | 3:1 | Large text is defined as at least 14pt bold or 18pt regular. |

| Graphical Elements | 3:1 | Applies to non-text elements like charts, graphs, and UI components. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Multi-Lab Plant-Microbiome Study

This protocol summarizes the methodology used to achieve high reproducibility across five independent laboratories [5] [6].

Objective: To test the replicability of synthetic community (SynCom) assembly, plant phenotype responses, and root exudate composition within sterile fabricated ecosystems (EcoFAB 2.0 devices).

Materials (The Scientist's Toolkit): Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

| Item | Function / Rationale | Source in Featured Study |

|---|---|---|

| EcoFAB 2.0 Device | A sterile, fabricated ecosystem providing a controlled habitat for plant growth and microbiome studies. | Provided centrally to all labs [6]. |

| Brachypodium distachyon Seeds | A model grass organism with standardized genetics. | Seeds were freshly collected and shipped from a central source [6]. |

| Synthetic Microbial Community (SynCom) | A defined mix of 17 (or 16) bacterial isolates from a grass rhizosphere. Limits complexity while retaining functional diversity. | SynComs were prepared as 100x concentrated glycerol stocks and shipped on dry ice from a central lab [5] [6]. |

| Murashige and Skoog (MS) Medium | A standardized plant growth medium providing essential nutrients. | Protocol specified exact part numbers and formulations to be used [6]. |

| Data Loggers | To monitor and record growth chamber conditions (temperature, light period) across all participating labs. | Provided in the initial supply package [6]. |

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Device Assembly: Assemble the sterile EcoFAB 2.0 device according to the provided protocol.

- Seed Preparation: Dehusk B. distachyon seeds, perform surface sterilization, and stratify at 4°C for 3 days.

- Germination: Germinate seeds on agar plates for 3 days.

- Transfer: Transfer seedlings to the EcoFAB 2.0 device for an additional 4 days of growth.

- Inoculation: Perform a sterility test and inoculate the SynCom into the EcoFAB device (final inoculum: 1 × 105 bacterial cells per plant).

- Monitoring: Refill water and perform root imaging at three defined timepoints.

- Harvest: Sample roots and media, and harvest plants at 22 days after inoculation (DAI). All samples are collected according to a template and shipped to a central lab for sequencing and metabolomics analysis.

Key Standardization Steps:

- Centralized Materials: Critical components (SynComs, seeds, EcoFABs, data loggers) were distributed from the organizing laboratory.

- Detailed Protocol: A comprehensive protocol with embedded annotated videos was followed by all labs [6].

- Centralized Analysis: To minimize analytical variation, a single laboratory performed all 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing and metabolomic analyses (LC-MS/MS).

Experimental Workflow and Uncertainty Framework Visualization

Implementing Best Practices: Standardized Protocols for Robust Plant Experiments

FAQs on Enhancing Experimental Reproducibility

Why is detailed reporting of biological material origin so critical?

Detailing the geographical source, specific cultivar, and collection method of plant samples is fundamental. This information provides critical context for your findings, as the quality and composition of plant materials can be significantly influenced by their growing conditions and genetic background [22]. For example, research on Fritillariae Cirrhosae Bulbus demonstrated that its alkaloid content is directly regulated by its geographical environment and cultivation practices [22]. Always deposit biological materials in recognized resource centers and provide the accession numbers in your manuscript [23].

What level of detail is required for instrument parameters?

Merely stating the microscope model is insufficient. To ensure another researcher can replicate your work, you must report the exact settings used during data acquisition. For fluorescence microscopy, this includes details like laser power, exposure time, objective lens magnification and numerical aperture, pinhole aperture size (for confocal microscopy), and all filter specifications [24]. This transparency allows others to replicate your imaging conditions exactly and validate your results.

How should I report software and computational methods?

Always specify the software name, exact version number, and the specific settings or parameters used for data analysis [23]. Scripted workflows in languages like R or Python are strongly encouraged over spreadsheet software (e.g., Microsoft Excel) for complex analyses, as they offer superior control, reduce manual errors, and inherently promote reproducibility. When using a script, consider making it available in a public code repository [23].

What is the best practice for sharing raw data?

All newly generated sequences (e.g., DNA, RNA) must be deposited in a publicly accessible repository like GenBank, EMBL-ENA, or DDBJ, with the accession numbers provided in the manuscript [23]. For other data types, such as hyperspectral images or raw metabolomics data, use appropriate public repositories such as the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) and reference the associated BioProject accessions [23]. This practice is vital for open science and allows other researchers to validate and build upon your work.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Experimental Results Between Replicates

- Possible Cause 1: Unrecorded variations in sample growth conditions.

- Solution: Maintain and report detailed records of all environmental factors, including light intensity, photoperiod, temperature, humidity, and soil/composition. Standardize these conditions for all replicates.

- Possible Cause 2: Uncontrolled variation in sample preparation.

- Solution: Develop and provide a Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) for sample preparation. For example, when preparing plant powder for metabolomics, specify the grinding method (e.g., liquid nitrogen), sieve mesh size (e.g., 100-mesh), and storage conditions [22].

- Possible Cause 3: Drift in instrument performance.

- Solution: Implement a regular calibration schedule for all instruments and document the results. Report any calibrations performed immediately before or after your experiments.

Problem: Peer Reviewers Flag a Lack of Methodological Detail

- Issue: The manufacturer of a key chemical reagent was not specified.

- Correction: Report the actual manufacturers of all materials used, not just local suppliers. For example: "Peimisine reference standard (CAS: 19773-24-1) was supplied by Chengdu Alpha Biotech Co., Ltd. (China)" [22].

- Issue: The statistical tests used are named, but their assumptions and justification are not provided.

- Correction: Articulate the statistical tests applied, the assumptions considered (e.g., normality, homogeneity of variance), any corrections for multiple comparisons, and the criteria for significance (e.g., p < 0.05) [23].

- Issue: A custom analysis script was used, but it is unavailable for review.

- Correction: Deposit the script in a public, version-controlled repository (e.g., GitHub, GitLab) and provide the URL in the manuscript. The script should be well-commented to ensure clarity [23].

Problem: Inability to Replicate a Published Bioinformatic Analysis

- Cause: The version of the reference database used for taxonomic assignment was not cited.

- Solution: Clearly cite the reference databases and datasets utilized in your analyses, including version numbers and access dates. For instance, specify if you used the SILVA database for bacterial taxa or UNITE for fungal taxa, along with the specific release version [23].

- Cause: Key parameters for a computational pipeline were not reported.

- Solution: When using analytical platforms, provide extensive methodological details, including the steps of data processing, algorithms applied, and all parameter settings [23].

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Sample Preparation for Plant Metabolomics

This protocol is adapted from methods used in a 2025 study on Fritillariae Cirrhosae Bulbus [22].

- Homogenization: Precisely weigh 0.1 g of plant material that has been ground under liquid nitrogen.

- Metabolite Extraction: Add 500 μL of an 80% methanol aqueous solution. Vortex the mixture thoroughly and incubate it on ice for 5 minutes.

- Clarification: Centrifuge the mixture at 15,000 ×g at 4°C for 20 minutes.

- Dilution: Dilute a portion of the supernatant with water to achieve a final methanol concentration of 53%.

- Final Clarification: Centrifuge the diluted supernatant again at 15,000 ×g at 4°C for 20 minutes.

- Sterile Filtration: Filter the final supernatant through a 0.22 μm membrane filter.

- Analysis: The sample is now ready for analysis via UPLC-MS/MS or other profiling techniques.

Protocol 2: Best Practices in Plant Fluorescence Microscopy

Following established guidelines is key to obtaining high-quality, interpretable images [24].

Experimental Design:

- Pilot Study: Perform a small-scale pilot project to optimize conditions before a full experiment.

- Control Samples: Always include appropriate controls (e.g., unstained, wild-type, mock-treated).

- Instrument Selection: Choose the right microscope for your question (see Workflow Diagram below).

Image Acquisition:

- Avoid Saturation: Set laser power and gain to ensure no pixel values are overexposed.

- Maximize Signal-to-Noise: Optimize settings to collect a clear signal while minimizing background.

- Document Everything: Record all instrument parameters, objectives, and software settings.

Image Processing & Reporting:

- Transparency: Any image adjustments (e.g., deconvolution, background subtraction) must be disclosed and their parameters stated.

- Data Sharing: Make original, unprocessed images available upon request or via public repositories.

Workflow Diagrams

Dot Script for Experimental Design Workflow

Dot Script for Data Reporting & Sharing Pipeline

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Materials for Plant Metabolomics and Traceability Studies

| Item Name | Function / Role | Example from Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| HPLC-Grade Reference Standards | Serves as a calibrated benchmark for precise identification and quantification of target compounds. | Peimisine, imperialine; used for targeted alkaloid quantification [22]. |

| Certified Reference Material (CRM) Stock Solutions | Provides a traceable and accurate standard for calibrating elemental analysis instruments. | Single-element (Na, K) and mixed-element stock solutions for mineral nutritional element analysis [22]. |

| Chromatography-Grade Solvents | Ensures high purity to prevent contaminants from interfering with sensitive mass spectrometry analysis. | Methanol, formic acid, ammonium acetate, and acetonitrile for UPLC-MS/MS [22]. |

| Public Taxonomic Databases | Provides a curated reference for assigning taxonomy to sequence data, crucial for microbiome studies. | SILVA (for bacterial taxa) and UNITE (for fungal taxa) [23]. |

| Public Sequence Repositories | Archives raw sequencing data, enabling validation, meta-analysis, and reuse by the global scientific community. | NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA), GenBank [23]. |

Standardizing Plant-Microbiome Studies with Synthetic Communities and EcoFABs

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guidance and best practices for researchers using Synthetic Communities (SynComs) and Fabricated Ecosystem (EcoFAB) devices to enhance reproducibility in plant-microbiome experiments.

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting

Q1: Our SynCom fails to establish the expected community structure on plant roots, with one species dominating unexpectedly. How can we troubleshoot this?

This is a common challenge in community assembly. A recent multi-laboratory study identified several factors to investigate:

- Check for Competitive Dominance: Some bacterial strains possess inherent competitive advantages. Paraburkholderia sp. OAS925 was consistently found to dominate root colonization across five independent laboratories, drastically shifting the final microbiome composition regardless of the initial equal inoculum ratio [5] [6]. Conduct comparative genomics on your SynCom members to identify potential traits like motility, resource use efficiency, or antibiotic production.

- Verify Inoculum Preparation: Ensure accurate cell density measurements. The referenced protocol used optical density at 600 nm (OD600) calibrated to colony-forming unit (CFU) counts to standardize the final inoculum to 1 × 10^5 bacterial cells per plant [6]. Inaccurate cell counts can skew initial community ratios.

- Monitor Environmental Parameters: Factors like pH can directly influence colonization success. Follow-up in vitro assays confirmed the pH-dependent colonization ability of the dominant Paraburkholderia strain [5] [25]. Maintain consistent and documented growth chamber conditions.

Q2: We observe inconsistent plant phenotypes (e.g., biomass) between replicate experiments. How can we improve consistency?

Variability in plant growth can confound microbiome studies. Focus on standardizing the host plant environment.

- Standardize Plant Growth Conditions: In a multi-lab trial, differences in growth chamber conditions (e.g., light quality [fluorescent vs. LED], intensity, and temperature) were linked to observable variability in plant biomass measurements [6]. Use data loggers to continuously monitor and record these parameters.

- Use Sterile, Controlled Devices: The EcoFAB platform is designed for this purpose. In the ring trial, less than 1% of sterility tests showed contamination (2 out of 210 tests), confirming the system's reliability for axenic growth [6]. Always include axenic (mock-inoculated) controls to baseline plant physiology without microbes.

- Follow Detailed Growth Protocols: Adhere to a standardized protocol from seed sterilization to harvest. The reproducible study used a detailed protocol with specific steps for seed dehusking, surface sterilization, stratification, and germination before transfer to EcoFABs [6].

Q3: What are the most critical steps to ensure cross-laboratory reproducibility in a SynCom experiment?

Achieving inter-laboratory replicability requires meticulous standardization at every stage.

- Centralize Key Materials: To minimize variation, the organizing laboratory should provide all critical components, including SynCom inoculum, seeds, EcoFAB devices, and other specific supplies to all participating labs [5] [6].

- Centralize Downstream Analyses: To minimize analytical variation, have a single laboratory perform all sequencing and metabolomic analyses [5] [6].

- Provide Video-Annotated Protocols: Written protocols can be interpreted differently. The successful ring trial used detailed protocols with embedded annotated videos to demonstrate techniques visually, ensuring all labs performed tasks the same way [6].

Experimental Protocols & Benchmarking Data

Standardized Protocol for SynCom Assembly in EcoFAB 2.0

This methodology has been validated across five laboratories for studying the model grass Brachypodium distachyon [5] [6].

Key Steps:

- EcoFAB 2.0 Assembly: Assemble the sterile device according to the provided instructions.

- Plant Material Preparation:

- Dehusk B. distachyon seeds.

- Surface-sterilize seeds.

- Stratify at 4°C for 3 days.

- Germinate on agar plates for 3 days.

- Transfer to EcoFAB: Aseptically transfer 3-day-old seedlings to the EcoFAB 2.0 device.

- Grow for an additional 4 days before inoculation.

- SynCom Inoculation:

- Prepare SynCom from glycerol stocks shipped on dry ice.

- Resuspend and dilute to a final density of 1 × 10^5 CFU/mL using pre-calibrated OD600 to CFU conversions.

- Inoculate into the EcoFAB device and perform a sterility test.

- Growth and Monitoring:

- Maintain plants for 22 days after inoculation (DAI).

- Refill water and perform root imaging at multiple timepoints.

- Sampling:

- At 22 DAI, harvest plant shoots and roots for biomass analysis.

- Collect roots and media for 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing.

- Collect filtered media for metabolomics (e.g., LC-MS/MS).

The full detailed protocol is available at protocols.io: https://dx.doi.org/10.17504/protocols.io.kxygxyydkl8j/v1 [6].

Quantitative Benchmarking Data from a Multi-Laboratory Ring Trial

The following table summarizes key quantitative outcomes observed across five independent laboratories, providing expected benchmarks for your experiments [6].

| Parameter | Observation | Notes / Variability |

|---|---|---|

| Sterility Success Rate | 99% (208/210 tests) | Contamination was minimal when protocol was followed [6]. |

| SynCom Dominance Effect | Paraburkholderia sp. reached 98 ± 0.03% relative abundance in SynCom17. | Extreme dominance was reproducible across all labs [6]. |

| Community Variability | Higher variability in SynCom16 (without Paraburkholderia). | Dominant taxa varied more across labs (e.g., Rhodococcus sp. 68 ± 33%) [6]. |

| Plant Phenotype Impact | Significant decrease in shoot fresh/dry weight with SynCom17. | Some lab-to-lab variability observed, attributed to growth chamber differences [6]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details essential materials for setting up reproducible plant-microbiome experiments with SynComs and EcoFABs.

| Item | Function / Purpose | Examples / Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| EcoFAB Device | A sterile, fabricated ecosystem providing a controlled habitat for studying plant-microbe interactions in a reproducible laboratory setting [5] [26]. | EcoFAB 2.0 (for model grasses like Brachypodium), EcoFAB 3.0 (for larger plants like sorghum) [6] [26]. |

| Standardized SynCom | A defined synthetic microbial community that reduces complexity while maintaining functional diversity, enabling mechanistic studies [5] [27]. | e.g., 17-member bacterial community for B. distachyon available from public biobanks (DSMZ) [5]. |

| Model Plant | A well-characterized plant species with a short life cycle and genetic tools, ideal for standardized research. | Brachypodium distachyon (model grass), Arabidopsis thaliana, or engineered lines of sorghum [5] [26]. |

| Curated Protocols | Detailed, step-by-step experimental procedures, often with video annotations, to ensure consistent technique across users and laboratories [5] [6]. | Available on platforms like protocols.io; specify part numbers for labware to control variation [6]. |

Workflow and Decision Diagrams

SynCom Experimental Workflow

Troubleshooting SynCom Assembly

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Imaging Issues and Solutions

| Problem Category | Specific Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Image Quality | Fluorescence signal is dark or poor contrast [28] | • Low numerical aperture (NA) objective• Mismatched filter and reagent [28]• Inappropriate camera settings [28] | • Use highest NA objective possible [29] [28]• Verify filter spectra overlap reagent's excitation/emission peaks [28]• Increase exposure time or use camera binning [28] |

| Image is blurry or out-of-focus [28] | • Thick plant samples causing out-of-focus light [24]• Incorrect cover glass thickness [28] | • Use confocal microscopy for optical sectioning [24]• Apply deconvolution algorithms to widefield images [24] [30]• Adjust correction ring for cover glass thickness [28] | |

| Signal Fidelity | Photobleaching occurs [29] [28] | • Prolonged exposure to excitation light [29]• High illumination intensity [31] | • Add anti-fading reagents to sample [31]• Reduce light intensity and exposure time [31]• Use spinning disk confocal to reduce exposure [24] |

| High background or autofluorescence [24] | • Chlorophyll, cell walls, or cuticle autofluorescence [24]• Incomplete washing of excess fluorochrome [31] | • Use fluorophores with emission in far-red spectrum [24]• Thoroughly wash specimen after staining [31]• Use objectives with low autofluorescence [29] | |

| Equipment & Setup | Uneven illumination or flickering [31] | • Aging lamp (mercury or metal halide) [31]• Dirty optical components | • Replace light source if flickering occurs [31]• Clean optical elements with appropriate solvents [31] |

Optimizing Microscope Configuration

| Component | Selection Criteria | Impact on Image Quality |

|---|---|---|

| Objective Lens | • High Numerical Aperture (NA) [29]• Low Magnification Photoeyepiece [29]• Coverslip Correction [28] | • Image brightness varies as the fourth power of the NA [29]• Brightness varies inversely as the square of the magnification [29] |

| Light Source | • Mercury/Xenon for broad spectrum [31]• LED for specific wavelengths [28] | • Mercury lamps provide high energy for dim specimens [31]• Heat filter required to prevent damage [31] |

| Camera | • Cooled CCD monochrome for low light [28] [32]• High Quantum Efficiency (QE) [32] | • Cooling reduces dark current noise [28] [32]• Monochrome cameras have higher sensitivity than color [28] |

| Filters | • High transmission ratio [28]• Match excitation/emission spectra of fluorophore [28] | • Critical for separating weak emission light from excitation light [31] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How can I reduce photobleaching in my live plant samples?

Photobleaching (or dye photolysis) is the irreversible destruction of a fluorophore under excitation light. It is caused primarily by the photodynamic interaction between the fluorophore and oxygen [29]. To minimize it:

- Limit Exposure: Reduce light intensity to the lowest level possible and only expose the sample when acquiring an image by using the microscope's shutter [31].

- Use Anti-fading Reagents: Add antifading reagents to your mounting medium to slow the photobleaching process [31].

- Choose Microscope Wisely: Spinning disk confocal microscopy generally causes less photobleaching compared to laser scanning confocal microscopy (LSCM) due to faster imaging and lower light dose [24].

What is the best way to deal with plant autofluorescence?

Plant tissues are notorious for autofluorescence, particularly from chlorophyll, cell walls, and waxy cuticles [24].

- Spectral Separation: Choose fluorescent probes (e.g., those emitting in the far-red spectrum) whose emission does not overlap with the common autofluorescence signatures of chlorophyll (red) and cell walls (green) [24].

- Sample Preparation: Ensure thorough washing after staining to remove any unbound fluorochrome that can contribute to background [31].

- Control Experiments: Always include an unstained control sample to identify the level and color of inherent autofluorescence for your specific tissue.

Why is my fluorescence signal so weak, and how can I improve it?

A dim signal can stem from multiple factors. systematically check your setup:

- Objective Lens: This is often the most critical factor. Always use the objective with the highest numerical aperture (NA) you can, as image brightness in reflected light fluorescence varies as the fourth power of the NA [29].

- Magnification: Keep the total magnification on the camera sensor as low as possible, as image brightness decreases with the square of the magnification [29]. Use low magnification projection lenses [29] [31].

- Filter Sets: Confirm that your excitation and emission filter spectra have a high transmission ratio and properly match the excitation and emission peaks of your fluorophore [28].

- Camera Settings: Optimize exposure time, gain, and consider using binning to increase signal at the cost of some spatial resolution [28].

Should I use a widefield or confocal microscope for my plant sample?

The choice depends on your sample thickness and biological question.

- Widefield Microscopy: Best for thin samples or high-speed screening. It is more accessible and affordable. For thicker samples, computational deconvolution can be applied to remove out-of-focus blur and improve contrast [24] [30].

- Laser Scanning Confocal Microscopy (LSCM): Ideal for thicker samples as it provides optical sectioning by using a pinhole to reject out-of-focus light, resulting in clearer images [24].

- Spinning Disk Confocal Microscopy: The best choice for imaging fast dynamic processes (e.g., calcium signaling, vesicle trafficking) in live samples, as it allows for much higher acquisition speeds with reduced photobleaching [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

| Item | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|

| High-NA Objectives | Objectives with high numerical aperture (e.g., 40x/NA 0.95 vs. 40x/NA 0.65) dramatically increase collected light, reducing exposure times and photobleaching. Use objectives designed for fluorescence with low autofluorescence [29]. |

| Anti-fading Mounting Media | These reagents slow the rate of photobleaching by reducing the interaction between the excited fluorophore and oxygen, preserving signal intensity during prolonged imaging [31]. |

| Non-Fluorescent Immersion Oil | Standard immersion oils can autofluoresce. Using specially formulated non-fluorescent oil minimizes this background noise, especially with high-NA oil immersion objectives [29]. |

| Validated Filter Sets | Filter cubes (excitation filter, emission filter, dichroic mirror) must be matched to the fluorophore's spectra. Hard-coating filters with high transmission ratios provide brighter images [28]. |

Experimental Workflow for Reproducible Plant Fluorescence Imaging

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for designing and executing a reproducible fluorescence imaging experiment in plant science.

Transitioning from spreadsheet-based analysis to scripted workflows in R and Python represents a critical step forward in addressing the reproducibility crisis documented across scientific disciplines, including plant science and agricultural research [2] [33] [34]. This technical support center provides plant scientists with practical troubleshooting guides and FAQs to overcome common barriers during this transition, enabling more transparent, reproducible, and efficient research practices that are essential for reliable drug development and sustainable agriculture innovations.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why move beyond graphical user interface (GUI) tools like Excel to R or Python? Scripted analysis provides automation, creates a verifiable record of all data processing steps, and enables easy repetition and adjustment of analyses [35]. This is a foundational practice for reproducible research, ensuring that anyone can trace how results were derived from raw data.

FAQ 2: What is the difference between repeatability, replicability, and reproducibility? These terms form a hierarchy of confirmation in research [2] [34]:

- Repeatability: The same team can reproduce its own findings using the same experimental setup.

- Replicability: A different team can reproduce the findings of a previous study using the same source materials and experimental setup.

- Reproducibility: An independent team can produce similar results using a different experimental setup (e.g., different code, locations, or conditions).

FAQ 3: How can scripted analysis help with the reproducibility crisis in plant science? Non-reproducible research wastes resources and undermines public trust [34]. Scripted analysis directly addresses common causes of irreproducibility by ensuring analytic transparency, providing a complete record of data processing steps, and facilitating the sharing of code and methods [36] [34].

FAQ 4: What are the first steps to making my workflow reproducible? Begin by using expressive names for files and directories, protecting your raw data from modification, and thoroughly documenting your workflows with tools like RMarkdown or Jupyter Notebooks [37].

Troubleshooting Guides

Interpreting and Fixing Common Error Messages

A. Object or Module Not Found

- Problem: In R, you encounter

Error: object 'tets' not found. In Python, you getModuleNotFoundError: No module named 'torch'. - Causes: Typically caused by misspelling an object name in R, or by incorrect Python environment configuration or not installing the required package in Python [38] [39].

- Solutions:

- R: Check for typos in the object name and ensure you have run the code that creates the object (e.g., a data frame or variable) [38].

- Python: Verify that the correct Python environment is loaded (e.g., in RStudio, check

reticulate::py_config()). Install the missing module usingconda installorpip installfrom your terminal [39].

B. Dimension Mismatch

- Problem: In R, you see an error like

replacement has 4 rows, data has 5when trying to add a column to a data frame [38]. - Causes: You are trying to combine data structures of incompatible sizes.

- Solutions:

- Check the dimensions (e.g., using

dim(),nrow(), orlength()) of all objects involved in the operation. - Ensure that the vectors or lists you are combining have the same number of elements or are multiples of each other.

- Check the dimensions (e.g., using

C. Syntax Errors

- Problem: Unexpected

)orundefined columns selectederror in R [38]. - Causes: Unclosed parentheses, brackets, or quotation marks. For the column error, it often means you forgot a comma inside square brackets when subsetting a data frame.

- Solutions:

- Use RStudio's syntax highlighting, which will highlight matching parentheses/brackets.

- Carefully check the syntax of your subsetting operation. For a data frame, it should be

df[rows, columns].

Troubleshooting a Loop

When a loop in R fails with an error, you can identify the problematic iteration.

- Problem: A loop stops with an error, such as

non-numeric argument to binary operator[38]. - Solution:

- After the error, check the value of the loop index (

i). This tells you which iteration failed [38]. - Manually set

ito the failed value (e.g.,i <- 6). - Run the code inside the loop one line at a time to identify the exact operation that fails. This often reveals that a particular list element or row contains unexpected data types (e.g., a character where a number is expected) [38].

- After the error, check the value of the loop index (

Package and Environment Management

- Problem: A function from a specific package does not work as expected, or you get an error about a conflicting function name.

- Causes: The function might exist in multiple loaded packages, and R is using the one from a different package than intended. The order in which packages are loaded matters [38].

- Solutions:

- Use the syntax

package::function()to explicitly state which package a function should come from (e.g.,dplyr::filter()instead of justfilter()). This removes ambiguity [38]. - If you encounter a "package not found" error, ensure the package is installed in your current R library using

install.packages("package_name").

- Use the syntax

General Workflow for Troubleshooting

Follow this general workflow when you encounter an error in a scripted analysis:

Essential Tools for Reproducible Scripted Analysis

The table below outlines key tools and practices that form the foundation of a reproducible scripted research workflow.

| Tool / Practice | Function | Role in Reproducibility |

|---|---|---|

| Version Control (Git/GitHub) | Tracks all changes to code and scripts over time [36] [35]. | Prevents ambiguity by linking specific results to specific versions of code and data [36]. |

| Dynamic Documents (RMarkdown/Quarto/Jupyter) | Weave narrative text, code, and results (tables/figures) into a single document [36] [37]. | Ensures results in the report are generated directly from the code, eliminating copy-paste errors [36]. |

| Dependency Management (e.g., renv, conda) | Records the specific versions of R/Python packages used in an analysis [36]. | Prevents errors caused by using different versions of software packages in the future [36]. |

| Project-Oriented Workflow | Organizes a project with a standard folder structure (e.g., data/raw, data/processed, scripts, outputs) [37] [35]. |

Keeps raw data separate and safe, making the workflow easy to navigate and rerun [37]. |

A Reproducible Workflow for Plant Science Experiments

Adopting a structured, scripted workflow is key to reproducible plant science experiments, from field data collection to final analysis and reporting.

Research Reagent Solutions: Digital Tools for Reproducible Analysis

This table lists essential "digital reagents" – the software tools and packages required for a reproducible plant science data analysis workflow.

| Tool / Package | Function | Application in Plant Science |

|---|---|---|

| RStudio IDE / Posit | An integrated development environment for R. | Provides a user-friendly interface for writing R code, managing projects, and viewing plots and data. |

| Jupyter Notebook/Lab | An open-source web application for creating documents containing code, visualizations, and narrative text. | Ideal for interactive data analysis and visualization in Python. |

tidyverse (R) |

A collection of R packages (e.g., dplyr, ggplot2) for data manipulation, visualization, and import. |

The core toolkit for cleaning, summarizing, and visualizing experimental data in R. |

pandas (Python) |

A Python package providing fast, powerful, and flexible data structures and analysis tools. | The fundamental library for working with structured data (like field trial results) in Python. |

Git & GitHub |

A version control system (Git) and a cloud-based hosting service (GitHub). |

Essential for tracking changes to analysis scripts and collaborating with other researchers. |

renv (R) / conda (Python) |

Dependency management tools that create isolated, reproducible software environments for a project. | Ensures that your analysis runs consistently in the future, even as package versions change. |

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

This section addresses common challenges in LC-MS/MS-based phytohormone profiling to enhance methodological reproducibility.

Sample Preparation and Contamination

Q: My analysis shows high background noise and inconsistent results. What could be the cause? A: This is often due to contamination or insufficient sample cleanup. To avoid this:

- Employ a divert valve: This simple component prevents non-interesting compounds and the high organic solvent portion of the gradient from entering the mass spectrometer, significantly reducing source contamination [40].

- Use thorough sample preparation: For complex plant matrices, simple filtration may not suffice. Implement robust techniques like Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) to remove dissolved contaminants and matrix interferences [40] [41].

- Check labware: Contaminants from plasticware, such as plasticizers, can leach into samples. Use high-quality, MS-grade solvents and consider glass or specialized containers [41].

Q: How can I mitigate matrix effects that impact quantification accuracy? A: Matrix effect is interference from the sample matrix on analyte ionization and detection [42].

- Use internal standards: Stable isotope-labeled internal standards (e.g., salicylic acid D4) are ideal as they correct for losses during preparation and ionization variability [43] [41].

- Employ matrix-matched calibration: Prepare your calibration standards in a matrix similar to your sample to compensate for suppression or enhancement effects [41].

- Evaluate during validation: Assess matrix effect by analyzing samples from different individual matrix sources/lots spiked with known analyte concentrations [42].

Mobile Phase and Instrument Performance

Q: What mobile phase additives are appropriate for LC-MS/MS phytohormone analysis? A: Use only volatile additives to prevent ion source contamination [40].

- Acids and bases: 0.1% formic acid or 0.1% ammonium hydroxide (if the column tolerates high pH) [40].

- Buffers: 10 mM ammonium formate or acetate. Avoid non-volatile buffers like phosphate [40].

- Purity: Use the highest purity additives available. A good principle is: "If a little bit works, a little bit less probably works better" to minimize background noise [40].

Q: My signal is unstable. How can I determine if the problem is with my method or the instrument? A: Implement a benchmarking method.

- Procedure: Regularly run five replicate injections of a standard compound like reserpine to monitor parameters like retention time, repeatability, and peak height [40].

- Troubleshooting: If a problem occurs, run your benchmark. If it performs as expected, the issue lies with your specific method or samples. If the benchmark fails, the problem is likely with the instrument system itself [40].

Q: Should I frequently vent the mass spectrometer for maintenance? A: No. Mass spectrometers are most reliable when left running. Venting increases wear, especially on expensive components like the turbo pump, which is designed to operate under high vacuum. The rush of atmospheric air during startup places significant strain on the pump's vanes and bearings [40].

Method Validation and Data Quality

Q: What are the essential parameters to validate for a reproducible LC-MS/MS method? A: For reliable and reproducible results, your method validation must assess several key characteristics [42]:

Table 1: Essential Validation Parameters for LC-MS/MS Methods

| Parameter | Description | Why it Matters for Reproducibility |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Closeness of measured value to the true value. | Prevents errors in final concentration, crucial for dose-related decisions [42]. |

| Precision | Agreement between repeated measurements of the same sample. | Reduces uncertainty and ensures method reproducibility [42]. |

| Specificity | Ability to accurately measure the target analyte among other components. | Ensures results are not skewed by matrix interferences [42]. |

| Linearity | Produces results proportional to analyte concentration over a defined range. | Confirms the method works accurately across the intended concentration range [42]. |

| Quantification Limit | Lowest concentration that can be reliably measured. | Defines method sensitivity and the lowest reportable value [42]. |

| Matrix Effect | Impact of the sample matrix on ionization efficiency. | Identifies suppression/enhancement that can lead to inaccurate quantification [42]. |

| Recovery | Efficiency of the extraction process. | Indicates how well the sample preparation releases the analyte from the matrix [42]. |

| Stability | Analyte integrity under storage and processing conditions. | Ensures results are consistent over the timeline of the analysis [42]. |

Q: What criteria should I check in each analytical run (series validation)? A: Dynamic validation of each run is critical for ongoing data quality. Key checklist items include [44]:

- Acceptable calibration function: Predefined pass criteria for slope, intercept, and R² must be met [44].

- Verification of LLoQ/ULoQ: The lowest and highest calibrators must meet signal intensity (e.g., signal-to-noise) and accuracy criteria to confirm the analytical measurement range [44].

- Calibrator residuals: Back-calculated concentrations of calibrators should typically be within ±15% of expected values (±20% at the LLoQ) [44].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: A Unified Workflow

The following workflow is adapted from a study profiling phytohormones (ABA, SA, GA, IAA) across five distinct plant matrices (cardamom, dates, tomato, Mexican mint, aloe vera) using a unified LC-MS/MS platform [43].

- Homogenization: Flash-freeze plant tissue with liquid nitrogen and homogenize thoroughly using a mortar and pestle.

- Weighing: Accurately weigh approximately 1.0 g ± 0.1 g of homogenized material.

- Matrix-Specific Extraction:

- Use solvent mixtures tailored to each plant matrix (see Reagent Table below).

- For challenging matrices like dates (high sugar content), a two-step extraction with acetic acid followed by 2% HCl in ethanol may be required.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge extracts at 3000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C.

- Internal Standard Addition: Add a stable isotope-labeled internal standard (e.g., salicylic acid D4) to correct for variability.

- Filtration and Dilution: Filter the supernatant through a 0.22 µm syringe filter. Dilute with mobile phase as needed for compatibility with LC-MS/MS.

- Instrumentation: Shimadzu LC-30AD Nexera X2 system coupled with an LC-MS-8060 mass spectrometer.

- Column: ZORBAX Eclipse Plus C18 (4.6 x 100 mm, 3.5 µm).

- Mobile Phase: LC-MS grade solvents and volatile additives (e.g., 0.1% formic acid).

- Mass Spectrometry: Optimized source settings (voltages, temperatures) via autotune and manual compound-specific tuning. Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) mode is used for quantification.

Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists essential materials for implementing the unified LC-MS/MS profiling method.

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Phytohormone Profiling

| Item | Function / Role | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Abscisic Acid (ABA) | Analyte; stress response phytohormone [43]. | Sigma-Aldrich |

| Salicylic Acid (SA) | Analyte; involved in disease resistance [43]. | Sigma-Aldrich |

| Gibberellic Acid (GA) | Analyte; regulates growth and development [43]. | Sigma-Aldrich |

| Indole-3-acetic Acid (IAA) | Analyte; primary auxin for growth [43]. | Sigma-Aldrich |

| Salicylic Acid D4 | Internal Standard; corrects for variability [43]. | Sigma-Aldrich |

| LC-MS Grade Methanol | Solvent; mobile phase and extraction [43]. | Supelco |

| LC-MS Grade Water | Solvent; mobile phase [43]. | Milli-Q System |

| Formic Acid | Mobile Phase Additive; promotes ionization [43]. | Fluka |

| C18 LC Column | Chromatography; separates analytes [43]. | ZORBAX Eclipse Plus, 3.5 µm |

| 0.22 µm Syringe Filter | Sample Cleanup; removes particulates [43]. | N/A |

Series Validation Checklist

For every analytical run, confirm the following to ensure data integrity and reproducibility [44]:

- Calibration: A full or minimum calibration function is established and meets predefined pass criteria for slope, intercept, and R².

- LLoQ/ULoQ: The signal at the Lower Limit of Quantification is sufficient (e.g., meets S/N criteria), and the Analytical Measurement Range is verified.

- Calibrator Accuracy: Back-calculated concentrations for calibrators are within ±15% of target (±20% at LLoQ).

- Quality Controls: QC samples at low, medium, and high concentrations show accuracy and precision within acceptable limits.

- Blank Analysis: Blanks are clean, with no significant carry-over from the previous injection.

Overcoming Common Obstacles: Strategies for Troubleshooting Irreproducible Results

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is documenting environmental variability so critical for the reproducibility of my plant experiments?