AI and Data Science in Plant Physiology: From Genomic Prediction to Precision Phenotyping

This article explores the transformative impact of data science and artificial intelligence on modern plant physiology research.

AI and Data Science in Plant Physiology: From Genomic Prediction to Precision Phenotyping

Abstract

This article explores the transformative impact of data science and artificial intelligence on modern plant physiology research. It provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and scientists, covering foundational AI concepts and their specific applications in decoding complex plant biological processes. The content delves into practical machine learning methodologies for genomic prediction, stress response monitoring, and high-throughput phenotyping, while also addressing critical challenges such as data scarcity, model interpretability, and biological complexity. Through comparative analysis of statistical versus machine learning approaches and evaluation of emerging AI architectures, this review synthesizes current capabilities and future directions, highlighting how data-driven insights are accelerating crop improvement and sustainable agricultural innovation.

The Data Science Revolution in Plant Systems Biology

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) is fundamentally transforming plant science research. This paradigm shift addresses critical agricultural challenges—such as climate change, global food security, and sustainable resource management—by converting complex, high-dimensional plant data into actionable biological insights. Framed within the broader context of data science applications in plant physiology, this technical guide details how AI/ML methodologies are revolutionizing key areas including high-throughput phenotyping, plant genomics, and predictive breeding. The convergence of AI with other disruptive technologies like CRISPR and automation is forging a new era of data-driven plant bio-discovery, accelerating the development of resilient, high-yielding crops essential for a growing global population.

Core AI Concepts and Their Application in Plant Science

AI in plant science encompasses a suite of computational techniques designed to mimic human intelligence for learning, reasoning, and decision-making from large, complex datasets. The foundational concepts are hierarchically structured, each playing a distinct role in data analysis and model building [1].

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is the overarching field focused on creating systems capable of performing tasks that typically require human intelligence. Within AI, Machine Learning (ML) provides the statistical foundation, enabling computers to identify patterns in data and make predictions without being explicitly programmed for each task. ML is further divided into supervised learning (using labeled data for classification and regression) and unsupervised learning (discovering hidden patterns from unlabeled data) [2].

A subset of ML, Deep Learning (DL) utilizes layered neural network architectures (e.g., Convolutional Neural Networks [CNNs] for image analysis, Recurrent Neural Networks [RNNs] for sequential data) to automatically learn intricate patterns and hierarchical features from raw, high-dimensional data [1] [3]. Explainable AI (XAI) addresses the "black box" nature of complex models like DL by enhancing the transparency and interpretability of their decision-making processes, which is critical for building trust and deriving biological insights in plant science [3]. Finally, specialized frameworks like Federated Learning support collaborative model training across distributed data sources (e.g., multiple research institutions) while maintaining data privacy and security [1].

Table 1: Core AI/ML Concepts and Their Applications in Plant Science

| AI Concept | Key Function | Exemplary Application in Plant Science |

|---|---|---|

| Machine Learning (ML) | Identifies patterns and makes predictions from data. | Genomic selection; identification of genetic markers linked to desirable traits [1]. |

| Deep Learning (DL) | Uses neural networks to automatically learn features from complex raw data (e.g., images). | High-throughput phenotyping; leaf disease detection from drone imagery [2] [4]. |

| Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) | A class of DL particularly effective for image processing and classification. | Classification of leaf morphology; segmentation of plant structures from RGB images [2] [5]. |

| Explainable AI (XAI) | Makes the decisions of complex AI models interpretable to humans. | Identifying which visual features a model uses to diagnose plant stress, relating AI output to plant physiology [3]. |

| Generative Models | Generates synthetic data that mimics real-world observations. | Creating synthetic plant images to augment training datasets for rare disease phenotypes [1]. |

Key Application Domains and Experimental Methodologies

AI-Driven High-Throughput Phenotyping (HTP)

Core Concept: High-throughput phenotyping uses automated, often non-destructive, imaging systems to characterize plant traits such as growth, architecture, and health at scale. AI, particularly DL, is critical for extracting meaningful biological information from the massive image datasets these systems generate [2].

Experimental Protocol: Image-Based Phenotyping for Drought Stress Response

- Platform and Data Acquisition: Utilize ground-based (e.g., LemnaTec Scanalyzer) or aerial platforms (UAVs/drones) equipped with RGB, multispectral, or hyperspectral sensors. Images of plants (e.g., Populus Trichocarpa genotypes) are collected over time under controlled drought and well-watered conditions [2] [5]. High-precision GPS tags each image with location data.

- Image Pre-processing: Apply standardization techniques to correct for variations in lighting and scale. For field-based images, leverage GPS-encoded EXIF data for georeferencing.

- Feature Extraction and Analysis using Deep Learning:

- Task 1: Structure and Morphology: Train a CNN (e.g., U-Net architecture) to perform image segmentation, isolating individual leaves from the background. The model can then classify leaves by shape and morphology across different genotypes [5].

- Task 2: Stress Classification: Use a separate CNN or a multi-task learning framework to classify plants based on their cultivation condition (e.g., 'drought' vs. 'control'). The model learns to correlate visual features like leaf color, wilting, and size with water availability [5].

- Task 3: Data Integration: Integrate extracted phenotypic data with secondary data sources, such as soil maps and daily weather data, to find correlations between phenotype, genotype, and environment [5].

- Validation: Compare AI-derived trait measurements (e.g., leaf area, disease score) with manual measurements performed by domain experts to validate model accuracy.

AI-HTP Workflow

AI in Plant Genomics and Functional Genomics

Core Concept: AI and ML models decipher genomic sequences to identify genes, predict gene function, and link genetic markers to economically important traits, thereby accelerating the development of improved crop varieties [1] [6].

Experimental Protocol: Gene Function Prediction and Pathway Analysis

- Data Collection and Genome Sequencing: Perform whole-genome sequencing of the target medicinal or crop plant (e.g., Salvia miltiorrhiza or Panax ginseng) to obtain the raw DNA sequence. Collect complementary transcriptomic (RNA-Seq) and metabolomic data to profile gene expression and metabolite production [6].

- Variant Calling and Genome Annotation: Use a combination of traditional variant callers (e.g., GATK) and DL-based tools like DeepVariant. DeepVariant treats aligned sequencing data as images and uses a CNN to classify sequence changes (SNPs, indels) with high accuracy, transforming variant calling into an image classification task [6].

- Gene Function Prediction: Apply ML models such as Support Vector Machines (SVMs) or DL models to predict gene function. These models are trained on sequence features (e.g., k-mers, codon usage) and expression patterns from known genes to annotate novel genes, such as those involved in drought resistance or secondary metabolite biosynthesis [7] [6].

- Metabolic Pathway Reconstruction: Utilize tools like ClusterFinder or DeepBGC (which use Hidden Markov Models and DL) to identify Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs) in the genome. Integrate this with metabolomic data to reconstruct pathways for key therapeutic compounds (e.g., tanshinones, ginsenosides) [6]. Protein structure prediction tools like AlphaFold2 can be used to model the 3D structure of enzymes within these pathways to inform metabolic engineering strategies [6].

Table 2: Key AI Tools and Data Types in Plant Genomics

| Research Activity | Key AI/Bioinformatics Tool | Input Data Type | Output/Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variant Calling | DeepVariant (CNN) | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) reads | High-accuracy identification of SNPs and indels [6]. |

| Genome Annotation | Support Vector Machines (SVM) | DNA sequence features, expression patterns | Prediction of gene function for novel sequences [6]. |

| Protein Structure Prediction | AlphaFold2 (DL) | Amino acid sequence | 3D protein structure model for enzyme engineering [6]. |

| Pathway Reconstruction | DeepBGC (DL) | Genomic sequence, metabolomic data | Identification of biosynthetic gene clusters for secondary metabolites [6]. |

| Multi-omics Integration | iDREM, OPLS | Transcriptomic, proteomic, metabolomic data | Construction of integrated gene regulatory and metabolic networks [6]. |

Genomic Analysis Pipeline

The Integrated Future: AI, Automation, and Gene Editing

The most powerful advancements occur at the intersection of AI, automation, and genome editing (e.g., CRISPR/Cas9), creating a closed-loop Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle for plant bio-engineering [8].

In this paradigm:

- Design: AI algorithms analyze multi-omics data to design optimal CRISPR/Cas9 targets for trait enhancement and predict the ideal tissue culture media formulations for regenerating edited plants.

- Build: Robotic automation systems (e.g., RoBoCut) execute precise tissue culture protocols, handling plantlets and preparing media with minimal human intervention.

- Test: Automated sensors and AI-powered machine vision non-invasively monitor the growth and health of edited plantlets in bioreactors, generating high-throughput phenotypic data.

- Learn: All data from the "Test" phase is fed back to the AI models, which continuously learn and refine the designs and protocols for the next cycle, dramatically accelerating the pace of innovation [8].

This integration is pivotal for overcoming the challenge of "recalcitrance"—where many important crops resist regeneration in tissue culture. AI-driven platforms like the TiGER workflow can screen thousands of chemical and environmental conditions to identify those that unlock regeneration for recalcitrant species, as demonstrated by the successful regeneration of gene-edited strawberry plants from single cells [8].

Design-Build-Test-Learn Cycle

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for AI-Driven Plant Science

| Reagent / Platform | Function / Application | Role in AI/ML Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Temporary Immersion System (TIS) e.g., BioCoupler | Provides scalable, automated liquid culture environment for plantlets. | Generates standardized, high-volume growth data for AI model training on plant development [8]. |

| Single-Use Bioreactors (SUBs) | Disposable culture vessels for sterile plant propagation. | Enables scalable data generation under controlled conditions; reduces contamination variable in datasets [8]. |

| RoBoCut System | Automated robotic platform using laser and AI-vision for micro-propagation. | Produces high-precision, labeled image data for training computer vision models on plant morphology [8]. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | Precision gene-editing tool for functional genomics and trait improvement. | Creates defined genetic variants essential for validating AI-predicted gene-trait relationships [6] [8]. |

| LemnaTec Scanalyzer Platform | Automated, high-throughput phenotyping platform with multi-sensor imaging. | Primary source of large-scale, structured image datasets for developing and deploying DL phenotyping models [2]. |

Food security represents one of the most pressing global challenges, exacerbated by climate change, political instability, and economic fluctuations. According to recent data, over a quarter of a billion people experience acute food insecurity, a number that has dramatically increased since 2020 [9]. Simultaneously, climate change drives long-term disruptions in precipitation, temperature, and weather patterns, resulting in prolonged droughts, intense rainfall, storms, and rising sea levels that collectively hinder food production and distribution [9]. Within this context, data science emerges as a transformative discipline that enables researchers to develop innovative solutions by bridging plant physiology, advanced computing, and agricultural practice.

This technical guide examines how data science methodologies are being deployed to enhance crop resilience, optimize agricultural productivity, and ultimately strengthen global food systems. By leveraging advanced algorithms, machine learning techniques, and multimodal data analytics, researchers can now address challenges at the intersection of plant biology and climate variability with unprecedented precision [9]. The integration of these computational approaches with fundamental plant physiology research creates powerful frameworks for understanding and improving the genotype-to-phenotype relationship in crops, enabling the development of varieties better suited to withstand environmental stresses while maintaining yield and nutritional quality [10].

Quantitative Foundations: Data Science Applications in Plant Research

The application of data science in plant research spans multiple scales, from molecular analysis to field-level phenotyping. The table below summarizes key quantitative applications and their impacts on food security and climate resilience.

Table 1: Data Science Applications in Plant Research for Food Security and Climate Resilience

| Application Area | Data Science Methods | Key Metrics & Impact | Implementation Scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Phenotyping | Computer Vision, CNN, U-Net, LiDAR, Transformer models [11] [12] | Automated trait measurement (leaf count, size, disease severity); Temporal growth pattern analysis [12] | Laboratory to field-scale |

| Predictive Modeling for Yield & Stress | LSTM, GRU, Random Forest, SVM, CNN-LSTM hybrids [9] | Climate trend forecasting; Yield prediction under varying conditions [9] | Regional to global |

| Genotype-to-Phenotype Linking | Multimodal deep learning, Bioinformatics pipelines, Variant analysis [11] | Identification of molecular markers for climate-resilient crops [11] | Molecular to organism level |

| Resource Optimization | Time Series Forecasting (ARIMA), ANN, Clustering Techniques [9] | Optimization of irrigation, nutrient management; Reduction of resource waste [9] | Field to farm system |

The quantitative foundation of these applications relies on diverse data streams including imaging from drones and ground-based sensors, hyperspectral data, genomic sequences, and environmental sensor readings [11] [12]. The integration of these multimodal datasets enables researchers to move beyond traditional linear models to capture complex, non-linear relationships between genotype, environment, and phenotypic expression. For instance, while traditional ARIMA models have been used for short-term forecasting, hybrid approaches combining them with Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) have demonstrated a 96% reduction in prediction errors for agricultural datasets [9].

Experimental Protocols in Plant Phenotyping and Data Science

Protocol: UAV-Based High-Throughput Phenotyping for Stress Resilience

Objective: To quantitatively assess crop stress responses and structural traits under field conditions using remote sensing and deep learning analytics [11].

Materials and Equipment:

- Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV/drone) equipped with multispectral or hyperspectral sensors and LiDAR capability [11]

- Ground control points for spatial calibration

- High-performance computing infrastructure with GPU acceleration

- Field plots with experimental genetic varieties or treatment conditions

Methodology:

- Experimental Design: Establish field trials with randomized complete block design, incorporating different genotypes, treatment conditions (e.g., water deficit, nutrient variation), and replication appropriate for statistical power.

- Data Acquisition:

- Conduct regular UAV flights (e.g., weekly or bi-weekly) throughout growing season at ultralow-altitude (≤30m) for high spatial resolution [11]

- Capture synchronized multispectral imagery and LiDAR data at consistent times of day to minimize environmental variation

- Record precise GPS coordinates and meteorological data (temperature, humidity, solar radiation) during each flight

- Data Processing:

- Reconstruct 3D canopy architecture using structure-from-motion algorithms from LiDAR data [11]

- Extract vegetative indices (e.g., NDVI, PRI) from multispectral imagery

- Implement orthomosaic stitching and georeferencing for spatial consistency

- Trait Extraction Using Deep Learning:

- Apply optimized instance segmentation models (e.g., Mask R-CNN, U-Net variants) for individual plant detection and organ-level segmentation [11] [12]

- Quantify static traits (plant height, canopy cover, leaf area) and dynamic traits (growth rates, flowering dynamics) from temporal image series

- Utilize biologically-constrained optimization to ensure extracted traits maintain physiological relevance [12]

- Statistical Analysis and Genetic Mapping:

- Perform genome-wide association studies (GWAS) linking extracted phenotypic traits to genetic markers

- Identify quantitative trait loci (QTL) associated with stress resilience and yield stability

Protocol: Multimodal Data Integration for Predictive Modeling

Objective: To develop predictive models of crop performance under climate stress by integrating heterogeneous data sources [11] [9].

Materials and Equipment:

- High-performance computing cluster (CPU/GPU resources)

- Multimodal datasets (genomic, phenotypic, environmental)

- Data management platform (e.g., CropSight) for IoT-based data handling [11]

Methodology:

- Data Curation and Preprocessing:

- Compile genomic data (SNP markers, whole-genome sequences), phenomic data (from Protocol 3.1), and environmental data (soil metrics, weather records)

- Implement quality control pipelines to address missing data, outliers, and technical artifacts

- Normalize datasets to account for different scales and distributions

- Feature Engineering:

- Extract meaningful features from raw sensor data using convolutional autoencoders

- Calculate temporal features capturing growth dynamics from time-series phenotyping data

- Derive environmental covariates representing stress periods and optimal growth conditions

- Model Development and Training:

- Architect hybrid deep learning models (e.g., CNN-LSTM) capable of processing both spatial (images) and temporal (growth patterns) data [9]

- Incorporate biological constraints into model architecture to enhance interpretability and physiological relevance [12]

- Implement transfer learning approaches to leverage pre-trained models when labeled data is limited

- Utilize semi-supervised learning techniques to maximize use of available datasets

- Model Validation and Deployment:

- Validate model performance using k-fold cross-validation with independent test sets

- Assess generalizability across environments and growing seasons

- Deploy optimized models through cloud-based platforms or edge computing devices for real-time predictions

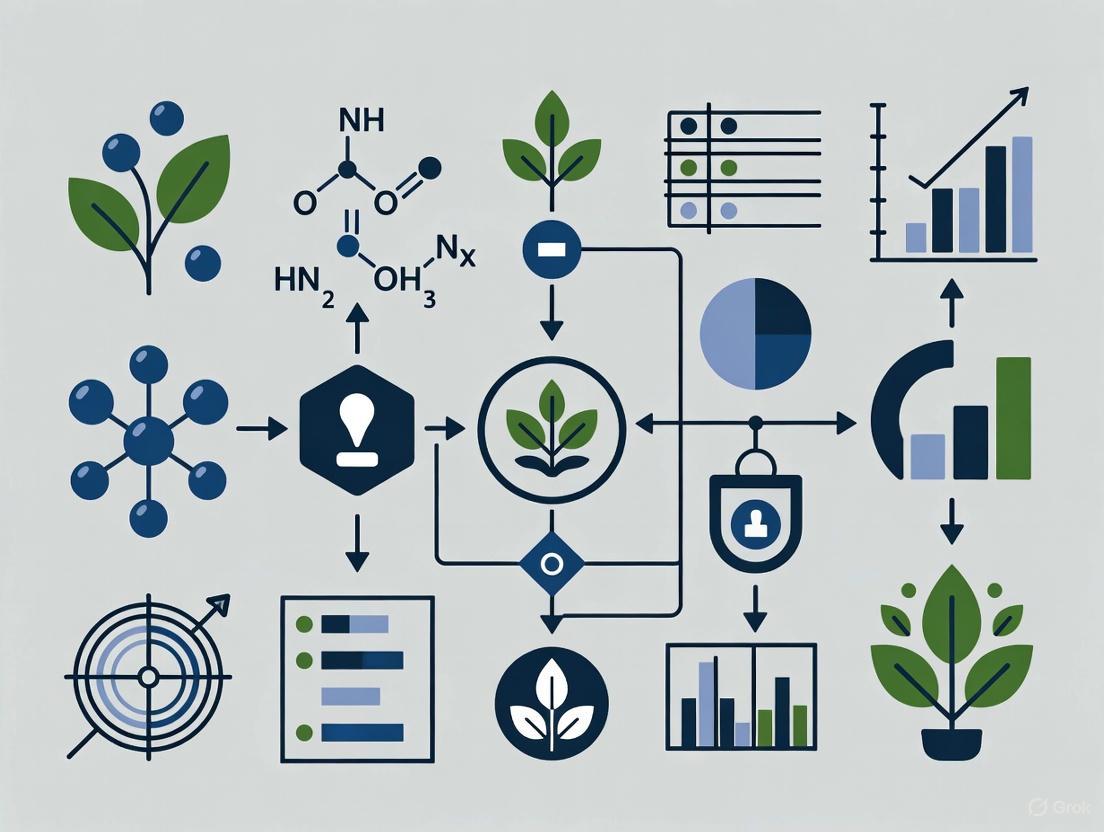

Visualization of Research Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate key experimental and computational workflows in plant phenotyping and data science applications.

Plant Phenotyping and Data Analysis Workflow

Genotype-to-Phenotype Pipeline

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Tools and Technologies for Plant Data Science

| Tool Category | Specific Technologies/Platforms | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Sensing & Imaging | UAVs with multispectral/hyperspectral sensors, LiDAR, IoT soil sensors [11] | Captures spatial and temporal data on plant growth, health, and environmental conditions at multiple scales |

| Data Management | CropSight, CropQuant-3D, AirMeasurer [11] | Manages high-volume phenotypic data, enables IoT-based crop management, and facilitates trait quantification |

| Analysis Software | Leaf-GP, SeedGerm, OrchardQuant-3D [11] | Provides automated, open-source solutions for measuring growth phenotypes, analyzing seed germination, and 3D orchard characterization |

| AI/ML Frameworks | CNN, RNN, LSTM, Transformer models, U-Net [11] [12] [9] | Enables image analysis, time-series forecasting, trait extraction, and predictive modeling from complex datasets |

| Computing Infrastructure | High-Performance Computing (HPC), GPU clusters, Cloud computing [11] | Provides computational power for training large models, processing massive datasets, and running complex simulations |

The integration of data science with plant physiology research represents a paradigm shift in how we approach food security and climate resilience. The methodologies and technologies outlined in this guide—from high-throughput phenotyping and multimodal data integration to advanced predictive modeling—provide researchers with powerful tools to accelerate crop improvement and develop sustainable agricultural practices. These approaches enable a more comprehensive understanding of the complex interactions between genotype, environment, and management practices that ultimately determine crop productivity and resilience.

As climate change continues to intensify global food security challenges, the role of data science in plant research becomes increasingly critical. Future advancements will likely focus on enhancing the interpretability of complex models, improving data sharing protocols through federated learning approaches, and developing more efficient algorithms that can leverage sparse data in resource-limited environments [13] [9]. By continuing to bridge the gap between computational innovation and biological insight, researchers can contribute significantly to building more resilient food systems capable of withstanding the climate challenges of the 21st century.

The expansion of genome sequencing technology has led to a rapid growth in plant genomic resources, providing a better understanding of plant genetic variation [14]. However, predicting phenotypic outcomes from genomic data remains a fundamental challenge in plant physiology research [15]. The relationship between genotype and phenotype involves complex, non-linear interactions influenced by environmental factors, gene regulation, and epigenetic modifications [1].

Artificial intelligence, particularly machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL), has emerged as a transformative approach for deciphering these complex relationships [1] [14]. Unlike traditional linear models, AI algorithms can autonomously extract features from high-dimensional datasets and represent their relationships at multiple levels of abstraction, enabling more accurate predictions of phenotypic traits from genetic and environmental data [14]. This technical guide examines current AI methodologies, experimental protocols, and research applications for genotype-to-phenotype prediction within the broader context of data science applications in plant physiology research.

AI Methodologies in Genotype-to-Phenotype Prediction

Machine Learning Approaches

Random Forest algorithms have demonstrated significant promise in genotype-to-phenotype prediction, particularly for handling high-dimensional genomic data and capturing non-additive genetic effects [14]. In predicting almond shelling fraction, Random Forest achieved a correlation of 0.727 ± 0.020, with R² = 0.511 ± 0.025 and RMSE = 7.746 ± 0.199, outperforming other methods [15]. The algorithm's ensemble approach of multiple decision trees reduces overfitting and improves generalization to new data.

Support Vector Machines (SVMs) represent another ML approach applied to plant genomics, particularly effective for classification tasks and handling high-dimensional SNP data [1]. SVMs work by finding the optimal hyperplane that separates different classes in a high-dimensional feature space, making them suitable for identifying genetic markers associated with specific phenotypic traits.

Bayesian Optimization has been successfully integrated with ML models to enhance prediction accuracy through sequential experimental design. In the EcoBOT automated phenotyping platform, Bayesian Optimization improved model accuracies relating copper concentrations to plant biomass by more than 30% through intelligent sequential experimentation [16].

Deep Learning Architectures

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have shown particular utility in analyzing plant imagery for phenotyping applications [1] [17]. These networks automatically extract relevant features from images, enabling high-throughput analysis of morphological traits. CNNs can process multispectral imagery from satellites, drones, or ground-based systems to monitor plant growth, detect stress symptoms, and quantify phenotypic traits [17].

Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) with multiple hidden layers can model complex non-linear relationships between genotypes and phenotypes [14]. When properly optimized, these networks have demonstrated superior performance compared to linear methods, particularly for traits with complex genetic architecture involving epistatic interactions [14].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of AI Models in Genotype-to-Phenotype Prediction

| Model Type | Application Context | Key Performance Metrics | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | Almond shelling fraction prediction | Correlation: 0.727 ± 0.020, R²: 0.511 ± 0.025, RMSE: 7.746 ± 0.199 [15] | Handles high-dimensional data, captures non-additive effects | Limited interpretability without XAI techniques |

| Deep Neural Networks | Multi-trait prediction in crops | Outperformed GBLUP in 6/9 datasets without G×E term [14] | Captures complex non-linear relationships | Requires large datasets, computationally intensive |

| Bayesian Optimization | EcoBOT biomass prediction | >30% improvement in accuracy [16] | Sequentially improves model through smart experimentation | Complex implementation, computationally expensive |

Explainable AI (XAI) for Biological Insight

A significant challenge in applying complex AI models to plant science is the "black box" problem, where model predictions lack biological interpretability [1] [15]. Explainable AI techniques address this limitation by elucidating the variables that have the most significant impact on predictive outcomes [15].

The SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) algorithm has been successfully applied to genotype-to-phenotype models, identifying specific genomic regions associated with phenotypic traits [15]. In almond research, SHAP values highlighted several genomic regions associated with shelling fraction, including one with the highest feature importance located in a gene potentially involved in seed development [15].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

Genotypic Data Processing: The standard workflow begins with quality control of SNP data, filtering for biallelic SNP loci with a minor allele frequency > 0.05 and call rate > 0.7 [15]. Linkage Disequilibrium (LD) pruning is then conducted using algorithms such as those implemented in PLINK v.1.90, which calculates pairwise R² for all marker pairs in sliding windows (typically size of 50 markers with increment of 5 markers), removing the first marker of pairs where R² < 0.5 [15]. The Variant Call Format (VCF) file undergoes encoding for ML applications: homozygous reference variants (0/0) are encoded as 0, heterozygous variants (0/1 and 1/0) as 1, and homozygous alternative variants (1/1) as 2 [15].

Phenotypic Data Collection: High-quality phenotypic data is essential for training accurate models. For almond shelling fraction, researchers used four-year data on kernel and fruit weight to calculate the average shelling fraction (ratio of kernel weight to total fruit weight) [15]. This longitudinal approach reduces environmental noise and provides more reliable trait measurements.

Image-Based Phenotyping: Automated platforms like EcoBOT capture thousands of plant images under controlled conditions [16]. The system analyzed over 6,500 root and shoot images to quantify plant responses to copper stress, demonstrating different sensitivity and response rates between root and shoot systems [16].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for AI-driven genotype-phenotype mapping

Feature Selection and Model Training

Dimensionality Reduction: The "curse of dimensionality" presents a significant challenge in genotype-to-phenotype prediction, where the number of SNP variables often vastly exceeds the number of plant samples [15]. Feature selection algorithms are nested within cross-validation procedures to prevent data leakage, where information from outside the training dataset inadvertently influences model development [15].

Cross-Validation: K-fold cross-validation (typically 10-fold) is employed to evaluate model performance robustly [15]. In this approach, the dataset is partitioned into k subsets, with each subset serving as the test set while the remaining k-1 subsets form the training set. This process is repeated k times, with performance metrics averaged across all iterations.

Multi-Modal Data Integration: Advanced ML approaches integrate diverse data types, including genomic variations, environmental parameters, and high-throughput phenotyping imagery [14] [17]. The integration of single-cell RNA sequencing with spatial transcriptomics, as demonstrated in the Arabidopsis thaliana atlas, provides unprecedented resolution of gene expression patterns across different cell types and developmental stages [18].

Advanced Research Applications

High-Resolution Genetic Atlas Construction

The creation of a foundational genetic atlas for Arabidopsis thaliana represents a significant advancement in plant genomics resources [18]. Researchers at the Salk Institute developed a comprehensive atlas spanning the entire Arabidopsis life cycle using single-cell and spatial transcriptomics, capturing the gene expression patterns of 400,000 cells across ten developmental stages [18].

This integrated approach paired single-cell RNA sequencing with spatial transcriptomics, enabling researchers to maintain the spatial context of cells and tissues throughout the sequencing process [18]. The resulting atlas has revealed a "surprisingly dynamic and complex cast of characters responsible for regulating plant development," including previously unknown genes involved in seedpod development [18].

Automated Phenotyping Platforms

The EcoBOT system exemplifies the integration of AI/ML with automated phenotyping capabilities [16]. This platform researches small model plants under axenic conditions, monitoring plant growth and health through automated imaging. The system maintains sterility while allowing precise control of environmental conditions and chemical treatments [16].

In practice, Brachypodium distachyon grown in the EcoBOT successfully responded to nutrient limitation and copper stress, with analysis of thousands of root and shoot images revealing distinct response patterns between root and shoot systems to copper exposure [16]. The integration of Bayesian Optimization enables the platform to sequentially improve model accuracies through intelligent experimental design.

Table 2: Quantitative Results from AI-Enhanced Plant Phenotyping Studies

| Study | Plant Species | Trait Analyzed | AI Methodology | Key Quantitative Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Almond Genomics [15] | Almond | Shelling fraction | Random Forest + SHAP | Correlation: 0.727 ± 0.020R²: 0.511 ± 0.025RMSE: 7.746 ± 0.199 |

| EcoBOT Platform [16] | Brachypodium distachyon | Biomass under copper stress | Bayesian Optimization + Image Analysis | >30% improvement in model accuracy6,500+ root and shoot images analyzed |

| Arabidopsis Atlas [18] | Arabidopsis thaliana | Gene expression across life cycle | Single-cell & Spatial Transcriptomics | 400,000 cells captured10 developmental stages mapped |

Explainable AI for Gene Discovery

The application of Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) techniques has bridged the gap between prediction accuracy and biological interpretability [15]. By employing SHAP values to explain Random Forest predictions, researchers can identify specific SNPs and genomic regions most strongly associated with phenotypic traits [15].

In the almond study, this approach highlighted several genomic regions associated with shelling fraction, with the highest feature importance located in a gene potentially involved in seed development [15]. This demonstrates how XAI transforms black-box models into biologically insightful tools for identifying candidate genes and understanding genetic architecture.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for AI-Enhanced Plant Genomics

| Research Tool | Function | Application in AI-Driven Plant Research |

|---|---|---|

| EcoBOT [16] | Automated plant growth and imaging platform | Provides high-throughput phenotyping data under controlled axenic conditions for AI/ML analysis |

| Single-cell RNA sequencing [18] | Resolution of gene expression at individual cell level | Generates high-resolution data for cell-type-specific gene expression patterns across development |

| Spatial Transcriptomics [18] | Gene expression analysis within tissue context | Maintains spatial organization of cells while capturing transcriptomic data for spatial ML models |

| TASSEL v.556 [15] | SNP data quality control and processing | Filters biallelic SNP loci based on MAF and call rate thresholds for reliable genotype data |

| PLINK v.1.90 [15] | Linkage Disequilibrium pruning | Reduces SNP dimensionality through LD-based filtering to address curse of dimensionality |

| SHAP Algorithm [15] | Model interpretability and feature importance | Identifies key genetic variants driving ML predictions for biological insight |

AI technologies are fundamentally transforming the approach to genotype-to-phenotype prediction in plant physiology research. Through machine learning, deep learning, and explainable AI techniques, researchers can now decipher complex biological relationships that were previously intractable with traditional linear models. The integration of automated phenotyping platforms, high-resolution genomic atlas data, and sophisticated AI algorithms creates a powerful framework for advancing plant breeding, biotechnology, and fundamental plant biology.

As these technologies continue to evolve, the plant research community will benefit from increasingly accurate predictions, deeper biological insights, and more efficient breeding strategies. The ongoing development of explainable AI approaches will be particularly crucial for ensuring that model predictions translate into actionable biological knowledge and practical breeding applications.

High-throughput plant phenomics has emerged as a transformative discipline that bridges the gap between plant genomics and physiological expression, generating massive datasets that enable unprecedented insights into plant growth, development, and stress responses. By leveraging automated imaging systems, advanced sensors, and computational analytics, researchers can now quantitatively measure complex plant traits at multiple biological scales—from cellular processes to whole-canopy architectures [19]. This data-rich approach has revolutionized traditional plant physiology by capturing dynamic responses to environmental cues with temporal resolution and statistical power previously unattainable through manual methods.

The integration of data science methodologies into plant phenomics has been particularly revolutionary, creating a synergistic relationship where large-scale phenotypic data informs physiological understanding while computational models generate testable hypotheses about underlying biological mechanisms [20]. This whitepaper examines the core technologies, analytical frameworks, and implementation strategies that define modern high-throughput plant phenomics, with specific emphasis on their applications in physiological research and agricultural innovation.

Imaging Technologies in Plant Phenomics

Advanced Imaging Modalities

High-throughput phenotyping platforms employ multiple imaging modalities to capture complementary aspects of plant physiology and morphology. Each modality reveals distinct physiological properties, enabling comprehensive profiling of plant status and function.

Table 1: Imaging Modalities in High-Throughput Plant Phenomics

| Imaging Modality | Physiological Parameters Measured | Technical Specifications | Applications in Plant Physiology |

|---|---|---|---|

| RGB Imaging | Morphological structure, color, growth dynamics | High-resolution cameras (≥20MP), controlled lighting | Biomass accumulation, architectural analysis, disease progression [20] |

| Multispectral Imaging | Vegetation indices (NDVI, PRI), photosynthetic efficiency | Multiple spectral bands (visible to NIR), narrow-band filters | Abiotic stress response, pathogen infection, nutrient status [19] |

| 3D Scanning/Photogrammetry | Canopy architecture, biomass volume, structural traits | Laser scanning, structured light, or multi-view reconstruction | Root system architecture, canopy light interception, growth modeling [21] |

| Thermal Imaging | Canopy temperature, stomatal conductance | High-sensitivity infrared sensors (7-14μm) | Water stress response, transpiration efficiency, stomatal regulation [19] |

Platforms like the PhenoLab exemplify the integration of these multimodal imaging approaches, combining robotic automation with multispectral imaging systems to enable simultaneous analysis of developmental processes, abiotic stress responses, and pathogen infections in both model and crop plants [19]. This integrated approach allows researchers to correlate morphological changes with physiological status, revealing functional relationships between plant form and physiological performance.

From Image Acquisition to Physiological Insights

The transformation of raw image data into physiologically meaningful information follows a structured computational pipeline that extracts quantifiable traits linked to plant function and performance.

This workflow demonstrates how raw sensor data undergoes progressive transformation through computational processing stages to yield insights about plant physiological status. For example, morphological features such as leaf area and stem thickness correlate with growth rates and biomass accumulation, while spectral features derived from multispectral imaging can reveal photosynthetic efficiency and nutrient deficiencies before visible symptoms appear [20]. The strength of this approach lies in connecting quantifiable image-derived traits with specific physiological processes, enabling non-destructive monitoring of plant function over time.

Deep Learning Frameworks for Phenotypic Data Extraction

Convolutional Neural Networks for Plant Image Analysis

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have become the cornerstone of modern plant image analysis, demonstrating remarkable performance in extracting meaningful physiological information from complex plant images. CNNs are a class of deep neural networks that use convolutional computations to automatically learn hierarchical features from raw images, eliminating the need for manual feature engineering [20]. This capability is particularly valuable in plant phenomics, where phenotypic expressions exhibit enormous diversity in color, shape, size, and structure across species, growth stages, and environmental conditions.

The effectiveness of CNNs in plant phenotyping has been rigorously validated across multiple applications. For instance, when evaluated on large public wood image databases, CNN models achieved 97.3% accuracy on the Brazilian wood image database (Universidade Federal do Paraná, UFPR) and 96.4% on the Xylarium Digital Database (XDD), significantly outperforming traditional feature engineering methods [20]. This superior performance stems from the ability of deep networks to learn discriminative features directly from data, capturing subtle patterns that may be overlooked in manual feature design.

3D Phenotyping Using Deep Learning

The application of deep learning to three-dimensional (3D) plant phenomics represents a significant advancement beyond traditional 2D approaches, enabling more accurate quantification of structural traits that are crucial for understanding plant physiology. Three-dimensional phenotyping provides comprehensive information about plant architecture, biomass distribution, and structural responses to environmental stimuli [21]. Deep learning has revolutionized 3D phenotyping through capabilities including 3D representation learning, classification, detection and tracking, semantic segmentation, instance segmentation, and 3D data generation.

The integration of 3D deep learning in plant phenomics faces several technical challenges, including the need for specialized 3D representations (e.g., point clouds, voxels, meshes), computational complexity of 3D data processing, and the scarcity of annotated 3D datasets. Recent approaches address these challenges through techniques such as multitask learning to share representations across related tasks, lightweight model architectures for efficient deployment, and self-supervised learning to reduce annotation requirements [21]. These advancements have enabled more accurate and efficient extraction of physiological traits from 3D plant data, such as leaf angle distribution that influences light interception efficiency, or root system architecture traits that determine resource acquisition capabilities.

Implementation Pipeline for Deep Learning in Phenomics

The successful implementation of deep learning for plant phenotyping requires a systematic approach to data management, model selection, and performance validation. The following protocol outlines key methodological considerations:

Data Acquisition and Preparation:

- Image Collection: Acquire images using high-resolution cameras, UAV photography, or 3D scanning systems under controlled lighting conditions where possible [20].

- Dataset Sizing: For binary classification tasks, collect 1,000-2,000 images per class; for multi-class classification, 500-1,000 images per class; for complex tasks like object detection, aim for ≥5,000 images per object of interest [20].

- Data Annotation: Utilize annotation tools (e.g., labelImg [22]) to generate ground truth data for supervised learning. This remains a labor-intensive process but is essential for model training.

Preprocessing and Augmentation:

- Image Standardization: Apply cropping, resizing, and color normalization to standardize input dimensions and appearance [20].

- Data Augmentation: Generate synthetic training examples through rotation, flipping, contrast adjustment, and other transformations to improve model robustness and prevent overfitting [20].

- Background Suppression: Implement techniques to remove complex backgrounds that may interfere with feature extraction.

Model Selection and Training:

- Architecture Choice: Select appropriate network architectures based on the specific phenotyping task (e.g., CNNs for image classification, YOLO variants for object detection, U-Net for segmentation).

- Transfer Learning: Leverage pre-trained models on large-scale datasets (e.g., ImageNet) to accelerate training and improve performance, especially with limited plant-specific data.

- Optimization: Utilize techniques such as the Ghost module and bi-directional Feature Pyramid Network (biFPN) to create more efficient models suitable for deployment in resource-constrained environments [22].

Validation and Deployment:

- Performance Metrics: Evaluate models using appropriate metrics (e.g., mean Average Precision for object detection, accuracy for classification) on held-out test sets.

- Physiological Validation: Correlate algorithm outputs with manually measured physiological parameters (e.g., high correlation between image-derived berry size and actual weight, R² > 0.93 [22]) to ensure biological relevance.

- Application Development: Package trained models into user-friendly applications (e.g., smartphone apps) to increase accessibility for researchers and breeders [22].

Case Study: High-Throughput Blueberry Phenotyping

Experimental Implementation

A comprehensive case study illustrating the practical application of high-throughput phenotyping involves the development of automated tools for blueberry count, weight, and size estimation using modified YOLOv5s architecture [22]. This implementation addresses the critical need for efficient measurement of berry traits that directly influence marketability and breeding decisions.

The research utilized two distinct computer vision pipelines to enable comparative performance analysis:

- Traditional Pipeline: Employed classical computer vision algorithms including Hough Transform, Watershed, and filtering techniques.

- Deep Learning Pipeline: Implemented YOLOv5 models with architectural enhancements using the Ghost module for computational efficiency and biFPN for improved feature fusion [22].

The study collected 198 RGB images of blueberries alongside manually measured berry count and average berry weight to serve as ground truth for model training and validation. This dataset exemplified the scale required for effective deep learning implementation in plant phenotyping.

Performance Results and Physiological Correlation

The YOLOv5-based model demonstrated exceptional performance in berry counting, miscounting only four berries out of 4,604 total berries across all 198 images, achieving a mean Average Precision of 92.3% averaged across Intersection-over-Union thresholds from 0.50 to 0.95 [22]. This high precision in detection directly translates to reliable data for physiological studies of fruit development and yield components.

Most significantly for physiological research, the image-derived average berry size measurements showed strong correlation with manually measured average berry weight (R² > 0.93), resulting in a mean absolute error of approximately 0.14 g (8.3%) [22]. This level of accuracy demonstrates that computer vision approaches can effectively replace labor-intensive manual measurements while providing additional spatial and temporal resolution for understanding fruit development patterns.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Deep Learning Models in Plant Phenotyping

| Model Architecture | Application Context | Key Performance Metrics | Physiological Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modified YOLOv5s (Ghost + biFPN) | Blueberry detection and sizing | 92.3% mAP, 0.14g mean absolute error in weight estimation | Fruit size, weight, yield components [22] |

| CNN Models | Wood species identification | 97.3% accuracy (UFPR database), 96.4% accuracy (XDD database) | Species-specific anatomical features [20] |

| 3D Deep Learning | Plant architecture analysis | Improved structural trait quantification vs. 2D approaches | Biomass volume, canopy structure, light interception [21] |

Data Management and Standardization Frameworks

FAIR Data Principles in Plant Phenomics

The massive data volumes generated by high-throughput phenotyping platforms necessitate robust data management strategies to ensure usability, reproducibility, and integration across studies. The FAIR data principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) provide a critical framework for managing plant phenomics data [23]. Implementation of these principles requires systematic attention to metadata standards, data organization, and storage infrastructures throughout the research lifecycle.

Specialized information systems have been developed to address the unique requirements of plant phenomics data. The Phenotyping Hybrid Information System (PHIS) offers a comprehensive solution for collecting, organizing, and sharing multi-domain phenotyping data [23]. PHIS architecture supports the integration of diverse data types including imaging data, environmental sensor readings, and genomic information, enabling researchers to explore complex relationships between genotypes, environments, and phenotypic outcomes.

Metadata Standards and Semantic Frameworks

Effective data sharing and integration in plant phenomics depends on consistent application of metadata standards and semantic frameworks. Workshops dedicated to data standards in plant phenotyping emphasize the importance of meta-information needs, multi-domain data concepts, and standardized terminologies [23]. These standards enable unambiguous interpretation of phenotypic measurements and experimental contexts, which is essential for comparative analyses across studies and meta-analyses that aggregate findings from multiple experiments.

The implementation of standardized data collection protocols ensures that phenotypic data generated in different laboratories or using different platforms can be meaningfully compared and integrated. This interoperability is particularly important for physiological studies seeking to identify consistent patterns of plant response across environments or genetic backgrounds.

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for High-Throughput Plant Phenomics

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| PhenoLab Platform | Automated, high-throughput phenotyping with robotic systems | Analysis of development, abiotic stress responses, and pathogen infection [19] |

| Multispectral Imaging Systems | Capture spectral signatures beyond visible spectrum | Quantifying vegetation indices, photosynthetic efficiency, stress markers [19] |

| OpenSILEX Python Tool | Data management and integration with PHIS | Creating experiments, importing data, implementing FAIR principles [23] |

| labelImg Annotation Tool | Manual image annotation for ground truth generation | Creating training datasets for supervised machine learning [22] |

| YOLOv5 Framework | Real-time object detection system | Fruit counting, size estimation, disease detection [22] |

| 3D Scanning Technologies | Capture plant architectural data | Root system architecture, canopy structure, biomass estimation [21] |

Future Perspectives and Challenges

Emerging Technologies and Methodological Innovations

The field of high-throughput plant phenomics continues to evolve rapidly, driven by technological advancements and computational innovations. Several promising directions are poised to enhance the physiological insights derived from phenotypic data:

Benchmark Dataset Construction: Current limitations in annotated training data are being addressed through synthetic dataset generation using generative artificial intelligence and unsupervised or weakly supervised learning approaches [21]. These methods will enable more robust model training while reducing the annotation burden.

Advanced Modeling Techniques: Future developments will leverage multitask learning to simultaneously predict multiple physiological parameters, lightweight model architectures for field deployment, and self-supervised learning to extract meaningful representations without extensive labeling [21]. These approaches will increase the efficiency and applicability of phenotyping systems across diverse environments and species.

Multimodal Data Integration: The integration of phenotypic data with other data types, including genomic, transcriptomic, and environmental information, will enable more comprehensive understanding of physiological processes [21]. Large Language Models (LLMs) specialized for biological data, such as the Agronomic Nucleotide Transformer (AgroNT), show particular promise for uncovering novel gene-stress associations and regulatory patterns that connect genetic variation to phenotypic expression [20].

Implementation Challenges and Solutions

Despite significant progress, several challenges remain in the widespread adoption of high-throughput phenotyping for physiological research:

Data Quality and Annotation: The lack of high-quality annotated data continues to hinder the development of accurate models, particularly for rare traits or species. Potential solutions include collaborative annotation initiatives, transfer learning from related domains, and semi-supervised approaches that leverage both labeled and unlabeled data [20].

Computational Resources: The processing and storage requirements for high-dimensional phenotyping data can be prohibitive, especially for 3D and temporal analyses. Cloud computing resources, efficient compression algorithms, and optimized model architectures will help mitigate these constraints.

Physiological Interpretation: Translating phenotypic measurements into meaningful physiological understanding remains challenging. This requires closer collaboration between computer scientists and plant physiologists to ensure that extracted features correspond to biologically relevant traits and processes.

As these challenges are addressed, high-throughput plant phenomics will increasingly become an integral component of plant physiological research, enabling unprecedented insights into the functional responses of plants to their environments and genetic makeup. The continued integration of data science approaches with plant biology will ultimately enhance our ability to understand and manipulate plant physiology for improved agricultural sustainability and productivity.

In modern plant physiology research, a holistic understanding of plant systems requires the integration of diverse, high-dimensional data. The convergence of genomics, phenomics, environmental monitoring, and metabolomics is transforming plant science from a discipline focused on individual components to one that can address system-level complexity [24] [25]. This integrated approach is particularly crucial for unraveling the intricate relationships between genotype, phenotype, and environment—a fundamental challenge in plant biology with significant implications for crop improvement, climate resilience, and sustainable agriculture.

The era of plant data science has emerged through technological revolutions across multiple scientific domains. Breakthroughs in high-throughput sequencing have democratized access to genomic data [26], while advances in sensor technology and computer vision have enabled large-scale phenotyping [27]. Simultaneously, sophisticated analytical platforms now allow comprehensive profiling of metabolic networks [28] [29], and innovative monitoring systems facilitate detailed recording of environmental parameters and plant electrophysiological responses [30]. This technical guide provides a comprehensive overview of these core data types, their sources, methodologies for integration, and applications within plant physiology research.

Core Data Types in Plant Physiology

Genomic Data

Genomic data forms the foundational blueprint of plant biology, encompassing the complete genetic information encoded in DNA. This data type includes sequences of nuclear and organellar genomes, gene annotations, regulatory elements, and genetic variations such as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and structural variants. Recent advances have dramatically expanded the scope and accessibility of plant genomic data, with approximately 1,500 plant species sequenced as of 2024 [26].

Table 1: Genomic Data Types and Technologies

| Data Category | Specific Data Types | Key Technologies | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclear Genome | DNA sequence, gene models, regulatory regions | Long-read sequencing (PacBio, Nanopore), short-read sequencing (Illumina), Hi-C | Genome assembly, gene discovery, evolutionary studies |

| Organellar Genomes | Chloroplast DNA, mitochondrial DNA | Long-read sequencing, PCR-based methods | Phylogenetics, population genetics, evolutionary studies |

| Epigenomic Data | DNA methylation patterns, histone modifications | Bisulfite sequencing, ChIP-seq | Gene regulation studies, environmental response analysis |

| Genetic Variation | SNPs, insertions/deletions, structural variants | Whole-genome resequencing, GWAS panels | Trait mapping, marker-assisted selection, population genetics |

The emergence of high-quality chromosome-scale assemblies has been particularly transformative. For example, the chromosome-scale genome assembly of Chouardia litardierei has enabled investigations into genomic diversity linked to ecological adaptation across different ecotypes [26]. Beyond protein-coding genes, genomic "dark matter"—including promoters, microRNAs, and transposable elements—represents a rich frontier for discovery, with studies now characterizing tissue-specific promoters like the AhN8DT-2 promoter from peanuts for genetic engineering applications [26].

Phenomic Data

Phenomic data encompasses the comprehensive measurement of plant physical and biochemical traits across temporal and spatial scales. Modern phenomics leverages automated, high-throughput platforms to capture trait data at unprecedented scale and resolution, moving beyond traditional manual measurements [27].

Table 2: Phenomic Data Acquisition Technologies

| Phenotyping Approach | Measured Traits | Sensing Technologies | Scale and Throughput |

|---|---|---|---|

| Imaging-Based Phenotyping | Plant architecture, biomass, color, growth rates | RGB, hyperspectral, fluorescence, thermal cameras | Laboratory to field scale; moderate to high throughput |

| 3D Phenotyping | Canopy structure, root architecture | LiDAR, laser scanning, X-ray CT, MRI | Primarily controlled environments; moderate throughput |

| Field-Based Phenomics | Crop vigor, stress responses, yield components | UAVs, tractor-mounted sensors, satellites | Large scale; very high throughput |

| Plant Wearable Sensors | Sap flow, electrophysiology, microclimate | Electrodes, temperature/humidity sensors, solar panels | Continuous monitoring; single plant resolution |

Modern phenomics platforms utilize multi-modal sensors to capture reflective, emitted, and fluorescence signals from plant organs at different spatial and temporal resolutions [27]. These technologies enable the correlation of phenotypic traits with genetic markers and environmental conditions. For instance, plant-wearable devices like the PhytoNode can continuously record electrophysiological activity in species such as Hedera helix (ivy) under real-world conditions, capturing plant responses to environmental stimuli [30].

Environmental Data

Environmental data quantifies the abiotic and biotic conditions that plants experience throughout their life cycle. This data type is essential for understanding genotype-by-environment interactions and phenotypic plasticity. The "life-course approach"—originally developed in human epidemiology—has been adapted for plant studies to elucidate how environmental exposures at different developmental stages cumulatively affect later outcomes and agronomic traits [24].

Environmental parameters critical for plant studies include:

- Climate factors: Air temperature, relative humidity, precipitation, solar irradiance

- Soil conditions: Soil moisture, temperature, nutrient availability, pH

- Atmospheric conditions: CO₂ concentration, ozone levels, wind speed and direction

- Biotic environment: Pest pressure, disease prevalence, plant competition

Advanced monitoring systems deploy networks of sensors to capture these parameters at high temporal resolution. In one study, environmental parameters including wind speed, air temperature, relative humidity, solar irradiance, precipitation, and dew point temperature were recorded at a sampling frequency of 0.1 Hz alongside plant electrophysiological measurements [30].

Metabolomic Data

Metabolomic data provides a comprehensive profile of the small molecule metabolites within plant tissues, offering a direct readout of physiological status and biochemical activity. Plants are estimated to produce over 200,000 metabolites, with individual species containing between 7,000-15,000 different compounds [29]. These metabolites are crucial executors of gene functions and key mediators of plant-environment interactions.

Table 3: Metabolomic Analytical Platforms and Applications

| Analytical Platform | Metabolite Coverage | Key Strengths | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| GC-MS | Primary metabolites (sugars, organic acids, amino acids), volatile compounds | High separation efficiency, reproducible fragmentation patterns | Metabolic profiling, flux analysis, volatile compound studies |

| LC-MS | Secondary metabolites, lipids, non-volatile compounds | Broad coverage, high sensitivity, minimal sample derivation | Phytochemical analysis, stress response studies, bioactivity screening |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Diverse compound classes with detectable protons | Quantitative, non-destructive, minimal sample preparation | Structural elucidation, metabolic fingerprinting, in vivo tracking |

| Mass Spectrometry Imaging | Spatial distribution of metabolites | Preservation of spatial context, localization of compounds | Tissue-specific metabolism, transport studies, defense responses |

Mass spectrometry has emerged as the cornerstone technology for plant metabolomics due to its high sensitivity, throughput, and accuracy [29]. Spatial metabolomics techniques, such as mass spectrometry imaging, further enable precise localization of metabolite distribution within plant tissues, providing insights into compartmentalization of metabolic processes [29]. Metabolites function not only as end products of metabolic pathways but also as important signaling molecules; for example, abscisic acid (ABA) regulates multiple metabolic pathways to enhance plant resilience to environmental stresses [29].

Methodologies for Data Integration and Analysis

Multi-Omics Integration Approaches

The integration of heterogeneous datasets from multiple omics domains presents both technical and conceptual challenges. Successful multi-omics integration requires specialized computational strategies that can handle differences in data scale, dimensionality, and biological meaning. Several approaches have emerged as particularly valuable for plant studies:

Genome-scale metabolic network reconstruction creates functional cellular network structures based on gene annotation, making pathways accessible to computational analysis [25]. These networks facilitate mechanistic descriptions of genotype-phenotype relationships and enable constraint-based analysis methods. For example, a genome-scale metabolic model for maize leaf comprising over 8,500 reactions was used in combination with transcriptomic and proteomic data to investigate nitrogen assimilation, successfully reproducing experimentally determined metabolomic data with high accuracy [25].

Time-series multi-omics analysis captures the dynamics of plant responses to environmental changes and developmental transitions. This approach has revealed that longer physiological responses often depend on genetic variations, plant age, and developmental stage [24]. The life-course approach employs concepts of timing, trajectory, transition, and turning point to identify causal relationships between factors and their impacts on plant outcomes over time [24].

Machine learning and automated workflows are increasingly employed to handle the complexity of multi-omics data. Automated Machine Learning (AutoML) approaches have demonstrated particular utility, outperforming manually tuned models in classifying plant electrophysiological responses to environmental conditions with F1-scores of up to 95% in binary classification tasks [30]. These methods automate the selection of preprocessing steps, feature extraction, and model hyperparameter optimization.

Workflow for Plant Electrophysiology and Environmental Response Monitoring

The following workflow illustrates an integrated approach for monitoring plant electrophysiological responses to environmental conditions:

Experimental Protocol: Plant Electrophysiology Monitoring

Sensor Deployment: Install plant-wearable devices (e.g., PhytoNode) on selected plant species (e.g., Hedera helix). Insert one silver-coated electrode at the lower stem just above soil level and another electrode either in the same stem or in a leaf petiole, maintaining a distance of 30-60 cm between electrodes [30].

Data Acquisition: Record electrical potential measurements at approximately 200 Hz sampling frequency. Simultaneously collect environmental data including wind speed, air temperature, relative humidity, solar irradiance, precipitation, and dew point temperature at 0.1 Hz sampling frequency [30].

Preprocessing: Downsample the electrophysiological time series to 1 Hz using a mean filter over 1-second intervals. Exclude days with less than 80% data coverage. Apply z-score normalization to the time series using the formula $z = \frac{x - \mu}{\sigma}$ where $x$ is the raw sample, $\mu$ is the time series mean, and $\sigma$ is the standard deviation [30].

Feature Extraction: Segment the preprocessed data into time windows corresponding to specific environmental conditions. Extract statistical features (e.g., mean, variance, extreme values, percentiles) from each time window for subsequent analysis [30].

Machine Learning: Apply Automated Machine Learning (AutoML) frameworks to automatically compose and parameterize ML algorithms. Compare results with manually crafted ML approaches. Implement feature selection to identify the most informative statistical features for classification tasks [30].

Validation: Evaluate model performance using metrics such as F1-score, with reported performance reaching up to 95% in binary classification tasks for environmental condition identification [30].

Workflow for Multi-Omics Studies in Plant Biology

The following diagram outlines a generalized workflow for integrated multi-omics studies in plant biology:

Experimental Protocol: Multi-Omics Data Integration

Experimental Design: Implement a life-course approach that captures molecular and phenotypic data across multiple developmental stages and environmental conditions [24]. For Arabidopsis studies, collect data across 10 developmental stages from seed to flowering adulthood [31].

Sample Collection: Harvest plant materials in biological replicates with careful documentation of growth conditions, developmental stage, and harvesting time. Immediately flash-freeze samples in liquid nitrogen for molecular analyses to preserve metabolic profiles.

Multi-Omics Data Generation:

- Genomics: Perform whole-genome sequencing using long-read technologies (PacBio, Nanopore) for assembly and short-read technologies (Illumina) for variant calling [26].

- Transcriptomics: Conduct RNA sequencing with single-cell or spatial resolution where appropriate. Single-cell RNA sequencing enables comprehensive cataloging of cell types and developmental states [31].

- Metabolomics: Employ LC-MS and GC-MS platforms for comprehensive metabolite profiling. Utilize mass spectrometry imaging for spatial localization of metabolites [29].

- Phenomics: Implement high-throughput phenotyping platforms with multi-modal sensors (RGB, hyperspectral, fluorescence) to capture plant growth and trait dynamics [27].

Data Integration: Combine heterogeneous datasets using statistical correlation methods, pathway mapping, and network analysis. Leverage genome-scale metabolic networks to provide biochemical context for omics data [25].

Computational Modeling: Develop constraint-based models of metabolism that integrate transcriptomic and proteomic data to improve flux predictions [25]. Apply machine learning algorithms to identify patterns and relationships across omics layers.

Validation: Conduct functional validation through genetic transformation (overexpression, gene silencing) and biochemical assays. For example, validate gene functions through overexpression in yeast or soybean hairy roots, as demonstrated for the sulfate transporter gene GmSULTR3;1a [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Plant Data Science

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Application | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Technologies | PacBio SMRT, Oxford Nanopore, Illumina NovaSeq | Genome assembly, variant calling, transcriptome profiling | Chromosome-scale genome assembly [26], single-cell RNA sequencing [31] |

| Mass Spectrometry Platforms | GC-MS, LC-MS, Orbitrap, MALDI-TOF | Metabolite identification and quantification, lipidomics | Plant metabolite profiling [29], spatial metabolomics [29] |

| Phenotyping Systems | RGB cameras, hyperspectral sensors, LiDAR, UAVs | High-throughput trait measurement, growth monitoring | 3D phenotyping, field-based phenomics [27] |

| Plant Wearable Sensors | PhytoNode, silver-coated electrodes, solar panels | Continuous electrophysiological monitoring | Real-time plant response tracking [30] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Genome assemblers, AutoML frameworks, metabolic network reconstructions | Data processing, integration, and modeling | Automated classification of plant signals [30], multi-omics integration [25] |

| Functional Validation Tools | CRISPR-Cas9, RNAi vectors, yeast expression systems | Gene function characterization, genetic engineering | Sulfate transporter function validation [26], promoter analysis [26] |

The integration of genomic, phenomic, environmental, and metabolomic data represents a paradigm shift in plant physiology research, enabling a systems-level understanding of plant function and adaptation. While technical challenges remain in data management, integration methodologies, and model interpretation, the continued advancement of technologies and analytical frameworks promises to further enhance our ability to decode the complex relationships between plant genotype, phenotype, and environment. These approaches are not only transforming basic plant science but also accelerating the development of improved crop varieties with enhanced yield, stress resilience, and nutritional quality—critical goals for ensuring food security in the face of global climate change.

Machine Learning Workflows for Plant Physiological Analysis

The application of machine learning (ML) in plant physiology research represents a paradigm shift in how researchers analyze complex biological systems. These computational approaches enable the modeling of non-linear relationships between genetic, environmental, and physiological factors that traditional statistical methods often struggle to capture [32]. In plant-based research, where experimental conditions are inherently multivariate and dynamic, selecting the appropriate ML algorithm is crucial for generating reliable, interpretable, and actionable insights. This guide provides a comprehensive framework for selecting and implementing four prominent ML algorithms—Random Forests, Support Vector Machines (SVMs), Neural Networks, and XGBoost—specifically for plant data analysis within physiological and pharmacological contexts.

The unique challenges of plant data, including high dimensionality, non-linear genotype-by-environment interactions, and often limited sample sizes, necessitate careful algorithm selection [32] [33]. This guide addresses these challenges by providing structured comparisons, detailed experimental protocols, and visualization of algorithmic workflows to empower researchers in making informed decisions for their specific research contexts.

Algorithm Comparative Analysis

Fundamental Characteristics and Plant Science Applications

Table 1: Core Algorithm Characteristics and Applications in Plant Research

| Algorithm | Core Mechanism | Strengths | Ideal Plant Science Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest (RF) | Ensemble of independent decision trees using bagging | Robust to overfitting, handles high-dimensional data well, provides feature importance scores [34] [32] | Predicting morphological traits [32], estimating forest growing stock [35], phenotypic analysis |

| XGBoost | Sequential ensemble building trees to correct previous errors | High predictive accuracy, handles class imbalance, built-in regularization [34] [36] [37] | Disease severity classification [37], yield prediction with imbalanced data, high-precision phenotyping |

| Support Vector Machines (SVM) | Finds optimal hyperplane to separate data classes | Effective in high-dimensional spaces, memory efficient, versatile via kernel functions [38] [33] | Plant disease detection from images [33], spectral data classification, small to medium datasets |

| Neural Networks (NN) | Network of interconnected layers that learn hierarchical representations | Models complex non-linear relationships, handles diverse input types, state-of-the-art for image/data fusion [32] [33] | Multimodal data fusion [33], hyperspectral image analysis [33], complex trait prediction |

Performance Metrics and Practical Considerations

Table 2: Performance Comparison and Implementation Considerations

| Algorithm | Reported Performance (R²/Accuracy) | Training Speed | Hyperparameter Tuning Complexity | Interpretability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | R²=0.84-0.875 (morphological traits) [32] [38], 0.75 (livestock weight prediction) [39] | Fast (parallelizable) [34] | Low (few parameters) [34] | Medium (feature importance available) [34] |

| XGBoost | Accuracy=0.9186 (disease severity) [37], limited error=0.07 (cotton yield) [38] | Fast (optimized implementation) [34] [36] | High (many parameters) [34] [36] | Medium (feature importance available) |

| SVM | Accuracy=0.94 (disease outbreaks) [38], 97.54% (tomato grading with CNN) [38] | Slower with large datasets [33] | Medium (kernel-specific parameters) | Low (black-box nature) |

| Neural Networks | R²=0.80 (morphological traits with MLP) [32], 95-99% (lab image analysis) [33] | Slower (requires more data) [33] | High (architecture and parameters) [33] | Low (black-box nature) [33] |

Algorithm Selection Framework

Decision Framework for Plant Research Applications

Selecting the optimal algorithm depends on multiple factors specific to plant research contexts. For high-dimensional morphological trait prediction with numerous input features (e.g., genotype, planting date, environmental parameters), Random Forest demonstrates superior performance, achieving R² values of 0.84 in predicting roselle morphological traits [32]. When working with imbalanced datasets common in plant disease detection, where healthy samples often outnumber diseased ones, XGBoost's built-in handling of class imbalance makes it preferable, as demonstrated by its F1 scores exceeding 0.9186 in sugarcane disease severity classification [37].

For image-based plant disease detection, the optimal algorithm selection becomes more nuanced. While Neural Networks (particularly CNNs and Transformers) achieve 95-99% accuracy in controlled laboratory conditions, their performance drops to 70-85% in field deployment [33]. In resource-constrained scenarios or when working with smaller image datasets, SVM combined with traditional feature extraction can provide more robust performance with lower computational requirements [33].

When model interpretability is crucial for biological insight, such as understanding which morphological traits most influence yield, Random Forest provides feature importance scores that offer transparency into decision processes [34] [32]. For large-scale prediction tasks with structured tabular data, XGBoost often achieves slightly superior accuracy compared to Random Forest, though with increased tuning complexity [34] [35].

Experimental Protocol for Algorithm Validation in Plant Studies

Implementing a standardized experimental protocol ensures comparable algorithm performance assessment:

1. Data Preprocessing Protocol:

- For plant morphological data: Apply z-score standardization to output variables and one-hot encoding to categorical features like genotype and treatment groups [32]

- For spectral/imaging data: Apply min-max normalization to pixel values or spectral indices [37]

- Conduct outlier detection and removal using standard deviation methods (e.g., excluding values beyond Mean ± 2*Standard Deviation) [39]

2. Dataset Partitioning:

- Implement K-fold cross-validation (typically 5-fold) to mitigate overfitting [39]

- Maintain consistent class distribution across splits for imbalanced plant disease data

- For temporal plant data, use forward-chaining validation to respect chronological order

3. Performance Validation: