Benchmarking scRNA-seq Analysis Pipelines: A Comprehensive Guide to Best Practices and Tool Selection

The rapid evolution of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has created a complex landscape of over 1,400 computational tools, making pipeline selection challenging for researchers and drug development professionals.

Benchmarking scRNA-seq Analysis Pipelines: A Comprehensive Guide to Best Practices and Tool Selection

Abstract

The rapid evolution of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has created a complex landscape of over 1,400 computational tools, making pipeline selection challenging for researchers and drug development professionals. This article synthesizes findings from major benchmarking studies to provide a definitive guide for constructing robust scRNA-seq analysis workflows. We cover foundational principles, methodological comparisons of best-performing tools for key steps like normalization and batch correction, strategies for troubleshooting and optimization, and frameworks for the rigorous validation of analytical results. By outlining evidence-based best practices, this guide empowers scientists to navigate methodological choices confidently, avoid common pitfalls, and derive biologically accurate insights from their single-cell data, ultimately accelerating discovery in biomedicine.

Navigating the scRNA-seq Landscape: From Experimental Protocols to Data Generation

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized transcriptomic studies by enabling the investigation of cellular heterogeneity, rare cell populations, and developmental trajectories at unprecedented resolution. The fundamental division in scRNA-seq methodologies lies between full-length transcript protocols and 3'-end counting protocols, each with distinct advantages, limitations, and applications. Full-length methods such as Smart-Seq2 and FLASH-seq capture complete transcript information, enabling isoform analysis and variant detection, while 3'-end methods like Drop-Seq and inDrop utilize unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) for quantitative gene expression profiling at scale. This comprehensive review synthesizes current evidence to objectively compare these technological approaches, providing researchers with practical guidance for selecting appropriate methodologies based on specific research objectives, sample types, and analytical requirements.

The evolution from bulk RNA sequencing to single-cell approaches represents a paradigm shift in transcriptomics, moving from population-averaged measurements to cell-specific resolution [1] [2]. While bulk RNA-seq provides an average gene expression profile across thousands to millions of cells, scRNA-seq captures the transcriptional landscape of individual cells, revealing heterogeneity that was previously obscured [3] [2]. This technological advancement has been instrumental in discovering novel cell types, characterizing tumor microenvironments, reconstructing developmental lineages, and understanding disease mechanisms at cellular resolution.

The scRNA-seq workflow encompasses several critical steps: single-cell isolation, cell lysis, reverse transcription, cDNA amplification, and library preparation [1]. Technical variations at each step have given rise to diverse protocols, which can be broadly categorized based on their transcript coverage. Full-length protocols capture nearly complete transcript sequences, while 3'-end protocols focus primarily on the 3' termini of transcripts [1]. This fundamental distinction governs their applications, with full-length methods enabling isoform-level analysis and 3'-end methods excelling in high-throughput quantitative profiling.

Technical Specifications and Methodological Comparison

Full-Length Transcript Protocols

Full-length scRNA-seq methods are characterized by their comprehensive coverage across the entire transcript, enabling detailed molecular characterization beyond simple gene counting. These protocols typically employ polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for amplification and are well-suited for plate-based platforms where sensitivity and transcript completeness are prioritized over throughput [1].

Smart-Seq2 has established itself as a gold standard among full-length protocols, offering enhanced sensitivity for detecting low-abundance transcripts and generating full-length cDNA [1] [4]. Its high detection sensitivity makes it particularly valuable for applications requiring comprehensive transcriptome coverage, such as isoform usage analysis, allelic expression detection, and identification of RNA editing events. However, Smart-Seq2 does not incorporate UMIs, which can limit precise transcript quantification.

FLASH-seq (FS) represents a recent innovation in full-length scRNA-seq, offering reduced hands-on time (approximately 4.5 hours) and increased sensitivity compared to previous methods [4]. By combining reverse transcription and cDNA preamplification, replacing reverse transcriptase with the more processive Superscript IV, and modifying template-switching oligonucleotides, FLASH-seq detects more genes per cell while maintaining full-length coverage. The method can be miniaturized to 5μl reaction volumes, reducing resource consumption, and can be adapted to include UMIs (FS-UMI) for improved quantification accuracy while minimizing strand-invasion artifacts that can affect other protocols [4].

MATQ-Seq offers another full-length approach with increased accuracy in quantifying transcripts and efficient detection of transcript variants [1]. Comparative studies indicate that MATQ-Seq outperforms even Smart-Seq2 in detecting low-abundance genes, though it requires specialized expertise and resources [1].

3'-End Counting Protocols

3'-end scRNA-seq protocols focus sequencing efforts on the 3' ends of transcripts, typically incorporating UMIs for precise molecular counting. These methods are predominantly droplet-based, enabling high-throughput processing of thousands to millions of cells simultaneously at a lower cost per cell [1] [3].

Drop-Seq utilizes droplet microfluidics to encapsulate individual cells with barcoded beads, enabling massively parallel processing at low cost [1]. The method sequences only the 3' ends of transcripts but incorporates UMIs for accurate transcript counting. Its high throughput makes it ideal for large-scale atlas projects and detecting diverse cell subpopulations in complex tissues.

inDrop employs hydrogel beads for cell barcoding and utilizes in vitro transcription (IVT) for amplification rather than PCR [1]. This linear amplification approach can reduce bias compared to PCR-based methods, though it may have lower overall efficiency. Like other droplet methods, inDrop offers low cost per cell and efficient barcode capture.

10x Genomics Chromium systems represent widely commercialized 3'-end approaches that use gel bead-in-emulsion (GEM) technology to partition single cells [3]. Within each GEM, gel beads dissolve to release barcoded oligos that label all transcripts from a single cell, ensuring traceability to cell of origin. This platform provides a robust, reproducible workflow suitable for large-scale studies across diverse sample types.

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of scRNA-seq Protocols

| Protocol | Transcript Coverage | UMI | Amplification Method | Throughput | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smart-Seq2 | Full-length | No | PCR | Low | Isoform analysis, allelic expression, low-abundance transcripts |

| FLASH-seq | Full-length | Optional | PCR | Low | High-sensitivity full-length profiling, rapid processing |

| MATQ-Seq | Full-length | Yes | PCR | Low | Quantifying transcripts, detecting variants |

| Drop-Seq | 3'-end | Yes | PCR | High | Large-scale atlas projects, heterogeneous samples |

| inDrop | 3'-end | Yes | IVT | High | Cost-effective large-scale studies |

| 10x Genomics | 3'-end | Yes | PCR | High | Standardized high-throughput profiling |

| CEL-Seq2 | 3'-end | Yes | IVT | Medium | Linear amplification, reduced bias |

| Seq-Well | 3'-end | Yes | PCR | Medium | Portable, low-cost applications |

Experimental Protocols and Workflow Specifications

Full-Length scRNA-seq Workflow

Full-length protocols begin with single-cell isolation, typically through fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) or microfluidic capture [1]. Cells are lysed to release RNA, followed by reverse transcription using oligo-dT primers that bind to polyadenylated tails. A critical distinction of full-length methods is the template-switching mechanism, where reverse transcriptase adds non-templated nucleotides to the 3' end of cDNA, enabling a template-switching oligonucleotide (TSO) to bind and extend, thus capturing the complete 5' end [4].

The resulting full-length cDNA undergoes PCR amplification to generate sufficient material for library construction. In FLASH-seq, key modifications include combining reverse transcription and cDNA preamplification, using Superscript IV reverse transcriptase for improved processivity, and optimizing nucleotide concentrations to enhance template-switching efficiency [4]. Library preparation typically involves tagmentation (tagged fragmentation) using Tn5 transposase, followed by limited-cycle PCR to add sequencing adapters.

3'-End scRNA-seq Workflow

3'-end protocols begin with creating viable single-cell suspensions through enzymatic or mechanical dissociation of tissues [3]. Critical quality control steps ensure appropriate cell concentration, viability, and absence of clumps or debris. Single cells are then partitioned into nanoliter-scale reactions using droplet microfluidics [1] [3].

In the 10x Genomics Chromium system, cells are co-encapsulated with barcoded gel beads in emulsion droplets (GEMs) [3]. Within each GEM, gel beads dissolve to release oligonucleotides containing cell-specific barcodes, unique molecular identifiers (UMIs), and poly(dT) sequences for mRNA capture. Cells are lysed within droplets, releasing RNA that is captured by the barcoded oligos. Reverse transcription occurs in isolation, labeling all cDNA from a single cell with the same barcode. After breaking emulsions, barcoded cDNA is pooled and amplified before library construction.

Performance Benchmarking and Experimental Data

Sensitivity and Throughput Comparisons

Direct comparisons between full-length and 3'-end protocols reveal trade-offs between sensitivity and throughput. FLASH-seq demonstrates superior sensitivity, detecting more genes per cell compared to other full-length methods including Smart-Seq2 and Smart-Seq3 across various sequencing depths [4]. This enhanced sensitivity enables detection of a more diverse set of isoforms and genes, particularly protein-coding and longer genes.

In contrast, 3'-end methods like Drop-Seq and 10x Genomics Chromium typically detect fewer genes per cell but profile orders of magnitude more cells [1]. This makes them preferable for comprehensive cell type identification in heterogeneous tissues. Benchmarking studies using mixture control experiments have systematically evaluated these trade-offs, with specific pipelines optimized for different analysis tasks including normalization, imputation, clustering, and trajectory analysis [5].

Table 2: Performance Metrics Across scRNA-seq Protocols

| Protocol | Genes Detected/Cell | Cells per Run | Cost per Cell | Hands-on Time | Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smart-Seq2 | 8,000-12,000 | 96-384 | High | High | Sensitivity, isoform detection |

| FLASH-seq | 10,000-14,000 | 96-384 | High | Medium | Speed, sensitivity, full-length coverage |

| Drop-Seq | 2,000-5,000 | 10,000+ | Low | Low | Scalability, cost-effectiveness |

| inDrop | 3,000-6,000 | 10,000+ | Low | Low | Linear amplification, reduced bias |

| 10x Genomics | 3,000-7,000 | 10,000+ | Medium | Medium | Standardization, reproducibility |

Analytical Considerations and Computational Requirements

The computational analysis of scRNA-seq data presents distinct challenges for full-length versus 3'-end protocols. Full-length data enables analysis of alternative splicing, isoform usage, and allele-specific expression but requires specialized tools for these applications and typically involves higher sequencing depth per cell [1] [6]. For 3'-end data, the incorporation of UMIs facilitates accurate transcript counting but provides limited information about transcript structure.

Benchmarking of computational pipelines for large-scale scRNA-seq datasets indicates that performance differences are largely driven by the choice of highly variable genes (HVGs) and principal component analysis (PCA) implementation [7]. Frameworks like OSCA and scrapper achieve high clustering accuracy (adjusted rand index up to 0.97) in datasets with known cell identities, while GPU-accelerated solutions like rapids-singlecell provide 15× speed-up over CPU methods with moderate memory usage [7]. These computational considerations should inform protocol selection based on available analytical resources and expertise.

Research Applications and Selection Guidelines

Domain-Specific Applications

The choice between full-length and 3'-end protocols depends significantly on the research domain and specific biological questions:

Cancer Research: scRNA-seq has revolutionized our understanding of tumor heterogeneity, microenvironment composition, and drug resistance mechanisms [1] [2]. Full-length protocols excel in characterizing splice variants and allele-specific expression in cancer cells, while 3'-end methods enable comprehensive profiling of diverse cell populations within tumors, including rare immune and stromal subsets.

Developmental Biology: Reconstructing developmental trajectories requires capturing transient intermediate states, making sensitivity a priority [1] [2]. Full-length protocols can detect low-abundance transcription factors critical for lineage specification. However, for comprehensive mapping of entire developmental programs, the higher throughput of 3'-end methods may be preferable.

Neurology: The exceptional cellular diversity of neural tissues benefits from high-throughput 3'-end profiling to comprehensively catalog cell types [2]. Full-length methods remain valuable for studying alternative splicing in neuronal genes and isoform diversity in different neural populations.

Immunology: Immune cell states span continuous spectra rather than discrete types, requiring technologies that balance throughput with sensitivity [1]. 3'-end methods efficiently profile large immune cell populations, while full-length approaches enable detailed characterization of T-cell and B-cell receptor repertoires.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for scRNA-seq

| Reagent/Material | Function | Protocol Applicability |

|---|---|---|

| Oligo-dT Primers | mRNA capture via poly-A tail binding | Universal |

| Template Switching Oligo (TSO) | Captures complete 5' end during reverse transcription | Full-length protocols (Smart-Seq2, FLASH-seq) |

| Barcoded Beads | Cell-specific labeling in partitioned reactions | 3'-end droplet protocols (Drop-Seq, 10x Genomics) |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Distinguishes biological duplicates from PCR duplicates | Primarily 3'-end protocols, some full-length (FS-UMI) |

| Tn5 Transposase | Fragments DNA and adds sequencing adapters simultaneously | Library preparation (especially FLASH-seq) |

| Reverse Transcriptase | Synthesizes cDNA from RNA template | Universal |

| Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Reagents | Amplifies cDNA for library construction | Universal |

Protocol Selection Framework

Selecting between full-length and 3'-end scRNA-seq protocols requires careful consideration of research goals, sample characteristics, and resource constraints:

Choose Full-Length Protocols When:

- Research questions involve alternative splicing, isoform usage, or RNA editing [1]

- Detection of low-abundance transcripts is critical [1] [4]

- Allele-specific expression analysis is required [1]

- Sample material is limited to few cells but deep molecular characterization is needed [1]

- Working with well-established cell lines or defined populations rather than highly heterogeneous tissues [4]

Choose 3'-End Protocols When:

- Studying highly heterogeneous tissues requiring profiling of thousands to millions of cells [1] [3]

- Research budget constraints necessitate lower cost per cell [3]

- Primary analysis goal is quantitative gene expression rather than transcript structure [6]

- Sample throughput is prioritized over complete transcript information [1]

- Working with sensitive primary cells that benefit from minimal processing time [3]

Emerging Solutions: Technological innovations continue to blur the distinctions between these approaches. Methods like FLASH-seq with UMIs combine full-length coverage with quantitative accuracy, while high-throughput 3'-end methods continue to improve gene detection sensitivity [4]. Researchers should monitor these developments as new protocols may offer preferable trade-offs for specific applications.

The dichotomy between full-length and 3'-end scRNA-seq protocols represents a fundamental trade-off between transcriptome completeness and experimental scale. Full-length methods provide comprehensive molecular information including isoform structure and sequence variants, making them ideal for mechanistic studies of transcriptional regulation. In contrast, 3'-end methods enable massive scaling for population-level studies, cellular atlas projects, and applications where quantitative accuracy and cost-effectiveness are prioritized.

Informed protocol selection requires alignment between methodological capabilities and research objectives, considering factors including sample type, cellular heterogeneity, biological questions, and analytical resources. As benchmarking efforts continue to refine our understanding of protocol performance across diverse applications, and as technological innovations further enhance both sensitivity and throughput, researchers are increasingly empowered to select optimal approaches for their specific experimental needs. The ongoing development of computational tools and analysis pipelines will further enhance the utility of both approaches, cementing scRNA-seq's transformative role in biomedical research.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized biological research by enabling the study of gene expression at the resolution of individual cells, revealing cellular heterogeneity that is obscured in bulk RNA-seq experiments [8] [9]. Since its conceptual breakthrough in 2009, scRNA-seq technology has evolved rapidly, with throughput increasing from a few cells per experiment to hundreds of thousands of cells while costs have dramatically decreased [8]. The fundamental goal of scRNA-seq is to transform biological samples into digital gene expression data that can computationally interrogate cellular composition and function.

The complete scRNA-seq workflow encompasses both wet-lab experimental procedures and computational analysis steps. This guide focuses specifically on the stages from physical cell isolation through the generation of count matrices—the critical foundation upon which all subsequent biological interpretations are built. These initial steps determine data quality and reliability, making their proper execution essential for valid scientific conclusions [8] [10]. Within benchmarking studies for scRNA-seq analysis pipelines, understanding these foundational steps is crucial for evaluating how methodological choices influence downstream results and comparative performance metrics [11].

Experimental Procedures: From Tissue to Library Preparation

Single-Cell Isolation and Capture

The initial critical step in scRNA-seq involves creating a high-quality single-cell suspension from tissue while preserving cellular integrity and RNA content. The choice of isolation method depends on the organism, tissue type, and cell properties [8] [12].

Common single-cell isolation techniques include:

- Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS): Uses fluorescent labeling to sort individual cells based on specific markers

- Magnetic-Activated Cell Sorting (MACS): Employs magnetic beads conjugated to antibodies for cell separation

- Microfluidic Systems: Utilize microfluidic chips to precisely control cell placement

- Droplet-Based Technologies: Encapsulate individual cells in oil droplets using microfluidic systems [8] [13]

- Combinatorial In-Situ Barcoding: Involves fixation and permeabilization of cells, allowing each cell to act as its own reaction compartment [13]

A significant technical challenge during tissue dissociation is the induction of "artificial transcriptional stress responses" where the dissociation process itself alters gene expression patterns [8]. Studies have confirmed that protease dissociation at 37°C can induce stress gene expression, leading to inaccurate cell type identification [14] [9]. To minimize these artifacts, dissociation at 4°C has been suggested, or alternatively, using single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) which sequences nuclear mRNA and minimizes stress responses [8]. snRNA-seq is particularly valuable for tissues difficult to dissociate into single-cell suspensions, such as brain tissue [8] [15].

Table 1: Comparison of Single-Cell Isolation Methods

| Method | Throughput | Principle | Key Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Droplet-Based (10x Genomics, inDrop, Drop-seq) | High (thousands to millions of cells) | Microfluidic partitioning of cells into oil droplets | Large-scale atlas building, heterogeneous tissues | Requires specialized equipment; not ideal for very large or irregular cells [13] |

| Combinatorial Barcoding | Medium to High | Fixed, permeabilized cells barcoded in multi-well plates | Frozen/archived samples, complex tissues | Minimal equipment needed; enables sample multiplexing [13] |

| FACS | Medium | Fluorescent antibody-based cell sorting | Studies requiring specific cell populations | Requires known surface markers; moderate throughput [8] |

| Plate-Based (Smart-seq2) | Low | Manual or robotic cell picking into well plates | Studies requiring full-length transcript coverage | Higher cost per cell; labor-intensive [16] |

Library Preparation and Barcoding Strategies

Following cell isolation, library preparation converts cellular RNA into sequencing-ready libraries through several molecular biology steps. The core process includes cell lysis, reverse transcription (converting RNA to cDNA), cDNA amplification, and library preparation [8]. A critical innovation in scRNA-seq is the use of cellular barcodes to tag all mRNAs from an individual cell, and unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to label individual mRNA molecules [10] [16].

Key barcoding approaches include:

- Cellular Barcodes: Short nucleotide sequences that uniquely identify each cell, allowing bioinformatic separation of cells after sequencing [16]

- Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs): Random nucleotide sequences (4-10 bp) that tag individual mRNA molecules, enabling distinction between biological duplicates and technical PCR amplification duplicates [8]

Two main cDNA amplification strategies are employed in scRNA-seq protocols. PCR amplification (used in Smart-seq2, 10x Genomics, Drop-seq) provides non-linear amplification through polymerase chain reaction [8]. In vitro transcription (IVT) (used in CEL-seq, MARS-Seq) employs linear amplification through T7 in vitro transcription [8]. PCR-based methods generally show higher sensitivity, while IVT methods may introduce 3' coverage biases [8]. The incorporation of UMIs has significantly improved the quantitative nature of scRNA-seq by effectively eliminating PCR amplification bias [8].

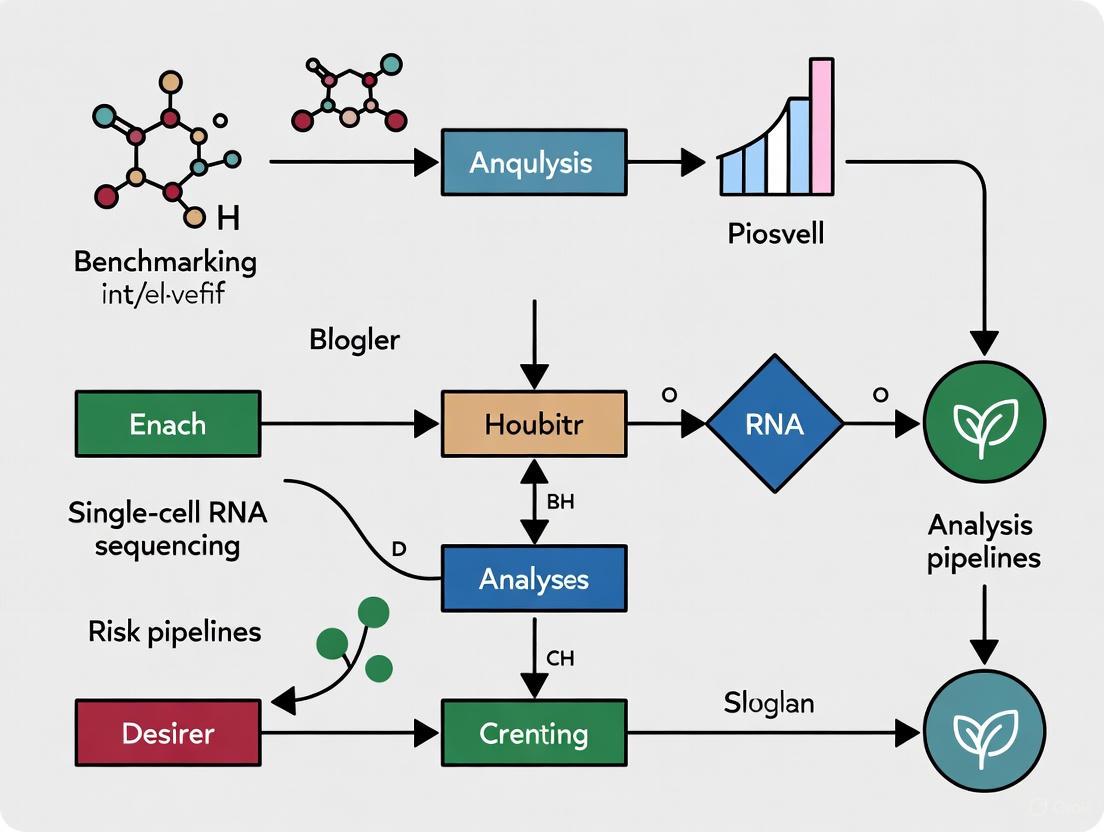

Diagram 1: Experimental scRNA-seq workflow from cell isolation to library preparation.

Computational Processing: From Raw Sequences to Count Matrix

Sequencing Data Processing

After sequencing, the raw data undergoes computational processing to generate gene expression count matrices. The starting point is typically FASTQ files, which contain nucleotide sequences and associated quality scores [13] [16]. The specific processing steps vary depending on the library preparation method, particularly in how barcodes, UMIs, and sample indices are arranged in the sequencing reads [16].

Core processing steps include:

- Formatting Reads and Filtering Barcodes: Extraction of cellular barcodes and UMIs from raw sequences, followed by filtering of low-quality barcodes [16]

- Demultiplexing Samples: Separation of sequencing data from multiple samples based on sample indices [16]

- Read Alignment: Mapping of sequences to a reference genome using aligners like STAR or light-weight mapping tools like Kallisto [13] [16]

- UMI Collapsing and Quantification: Deduplication of reads with identical UMIs mapping to the same gene, followed by counting unique UMIs per gene per cell [16]

For 10x Genomics data, the Cell Ranger pipeline performs all these steps automatically, while for other methods, tools like umis or zUMIs can be used [12] [16]. The final output is a count matrix where rows represent genes, columns represent cells, and values indicate the number of unique UMIs detected for each gene in each cell [13] [16].

UMI Processing and Quantification

The handling of UMIs is particularly important for accurate quantification in 3' end sequencing protocols (10x Genomics, Drop-seq, inDrops). The fundamental principle is:

- Reads with different UMIs mapping to the same transcript represent biological duplicates and should each be counted [16]

- Reads with the same UMI mapping to the same transcript represent technical duplicates (PCR duplicates) and should be collapsed to a single count [16]

This UMI collapsing corrects for amplification bias that would otherwise overrepresent highly amplified molecules, providing more accurate quantitative data [8].

Diagram 2: Computational processing from FASTQ files to count matrix with UMI handling.

Quality Assessment and Method Comparison

Quality Control Metrics for Raw Data

Quality assessment begins immediately after generating initial count matrices. Key quality control (QC) metrics help identify low-quality cells and potential technical artifacts [10] [12]. The three primary QC covariates are:

- Count Depth: Total number of counts per barcode

- Genes Detected: Number of genes detected per barcode

- Mitochondrial Fraction: Fraction of counts originating from mitochondrial genes [10]

Cells with low count depth, few detected genes, and high mitochondrial fraction often represent dying cells or broken cells where cytoplasmic mRNA has leaked out, leaving only mitochondrial mRNA [10]. Conversely, cells with unusually high counts and gene numbers may represent multiplets (doublets) where two or more cells share the same barcode [10]. For droplet-based methods, empty droplets or droplets containing ambient RNA must also be identified and filtered out [13].

Mitochondrial read fraction is particularly informative for cell viability assessment. As cell membranes become compromised, cytoplasmic RNAs leak out while mitochondrial RNAs remain intact within mitochondria, leading to elevated mitochondrial fractions [13]. Commonly used thresholds for mitochondrial read filtration range from 10-20%, though this varies by cell type [13]. Stressed cells or specific cell types with naturally high mitochondrial content (e.g., cardiomyocytes) may require adjusted thresholds to avoid excluding biologically relevant populations [13] [12].

Table 2: Quality Control Metrics and Filtering Approaches

| QC Metric | Interpretation | Filtering Approach | Common Thresholds |

|---|---|---|---|

| Count Depth | Total transcripts per cell | Remove outliers with unusually high or low counts | Varies by protocol; often 500-10,000 UMI/cell [10] |

| Genes Detected | Complexity of transcriptome | Filter cells with too few or too many genes detected | Typically 200-500 minimum genes/cell [13] |

| Mitochondrial Fraction | Indicator of cell stress/viability | Exclude cells with high mitochondrial content | 10-20% for most cells; cell-type dependent [13] [12] |

| Doublet Rate | Multiple cells sharing barcode | Bioinformatic detection using Scrublet, DoubletFinder | Expected rate depends on cell loading density [13] [10] |

| Ambient RNA | Background free-floating RNA | Computational removal with SoupX, CellBender | Particularly important in droplet-based methods [13] [12] |

Comparative Analysis of scRNA-seq Methods

Different scRNA-seq methodologies offer distinct advantages depending on the biological question. The choice between 3' end sequencing and full-length sequencing involves important trade-offs:

3' End Sequencing (10x Genomics, Drop-seq, inDrops):

- More accurate quantification through UMIs

- Larger number of cells sequenced

- Lower cost per cell

- Ideal for studies with >10,000 cells [16]

Full-Length Sequencing (Smart-seq2):

- Detection of isoform-level expression differences

- Identification of allele-specific expression

- Deeper sequencing of fewer cells

- Better for samples with limited cell numbers [16]

For benchmarking studies, understanding these methodological differences is crucial when evaluating analytical pipeline performance. The Integrated Benchmarking scRNA-seq Analytical Pipeline (IBRAP) demonstrates that optimal pipelines depend on individual samples and studies, emphasizing the need for flexible benchmarking approaches [11].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for scRNA-seq

| Category | Specific Products/Tools | Function | Protocol Compatibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial Kits | 10x Genomics Chromium, SMARTer, Nextera | Complete workflows from cell to library | Platform-specific [15] [9] |

| Cell Separation | FACS, MACS, Microfluidic chips | Isolation of specific cell populations | All protocols [8] |

| Amplification Chemistry | SMARTer, Template switching oligos | cDNA amplification from limited input | Full-length protocols (Smart-seq2) [8] |

| Library Prep | Illumina Nextera, Custom barcoding | Preparation of sequencing-ready libraries | All protocols [15] |

| Alignment Tools | STAR, Kallisto, bustools | Read mapping to reference genome | All protocols [13] [16] |

| UMI Processing | umis, zUMIs, Cell Ranger | UMI collapsing and quantification | 3' end protocols [16] |

| QC & Filtering | Scrublet, DoubletFinder, SoupX | Quality control and artifact removal | All protocols [13] [10] |

| Visualization | Loupe Browser, Seurat, Scanpy | Data exploration and analysis | Platform-specific and general [12] [9] |

The journey from cell isolation to count matrices represents the foundational phase of scRNA-seq analysis where technical decisions profoundly impact data quality and reliability. The key steps—cell isolation, library preparation, barcode/UMI processing, and initial quality control—establish the groundwork for all subsequent biological interpretations. As benchmarking studies like IBRAP have demonstrated, the optimal analytical approaches are context-dependent, influenced by both biological sample characteristics and technical methodologies [11].

Understanding these foundational steps is essential for rigorous experimental design and appropriate interpretation of scRNA-seq data, particularly as the technology continues to evolve toward higher throughput, reduced costs, and integration with other single-cell modalities. By systematically addressing potential pitfalls at each stage—from artificial stress responses during cell dissociation to ambient RNA contamination in droplet-based systems—researchers can generate high-quality count matrices that faithfully represent the underlying biology and enable robust scientific discovery.

Within the broader thesis of benchmarking single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) analysis pipelines, understanding data quality and noise is paramount. The performance of any pipeline is intrinsically linked to the quality of the input data, which is invariably affected by multiple sources of technical noise. The choices made in preprocessing and analysis can have an impact as significant as quadrupling the sample size [17]. This guide provides a comparative overview of critical data quality metrics, common noise sources, and the methodologies used to evaluate them in the context of scRNA-seq pipeline benchmarking.

Critical Data Quality Metrics in scRNA-seq

High-quality scRNA-seq data is the foundation for reliable biological insights. The table below summarizes the key quantitative metrics used to assess data quality, their definitions, and benchmarks derived from large-scale evaluations.

Table 1: Key scRNA-seq Data Quality Metrics and Benchmarks

| Metric Category | Specific Metric | Definition and Purpose | Recommended Benchmark |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Depth | Cells / Cell Type / Individual | The number of cells sequenced per cell type per individual to ensure reliable quantification [18]. | At least 500 cells [18]. |

| Data Structure & Clustering | Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) | Measures the agreement between computational clustering and known cell type labels [19]. | Higher values indicate better clustering (e.g., net-SNE achieved ARI comparable to t-SNE [19]). |

| Mean Silhouette Coefficient (SIL) | An unsupervised metric evaluating how similar a cell is to its own cluster compared to other clusters [20]. | Corrected values are used to compare pipelines independent of cluster count [20]. | |

| Calinski-Harabasz (CH) & Davies-Bouldin (DB) Index | Unsupervised metrics evaluating cluster separation and compactness [20]. | Corrected values are used for pipeline comparison [20]. | |

| Gene Expression Quantification | Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) | Identifies reproducible differentially expressed genes [18]. | Higher values indicate more reliable differential expression results. |

| Cross-Modality Quality (CITE-Seq) | Normalized Shannon Entropy | Quantifies the cell type-specificity of a gene or surface protein's expression [21]. | Lower entropy indicates more specific, higher-quality markers [21]. |

| RNA-ADT Correlation | Spearman’s correlation between gene expression and corresponding protein abundance [21]. | A positive correlation is expected for high-quality data [21]. |

Technical noise in scRNA-seq data obscures biological signals and poses significant challenges for downstream analysis. The following are the most prevalent sources of noise.

- Technical Dropouts: A predominant source of noise, dropouts are zero counts where a gene is expressed but not detected due to technical limitations. This high sparsity complicates the identification of subtle biological phenomena, such as tumor-suppressor events [22].

- Batch Effects: These are non-biological variations introduced across different datasets, experiments, or sequencing runs due to differences in reagents, instruments, or protocols. Batch effects distort comparative analyses and impede the consistency of findings [22].

- Library Size Variation: Cell-to-cell variability in the total number of sequenced molecules, often related to differences in cell size or sampling efficiency, can be a major confounder [23] [24].

- The Curse of Dimensionality: The high-dimensional nature of scRNA-seq data means that technical noise accumulates across many genes, which can obscure the true underlying data structure [22].

The diagram below illustrates the sources of noise and the stages at which they are introduced and mitigated in a typical scRNA-seq workflow.

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

To objectively compare the performance of different analysis tools and pipelines, standardized benchmarking experiments are crucial. The following protocols detail key methodologies cited in the literature.

Protocol 1: Evaluating scRNA-seq Pipeline Performance Using Silhouette Coefficient

This protocol measures how well a pipeline recovers known cell populations using an unsupervised metric [20].

- Data Preparation: Obtain an scRNA-seq dataset with known ground-truth cell type labels or a validated clustering structure.

- Pipeline Application: Apply the scRNA-seq analysis pipeline (e.g., a specific combination of normalization, dimensionality reduction, and clustering methods) to the dataset.

- Cluster Generation: Generate cell cluster assignments from the pipeline output.

- Metric Calculation: For the Silhouette Coefficient (SIL):

- For each cell ( i ), calculate ( s(i) = \frac{b(i) - a(i)}{\max{a(i), b(i)}} ), where ( a(i) ) is the mean distance between cell ( i ) and all other cells in the same cluster, and ( b(i) ) is the mean distance between cell ( i ) and all cells in the nearest neighboring cluster.

- The overall SIL score is the mean of ( s(i) ) over all cells.

- Correction for Cluster Number: To avoid bias from the number of clusters ( k ), regress the SIL scores against ( k ) using a loess model across many pipelines. Use the residuals of this regression as the corrected SIL metric for unbiased pipeline comparison [20].

Protocol 2: Assessing Data Integration and Batch Correction Using iLISI

This protocol evaluates a method's ability to remove batch effects while preserving biological variation using the integration Local Inverse Simpson's Index (iLISI) score [22].

- Data Collection: Combine scRNA-seq datasets from multiple batches (e.g., different experiments or protocols) that profile the same or similar cell types.

- Integration: Apply the batch-correction method (e.g., Harmony, Scanorama, or iRECODE) to the combined dataset.

- Neighborhood Analysis: Following integration, compute a k-nearest neighbor (k-NN) graph (e.g., k=90) in the corrected latent space for all cells.

- LISI Score Calculation:

- For each cell, examine its local neighborhood (including itself, for a total of k+1 cells).

- Calculate the Inverse Simpson's Index for the batch labels within this neighborhood. A high index indicates a diverse mix of batches in the neighborhood.

- The iLISI score for the dataset is the median of these indices across all cells. A higher iLISI score indicates better mixing of batches and, therefore, more effective batch correction [22].

Protocol 3: Validating Denoising Methods with Differential Expression Analysis

This protocol tests whether a denoising method improves the accuracy of identifying true differentially expressed (DE) genes by validating results against a ground truth, such as bulk RNA-seq data [23].

- Data Acquisition: Acquire a sample-matched scRNA-seq dataset and a bulk RNA-seq dataset from the same biological source.

- Denoising: Apply the denoising method (e.g., ZILLNB, RECODE, DCA) to the raw scRNA-seq count matrix to generate a denoised matrix.

- Differential Expression Testing: Perform DE analysis on both the raw and the denoised scRNA-seq data between two predefined cell groups or conditions.

- Ground Truth Comparison: Using the bulk RNA-seq data as a reference, calculate the Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUC-PR) or the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC-ROC) for the DE results from both the raw and denoised data.

- Performance Quantification: An effective denoising method will show a significant improvement (e.g., 0.05 to 0.3 increase) in AUC-PR or AUC-ROC compared to the raw data, indicating a higher power to detect true biological differences [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Computational Tools

The following table lists essential computational tools and resources used in the field for scRNA-seq data quality control and noise mitigation.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for scRNA-seq QC and Noise Reduction

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| CITESeQC [21] | R Software Package | Multi-layered quality control for CITE-Seq data. | Quantifies RNA and protein data quality and their interactions using entropy and correlation. |

| RECODE / iRECODE [22] | Algorithm | Technical noise and batch effect reduction. | Uses high-dimensional statistics to denoise various data types (RNA, Hi-C, spatial). |

| scran [17] | R Package | Normalization of scRNA-seq count data. | Pooling-based size factor estimation, robust to asymmetric expression differences. |

| ZILLNB [23] | Computational Framework | Denoising scRNA-seq data. | Integrates deep learning with Zero-Inflated Negative Binomial regression. |

| Harmony [22] | Algorithm | Batch effect correction and dataset integration. | Often used within integrated platforms like iRECODE for batch correction. |

| net-SNE [19] | Visualization Tool | Scalable, generalizable low-dimensional embedding. | Uses a neural network to project new cells onto an existing visualization. |

Comparative Performance of Analysis Methods

Benchmarking studies reveal that the performance of computational methods is highly dependent on the dataset and the specific analytical goal. The table below summarizes comparative experimental data for several key tasks.

Table 3: Comparative Performance Data of scRNA-seq Methods

| Analysis Task | Method | Performance | Comparison Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Denoising | ZILLNB [23] | Achieved ARI improvements of 0.05-0.2 over VIPER, scImpute, DCA, etc. | Cell type classification on mouse cortex & human PBMC datasets. |

| ZILLNB [23] | AUC-ROC/AUC-PR improvements of 0.05-0.3 over standard methods. | Differential expression analysis validated against bulk RNA-seq. | |

| Normalization | scran & SCnorm [17] | Maintained False Discovery Rate (FDR) control in asymmetric DE setups. | Evaluation across ~3000 simulated DE-setups. |

| Logarithm w/ pseudo-count [24] | Performed as well as or better than more sophisticated alternatives. | Benchmark of transformation approaches on simulated and real data. | |

| Batch Correction | iRECODE [22] | Reduced relative error in mean expression from 11.1-14.3% to 2.4-2.5%. | Integration of scRNA-seq data from three datasets and two cell lines. |

| Visualization | net-SNE [19] | Achieved clustering accuracy comparable to t-SNE. | Visualization quality and clustering on 13 datasets. |

| net-SNE [19] | Reduced runtime for 1.3 million cells from 1.5 days to 1 hour. | Scalability test on a large mouse neuron dataset. |

The Impact of Library Preparation Protocols on Downstream Analysis Outcomes

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized biological research by enabling the investigation of cellular heterogeneity, identification of rare cell types, and characterization of transcriptional dynamics at unprecedented resolution [25] [26]. As the field progresses toward larger atlas-building initiatives and clinical applications, the critical importance of library preparation protocols in determining data quality and analytical outcomes has become increasingly apparent [27] [28]. The selection of an appropriate scRNA-seq method represents a fundamental decision that establishes boundaries for all subsequent biological interpretations, influencing sensitivity, accuracy, and the specific research questions that can be addressed [25] [29].

Library preparation protocols for scRNA-seq encompass diverse methodologies that differ significantly in their molecular biology, throughput capabilities, and analytical strengths [30]. These technical variations systematically influence downstream results including gene detection sensitivity, ability to identify cell types, detection of isoforms, and accuracy in quantifying gene expression levels [31] [29]. As research expands into more complex biological systems and challenging sample types—including clinical specimens with inherent limitations—understanding these methodological impacts becomes essential for robust experimental design and data interpretation [28] [32].

This review synthesizes recent evidence comparing scRNA-seq library preparation methods, with a specific focus on their performance characteristics and implications for downstream analysis. By examining experimental data across multiple platforms and applications, we provide a framework for researchers to match protocol selection with specific research objectives within the broader context of benchmarking single-cell RNA sequencing analysis pipelines.

scRNA-seq Protocol Classifications and Key Characteristics

Single-cell RNA sequencing technologies can be broadly categorized based on their fundamental technical approaches, each with distinct implications for experimental design and analytical outcomes [25] [30]. The three primary categories are plate-based, droplet-based, and combinatorial indexing methods, which differ in throughput, gene detection capability, and applications [30] [29].

Plate-based methods represent the earliest approach to scRNA-seq and include protocols such as SMART-seq2, SMART-seq3, and Fluidigm C1 [30] [29]. These methods typically process cells in individual wells of multiwell plates, allowing for quality control steps including microscopic verification of single-cell capture and viability assessment [33]. A key advantage of plate-based methods is their ability to generate full-length transcript coverage, enabling analysis of alternative splicing, isoform usage, and RNA editing [25] [29]. These protocols generally demonstrate higher sensitivity in gene detection per cell compared to high-throughput methods, making them particularly suitable for applications requiring comprehensive transcriptome characterization from limited cell numbers [29]. The primary limitation of plate-based approaches is their relatively low throughput, typically processing hundreds rather than thousands of cells, along with higher cost per cell and greater hands-on time [30] [29].

Droplet-based methods, including commercial platforms such as 10x Genomics Chromium, Drop-Seq, and inDrop, utilize microfluidic technology to encapsulate individual cells in oil droplets together with barcoded beads [27] [25]. These methods excel in high-throughput applications, enabling profiling of tens of thousands of cells in a single experiment [30]. This scalability makes droplet-based approaches ideal for comprehensive characterization of complex tissues, identification of rare cell populations, and large-scale atlas projects [25]. Most droplet-based methods are limited to 3' or 5' transcript counting rather than full-length transcript analysis, which restricts their utility for isoform-level investigations [25] [30]. While offering lower sequencing costs per cell, they typically demonstrate reduced genes detected per cell compared to plate-based methods [29].

Combinatorial indexing approaches, such as sci-RNA-seq and SPLiT-seq, utilize sequential barcoding strategies without physical isolation of single cells [30]. These methods can achieve extremely high throughput at very low cost per cell, making them suitable for projects requiring massive cell numbers [30]. They eliminate the need for specialized microfluidic equipment but may present computational challenges during demultiplexing [30].

Table 1: Classification of Major scRNA-seq Protocol Types

| Category | Examples | Throughput | Transcript Coverage | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plate-based | SMART-seq2, SMART-seq3, Fluidigm C1, G&T-seq | Low (10-1,000 cells) | Full-length | High gene detection, isoform information | Low throughput, high cost per cell |

| Droplet-based | 10x Genomics, Drop-Seq, inDrop, Seq-Well | High (1,000-80,000 cells) | 3' or 5' counting | High throughput, cost-effective | Limited to gene counting, lower sensitivity |

| Combinatorial Indexing | sci-RNA-seq, SPLiT-seq | Very high (>10,000 cells) | 3' counting | Extreme throughput, low cost per cell | Complex barcode deconvolution |

The molecular implementation of these protocols further differentiates their capabilities. Full-length methods like SMART-seq2 utilize template-switching mechanisms to capture complete transcripts, enabling detection of single nucleotide variants, isoform diversity, and RNA editing events [25] [29]. In contrast, 3' end counting methods focus on digital quantification of transcript molecules through unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) that mitigate amplification biases, providing more accurate quantification of gene expression levels but losing structural information about transcripts [25] [30]. The incorporation of UMIs has become standard in high-throughput protocols including 10x Genomics, Drop-Seq, and MARS-seq, significantly improving the quantitative accuracy of transcript counting [25] [30].

Comparative Performance of scRNA-seq Protocols

Gene Detection Sensitivity and Technical Performance

Systematic comparisons of scRNA-seq protocols reveal substantial differences in sensitivity, precision, and technical performance that directly impact downstream analytical outcomes. A comprehensive benchmarking of four plate-based full-length transcript protocols—NEBnext, Takara SMART-seq HT, G&T-seq, and SMART-seq3—demonstrated significant variation in gene detection capability and cost efficiency [29]. Among these protocols, G&T-seq delivered the highest detection of genes per single cell, while SMART-seq3 provided the highest gene detection at the lowest price point [29]. The Takara kit demonstrated similar high gene detection per cell with excellent reproducibility between samples but at a substantially higher cost [29].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Plate-Based Full-Length scRNA-seq Protocols [29]

| Protocol | Average Genes Detected Per Cell | Cost Per Cell (€) | Reproducibility | Hands-On Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G&T-seq | Highest | 12 | High | High |

| SMART-seq3 | High | Lowest | High | Medium |

| Takara SMART-seq HT | High | 73 | Highest | Low |

| NEBnext | Lower | 46 | Medium | Low |

Droplet-based methods generally detect fewer genes per cell compared to plate-based approaches but enable analysis of significantly more cells. For example, a comparative analysis of SUM149PT cells across five platforms (Fluidigm C1, Fluidigm HT, 10x Genomics Chromium, BioRad ddSEQ, and WaferGen ICELL8) revealed platform-specific differences in sensitivity and cell capture efficiency [33]. The Fluidigm C1 system, a plate-based approach, demonstrated superior gene detection per cell, while the 10x Genomics Chromium platform provided a balance of reasonable gene detection with substantially higher throughput [33].

Technical performance metrics also vary considerably in applications involving challenging sample types. In profiling neutrophils—cells with particularly low RNA content and high RNase levels—recent comparisons of 10x Genomics Flex, Parse Biosciences Evercode, and Honeycomb Biotechnologies HIVE revealed distinct performance characteristics [28]. The Parse Biosciences Evercode platform showed the lowest levels of mitochondrial gene expression, suggesting better preservation of RNA quality, while technologies using non-fixed cells as input had higher levels of mitochondrial genes, potentially indicating increased cell stress [28]. For neutrophil studies, which are important in clinical biomarker research but technically challenging, these performance differences directly influence data quality and utility for downstream analysis [28].

Methodological Comparisons in Specialized Applications

The impact of library preparation protocols extends to specialized applications including full-length isoform detection, FFPE sample analysis, and time-resolved transcriptional studies. Third-generation sequencing (TGS) technologies utilizing long-read sequencing from Oxford Nanopore (ONT) and Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) have been integrated with scRNA-seq to enable full-length transcript characterization [31]. A systematic evaluation of these platforms demonstrated that while both ONT and PacBio can accurately capture cell types, they exhibit distinct strengths: PacBio demonstrated superior performance in discovering novel transcripts and specifying allele-specific expression, while ONT generated more cDNA reads but with lower quality cell barcode identification [31].

For formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples—a valuable resource in clinical research—library preparation methods must overcome RNA degradation and chemical modifications. A direct comparison of TaKaRa SMARTer Stranded Total RNA-Seq Kit v2 and Illumina Stranded Total RNA Prep Ligation with Ribo-Zero Plus revealed that despite important technical differences, both kits generated highly concordant gene expression profiles [32]. The TaKaRa kit achieved comparable performance with 20-fold less RNA input, a crucial advantage for limited clinical samples, though with increased sequencing depth requirements [32]. Both methods showed high correlation in housekeeping gene expression (R² = 0.9747) and significant overlap in differentially expressed genes (83.6-91.7%), demonstrating that despite technical differences, robust biological conclusions can be drawn from properly optimized FFPE-compatible protocols [32].

In time-resolved scRNA-seq using metabolic RNA labeling, the choice of chemical conversion method and platform compatibility significantly impacts the accuracy of RNA dynamics measurements. A comprehensive benchmarking of ten chemical conversion methods using the Drop-seq platform identified that on-beads methods, particularly meta-chloroperoxy-benzoic acid/2,2,2-trifluoroethylamine (mCPBA/TFEA) combinations, outperformed in-situ approaches in conversion efficiency [34]. The mCPBA/TFEA pH 5.2 reaction minimally compromised library complexity while maintaining high T-to-C substitution rates (8.11%), crucial for accurate detection of newly synthesized RNA [34]. When applied to zebrafish embryogenesis, these optimized methods enhanced zygotic gene detection capabilities, demonstrating the critical importance of protocol selection for studying dynamic biological processes [34].

Experimental Methodologies for Protocol Benchmarking

Standardized Comparative Frameworks

Rigorous benchmarking of scRNA-seq protocols requires carefully controlled experimental designs that enable direct comparison across methods while minimizing biological variability. A widely adopted approach utilizes well-characterized cell lines or synthetic tissue mixtures with known cellular composition, allowing technical performance to be assessed without confounding biological heterogeneity [27] [33]. In one such study, SUM149PT cells—a human breast cancer cell line—were treated with trichostatin A (a histone deacetylase inhibitor) or vehicle control, then distributed to multiple laboratories for parallel analysis across different platforms including Fluidigm C1, 10x Genomics Chromium, WaferGen ICELL8, and BioRad ddSEQ [33]. This design enabled direct comparison of each platform's ability to detect the transcriptional changes induced by TSA treatment, with bulk RNA-seq data serving as a reference benchmark [33].

Alternative approaches utilize synthetic tissue mixtures created by combining distinct cell types at known ratios. The Human Cell Atlas benchmarking project employed this strategy, comparing Drop-Seq, Fluidigm C1, and DroNC-Seq technologies using a synthetic tissue created from mixtures of multiple cell types at predetermined ratios [27]. This methodology allows precise assessment of each protocol's sensitivity in detecting rare cell populations, accuracy in quantifying cell type proportions, and specificity in distinguishing closely related cell states [27].

Standardized metrics for protocol evaluation typically include:

- Gene detection sensitivity: Number of genes detected per cell across a range of sequencing depths

- Transcript quantification accuracy: Correlation with bulk RNA-seq or qPCR measurements

- Cell type identification: Ability to resolve known biological populations

- Technical variability: Measure of reproducibility across technical replicates

- Doublet rates: Frequency of multiple cells being captured as single cells

- Cell-free RNA contamination: Level of ambient RNA background

- Sequence quality metrics: Mapping rates, duplication rates, and base quality scores

Specialized Applications and Sample-Specific Protocols

Benchmarking methodologies must be adapted when evaluating protocol performance for specialized applications or challenging sample types. For profiling sensitive cell populations like neutrophils, standardized blood samples from healthy donors are processed in parallel across different technologies, with flow cytometry analysis providing ground truth for cell type composition [28]. This approach revealed that technologies such as Parse Biosciences Evercode and 10x Genomics Flex could capture neutrophil transcriptomes despite their technical challenges, with each method showing distinct strengths in RNA quality preservation and cell type representation [28].

When comparing protocols for FFPE samples, the benchmarking methodology must account for RNA quality variations and extraction efficiency. The comparative analysis of TaKaRa and Illumina FFPE-compatible kits utilized RNA isolated from melanoma patient samples with DV200 values (percentage of RNA fragments >200 nucleotides) ranging from 37% to 70%, representing typically degraded FFPE RNA [32]. Performance was assessed through multiple metrics including alignment rates, ribosomal RNA content, duplication rates, and concordance in differential expression analysis, providing a comprehensive view of each method's strengths and limitations for degraded samples [32].

For evaluating full-length transcript protocols, benchmarking extends beyond gene counting to include isoform detection accuracy, allele-specific expression quantification, and identification of novel transcripts. The evaluation of third-generation sequencing platforms for scRNA-seq utilized mouse embryonic tissues and directly compared PacBio and Oxford Nanopore technologies against next-generation sequencing controls [31]. This systematic assessment examined performance in isoform discovery, cell barcode identification, allele-specific expression analysis, and accuracy in novel isoform detection, revealing platform-specific biases that influence analytical outcomes [31].

Experimental Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: scRNA-seq Protocol Selection Workflow. This decision tree guides researchers in selecting appropriate library preparation methods based on experimental requirements and sample characteristics.

Impact on Downstream Analytical Outcomes

Cell Type Identification and Transcriptome Characterization

The choice of library preparation protocol profoundly impacts the ability to resolve cell types and states in downstream analysis. Methods with higher gene detection sensitivity, such as plate-based full-length protocols, typically enable finer resolution of closely related cell populations and more confident identification of rare cell types [29]. In benchmarking studies, SMART-seq3 and G&T-seq demonstrated superior detection of genes per cell, which directly translated to enhanced ability to distinguish subtle transcriptional differences between similar cell states [29]. This high sensitivity is particularly valuable in developmental biology and cancer research, where continuous differentiation trajectories or tumor subclones require resolution of fine transcriptional gradients.

In contrast, high-throughput droplet methods trade some sensitivity for vastly increased cell numbers, enabling identification of very rare cell populations through quantitative abundance rather than deep transcriptional profiling [25]. For atlas-level projects aiming to comprehensively catalog all cell types in complex tissues, the 10x Genomics Chromium platform has become a dominant choice due to its balance of reasonable gene detection with massive scalability [27] [25]. The impact on cell type identification was clearly demonstrated in a multi-platform comparison where each technology successfully detected major cell populations but differed in resolution of fine subtypes and detection rates for very rare cells [33].

Protocol selection also influences the biological interpretations derived from clustering analysis. Methods with strong 3' bias may underrepresent certain transcript classes or fail to detect isoforms that are predominantly expressed through 5' sequences [25]. Additionally, protocols with higher technical variability or batch effects can introduce spurious clusters that do not correspond to genuine biological states, complicating interpretation and requiring more sophisticated normalization approaches [25] [31].

Differential Expression and Quantitative Accuracy

The quantitative accuracy of gene expression measurement varies significantly across scRNA-seq protocols, directly impacting power in differential expression analysis. Protocols incorporating unique molecular identifiers (UMIs), including most droplet-based methods and the newer SMART-seq3 platform, provide more accurate transcript counting by correcting for amplification biases [30] [29]. In comparative studies, UMI-based methods typically demonstrate better agreement with RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) validation data and more precise estimation of fold-changes in differential expression analysis [29].

The choice between full-length and 3'-end counting protocols also influences which types of differential expression can be detected. Full-length methods enable differential analysis of isoform usage and allele-specific expression, providing mechanistic insights beyond simple gene-level regulation [31] [29]. In evaluations of third-generation sequencing platforms, PacBio demonstrated superior performance in identifying allele-specific expression, enabling studies of regulatory variation and genomic imprinting that are not possible with 3'-end counting methods [31].

Technical performance in challenging samples directly affects the reliability of differential expression results. In FFPE samples, both TaKaRa and Illumina kits showed high concordance (83.6-91.7% overlap) in differentially expressed genes despite important technical differences in library preparation chemistry [32]. Similarly, in neutrophil profiling, protocols that better preserved RNA quality (as indicated by lower mitochondrial gene expression) yielded more reliable differential expression results between activation states [28]. These findings highlight that while absolute expression values may vary between protocols, properly optimized methods can generate consistent biological conclusions regarding differential expression.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for scRNA-seq Library Preparation

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Applications | Impact on Data Quality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Template Switching Oligos (TSO) | Enables full-length cDNA synthesis by reverse transcriptase | SMART-seq2, SMART-seq3, NEBnext | Critical for full-length transcript coverage and 5' end completeness |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Molecular barcodes for counting individual mRNA molecules | 10x Genomics, Drop-Seq, MARS-seq, SMART-seq3 | Reduces amplification bias, improves quantitative accuracy |

| Barcoded Beads | Cell-specific barcoding in droplet-based methods | 10x Genomics, Drop-Seq, inDrop | Enables multiplexing of thousands of cells, determines cell recovery efficiency |

| Cell Stabilization Reagents | Preserve RNA quality before processing | Parse Evercode, 10x Genomics Flex | Maintains transcriptome integrity, especially important for clinical samples |

| RNase Inhibitors | Prevent RNA degradation during processing | All scRNA-seq protocols | Essential for preserving RNA quality, especially critical for sensitive cell types |

| M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase | cDNA synthesis from RNA templates | All scRNA-seq protocols | Efficiency impacts cDNA yield and library complexity |

| Ribo-Depletion Reagents | Remove ribosomal RNA reads | FFPE protocols, total RNA methods | Improves sequencing efficiency for mRNA-derived fragments |

| Chemical Conversion Reagents | Label newly synthesized RNA in dynamic studies | mCPBA, TFEA, iodoacetamide | Enables time-resolved analysis of RNA synthesis and degradation |

Technology Selection Framework

Diagram 2: Relationship Between Library Preparation Methods and Analytical Outcomes. This diagram illustrates how technical choices in library preparation directly influence multiple dimensions of data quality and subsequent biological interpretations.

Library preparation protocols exert a profound and systematic influence on scRNA-seq data quality and downstream analytical outcomes. The accumulating evidence from rigorous benchmarking studies demonstrates that there is no single optimal protocol for all applications—rather, the choice of method must be carefully matched to specific research objectives, sample characteristics, and analytical priorities [27] [28] [29].

For applications requiring deep transcriptional characterization of limited cell numbers, such as stem cell biology or rare cell population analysis, plate-based full-length methods like SMART-seq3 and G&T-seq provide superior gene detection sensitivity and isoform information [29]. In contrast, large-scale atlas projects and studies of highly complex tissues benefit from the high-throughput capabilities of droplet-based methods like 10x Genomics Chromium, despite their lower sensitivity per cell [27] [25]. For specialized applications including FFPE samples, clinical biomarker discovery, and time-resolved analysis, recently developed optimized protocols address specific challenges such as RNA degradation, low input material, and metabolic labeling [28] [34] [32].

As single-cell technologies continue to evolve, the framework for evaluating and selecting library preparation methods must incorporate multiple dimensions of performance including sensitivity, accuracy, throughput, cost, and operational practicality. Future developments will likely further specialize protocols for particular biological questions and sample types, while computational methods advance to correct remaining technical artifacts. Through continued rigorous benchmarking and transparent reporting of protocol performance, the scRNA-seq community can ensure that biological discoveries are built upon a foundation of robust and reproducible analytical outcomes.

Building a Robust Analysis Pipeline: A Step-by-Step Guide to Best-Performing Tools

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized biological research by enabling the characterization of gene expression at unprecedented resolution, revealing cellular heterogeneity and identifying rare cell populations that are often masked in bulk sequencing approaches [2]. However, the accuracy of these biological insights is heavily dependent on robust data quality control (QC) to address inherent technical artifacts. Two of the most critical challenges in scRNA-seq analysis are doublets (multiple cells captured within a single droplet or reaction volume) and ambient RNA (background nucleic acid contamination) [35].

Doublets can lead to spurious biological interpretations, potentially masquerading as novel cell types or intermediate states [36]. They are generally categorized as homotypic (formed by cells of the same type) or heterotypic (formed by cells of distinct types), with the latter being particularly problematic as they can create artifactual transitional populations [36] [37]. Meanwhile, ambient RNA contamination, more prevalent in single-nuclei RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq), can reduce the specificity of cell type identification by adding background noise to true cellular transcriptomes [35].

This guide provides an objective comparison of two essential tools for addressing these challenges: scDblFinder for doublet detection and CellBender for ambient RNA removal. We evaluate their performance, methodologies, and integration within benchmarking pipelines for scRNA-seq analysis.

scDblFinder: Comprehensive Doublet Identification

scDblFinder is a Bioconductor-based doublet detection method that integrates insights from previous approaches while introducing novel improvements to generate fast, flexible, and robust doublet predictions [36]. The method builds upon the observation that most computational doublet detection approaches rely on comparisons between real droplets and artificially simulated doublets.

The core methodology of scDblFinder involves several key stages [36] [38]:

- Artificial Doublet Generation: Creates simulated doublets by combining expression profiles from randomly selected cell pairs, using a mixed strategy that includes summing libraries, Poisson resampling, and re-weighting based on relative cell sizes.

- Feature Calculation: Generates a k-nearest neighbor (kNN) graph on the union of real cells and artificial doublets, gathering neighborhood statistics at various sizes to enable the classifier to select the most informative scale.

- Iterative Classification: Employs a gradient boosting classifier (XGBoost) trained on features derived from the kNN graph, with an iterative procedure that removes confidently predicted doublets from the training set in successive rounds to avoid classifier contamination.

A key advantage of scDblFinder is its flexibility in artificial doublet generation, offering both random and cluster-based approaches, with the former now set as default [38]. The method also efficiently handles multiple samples by processing them separately to account for sample-specific doublet rates, while supporting multithreading for computational efficiency [38].

CellBender: Deep Learning for Ambient RNA Removal

CellBender addresses the problem of ambient RNA contamination using a deep generative model approach. Unlike traditional background correction methods, CellBender leverages a probabilistic framework to distinguish true cell-containing droplets from empty droplets and accurately estimate the background RNA profile.

The methodological foundation of CellBender includes [35]:

- Probabilistic Modeling: Utilizes a Bayesian generative model that represents observed gene expression counts as a mixture of true cellular expression and ambient RNA contamination.

- Neural Network Implementation: Employs deep neural networks to approximate the complex posterior distributions of model parameters, enabling scalable inference on large-scale scRNA-seq datasets.

- GPU Acceleration: Implements computationally intensive operations using GPU optimization, significantly reducing processing time compared to CPU-based alternatives.

CellBender's approach specifically models the barcode rank plot to determine appropriate parameters for background removal, and has demonstrated particular effectiveness in single-nucleus RNA sequencing data where ambient RNA contamination is more pronounced [35].

Performance Benchmarking and Comparative Analysis

scDblFinder Performance Evaluation

scDblFinder has been extensively benchmarked against alternative doublet detection methods across multiple datasets. In an independent evaluation by Xi and Li, scDblFinder was found to have the best overall performance across various metrics [36] [38].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Doublet Detection Methods Across Benchmark Datasets

| Method | Mean AUPRC | Precision | Recall | Computational Efficiency | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| scDblFinder | Highest | Top performer | Top performer | Fast (multithreading support) | Best overall accuracy, handles multiple samples well |

| DoubletFinder | High | High | High | Moderate | Early top performer, kNN-based |

| scMODD | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Not specified | Model-driven approach, NB/ZINB models |

| cxds/bcds | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Fast | Co-expression based (cxds), classifier-based (bcds) |

| Scrublet | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Fast | Simulated doublets, early popular method |

The superior performance of scDblFinder is attributed to its integrated approach that combines multiple detection strategies and its adaptive neighborhood size selection, which allows it to handle varying data structures more effectively than methods relying on fixed parameters [36]. The iterative classification scheme further enhances performance by reducing false positives that could mislead the classifier in subsequent rounds.

CellBender Performance Assessment

CellBender has demonstrated significant effectiveness in removing ambient RNA contamination, particularly for challenging datasets with high background noise. Empirical tests show that CellBender can substantially improve marker gene specificity [35].

In one representative case study involving monocyte marker LYZ, CellBender removal of background RNA significantly increased the specificity of detection, enhancing the signal-to-noise ratio for downstream analysis [35]. Computational performance tests indicate that running CellBender on a typical sample takes approximately one hour with GPU acceleration, compared to over ten hours using CPU-only processing, highlighting the importance of GPU resources for practical implementation [35].

Integrated Workflow Performance

When implemented within a comprehensive QC pipeline such as scRNASequest, the combination of scDblFinder and CellBender provides complementary quality control by addressing both doublet artifacts and ambient RNA contamination [35]. This integrated approach ensures that downstream analyses including clustering, differential expression, and trajectory inference are built upon a foundation of high-quality, artifact-free data.

Experimental Protocols and Implementation Guidelines

scDblFinder Implementation

Basic Usage Protocol:

Key Parameters:

dbr: Expected doublet rate (default: 1% per 1000 cells)dbr.sd: Standard deviation of expected doublet ratesamples: Sample identifiers for multi-sample processingclusters: Whether to use cluster-based artificial doubletsBPPARAM: Multithreading parameters for parallel processing

For optimal performance, users should specify sample information when available, as this allows scDblFinder to account for sample-specific doublet rates and process samples independently, improving robustness to batch effects [38]. The expected doublet rate should be adjusted according to the capture technology and cell loading density.

CellBender Implementation

Basic Command Line Usage:

Critical Parameters:

--expected-cells: Estimated number of true cells in the dataset--total-droplets-included: Total number of droplets to include in analysis--fpr: False positive rate for background removal (default: 0.01)--epochs: Number of training epochs for the neural network

Proper parameterization requires inspection of barcode rank plots to determine the appropriate number of expected cells and total droplets [35]. For efficient processing, GPU access is strongly recommended, as CPU-only operation can be computationally prohibitive for large datasets.

Visualization of Integrated Quality Control Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated quality control workflow incorporating both scDblFinder and CellBender within a comprehensive scRNA-seq analysis pipeline:

Integrated scRNA-seq QC Workflow

This workflow demonstrates the sequential application of quality control steps, with CellBender addressing ambient RNA contamination prior to doublet detection with scDblFinder, ensuring that each step builds upon properly cleaned data from the previous stage.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Computational Tools and Resources for scRNA-seq Quality Control

| Tool/Resource | Function | Implementation | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| scDblFinder | Doublet detection | R/Bioconductor | Iterative classification, multiple sample support, cluster-aware |

| CellBender | Ambient RNA removal | Python/PyTorch | Deep learning model, GPU acceleration, probabilistic background removal |

| SingleCellExperiment | Data container | R/Bioconductor | Standardized object structure for scRNA-seq data |

| Seurat | scRNA-seq analysis | R | Comprehensive toolkit, integration with scDblFinder |

| Scanpy | scRNA-seq analysis | Python | Python-based analysis suite, compatible with CellBender output |

| Cell Ranger | Initial processing | Proprietary | 10X Genomics pipeline, generates input for CellBender |

| Harmony | Batch correction | R/Python | Integration of multiple samples, complements doublet detection |

Based on comprehensive benchmarking evidence, scDblFinder represents the current state-of-the-art in computational doublet detection, demonstrating superior performance across diverse datasets and experimental conditions [36] [38]. Its integrated approach combining multiple detection strategies, adaptive neighborhood selection, and iterative classification provides robust identification of heterotypic doublets that pose the greatest risk for spurious biological interpretations.

Similarly, CellBender offers a powerful solution for ambient RNA contamination, particularly valuable for single-nucleus RNA sequencing and datasets with significant background noise [35]. Its GPU-accelerated implementation makes it practical for large-scale studies, though adequate computational resources must be available.