Beyond Model Species: Advanced Strategies for Validating Plant Gene Function in Non-Model Organisms

Validating gene function in non-model plants is crucial for crop improvement and discovering novel biomolecules but presents unique challenges due to limited genomic resources.

Beyond Model Species: Advanced Strategies for Validating Plant Gene Function in Non-Model Organisms

Abstract

Validating gene function in non-model plants is crucial for crop improvement and discovering novel biomolecules but presents unique challenges due to limited genomic resources. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles of non-model plant genomics. It explores cutting-edge methodological pipelines like NEEDLE and EDGE, offers practical troubleshooting advice for experimental optimization, and details robust validation frameworks that integrate computational predictions with experimental evidence. By synthesizing recent advances in functional genomics, this resource aims to accelerate the reliable characterization of gene function in agriculturally and medically important plant species.

The Unique Challenges and Core Principles of Non-Model Plant Genomics

Why Non-Model Organisms? Bridging the Genomics Resource Gap in Plant Research

Model organisms like Arabidopsis thaliana have been fundamental to plant molecular biology, providing a simplified system for discovering core genetic and developmental mechanisms [1]. However, this very simplicity creates a significant knowledge gap, as these models cannot represent the vast functional diversity of the plant kingdom [2] [3]. Research into non-model organisms is crucial for understanding specialized traits—such as unique metabolic pathways, complex morphological adaptations, and specific environmental resistances—that are absent from conventional models [1] [4]. With advances in sequencing and genomic technologies, it is now increasingly feasible to bridge the genomics resource gap, moving beyond model systems to explore the full breadth of plant biology and apply these findings to crop improvement, conservation, and biotechnology [5] [2].

The Genomic Resource Gap: A Comparative Analysis

The table below summarizes the key distinctions between traditional model organisms and non-model organisms, highlighting the specific challenges and unique opportunities presented by non-model systems.

Table: Bridging the Gap Between Model and Non-Model Plant Organisms

| Aspect | Traditional Model Organisms | Non-Model Organisms | Bridging the Gap: Solutions & Technologies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Tools | Extensive, well-established (e.g., mutant libraries, standardized transformation) [1] | Limited or non-existent; protocols often require development from scratch [6] [4] | Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS), CRISPR-Cas9 [7] [2] [6] |

| Genomic Resources | Complete, high-quality reference genomes and comprehensive databases [1] [2] | Often lacking a reference genome; limited sequence data [2] [3] | De novo genome assembly, RNA-Seq for gene discovery, EST databases [5] [6] |

| Research Cycle Time | Short life cycles (e.g., Arabidopsis ~6-8 weeks) enable rapid experimentation [1] | Often long life cycles (e.g., orchids taking 2-3 years to flower) slow research progress [6] | Gene silencing vectors (e.g., CymMV-based) to study gene function in weeks, not years [6] |

| Phenotypic Novelty | Limited to the biology of the model species [4] | Enormous diversity for studying evolution, ecology, and specialized traits [1] [3] | Comparative genomics and network analyses (e.g., NEEDLE pipeline) to identify key regulators [7] |

| Community & Infrastructure | Large research communities, stock centers, and consolidated funding [2] | Smaller, more collaborative communities; lack of central stock centers [4] | Development of shared bioinformatic tools and databases tailored for non-model plants [3] |

Experimental Paradigms: From Gene Discovery to Validation

Bridging the genomics gap requires integrated workflows that combine modern computational tools with functional validation techniques adaptable to non-model species.

Computational Gene Discovery in Non-Model Plants

For species with limited genomic resources, co-expression network analysis is a powerful method to identify candidate genes regulating traits of interest. The NEEDLE (Network-Enabled gene Discovery pipeLinE) pipeline exemplifies this approach [7].

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Functional Genomics

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Application | Example in Non-Model Research |

|---|---|---|

| CymMV-Pro60 VIGS Vector | A viral vector derived from a symptomless Cymbidium mosaic virus strain used to transiently silence target genes in orchids [6]. | Enabled functional study of B- and C-class MADS-box genes in Phalaenopsis orchids, causing clear morphological changes in flowers [6]. |

| Next-Generation Sequencer (NGS) | Hardware for decoding plant DNA/RNA rapidly and accurately, generating the raw data for genome assembly or transcriptome analysis [5] [8]. | Used for whole-genome sequencing of small cardamom, generating a draft genome and identifying over 250,000 SSR markers [5]. |

| Bioinformatics Platforms | Software/cloud computing tools for analyzing, interpreting, and visualizing large-scale genetic data like sequence alignment and network analysis [7] [8]. | The NEEDLE pipeline uses such tools to build co-expression networks from transcriptome data and pinpoint upstream transcription factors [7]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | A precise genome-editing technology that can be adapted to non-model organisms once basic genomic information is available [2]. | Successfully implemented in diatoms (Thalassiosira pseudonana and Phaeodactylum tricornutum) for targeted gene knockouts [2]. |

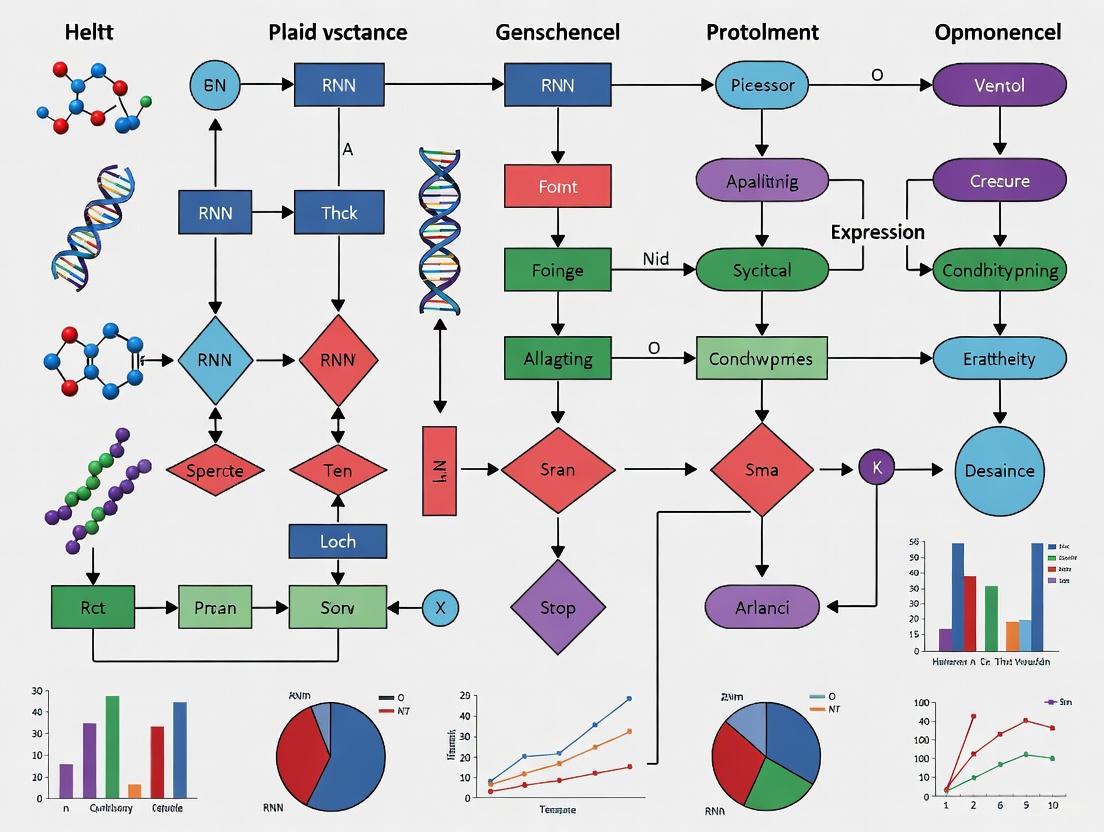

Figure 1: NEEDLE Pipeline Workflow for Gene Discovery. This network-based computational pipeline identifies key transcriptional regulators from transcriptomic data, enabling gene discovery in non-model species [7].

Functional Validation: A Case Study on Orchid Flowering Genes

Studying the molecular basis of floral morphology in orchids is a prime example of overcoming a long life cycle (2-3 years to flower) through adapted functional genomics tools [6]. The following protocol details the use of Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS).

Experimental Protocol: VIGS for Functional Gene Validation in Orchids [6]

Vector Construction:

- Isolate a mild, symptomless strain of Cymbidium mosaic virus (CymMV).

- Engineer an infectious cDNA clone (e.g., pCymMV-M1) containing a T3 promoter and a poly(A) tail.

- Create the VIGS vector (e.g., pCymMV-pro60) by duplicating the viral coat protein (CP) subgenomic promoter to drive the expression of inserted target gene fragments.

Insert Preparation and Cloning:

- Amplify a unique, non-conserved fragment (e.g., 150 nucleotides) of the target gene (e.g., the MADS-box gene PeMADS6) from orchid cDNA.

- Critical Note: Using a short, unique fragment ensures specific gene silencing. Using a longer, conserved fragment (e.g., 500 nt) can lead to the simultaneous silencing of multiple members of the same gene family.

- Clone the target gene fragment into the pCymMV-pro60 vector.

Plant Inoculation:

- In vitro transcribe the recombinant plasmid to create infectious RNA transcripts.

- Mechanically inoculate the transcripts onto the leaves of young Phalaenopsis plants.

Monitoring and Analysis:

- Allow 2-4 weeks for the virus to establish systemic infection and induce silencing.

- Monitor plants for viral infection (e.g., via northern blot) and silencing efficacy.

- Quantify the knockdown of the target gene mRNA using real-time RT-PCR.

- Document phenotypic consequences (e.g., altered floral organ identity and morphology) in developing flowers.

Figure 2: VIGS Experimental Workflow. This method allows for rapid functional analysis of genes in non-model plants with long life cycles, such as orchids [6].

The strategic study of non-model organisms is not a niche pursuit but an essential pathway to a comprehensive understanding of plant biology. As genomic technologies continue to become more accessible and powerful, the resource gap that once made such research prohibitive is rapidly closing [5] [2] [8]. The integration of de novo sequencing, advanced bioinformatics, and adaptable functional tools like VIGS and CRISPR is democratizing functional genomics. By embracing the immense diversity of non-model plants, researchers can uncover novel genetic mechanisms, accelerate crop improvement, and ultimately address pressing global challenges in food security and environmental sustainability [5] [3].

For researchers studying non-model plant organisms, the scarcity of comprehensive multi-omics resources presents a significant bottleneck in gene discovery and functional validation. This guide compares two predominant strategy types—computational inference pipelines and targeted experimental validation methods—that enable initial gene discovery without relying on extensive pre-existing multi-omics datasets. Performance comparisons, based on experimental data from recent studies, highlight the contexts in which each strategy excels, providing a framework for scientists to select the optimal approach for their research goals and resource constraints.

Non-model plants, which constitute the vast majority of horticultural and crop species, lack the extensive multi-omics datasets and well-characterized genetic tools available for model organisms like Arabidopsis thaliana [9] [10]. This scarcity impedes the identification of key transcriptional regulators and functional genes controlling agronomically important traits. Traditional genetic transformation methods remain inefficient, costly, and heavily dependent on tissue culture, which is unavailable for many species [10]. Furthermore, genomic annotations for non-model organisms often contain persistent errors, such as chimeric gene mis-annotations, which complicate downstream analysis and functional validation [11]. This guide objectively evaluates and compares emerging strategies designed to overcome these limitations, enabling effective initial gene discovery with minimal multi-omics data requirements.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Gene Discovery Strategies

The table below summarizes the core performance metrics of two complementary strategies for initial gene discovery in non-model plants, based on recent experimental validations.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Gene Discovery Strategies for Non-Model Plants

| Strategy | Key Methodology | Validated Organisms | Transformation Efficiency | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEEDLE Pipeline [7] | Network-based analysis of dynamic transcriptome data to infer upstream regulators. | Maize, Soybean, Brachypodium, Sorghum | Not Applicable (Computational) | Identifies key Transcription Factors (TFs) without prior multi-omics data; Rapid in planta validation; User-friendly. | Relies on availability of dynamic transcriptome datasets. |

| Non-Tissue Culture Transformation [10] | A. rhizogenes-mediated root transformation; Virus-mediated genome editing (e.g., TRV, CLBV). | Strawberry, Citrus, Tobacco (N. benthamiana) | Successful root transformation in strawberry and citrus; Efficient Pds gene editing in tobacco. | Bypasses complex tissue culture; Cost-effective and less time-consuming; Applicable to species resistant to tissue culture. | Primarily generates chimeric or non-germline edits; Limited to certain species/varieties. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Workflows

NEEDLE Computational Pipeline Methodology

The NEEDLE (Network-Enabled gene Discovery pipeline) provides a systematic, network-based approach to identify key transcriptional regulators from dynamic transcriptome data, which is particularly valuable when other omics datasets are unavailable [7].

Experimental Protocol:

- Data Input: Collect RNA-seq data from a time-course experiment or multiple conditions relevant to the trait of interest (e.g., stress response, development).

- Network Module Generation: The pipeline systematically generates co-expression gene network modules from the dynamic transcriptome data.

- Connectivity and Hierarchy Analysis: NEEDLE measures gene connectivity within the network and establishes a network hierarchy to pinpoint key transcriptional regulators upstream of genes of interest.

- Validation: Candidates are rapidly validated in planta using techniques such as CRISPR/Cas9 or transient expression assays [7].

Workflow Diagram: NEEDLE Gene Discovery Pipeline

Non-Tissue Culture Transformation & Validation Methods

For functional validation of candidate genes in non-model plants, several methods bypass the need for inefficient and complex tissue culture systems.

A. Agrobacterium rhizogenes-Mediated Hairy Root Transformation [10] This method allows for rapid functional analysis of genes in root tissues.

Experimental Protocol:

- Strain Preparation: Culture A. rhizogenes (e.g., K599 strain) carrying the binary plasmid with the gene of interest (e.g., GFP reporter or genome editing components) until OD₆₀₀ reaches 1.0.

- Centrifugation and Resuspension: Pellet bacteria and resuspend in an infiltration solution.

- Plant Infiltration: Infiltrate the bacterial suspension into plant tissues (e.g., stems of citrus or strawberry).

- Hairy Root Induction: Transfer treated plants to vermiculite for rooting. Transformed hairy roots, exhibiting typical morphology, can be observed within several weeks.

- Confocal Microscopy: Analyze transformed roots using laser scanning confocal microscopy (e.g., excitation 488 nm, emission 505–550 nm for GFP) [10].

B. Virus-Mediated Genome Editing [10] This approach utilizes viruses to deliver genome editing components into plants that already express Cas9.

Experimental Protocol:

- Plant Material: Use Cas9-overexpressing transgenic plants (e.g., tobacco).

- Virus Vector Preparation: Engineer virus vectors (e.g., Tobacco Rattle Virus - TRV, or Citrus Leaf Blotch Virus - CLBV) to carry the gRNA module targeting an endogenous gene (e.g., Pds).

- Plant Infection: Infect the Cas9-expressing plants with the engineered virus.

- Phenotype Analysis: Successful editing is confirmed by observing the expected phenotype (e.g., photo-bleaching in case of Pds knockout) [10].

Workflow Diagram: Non-Tissue Culture Validation Methods

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Non-Model Plant Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Agrobacterium rhizogenes (K599) | Mediates genetic transformation of roots to produce "hairy roots" for rapid gene functional analysis. | Functional gene analysis in strawberry and citrus roots [10]. |

| Virus Vectors (TRV, CLBV) | Delivery system for genome editing components (gRNA) into Cas9-expressing plants. | Editing the endogenous Pds gene in tobacco [10]. |

| Developmental Regulators (DRs) | Genes that enhance shoot and root formation, facilitating in planta transformation. | Inducing transgenic shoot formation in plants resistant to traditional transformation [10]. |

| Machine Learning Annotation Tools (Helixer) | Improves gene model accuracy and identifies mis-annotations like chimeric genes in novel genomes. | Validating and correcting gene models in non-model plant genomes [11]. |

Critical Consideration: Addressing Annotation Quality

A foundational challenge in non-model organism research is the prevalence of chimeric gene mis-annotations, where distinct adjacent genes are incorrectly fused. A 2025 study identified 605 such confirmed cases across 30 eukaryotic genomes, with plants and invertebrates being particularly affected [11]. These errors propagate through databases and can severely mislead gene discovery efforts, resulting in incorrect functional assignments and expression profiles. Utilizing modern annotation tools like Helixer, a deep learning-based model, can help identify and correct these errors, thereby increasing the reliability of the genomic data used for discovery pipelines like NEEDLE [11].

For researchers embarking on gene discovery in non-model plants with limited multi-omics data, the choice of strategy depends on the specific research question and available resources.

- For Prioritizing Key Regulators: The NEEDLE computational pipeline is highly effective when transcriptome data from dynamic processes (e.g., development, stress response) is available. Its ability to infer upstream regulators from co-expression networks makes it a powerful, cost-effective first step [7].

- For Functional Gene Validation: Non-tissue culture transformation methods are indispensable for bypassing the major bottleneck of tissue culture. A. rhizogenes-mediated transformation and virus-mediated editing provide rapid, feasible avenues for in planta functional validation in many recalcitrant species [10].

- For Ensuring Data Foundation: Regardless of the chosen path, initial investment in validating and improving genome annotation quality using tools like Helixer is crucial to prevent downstream failures caused by mis-annotated genes [11].

By integrating robust computational inference with direct experimental validation techniques, researchers can systematically overcome the initial barrier of limited multi-omics datasets and accelerate the discovery and functional characterization of genes in non-model plants.

Leveraging Evolutionary Conservation and Divergence in Gene Regulatory Networks

Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs) represent the complex circuits of interactions between transcription factors (TFs) and their target genes, governing cellular processes, organismal development, and stress responses. For researchers studying non-model plant organisms—species lacking extensive genomic resources or genetic tools—GRN analysis provides a powerful framework for inferring gene function by leveraging evolutionary principles. The central premise is that functional conservation preserves core regulatory modules across species, while evolutionary divergence creates species-specific adaptations. This duality enables scientists to extrapolate knowledge from model organisms while identifying unique biological mechanisms in their species of interest. Understanding both conserved and divergent elements has become particularly valuable for crop improvement, as it allows researchers to identify key regulators of traits that may have been lost in model systems but preserved in non-model crops or wild relatives.

Recent advances in comparative genomics and single-cell technologies have revolutionized our ability to map GRNs across species, even with limited prior genomic information. These approaches rely on the fundamental discovery that while trans-regulatory components (transcription factors themselves) often remain conserved across evolutionary timescales, cis-regulatory elements (promoters, enhancers) diverge more rapidly, creating species-specific gene expression patterns [12] [13]. This evolutionary principle enables researchers to distinguish between core biological processes essential across species and specialized adaptations unique to particular organisms or environments.

Theoretical Foundations: Evolutionary Principles of GRN Architecture

The Conservation-Divergence Spectrum in Gene Regulation

Gene regulatory networks evolve through a dynamic interplay between conservation of core circuits and divergence of peripheral components. Studies comparing salt stress responses in the early-diverging plant Marchantia polymorpha and the late-diverging Arabidopsis thaliana revealed that WRKY-family transcription factors and their feedback loops serve as central nodes in salt-responsive GRNs across evolutionary timescales [12]. Despite this conservation in trans-regulatory components, the cis-regulatory sequences of WRKY-target genes showed significant divergence, associated with network expansion and specialization [12].

This pattern of conserved trans-regulators and quickly evolving cis-regulatory sequences appears to be a fundamental principle across kingdoms. Research in mammalian systems demonstrated that the genomic regulatory syntax—the DNA motifs recognized by sequence-specific DNA binding proteins—remains highly conserved from rodents to primates, despite substantial sequence divergence in regulatory elements [13]. This conservation enables the prediction of regulatory elements in non-model species based on known motifs from model organisms.

Mechanisms of GRN Rewiring and Functional Consequences

GRN evolution occurs through several mechanistic pathways:

Regulatory Element Turnover: Enhancers and other regulatory elements exhibit rapid turnover during evolution, with transposable elements contributing significantly to species-specific regulatory innovation [13]. In fact, studies of the mammalian neocortex found that transposable elements contribute to nearly 80% of human-specific candidate cis-regulatory elements in cortical cells [13].

Network Rewiring: Changes in the connections between transcription factors and their target genes can lead to phenotypic divergence. Comparative studies between humans and mice revealed that rewired regulatory relationships contain a higher proportion of species-specific regulatory elements and can alter functional modules composed of many regulatory targets [14].

Expression Domain Shifts: Conservation of protein-coding sequences with divergence in expression patterns can lead to novel traits. For example, a chromosomal inversion of chromosome 12 in the neem lineage (Azadirachta indica) compared to chinaberry (Melia azedarach) represents a karyotypic change underlying allopatric speciation, potentially affecting gene regulation [15].

Table 1: Evolutionary Mechanisms Driving GRN Conservation and Divergence

| Mechanism | Impact on GRN | Evolutionary Timescale | Functional Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trans-factor Conservation | Preservation of core network architecture | Long-term conservation | Maintenance of essential biological processes |

| Cis-element Divergence | Alteration of regulatory connections | Rapid evolution | Species-specific expression patterns and adaptations |

| Network Rewiring | Changes in TF-target gene relationships | Medium to long-term | Phenotypic differences between species |

| Regulatory Element Turnover | Gain/loss of regulatory elements | Rapid evolution | Regulatory innovation and specialization |

| Gene Family Expansion | Increase in network components | Variable | Specialized metabolic pathways or physiological adaptations |

Computational Approaches for Comparative GRN Analysis

Network Construction and Comparison Methodologies

Computational tools for GRN comparison leverage evolutionary principles to identify both conserved and divergent regulatory elements. The sc-compReg method enables comparative analysis of GRNs between conditions or species using single-cell data through a multi-step process [16]:

Joint Clustering and Embedding: Cells from both scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq data are jointly clustered and visualized in a unified embedding, allowing identification of homologous cell types across species.

Linked Subpopulation Identification: Corresponding cell populations across species or conditions are matched based on conserved marker gene expression, ensuring that comparisons are made between biologically equivalent cell types.

Differential Regulatory Analysis: A novel statistical test identifies differential regulatory relations between linked subpopulations based on changes in the relationship between transcription factor regulatory potential (TFRP) and target gene expression.

The NEEDLE (Network-Enabled Gene Discovery) pipeline addresses the challenge of limited multi-omics resources for non-model species by systematically generating co-expression gene network modules, measuring gene connectivity, and establishing network hierarchy to pinpoint key transcriptional regulators from dynamic transcriptome datasets [7]. This approach has been successfully applied to identify transcription factors regulating cellulose synthase-like F6 (CSLF6) in Brachypodium and sorghum, revealing both evolutionarily conserved and divergent regulatory elements among grass species [7].

For visual comparison of multiple networks, CompNet provides a graphical user interface that allows researchers to identify union, intersection, and exclusive regions across networks, with visualization features like "pie-nodes" that display node affiliation across multiple networks simultaneously [17].

Quantitative Metrics for GRN Comparison

Several specialized metrics enable quantitative comparison of GRNs across species:

CompNet Neighbor Similarity Index (CNSI): A novel metric for capturing neighborhood architecture of constituent nodes, going beyond simple edge comparison to account for local network topology [17].

Transcription Factor Regulatory Potential (TFRP): A cell-specific index that integrates TF expression and regulatory potential calculated from accessibility of multiple regulatory elements, providing a more comprehensive view of regulatory relationships than TF expression alone [16].

Phenotype Similarity (PS) Score: A quantitative measure of phenotypic similarity of orthologous genes between species, allowing correlation of network rewiring with phenotypic outcomes [14].

Table 2: Computational Tools for GRN Construction and Comparison

| Tool | Primary Function | Data Input Requirements | Key Features | Applicability to Non-Model Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEEDLE | Network-based gene discovery | Dynamic transcriptome data | Identifies upstream transcriptional regulators without full genome sequence | High - designed specifically for non-model species |

| sc-compReg | Comparative regulatory analysis | scRNA-seq + scATAC-seq from two conditions | Tests differential regulatory relations; controls false discovery rate | Medium - requires single-cell data which may be limited |

| CompNet | Visual network comparison | Edge-lists, node-lists, or path-lists | GUI-based; "pie-node" visualization; union/intersection analysis | High - works with various network input formats |

| Regulatory Network Repository (RegNetwork) | TF-target gene relationships | Experimental or predicted regulatory connections | Integrated data of regulatory connections; cross-species comparisons | Medium - depends on available regulatory data for species of interest |

Figure 1: Computational workflow for comparative GRN analysis in non-model plant species, integrating multiple data types and analytical steps to identify evolutionarily conserved and divergent regulatory elements.

Experimental Protocols for GRN Validation in Non-Model Plants

Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) for Functional Validation

For non-model plants with large genomes, low transformation efficiency, and long regeneration times, Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) provides an efficient alternative to stable transformation for validating GRN components [6]. The protocol using Cymbidium mosaic virus (CymMV)-based vectors for orchids exemplifies this approach:

Vector Construction:

- Isolate a mild, symptomless CymMV strain from Phalaenopsis species to minimize physiological changes that could complicate interpretations.

- Engineer the pCymMV-pro60 vector with duplicated subgenomic promoter of coat protein (CP) to enhance foreign RNA transcription [6].

- Clone target gene fragments (150-500 nt) into the vector, with shorter fragments providing greater gene specificity and longer fragments potentially targeting multiple gene family members.

Plant Inoculation and Validation:

- In vitro transcribe recombinant vectors and mechanically inoculate leaves of target plants.

- Monitor systemic infection 14-28 days post-inoculation using northern blot analysis to confirm viral spread.

- Quantify target gene knockdown using real-time RT-PCR, typically achieving 73-97.8% reduction in transcript levels depending on fragment length and specificity [6].

- Document morphological phenotypes, with floral identity gene silencing in orchids producing visible changes in flower morphology within 2 months compared to 2-3 years for conventional approaches.

This methodology dramatically accelerates functional validation in slow-growing species, enabling researchers to test predictions from comparative GRN analyses without establishing stable transformation protocols.

Integrative Multi-Omics Validation Framework

For comprehensive validation of conserved and divergent GRN components, an integrated multi-omics approach provides the most robust evidence:

Cross-Species Epigenomic Profiling: Generate comparative chromatin accessibility maps (ATAC-seq), DNA methylomes, and chromatin conformation data for homologous tissues across multiple species [13].

Expression Quantitative Trait Loci (eQTL) Mapping: Identify genetic variants associated with expression changes, particularly focusing on trans-eQTLs that indicate changes in regulatory relationships [14].

Machine Learning-Based Prediction: Train sequence-based predictors of candidate cis-regulatory elements in different species, leveraging the conserved genomic regulatory syntax to identify functional elements [13].

Phenotypic Correlation: Associate network features with phenotypic differences using semantic phenotyping approaches like PhenoDigm, which enables quantitative comparison of phenotypic similarity across species [14].

Case Studies: Evolutionary Insights from Comparative GRN Analysis

Salt Stress Response Across Plant Evolution

A landmark study comparing salt-responsive GRNs in Marchantia polymorpha (early-diverging plant) and Arabidopsis thaliana (late-diverging plant) revealed both deeply conserved and rapidly evolving elements [12]. The research demonstrated:

Conserved Components: WRKY transcription factors maintained central positions in both networks, with conserved feedback loops despite ~450 million years of divergence.

Divergent Elements: Cis-regulatory sequences showed significant divergence, with network size expansion in Arabidopsis linking salt stress to more specialized developmental and physiological responses.

Evolutionary Pattern: The conserved trans-regulators with quickly evolving cis-regulatory sequences represent a strategic balance maintaining core functions while allowing environmental adaptation.

This comparative approach explained how stress response networks can maintain essential functions while acquiring species-specific adaptations, providing a template for engineering stress resilience in crops by manipulating recently evolved network components.

Limonoid Biosynthesis in Meliaceae Species

Comparative genomics of neem (Azadirachta indica) and chinaberry (Melia azedarach) revealed how regulatory evolution contributes to biochemical diversity [15]. The study identified:

Speciation Mechanism: A lineage-specific inversion of chromosome 12 in the neem lineage contributed to allopatric speciation, potentially affecting gene regulation.

Enzyme Diversification: Two BAHD-acetyltransferases in chinaberry (MaAT8824 and MaAT1704) catalyze acetylation at both C-12 and C-3 hydroxyl groups of limonoids, while the syntenic neem copy (AiAT0635) lacks this activity.

Functional Restoration: A critical N-terminal region (SAGAVP) was identified that could restore acetylation activity when swapped into the chinaberry enzyme, demonstrating how minimal changes can create functional diversity.

This case illustrates how comparative analysis of specialized metabolism GRNs can identify key genetic changes underlying chemical diversity, with applications for metabolic engineering of valuable plant compounds.

Table 3: Experimental Approaches for GRN Validation in Non-Model Plants

| Method | Key Applications | Timeframe | Technical Barriers | Information Gained |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) | Gene function validation; Network perturbation | 1-3 months | Virus host range; Fragment optimization | Necessary function of network components |

| Heterologous Expression | Testing regulatory function; Enzyme activity | 2-6 months | Proper protein folding; Cofactor requirements | Sufficient function of regulators |

| Comparative Epigenomics | cis-regulatory element identification; Conservation assessment | 3-6 months | Tissue homogeneity; Reference genome quality | Evolutionary conservation of regulatory elements |

| Network Perturbation Analysis | Testing network robustness; Identifying key nodes | 6-12 months | Multiple simultaneous perturbations; Phenotypic readouts | Network topology and resilience |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Essential reagents and computational resources for comparative GRN analysis in non-model plants include both experimental and bioinformatic tools:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Comparative GRN Analysis

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Considerations for Non-Model Species |

|---|---|---|---|

| VIGS Vectors | CymMV-based vectors [6]; TRV-based systems | Rapid gene silencing without stable transformation | Host range limitations; Efficiency optimization |

| Epigenomic Profiling Kits | ATAC-seq kits; ChIP-seq reagents | Mapping open chromatin; TF binding sites | Cross-species antibody compatibility; Protocol adaptation |

| Single-Cell Platforms | 10x Multiome; snm3C-seq [13] | Parallel transcriptome and epigenome profiling | Tissue dissociation protocols; Nuclei isolation |

| Comparative Genomics Databases | RegNetwork [14]; PLAZA; Phytozome | Orthology inference; Regulatory data | Taxonomic coverage; Annotation quality |

| Network Analysis Tools | NEEDLE [7]; sc-compReg [16]; CompNet [17] | Network construction; Comparative analysis | Input data requirements; Computational expertise |

Implementation Framework for Non-Model Species Research

Strategic Approach for Limited-Genomic-Resource Species

For researchers working with species having limited genomic resources, a phased implementation strategy maximizes success:

Transcriptome-First Approach: Begin with comparative transcriptomics across multiple species and conditions to identify conserved co-expression modules, using tools like NEEDLE [7]. This requires minimal genomic resources while providing substantial functional insights.

Leverage Evolutionary Conservation: Use conserved regulatory syntax and motif information from model species to predict regulatory elements in non-model species, as demonstrated by the successful prediction of cis-regulatory elements across mammals [13].

Targeted Epigenomic Profiling: Focus epigenomic analyses on genomic regions identified through comparative approaches, minimizing resource requirements while maximizing biological insights.

Functional Validation Prioritization: Prioritize candidate genes for experimental validation based on both conservation (indicating essential function) and divergence (indicating species-specific adaptations), using efficient methods like VIGS [6].

Figure 2: Implementation framework for comparative GRN analysis in non-model plant species, showing a phased approach from data collection through functional validation to practical application.

Interpretation Guidelines for Evolutionary Conservation Patterns

Correct interpretation of conservation and divergence patterns is essential for accurate functional inferences:

Deep Conservation: Network components conserved across large evolutionary distances (e.g., WRKY regulators in plant stress responses [12]) typically represent core biological processes essential for viability.

Clade-Specific Conservation: Elements conserved within a clade (e.g., primates [13]) but not outside often represent specialized biological functions important for that lineage.

Recent Divergence: Species-specific network components frequently underlie distinctive phenotypic traits, such as the specialized metabolism differences between neem and chinaberry [15].

Conserved Syntax with Divergent Elements: The preservation of DNA binding motifs with turnover of specific regulatory elements enables both network stability and flexibility [13].

The strategic analysis of evolutionary conservation and divergence in Gene Regulatory Networks provides a powerful framework for functional gene validation in non-model plant species. By leveraging the fundamental principle that core network architecture is preserved while peripheral components diverge, researchers can prioritize candidate genes for functional studies, design appropriate validation experiments, and interpret results in an evolutionary context. The integration of computational approaches like NEEDLE [7] and sc-compReg [16] with efficient experimental methods like VIGS [6] creates a feasible pathway for comprehensive gene function analysis even in species with limited genomic resources. As comparative genomics and single-cell technologies continue to advance, our ability to decipher the evolutionary language of gene regulation will increasingly enable precise manipulation of desirable traits in non-model crops, wild relatives, and specialized medicinal plants, expanding the toolbox for plant improvement and natural product discovery.

Functional genomics studies of non-model organisms, particularly plants, are crucial for understanding genetic diversity and harnessing valuable agronomic traits. However, such research faces significant challenges, including large genome sizes, lack of decoded genome information, and difficulties in gene function validation. De novo annotation tools have emerged as essential resources for assigning potential biological functions to novel transcripts assembled from high-throughput sequencing data, thereby enabling downstream functional studies. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of current bioinformatics tools for de novo annotation, with a specific focus on applications in non-model plant organism research, experimental validation methodologies, and practical implementation workflows.

Comparative Analysis of De Novo Annotation Tools

The landscape of de novo annotation tools encompasses both general-purpose platforms and specialized solutions tailored to specific biological questions. The table below summarizes the key features and applications of major tools used in plant genomics research.

Table 1: Comparison of De Novo Annotation Tools for Plant Genomics

| Tool Name | Primary Application | Key Features | Input Data | Strengths | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FunctionAnnotator | General transcriptome annotation | GO term assignment, enzyme annotation, domain identification, subcellular localization prediction | Assembled transcriptomes | Comprehensive annotations, parallel computing, taxonomic distribution | [18] |

| Oatk | Plant organelle genome assembly | Syncmer-based assembler, profile-HMM database, graph resolution algorithm | Whole-genome sequencing data | Efficient handling of complex repeats, improved over existing methods | [19] |

| NLR-Annotator | NLR immune receptor annotation | Identifies NB-ARC domains, searches for additional NLR-associated motifs | Genomic sequences | High sensitivity and specificity for NLR genes across plant taxa | [20] |

| EDTA (Extensive de-novo TE Annotator) | Transposable element annotation | Integrates multiple TE detection programs, filters false discoveries | Genome assemblies | Generates high-quality non-redundant TE libraries, benchmarks performance | [21] |

| NEEDLE | Network-based gene discovery | Generates co-expression modules, measures connectivity, establishes hierarchy | Dynamic transcriptome datasets | Identifies upstream transcription factors without multi-omics data | [7] |

Performance Metrics and Experimental Data

FunctionAnnotator demonstrates robust performance in annotating transcriptomes from non-model organisms. In a benchmark study using clam (Meretrix meretrix) transcriptome data totaling 38 Mb, FunctionAnnotator completed comprehensive annotations within 7.5 hours, identifying molecular functions for 35,971 out of 56,263 contigs. The tool successfully identified that the most abundant molecular functions were ion binding, hydrolase activity, nucleotide binding, protein binding, transferase activity, and nucleic acid binding, consistent with previous studies in marine organisms [18].

Oatk shows significant improvements in assembly quality and efficiency for plant organelle genomes. When applied to 195 land plant species, Oatk achieved more than 99.8% representation of BUSCO genes on average, with 86% represented by three complete copies, outperforming previous gene projection methods [19].

NLR-Annotator was successfully validated on the Arabidopsis genome, demonstrating both high sensitivity (ratio of identified NLR genes to all NLR genes) and specificity (ratio of correctly identified NLRs to all identified NLRs). The tool has been applied to eight economically important crops, including soybean, maize, and Brachypodium, showing broad applicability across diverse plant taxa [20].

Experimental Protocols for Annotation Validation

De Novo Annotation Workflow for Non-Model Plants

Graphviz Diagram: De Novo Annotation Workflow

Diagram Title: Comprehensive De Novo Annotation Workflow

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Transcriptome Annotation Using FunctionAnnotator

Input Preparation: Prepare assembled transcript contigs in FASTA format. FunctionAnnotator requires transcripts with predicted amino acid sequences longer than 66 amino acids for optimal annotation [18].

Annotation Execution:

- Upload transcript sequences to the FunctionAnnotator web server or run locally

- The tool performs BLAST searches against NCBI NR database

- Parallel computing enables efficient processing of large datasets

- Taxonomic distribution analysis identifies species of best hits

Output Analysis:

- GO term assignments at user-selectable levels

- Enzyme commission (EC) number annotations

- Protein domain and motif identifications

- Predictions for subcellular localization, transmembrane domains, and secretory signals

Validation Integration: Use annotation results to select candidate genes for experimental validation, prioritizing those with domains of interest but without NR database hits, as these may represent novel genes [18].

Protocol 2: NLR Gene Identification in Crop Genomes

Genome Processing: Fragment genome into 20-kb segments with short overlaps [20]

Motif Screening:

- Translate fragments in all six reading frames

- Screen for NB-ARC associated motifs

- Merge targeted fragments

Domain Extension: Use NB-ARC motifs as seeds to search upstream and downstream sequences for additional NLR-associated domains (coiled-coil, LRR)

Repertoire Assembly: Combine all reported NLR loci to generate complete NLR repertoire for the genome

This method has been successfully applied to the bread wheat genome, identifying 3,400 NLR loci and 1,560 complete NLRs, with findings of telomeric distribution and clustering providing evolutionary insights [20].

Protocol 3: Pan-Genome Annotation for Comparative Analysis

Recent advances in de novo annotation enable construction of pan-genomes for comparative analysis. A study on hexaploid wheat generated de novo gene annotations for nine cultivars, identifying 140,178 to 145,065 high-confidence gene models per cultivar. The protocol includes:

Evidence Integration: Combine Iso-Seq data (390-700K reads per sample) with RNA-seq data (56-85M read pairs per sample) across multiple tissues [22]

Gene Prediction: Utilize automated annotation pipelines incorporating transcriptomic evidence, protein homology, and ab initio prediction

Consolidation: Implement gene consolidation procedures to correct for missed gene models and ensure comparability between genomes

Orthogroup Analysis: Identify groups of orthologous genes to define core (62.52%), shell (36.61%), and cloud (0.86%) genomes across cultivars [22]

Functional Classification Systems and Database Comparisons

The effectiveness of annotation tools depends significantly on the underlying functional classification systems they utilize. Major systems include:

Table 2: Comparison of Functional Classification Systems

| System | Type | Coverage | Strengths | Applications | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eggNOG | Orthologous groups | 7.5M sequences, 30,955 leaves | Low redundancy, clean structure | General-purpose annotation | [23] |

| KEGG | Pathways | 13.2M sequences, 55,124 leaves | Manually curated, metabolic pathways | Pathway analysis, metabolism | [23] |

| InterPro:BP | Protein families | 14.8M sequences, 9,581 leaves | Comprehensive family coverage | Protein domain analysis | [23] |

| SEED | Subsystems | 47.7M sequences, 823 leaves | Clean hierarchy, process-oriented | Microbial annotation, MG-RAST | [23] |

Studies comparing these systems have found that eggNOG performs best regarding sequence redundancy and structure, while KEGG and InterPro:BP may be more informative for specific applications such as medical research [23].

Functional Validation Strategies for Non-Model Plants

Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) Protocol

For non-model plants with long life cycles, such as orchids (2-3 years to flowering), VIGS provides an efficient alternative to stable transformation for functional validation [6].

Vector Development:

- Select symptomless virus isolates (e.g., Cymbidium mosaic virus for orchids)

- Construct cDNA infectious clones with duplicated subgenomic promoters

- Insert target gene fragments (150-500 nucleotides) into viral vectors

Plant Inoculation:

- In vitro transcription to generate viral RNA

- Mechanical inoculation of transcripts onto plants

- Systemic infection established within 3-4 weeks

Efficiency Assessment:

- Quantify target gene knockdown using real-time RT-PCR

- Successful implementations achieved 73-97.8% reduction in transcription levels

- Observe morphological changes in silenced plants

This approach has been successfully used to validate functions of MADS-box genes involved in floral development in Phalaenopsis orchids, significantly accelerating functional studies in these long-lifecycle plants [6].

Network-Based Discovery Using NEEDLE

The NEEDLE pipeline enables identification of transcription factors regulating genes of interest in non-model species:

Network Construction: Generate co-expression gene network modules from dynamic transcriptome datasets [7]

Connectivity Analysis: Measure gene connectivity and establish network hierarchy to pinpoint key transcriptional regulators

Validation Application: This approach has been successfully applied to identify transcription factors regulating cellulose synthase-like F6 (CSLF6) in Brachypodium and sorghum, revealing evolutionarily conserved and divergent regulatory elements [7]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for De Novo Annotation and Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples | Specification Guidelines |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA-Seq Libraries | Transcriptome profiling | De novo assembly, expression analysis | 150 bp paired-end, 56-85M read pairs per sample [22] |

| Iso-Seq Data | Full-length transcript validation | Gene model correction, isoform discovery | 390-700K reads per sample [22] |

| CymMV VIGS Vectors | Gene silencing in orchids | Functional validation of floral genes | Symptomless isolate, duplicated subgenomic promoters [6] |

| Curated TE Library | Training data for annotation | Improving TE annotation quality | Species-specific, manually curated sequences [21] |

| HMM Profile Databases | Organelle gene identification | Plastid and mitochondrial genome assembly | 130 plastid and 81 mitochondrial gene profiles [19] |

| BUSCO datasets | Annotation quality assessment | Benchmarking completeness | poales_odb10 (4,896 genes) for Poales [22] |

De novo annotation tools have dramatically advanced functional genomics research in non-model plant organisms. FunctionAnnotator provides comprehensive transcriptome annotation capabilities, while specialized tools like NLR-Annotator and EDTA address specific biological questions. The integration of these computational tools with experimental validation methods such as VIGS enables researchers to overcome challenges associated with non-model organisms, including large genomes, long life cycles, and limited genomic resources. As demonstrated in pan-genome studies of hexaploid wheat, these approaches are revealing unprecedented insights into genetic diversity, gene family evolution, and regulatory networks, ultimately accelerating crop improvement through targeted engineering and breeding approaches.

Cutting-Edge Pipelines and Practical Workflows for Functional Validation

The functional validation of genes in non-model plant species presents a significant challenge for researchers, primarily due to the lack of comprehensive multi-omics resources that are readily available for model organisms. Identifying key transcriptional regulators of important agronomic traits represents a crucial step in developing more productive and stress-resistant crops. In this context, gene regulatory network (GRN) analysis has emerged as a powerful computational approach for deciphering the complex interactions between DNA, RNA, and proteins within plant cells. Traditionally, accurately predicting transcription factors (TFs) has been difficult due to these complex interactions and insufficient datasets for most crop species.

To address this methodological gap, researchers have developed NEEDLE (Network-Enabled Pipeline for Gene Discovery and Validation), a user-friendly tool that systematically generates co-expression gene network modules from dynamic transcriptome datasets. This pipeline measures gene connectivity and establishes network hierarchy to pinpoint key transcriptional regulators, providing plant scientists without extensive bioinformatics expertise a valuable resource for gene discovery. The applicability of NEEDLE extends to foundational research areas including photosynthetic efficiency, stress responses, and metabolic pathways in photosynthetic organisms, offering particular promise for understanding how regulatory networks evolve across species.

The NEEDLE Pipeline: Architecture and Implementation

Core Computational Methodology

The NEEDLE pipeline employs a systematic approach to transform raw transcriptomic data into biologically meaningful predictions of transcriptional regulators. Its architecture integrates co-expression network analysis with GRN prediction specifically optimized for non-model plant species. The process begins by constructing co-expression modules from dynamic transcriptome data, which involves calculating correlation coefficients between gene expression patterns across different conditions, treatments, or time points. These correlated genes are then grouped into modules that potentially represent functionally related biological processes.

Following module construction, NEEDLE employs sophisticated algorithms to measure gene connectivity within and between modules, calculating metrics such as degree centrality and betweenness centrality to identify highly connected "hub" genes. The pipeline then applies hierarchical analysis to position these hub genes within the broader network architecture, enabling the systematic identification of transcription factors that sit atop regulatory hierarchies. This integrated approach allows researchers to move from gene expression data to candidate regulator identification without requiring extensive multi-omics datasets, making it particularly valuable for species with limited genomic resources.

Experimental Validation Framework

A critical component of the NEEDLE pipeline is its integration with experimental validation methodologies. After computational identification of potential transcription factor regulators, the pipeline supports downstream validation through in planta techniques. In the referenced research, NEEDLE was applied to identify transcription factors regulating cellulose synthase-like F6 (CSLF6), a crucial cell wall biosynthetic gene, in both Brachypodium and sorghum. The validation experiments not only confirmed regulators of CSLF6 but also provided insights into the evolutionary conservation or divergence of gene regulatory elements among grass species.

Other validation approaches compatible with NEEDLE predictions include Agrobacterium rhizogenes-mediated root genetic transformation, which enables rapid functional testing in hairy root systems, and virus-mediated genome editing, which can be used to modulate candidate gene expression. When coupled with CRISPR-based validation strategies, NEEDLE significantly accelerates the functional characterization and translational application of key regulatory genes in crop improvement programs. This integrated computational-experimental framework provides a robust pipeline for confirming the biological relevance of predicted transcription factors.

Comparative Performance Analysis

Benchmarking Against Established Methods

To objectively evaluate NEEDLE's performance, developers validated its accuracy using two independent datasets before applying it to identify CSLF6 regulators. The pipeline demonstrates particular strength in its minimal computational requirements compared to other bioinformatics tools that require extensive computing resources, making it accessible to researchers without specialized computational infrastructure. Additionally, its user-friendly workflow lowers the barrier to entry for plant scientists with limited bioinformatics expertise, while maintaining robust analytical capabilities.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Gene Discovery Approaches for Non-Model Plants

| Method | Multi-omics Requirements | Computational Demand | Experimental Validation Efficiency | Accessibility for Non-Bioinformaticians |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEEDLE Pipeline | Low (uses only transcriptome data) | Minimal | High (streamlined for in planta validation) | High (user-friendly workflow) |

| Traditional Genetics | None | Low | Low (time-intensive) | High (established methods) |

| Multi-omics Integration | High (requires genomic, epigenomic, transcriptomic data) | Very High | Variable | Low (requires specialized expertise) |

| Comparative Genomics | Medium (requires cross-species genomic data) | Medium | Medium to Low | Medium |

Application-Dependent Performance Metrics

When assessed for its capability to provide biologically relevant TF predictions, NEEDLE demonstrates exceptional performance in evolutionary analysis, successfully uncovering both conserved and divergent regulatory mechanisms between Brachypodium and sorghum. This capability provides valuable insights into how regulatory networks evolve across related grass species, information that can inform translational approaches applying findings from model to crop species.

In practical applications, the pipeline has shown high predictive accuracy for identifying transcription factors regulating specific target genes associated with important traits. In the CSLF6 case study, NEEDLE successfully identified novel regulators while also mapping the network topology surrounding this key biosynthetic gene. The method's design efficiency is particularly notable, as it eliminates the need for extensive multi-omics datasets that are frequently unavailable for non-model species, while still generating high-confidence predictions suitable for guiding experimental validation.

Table 2: Experimental Data Supporting NEEDLE's Performance in TF Identification

| Performance Metric | NEEDLE Implementation | Conventional Methods (Average) | Experimental Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| TF Prediction Accuracy | Biologically relevant predictions validated in planta | Variable validation success | Confirmed regulators of CSLF6 in Brachypodium and sorghum [24] [25] |

| Data Requirements | Dynamic transcriptome data only | Multiple data types (genomic, epigenomic, etc.) | Successful with RNA-seq data alone [24] |

| Evolutionary Insight Generation | High (conservation/divergence analysis) | Limited | Revealed evolutionary patterns in grass species regulatory elements [24] |

| Technical Accessibility | User-friendly with minimal computational demands | Often requires specialized bioinformatics skills | Accessible to researchers without computational expertise [25] |

Alternative Gene Discovery and Validation Methodologies

Tissue Culture-Independent Transformation Methods

For validating gene function predictions generated by NEEDLE, several tissue culture-independent methods have emerged as valuable experimental approaches. Agrobacterium rhizogenes-mediated root genetic transformation enables researchers to study gene function in hairy root systems without the need for complex tissue culture protocols. This method is particularly valuable for species recalcitrant to regeneration from callus tissue, and has been successfully applied in species including citrus and strawberry for subcellular localization studies and preliminary functional analysis.

Another innovative approach utilizes developmental regulators (DRs) to induce transgenic shoot and root formation in planta. Research has demonstrated that these critical developmental regulators are highly conserved across different plant species, enhancing their utility for validating gene function predictions in non-model organisms. These methods offer significant advantages in reducing costs, experimental timelines, and technical barriers associated with traditional tissue culture-dependent transformation, making them particularly suitable for rapid validation of computational predictions.

Virus-Induced Gene Editing Systems

Virus-mediated genome editing represents another powerful approach for validating transcription factor function identified through computational prediction. This methodology involves infecting plants that overexpress Cas9 with viruses carrying sgRNA modules targeting candidate genes. Research has successfully employed Tobacco Rattle Virus (TRV) and Citrus Leaf Blotch Virus (CLBV) to edit endogenous genes in Cas9-overexpressing transgenic tobacco, demonstrating the efficacy of this validation approach.

These virus-based systems provide particular value for high-throughput validation of multiple candidate genes identified through NEEDLE analysis, as they can be deployed without the need for stable transformation. The methodology benefits from being both cost-effective and time-efficient, enabling researchers to quickly assess the functional relevance of predicted transcription factors before committing to more resource-intensive stable transformation experiments. When integrated with NEEDLE predictions, these validation techniques create a powerful pipeline for accelerating gene function characterization in non-model plants.

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Effective implementation of the NEEDLE pipeline requires appropriate computational tools for network visualization and analysis. Several open-source software options are available to researchers, each with particular strengths for gene regulatory network analysis. Cytoscape provides a powerful platform for visualizing complex networks and integrating these with attribute data, enabling researchers to overlay expression data or functional annotations onto network representations. Gephi offers complementary capabilities as leading visualization and exploration software for all kinds of graphs and networks, with particular strength in manipulating graphs in real-time and detecting clusters.

For researchers preferring programmatic approaches, NetworkX (a Python package) enables the creation, manipulation, and study of complex network structure, dynamics, and functions. The igraph library provides similar capabilities across multiple programming environments including R, Python, and Mathematica, offering extensive network analysis tools. These computational resources empower researchers to not only run the NEEDLE pipeline but also to explore and interpret the resulting networks through interactive visualization and custom analysis.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for NEEDLE Implementation and Validation

| Reagent/Tool | Category | Function in NEEDLE Pipeline | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA-seq Libraries | Biological Sample | Provides dynamic transcriptome data for co-expression network construction | Time-course experiments under stress conditions [24] |

| Cytoscape | Computational Tool | Visualizes and analyzes gene co-expression networks and regulatory hierarchies | Integration of network topology with gene expression data [26] |

| Agrobacterium rhizogenes K599 | Biological Reagent | Enables rapid validation of candidate genes in hairy root systems | Functional testing in citrus and strawberry [10] |

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | Molecular Tool | Validates predicted transcription factors through genome editing | Targeted mutagenesis of candidate regulatory genes [10] |

| Virus Vector Systems (TRV, CLBV) | Delivery Tool | Enables virus-mediated genome editing for high-throughput validation | Editing endogenous Pds gene in Cas9-overexpressing tobacco [10] |

Experimental Validation Reagents

For the experimental validation phase following computational prediction, several key reagents facilitate functional characterization of candidate transcription factors. Agrobacterium strains including K599 for hairy root transformation and GV3101 for standard plant transformation serve as essential delivery systems for introducing genetic constructs into plant tissues. These microbial tools enable researchers to manipulate gene expression in candidate transcription factors to assess their functional role in regulating target genes.

Molecular constructs for gene expression modulation represent another critical reagent category, including vectors for overexpression, RNA interference, and CRISPR-based genome editing. The integration of fluorescent reporters such as GFP enables researchers to visualize subcellular localization and track gene expression patterns in transformed tissues, providing important spatial context for transcription factor function. For species resistant to traditional transformation, virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) vectors offer an alternative approach for rapid functional assessment of NEEDLE-predicted transcription factors.

Integrated Workflow for Transcription Factor Discovery

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational-experimental workflow for transcription factor discovery and validation using the NEEDLE pipeline:

Diagram 1: NEEDLE Pipeline Workflow for TF Discovery and Validation

The NEEDLE pipeline represents a significant advancement in network-based discovery for transcription factor identification in non-model plant species. Its integrated computational-experimental framework effectively addresses the challenge of limited multi-omics resources while providing biologically relevant predictions validated through robust experimental approaches. When compared to conventional methods, NEEDLE demonstrates superior efficiency in its minimal data requirements, computational accessibility, and capacity for evolutionary insight generation.

The pipeline's compatibility with emerging tissue culture-independent validation methods positions it as a valuable tool for accelerating crop improvement programs. By enabling researchers to systematically identify key transcriptional regulators of important traits, NEEDLE facilitates the development of more productive and stress-resistant crops—a critical objective in addressing global food security challenges. Its application to CSLF6 regulation in grasses exemplifies how this approach can uncover both conserved and divergent regulatory elements, providing fundamental insights into the evolution of gene regulatory networks while delivering practical targets for crop enhancement.

In the field of functional genomics, a significant challenge persists in the study of non-model organisms, which include the majority of medicinal plants and specialized crop species. These organisms often possess large, complex genomes that are not fully sequenced or annotated, making conventional transcriptomic approaches difficult to apply [27]. For researchers investigating plant gene function, this genomic limitation represents a major bottleneck in linking genetic information to phenotypic traits, such as stress resistance in crops or the production of valuable secondary metabolites in medicinal plants [27]. Tag-based transcriptomic methods have emerged as powerful solutions to these challenges, with EDGE (EcoP15I-tagged Digital Gene Expression) representing a particularly effective methodology for quantifying gene expression without requiring a complete reference genome [28].

The fundamental principle underlying EDGE and similar digital gene expression techniques is the sequencing of short, unique cDNA tags that serve as molecular fingerprints for individual transcripts. By focusing on these defined regions rather than attempting full-length cDNA sequencing, EDGE achieves comprehensive transcriptome coverage with significantly reduced sequencing complexity and computational demands [28]. This approach is especially valuable for plant researchers working with species that have long life cycles, such as orchids, which may take years to reach reproductive maturity and thus present significant challenges for traditional genetic studies [6]. For these difficult-to-study species, EDGE provides a practical pathway to obtain quantitative gene expression data that can accelerate the validation of gene function and support crop improvement efforts.

EDGE Technology: Core Methodology and Workflow

Fundamental Principles of EDGE

The EDGE methodology employs ultra-high-throughput sequencing of defined 27-base pair cDNA fragments that uniquely tag corresponding genes, enabling direct quantification of transcript abundance [28]. Unlike RNA-seq, which sequences randomly fragmented transcripts of varying lengths, EDGE generates standardized, discrete sequence tags that can be precisely mapped and counted. This tag-based approach provides several distinct advantages for studying non-model plants: it eliminates transcript length bias (a known issue in RNA-seq where longer transcripts appear more abundant), exhibits minimal technical noise, and reveals an exceptionally large dynamic range of gene expression (up to 10^6) [28]. Perhaps most importantly for plant researchers, EDGE achieves transcriptome saturation after just 6-8 million reads, making it a cost-effective option for species with limited genomic resources [28].

The technology is particularly suited for detecting expression differences in poorly expressed genes, which often include transcription factors and regulatory molecules that control important agricultural traits [28]. This sensitivity to low-abundance transcripts is critical for plant gene validation studies, where key regulators may be expressed at minimal levels but exert substantial effects on phenotype. Additionally, because EDGE targets specific tag regions rather than full transcripts, it can effectively profile gene expression even when only partial gene sequences are available, as is common for non-model plant species [29].

Experimental Protocol for EDGE Analysis

The EDGE experimental workflow consists of several carefully optimized steps that ensure high-quality gene expression data:

RNA Isolation and Quality Control: Total RNA is extracted from plant tissues using standard methods, with quality verification through microfluidic analysis. For plant tissues high in secondary metabolites, additional purification steps may be required [28].

cDNA Synthesis and Tag Generation: mRNA is reverse-transcribed into cDNA using oligo(dT) primers. The cDNA is then digested with EcoP15I restriction enzyme, which generates specific 27-bp tags from defined positions within each transcript [28]. This enzyme-specific tagging creates consistent, comparable markers for each gene.

Adapter Ligation and Amplification: Specialized adapters containing sequencing motifs are ligated to the tags, followed by limited PCR amplification to create the final sequencing library. The adapter design includes barcode sequences when multiplexing multiple samples [30].

High-Throughput Sequencing: The tag library is sequenced using next-generation platforms such as Illumina, generating millions of short reads corresponding to the transcript tags [28].

Bioinformatic Analysis: Sequence tags are processed to remove low-quality reads, then mapped to available genomic or transcriptomic resources. For non-model plants with limited sequence data, de novo tag clustering can be performed, followed by annotation based on homology to related species [27].

The following diagram illustrates the complete EDGE workflow from sample preparation to data analysis:

Comparative Performance Analysis: EDGE vs. Alternative Transcriptomic Methods

Methodological Comparison with RNA-seq and Spatial Transcriptomics

When evaluating transcriptomic technologies for plant gene validation, researchers must consider multiple methodological factors that impact data quality and experimental feasibility. The table below provides a systematic comparison of EDGE against other prominent transcriptomic approaches:

Table 1: Technical Comparison of Transcriptomic Methods for Non-Model Plant Research

| Method | Optimal Use Case | Sensitivity for Low-Abundance Transcripts | Reference Genome Dependency | Typical Reads Required | Technical Noise | Transcript Length Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EDGE | Non-model organisms, gene discovery | High [28] | Low [28] | 6-8 million [28] | Very low [28] | None [28] |

| RNA-seq | Model organisms, isoform detection | Moderate [28] | High [27] | 20-30 million [27] | Moderate | Present [28] |

| Spatial Transcriptomics | Tissue localization studies | Platform-dependent (varies) [31] | Moderate to high [31] | Varies by platform | Varies by platform | Varies by platform |

| DeepSAGE | Expression profiling, sample multiplexing | High [30] | Moderate | 8-12 million [30] | Low | Minimal |

As evidenced in the table, EDGE offers distinct advantages for non-model plant research where reference genomes are often incomplete or unavailable. Its minimal technical noise and absence of transcript length bias make it particularly suitable for comparative expression studies across different treatments, developmental stages, or genetic backgrounds [28]. In contrast, spatial transcriptomics platforms like Stereo-seq, Visium HD, CosMx, and Xenium excel in situ localization of gene expression but typically require more comprehensive genomic resources and specialized instrumentation [31].

Quantitative Performance Metrics Across Platforms

Direct comparative studies provide valuable insights into the practical performance characteristics of different transcriptomic methods. The following table summarizes key quantitative metrics for EDGE and alternative approaches:

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Transcriptomic Platforms Based on Experimental Data

| Platform | Dynamic Range | Gene Detection Efficiency | Accuracy in Non-Model Systems | Cost per Sample | Experimental Simplicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EDGE | 10^6 [28] | >99% of genes [28] | High [28] | Low | Simple protocol [28] |

| RNA-seq | 10^5-10^6 | >90% (model organisms) | Moderate (requires reference) [27] | Moderate | Complex bioinformatics |

| 5'-DGE | 10^4 [32] | ~85% | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| DeepSAGE | 10^5 [30] | >95% | High [30] | Low | Simple protocol [30] |

A critical advantage of EDGE demonstrated in these comparisons is its exceptional dynamic range, which enables simultaneous quantification of both highly abundant and rare transcripts without adjustment of sequencing depth [28]. This characteristic is particularly valuable in plant gene validation studies, where key regulatory genes often express at low levels but substantially impact phenotype. For instance, when applied to cheetah skin samples (as a mammalian example), EDGE successfully identified genes controlling pigmentation differences between spotted and non-spotted regions, demonstrating its capability to detect biologically significant expression patterns in non-model systems [28].

EDGE Applications in Plant Gene Function Validation

Gene Discovery in Non-Model Plants

EDGE has proven particularly effective for functional gene mining in medicinal plants and crops where genomic information is limited. In papaya (Carica papaya), researchers utilized a related tag-based method (SuperSAGE) to identify genes involved in sex determination by analyzing flower samples from male, female, and hermaphrodite plants [29]. Through sequencing of short transcript tags, they identified 312 unique sequences specifically mapped to sex chromosome sequences, including a candidate MADS-box gene potentially responsible for female determination [29]. This application demonstrates how tag-based transcriptomics can overcome challenges posed by complex genome structures that hinder conventional approaches.

Similarly, in cucumber (Cucumis sativus), tag-sequencing analysis enabled researchers to characterize transcriptome dynamics during waterlogging stress, identifying differentially expressed genes linked to carbon metabolism, photosynthesis, reactive oxygen species handling, and hormone signaling [29]. These discoveries provide crucial insights into stress adaptation mechanisms that can inform breeding programs for more resilient crop varieties. The ability of EDGE to detect subtle expression changes in signaling pathways makes it invaluable for understanding complex regulatory networks in plants.

Integration with Functional Validation Techniques

A significant strength of EDGE in plant gene function validation is its compatibility with downstream experimental approaches. The gene expression data generated by EDGE often serves as the starting point for more targeted functional studies using techniques such as Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS). In orchids, which have long life cycles (2-3 years to flowering), researchers developed a Cymbidium mosaic virus-based VIGS system to rapidly validate gene function without waiting for the entire growth cycle [6]. This approach enabled functional assessment of floral identity genes in less than two months instead of years, demonstrating how EDGE discovery can be efficiently coupled with experimental validation [6].

Another integrative framework is the NEEDLE pipeline, which uses network analysis of dynamic transcriptome data to identify transcription factors upstream of genes of interest [7]. This approach has been successfully applied to identify regulators of cellulose synthase-like F6 (CSLF6) genes in Brachypodium and sorghum, revealing evolutionarily conserved regulatory elements among grass species [7]. The following diagram illustrates how EDGE integrates within a comprehensive gene function validation pipeline:

Essential Research Toolkit for EDGE Experiments

Successful implementation of EDGE for plant gene validation requires specific reagents and computational tools. The following table outlines key components of the EDGE research toolkit:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for EDGE Experiments

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| EcoP15I Restriction Enzyme | Generates specific 27-bp tags from cDNA | Critical for standardized tag production [28] |

| Oligo(dT) Primers | cDNA synthesis from mRNA | Selects for polyadenylated transcripts |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Library amplification | Maintains sequence accuracy during PCR |

| Illumina-Compatible Adapters | Sequencing library preparation | Includes barcodes for sample multiplexing |

| Trinity Assembly Software | De novo transcriptome assembly | Alternative when reference is unavailable [27] |

| NEEDLE Pipeline | Transcription factor identification | Identifies upstream regulators from expression data [7] |

| CymMV VIGS Vectors | Functional validation in plants | Enables rapid gene silencing in non-model species [6] |

For researchers studying non-model plants, the combination of EDGE for gene discovery with VIGS for functional validation represents a particularly powerful approach. The CymMV-based VIGS system has been successfully adapted for orchids, overcoming challenges posed by their large genome size, low transformation efficiency, and extended life cycle [6]. This methodological synergy significantly accelerates the pace of gene characterization in difficult-to-study species.

EDGE represents a robust, sensitive, and cost-effective solution for digital gene expression profiling in non-model plants, addressing critical challenges in functional genomics for species with limited genomic resources. Its advantages in detecting expression differences for poorly expressed genes, minimal technical noise, and absence of transcript length bias make it particularly suitable for plant gene validation studies [28]. When integrated with complementary approaches such as VIGS for functional assessment and network analysis tools like NEEDLE for regulator identification, EDGE provides a comprehensive framework for elucidating gene function in diverse plant species [7] [6].