Breaking the Barrier: Advanced Solutions for Transforming Recalcitrant Plant Species

Genetic transformation is a cornerstone of modern plant research and crop improvement, yet many plant species remain notoriously recalcitrant to established protocols.

Breaking the Barrier: Advanced Solutions for Transforming Recalcitrant Plant Species

Abstract

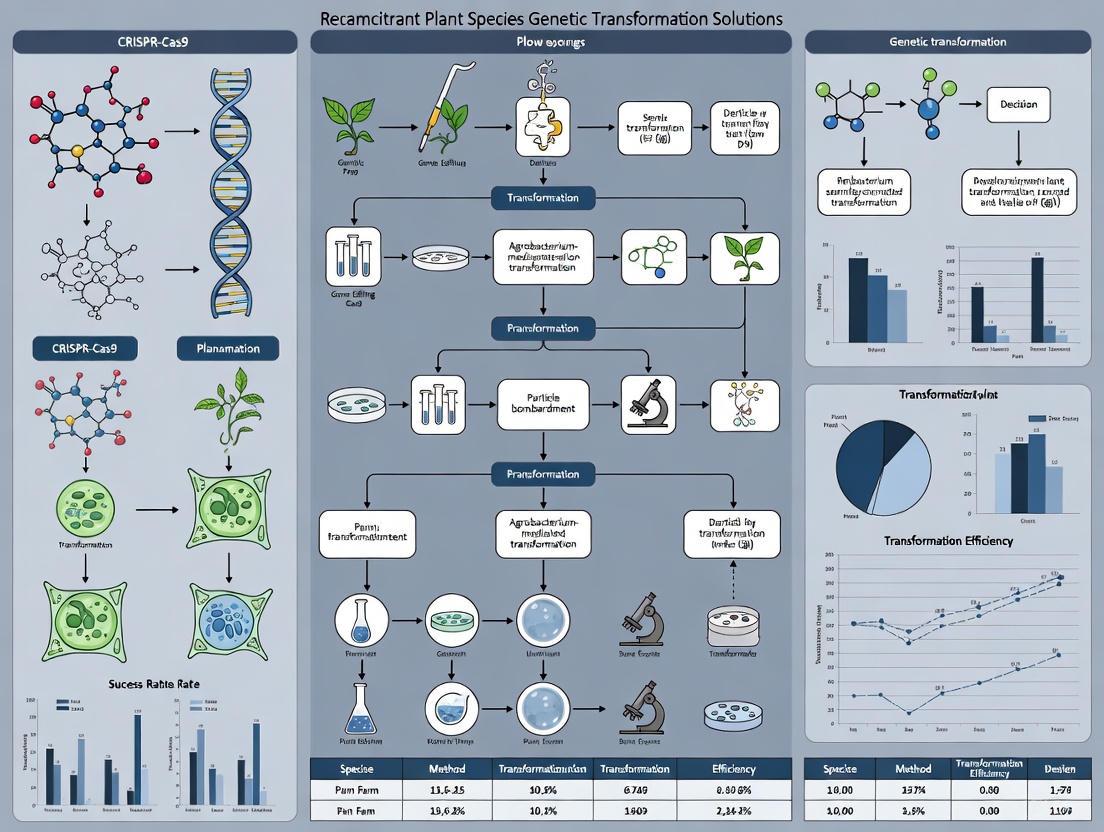

Genetic transformation is a cornerstone of modern plant research and crop improvement, yet many plant species remain notoriously recalcitrant to established protocols. This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the latest scientific breakthroughs designed to overcome this bottleneck. We explore the foundational biological causes of recalcitrance, from potent immune responses to limited regenerative capacity. The review delves into cutting-edge methodological solutions, including morphogenic gene overexpression and novel in planta delivery systems, which bypass traditional tissue culture. Furthermore, we offer a practical guide for troubleshooting and optimizing transformation protocols, and conclude with a comparative evaluation of these emerging strategies. This resource is tailored for researchers, scientists, and biotechnology professionals seeking to apply genetic engineering and genome editing to a wider array of plant species for both agricultural and biomedical advancements.

Understanding Recalcitrance: The Biological Barriers to Plant Transformation

Plant recalcitrance refers to the inherent resistance of many plant species and genotypes to genetic transformation and in vitro regeneration. This resistance presents a major bottleneck for crop improvement, functional genomics, and the development of new plant varieties, affecting a wide range of species from legumes and forest trees to medicinal plants [1] [2] [3].

The challenges are not merely technical; they are rooted in the plant's fundamental biology. Key factors contributing to recalcitrance include:

- Plant Immune Response: Agrobacterium tumefaciens, a common vector for plant transformation, is recognized by the plant as a pathogen. This triggers a strong immune response, involving the expression of defense-related genes and pathogen-induced programmed cell death, which can eliminate transformed cells before they can regenerate [4].

- Transcriptional and Regenerative Rigidity: Some plant cells, particularly in certain genotypes, exhibit a strong resistance to the cellular reprogramming required for dedifferentiation (callus formation) and subsequent redifferentiation (organogenesis). This rigidity is governed by complex gene regulatory networks [4] [3].

- Genotype Dependence: Even within a readily transformable species, elite commercial varieties are often notoriously recalcitrant. In wheat, for example, the model genotype Fielder can achieve over 45% transformation efficiency, while commercial varieties like Jimai22 achieve only 2.7-5.8%, and others like Aikang58 fail entirely [5]. Similar disparities exist in soybean and other crops [5].

Table 1: Transformation Efficiencies Across Selected Plant Species

| Plant Name | Transformation Efficiency (%) | Classification | Key Explant(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lotus japonicus | 94 [1] | Susceptible | Seeds |

| Alfalfa | 90 [1] | Susceptible | Leaflets |

| Nicotiana tabacum | 100 [1] | Susceptible | Leaf |

| Soybean (certain models) | 34.6 [1] | Susceptible | Seeds |

| Vigna radiata (Mung Bean) | 1.49 - 4.2 [1] | Recalcitrant | Shoot tip, Cotyledonary node |

| Vigna unguiculata (Cowpea) | 3.09 [1] | Recalcitrant | Cotyledonary node |

| Wheat (Recalcitrant variety) | 2.7 - 5.8 [5] | Recalcitrant | Immature embryo |

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs for Researchers

This section addresses common experimental problems and provides evidence-based solutions.

FAQ: What are the primary biological barriers causing low transformation efficiency?

The main barriers are multi-layered. First, the plant immune system perceives the transformation process (e.g., Agrobacterium infection, tissue wounding) as an attack, launching a defense response that kills transformed cells [4]. Second, many cells, especially in elite cultivars, lack the cellular plasticity to be reprogrammed. Their transcriptional networks are "locked," preventing the dedifferentiation and regeneration necessary to produce a whole plant from a single transformed cell [4] [3]. Finally, the toxic stress of selection agents, such as antibiotics, adds another layer of pressure that recalcitrant cells cannot survive [4].

FAQ: Our team works with a recalcitrant legume. Are there alternatives to standard tissue culture?

Yes, in planta transformation strategies are gaining traction as they bypass or minimize tissue culture. These methods transform intact plants or tissues without relying on callus culture and regeneration [6]. They are often considered more genotype-independent. Common techniques include the floral dip method (used famously for Arabidopsis), pollen-tube pathway-mediated transformation, and shoot apical meristem (SAM) injury methods where Agrobacterium is applied to wounded meristems [6]. These approaches are technically simpler, more affordable, and can be easier to implement in labs focused on minor crops.

FAQ: We achieve good callus formation, but regeneration fails. What could be the cause?

This is a classic symptom of recalcitrance, often linked to an inability to transition from the dedifferentiation phase to the organogenic phase. The problem frequently lies in the balance and sensitivity of plant growth regulators [4] [2]. Suboptimal concentrations of auxins and cytokinins, or the plant's inability to respond to them, can block shoot initiation. Furthermore, the accumulation of toxic compounds like reactive oxygen species (ROS) or phenolic compounds in the culture medium from wounded tissues can inhibit regeneration [3]. Finally, the transformation and selection stress itself can weaken cells, causing them to lose their regenerative potential, meaning only non-transformed cells regenerate [4].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Leveraging Developmental Regulator Genes to Enhance Transformation

Principle: Ectopic expression of key developmental regulatory (DEV) genes can reprogram somatic cells, enhance pluripotency, and boost regeneration capacity, thereby overcoming genotype-dependent recalcitrance [3] [5].

Methodology:

Gene Selection: Choose one or more morphogenic genes. Highly effective candidates include:

- TaWOX5: A WUSCHEL-related homeobox transcription factor shown to dramatically improve transformation in recalcitrant wheat, from 5.8% to 55.4% in Jimai22 [5].

- BBM/WUS2 Combination: The genes ZmBBM (Baby Boom) and ZmWUS2 (Wuschel2) from maize, when co-expressed, strongly promote somatic embryogenesis. This system has been adapted for use in monocots like rice, sorghum, and wheat [5].

- GRF-GIF Chimeras: Fusion proteins of Growth-Regulating Factors (GRFs) and their co-activators GIFs can significantly accelerate shoot regeneration in recalcitrant species like cassava, soybean, and sunflower [2] [5].

Vector Construction: Clone the selected DEV gene(s) under a constitutive or tissue-specific promoter into your transformation vector.

Transformation & Excision:

- Co-transformation: Co-deliver the DEV gene vector alongside your gene-of-interest vector into plant explants using Agrobacterium or biolistics.

- "Altruistic" Transformation: Use a mixed Agrobacterium culture (e.g., 9:1 ratio of gene-of-interest strain to DEV gene strain). The DEV gene is transiently expressed in neighboring cells, stimulating embryogenesis that non-autonomously aids the regeneration of cells transformed with your gene of interest [5].

- Marker Excision: To avoid pleiotropic effects in mature plants, design the system to allow for the excision of the morphogenic genes after regeneration using site-specific recombinase systems (e.g., Cre-lox) [5].

Protocol 2: Implementing an In Planta Transformation Strategy

Principle: To bypass tissue culture recalcitrance by transforming cells within the intact plant that are naturally destined to become the next generation (e.g., gametes, zygotes, or meristems) [6].

Methodology (Floral Dip/Drench Example):

- Plant Growth: Grow healthy plants until the stage of early bolting and flower bud development.

- Agrobacterium Preparation:

- Inoculate a single colony of Agrobacterium tumefaciens harboring your binary vector into liquid medium with appropriate antibiotics.

- Grow the culture overnight at 28°C until it reaches an OD₆₀₀ of ~0.8.

- Centrifuge and resuspend the bacterial pellet in a transformation medium (e.g., 5% sucrose solution, often supplemented with a surfactant like Silwet L-77 at 0.01-0.05%).

- Plant Transformation:

- For Floral Dip, carefully invert the above-ground parts of the plant (with developing inflorescences) into the Agrobacterium suspension for 5-15 seconds with gentle agitation.

- For Floral Drench, apply the bacterial suspension directly to the shoot apical meristem and flower buds using a pipette or spray bottle.

- Post-Transformation Care:

- Lay the treated plants on their sides and cover with transparent plastic wrap or a dome to maintain high humidity for 16-24 hours.

- Return plants to normal growth conditions and allow seeds to develop.

- Selection: Harvest seeds (T1 generation) and sow them on soil or selective media to identify positive transformants.

Key Signaling Pathways & Molecular Mechanisms

The following diagram summarizes the core regulatory pathways that influence plant cell recalcitrance and the points of intervention using developmental factors.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Overcoming Recalcitrance

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Mechanism | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Morphogenic Genes (BBM, WUS/WOX) | Master regulators that induce somatic embryogenesis and stem cell proliferation, forcing regeneration in recalcitrant tissues. | Maize, Sorghum, Wheat transformation [5]. |

| GRF-GIF Chimeric Proteins | Transcription factor complexes that dramatically enhance shoot regeneration efficiency without developmental abnormalities. | Cassava, Soybean, Brassica napus [2] [5]. |

| Novel Agrobacterium Strains | Engineered strains (e.g., with Type III Secretion Systems) that better suppress plant immune responses during infection. | Enhanced delivery of T-DNA into plant cells [7]. |

| Plant Growth Regulators (Meta-topolin) | Synthetic cytokinins that can be more effective than traditional ones like BAP in inducing shoot formation in recalcitrant species. | Improved morphogenesis in medicinal plants like Pterocarpus marsupium [2]. |

| Nanoparticles | Used as carriers for delivering genetic material (DNA, CRISPR/Cas9 RNP) or hormones, bypassing pathogen-triggered responses. | Shoot regeneration in water hyssop; potential for universal delivery [2]. |

| Trichostatin A | A histone deacetylase inhibitor that alters the epigenetic state of cells, potentially unlocking regenerative potential. | Shown to increase regeneration in Arabidopsis and other species [4]. |

| In Planta Vectors | Binary vectors optimized for methods like floral dip, often containing specific selectable markers and T-DNA architectures. | Transformation of Arabidopsis, rice, and chickpea without tissue culture [6]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why do some plant species or varieties resist genetic transformation more than others? Recalcitrance to Agrobacterium-mediated transformation is often linked to the intensity and timing of the plant's innate immune response. Species that readily accept foreign DNA typically mount a weaker or more suppressed defense, while recalcitrant plants activate a strong defense repertoire involving Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases (MAPKs), defense gene expression, production of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS), and hormonal adjustments. The plant's immune system recognizes Agrobacterium as a pathogen, creating a barrier to transformation [8] [4].

FAQ 2: What specific plant immune responses are triggered by Agrobacterium infection? The plant immune system responds to Agrobacterium on multiple fronts:

- PAMP-Triggered Immunity (PTI): The plant recognizes conserved microbial molecules from Agrobacterium, such as Elongation Factor Thermo Unstable (EF-Tu), through cell-surface Pattern Recognition Receptors (PRRs) like EFR. This recognition triggers a broad defense response [8] [9].

- Effector-Triggered Immunity (ETI): If the bacterium succeeds in suppressing PTI, intracellular NLR immune receptors can recognize specific bacterial effectors, leading to a stronger, often localized Hypersensitive Response (HR) involving programmed cell death [9].

- Transcriptional Reprogramming: Infection leads to large-scale changes in the expression of host genes, particularly those related to defense. Successful transformation is often associated with the suppression of these defense-related genes at later stages of infection [8].

FAQ 3: Are there documented trade-offs between transformability and disease resistance in plants? Yes. Evidence shows that plant cultivars known for high transformability often exhibit reduced resistance to pathogens. For example, the highly transformable wheat cultivar 'Fielder' is particularly susceptible to diseases like Fusarium head blight, stripe rust, and powdery mildew. Similarly, the 'Bobwhite' wheat cultivar is vulnerable to Fusarium graminearum and Hessian fly. This suggests that the genetic traits which make a plant amenable to transformation might concurrently weaken its general immune defenses [4].

FAQ 4: What are some experimental strategies to suppress plant immunity and improve transformation? Researchers have developed several innovative strategies to overcome the plant immune barrier:

- Engineering Agrobacterium with a Type III Secretion System (T3SS): This involves modifying Agrobacterium to deliver bacterial effectors from Pseudomonas syringae (e.g., AvrPto, AvrPtoB, HopAO1) that naturally suppress host defenses. This method has been shown to increase transformation efficiency in wheat, alfalfa, and switchgrass by 250% to 400% [10].

- Virus-Mediated Silencing of Immunity Genes: Transient silencing of key defense genes, such as those involved in salicylic acid biosynthesis or ethylene signaling, in host plants like Nicotiana benthamiana has been shown to increase subsequent transgene expression [4].

- Using Plant Hormones and Supplements: The addition of compounds like melatonin to nitrogen-depleted culture media has been shown to strongly enhance Agrobacterium-mediated transformation in carnation [4].

FAQ 5: How can I choose a better plant genotype or cultivar for transformation? Selection of the right plant material is critical. If available, opt for cultivars or accessions with known higher transformation efficiency. As a general rule, many of these transformable genotypes show reduced resistance to common pathogens, which can be a useful initial screening indicator [4]. The table below compares the transformation efficiency and disease susceptibility of different wheat cultivars.

| Plant/Cultivar | Transformation Efficiency | Disease Susceptibility | Key Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat 'Fielder' | High | Susceptible to Fusarium head blight, stripe rust, powdery mildew [4] | A model transformable genotype [4]. |

| Wheat 'Bobwhite' | High | Vulnerable to F. graminearum, Hessian fly [4] | Another transformable wheat cultivar [4]. |

| Legumes (e.g., peanut, chickpea) | Generally Low (Recalcitrant) | Not specified in context | Recalcitrance is a major hindrance to genome editing [11]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Transient Transformation Efficiency

Potential Cause: A strong, early PAMP-Triggered Immunity (PTI) response is preventing T-DNA transfer or early expression.

Solutions:

- Use engineered Agrobacterium: Employ Agrobacterium strains engineered with a T3SS to deliver defense-suppressing effectors like AvrPto during co-cultivation [10].

- Optimize the co-cultivation environment: Maintain a stable, non-alkaline pH in the culture medium, as a stable pH has been shown to suppress defense signaling and enhance transient expression in Arabidopsis seedlings [4].

- Select susceptible genotypes: Utilize plant varieties known for their high transformability, such as the Ageratum conyzoides cell culture, which demonstrates higher competence compared to standard tobacco BY-2 cells or Arabidopsis tissues [12].

Problem: Failure to Generate Stable Transgenic or Genome-Edited Plants

Potential Cause: Plant defense responses are causing cell death or inhibiting the regeneration of transformed cells. The selection process may also be adding excessive stress.

Solutions:

- Weaken the immune system transiently: Implement virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) to temporarily knock down key immunity regulators like NPR1 or EIN2 in the explants before transformation [4].

- Improve regeneration protocols: Optimize the balance of auxins and cytokinins in the culture media. Consider using morphogenic genes like GRF-GIF chimeras to boost regeneration capacity, a method that has shown success in recalcitrant species [4] [2].

- Modulate selection pressure: Carefully titrate the concentration of antibiotics used for selection. High concentrations can add excessive stress, causing the loss of regenerative potential in transformed cells. Using alternative selection markers can also help [4].

Problem: Low Transformation Efficiency in Legume Crops

Potential Cause: Legumes are notoriously recalcitrant to transformation, which directly hampers genome editing efforts, as transformation is a prerequisite for delivering editing reagents [11].

Solutions:

- Exploit genotype-dependent efficiency: Be aware that transformation efficiency varies dramatically between legume species and even cultivars. For example, efficiency in soybean can be over 16%, while in pigeon pea it can be as low as 0.2% [11].

- Use alternative explants: Research and identify the most responsive explants for your specific legume species. Embryonic or meristematic tissues often have higher regenerative potential [2] [11].

- Apply novel regeneration-enabling methods: Deliver morphogenic genes like GRF/GIF chimeras via nanoparticles or Agrobacterium to kickstart the regeneration process in recalcitrant species [2].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Enhancing Transformation using T3SS-EngineeredAgrobacterium

This protocol details the use of Agrobacterium engineered with a Pseudomonas syringae Type III Secretion System (T3SS) to deliver defense-suppressing effector proteins, thereby increasing transformation efficiency [10].

Key Reagents:

- pLN18 plasmid (contains the Pss61 T3SS gene cluster) [10].

- Plasmid for expressing a T3 effector (e.g., AvrPto, AvrPtoB, HopAO1) under its native promoter.

- Disarmed Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain (e.g., EHA105).

- Appropriate binary vector with a reporter gene (e.g., GUS-intron).

Methodology:

- Strain Engineering: Introduce the pLN18 plasmid and the effector-expressing plasmid into the disarmed Agrobacterium strain containing your binary vector of interest. Use standard molecular biology techniques like conjugation or electroporation.

- Plant Inoculation: Inoculate your plant material (e.g., leaf discs, cell cultures) with the engineered Agrobacterium strain. For stable transformation, use a tumorigenic strain like A208 in a root transformation assay.

- Co-cultivation: Co-cultivate the bacteria and plant material for 2-3 days.

- Analysis: Assess transformation efficiency by counting tumors, measuring reporter gene activity (e.g., GUS staining), or using a split-GFP system to confirm protein delivery into plant cells [10].

The following workflow visualizes the key steps in this experimental approach:

Protocol 2: Assessing Defense Gene Expression During Infection

This method uses quantitative PCR (qPCR) to monitor the expression of defense-related genes, helping to diagnose the strength of the plant immune response during transformation experiments [8] [12].

Key Reagents:

- Plant material inoculated with Agrobacterium and mock-inoculated controls.

- RNA extraction kit.

- cDNA synthesis kit.

- qPCR reagents and primers for defense genes (e.g., PR1, PAL).

Methodology:

- Sample Collection: Collect plant tissue at multiple time points post-inoculation (e.g., 0, 6, 12, 24, 48 hours).

- RNA Extraction & cDNA Synthesis: Extract total RNA from all samples and synthesize cDNA.

- qPCR Analysis: Perform qPCR using primers for your target defense genes and housekeeping genes for normalization.

- Data Interpretation: Compare the gene expression profiles between Agrobacterium-inoculated and mock-inoculated samples. A successful transformation is often associated with an initial peak of defense gene expression followed by suppression at later time points [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential reagents and materials used in modern plant transformation research to overcome immune-related recalcitrance.

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| T3SS-Engineered Agrobacterium | Agrobacterium strain modified with a Type III Secretion System from P. syringae to deliver protein effectors that suppress plant immunity [10]. | Increasing stable transformation in recalcitrant crops like wheat and switchgrass by co-delivering effectors like AvrPto [10]. |

| Defense-Suppressing Effectors (AvrPto, AvrPtoB) | Bacterial proteins injected into plant cells to inhibit PRR signaling complexes, thereby suppressing PTI [9] [10]. | Delivered via engineered T3SS to enhance transient and stable transformation efficiency in multiple plant species [10]. |

| Morphogenic Regulators (GRF-GIF Chimeras) | Fusions of GROWTH-REGULATING FACTOR (GRF) and GRF-INTERACTING FACTOR (GIF) proteins that boost plant regeneration capacity [4] [2]. | Overcoming regeneration recalcitrance in medicinal plants and crops, improving the recovery of transformed shoots [2]. |

| Pattern Recognition Receptors (PRRs) | Plant cell-surface receptors (e.g., EFR, FLS2) that recognize PAMPs to initiate PTI. Can be transferred across species to confer new resistance [9]. | Engineering broad-spectrum disease resistance by transferring Arabidopsis EFR into tomato, potato, and citrus [9]. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | A genome editing tool that allows for precise knockout of host susceptibility (S) genes or negative regulators of immunity [9] [11]. | Creating knock-out mutants of S genes to enhance innate disease resistance without compromising other traits [9]. |

Signaling Pathways in Agrobacterium-Plant Interaction

The diagram below illustrates the core components of the plant immune system that are activated in response to Agrobacterium infection and the bacterial counter-strategies used to enable transformation.

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This technical support center is designed for researchers facing the regeneration bottleneck—the critical failure point where genetically transformed cells or tissues fail to develop into complete plants. Within the broader context of solving genetic transformation in recalcitrant species, this resource provides targeted, practical solutions to specific experimental hurdles in somatic embryogenesis and organogenesis. The protocols and insights herein are particularly vital for genome editing applications in legumes, medicinal plants, and other recalcitrant species where transformation success is a major limiting factor [4] [2] [11].

Troubleshooting Common Regeneration Problems

FAQ 1: My explants are turning brown and dying soon after culture initiation. What can I do to prevent this?

Answer: Browning or tissue necrosis is a common stress response, often due to the production and oxidation of phenolic compounds [13].

- Solution 1: Incorporate Antioxidants. Add antioxidants such as ascorbic acid or citric acid to the culture media. These compounds reduce phenolic oxidation, preventing the accumulation of toxic compounds [13].

- Solution 2: Adjust Culture Conditions. Keep the initial cultures in low-light or dark conditions to reduce oxidative stress. Additionally, perform frequent subculturing (transfer to fresh media) to remove the phenolic compounds that have leached into the medium [13].

- Solution 3: Use Adsorbents. Supplement the medium with activated charcoal (0.1-0.3%). It acts as an adsorbent, binding to phenolic compounds and other inhibitors, thus reducing tissue browning [14].

FAQ 2: My cultures are not forming embryos or shoots, or the response is very low. How can I improve regeneration efficiency?

Answer: A poor explant response can stem from several factors, including the explant source, growth regulators, and genotype.

- Solution 1: Optimize Explant Selection. The type and physiological age of the explant are critical. Young, juvenile explants (e.g., embryonic, meristematic, or seedling tissues) generally have a much higher regenerative capacity than older, differentiated tissues from mature plants [14] [2].

- Solution 2: Re-balance Plant Growth Regulators (PGRs). The balance between auxins and cytokinins is paramount [14].

- For shoot organogenesis, a medium with a higher ratio of cytokinins to auxins is typically required.

- For somatic embryogenesis, a common strategy is to initiate callus on a high-auxin medium (e.g., 2,4-D), then transfer to a low-auxin or auxin-free medium to stimulate embryo development [14].

- Consider using potent cytokinins like Thidiazuron (TDZ), which has been shown to be highly effective for shoot regeneration in many recalcitrant species [14].

- Solution 3: Address Genotypic Recalcitrance. Some species and genotypes are inherently more difficult to regenerate. Strategies include [2]:

- Screening multiple cultivars to identify one with higher regeneration potential.

- Using morphogenic genes such as GRF-GIF chimeras or other regeneration-transcription factors to boost regenerative capacity.

- Modulating the immune response, as transformation recalcitrance is often linked to a strong defense response to wounding and Agrobacterium infection [4].

FAQ 3: My regenerated shoots are vitrified (water-soaked, translucent, and brittle). How can I restore normal growth?

Answer: This physiological disorder, known as hyperhydricity (or vitrification), is often caused by poor culture conditions.

- Solution 1: Modify the Physical Medium. Increase the concentration of the gelling agent (e.g., agar) to provide a firmer support structure and reduce water availability to the tissues [13].

- Solution 2: Control the Gaseous Environment. Improve ventilation of the culture vessels to lower humidity and allow for gas exchange. This can be achieved by using vented lids or gas-permeable sealing tapes [15]. This also helps dissipate ethylene, which can accumulate in closed vessels and inhibit normal morphogenesis [15].

- Solution 3: Adjust Medium Osmolarity. Add non-toxic osmotic agents like mannitol or sorbitol to the media. This reduces water uptake by the plant tissues, alleviating the water-soaked appearance [13].

FAQ 4: I have successfully obtained transgenic callus, but it fails to regenerate into plants. What could be the issue?

Answer: This is a classic manifestation of the regeneration bottleneck, often linked to the stress of the transformation process itself.

- Solution 1: Mitigate Transformation Stress. The processes of Agrobacterium infection and antibiotic selection impose significant stress, which can suppress the regenerative potential of cells. Using weakly virulent Agrobacterium strains or adding melatonin to the co-cultivation media have been shown to improve transformation and regeneration efficiency in some species by reducing the immune response [4].

- Solution 2: Optimize the Selection and Regeneration Protocol. Ensure that the selection agent (e.g., antibiotic) concentration is not too high, as it can be overly stressful. A "honeycomb" model of regeneration suggests that only the most robust, non-transformed cells on the periphery of a callus may regenerate under strong selection pressure, while the stressed, transformed cells in the center fail to do so [4].

- Solution 3: Exploit Hormonal Crosstalk. Recent research highlights the role of ethylene in modulating regeneration. Ethylene production is a known stress response and can either promote or inhibit regeneration depending on the species. Using ethylene inhibitors (e.g., silver nitrate, AVG) or precursors (e.g., ACC) can be tested to see if it reverts recalcitrance in your specific system [15].

Quantitative Data for Experimental Design

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Plant Regeneration Pathways

| Characteristic | Organogenesis | Somatic Embryogenesis |

|---|---|---|

| Process | Formation of individual organs (shoots or roots) from explants [14] | Formation of bipolar embryo structures (with root and shoot axes) from somatic cells [14] |

| Advantages | - Lower chance of mutation in direct organogenesis [14]- Ideal for clonal propagation with high genetic fidelity [14] | - Large-scale production via embryogenic cell lines [14]- Single-cell origin reduces chimerism [14]- Enables long-term storage via synthetic seeds [14] |

| Disadvantages | - High somaclonal variation in indirect organogenesis [14]- Not standardized for many recalcitrant species [14] | - Often asynchronous development [14]- Regeneration potential can decrease over time [14] |

| Typical PGRs | Balanced ratio of Cytokinins (e.g., TDZ, BAP) and Auxins (e.g., NAA, IAA) [14] | High Auxin (e.g., 2,4-D) for induction, followed by reduced auxin for embryo development [14] |

Table 2: Critical Factors Influencing Regeneration Success

| Factor | Impact on Regeneration | Experimental Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Explant Type | Determines regenerative competence [14] | Use young, meristematic tissues (e.g., embryonic axes, shoot tips, leaf basal meristems). Test different explants from the same mother plant [14] [2]. |

| Plant Growth Regulators | Directs cell fate (callus, shoot, root, embryo) [14] | Systematically test auxin:cytokinin ratios. Use potent compounds like TDZ. Evaluate synthetic cytokinins like meta-Topolin [14] [2]. |

| Genotype | Some species/cultivars are highly recalcitrant [11] | Screen multiple genotypes. Use GRF-GIF chimera genes to boost regeneration [2]. |

| Culture Environment | Light, temperature, and vessel atmosphere affect morphogenesis [14] [15] | Test light vs. dark conditions for specific stages. Use vented lids to manage ethylene accumulation [14] [15]. |

Visualizing the Regeneration Bottleneck in Recalcitrant Species

The following diagram illustrates the key failure points in the transformation and regeneration pipeline for recalcitrant plants and identifies potential intervention strategies.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Overcoming Regeneration Recalcitrance

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Thidiazuron (TDZ) | A potent synthetic cytokinin that promotes shoot organogenesis [14] | Particularly effective in recalcitrant species. Can be used alone or in combination with auxins [14] [2]. |

| GRF-GIF Chimera Genes | Fusion proteins that act as potent master regulators of plant regeneration [2] | Transient expression of these genes can dramatically boost the regenerative capacity of transformed cells, overcoming genotypic limitations [2]. |

| Silver Nitrate (AgNO₃) | An ethylene action inhibitor [15] | Adding to culture media can counteract the inhibitory effects of ethylene accumulation in sealed vessels, potentially improving shoot regeneration [15]. |

| Activated Charcoal | Adsorbent for phenolic compounds and toxins [14] | Used to reduce tissue browning and remove inhibitory substances from the medium. Also mitigates light-induced oxidative reactions [14]. |

| Morphogenic Regulators | Compounds that enhance embryogenic competence [14] | Amino acids (e.g., glutamine, proline) and brassinosteroids (e.g., 24-epibrassinolid) have been reported to enhance somatic embryogenesis in some species [14]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs for Plant Genetic Transformation

FAQ 1: Why is my transformation efficiency so low, and how can I improve it?

Low transformation efficiency is often due to genotype recalcitrance, suboptimal culture medium, or inappropriate explant selection [16] [17].

- Solution for Genotype Recalcitrance: Consider using developmental regulator genes (DEV genes) to enhance cellular reprogramming and regeneration. Key candidates include:

- BBM/WUS2: Co-expression promotes somatic embryogenesis and has been successfully used to transform recalcitrant maize, sorghum, and wheat genotypes [16].

- GRF-GIF: A chimeric transcription factor complex that promotes shoot regeneration. It has improved transformation in tomato, wheat, rice, and lettuce [16] [18].

- WOX Genes: Such as TaWOX5 in wheat, which dramatically improved transformation efficiency and reduced genotype dependency [16].

- Solution for Medium Optimization: Ensure your culture medium supports all regeneration stages. The table below summarizes critical components [19] [20].

Table 1: Key Components for Plant Regeneration Media

| Component Type | Commonly Used Options | Function & Optimization Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Basal Medium | Murashige and Skoog (MS) salts [19] [21] | Provides essential macro and micronutrients. May require additives like proline or extra copper for some species [19]. |

| Carbon Source | Sucrose (2-3%) or Maltose (3%) [19] | Supplies energy. Maltose can be superior for some cereals like oats and lilies [19]. |

| Auxins (Callus Induction) | 2,4-D, Picloram, NAA [19] | Promotes dedifferentiation and callus formation. Concentration is critical; e.g., 2.5 mg/L 2,4-D was optimal for broomcorn millet [20]. |

| Cytokinins (Shoot Regeneration) | BAP, TDZ, Zeatin [19] | Stimulates shoot organogenesis. For example, 2 mg/L BAP was effective for broomcorn millet shoot regeneration [20]. |

| Other Additives | Silver nitrate, Glutamine, Activated Charcoal [19] | Can improve regeneration in recalcitrant species by reducing oxidative browning or adsorbing inhibitory compounds [19]. |

FAQ 2: My explants produce callus but fail to regenerate shoots. What should I do?

This indicates a blockage in the redifferentiation process, often linked to an imbalance in plant growth regulators (PGRs) [19].

- Solution: Transfer callus to a shoot regeneration medium (SRM) with a lower auxin-to-cytokinin ratio [19]. The hormone shift is critical for triggering shoot formation. Also, ensure that antibiotics used to suppress Agrobacterium are not inhibiting plant cell growth, as they can delay or prevent regeneration [19].

FAQ 3: How can I overcome the challenge of genotype dependence in transformation?

Genotype dependence is a major bottleneck, especially in crops and woody trees [16] [3].

- Solution 1: Exploit Natural Regeneration Capacity: Systematically test different explant sources. Research in poplar showed that roots, in addition to leaves and stems, can be highly efficient explants for transformation [21].

- Solution 2: Adopt In Planta Transformation: Methods like the "pollen-tube pathway" or "leaf-cutting transformation (LCT)" can bypass complex tissue culture and are often less genotype-dependent [17] [22] [23]. These techniques are simpler and do not always require sterile tissue culture.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Agrobacterium-mediated Transformation of Broomcorn Millet

This protocol, adapted from [20], provides a step-by-step guide for transforming a recalcitrant crop.

1. Explant Preparation and Callus Induction

- Material: Dehusked mature seeds of broomcorn millet 'Longmi 4'.

- Sterilization: Treat seeds with 75% ethanol (1 min) followed by 20% sodium hypochlorite (5 min), then rinse thoroughly with sterile water [20].

- Callus Induction Medium (CIM): MS salts, vitamins, 300 mg/L casein enzymatic hydrolysate, 600 mg/L L-proline, 30 g/L maltose, 3 g/L Phytagel, 2.5 mg/L 2,4-D, and 0.5 mg/L BAP [20].

- Culture: Incubate seeds on CIM in the dark at 26 ± 2°C for 2-4 weeks to generate embryogenic callus [20].

2. Agrobacterium Infection and Co-cultivation

- Vector: A binary vector (e.g., pRHVcGFP) with a GFP reporter and hpt (hygromycin resistance) selectable marker [20].

- Agrobacterium Strain: EHA105.

- Preparation: Grow Agrobacterium in LB with antibiotics to OD₆₀₀ = 1.0. Pellet and resuspend in inflation medium (MS salts, 30 g/L maltose, 2.5 mg/L 2,4-D, 0.5 mg/L BAP, 0.3 g/L casein hydrolysate, pH 5.2) supplemented with 200 µM acetosyringone. Adjust final OD₆₀₀ to 0.5 [20].

- Infection and Co-culture: Immerse embryogenic calli in the Agrobacterium suspension for 30 minutes. Blot dry and co-cultivate on solid CCM (similar to CIM with 200 µM acetosyringone) in the dark at 22°C for 3 days [20].

3. Selection and Regeneration

- Selection: After co-culture, wash calli and transfer to selection medium (CIM supplemented with 20 mg/L hygromycin and 300 mg/L Timentin). Culture in the dark for 3-4 weeks [20].

- Shoot Regeneration: Transfer resistant calli to Shoot Regeneration Medium (SRM): MS salts with vitamins, 2 mg/L BAP, 0.5 mg/L NAA, 15 g/L maltose, 300 mg/L casein hydrolysate, 3 g/L Phytagel, with hygromycin and Timentin. Culture under a 16/8 h light/dark cycle at 26°C [20].

- Rooting: Regenerated shoots (~1-2 cm) are transferred to half-strength MS medium with 30 g/L sucrose for root development [20].

Broomcorn Millet Transformation Workflow

Protocol: Testing Explant Efficiency in Woody Species

This protocol is based on a study in Poplar, which systematically compared explants [21].

1. Plant Material and Explant Collection

- Source: Collect leaf, stem (internode), petiole, and root explants from 6-8 week-old in vitro Populus plants (e.g., clone 717-1B4) [21].

2. Transformation and Regeneration

- Transformation: Follow established Agrobacterium tumefaciens (e.g., strain GV3101)-mediated transformation protocols for your species.

- Regeneration Media Sequence:

- Callus Induction Medium: MS-based, supplemented with 10 µM NAA (auxin) and 5 µM 2ip (cytokinin). Culture in dark for 3 weeks [21].

- Shoot Induction Medium: MS-based, supplemented with 0.2 µM TDZ (cytokinin). Culture for 8 weeks [21].

- Shoot Elongation Medium: MS-based, supplemented with 0.1 µM BAP (cytokinin). Culture for 4 weeks [21].

- Rooting Medium: MS-based, supplemented with 0.5 µM IBA (auxin) [21].

- Include appropriate selection agents (e.g., kanamycin) and antibiotics to eliminate Agrobacterium (e.g., timentin) throughout the process.

3. Data Collection and Analysis

- Track Efficiency: For each explant type, calculate:

- Regeneration Efficiency (%) = (Number of explants producing shoots / Total number of explants) × 100.

- Transformation Efficiency (%) = (Number of independent transgenic events / Total number of explants inoculated) × 100 [21].

Table 2: Example of Explant Performance in Poplar Transformation

| Explant Source | Key Findings from Poplar Study |

|---|---|

| Root | Demonstrated considerable regeneration capacity and transformation amenability. Resulting transformants had comparable morphology and gene expression to those from aerial explants [21]. |

| Leaf | Commonly used in aspens with high success rates. Serves as a standard for comparison [21]. |

| Stem & Petiole | Performance varies by species. In cottonwoods, these explants often perform better than leaves [21]. |

Signaling Pathways in Plant Regeneration

The process of regeneration during transformation is governed by complex signaling pathways. Key regulators and their interactions are outlined below.

Key Regulatory Pathways in Plant Regeneration

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Enhancing Genetic Transformation

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Developmental Regulators (DEV Genes) | Overcome genotype recalcitrance by enhancing cell proliferation and shoot regeneration. | BBM/WUS2: Induces somatic embryogenesis in maize and sorghum [16].GRF4-GIF1 Chimera: Boosts regeneration in dicots (tomato, lettuce) and monocots (wheat, rice) [16] [18].WOX5: Improves transformation in recalcitrant wheat genotypes [16]. |

| Visual Reporter Genes | Enable rapid, non-destructive screening of transgenic events without specialized equipment. | RUBY: A triple-gene system producing red betalain pigments, effective in tomato and other species [18] [23].Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP): Requires UV light for detection [18] [20]. |

| Agrobacterium Strains | Vehicle for DNA delivery. Strain choice can impact transformation efficiency and plant health. | EHA105: Used for stable transformation in Jonquil and broomcorn millet, resulting in normal plant growth [20] [23].K599 (A. rhizogenes): Can induce abnormal growth (dwarfing, wrinkled leaves) in stable transformants [23]. |

| Culture Medium Additives | Improve the efficiency of callus growth and regeneration. | Acetosyringone: A phenolic compound that induces Agrobacterium's virulence genes during co-cultivation [20].Antioxidants (e.g., Activated Charcoal): Reduce tissue browning by adsorbing phenolic compounds [19]. |

Beyond Tissue Culture: Next-Generation Transformation Methodologies

This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting and methodological guidance for researchers using key morphogenic regulators—BABY BOOM (BBM), WUSCHEL (WUS2), and GRF-GIF chimeric proteins—to enhance genetic transformation in recalcitrant plant species. Overcoming regeneration recalcitrance is a major bottleneck in applying transgenic breeding and gene editing to many crops essential for global food security. These development regulators offer promising solutions by boosting plant regeneration efficiency, extending the range of transformable genotypes, and facilitating the application of new breeding technologies in ornamental, minor, and recalcitrant crops [24].

FAQs: Core Concepts and Applications

1. What are morphogenic regulators, and why are they important for transforming recalcitrant plants? Morphogenic regulators are plant transcription factors that control key developmental processes, such as embryogenesis and meristem formation. When expressed in tissue culture, they can dramatically enhance a plant's innate capacity to regenerate shoots or somatic embryos from transformed cells. This is crucial for recalcitrant species, where traditional hormone-based regeneration systems often fail or are extremely inefficient [24] [1].

2. How does the GRF-GIF chimeric protein differ from and improve upon individual GRF or GIF genes? The GRF-GIF chimera is a single gene encoding a fusion protein that combines a Growth-Regulating Factor (GRF) transcription factor with its GRF-INTERACTING FACTOR (GIF) cofactor. Research shows that the forced proximity of these two proteins in the chimera is significantly more effective at promoting regeneration than expressing the two genes separately on the same construct. In wheat, the chimera provided a 7.8-fold increase in regeneration efficiency over the control, vastly outperforming the individual genes [25].

3. Can these morphogenic regulators be used in dicot species, or are they limited to monocots? Yes, evidence shows these strategies can be successfully applied across species boundaries. The wheat GRF4-GIF1 chimera improved regeneration not only in monocots like wheat and rice but also in the dicot citrus. Furthermore, research specifically highlights the potential of using dicot-derived GRF-GIF chimeras to improve regeneration in dicot crops [25] [24].

4. What is a key advantage of using GRF-GIF for regeneration over traditional cytokinin-based methods? A significant advantage is that GRF-GIF can induce efficient wheat regeneration without the need for exogenous cytokinins in the culture medium. This not only simplifies the protocol but also facilitates the selection of transgenic plants without selectable markers, streamlining the production of edited plants [25].

5. How do BBM and WUS2 function together in transformation systems? BBM and WUS2 are often used in combination to induce direct somatic embryogenesis. BBM promotes a conversion from vegetative to embryonic growth, while WUS2 is critical for maintaining stem cell identity in the shoot meristem. Their combined and refined expression has been shown to alleviate pleiotropic effects and enable transformation in previously recalcitrant monocot genotypes [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Troubleshooting Low Regeneration Efficiency

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Few or no regenerated shoots | Suboptimal expression of morphogenic regulator | Optimize promoter choice (e.g., maize UBIQUITIN promoter); verify gene integration and expression levels [25]. |

| Repression of morphogenic regulator by native miRNA | Use miRNA-resistant versions of the genes (e.g., modify the GRF sequence to avoid silencing by miR396) [25]. | |

| Incorrect hormone balance in culture media | For non-GRF-GIF methods, titrate auxin-to-cytokinin ratio. Test different auxins (2,4-D, NAA) and cytokinins [4]. | |

| Slow or stunted regeneration | Plant defense response to Agrobacterium infection | Use antioxidant washes for explants; consider adding silver nitrate (ethylene inhibitor) or other pathogen response suppressors to the medium [4]. |

| Regeneration only in non-transformed cells | Severe stress from transformation and selection | Weaken the plant's immune system during co-cultivation (e.g., through virus-mediated silencing of defense genes); ensure selection pressure is not overly toxic [4]. |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Morphogenic Regulators

| Regulator | Typical Fold-Increase in Regeneration | Key Advantages | Reported Species |

|---|---|---|---|

| GRF4-GIF1 Chimera | 7.8x in wheat vs. control [25] | Fertile transgenic plants without defects; enables cytokinin-free regeneration; genotype-flexible [25] [26] | Wheat, rice, triticale, citrus [25] |

| BBM/WUS2 | High transformation in recalcitrant maize [24] | Induces direct somatic embryogenesis; effective in recalcitrant monocots [24] [1] | Maize, sorghum, other monocots [24] |

| GRF4 alone | ~3x in wheat vs. control (not significant) [25] | - | Wheat [25] |

| GIF1 alone | ~3x in wheat vs. control (not significant) [25] | - | Wheat [25] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Constructing a GRF-GIF Chimeric Expression Vector

This protocol outlines the creation of a GRF-GIF chimera for plant transformation, based on the work of Debernardi et al. [25].

Key Reagents:

- Source Genes: GRF (e.g., wheat GRF4) and GIF (e.g., wheat GIF1) coding sequences.

- Expression Vector: A binary vector containing a strong constitutive promoter (e.g., Maize Ubiquitin promoter).

- Enzymes: Restriction enzymes or reagents for seamless cloning (e.g., In-Fusion Snap Assembly Master Mix).

Methodology:

- Gene Fusion: Fuse the selected GRF and GIF coding sequences in-frame, linked by a short, flexible peptide spacer. The original study designed a construct where GIF1 was fused directly to GRF4 [25].

- Vector Assembly: Clone the resulting GRF-GIF chimeric sequence downstream of the chosen promoter in the binary vector.

- Transformation: Introduce the final vector into Agrobacterium tumefaciens for plant transformation.

Protocol 2: Agrobacterium-mediated Transformation of Wheat with GRF-GIF

This is a generalized workflow derived from the optimized protocol in the primary literature [25].

Workflow Diagram:

Key Steps and Technical Nuances:

- Explant Preparation: Isolate immature embryos (1.5-3.0 mm) from the plant. The GRF-GIF system is robust across a wider embryo size range and environmental conditions [25].

- Inoculation & Co-cultivation: Inoculate embryos with Agrobacterium strain carrying the GRF-GIF construct and co-cultivate for a standard duration.

- Callus Induction & Selection: Transfer embryos to callus-induction media containing appropriate antibiotics (e.g., to suppress Agrobacterium and select for transformed plant cells).

- Regeneration: A key advantage of GRF-GIF is the high-efficiency regeneration on media that may not require exogenous cytokinin hormones. This step is also accelerated compared to standard protocols [25] [26].

- Rooting and Acclimatization: Transfer regenerated shoots to rooting media, then gradually acclimate plantlets to greenhouse conditions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Transformation with Morphogenic Regulators

| Reagent | Function | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| GRF-GIF Chimera Plasmid | Key construct to enhance regeneration efficiency. | Plasmid with maize Ubi promoter driving wheat GRF4-GIF1; use miRNA-resistant GRF sequence to prevent silencing [25]. |

| BBM/WUS2 Expression Vectors | Induces direct somatic embryogenesis in recalcitrant species. | Often used as separate vectors or on a single construct with refined expression to minimize pleiotropy [24]. |

| In-Fusion Snap Assembly Master Mix | For seamless, ligation-independent cloning of constructs. | Preferred for high efficiency (>95% accuracy) and 15-minute reaction time; ideal for building chimeric genes [27]. |

| Competent E. coli Cells | For plasmid propagation and cloning. | Use strains like Stbl2 or Stbl4 for cloning unstable DNA (e.g., repeats); ensure high transformation efficiency (>108 cfu/µg) [28] [27]. |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens Strain | Vehicle for plant transformation. | Standard strains like EHA105 or GV3101; the GRF-GIF system has shown success with different protocols and genotypes [25] [1]. |

| Selection Agents | To identify successfully transformed plant cells. | Antibiotics (e.g., hygromycin) or herbicides; GRF-GIF can help reduce dependency on selectable markers [25] [1]. |

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Morphogenic Regulator Signaling and Function

This diagram illustrates the functional roles and interactions of BBM, WUS2, and GRF-GIF in the plant regeneration process.

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs for researchers conducting in planta transformation, a set of techniques that bypass traditional tissue culture to enable more efficient genetic transformation and gene editing in recalcitrant plant species.

Core Concepts and FAQs

What is in planta transformation and how does it differ from conventional methods?

In planta transformation refers to a heterogeneous group of techniques for achieving stable genetic transformation by directly introducing foreign DNA into intact plants or plant tissues with no or minimal tissue culture steps [6]. Unlike conventional methods that require generating and regenerating callus tissue under sterile conditions, in planta approaches target specific tissues like meristems, germline cells, or embryos, allowing transformed cells to develop directly into whole plants [6].

The conceptual framework defines in planta techniques by their avoidance of extensive tissue culture, characterized by short duration with limited medium transfers, technical simplicity with simple hormone compositions, and regeneration that occurs directly from a differentiated explant without a callus development stage [6].

Why is in planta transformation particularly valuable for recalcitrant species?

In planta transformation addresses a major bottleneck in plant biotechnology—transformation recalcitrance. Many commercially important and underutilized crops, especially perennial species and most legumes (excluding soybean, alfalfa, and Lotus japonicus), prove difficult or impossible to transform using established in vitro methods [1] [22] [29].

These techniques are often considered genotype-independent as they do not rely heavily on hormone supplementation and typically omit the callus regeneration step, making them less prone to somaclonal variations and more applicable to a wider range of genotypes within a species [6]. Their simple and affordable nature makes them particularly suited for minor crops and labs with limited resources [6].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Low or No Transformation Efficiency

Q: After conducting an in planta transformation experiment, I observe very few or no transformed plants. What could be causing this?

| Possible Cause | Recommendations for Optimization |

|---|---|

| Suboptimal delivery efficiency | - For Agrobacterium-mediated methods, ensure bacterial health and activate virulence machinery with acetosyringone [30].- Optimize the optical density (OD) of the Agrobacterium culture used for inoculation, as this can be system-specific [30].- For pollen transformation, consider efficiency of delivery methods (e.g., electroporation, particle bombardment) [22] [29]. |

| Poor regeneration of transformed cells | - For meristem transformation, ensure proper wounding to allow Agrobacterium access while preserving regenerative capacity [4].- Consider incorporating genes like WIND1 (wound-induced dedifferentiation) and IPT (cytokinin biosynthesis) to enhance shoot regeneration from wounded sites [31]. |

| Plant immune response | - Agrobacterium infection can trigger a strong immune response. Using antioxidants in co-culture media or selecting plant genotypes with reduced defense responses may improve efficiency [4]. |

| Incorrect developmental stage | - For floral dip, use young flowers at the correct developmental stage. For meristem targeting, use actively dividing tissues [6]. |

Problem: High Background or Non-Transformed "Escaper" Plants

Q: I get many plants that survive selection but are not transformed. How can I reduce these false positives?

| Possible Cause | Recommendations for Optimization |

|---|---|

| Ineffective selection pressure | - Optimize antibiotic or herbicide concentration for your specific plant species and method. Test selection agents on untransformed controls first.- Ensure selective agents are fresh and properly stored, as degradation (e.g., of ampicillin) can lead to satellite colony growth [28] [32]. |

| Insufficient T-DNA integration | - Ensure the Agrobacterium strain, binary vector, and plant genotype are compatible [30].- For large constructs (e.g., CRISPR/Cas9 cassettes), verify plasmid stability in Agrobacterium and use strains designed for large plasmids [30]. |

| Chimeric plants | - In planta methods can produce chimeras. Advance to the next generation (T1) and screen multiple progeny to identify stable, non-chimeric lines [1] [6]. |

Problem: Unstable DNA Integration or Unintended Mutations

Q: My transformed plants show unstable inheritance of the transgene or unexpected mutations. How can I address this?

| Possible Cause | Recommendations for Optimization |

|---|---|

| Complex T-DNA integration | - Agrobacterium-mediated transfer can sometimes create complex insertion loci. Use Southern blotting or long-read sequencing to characterize insertion sites in primary transformants.- Consider using transformation methods that typically yield lower-copy-number integrations, such as Agrobacterium-mediated vs. biolistics. |

| Unstable repetitive sequences | - CRISPR/Cas9 constructs with direct repeats may undergo recombination. Use Agrobacterium strains like Stbl2 or Stbl4 designed to stabilize such sequences [28]. |

| Somaclonal variation | - While in planta methods minimize this risk, some variation can still occur. Always compare multiple independent transformed lines to distinguish true transgenic phenotypes from random variations [6]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Floral Dip Method with Vacuum Infiltration

This protocol is adapted for species beyond Arabidopsis, such as some legumes and cereals [6].

Materials:

- Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 or similar, carrying the binary vector of interest.

- Plants with abundant young flowers and healthy buds.

- Infiltration medium: 5% sucrose, 0.05% Silwet L-77, half-strength Murashige and Skoog (MS) salts.

- Vacuum chamber and pump.

Procedure:

- Grow Agrobacterium in liquid YEP medium with appropriate antibiotics to an OD600 of 0.6-0.8.

- Pellet bacteria by centrifugation (5,000 × g for 10 min) and resuspend in infiltration medium to a final OD600 of 0.8-1.0.

- Place above-ground parts of potted plants with numerous young inflorescences into the bacterial suspension.

- Apply vacuum (250-500 mmHg) for 5-10 minutes, then slowly release. Ensure all tissues are submerged and infiltrated.

- Repeat infiltration after 5-7 days to increase transformation efficiency.

- After infiltration, lay plants on their sides, cover with transparent plastic or dome to maintain humidity, and keep in low light for 24 hours.

- Return plants to normal growth conditions. Grow until seeds mature, then harvest and dry.

- Surface-sterilize T1 seeds and plate on selective medium containing the appropriate antibiotic or herbicide.

Direct Meristem Transformation for Monocots

This method targets the shoot apical meristem (SAM) in mature embryos or seedlings and is applicable to perennial grasses and recalcitrant cereals [22] [29].

Materials:

- Mature seeds of the target species.

- Agrobacterium strain EHA105 or LBA4404 for monocots.

- Co-culture medium: MS salts, 2.0 mg/L 2,4-D, 100 µM acetosyringone, 0.8% agar.

- Selection medium: MS salts with appropriate selection agent.

Procedure:

- Sterilize mature seeds and germinate on moist filter paper for 24-48 hours.

- Excise the shoot apical meristem from germinated seedlings by making a longitudinal slice to expose the meristematic dome.

- Inoculate the wounded meristem with an Agrobacterium suspension (OD600 0.4-0.6) in liquid infection medium containing acetosyringone for 15-30 minutes.

- Blot dry and co-culture on solid co-culture medium for 2-3 days in the dark at 25°C.

- Transfer explants to selection medium containing antibiotics to suppress Agrobacterium and the appropriate selective agent for plant transformation.

- Allow shoots to develop directly from the meristem without an intervening callus phase. Subculture every 2 weeks.

- Elongate and root regenerated shoots on hormone-free medium containing the selection agent.

- Acclimate plantlets to greenhouse conditions and screen for transformation.

The following diagram illustrates the key workflow and biological pathways involved in this meristem transformation protocol:

Tissue Culture-Free Transformation Using Developmental Regulators

This novel system combines developmental regulator genes with CRISPR/Cas9 for direct gene editing without tissue culture [31].

Materials:

- Plant expression vectors containing WIND1 and IPT genes.

- CRISPR/Cas9 construct targeting gene of interest.

- Agrobacterium strain for plant transformation.

- Sterile seedlings or in vitro plantlets of target species.

Procedure:

- Clone the WIND1 (wound-induced dedifferentiation) and IPT (isopentenyl transferase) genes into appropriate expression vectors, preferably with inducible promoters.

- Combine with CRISPR/Cas9 construct in the same Agrobacterium strain or use co-transformation approaches.

- Wound the stem or leaf tissues of intact plants or seedlings using a sterile needle or blade.

- Immediately apply the Agrobacterium suspension directly to wounded sites.

- Induce gene expression if using inducible promoters (e.g., with β-estradiol or dexamethasone).

- Enclose treated plants to maintain high humidity around transformation sites.

- Within 2-4 weeks, observe shoot formation directly from wounded sites.

- Excise emerging shoots and root them on appropriate medium.

- Molecularly screen regenerated shoots for the presence of the gene edit and the absence of the transformation vector.

Quantitative Data and Efficiency Comparisons

Transformation Efficiency Across Methods and Species

The table below summarizes reported transformation efficiencies for various in planta methods across different plant species, demonstrating the variability and potential of these techniques.

| Species | Delivery Method | Plant Tissue | Efficiency (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis thaliana | Floral dip | Young flowers | 0.5 - 3.0% (T1 seeds) | [6] |

| Barley (Hordeum vulgare) | VIGE | Leaf tissues (Cas9-expressing) | 17% - 35% (T0) | [22] [29] |

| Barley (Hordeum vulgare) | Biolistics (iPB-RNP) | Mature embryos | 1% - 4.2% (T0) | [22] [29] |

| Maize, Wheat | Haploid induction (HI-Edit) | Pollen/Egg | 0% - 8.8% (T0) | [22] [29] |

| Perennial ryegrass | SAAT | Seed, meristem tip | 14.2% - 46.65% (T0) | [22] [29] |

| Rice (Oryza sativa) | Agrobacterium-mediated | Coleoptile | 8.4% (T0) | [22] [29] |

| Rice (Oryza sativa) | Agrobacterium-mediated | Mature embryos | 40% - 43% (T0) | [22] [29] |

| Rice (Oryza sativa) | Agrobacterium-mediated | Seedlings | 9% (T0) | [22] [29] |

| Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) | Agrobacterium-mediated | Seedlings | 26% - 38% (T0) | [22] [29] |

Comparison of Transformation Recalcitrance in Legumes

The table below highlights the challenge of transformation recalcitrance in legumes, which motivates the development of in planta approaches.

| Plant Name | Type | Transformation Efficiency (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nicotiana tabacum (Tobacco) | Susceptible (>15%) | 100 | [1] |

| Lotus japonicus | Susceptible (>15%) | 94 | [1] |

| Alfalfa | Susceptible (>15%) | 90 | [1] |

| Soybean | Susceptible (>15%) | 34.6 | [1] |

| Vigna mungo (Black gram) | Recalcitrant (<15%) | 3.8 - 7.6 | [1] |

| Vigna radiata (Mung bean) | Recalcitrant (<15%) | 1.49 - 4.2 | [1] |

| Vigna unguiculata (Cowpea) | Recalcitrant (<15%) | 3.09 | [1] |

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details essential materials and their functions for establishing in planta transformation protocols.

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Agrobacterium Strains | GV3101, EHA105, LBA4404, AGL1 | Delivery of T-DNA; strain choice affects host range and efficiency [30]. |

| Developmental Regulators | WIND1, IPT, Bbm, Wus2 | Enhance regeneration potential; promote shoot formation from somatic cells [31]. |

| Virulence Inducers | Acetosyringone | Phenolic compound that activates Agrobacterium virulence genes during co-culture [30]. |

| Surfactants | Silwet L-77, Pluronic F-68 | Reduce surface tension of infiltration media, improving tissue penetration [6]. |

| Antibiotics (Bacterial) | Rifampicin, Gentamicin, Spectinomycin | Select for Agrobacterium strain and maintain binary/Ti plasmids [30]. |

| Selection Agents (Plant) | Kanamycin, Hygromycin, Phosphinothricin (Basta) | Select for transformed plant cells; choice depends on vector selectable marker [28] [32]. |

| Growth Media | YEP, LB, SOC Medium, MS Medium | Support Agrobacterium growth (YEP, LB, SOC) and plant development (MS) [32] [30]. |

Advanced Technical Considerations

Understanding and Mitigating Plant Immune Responses

Successful in planta transformation requires navigating the plant's innate immune system. Agrobacterium infection triggers pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP)-triggered immunity, which can be a significant barrier to transformation [4]. Research indicates that silencing key immunity-related genes such as Isochorismate Synthase (involved in salicylic acid biosynthesis) or Nonexpresser of Pathogenesis-Related Genes 1 can increase transgene expression following Agrobacterium infiltration [4]. Additionally, maintaining stable pH during co-culture has been shown to suppress defense signaling and enhance transient expression [4].

Optimizing DNA Delivery and Integration

For CRISPR/Cas9 applications, delivery of large constructs (>10 kb) can be challenging. While chemical transformation methods have been successfully used for plasmids up to 24 kb in Agrobacterium, ensuring plasmid stability is crucial [30]. Unwanted plasmid homologous recombination in Agrobacterium occurs frequently, especially with constructs containing repeated elements or recombinases [30]. Using specialized strains and minimizing repeated sequences in constructs can help maintain plasmid integrity.

The following diagram illustrates the molecular interplay between the plant immune system and Agrobacterium during transformation, highlighting key targets for optimization:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the main advantages of using auxotrophicAgrobacteriumstrains for plant transformation?

Auxotrophic strains offer two primary advantages that address key challenges in plant transformation:

- Control of Bacterial Overgrowth: After co-cultivation with plant explants, these strains cannot proliferate on standard plant culture media unless supplemented with specific metabolites they cannot synthesize. This drastically reduces Agrobacterium overgrowth, which can otherwise kill regenerating plant tissues [33]. This reduces or eliminates the need for high doses of antibiotics, which are costly and can be phytotoxic [34] [33].

- Enhanced Biosafety: Auxotrophic strains are "biocontained." They require laboratory-supplied metabolites to survive and are less likely to persist in natural environments like soil or on plants, mitigating the environmental risk of accidental release of genetically modified bacteria [35] [33].

How do ternary vector systems improve transformation efficiency in recalcitrant plants?

Ternary vector systems enhance transformation by providing extra copies of key virulence (vir) genes. Unlike standard binary vectors, this system uses a T-DNA binary vector alongside a separate, compatible "helper" plasmid carrying additional vir genes [34] [36]. This boosts the activity of the Agrobacterium's Type IV Secretion System, leading to more efficient T-DNA transfer into plant cells. This has resulted in 1.5- to 21.5-fold increases in stable transformation efficiency in previously difficult-to-transform species like maize, sorghum, and soybean [36].

My transgenic plants show abnormal growth phenotypes after usingA. rhizogenesstrain K599. What is the cause and how can I avoid this?

Abnormal growth such as dwarfism, wrinkled leaves, or tentacle-like protrusions is a known issue when using wild-type or poorly disarmed A. rhizogenes strains for stable transformation. These phenotypes are caused by the integration and expression of root-inducing (rol) genes from the Ri plasmid's T-DNA, which disrupt normal plant hormone signaling [23]. To avoid this:

- For stable transformation of whole plants, use fully disarmed strains of A. tumefaciens (e.g., EHA105, LBA4404) instead of A. rhizogenes [23].

- Reserve A. rhizogenes K599 for applications where hairy root generation is the desired outcome, such as the study of root biology or the creation of composite plants [23].

What are the latest methods for engineering newAgrobacteriumstrains?

Traditional methods like homologous recombination and transposon mutagenesis are being supplemented by more precise modern techniques:

- CRISPR-Based Editing: CRISPR-Cas systems can introduce targeted double-strand breaks for gene knockouts, such as creating auxotrophic mutants by disrupting the

thyAgene [35] [34]. - INTEGRATE System: This CRISPR RNA-guided transposase system allows for precise, marker-free insertion of DNA fragments without creating double-strand breaks, enabling tasks like targeted gene knockouts and large-fragment deletions to "disarm" wild strains [35].

- Base Editing: This technique allows for direct, single-nucleotide conversion (e.g., C to T) to create loss-of-function mutations without cleaving the DNA backbone, though off-target effects remain a concern [35].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: PersistentAgrobacteriumOvergrowth After Co-cultivation

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Check | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Ineffective antibiotics | Check if the antibiotic is correct for your Agrobacterium strain and if the stock solution is active. | - Use a combination of antibiotics (e.g., timentin or augmentin).- Switch to an auxotrophic strain (e.g., EHA105Thy-). Omit thymidine from the regeneration media to prevent bacterial growth [34] [33]. |

| Insufficient antibiotic concentration or exposure time | Observe if overgrowth is uniform or localized. | - Increase antibiotic concentration in wash and media steps.- Ensure explants are thoroughly washed after co-cultivation. |

| Strain is not properly disarmed | Test the strain's ability to form galls on a susceptible host plant. | Use a verified disarmed strain from a reputable repository. |

Problem: Low Transformation Efficiency in a Recalcitrant Monocot Species

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Check | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inefficient T-DNA delivery | Perform a transient GUS or GFP assay. Low signal indicates delivery issues. | - Adopt a ternary vector system. Introduce a helper plasmid like pKL2299A, which carries extra virG, virB, virC, virD, virE, virJ, and virA genes from hypervirulent plasmid pTiBo542 [34] [36]. |

| Poor Agrobacterium virulence induction | Check that acetosyringone is added to the co-cultivation medium. | - Optimize the concentration and timing of acetosyringone application.- Ensure the co-cultivation medium is at an acidic pH (~5.2) to induce the vir genes [4]. |

| Suboptimal explant tissue or genotype | Review literature for transformable genotypes of your species. | - If possible, switch to a more transformable cultivar (e.g., wheat cv. 'Fielder' or 'Bobwhite') [4].- Test different explant types (e.g., immature embryos vs. callus). |

Problem: Low Transient Transformation Efficiency in a Novel Dicot Species

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Check | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Strong plant immune response | Look for tissue necrosis or browning within 1-2 days of infiltration. | - Add a surfactant like Silwet L-77 to the infiltration buffer [37].- Consider using plant defense suppressor genes (e.g., silencing Nonexpressor of Pathogenesis-Related Genes 1), though this is more advanced [4]. |

| Suboptimal infiltration technique | Observe if the infiltrated area becomes water-soaked. | - For seedlings, use vacuum infiltration (e.g., 0.05 kPa for 5-10 min) or a simple immersion method [37].- For leaves, use a needleless syringe. Ensure the OD~600~ of the Agrobacterium culture is optimized (often ~0.8) [37]. |

| Poor T-DNA transfer | Test the same Agrobacterium strain on a susceptible plant like Nicotiana benthamiana. | - Screen different Agrobacterium strains (e.g., GV3101, EHA105) to find the most effective one for your plant species [38] [37]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Generating a Thymidine Auxotrophic Strain Using INTEGRATE

This protocol uses the CRISPR-guided transposase system INTEGRATE for precise gene insertion to disrupt the thyA gene [35] [34].

Key Reagents:

- INTEGRATE Plasmid: Contains the Cas-transposition operon, crRNA targeting the

thyAlocus, and a donor mini-Tn with a selectable marker. - Agrobacterium Strain: The strain to be engineered (e.g., LBA4404).

- Media: LB with appropriate antibiotics, AB minimal medium, MS medium with and without thymidine.

Methodology:

- Target Site Selection: Design a crRNA spacer that targets a site within the

thyA(thymidylate synthase) gene on the Agrobacterium chromosome. - Cloning and Transformation: Clone the spacer into the INTEGRATE plasmid and introduce the final plasmid into the target Agrobacterium strain via electroporation.

- Screening for Targeted Insertion: Culture transformed bacteria on selective media. Screen colonies by PCR using primers flanking the

thyAtarget site and internal to the inserted cargo to confirm precise integration. - Verification of Auxotrophy:

- Inoculate the candidate mutant in liquid AB minimal medium without thymidine. No growth should be observed.

- As a control, inoculate the same strain in AB minimal medium supplemented with thymidine (e.g., 100 mg/L). Growth should be restored.

- Plate the strain on MS medium with and without thymidine. Growth should only occur on supplemented plates [33].

- Vector Eviction: Use the

sacBcounterselection marker on the INTEGRATE plasmid to cure the plasmid from the confirmed auxotrophic strain, resulting in a marker-free mutant [35].

The following diagram illustrates the key steps and verification process for creating an auxotrophic Agrobacterium strain using the INTEGRATE system.

Protocol: Optimizing a Ternary Vector System for Maize Transformation

This protocol describes how to employ a ternary vector system to improve stable transformation efficiency in maize [34].

Key Reagents:

- T-DNA Binary Vector: Contains your gene of interest and plant selection marker.

- Ternary Helper Plasmid: A compatible plasmid carrying additional vir genes (e.g., pKL2299A, which includes

virAfrom pTiBo542) [34]. - Agrobacterium Strain: A disarmed, auxotrophic strain like EHA105Thy-.

- Plant Material: Immature embryos of a transformable genotype (e.g., B104).

Methodology:

- Strain Preparation: Co-transform the T-DNA binary vector and the ternary helper plasmid into the auxotrophic Agrobacterium strain. Select for both plasmids on media supplemented with thymidine and the appropriate antibiotics.

- Culture and Induction: Grow the transformed Agrobacterium to mid-log phase in induction medium containing acetosyringone to activate the vir genes.

- Co-cultivation: Infect immature maize embryos with the Agrobacterium culture and co-cultivate on solid medium for several days.

- Selection and Regeneration: Transfer co-cultivated embryos to regeneration media containing thymidine (to support auxotrophic Agrobacterium during initial recovery) and a plant selection agent (e.g., hygromycin). After the first transfer, omit thymidine to suppress bacterial growth in subsequent steps.

- Efficiency Calculation: Calculate transformation frequency as the percentage of co-cultivated embryos that produce transgenic events.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Auxotrophic Strains | Reduces overgrowth and improves biosafety by requiring metabolite supplementation. | - EHA105Thy‑: Thymidine auxotroph for monocot transformation [34].- EHA105hisD−/leuA−: Histidine/leucine auxotrophs for dicot transformation [33]. |

| Ternary Helper Plasmids | Boosts T-DNA delivery by providing extra copies of virulence (vir) genes. | - pKL2299A: Contains virA from pTiBo542; improves maize transformation [34].- General ternary helpers with virG, virB, virC, virD, virE, virJ operons [36]. |

| Novel Engineering Tools | Enables precise genomic modification of Agrobacterium itself. | - INTEGRATE System: For precise, marker-free DNA insertion [35].- CRISPR Base Editors: For targeted single-nucleotide changes [38] [35]. |

| Virulence Inducers | Activates the Agrobacterium T-DNA transfer machinery. | - Acetosyringone: A phenolic compound added to co-cultivation media [35].- Acidic pH (∼5.2): Essential for optimal vir gene induction [4]. |

| Surfactants | Enhances contact and infiltration of Agrobacterium into plant tissues. | - Silwet L-77: Critical for high-efficiency transient transformation in sunflower and other species [37]. |

The following diagram illustrates how these key reagents work together in an optimized Agrobacterium-mediated transformation system, highlighting the roles of auxotrophic strains and ternary vectors.

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: What are the main advantages of using in planta transformation methods over traditional tissue culture-based approaches for recalcitrant species?

A1: In planta transformation methods offer several key advantages for transforming recalcitrant plant species, as outlined in the table below.

Table 1: Advantages of In Planta Transformation Methods

| Feature | Traditional Tissue Culture | In Planta Transformation |

|---|---|---|

| Genotype Dependence | Often high; limited to specific, transformable genotypes [22] [39] | Significantly reduced; more genotype-independent [22] [39] |

| Process Duration | Long (3-4 months); requires callus induction and regeneration [40] [41] | Shorter (5-7 weeks); can bypass the callus stage [40] [39] |

| Technical Complexity | High; requires optimized media and sterile culture [41] | Simplified; can bypass tissue culture, reducing labor and infrastructure needs [22] [42] |

| Somaclonal Variation | Possible due to extended culture period [41] | Less likely as it minimizes or avoids a dedifferentiated callus phase [42] |

Q2: Our lab is working with a perennial grass that is recalcitrant to transformation. We have difficulty accessing immature embryos for explants. What alternative methods and explants can we use?

A2: This is a common challenge with perennial species. The following troubleshooting guide summarizes alternative strategies and their applications.