Comparative Efficiency of Plant Genetic Transformation Methods: A Guide for Researchers and Developers

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the efficiency, applications, and future trajectories of modern plant genetic transformation techniques.

Comparative Efficiency of Plant Genetic Transformation Methods: A Guide for Researchers and Developers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the efficiency, applications, and future trajectories of modern plant genetic transformation techniques. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and biotechnology professionals, it systematically compares established methods like Agrobacterium-mediated transformation and biolistics with emerging tissue culture-free strategies. We explore the foundational principles of plant regeneration, delve into specific methodological protocols, and address key bottlenecks through advanced optimization strategies such as developmental regulators and improved gene gun designs. A critical validation and comparative analysis section equips the reader to select the most efficient method for their specific project, with conclusions highlighting the transformative potential of these technologies for accelerating crop improvement and biopharmaceutical production.

The Bedrock of Plant Genetic Engineering: Core Principles and Regeneration Biology

Defining Plant Genetic Transformation and Its Role in Crop Improvement

Plant genetic transformation is a foundational biotechnology that enables the precise introduction of genes with known functional characteristics—such as high yield potential, stress resistance, disease and pest tolerance, and enhanced nutritional profiles—into target plants [1]. This process allows recipient plants to acquire novel agricultural traits while preserving their original genetic foundations, representing a significant advancement over traditional breeding methods [1]. Since the first genetically modified crop was successfully generated in 1983, researchers have developed over 200 transgenic plants spanning 35 botanical families, including major crops like rice, corn, wheat, tomatoes, cotton, and soybeans [1]. The global significance of this technology is reflected in its market trajectory, valued at $1.58 billion in 2024 and projected to reach $3.03 billion by 2035, demonstrating its expanding role in addressing agricultural challenges [2].

The advancement of plant regeneration technology is critical for addressing complex and dynamic climate challenges, ultimately ensuring global agricultural sustainability [3]. Genetic transformation technologies have become indispensable tools for both fundamental research and applied crop improvement, enabling scientists to elucidate gene functions and rapidly develop varieties with enhanced agronomic traits [1] [4]. As the global population continues to grow and climate change introduces new production constraints, these technologies offer promising pathways to develop crops with improved resilience, productivity, and nutritional quality [5].

Fundamental Principles and Methodologies of Plant Genetic Transformation

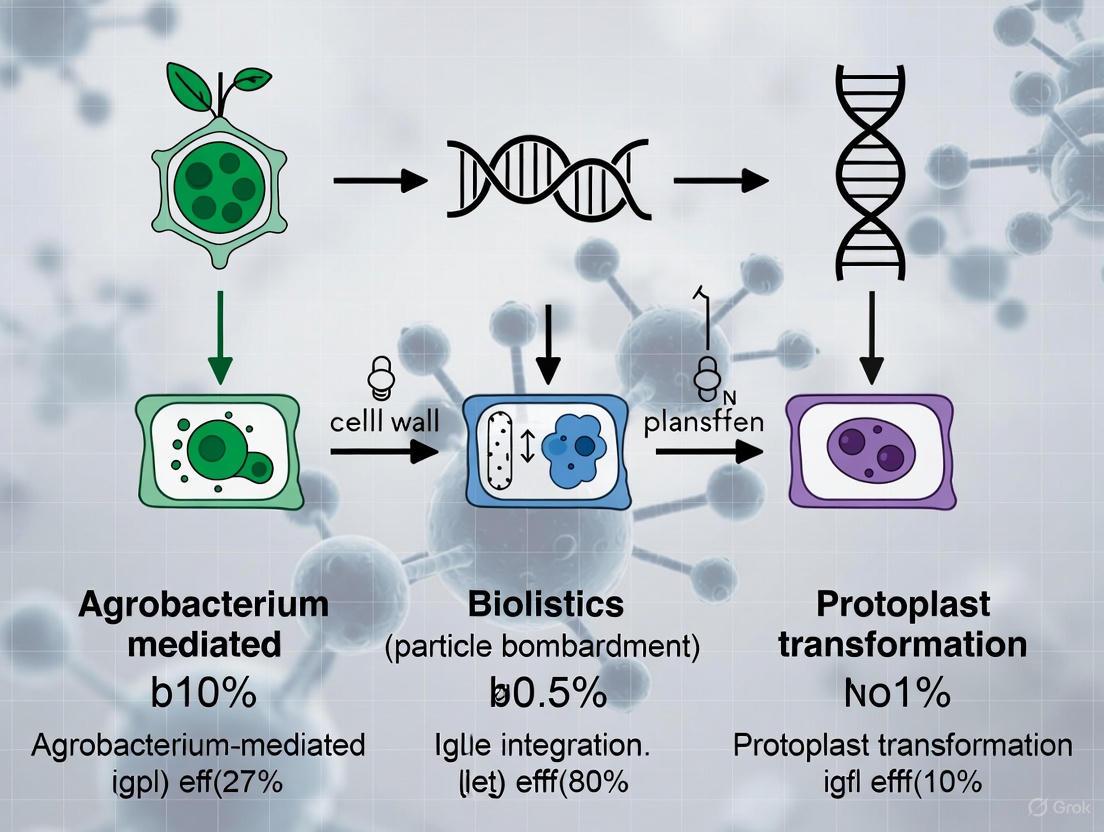

Classification of Transformation Methods

Plant genetic transformation methodologies can be broadly classified into two primary categories: direct gene transfer methods and bio-mediated transformation methods [1]. Direct gene transfer includes techniques such as microprojectile bombardment (gene gun), protoplast methods, liposome-mediated transfer, the pollen tube pathway, electroshock conversion, and PEG-mediated transformation [1]. Among these, microprojectile bombardment represents the most prominent direct transfer method, where DNA-coated metal particles are physically propelled into plant cells [4]. This approach is particularly valuable for species and genotypes that are less susceptible to biological transformation methods, though it often results in higher transgene copy numbers and increased instances of gene rearrangement [4].

Bio-mediated transformation predominantly utilizes biological vectors such as Agrobacterium tumefaciens and plant viruses to facilitate gene transfer [1]. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation has emerged as the preferred method for many plant species due to its simplicity, low cost, high transformation efficiency, and tendency to produce transgenic plants with lower transgene copy numbers and greater stability [1] [6]. This natural gene transfer mechanism exploits the soil bacterium's ability to transfer a segment of its DNA (T-DNA) into the host plant genome, a process that has been refined and optimized for laboratory transformation over several decades [1] [4].

The Centrality of Plant Regeneration

A fundamental prerequisite for successful genetic transformation is the establishment of a high-frequency plant regeneration system [1]. Regeneration describes the process by which plant tissues or organs repair and replace themselves following damage or environmental stress, a remarkable capability that finds extensive application in agricultural and horticultural techniques including cutting propagation, grafting, and tissue culture methodologies [1]. The concepts of cellular totipotency and pluripotency serve as the cytological foundation of plant regeneration, wherein somatic plant cells can be reprogrammed through hormonal interactions to develop into independent plants or organs via cell division and differentiation [1].

Higher plants regenerate through meristematic tissues, primarily the shoot apical meristem (SAM), root apical meristem (RAM), and lateral meristems [1]. These meristematic stem cells maintain their population through cell division while simultaneously differentiating into diverse tissue and organ cell types, representing the fundamental production source for complex biological structures in higher plants [1]. Contemporary research has identified specific classes of genes that actively promote plant regeneration during transformation processes, enabling the development of plant materials with heightened genetic transformation efficiency [1].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Plant Genetic Transformation Techniques

| Method | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agrobacterium-mediated | Uses A. tumefaciens to transfer T-DNA to plant cells [1] | Simple, low cost, high efficiency, low transgene copy number [6] | Genotype-dependent, low efficiency in some species [7] | Dicot transformation, stable transgene integration [1] |

| Particle Bombardment | DNA-coated metal particles propelled into plant cells [4] | Species-independent, no vector requirements [4] | High equipment cost, complex integration patterns [4] | Monocot transformation, organelle transformation [4] |

| Pollen-tube Pathway | Exogenous DNA introduced via pollen tube after pollination [1] | Avoids tissue culture, technically simple [1] | Low efficiency, limited reproducibility [1] | Cotton, melon, soybean transformation [1] |

| Protoplast Transformation | Direct DNA uptake by plant cells without cell walls [1] | High transformation frequency, synchronous treatment [1] | Difficult regeneration, genotype limitations [1] | Transient expression studies, single-cell analysis [1] |

Comparative Analysis of Major Transformation Methods

Agrobacterium-mediated Transformation

Agrobacterium-mediated transformation has become the most widely used method for plant genetic engineering, with approximately 85% of transgenic plants obtained using this approach [4]. The process begins with the recognition of plant signals by Agrobacterium, followed by bacterial attachment to wounded plant tissue and the subsequent transfer of T-DNA from the bacterium to the host plant genome [6]. Successful infection depends on both plant genotypes and Agrobacterium strains, with significant variation observed among different species and varieties [6].

The efficiency of Agrobacterium-mediated transformation is influenced by numerous factors, including explant type, Agrobacterium concentration, co-cultivation time, and medium composition [4]. Optimization studies have demonstrated that collecting Agrobacterium at a concentration of OD₆₅₀ = 0.6 and using a suspension medium containing dithiothreitol to infect half-seed cotyledonary explants can achieve infection efficiencies exceeding 96% [4]. Furthermore, the addition of phenolic compounds like acetosyringone has been found essential for induction of the virulence genes, while antioxidant reagents such as L-cysteine and dithiothreitol improve T-DNA delivery by inhibiting the activity of plant pathogen-response and wound-response enzymes [6].

Recent innovations have focused on enhancing Agrobacterium-mediated transformation through the use of auxiliary solutions. One study demonstrated that an Agrobacterium Auxiliary Solution (AAS) containing Silwet L-77 and hormone mixtures significantly improved hairy root transformation rates in soybean [7]. This combination increased total root and cotyledon transformation efficiencies compared to control treatments, highlighting the importance of chemical enhancers in optimizing transformation protocols [7].

Particle Bombardment and Direct DNA Transfer Methods

Particle bombardment, also known as biolistics or the gene gun approach, represents a physically-mediated transformation method that involves coating micron-sized gold or tungsten particles with DNA and accelerating them into plant cells using high-pressure helium gas [4]. This technique offers the significant advantage of being less constrained by plant genotype or species barriers compared to Agrobacterium-mediated methods, making it particularly valuable for transforming cereals and other species that have historically shown resistance to Agrobacterium infection [4].

The particle bombardment method does not require vector-specific sequences for DNA integration and enables the transformation of organelles, including chloroplasts and mitochondria, which is more challenging with biological vectors [4]. However, this approach typically results in more complex integration patterns, including higher transgene copy numbers and increased instances of gene rearrangement [4]. The equipment costs are substantially higher than Agrobacterium-based methods, and the process often produces more transgenic plants with silencing or unstable expression of the introduced genes due to complex integration loci [4].

Emerging and Specialized Transformation Techniques

Pollen-tube pathway transformation represents a unique direct DNA transfer method that utilizes the natural pathway of pollen tube growth to introduce exogenous genes into fertilized embryos [1]. First demonstrated in the 1970s, this technique involves injecting foreign DNA into the ovary after pollination, allowing the pollen tube to serve as a conduit for the DNA to enter the fertilized egg cell [1]. The major advantage of this approach is its bypass of the complex tissue culture process, making the technology relatively simple and accessible without requiring sophisticated laboratory facilities [1]. This method has been successfully applied to important crops including cotton, melon, soybean, and wheat, with transformation efficiencies reaching up to 2.54% in optimal conditions [1].

More recently, nanoparticle-mediated transformation has emerged as a promising alternative to conventional methods, though it was not specifically detailed in the search results. Similarly, floral dip methods, widely used in Arabidopsis transformation, represent another Agrobacterium-based approach that avoids tissue culture by directly infecting developing flowers.

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Transformation Efficiencies Across Methods and Species

| Plant Species | Transformation Method | Efficiency Range (%) | Key Factors Influencing Efficiency | Optimal Explant Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soybean [6] [4] | Agrobacterium-mediated | 0.21-10% | Genotype, GA and ZR levels, MeJA content [6] | Cotyledonary nodes [4] |

| Soybean [7] | Hairy root (A. rhizogenes) | 30-60% (cotyledon), up to 80% (stem) | Auxiliary solution, vector size [7] | Cotyledons, hypocotyls [7] |

| Rice [4] | Agrobacterium-mediated | Up to 23% | Genotype, selection system [4] | Immature embryos [4] |

| Maize [4] | Agrobacterium-mediated | 30-40% | Genotype, embryo quality [4] | Immature embryos [4] |

| Paphiopedilum Maudiae [1] | Pollen-tube pathway | 2.54% | Developmental stage, DNA delivery timing [1] | Ovules [1] |

Experimental Data: Method Efficiencies and Optimization Protocols

Soybean Transformation Efficiency Across Genotypes

Comparative studies have revealed significant variation in transformation efficiency among different soybean genotypes, highlighting the genotype-dependent nature of genetic transformation technologies [6]. Research evaluating ten soybean cultivars demonstrated dramatic differences in transformation efficiency, with high-efficiency genotypes like Williams 82, Shennong 9, and Bert achieving transformation rates of 6.71%, 5.32%, and 5.13% respectively, while low-efficiency genotypes such as General, Liaodou 16, and Kottman showed transformation efficiencies below 1% [6]. These differences in transformability were correlated with specific physiological and molecular factors, including hormone levels, gene expression patterns, and enzyme activities [6].

High-efficiency genotypes exhibited higher gibberellin (GA) levels and increased expression of soybean GA20ox2 transcripts, along with higher zeatin riboside (ZR) content and DNA quantity, and relatively higher expression of soybean IPT5, CYCD3, and CYCA3 genes [6]. Conversely, these genotypes showed lower methyl jasmonate (MeJA) content, polyphenol oxidase (PPO) activity, and peroxidase (POD) activity, along with reduced expression of OPR3, PPO1, and PRX71 genes [6]. These findings suggest that GA and ZR function as positive plant factors for Agrobacterium-mediated soybean transformation by facilitating germination and growth and increasing the number of cells in the DNA synthesis cycle, respectively [6]. Meanwhile, MeJA, PPO, POD, and abscisic acid (ABA) act as negative plant factors by inducing defense reactions and repressing germination and growth [6].

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Agrobacterium-mediated Soybean Transformation

An optimized protocol for Agrobacterium-mediated soybean transformation has been developed through systematic investigation of factors affecting infection and regeneration efficiency [4]. The following represents a detailed methodology for achieving high transformation efficiency in soybean:

Explant Preparation and Bacterial Infection:

- Surface-sterilize mature soybean seeds and imbibe for approximately 24 hours to obtain "half-seed" cotyledonary explants [4].

- Prepare Agrobacterium suspension by collecting bacteria at logarithmic growth phase (OD₆₅₀ = 0.6) and resuspending in infection medium containing 154.2 mg/L dithiothreitol [4].

- Infect explants by immersion in Agrobacterium suspension for 15-30 minutes with gentle agitation [7].

Co-cultivation and Selection:

- Transfer infected explants to co-cultivation medium with their adaxial side facing upward [4].

- Co-cultivate for 5 days in darkness at 22-25°C to allow T-DNA transfer and initial integration [4].

- Transfer explants to shoot induction medium containing appropriate selection agents (e.g., phosphinothricin at 5 mg/L) to inhibit growth of non-transformed tissues [6].

Shoot Elongation and Rooting:

- For shoot elongation, transfer explants with developing shoots to medium containing optimal hormone combinations—specifically 1.0 mg/L GA₃ and 0.1 mg/L IAA—which has been shown to increase elongation rates by 11-18% compared to standard protocols [4].

- Individual elongated shoots are subsequently transferred to rooting medium containing auxins such as IBA or NAA to promote root development [4].

- Finally, established plantlets are acclimatized to greenhouse conditions and grown to maturity for seed production [4].

Molecular Confirmation: Putative transgenic plants are verified through multiple methods including GUS histochemical staining, PCR analysis, herbicide painting (for herbicide resistance genes), and absolute quantification PCR to determine transgene copy number [4].

Successful plant genetic transformation requires specific reagents, vectors, and biological materials optimized for different plant species and transformation methods. The following toolkit summarizes critical components referenced in the search results:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Plant Genetic Transformation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application | Optimization Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agrobacterium Strains | EHA105, K599, Ar. Qual [7] | T-DNA delivery to plant cells | Strain selection affects host range and efficiency [7] |

| Vector Systems | pAGM4673, pTOPO-Blunt, Ruby vectors [7] | Gene cloning and expression | Smaller vectors (e.g., GFP) show higher efficiency [7] |

| Selection Agents | Phosphinothricin (5 mg/L), Antibiotics [6] | Selection of transformed tissues | Concentration optimization critical for regeneration [6] |

| Phenolic Inducers | Acetosyringone (40 mg/L) [7] | Vir gene induction in Agrobacterium | Essential for transformation competence [6] |

| Hormonal Supplements | GA₃ (1.0 mg/L), IAA (0.1 mg/L), 6-BA [4] [7] | Regulate plant regeneration | Optimal combinations improve shoot elongation [4] |

| Antioxidants | Dithiothreitol (154.2 mg/L), L-cysteine [4] | Suppress plant defense responses | Improve T-DNA delivery [6] |

| Surfactants | Silwet L-77 (100 μL/L) [7] | Enhance tissue penetration | Component of auxiliary solutions [7] |

Current Innovations and Future Perspectives

Advanced Genome Editing Tools

The field of plant genetic transformation is being revolutionized by CRISPR-based genetic editing technologies, which have rapidly become the most widely used tools in genome engineering due to their accuracy, cost-effectiveness, and ease of implementation [8] [2]. Comparative studies have evaluated the efficiency and specificity of Cas nucleases from different bacterial species, including Cas9 from Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9) and Staphylococcus aureus (SaCas9), as well as Cas12a from Francisella novicida and Lachnospiraceae bacterium [8]. These studies have found that SaCas9 is comparatively most efficient at inducing mutations, and that "high-fidelity" variants of Cas9 can effectively reduce off-target mutations in plants [8].

Innovations around CRISPR 2.0 and base editing technologies are gaining momentum, ushering in the next wave of biologically engineered products [2]. Base editing enables precise nucleotide changes without creating double-strand breaks in DNA, offering greater precision and potentially higher efficiency for specific applications [2]. Furthermore, the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning in genomic research is playing an increasingly important role in identifying gene-editing targets, predicting off-target effects, and modeling disease pathways, thereby making crop improvement programs more efficient and less risky [2].

Hormonal Regulation and Signaling Pathways

Recent research has elucidated the critical role of hormonal networks in regulating plant regeneration and transformation efficiency [3] [9]. Studies on bolting and flowering in various plant species, including leaf lettuce and Saposhnikovia divaricata, have demonstrated that plant hormone signal transduction pathways are decisive factors in controlling developmental transitions [10] [9]. In leaf lettuce, silencing of the serine/threonine protein kinase (STPK) gene affected bolting through modifications in auxin (IAA), gibberellin (GA3), and abscisic acid (ABA) contents [10]. Similarly, transcriptome analysis of Saposhnikovia divaricata identified auxin-related genes IAA and TIR1 as key regulators in the bolting and flowering process [9].

These findings highlight the intricate hormonal crosstalk that underlies plant development and regenerative capacity. The antagonistic relationships between hormones—such as ABA acting as an antagonist to GA [6]—directly impact the efficiency of transformation protocols, particularly during the critical stages of shoot induction and elongation [6] [4]. Future transformation protocols will likely incorporate more sophisticated hormonal manipulations based on improved understanding of these signaling networks.

Addressing Current Challenges and Future Directions

Despite significant advancements, plant genetic transformation continues to face several formidable challenges. Genotype-dependent transformation efficiency remains a major constraint, particularly for commercially valuable elite cultivars that are often recalcitrant to standard transformation protocols [6] [7]. Additionally, regulatory scrutiny and ethical concerns often slow the deployment of gene-edited crops, particularly in certain regions with restrictive policies toward genetically modified organisms [2] [5]. The high costs of research and development, coupled with intellectual property complexities, present additional barriers to widespread adoption of transformation technologies [2].

Future research directions will likely focus on developing genotype-independent transformation systems through the identification and utilization of regeneration-promoting genes [1]. The application of single-cell and spatial transcriptome technologies promises to provide unprecedented insights into the molecular foundations of plant regeneration and cellular totipotency [3] [1]. Furthermore, the emergence of synthetic biology approaches combining engineering principles with biological design is opening new frontiers in the creation of plants with novel functions, potentially expanding the capabilities of crop improvement beyond traditional agronomic traits [2] [5].

As these technologies continue to evolve, plant genetic transformation will play an increasingly vital role in global efforts to ensure food security, enhance nutritional quality, and develop sustainable agricultural systems capable of withstanding the challenges of climate change and population growth [3] [5]. The ongoing refinement of transformation methodologies will enable more precise and efficient genetic modifications, accelerating the development of next-generation crops with improved productivity, resilience, and value-added traits.

Cellular potency, the capacity of a single cell to differentiate into various cell types, establishes the fundamental framework for regeneration in multicellular organisms. This potency exists on a spectrum, with totipotency and pluripotency representing its most powerful states. In mammals, totipotency is a transient characteristic of the earliest embryonic cells, such as the zygote and early blastomeres (up to the 4-cell stage in humans), enabling them to generate an entire organism, including both embryonic and extraembryonic tissues like the placenta [11] [12]. Following several cell divisions, these totipotent cells transition into a pluripotent state. Pluripotent cells, found in the inner cell mass (ICM) of the blastocyst, can give rise to all cells of the adult body—derived from the three germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm)—but cannot form extraembryonic structures [13] [14].

In plants, the concepts of totipotency and pluripotency are equally pivotal, underpinning their remarkable regenerative capabilities. Theoretically, every somatic plant cell is totipotent, retaining the ability to regenerate a complete new plant [15]. This totipotency is the cytological foundation for plant regeneration, which is exploited extensively in agricultural techniques such as cutting propagation and advanced biotechnology like tissue culture and genetic transformation [1]. Pluripotent cells in plants are found in meristematic tissues (e.g., shoot apical meristem, root apical meristem), which are responsible for generating specific lineages of organs and tissues [1] [15].

Understanding the distinctions between these potent states is not merely an academic exercise; it is crucial for advancing regenerative medicine and improving plant genetic transformation methodologies. This review objectively compares the developmental potential, molecular signatures, and experimental applications of totipotent and pluripotent cells, with a specific focus on their role as the biological basis for regeneration.

Table 1: Core Definitions and Key Characteristics of Potency States

| Feature | Totipotency | Pluripotency |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Ability to form a complete organism plus extraembryonic tissues [11] | Ability to form all cells of the three germ layers, but not extraembryonic tissues [11] |

| Natural Occurrence (Mammals) | Zygote, early blastomeres (e.g., 2- to 4-cell stage) [12] | Inner cell mass (ICM) of the blastocyst [13] |

| Natural Occurrence (Plants) | Somatic cells under specific induction [15] | Cells in shoot/root apical meristems [1] |

| Key In Vitro Models (Mammals) | Totipotent-like cells (e.g., 2-cell-like cells in mouse) [16] | Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs), Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) [11] [14] |

| Key In Vitro Models (Plants) | Embryogenic callus in somatic embryogenesis [15] | Pluripotent callus in de novo organogenesis [15] |

Molecular Hallmarks and Functional Assays

The distinct developmental capacities of totipotent and pluripotent cells are governed by unique molecular landscapes. A core network of transcription factors, including OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG, is essential for maintaining pluripotency [13] [12]. These factors regulate a suite of genes that keep the cell in an undifferentiated state, poised for lineage specification. Totipotent cells, by contrast, exhibit a more open chromatin state and express a distinct set of genes, such as Zscan4 and Eomes, which are associated with their expanded developmental potential [11]. The transition from totipotency to pluripotency involves significant epigenetic reprogramming, including DNA demethylation and specific histone modifications, which progressively restrict cell fate [11] [13].

Functionally, these states are validated through rigorous in vivo and in vitro assays. The gold-standard functional test for totipotency is the ability of a single cell to generate a complete, fertile organism, including all extraembryonic tissues, as demonstrated by tetraploid complementation in mice [13]. For pluripotent cells, key assays include teratoma formation—where injected cells form tumors containing tissues from all three germ layers—and chimera formation, where the cells contribute to various tissues in a developing host embryo [11] [13].

Figure 1: Developmental Trajectory from a Totipotent Zygote. The totipotent zygote gives rise to all embryonic (via the pluripotent ICM) and extraembryonic tissues (via the trophectoderm).

Comparative Efficiency in Plant Genetic Transformation

In plant biotechnology, the principles of totipotency and pluripotency are directly harnessed for genetic transformation. The efficiency of these processes is heavily dependent on the plant's regenerative capacity, which is often the primary bottleneck [1] [17]. Transformation strategies can be broadly categorized into those relying on somatic embryogenesis (involving a totipotent state) and de novo organogenesis (involving a pluripotent state) [15].

- Somatic Embryogenesis: This process involves reprogramming a somatic cell to become a totipotent embryogenic callus cell, which can then develop into a somatic embryo and a whole plant. It can be direct or, more commonly, indirect via a callus phase [15]. This pathway is central to many transformation protocols for major crops like maize and rice.

- De novo Organogenesis: This pathway involves the formation of adventitious roots or shoots directly from an explant or indirectly through a pluripotent callus. This callus is not embryogenic but can be induced to form organ primordia. It reflects the pluripotency of certain cell types and is widely used in plant tissue culture [15].

The efficiency of these regeneration pathways is quantitatively measured by key metrics, as summarized in Table 2. The choice of pathway and explant has a direct impact on transformation success, timeframes, and the risk of undesirable genetic variations.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Plant Regeneration Pathways for Genetic Transformation

| Regeneration Pathway | Cellular Basis | Typical Explants | Transformation Efficiency Range | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Somatic Embryogenesis | Totipotency [15] | Immature embryos, shoot tips [15] | Highly variable; e.g., 2.7% to 45.3% in wheat [17] | High multiplication rate; produces many plantlets [15] | Long duration; high somaclonal variation risk [15] |

| De novo Organogenesis | Pluripotency [15] | Leaves, roots, floral tissues [15] | High in model plants (e.g., Arabidopsis, tomato); low in cereals [17] | Direct regeneration avoids callus phase; lower somaclonal variation [15] | Fewer regenerated plantlets; strong genotype dependence [17] [15] |

Experimental Protocols and Enhancement Strategies

Protocol for Agrobacterium-Mediated Transformation via Somatic Embryogenesis

This is a standard protocol for generating transgenic plants in cereals like maize, relying on indirect somatic embryogenesis [15] [18].

- Explant Preparation: Sterilize immature embryos (1.0-2.0 mm in size) harvested from plants.

- Callus Induction (Dedifferentiation): Culture embryos on a Callus-Inducing Medium (CIM). This medium is rich in auxin (e.g., 2,4-D) and has low cytokinin, promoting the formation of a totipotent, embryogenic callus. Incubate in the dark for 2-4 weeks.

- Agrobacterium Co-cultivation: Harvest the embryogenic callus and immerse in a suspension of Agrobacterium tumefaciens carrying the gene of interest. Co-cultivate for a short period to allow T-DNA transfer.

- Selection and Regeneration (Differentiation): Transfer the callus to a fresh CIM containing antibiotics to eliminate Agrobacterium and select for transformed cells (using a selectable marker like an antibiotic/herbicide resistance gene). After selection, transfer the transgenic callus to a Shoot-Inducing Medium (SIM), which has high cytokinin and low auxin, to promote shoot formation.

- Rooting and Acclimatization: Excise developed shoots and transfer to a Root-Inducing Medium (RIM) containing auxin to encourage root development. Finally, transfer the plantlets to soil for acclimatization.

Enhancing Efficiency with Developmental Regulators

A major advancement in overcoming genotype-dependent regeneration is the use of developmental regulators (DRs). These are transcription factors that can enhance or induce the formation of totipotent or pluripotent cells [17] [18]. Their application can dramatically improve transformation efficiency, as shown by experimental data.

Table 3: Quantitative Impact of Key Developmental Regulators on Transformation Efficiency

| Developmental Regulator | Target Species | Function | Experimental Impact on Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| TaWOX5 [17] | Wheat (Triticum aestivum) | Promotes pluripotency acquisition in callus; shoot regeneration. | Increased transformation efficiency in recalcitrant variety 'Jimai22' from 5.8% to 55.4% [17]. |

| ZmBBM & ZmWUS2 [17] | Maize (Zea mays) | Activates cell proliferation and somatic embryogenesis. | Combination enhanced transformation in monocots; enabled direct transformation of mature seed-derived tissues, bypassing callus culture [17]. |

| GRF4-GIF1 [18] | Wheat (Triticum aestivum) | Promotes cell proliferation and shoot regeneration. | Increased regeneration frequency in hexaploid wheat from 12.7% to 61.8% [18]. |

| REF1 [18] | Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) | Wound-signaling molecule promoting callus and bud regeneration. | Increased regeneration efficiency by 5- to 19-fold and transformation efficiency by 6- to 12-fold in wild tomato [18]. |

Figure 2: Workflow for Enhanced Plant Genetic Transformation. Key steps show how developmental regulators (DRs) enhance the formation of totipotent callus.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Leveraging totipotency and pluripotency in research requires a specific set of reagents and tools. The following table details essential materials used in this field.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Studying and Applying Totipotency/Pluripotency

| Research Reagent / Tool | Category | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Yamanaka Factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC) [11] | Reprogramming Factors | Reprogram somatic cells into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [11]. |

| 2i/LIF Culture System [13] | Cell Culture Medium | Maintains mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) in a naive pluripotent state by inhibiting differentiation signals [13]. |

| Morphogenic Regulators (BBM, WUS, WOX) [17] [18] | Developmental Regulators | Enhances plant transformation efficiency by promoting callus formation and shoot regeneration in recalcitrant species [17]. |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens Strain (e.g., EHA105, GV3101) [1] [19] | Transformation Vector | Delivers foreign DNA (T-DNA) into plant cells for stable genetic transformation [1]. |

| Callus-Inducing Medium (CIM) [15] | Plant Tissue Culture Medium | Induces dedifferentiation of somatic plant cells to form totipotent callus, typically with high auxin (2,4-D) [15]. |

| Anti-OCT4 / Anti-SOX2 / Anti-NANOG Antibodies [12] | Molecular Biology Reagents | Detects and validates the presence of core pluripotency factors via immunostaining or Western blot. |

The objective comparison between totipotent and pluripotent states reveals a clear hierarchy of developmental potential, each with distinct molecular signatures and functional applications. In mammalian systems, pluripotent stem cells like ESCs and iPSCs are currently more therapeutically accessible, while research into totipotent-like cells deepens our understanding of early development. In plant science, both states are directly exploited, with somatic embryogenesis (totipotency) and de novo organogenesis (pluripotency) serving as the two pillars of in vitro regeneration and genetic transformation.

The efficiency of these processes, particularly in plants, is no longer solely dependent on innate genotype. The strategic application of developmental regulators is demonstrably overcoming traditional bottlenecks, as evidenced by the quantitative data on factors like TaWOX5 and BBM/WUS. This progress underscores that the future of regenerative biology and crop engineering lies in the precise manipulation of the very molecular pathways that govern cellular totipotency and pluripotency.

Plant genetic transformation is a foundational technique in modern plant biotechnology, enabling the introduction of foreign genes into a plant's genome to confer new traits such as disease resistance, improved nutritional content, or environmental resilience [1]. These methods are broadly categorized into two distinct groups: direct gene transfer methods and bio-mediated transformation methods [1]. Direct gene transfer techniques, such as microprojectile bombardment and protoplast methods, involve the physical or chemical delivery of DNA directly into plant cells without a biological vector. In contrast, bio-mediated transformation primarily utilizes biological agents like Agrobacterium tumefaciens or viruses to facilitate gene transfer [1]. The choice between these approaches depends on multiple factors, including the plant species, the intended application, and the available resources, with each category offering distinct advantages and limitations in terms of efficiency, cost, and technical complexity [20].

Direct Gene Transfer Methods

Core Principles and Techniques

Direct gene transfer methods are characterized by the physical or chemical delivery of foreign DNA directly into plant cells, bypassing biological vectors. A key advantage of these methods is their ability to transform a wide range of species and tissue types, making them particularly valuable for plants recalcitrant to Agrobacterium-mediated transformation [21] [20].

- Microprojectile Bombardment (Biolistics): This technique involves coating microscopic particles of gold or tungsten with DNA and propelling them into plant cells or tissues using high-pressure helium or gunpowder [21] [20]. The process can deliver various biological cargoes, including DNA, RNA, and proteins (such as CRISPR-Cas ribonucleoproteins), independent of tissue type or plant genotype [21]. A recent innovation, the Flow Guiding Barrel (FGB), has been developed to address traditional biolistic inefficiencies. This device optimizes gas and particle flow, achieving a 22-fold enhancement in transient transfection efficiency and significantly improving stable transformation frequency in maize [21].

- Protoplast-Mediated Transformation: This method involves the enzymatic removal of plant cell walls to create naked protoplasts, followed by the introduction of DNA using polyethylene glycol (PEG) or electroporation to facilitate membrane permeability [20]. While this system is highly efficient for transient gene expression studies, the regeneration of fertile plants from protoplasts remains technically challenging and species-dependent [1].

- Other Direct Methods: Additional techniques include liposome-mediated transfer, electroshock conversion, and the pollen tube pathway [1]. The pollen tube pathway, for instance, involves injecting exogenous DNA into the ovary after pollination; the pollen tube then acts as a conduit for the DNA to enter the fertilized egg, achieving transformation efficiencies of up to 2.54% in certain species like Paphiopedilum Maudiae [1].

Experimental Protocol: Microprojectile Bombardment

The following workflow details the key steps for stable plant transformation via microprojectile bombardment, optimized using the Flow Guiding Barrel (FGB) device [21].

- Microcarrier Preparation: Suspend 1µg of gold particles (0.6 µm diameter) in 10µL of sterile water. Add 1µg of plasmid DNA (e.g., pLMNC95 for GFP expression), 10µL of 2.5M CaCl₂, and 4µL of 0.1M spermidine. Vortex continuously for 3-5 minutes to coat the particles with DNA.

- Precipitation and Washing: Centrifuge the mixture briefly, remove the supernatant, and wash the DNA-gold pellets three times with 100% ethanol. Resuspend the final pellet in 20µL of 100% ethanol.

- Target Tissue Preparation: For maize transformation, isolate 100 immature embryos (1.0-1.5 mm in size) from the B104 inbred line and place them scutellum-side up on a bombardment plate containing osmotic adjustment medium.

- Bombardment Parameters: Use a PDS-1000/He system equipped with the FGB device. Set the helium pressure to 650 psi and the target distance to 6 cm. Execute a single bombardment per plate.

- Post-Bombardment Culture and Selection: Transfer bombarded embryos to callus induction medium. After a 7-day resting period, transfer the embryos to a selection medium containing herbicides or antibiotics to identify stably transformed events. Transgenic plantlets can be regenerated within 10-12 weeks.

Research Reagent Solutions for Direct Gene Transfer

The following table lists essential reagents and their specific functions in direct gene transfer protocols.

| Research Reagent | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Gold microparticles (0.6 µm) | Microcarriers for DNA delivery into cells [21] |

| Spermidine | Binds DNA to microcarrier particles [21] |

| CaCl₂ (Calcium Chloride) | Co-precipitant for DNA adhesion to microcarriers [21] |

| Plasmid DNA (e.g., pLMNC95) | Vector carrying gene of interest and selectable marker [21] |

| Acetosyringone | Phenolic compound that can enhance DNA delivery in some direct methods |

Bio-mediated Transformation Methods

Core Principles and Techniques

Bio-mediated transformation harnesses the natural genetic engineering capabilities of biological vectors, primarily Agrobacterium tumefaciens, to transfer and integrate foreign DNA into the plant genome [1] [20].

- Agrobacterium tumefaciens-Mediated Transformation: This method utilizes a disarmed soil bacterium that naturally transfers a segment of its tumor-inducing (Ti) plasmid, known as T-DNA, into the plant genome [20] [22]. The process begins with the bacterium sensing plant wound signals, such as acetosyringone, which activates its virulence (vir) genes [23] [22]. The T-DNA, which can be engineered to carry genes of interest, is then excised, transported, and integrated into the plant's nuclear DNA [20]. This method is popular due to its relatively low cost, ability to transfer large DNA fragments, and tendency to produce transgenic plants with low-copy-number, clean integration events [20] [22]. Its success has been extended from dicots to many monocots, including major cereals [20].

- Virus-Mediated Transformation: While less commonly used for stable transformation, plant viruses can be engineered as vectors for transient gene expression and functional studies, though they are not a primary focus of this comparison guide [1].

- Agrobacterium rhizogenes-Mediated Transformation (Hairy Root System): This variation uses a related bacterium that transfers root-inducing (Ri) plasmid DNA, leading to the development of transgenic "hairy roots" [23] [24]. This system is highly valuable for functional genomics studies, particularly for investigating root biology and producing secondary metabolites. A recent study in Liriodendron hybrid demonstrated its efficacy, achieving transformation efficiencies of 15.51% to 60.63% across different genotypes using the K599 strain [24].

Experimental Protocol: Agrobacterium-Mediated Transformation

This protocol outlines the highly efficient transformation of photosynthetic Arabidopsis suspension cells, achieving nearly 100% transient infection rates [22].

- Agrobacterium Preparation: Inoculate the hypervirulent A. tumefaciens strain AGL1 (harboring the binary vector with the gene of interest, e.g., GFP) from a glycerol stock into YEB medium with appropriate antibiotics. Grow the main culture in AB-MES medium supplemented with 200 µM acetosyringone at 28°C until OD₆₀₀ reaches 0.3-0.5. Harvest bacterial cells by centrifugation and resuspend in ABM-MS medium to an OD₆₀₀ of 0.8 [22].

- Plant Material Preparation: Subculture photosynthetically active green Arabidopsis suspension cells in MS1 medium for 4-5 days to reach the mid-exponential growth phase [22].

- Co-cultivation: Wash the plant suspension cells twice with ABM-MS medium and adjust the packed cell volume to 70%. Mix the washed plant cells with the prepared Agrobacterium suspension and 200 µM acetosyringone. Plate the mixture onto solid ABM-MS medium containing 8 g/L plant agar and 0.05% (w/v) Pluronic F68. After drying, seal the plates and incubate at 24°C under continuous light for 2 days [22].

- Elimination of Agrobacterium and Regeneration: Following co-cultivation, wash the plant cells thoroughly with ABM-MS medium containing 250 µg/mL ticarcillin to eliminate residual Agrobacterium. For stable transformation, transfer the cells to a regeneration medium with a selection agent (e.g., kanamycin) to select for transformed events [22].

Research Reagent Solutions for Bio-mediated Transformation

The following table lists essential reagents and their specific functions in bio-mediated transformation protocols.

| Research Reagent | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Agrobacterium Strain (e.g., AGL1, EHA105) | Engineered bacterial vector for T-DNA delivery [22] [24] |

| Acetosyringone | Phenolic compound that induces Agrobacterium vir gene expression [22] |

| Binary Vector (e.g., pRI101, pCAMBIA) | Plasmid carrying gene of interest between T-DNA borders [24] |

| Pluronic F68 | Surfactant that enhances transformation efficiency [22] |

| Antibiotics (e.g., Kanamycin, Ticarcillin) | Selection for transformed plants and elimination of Agrobacterium [22] |

Comparative Analysis of Transformation Methods

The following table provides a structured comparison of the key performance metrics and characteristics of direct and bio-mediated transformation methods, synthesizing data from recent studies.

| Feature | Direct Gene Transfer (Biolistics) | Bio-mediated (Agrobacterium) |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | Physical/chemical force delivers DNA [20] | Biological T-DNA transfer from bacterium [20] |

| Primary Technique | Microprojectile Bombardment [21] | A. tumefaciens-mediated transfer [1] |

| Host Range | Very broad; genotype-independent [21] | Broad, but efficiency varies by species [20] |

| Cargo Type | DNA, RNA, Proteins (e.g., CRISPR RNP) [21] | Primarily DNA (plasmids, T-DNA) [20] |

| Typical Integration | Complex, multi-copy insertions possible [21] [23] | Cleaner, low-copy-number, defined ends [20] |

| Transformation Efficiency (Example) | 10-fold increase in stable maize transformation with FGB [21] | Up to ~100% transient rate in optimized suspension cells [22] |

| Transgene Structure | Can be fragmented or rearranged [21] | Fewer rearrangements [20] |

| Relative Cost & Skill | High (specialized equipment) [23] | Low (minimal specialized equipment) [20] |

| Key Advantage | Delivers diverse cargo to recalcitrant species [21] | High-quality integration, low cost [20] [22] |

| Key Limitation | Complex transgene integration patterns [23] | Genotype-dependent efficiency, host range limits [1] |

Workflow Diagrams of Core Methodologies

Agrobacterium-Mediated Transformation Workflow

Biolistic Transformation Workflow

The strategic selection between direct and bio-mediated transformation methods is paramount for the success of plant genetic engineering projects. As the comparative data illustrates, bio-mediated methods, particularly Agrobacterium-mediated transformation, often provide superior integration quality and are more cost-effective for a wide range of dicot and monocot species [20] [22]. Conversely, direct methods like microprojectile bombardment offer an indispensable solution for genotype-independent transformation and the delivery of non-DNA cargo, such as CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoproteins for DNA-free genome editing [21].

The ongoing innovation in both categories, such as the development of the Flow Guiding Barrel for biolistics [21] and hypervirulent Agrobacterium strains for high-efficiency transformation [22], continues to push the boundaries of plant biotechnology. The choice of method ultimately hinges on the specific requirements of the experiment, including the target plant species, the desired transgene structure, the type of cargo, and the available laboratory resources. A comprehensive understanding of the principles, protocols, and comparative performance of these major transformation categories provides researchers with the foundational knowledge necessary to design and execute effective genetic transformation strategies.

The Critical Link Between Regeneration Capacity and Transformation Success

Regeneration capacity—the ability of plant cells to form new tissues or organs—is a fundamental biological process and the cornerstone of successful plant genetic transformation. This capability enables plants to repair themselves after damage and serves as the cytological foundation for in vitro plant regeneration systems used in genetic engineering [1]. For researchers aiming to develop genetically modified crops, the regeneration potential of explants often represents the primary bottleneck in the transformation pipeline [1] [25].

The efficiency of plant genetic transformation is highly dependent on species, genotypes, and explant types [25] [26]. While model plants like Arabidopsis and tomato consistently achieve high transformation efficiency, essential cereals such as maize and wheat show significantly lower efficiency and often require labor-intensive methods using immature embryos as explants [25]. This review examines the critical relationship between regeneration capacity and transformation success, comparing performance across species and methods while providing experimental data and protocols to guide researcher decision-making.

The Regeneration-Transformation Nexus: Key Mechanisms

Plant regeneration in vitro typically follows a biphasic process: (1) acquisition of cell pluripotency on auxin-enriched callus-inducing medium (CIM), and (2) de novo shoot or root regeneration on cytokinin-enriched shoot-inducing medium (SIM) [27]. Successful transformation depends on optimizing both phases, which are regulated by complex interactions between phytohormones, transcription factors, and signaling pathways [27] [25].

Molecular Regulators of Regeneration Capacity

Several key molecular pathways have been identified as critical regulators of plant regeneration capacity:

1. WOX Transcription Factors WUSCHEL-related homeobox (WOX) transcription factors control stem cell fate in meristems [25]. WOX5 is a key regulator of pluripotency acquisition in callus formation [25]. In wheat, TaWOX5 expression dramatically improved transformation efficiency, achieving up to 94.5% in readily transformable varieties and increasing efficiency from 5.8% to 55.4% in the recalcitrant variety Jimai22 [25].

2. BBM-WUS Morphogenic Factors The BABY BOOM (BBM) and WUSCHEL (WUS) transcription factors activate cell proliferation and morphogenesis during somatic embryogenesis [25]. In maize, ZmBBM expression increases callus transformation efficiency, while ZmWUS2 stimulates somatic embryo formation [25]. Their combination further enhances transformation efficiency, enabling direct Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of mature seed-derived embryo axes while eliminating dependence on immature embryo quality [25].

3. Small Signaling Peptides Recent research has identified small signaling peptides as novel regulators of regeneration capacity [27]. CLAVATA3/EMBRYO SURROUNDING REGION-RELATED (CLE) peptides negatively regulate shoot regeneration through CLAVATA1 (CLV1) and BARELY ANY MERISTEM1 (BAM1) receptors [27]. Conversely, REGENERATION FACTOR1 (REF1) peptide promotes regeneration by binding to PEPR1/2 ORTHOLOG RECEPTOR-LIKE KINASE 1 (PORK1) and activating WOUND-INDUCED DEDIFFERENTIATION 1 (WIND1) expression [27].

The following diagram illustrates the core regulatory pathways governing plant regeneration capacity:

Comparative Analysis of Regeneration and Transformation Efficiency

Genotype-Dependent Regeneration Capacity

Substantial evidence indicates that regeneration capacity and transformation efficiency vary significantly across species and genotypes, with many elite varieties being particularly recalcitrant to genetic transformation [25]. The following table summarizes comparative regeneration and transformation efficiencies across diverse plant species:

Table 1: Comparative Regeneration and Transformation Efficiencies Across Plant Species

| Species/Genotype | Explant Type | Regeneration Efficiency | Transformation Efficiency | Key Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat (Triticum aestivum) | ||||

| Fielder (model) | Immature embryos | High | Up to 45.3% [25] | Genotype, explant quality |

| Jimai22 (elite) | Immature embryos | Low | 2.7-5.8% [25] | High recalcitrance |

| Jimai22 + TaWOX5 | Immature embryos | Enhanced | 55.4% [25] | Morphogenic factor |

| Soybean (Glycine max) | ||||

| Model genotypes | Various | High | Transformable [25] | Genotype flexibility |

| Elite varieties | Various | Low | Rarely successful [25] | High recalcitrance |

| Grapevine (Vitis spp.) | ||||

| Thompson Seedless | Meristematic bulk | ~100% [26] | High [26] | High competence |

| Kober 5BB | Meristematic bulk | ~100% [26] | Callus only [26] | Limited regeneration |

| 110 Richter | Meristematic bulk | Lower shoots/explant [26] | Callus only [26] | Limited regeneration |

| Oil Palm (Elaeis guineensis) | Embryogenic calli | Variable | 0.7-1.5% [28] | Monocot recalcitrance |

Transformation Method Efficiency Comparison

Different genetic transformation methods yield varying efficiencies based on plant species and regeneration capacity:

Table 2: Transformation Method Efficiency Comparison

| Transformation Method | Key Features | Ideal For | Limitations | Reported Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agrobacterium-mediated | Biological vector, T-DNA integration, relatively simple [1] | Dicots, some monocots, model species [1] [28] | Host range limitations, genotype dependence [1] | Varies widely: 0.7-94.5% based on species and genotype [25] [28] |

| Pollen-tube Pathway | In planta transformation, avoids tissue culture [1] | Species with accessible pollen tubes (cotton, melon) [1] | Limited to specific developmental stages, low efficiency [1] | ~2.54% (Paphiopedilum) [1] |

| Ternary Vector Systems | Additional virulence genes, immune suppressors [29] | Recalcitrant crops (maize, sorghum, soybean) [29] | More complex vector design | 1.5-21.5× improvement over standard methods [29] |

| Morphogenic Factor-enhanced | BBM, WUS, WOX genes promote regeneration [25] | Recalcitrant genotypes, elite varieties [25] | Potential pleiotropic effects, requires transgene excision [25] | Up to 94.5% in wheat with TaWOX5 [25] |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Regeneration-Transformation Competence

Standardized Agrobacterium-Mediated Transformation Protocol

The following detailed methodology has been successfully applied for tomato and grapevine transformation, with modifications possible for other species:

1. Explant Preparation and Meristematic Bulk Induction

- Source Material: Collect shoot tips from sterile in vitro-grown plants [26].

- Culture Conditions: Place explants on media containing increasing concentrations of cytokinins to induce meristematic bulk (MB) formation [26].

- Duration: 3-9 weeks with regular subculturing to maintain meristematic state [26].

2. Agrobacterium Preparation and Inoculation

- Strain Selection: EHA105 is commonly employed for grapevine transformations [26]. Other strains (e.g., LBA4404) may be species-dependent.

- Vector System: Binary vectors (e.g., pK7WG2) carrying selectable markers (nptII for kanamycin resistance) and reporter genes (eGFP) [26].

- Inoculation: Prepare Agrobacterium suspension to OD₆₀₀ of 0.5-1.0 in liquid medium [30]. Immerse MB slices for 15-30 minutes [26].

3. Co-cultivation and Selection

- Co-cultivation Period: 2-3 days on appropriate medium in dark conditions [30] [26].

- Selection Medium: Transfer explants to shoot induction medium containing appropriate antibiotics (e.g., 70 mg/L kanamycin for grapevine) [26] and bacteriostat (e.g., cefotaxime) to eliminate Agrobacterium [30].

- Visual Screening: Enhanced GFP fluorescence can be used alone or combined with antibiotic selection for identifying transformed tissues [26].

4. Regeneration and Plant Recovery

- Shoot Induction: Maintain selected tissues on shoot induction medium with regular subculturing every 2-3 weeks [30].

- Rooting: Transfer developed shoots to rooting medium, typically containing auxins like IAA or NAA [30].

- Acclimatization: Transfer rooted plantlets to soil under high-humidity conditions before moving to standard growth environments [30].

The experimental workflow for assessing regeneration and transformation competence is illustrated below:

Enhancement Strategies for Recalcitrant Genotypes

For genotypes with inherently low regeneration capacity, several enhancement strategies have proven effective:

1. Morphogenic Gene Overexpression

- Introduce genes such as TaWOX5, BBM, or WUS under regulated promoters [25].

- Use tissue-specific or inducible promoters to avoid pleiotropic effects [25].

- Implement "altruistic" transformation systems where morphogenic genes are transiently expressed in neighboring cells to stimulate somatic embryogenesis [25].

2. Small Signaling Peptide Application

- Apply synthetic REF1 peptide to enhance callus formation and shoot regeneration in tomato, soybean, wheat, and maize [27].

- Optimize concentration for dose-responsive enhancement (typically 0.1-10 μM) [27].

3. Ternary Vector Systems

- Employ advanced vector systems with accessory virulence genes and immune suppressors [29].

- These systems overcome intrinsic transformation barriers in recalcitrant crops [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Regeneration and Transformation Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agrobacterium Strains | EHA105, LBA4404, GV3101 [30] [26] | T-DNA delivery, host range specificity | Strain selection affects transformation efficiency; EHA105 shows broad efficacy [26] |

| Vector Systems | Binary vectors (pK7WG2), Ternary vectors [26] [29] | Gene delivery, selection, expression | Ternary vectors with virulence genes enhance efficiency in recalcitrant species [29] |

| Selection Agents | Kanamycin (50-100 mg/L), Hygromycin [26] | Selective pressure for transformed tissues | Concentration must be optimized per species/genotype to minimize escapes [26] |

| Visual Reporters | eGFP, GUS [26] | Non-destructive screening of transformed tissues | Enables early identification, reduces antibiotic dependence [26] |

| Morphogenic Regulators | TaWOX5, BBM, WUS, GRF-GIF [25] | Enhance regeneration competence, overcome genotype limitations | May cause pleiotropic effects; use inducible systems recommended [25] |

| Signaling Peptides | REF1, CLE peptides, RALF33 [27] | Modulate regeneration pathways, enhance transformation | Dose-responsive effects; REF1 shows cross-species efficacy [27] |

| Hormone Stocks | Auxins (2,4-D, IAA), Cytokinins (BAP, TDZ) [27] [25] | Regulate callus formation and shoot regeneration | Balance and timing critical for phase transition in regeneration [27] |

Regeneration capacity stands as the critical determinant of plant genetic transformation success. The comparative data presented demonstrates substantial variability in both regeneration competence and transformation efficiency across species and genotypes. While technical aspects of gene transfer have advanced significantly, the fundamental biological constraint remains the innate ability of plant cells to regenerate into whole organisms.

Emerging strategies focusing on morphogenic regulators and signaling pathways offer promising avenues for overcoming regeneration limitations. The targeted manipulation of WOX transcription factors, BBM-WUS combinations, and small signaling peptides like REF1 has already demonstrated remarkable success in enhancing transformation efficiency, particularly in recalcitrant species and elite cultivars.

For researchers pursuing plant genetic engineering, particularly with applications in crop improvement, prioritizing regeneration capacity assessment in early experimental design is essential. The protocols and reagents detailed in this review provide a foundation for systematically evaluating and enhancing this critical trait, ultimately enabling more efficient genetic modification across diverse plant species.

A fundamental challenge constrains advances in plant biology and crop improvement: many elite crop varieties are recalcitrant to genetic transformation [25] [1]. This genotype dependency creates a significant bottleneck, as the most commercially valuable cultivars often prove the most difficult to modify genetically, while transformation protocols work efficiently only in a few, often non-elite, "model" genotypes [25] [31]. For instance, in wheat, transformation efficiency can range from a mere 2.7% in the commercial variety Jimai22 to 45.3% in the model genotype Fielder, with some agriculturally important varieties like Aikang58 and Jing411 failing to produce transgenic plants entirely [25] [17]. Similarly, in soybean, model genotypes are readily transformed, whereas elite commercial varieties such as Heihe43 and Zhonghuang13 are rarely transformed successfully [25]. This article examines the comparative efficiency of different approaches to overcoming this recalcitrance, focusing on experimental data and underlying molecular mechanisms.

Quantitative Comparison of Transformation Efficiency Across Methods and Genotypes

The extent of genotype dependency is starkly visible in comparative transformation studies. The following table summarizes documented transformation efficiencies for various crops, highlighting the disparity between model and elite varieties.

Table 1: Documented Transformation Efficiencies in Different Plant Species and Genotypes

| Plant Species | Genotype/Variety | Transformation Method | Reported Efficiency | Key Factor Influencing Efficiency | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat (Triticum aestivum) | Fielder (Model) | Agrobacterium-mediated | 45.3% | Baseline genotype susceptibility | [25] |

| Jimai22 (Elite) | Agrobacterium-mediated | 2.7% - 5.8% | Baseline genotype recalcitrance | [25] | |

| Jimai22 (Elite) | Agrobacterium-mediated + TaWOX5 | 55.4% | Morphogenic factor (WOX) | [25] [17] | |

| Multiple Elites (Baj, Kachu, etc.) | Particle Bombardment + GRF4-GIF1 | 5% - 13% | Morphogenic factor (GRF-GIF) | [32] | |

| Barley (Hordeum vulgare) | GanPi 6 & L07 (Compatible) | Agrobacterium-mediated (MDEC) | 53.2% - 56.2% | Compatible genotype | [33] |

| Hong 99 (Recalcitrant) | Agrobacterium-mediated (MDEC) | 5.4% | Recalcitrant genotype | [33] | |

| Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) | Various | Agrobacterium-mediated | 0.5% - 28.6% | Protocol optimization (e.g., sonication, vacuum, hormones) | [31] |

| Maize (Zea mays) | Recalcitrant Genotypes | Agrobacterium-mediated + BBM-WUS | Significant increase reported | Morphogenic factor (BBM-WUS) | [25] [17] |

The data demonstrates that leveraging developmental regulators like WOX, BBM-WUS, and GRF-GIF can dramatically enhance efficiency in otherwise recalcitrant backgrounds, in some cases raising it to levels comparable with model genotypes [25] [32] [17].

Molecular Mechanisms of Recalcitrance and Susceptibility

The genotype-dependent response to transformation is governed by complex molecular pathways. Research has identified several key mechanisms.

The Role of Developmental (Morphogenic) Factors

A primary pathway to recalcitrance is the inability of explant cells to dedifferentiate and regenerate. Key morphogenic transcription factors that masterfully regulate this process have been identified and utilized to overcome this barrier [25] [17].

- WOX Transcription Factors: WUSCHEL-related homeobox (WOX) proteins are crucial for establishing cellular pluripotency. In wheat, overexpression of TaWOX5 increased transformation efficiency in the recalcitrant variety Jimai22 from 5.8% to 55.4% [25] [17]. It is believed that WOX factors modulate auxin and cytokinin responsiveness, which are critical for callus formation and shoot regeneration [25].

- BBM and WUS: The combination of the transcription factors BABY BOOM (BBM) and WUSCHEL (WUS) has been highly effective in monocots. In maize, their co-expression stimulates somatic embryogenesis, enhancing transformation efficiency and even enabling the transformation of mature seed-derived tissues, bypassing the need for immature embryos [25] [17]. A key challenge is that constitutive expression can cause developmental abnormalities, leading to strategies like the "altruistic" transformation system where transient WUS2 expression in some cells stimulates embryogenesis in neighboring, transformed cells [25].

- GRF-GIF Complexes: GROWTH-REGULATING FACTORS (GRFs) interacting with GRF-INTERACTING FACTORS (GIFs) are potent promoters of cell proliferation. A fusion protein of TaGRF4-TaGIF1 was used to achieve a 60-fold increase in transformation frequency in elite bread wheat cultivars, enabling efficient genome editing in previously recalcitrant lines [32].

Diagram 1: Simplified signaling pathway of morphogenic factors in transformation

Innate Plant Defense and Susceptibility Pathways

Beyond regeneration capacity, a plant's innate cellular environment determines its susceptibility to Agrobacterium infection. Transcriptomic studies comparing compatible and recalcitrant barley genotypes during infection revealed significant expressional variation in genes involved in pyruvate metabolism, plant hormone signal transduction, and DNA replication [33]. Furthermore, specific genes have been identified that act as global regulators of susceptibility.

- The MTF1 Pathway: A key discovery identified the Myb Transcription Factor 1 (MTF1) in Arabidopsis as a suppressor of transformation susceptibility [34]. Agrobacterium-secreted cytokinins trigger a signaling cascade that represses MTF1, which in turn leads to the increased expression of AT14A, a protein that may facilitate bacterial attachment to the plant cell [34]. Mutants with suppressed MTF1 are hyper-susceptible to transformation, highlighting this pathway's central role in genotypic recalcitrance.

Diagram 2: The MTF1 susceptibility pathway in Agrobacterium transformation

Experimental Protocols for Overcoming Recalcitrance

Protocol 1: Exploiting Morphogenic Factors for Wheat Transformation

A study successfully edited genes in elite bread wheat cultivars by incorporating the GRF4-GIF1 chimera [32].

- Key Experimental Workflow:

- Plant Material: Immature embryos were harvested from elite wheat cultivars (Baj, Kachu, Morocco, etc.) and the model cultivar Fielder.

- Vector Design: A binary vector containing a TaGRF4-TaGIF1 fusion gene driven by a maize ubiquitin promoter was used.

- Transformation: Immature embryos were transformed with the vector using the particle bombardment method.

- Regeneration: Transformed calli were regenerated on standard media. The presence of the GRF4-GIF1 protein dramatically improved regeneration efficiency.

- Genome Editing: Simultaneously, constructs containing CRISPR-Cas9 and guide RNAs targeting genes for leaf rust (Lr67) and powdery mildew (TaMLO) resistance were co-delivered.

- Result: Transformation frequency increased nearly 60-fold with the GRF4-GIF1-containing vectors compared to the control, ranging from ~5% to 13% across elite cultivars. Gene editing efficiency was high, with all three homeologs of the target genes successfully knocked out [32].

Diagram 3: Experimental workflow for GRF-GIF enhanced wheat transformation

Protocol 2: In planta Transformation to Bypass Tissue Culture

In planta methods represent a fundamentally different approach, aiming to transform plants with no or minimal tissue culture steps, thereby avoiding the regeneration bottleneck altogether [19] [35].

- Key Experimental Workflows:

- Floral Dip: Whole plants, typically at an early flowering stage, are submerged in a solution containing Agrobacterium and a surfactant. The bacteria transform the developing female gametophytes, leading to transgenic seeds in the next generation [19]. This method is famously successful in Arabidopsis.

- Pollen Transformation: Gene-editing tools are delivered into pollen grains via methods like electroporation or Agrobacterium infiltration. The transformed pollen is then used for pollination to produce edited seeds [35].

- Meristem Transformation: The shoot apical meristem (SAM) of embryos, seedlings, or mature plants is targeted by Agrobacterium or particle bombardment. The transformed meristematic cells can give rise to whole edited plants or germ cells [19] [35].

- Result: These methods are often more genotype-independent and avoid somaclonal variation. While efficiency can be variable and optimization is required for new species, they offer a simpler, faster, and more accessible alternative to traditional methods, particularly promising for perennial and recalcitrant crops [19] [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

The following table catalogs essential reagents and materials identified in the search results as critical for tackling genotype recalcitrance.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Overcoming Transformation Recalcitrance

| Reagent / Material | Type | Primary Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| TaWOX5 Expression Vector | Morphogenic Gene Construct | Enhances cellular pluripotency and callus formation; reduces genotype dependency. | Increased wheat transformation in Jimai22 from 5.8% to 55.4% [25] [17]. |

| ZmBBM/ZmWUS2 Expression Vectors | Morphogenic Gene Construct | Promotes somatic embryogenesis; enables transformation of mature tissues. | Enhanced transformation in maize, sorghum, and wheat; used in "altruistic" systems [25]. |

| GRF4-GIF1 Fusion Protein Vector | Morphogenic Gene Construct | Boosts plant regeneration efficiency from transformed tissues. | Achieved 60-fold increase in transformation frequency in elite wheat [32]. |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens LBA4404 | Bacterial Strain | Standard workhorse for Agrobacterium-mediated gene delivery. | Used in compatibility studies with barley microspore-derived embryogenic calli [33]. |

| Microspore-Derived Embryogenic Calli (MDEC) | Plant Explant | Provides a uniform, synchronized, and transformable cell population. | Served as subject for comparative transcriptome analysis of genotypic response in barley [33]. |

| Cytokinin (e.g., Kinetin) | Plant Hormone | Suppresses MTF1 expression to increase plant susceptibility to Agrobacterium infection. | Potential additive to transformation protocols to broaden host range [34]. |

A Practical Guide to Transformation Techniques: From Classic to Cutting-Edge

Agrobacterium tumefaciens and related Agrobacterium species are soil-borne pathogens that have been harnessed as one of the most powerful tools in plant genetic engineering. Since the initial reports in the early 1980s using Agrobacterium to generate transgenic plants, scientists have progressively improved this "natural genetic engineer" for biotechnology purposes [36]. The unique ability of Agrobacterium to transfer DNA to plant cells has been utilized for efficient delivery of genes of interest into plant genomes, revolutionizing functional genomics studies and crop improvement programs [37]. Today, many agronomically and horticulturally important species are routinely transformed using this bacterium, with an increasing number of transgenic varieties generated by Agrobacterium-mediated as opposed to particle bombardment-mediated transformation [36].

The transformation process is highly complex and evolved, involving genetic determinants of both the bacterium and the host plant cell [36]. Originally, Agrobacterium was considered only capable of transforming dicotyledonous plants, as they are the natural hosts for the bacterium. However, this paradigm shifted in 1987 when researchers demonstrated that Agrobacterium T-DNA could be incorporated into the genome of asparagus, a monocotyledon plant [28]. This breakthrough opened possibilities for transforming economically important cereal crops, including rice, maize, wheat, and barley [36] [28]. The continuous refinement of Agrobacterium-mediated transformation protocols has solidified its position as a versatile tool for plant genetic engineering nearly half a century after its discovery [38].

Molecular Mechanisms of Transformation

Bacterial Components and T-DNA Transfer

The molecular basis of genetic transformation of plant cells by Agrobacterium involves the transfer and integration of a specific DNA region from the bacterium into the plant nuclear genome. This process is mediated by two key genetic elements: the Tumor-inducing (Ti) plasmid or rhizogenic (Ri) plasmid and bacterial chromosomal genes [36] [39]. Ti plasmids are large, ranging from 200 to 800 kbp in size, and contain several functionally critical regions [36].

The T-DNA (transferred DNA) region, approximately 10-30 kbp in native plasmids, is defined by 25-bp direct repeat border sequences that exhibit high homology [36]. These border sequences serve as recognition sites for the VirD1/VirD2 endonuclease complex that processes T-DNA from the Ti plasmid [36]. The right border generally demonstrates more importance in the transfer process due to polarity established by the covalent attachment of VirD2 protein and the direction of DNA transfer [36].

Alongside T-DNA, Ti plasmids carry virulence (vir) genes that encode proteins essential for T-DNA processing and transfer [39]. These vir genes are organized into operons (virA, virB, virC, virD, virE, virG, etc.) and function in concert to excise T-DNA from the plasmid and deliver it to plant cells [36] [39]. Additionally, chromosomal genes in Agrobacterium (chv genes) participate in bacterial attachment to plant cells [39]. The presence of wounded plant tissue triggers the activation of these virulence genes through sensing specific plant-derived molecules like phenolic compounds and sugars [40] [37].

Figure 1: Agrobacterium Transformation Mechanism Signaling Pathway

Genetic Engineering of Agrobacterium Systems

For plant transformation purposes, Agrobacterium strains and vector systems have been extensively engineered. Initial modifications involved "disarming" Ti plasmids by deleting the natural tumor-inducing T-DNA regions responsible for pathogenicity while retaining the vir genes essential for DNA transfer [37]. This resulted in disarmed strains such as GV3101 (pMP90) and LBA4404 [37].

The development of the T-DNA binary vector system significantly simplified cloning procedures [37]. This system separates the T-DNA containing the genes of interest from the vir genes, with each residing on separate compatible plasmids [39]. The binary vector contains the T-DNA with left and right borders, multiple cloning site for gene of interest, plant selectable marker, bacterial selection marker, and origins of replication for both Escherichia coli and Agrobacterium [39].

Recent advancements include ternary vector systems that incorporate an additional helper plasmid carrying extra copies of vir genes to enhance transformation efficiency [37]. Similarly, super-binary vectors containing additional vir genes on the T-DNA vector have been developed, particularly beneficial for monocot transformation [37]. Other improvements include the development of auxotrophic Agrobacterium strains, such as thymidine auxotrophic lines, which require thymidine supplementation and can be easily eliminated after co-cultivation, reducing overgrowth issues [37].

A groundbreaking recent study demonstrated that engineering binary vectors to increase their copy number in Agrobacterium through point mutations in the origin of replication significantly improves transformation efficiency [41]. This approach enhanced plant transformation by up to 100% and fungal transformation by up to 400%, addressing a key bottleneck in plant and fungal engineering [41].

Workflow and Methodologies

Standard Transformation Protocol

The Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation process follows a systematic workflow that can be divided into distinct stages, each with specific requirements and optimization points. The basic steps include [40]:

- Gene Isolation and Vector Construction: Isolating genes of interest and creating functional transgenic constructs with appropriate expression promoters, codon optimization if needed, and marker genes for tracking gene expression.

- Plasmid Introduction into Agrobacterium: Inserting the T-DNA containing plasmid into Agrobacterium using various transformation methods.

- Plant-Bacterium Co-cultivation: Mixing transformed Agrobacterium with plant cells or tissues to allow T-DNA transfer into plant chromosomes.

- Selection and Regeneration: Growing transformed cells on selection media and regenerating genetically modified plants.

- Validation and Testing: Confirming transgene integration and expression through molecular analyses and evaluating trait performance.

The preparation of Agrobacterium competent cells is a critical step that influences overall transformation efficiency. While electroporation provides the highest transformation efficiency, freeze-thaw methods offer a cost-effective alternative suitable for high-throughput applications [42] [39]. Recent protocol miniaturization enables transformation in 50μl reactions using just 200ng of DNA, with efficient heat shock performed in thermal cyclers instead of water baths [42]. Transformed cells can be plated on six-well plates, simplifying storage and handling while maintaining efficiency sufficient for routine experiments (approximately 8 × 10³ CFU/μg DNA) [42].

High-Throughput and Automated Workflows

Recent advances have focused on developing semi-automated workflows to enable high-throughput experimentation. Researchers have optimized pipelines for Agrobacterium transformation that can be adapted to robotic automation using open-source platforms like Opentrons OT-2 [42]. This system allows up to 96 transformations per batch, significantly increasing throughput capacity.

For plant transformation itself, simplified and miniaturized protocols using six-well plates have been developed for model species like Marchantia polymorpha, reducing hands-on work and costs while maintaining efficiency [42]. These improvements enable testing approximately 100 constructs per month using conventional plant tissue culture facilities, dramatically accelerating design-build-test-learn cycles for plant biotechnology [42].

A key innovation in high-throughput workflows involves enhancing selection efficiency. For example, adding sucrose to selection media significantly improves the production of propagules like gemmae in Marchantia, accelerating the generation of isogenic plants [42]. The total time from genetic construct to stable transgenic plant ready for analysis has been reduced to just four weeks with these optimized protocols [42].

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Plant Transformation

Applications Across Species

Transformation Efficiency in Various Crop Plants