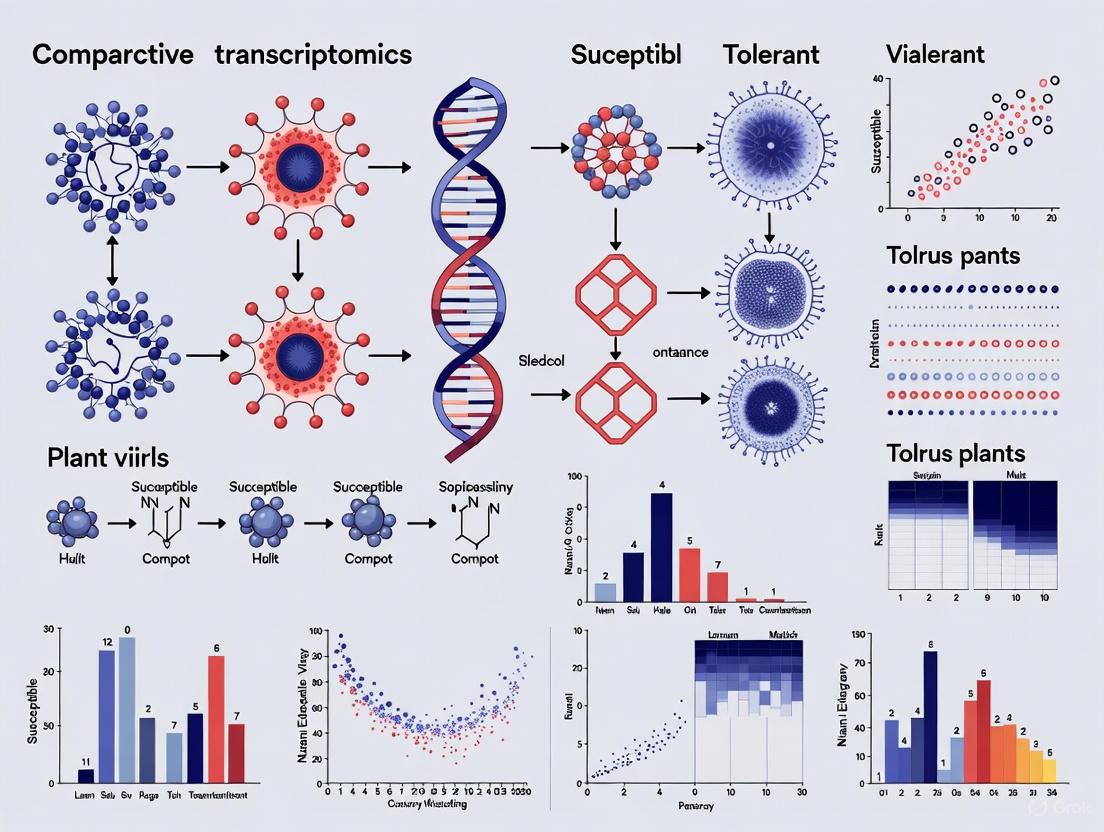

Comparative Transcriptomics of Susceptible and Tolerant Varieties: Uncovering Molecular Mechanisms for Stress-Resilient Crops

This article provides a comprehensive overview of comparative transcriptomics for investigating the molecular basis of stress tolerance in plants.

Comparative Transcriptomics of Susceptible and Tolerant Varieties: Uncovering Molecular Mechanisms for Stress-Resilient Crops

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of comparative transcriptomics for investigating the molecular basis of stress tolerance in plants. Aimed at researchers and scientists, it explores the foundational principles of identifying differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and key pathways in resistant versus susceptible varieties. The content covers essential methodologies from RNA-Seq to advanced network analyses like WGCNA, addresses common troubleshooting scenarios in cross-species and time-series studies, and validates findings through multi-species comparisons and meta-analyses. By synthesizing insights from recent studies on diseases, abiotic stresses, and developmental processes, this guide serves as a strategic resource for leveraging transcriptomic data to identify candidate genes and engineer improved crop varieties.

Core Principles and Discovery: Unraveling Differential Transcriptional Responses

Defining Comparative Transcriptomics and Its Power in Plant Stress Biology

Comparative transcriptomics represents a pivotal methodological framework in plant stress biology, enabling the systematic comparison of gene expression profiles across different biological conditions—such as stress-treated versus control plants, or tolerant versus susceptible varieties. By analyzing the complete set of RNA transcripts (the transcriptome) in a cell, tissue, or organism at a specific time, this approach uncovers the fundamental molecular mechanisms that govern plant responses to environmental challenges. This guide objectively compares the performance of various transcriptomic technologies and analytical pipelines, detailing their application in identifying critical stress-responsive pathways and candidate genes for breeding resilient crops. The content is framed within a broader thesis on comparative transcriptomics of susceptible and tolerant plant varieties, providing researchers and scientists with validated experimental protocols, data visualization tools, and essential reagent solutions to advance this field.

Comparative transcriptomics is founded on the principle that the expression of a plant's genome is dynamic and reflects its immediate functional state, including its response to stress [1]. The transcriptome encompasses all RNA molecules, including messenger RNA (mRNA) and non-coding RNA, transcribed from the DNA of a specific cell, tissue, or organ at a particular developmental stage or under specific environmental conditions [1]. Comparative transcriptomics extends this definition by analyzing differences in transcriptome profiles between contrasting groups—such as plants under stress versus control conditions, or tolerant cultivars versus susceptible ones. This comparison reveals differentially expressed genes (DEGs), which are statistically significant changes in gene expression levels associated with the condition being studied.

The power of this approach in plant stress biology lies in its ability to disclose the complex regulatory networks associated with a plant's adaptability and tolerance to stress at the whole-genome level [1]. Plant stress is generally categorized as either biotic stress (caused by living organisms like fungi, bacteria, viruses, and insects) or abiotic stress (resulting from physical or chemical conditions such as drought, salinity, extreme temperatures, and heavy metals) [1]. By applying comparative transcriptomics, researchers can move beyond studying individual genes to understanding system-wide molecular responses, thereby identifying key functional genes and regulatory pathways that can be targeted for crop improvement.

Key Technological Platforms and Workflows

The field of transcriptomics has evolved rapidly with the development of high-throughput sequencing technologies. The following diagram illustrates a generalized comparative transcriptomics workflow, integrating both sequencing and microarray-based approaches, from experimental design through to data interpretation.

Experimental Design Considerations

The foundation of any robust comparative transcriptomics study lies in its experimental design. Research typically begins with selecting plant varieties with contrasting stress responses—for example, salt-tolerant versus salt-sensitive rice cultivars [2] or cold-tolerant versus cold-sensitive soybean varieties [3]. Replication is critical, with most studies employing three or more biological replicates per condition to account for natural variation and ensure statistical power. Temporal design is another key consideration; capturing multiple time points after stress application (e.g., 0 h, 6 h, 24 h, and 48 h) [2] enables researchers to distinguish early from late stress responses and understand the dynamics of gene regulation.

Transcriptome Profiling Technologies

Two primary technologies dominate transcriptome profiling: microarrays and RNA sequencing (RNA-seq). Microarray technology hybridizes fluorescently labeled cDNA to probes immobilized on a chip, providing a cost-effective method for species with well-annotated genomes. For example, studies on rice panicle development under drought stress used Affymetrix GeneChip microarrays with 57k probe sets to identify drought-responsive genes [4]. RNA sequencing leverages next-generation sequencing platforms to sequence cDNA libraries, offering several advantages including a broader dynamic range, capacity to detect novel transcripts, and capacity for application in species without a reference genome. Recent advances include single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and spatial transcriptomics, which resolve cellular heterogeneity and maintain spatial context—as demonstrated in studies of rice roots adapting to soil stress [5].

Bioinformatics Analysis Pipelines

The analysis of transcriptomic data involves multiple computational steps. For RNA-seq data, quality-controlled reads are aligned to a reference genome using tools like HISAT2 [2], and gene expression is quantified (e.g., using featureCounts) [2]. Differential expression analysis identifies genes with statistically significant expression changes between conditions, typically using tools like DESeq2 [2] with thresholds such as |log2 fold change| ≥ 1 and false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05. For cross-species comparisons or meta-analyses of disparate datasets, specialized pipelines like CoRMAP standardize processing through de novo assembly, orthology assignment with OrthoMCL, and comparative expression analysis of orthologous gene groups [6]. Functional interpretation involves annotating DEGs with Gene Ontology (GO) terms and mapping them to biochemical pathways using databases like Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG).

Comparative Analysis of Transcriptomic Responses to Abiotic Stresses

Salt Stress

Comparative transcriptomics of salt-tolerant (HH11) and salt-sensitive (IR29) rice cultivars under salt stress (200 mM NaCl) revealed both shared and distinct molecular strategies [2]. The following table summarizes key physiological and molecular differences observed.

Table 1: Comparative Responses to Salt Stress in Rice Cultivars

| Parameter | Salt-Tolerant HH11 | Salt-Sensitive IR29 | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antioxidant Enzymes | Higher & sustained GR, GPX activity; Peak SOD/POD at 24h/48h | Strong initial APX spike (6h); Earlier activity peaks | Tolerant cultivar maintains redox homeostasis longer |

| Oxidative Damage | Lower MDA & H2O2 content | Higher MDA & H2O2 content | Tolerant cultivar experiences less cellular damage |

| Osmotic Adjustment | Lower proline accumulation | Higher proline accumulation | Suggests more efficient osmotic regulation in HH11 |

| DEGs in Sucrose/Starch Metabolism | Up-regulation of SS genes, LOC_Os09g12660 | Up-regulation of SPS, GST genes | Distinct metabolic adjustments to maintain energy |

| Key Pathways | Flavonoid biosynthesis, Glutathione metabolism | Glutathione metabolism, Oxidation-reduction | HH11 activates additional protective pathways |

The transcriptomic data revealed that the tolerant HH11 cultivar activated more favorable adjustments in antioxidant and osmotic activity. KEGG enrichment analysis highlighted the importance of sucrose and starch metabolism, flavonoid biosynthesis, and glutathione metabolism in salt tolerance [2]. Specifically, HH11 showed up-regulation of genes like LOC_Os09g12660 (a glucose-1-phosphate adenylyltransferase) and two starch synthase (SS) genes, indicating a reprogramming of carbohydrate metabolism to cope with salt stress.

Drought Stress

Meta-analysis of drought stress studies in tomato identified a core set of 18 meta-DEGs (drought-responsive genes) conserved across multiple experiments and varieties [7]. These genes were enriched in functional categories such as intracellular signal transduction (e.g., Solyc04g076810, Solyc10g076710), ribonuclease P activity, and glycosphingolipid biosynthesis. In rice, comparative transcriptomics of panicles from drought-tolerant and sensitive varieties under water deficit revealed that 76.8% of DEGs were up-regulated across all six studied varieties, with a higher percentage of down-regulated genes in sensitive varieties [4]. Biological process categorization showed that tolerant varieties specifically activated processes related to "regulation of biological quality," "homeostatic process," and "anatomical structure morphogenesis," while sensitive varieties showed unique enrichment in "lipid metabolic process" [4].

Temperature Stress

In soybean, a comparative study of 100 diverse varieties under cold stress identified contrasting tolerant (V100) and sensitive (V45) genotypes [3]. The tolerant V100 outperformed for antioxidant enzyme activities (SOD, POD) and showed higher expression of photosynthesis-related genes (Glyma.08G204800.1, Glyma.12G232000.1), trehalose synthesis genes (GmTPS01, GmTPS13), and established cold marker genes (DREB1E, DREB1D, SCOF-1) [3]. Consequently, V100 exhibited reduced accumulation of reactive oxygen species (H2O2) and malondialdehyde (MDA—a marker for oxidative damage), leading to lower leaf injury. The study also highlighted the role of post-transcriptional regulators, specifically miRNAs like miR319, miR394, miR397, and miR398, in fine-tuning the cold stress response [3].

Comparative Analysis of Transcriptomic Responses to Biotic Stresses

Plants activate broad-spectrum defense mechanisms against biotic stressors. Comparative transcriptomics has elucidated that signaling molecules like salicylic acid (SA), jasmonic acid (JA), and ethylene (ET) are central to these responses, with their production kinetics varying significantly depending on the type of attacker [1]. For instance, in Arabidopsis thaliana, comparative transcriptional profiles revealed considerable overlap between pathogen and insect-induced mutations, suggesting shared defense pathways [1].

In cotton, transcriptomic analysis of response to whitefly infestation identified WRKY40 and a transport protein as hub genes regulating defense [1]. Functional validation showed that silencing GhMPK3 suppressed the MPK-WRKY-JA and ET pathways, leading to enhanced susceptibility to whiteflies [1]. Another powerful example is the expression of the transcription factor AtMYB12 from A. thaliana in tobacco, which resulted in enhanced expression of phenylpropanoid pathway genes and increased accumulation of flavonols, particularly rutin [1]. This metabolic engineering conferred resistance to pests like Spodoptera litura and Helicoverpa armigera, demonstrating how comparative transcriptomics can identify key regulatory genes for crop protection.

Signaling Pathways in Stress Response: A Visual Synthesis

The molecular response to stress is orchestrated by complex signaling pathways that integrate hormone signaling, transcriptional regulation, and physiological outputs. The following diagram synthesizes the key pathways and their interactions, as revealed by comparative transcriptomic studies.

This integrative view shows how comparative transcriptomics identifies components across multiple regulatory layers. For example, the diagram highlights how the CYP734A gene family (e.g., CYPT in Primula), which degrades brassinosteroids, regulates cell wall remodeling and style length in distylous species, a mechanism co-opted in stress responses [8]. Similarly, transcription factors like DREB/CBF are master regulators activated under cold and drought, controlling downstream genes involved in osmoprotection and antioxidant defense [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful comparative transcriptomics studies rely on a suite of trusted reagents and methodologies. The following table catalogs key solutions derived from the analyzed studies.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Comparative Transcriptomics

| Reagent / Solution | Primary Function | Specific Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| TRIzol Reagent | Total RNA extraction from plant tissues | Used for RNA extraction from rice seedlings prior to Illumina sequencing [2]. |

| Yoshida Nutrient Solution | Standardized hydroponic plant growth | Used for cultivating rice seedlings before applying salt stress (200 mM NaCl) [2]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Induction of osmotic/drought stress in lab | Used as PEG6000 to simulate drought stress in sweet potato, identifying 11,359 DEGs [1]. |

| NEBNext Ultra RNA Library Prep Kit | Preparation of sequencing-ready RNA libraries | Used for constructing cDNA libraries for Illumina sequencing in rice salt stress studies [2]. |

| Affymetrix GeneChip Microarrays | Genome-wide expression profiling | Used for profiling gene expression in young rice panicles under drought stress [4]. |

| 10X Genomics scRNA-seq Platform | Single-cell transcriptome profiling | Used to profile >47,000 rice root cells to study cell-type-specific soil stress responses [5]. |

| SYBR Green Master Mix | Quantitative PCR (qPCR) validation of DEGs | Used to validate microarray results; correlation with microarray data was 0.91-0.99 [4]. |

| Trim Galore! / FastQC | Quality control and adapter trimming of raw reads | Part of the CoRMAP pipeline for standardizing RNA-seq meta-analysis [6]. |

Comparative transcriptomics has established itself as an indispensable framework for deconstructing the complex molecular dialogues that underlie plant stress tolerance. By systematically comparing gene expression profiles between susceptible and tolerant varieties, this approach moves beyond cataloging individual genes to revealing interconnected networks and key regulatory hubs. The power of this methodology is evidenced by its consistent success in identifying conserved and specific pathways—from hormone signaling and antioxidant defense to specialized metabolism and transcriptional regulation—that can be targeted for crop improvement. As technologies evolve toward single-cell and spatial resolution, and as analytical methods become more sophisticated through meta-analysis and multi-omics integration, comparative transcriptomics is poised to deliver even deeper insights. These advances will accelerate the development of climate-resilient crops, ultimately supporting global food security in the face of mounting environmental challenges.

Comparative transcriptomics has emerged as a powerful approach for unraveling the molecular mechanisms underlying complex traits in plants, particularly disease resistance and stress tolerance. By analyzing global gene expression patterns in susceptible and tolerant varieties under stress conditions, researchers can identify key differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and pathways that contribute to adaptive responses. This guide examines the experimental frameworks, methodologies, and analytical techniques used in comparative transcriptomic studies, providing a structured overview of how DEG identification drives discovery in plant stress biology. Through case studies across diverse plant-pathogen systems and abiotic stresses, we explore how this "tale of two varieties" approach reveals the genetic basis of contrasting phenotypes, offering valuable insights for crop improvement strategies.

DEG Patterns Across Plant Species and Stress Conditions

The table below summarizes differential gene expression patterns from recent comparative transcriptomic studies investigating susceptible/resistant and tolerant/sensitive plant varieties under various stress conditions.

Table 1: Comparative DEG Profiles Across Plant Species and Stress Conditions

| Plant Species | Stress Condition | Tolerant/Resistant Variety | Susceptible/Sensitive Variety | Key Findings | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rutaceae (Citrus) | Huanglongbing (HLB) | Punctate Wampee (1611 ↑, 1727 ↓ DEGs) | Ponkan Mandarin (1519 ↑, 700 ↓ DEGs) | Resistant variety showed stronger regulation of cellular homeostasis; susceptible activated lignin synthesis | [9] |

| Chinese cabbage | Clubroot (Pathotype 11) | JP variety (4211 ↑, 5222 ↓ DEGs) | 83-1 variety (2781 ↑, 3675 ↓ DEGs) | Resistant cultivar activated hormone signaling, secondary metabolism, and cell wall fortification | [10] |

| Alfalfa | Atrazine herbicide | JN5010 (Shoots: 2297 ↑, 3167 ↓; Roots: 3232 ↑, 4907 ↓ DEGs) | WL363 (Shoots: 2937 ↑, 4237 ↓; Roots: 5316 ↑, 7977 ↓ DEGs) | Tolerant variety maintained stable expression in antioxidant and detoxification pathways | [11] [12] |

| Soybean | Salt stress | PI 561363 (480h: 4561 DEGs) | PI 601984 (480h: 5479 DEGs) | Tolerant genotype enriched ion transport, ethylene signaling, suberin biosynthesis | [13] |

| Wild vs. cultivated tomato | Hypoxia | T178 wild (1238 ↑, 1113 ↓ DEGs) | Fenzhenzhu cultivated (1326 ↑, 1605 ↓ DEGs) | Wild tomato upregulated carbohydrate metabolism; cultivated variety activated transcription machinery | [14] |

Experimental Design and Methodologies

Standardized Workflow for Comparative Transcriptomics

The identification of meaningful DEG patterns relies on carefully controlled experimental designs and standardized workflows. Most comparative transcriptomic studies follow a similar pipeline from biological design through data interpretation, though specific applications vary based on the research question and plant system.

Diagram: Transcriptomic Analysis Workflow for DEG Identification

Key Methodological Components

Plant Materials and Stress Treatments

Comparative transcriptomic studies require careful selection of genetically distinct varieties with clearly contrasting phenotypes. For instance, in the Huanglongbing study, researchers selected Ponkan Mandarin as susceptible and Punctate Wampee as resistant varieties, growing two-year-old seedlings under controlled greenhouse conditions [9]. Similarly, the hypoxia response study in tomatoes utilized wild accession T178 (Solanum habrochaites) and cultivated variety Fenzhenzhu (Solanum lycopersicum) to exploit natural genetic variation [14].

Stress application methods are tailored to the specific research question:

- Pathogen stress: In the Rutaceae-HLB study, inoculation was performed via grafting with CLas-infected scions [9]

- Chemical stress: The alfalfa-atrazine study applied 2.0 mg/L atrazine in hydroponic systems for six days [12]

- Abiotic stress: Soybean salt stress studies utilized 150 mM NaCl treatment at the V2 stage [13]

Sampling timepoints are critical for capturing meaningful transcriptional responses. The Chinese cabbage-clubroot study identified 14 days post-inoculation as a critical timepoint for resistance response [10], while the soybean salt stress study implemented a time-series approach at 0h, 6h, 24h, and 48h to capture both early and late responses [13].

RNA Sequencing and Quality Control

RNA extraction typically utilizes commercial kits such as Qiagen RNeasy Plant Mini Kit or TRIzol Reagent, with rigorous quality assessment measures including:

- RNA Integrity Number (RIN) > 7.0 [9]

- OD260/280 ratios between 1.8-2.1 [9] [12]

- Agarose gel electrophoresis for integrity confirmation [9]

Library preparation commonly employs Illumina TruSeq RNA Sample Preparation Kits with poly(A) selection for mRNA enrichment [9] [12]. Sequencing is predominantly performed on Illumina platforms (HiSeq, NovaSeq) generating 150bp paired-end reads, with read depths typically ranging from 20-40 million reads per sample to ensure statistical power for DEG detection.

Analytical Approaches for DEG Identification

Bioinformatics Pipelines

The transition from raw sequencing data to biologically meaningful DEG sets involves multiple computational steps. Quality control of raw reads is performed using tools like FastQC, followed by adapter trimming and quality filtering. Reads are then aligned to reference genomes using splice-aware aligners such as STAR or HISAT2. For plants without reference genomes, de novo transcriptome assembly can be performed using Trinity or similar tools.

DEG identification typically employs statistical packages like DESeq2, edgeR, or limma, which model count data and account for biological variability. These tools apply statistical tests (often with negative binomial distributions) to identify genes with significant expression changes between conditions, using adjusted p-values (e.g., FDR < 0.05) and minimum fold-change thresholds (typically |log2FC| > 1) to control false discoveries.

Functional Annotation and Pathway Analysis

Once DEGs are identified, functional interpretation is essential. Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis categorizes DEGs into biological processes, molecular functions, and cellular components. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis maps DEGs to known metabolic and signaling pathways. As demonstrated in the Huanglongbing study, these analyses reveal how resistant and susceptible varieties deploy different biological pathways—with Ponkan Mandarin activating lignin synthesis while Punctate Wampee regulated cellular homeostasis [9].

Advanced network-based approaches like Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) identify modules of highly correlated genes and their association with traits of interest. In the Rutaceae study, WGCNA identified ten potential key resistance genes in Punctate Wampee, including genes involved in lignin biosynthesis and cellular signaling [9].

Defense Mechanisms Revealed by Comparative Transcriptomics

Integrated Defense Response Pathways

Comparative transcriptomic analyses across multiple plant systems have revealed conserved yet customized defense strategies in resistant varieties. The integrated defense response involves coordinated activation of specific pathways that contribute to resistance phenotypes.

Diagram: Defense Signaling Pathways in Resistant Varieties

Key Defense Strategies Across Plant Systems

Transcriptional Reprogramming and Transcription Factors

Resistant varieties consistently show enhanced and coordinated upregulation of defense-associated transcription factors. The Huanglongbing study identified WRKY, ERF, and MYB transcription factors as commonly regulated in both susceptible and resistant varieties, but with distinct temporal patterns and target genes [9]. In barley, the HvbZIP87 transcription factor was found to physically interact with NPR1 in the nucleus and directly regulate pathogenesis-related (PR) genes and zinc transporters, conferring broad-spectrum resistance [15].

Hormonal Signaling Networks

The balance between salicylic acid (SA) and jasmonic acid (JA) signaling pathways often differentiates resistant and susceptible responses. In barley meta-analyses, 70% of common DEGs between fungal and aphid responses were uniquely regulated by JA or SA signaling, while 30% were co-regulated by both hormones [16]. Chinese cabbage resistance to clubroot involved ABA-mediated adaptation to water scarcity induced by the pathogen [10].

Structural and Chemical Barriers

Resistant varieties often enhance physical barriers through cell wall fortification and chemical defenses through secondary metabolites. The alfalfa atrazine tolerance study revealed differential regulation of phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, with sensitive varieties downregulating lignin biosynthesis genes [12]. In the Chinese cabbage-clubroot system, the resistant JP variety inhibited pathogen proliferation in xylem vessels through activation of secondary metabolite production and cell wall reinforcement [10].

Oxidative Stress Management

Effective reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenging differentiates tolerant varieties under abiotic stress. The atrazine-tolerant alfalfa variety maintained higher antioxidant enzyme activities and lower MDA content (a lipid peroxidation marker), supported by upregulation of genes involved in proline metabolism and the S-adenosylmethionine cycle [12]. Similarly, salt-tolerant soybean genotypes maintained lower POX activity and MDA levels under stress [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for Comparative Transcriptomic Studies

| Category | Specific Product/Kit | Application in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction | Qiagen RNeasy Plant Mini Kit | High-quality total RNA extraction from plant tissues | Used in Rutaceae-HLB study [9] |

| RNA Quality Control | Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer | RNA Integrity Number (RIN) assessment | Quality control in alfalfa atrazine study [12] |

| Library Preparation | Illumina TruSeq RNA Sample Preparation Kit | cDNA library construction for sequencing | Standard protocol in multiple studies [9] [12] |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NovaSeq/HiSeq | High-throughput paired-end sequencing | 150bp reads in soybean salt stress study [13] |

| DNase Treatment | DNase I (TaKaRa) | Genomic DNA removal from RNA samples | Essential step in alfalfa transcriptomics [12] |

| Validation | Solarbio Biochemical Assay Kits | Physiological parameter measurement | Chlorophyll and soluble sugar assays [12] |

| Hormone Analysis | Abbkine Enzyme Activity Kits | Antioxidant enzyme activity measurement | SOD and MDA assays in alfalfa [12] |

Comparative transcriptomics of susceptible and tolerant varieties provides a powerful framework for identifying key genetic determinants of stress responses in plants. The consistent patterns emerging across diverse systems—including coordinated transcription factor regulation, hormonal signaling cross-talk, structural barrier enhancement, and oxidative stress management—highlight conserved defense strategies while revealing system-specific adaptations. The experimental and analytical methodologies summarized in this guide provide a roadmap for designing robust comparative transcriptomic studies that can bridge the gap between phenotype and genotype. As these approaches continue to evolve with advancing sequencing technologies and multi-omics integration, they offer increasingly powerful tools for uncovering the molecular basis of stress resilience and accelerating the development of improved crop varieties.

In comparative transcriptomics, researchers identify hundreds to thousands of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between susceptible and tolerant plant varieties. While these gene lists are valuable, they represent merely the starting point for biological discovery. The crucial next step involves determining which biological processes, molecular functions, and pathways are statistically overrepresented in these gene sets—a methodological approach known as pathway enrichment analysis [17] [18].

Within the context of plant-pathogen interactions, enrichment analysis provides the critical link between raw gene expression data and mechanistic biological understanding. By applying frameworked annotations from Gene Ontology (GO) and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), researchers can determine whether defense-related pathways are systematically activated in resistant varieties, revealing the molecular basis of disease resilience [9] [19]. This guide objectively compares GO and KEGG enrichment methodologies, supported by experimental data from plant transcriptomic studies, to help researchers select appropriate tools for extracting biological meaning from their gene lists.

GO and KEGG: Complementary Analytical Frameworks

Gene Ontology (GO) and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) represent distinct but complementary approaches to functional annotation. GO classifies gene functions across three structured, independent vocabularies: Biological Process (BP), Molecular Function (MF), and Cellular Component (CC) [17] [18]. Alternatively, KEGG maps genes within the context of specific metabolic or signaling pathways, revealing how multiple gene products work together in biological systems [17].

The following table summarizes the core distinctions between these two enrichment approaches:

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between GO and KEGG Enrichment Analysis

| Feature | GO Enrichment | KEGG Enrichment |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Focus | Functional ontology | Pathway-centric |

| Primary Output | Functional terms (BP/MF/CC) | Pathway maps/diagrams |

| Main Application | Gene role classification & functional characterization | Systemic pathway insights & metabolic interactions |

| Statistical Method | Hypergeometric test | Hypergeometric/Fisher's exact test |

| Structural Nature | Hierarchical directed acyclic graph | Network-based pathway diagrams |

Comparative Analysis in Action: Experimental Evidence from Plant Studies

Case Study 1: Huanglongbing Disease in Rutaceae Plants

A comparative transcriptomic study of HLB-susceptible Ponkan Mandarin and HLB-resistant Punctate Wampee revealed distinct defense strategies through GO and KEGG analysis. The susceptible Ponkan Mandarin primarily activated pathways related to lignin synthesis and cell wall modification, attempting to physically block pathogen spread. In contrast, the resistant Punctate Wampee regulated cellular homeostasis and metabolic processes, demonstrating a more sophisticated defense approach [9].

The experimental protocol for this investigation included:

- Plant Material & Inoculation: Two-year-old seedlings were inoculated with Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus (CLas) via grafting. Control and infected leaves were collected at 1.5 months post-inoculation [9].

- RNA Sequencing: Total RNA extraction using Qiagen RNeasy Plant Mini Kit with DNase I treatment. Library preparation with Illumina TruSeq RNA Sample Preparation Kit and sequencing on Illumina platforms [9].

- Enrichment Analysis: DEGs were identified and analyzed through GO enrichment and KEGG pathway analysis to determine overrepresented functions and pathways in each variety's response [9].

Case Study 2: Botrytis cinerea Infection in Grapevine

Transcriptomic analysis of Botrytis cinerea tolerance in grapevine genotypes demonstrated the value of temporal analysis in pathway enrichment. Researchers identified critical pathways including phenylpropanoid biosynthesis (lignin metabolism) and MAPK signaling through KEGG analysis [19]. The tolerant genotype showed enhanced modulation of metabolic processes by the second time point (T2), prioritizing secondary metabolism and stress adaptation over growth [19].

The experimental workflow for this study incorporated:

- Time-Series Design: Sample collection at multiple post-inoculation time points (T0 prior to inoculation, T1 at 24h, T2 at 48h, T3 at 5 days) to capture dynamic transcriptional responses [19].

- Pathogen Inoculation: Surface-sterilized berries were inoculated with B. cinerea conidial suspension (1×10⁵ conidia mL⁻¹) to ensure consistent infection pressure [19].

- Integrated Analysis: GO and KEGG enrichment identified key defense mechanisms, with transcription factors WRKY and MYB highlighted as central regulators in the tolerant genotype [19].

The following diagram illustrates the general analytical workflow for comparative transcriptomic studies incorporating GO and KEGG enrichment:

Pathway Enrichment Analysis Workflow

Quantitative Comparison of Enrichment Results

The table below synthesizes enrichment findings from multiple plant transcriptomic studies, demonstrating how GO and KEGG reveal different aspects of the biological response:

Table 2: Enrichment Results from Comparative Transcriptomic Studies of Plant Defense

| Plant System | Stress Condition | Key GO Enrichment Findings | Key KEGG Pathway Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rutaceae Plants [9] | Huanglongbing disease | Lignin synthesis, cell wall modification (susceptible); Cellular homeostasis (resistant) | Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, Plant-pathogen interaction |

| Grapevine [19] | Botrytis cinerea (gray mold) | Secondary metabolic process, response to stress | Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, MAPK signaling pathway |

| Soybean [13] | Salt stress | Ion transport, ethylene signaling, lipid biosynthesis | Starch and sucrose metabolism, Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis |

| Alfalfa [12] | Atrazine herbicide | Proline metabolic process, S-adenosylmethionine cycle | Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, Flavonoid biosynthesis |

Methodological Protocols for Enrichment Analysis

Standard Analytical Workflow

A robust enrichment analysis follows a systematic process from gene list to biological interpretation:

DEG Identification: Generate DEG lists from expression data using tools like DESeq2 or edgeR with appropriate significance thresholds (e.g., FDR < 0.05, log2FC > 1) [9] [13].

Background Specification: Define appropriate background gene set, typically all genes detected in the RNA-seq experiment, to avoid bias toward highly annotated genes [20].

Enrichment Calculation: Apply hypergeometric test or Fisher's exact test to identify overrepresented GO terms/KEGG pathways in DEGs compared to background [20].

Multiple Testing Correction: Adjust p-values using Benjamini-Hochberg FDR control to account for testing thousands of terms simultaneously [20].

Result Interpretation: Filter significant terms (FDR < 0.05), consider fold enrichment values, and visualize relationships between terms using tree plots or network graphs [20].

Visualization Techniques for Enrichment Results

Effective visualization enhances interpretation of enrichment results:

- Barplots/Bubble Charts: Display top enriched terms with statistical significance (p-value/FDR), gene counts, and enrichment factors [17].

- Tree Plots: Hierarchical clustering of significant GO terms based on shared genes reveals functional clusters and parent-child relationships [20].

- Network Graphs: Interactive plots show connections between enriched pathways where edges represent gene overlaps [20].

- KEGG Pathway Diagrams: Visualize user's genes highlighted in red within specific pathway contexts [20].

The following diagram illustrates the key defense pathways commonly enriched in resistant plant varieties:

Defense Pathways in Resistant Plants

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Enrichment Analysis

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| TRIzol Reagent [12] | RNA extraction from plant tissues | Maintain RNA integrity; prevent degradation during isolation |

| Illumina TruSeq RNA Kit [9] [12] | cDNA library preparation for RNA-seq | Poly(A) selection for mRNA enrichment; fragmentation optimization |

| clusterProfiler [18] | R package for GO/KEGG enrichment | Supports multiple species; provides publication-ready visualizations |

| ShinyGO [20] | Web-based enrichment tool | User-friendly interface; supports 14,000 species; no coding required |

| NanoDrop Spectrophotometer [9] [12] | RNA quality assessment | OD260/280 ratios of 1.8-2.1 indicate pure RNA |

| Agilent Bioanalyzer [9] [12] | RNA Integrity Number (RIN) determination | RIN >7.0 required for high-quality RNA-seq libraries |

| Hypergeometric Test [20] | Statistical foundation for enrichment | Determines probability of observed overlap between gene sets |

GO and KEGG enrichment analyses provide complementary approaches for extracting biological meaning from gene lists generated in comparative transcriptomic studies. GO offers comprehensive functional annotation across biological processes, molecular functions, and cellular components, while KEGG provides systemic pathway insights with valuable visual contextualization [17]. Experimental evidence from plant-pathogen systems demonstrates that resistant varieties typically show enhanced and coordinated enrichment of defense-related pathways, including phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, MAPK signaling, and pathogenesis-related protein production [9] [19].

Selection between these methods should be guided by research objectives: GO is ideal for comprehensive functional characterization of DEGs, while KEGG is preferred for exploring specific metabolic or signaling interactions [17]. For a complete analytical picture, researchers often combine both methods, starting with GO for broad functional annotation, then using KEGG for pathway exploration, and potentially incorporating GSEA for detecting subtle coordinated expression changes across entire gene sets [17]. This multi-faceted approach maximizes biological insights from transcriptomic data, accelerating the discovery of molecular mechanisms underlying disease resistance in plants.

Citrus Huanglongbing (HLB), also known as citrus greening, is the most devastating disease threatening global citrus production [21] [22]. The disease is associated with the phloem-limited, unculturable gram-negative bacterium 'Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus' (CLas) [21]. HLB-affected trees exhibit symptoms including yellow shoots, leaf mottling, misshapen fruits with color inversion, and ultimately tree decline [23]. With no effective cure available, breeding HLB-tolerant citrus varieties represents one of the most promising long-term strategies for disease management [21] [24]. This case study employs comparative transcriptomics to dissect the differential defense mechanisms between resistant and susceptible citrus genotypes, providing molecular insights for future breeding programs.

Experimental Design and Methodologies

Plant Materials and CLas Inoculation

Multiple studies have employed similar rigorous greenhouse assays to evaluate citrus response to CLas infection. A typical protocol involves using two-year-old CLas-free seedlings of various citrus genotypes grafted onto appropriate rootstocks [21]. For each cultivar, approximately 15 seedlings are grafted with CLas-infected budwoods, while 5 control seedlings are mock-grafted with budwood from healthy plants [21]. The CLas-infected budwoods are typically collected from HLB-affected trees and confirmed by CLas-specific quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) prior to grafting [21]. After grafting, all plants are maintained in insect-proof greenhouses under controlled conditions, with fertilizer applied as needed [21].

Table 1: Experimental Designs in Key Transcriptomic Studies of Citrus HLB

| Study Reference | Tolerant Genotypes | Susceptible Genotypes | Inoculation Method | Sampling Time Points |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frontiers in Plant Science 2023 [21] | C. limon (Eureka lemon), C. maxima (Shatian pomelo) | C. reticulata Blanco (Shatangju mandarin), C. sinensis (Hongjiang orange) | Grafting with CLas-infected budwoods | 12 weeks post-grafting (wpg) - early stage; 48 wpg - late stage |

| Phytopathology 2023 [25] | 'LB8-9' Sugar Belle mandarin | Valencia sweet orange | Natural infection in field conditions | Seasonal: Winter, Spring, Summer, Fall |

| PLOS ONE 2017 [26] | C. hystrix (Kaffir lime) | C. sinensis (Pineapple sweet orange) | Bud grafting with CLas-infected material | 3 months post-inoculation |

Sample Collection and Nucleic Acid Extraction

For transcriptomic analyses, leaf samples are typically collected at specific time points post-inoculation. Researchers often collect six complete leaves per plant, including three close to grafting budwoods and three from new flush [21]. For RNA-Seq, midribs from multiple leaves are dissected and mixed as one sample. Total RNA extraction is performed using commercial kits such as the E.Z.N.A. Total RNA Kit I, with RNA quality assessed using Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer and concentration measured by Qubit 2.0 or Nanodrop spectrophotometer [21] [26]. DNA extraction for CLas quantification typically uses 100 mg of fresh leaf midrib tissue processed with commercial DNA extraction kits [21].

RNA Sequencing and Data Analysis

For transcriptome profiling, cDNA libraries are constructed using Illumina TruSeq RNA Sample Preparation Kit following poly(A)+ mRNA isolation [9]. Sequencing is performed on platforms such as MGISEQ-200 or Illumina sequencers [21] [27]. After quality control, clean reads are mapped to reference citrus genomes using alignment tools like Bowtie 2 or HISAT2 [26] [27]. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) are identified using thresholds such as false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05 and |log2 fold change| ≥ 1 [21] [26]. Functional enrichment analysis is performed using Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) databases [9] [26].

Key Findings: Transcriptional Differences Between Resistant and Susceptible Varieties

Global Transcriptomic Responses

Comparative transcriptome analyses consistently reveal significant variation in DEGs between susceptible and tolerant cultivar groups at both early and late infection stages [21]. The number of DEGs is often greater in susceptible varieties compared to tolerant ones when compared to their respective healthy controls [26]. Seasonal transcriptome profiling further indicates that the highest number of DEGs is typically found in spring for both tolerant and susceptible cultivars [25].

Table 2: Summary of Differentially Expressed Genes in Selected Studies

| Study | Tolerant Cultivar | Susceptible Cultivar | Up-regulated DEGs | Down-regulated DEGs | Key Activated Pathways |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PMC10301834 [21] | C. limon & C. maxima | C. reticulata Blanco & C. sinensis | Varies by timepoint | Varies by timepoint | SA-mediated defense, PTI, cell wall immunity, phenylpropanoid metabolism |

| PLOS ONE 2017 [26] | C. hystrix (Kaffir lime) | C. sinensis (Sweet orange) | 179 | 73 | Cell wall metabolism, secondary metabolism, peroxidases |

| MDPI Agronomy 2025 [9] | Punctate Wampee | Ponkan Mandarin | 1611 | 1727 | Cellular homeostasis, metabolism, lignin biosynthesis |

Defense Signaling Pathways

Salicylic Acid-Mediated Defense: Tolerant cultivars consistently exhibit stronger activation of SA-mediated defense response [21]. WRKY transcription factors, key regulators of SA signaling, show distinct expression patterns between tolerant and susceptible genotypes [28]. The nonexpressor of pathogenesis-related genes 1 (NPR1), a master regulator of systemic acquired resistance, is often more highly expressed in resistant varieties [9].

Pattern-Triggered Immunity (PTI): Tolerant citrus genotypes demonstrate enhanced pattern-triggered immunity, characterized by upregulation of receptor-like kinases (RLKs) and calcium-dependent protein kinases (CDPKs) [21] [25]. These genes are involved in early pathogen recognition and activation of downstream defense responses.

Jasmonic Acid/Ethylene Signaling: Contrasting responses are observed in jasmonic acid (JA) and ethylene pathways. Some tolerant varieties exhibit upregulation of JA signaling genes [24], while susceptible cultivars often show overexpression of genes involved in ethylene metabolism, potentially contributing to early symptom development [21].

Physiological and Structural Defense Mechanisms

Cell Wall Fortification: Tolerant cultivars consistently upregulate genes involved in cell wall reinforcement, including those encoding cellulose synthases, cell wall proteins, and lignin biosynthesis enzymes [21] [9] [26]. This creates a physical barrier that may limit pathogen spread.

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Management: Effective ROS scavenging is a hallmark of tolerant varieties. Genes encoding catalases, ascorbate peroxidases, Cu/Zn superoxide dismutases, and other peroxidases are significantly upregulated in tolerant genotypes, helping to mitigate oxidative stress caused by CLas infection [21] [26]. HLB-tolerant mandarin 'LB8-9' also contains higher concentrations of maltose and sucrose, which are known to scavenge ROS [25].

Antibacterial Secondary Metabolism: Tolerant varieties activate pathways for producing antimicrobial compounds, including phenylpropanoids, flavonoids, and terpenoids [21] [24]. These secondary metabolites directly inhibit pathogen growth and enhance plant defense capacity.

Phloem Regeneration: Anatomical studies and transcriptome analyses reveal that phloem regeneration contributes to HLB tolerance in some varieties like 'LB8-9' Sugar Belle mandarin [25]. This helps counteract the phloem plugging and collapse characteristic of HLB pathogenesis [23].

Diagram 1: HLB Defense and Symptom Development Pathways in Citrus. This diagram contrasts effective defense activation in tolerant varieties (green) with pathological responses leading to symptoms in susceptible varieties (red).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Citrus HLB Transcriptomics

| Category | Specific Product/Kit | Application in HLB Research |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction | E.Z.N.A. HP Plant DNA Kit [21] | High-quality DNA extraction for CLas detection |

| E.Z.N.A. Total RNA Kit I [21] | Total RNA extraction from citrus midribs | |

| Qiagen RNeasy Plant Mini Kit [9] | RNA extraction with on-column DNase digestion | |

| CLas Detection | CLas-specific qPCR (CLas4G/HLBr primers) [21] | Accurate quantification of bacterial titer |

| TaqMan qPCR assays [26] | Sensitive CLas detection with probe-based chemistry | |

| RNA-Seq Library Prep | Illumina TruSeq RNA Sample Preparation Kit [9] | cDNA library construction for transcriptome sequencing |

| Reference Genomes | Citrus sinensis genome (CPBD v3.0) [27] | Reference for read alignment and DEG identification |

| Citrus Pan-genome to Breeding Database [28] | Resource for gene family analysis (e.g., WRKY TFs) |

Comparative transcriptomics of resistant and susceptible citrus varieties has revealed a multifaceted defense strategy against HLB. Tolerant genotypes typically employ earlier and more coordinated activation of defense pathways including SA-mediated signaling, PTI, cell wall reinforcement, ROS scavenging, and production of antimicrobial compounds. The identification of key transcription factors such as WRKY, ERF, and MYB families, along with structural genes involved in lignin biosynthesis and phloem regeneration, provides valuable targets for marker-assisted breeding. Future research should focus on validating the functional roles of candidate resistance genes through genetic transformation and genome editing technologies. The integration of transcriptomic data with metabolomic and proteomic analyses will further illuminate the complete molecular landscape of citrus-CLas interactions, accelerating the development of durable HLB-resistant citrus varieties.

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Citrus HLB Transcriptomics. This diagram outlines the key steps in a standard transcriptome analysis pipeline for studying citrus-HLB interactions, from sample collection to data validation.

This case study investigates the conserved molecular networks that underlie salt tolerance in soybean (Glycine max L.) through a comparative transcriptomics approach. By analyzing the differential responses of salt-tolerant and salt-sensitive genotypes across multiple studies, we identify core signaling pathways, regulatory genes, and physiological mechanisms that constitute the soybean salt stress response system. Our integrated analysis reveals conserved patterns in ion transport, reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenging, phytohormone signaling, and transcriptional reprogramming that distinguish tolerant from susceptible varieties. The findings provide a framework for targeted breeding strategies and development of salt-resilient soybean cultivars through molecular-assisted selection and genetic engineering.

Soil salinity represents a significant abiotic stress that severely limits soybean productivity worldwide, with yield reductions exceeding 40% under high salt conditions [29] [30]. Soybean exhibits moderate tolerance to saline conditions, but considerable genetic variation exists among germplasm accessions, enabling identification of key tolerance mechanisms through comparative analysis [13] [31]. Understanding the conserved molecular networks that confer salt tolerance across diverse genetic backgrounds is crucial for developing climate-resilient soybean varieties.

Comparative transcriptomics of susceptible and tolerant plant varieties provides powerful insights into the genetic architecture of complex traits such as salt tolerance [32] [33]. This approach enables researchers to distinguish stress-responsive pathways from general stress reactions and identify core regulatory mechanisms that consistently operate in tolerant genotypes. Recent advances in RNA sequencing technologies have facilitated comprehensive investigations of the temporal dynamics of gene expression under salt stress, revealing intricate signaling networks and regulatory hierarchies [13] [30] [33].

Experimental Designs and Methodologies

Genotype Selection and Stress Applications

Across the studies analyzed, researchers employed consistent criteria for selecting contrasting soybean genotypes based on established salt tolerance indices, including leaf scorching scores, ion accumulation patterns, and survival rates [13] [29] [30].

Table 1: Soybean Genotypes and Salt Stress Protocols in Transcriptomic Studies

| Study Reference | Tolerant Genotype | Sensitive Genotype | Salt Concentration | Time Points Analyzed | Tissues Sampled |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scientific Reports (2025) [13] | PI 561363 | PI 601984 | 150 mM NaCl | 0 h, 6 h, 24 h, 48 h | Leaves |

| IJMS (2024) [30] | Xin No. 9 (X9) | Xinzhen No. 9 (Z9) | 300 mM NaCl | 0 h, 1 h, 6 h, 12 h, 24 h | Roots, Leaves |

| BMC Plant Biology (2022) [33] | Qi Huang No.34 (QH34) | Dong Nong No.50 (DN50) | 150 mM NaCl | 2 h, 4 h, 8 h | Roots |

Salt stress was typically applied at the V2 developmental stage using hydroponic systems or sand culture with nutrient solutions [13] [33]. The selected salt concentrations (150-300 mM NaCl) effectively discriminated between tolerant and sensitive phenotypes without causing immediate lethality, enabling observation of transcriptional reprogramming across multiple time points.

Transcriptomic Profiling and Bioinformatics

All studies utilized RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) for comprehensive transcriptome profiling. Key methodological aspects included:

- RNA Extraction and Library Preparation: High-quality total RNA was extracted using commercial kits (e.g., Direct-zol RNA Miniprep, RNeasy Plant Mini Kit) and assessed for purity and integrity [13] [34]. Sequencing libraries were prepared with Illumina platform-compatible protocols.

- Sequencing Parameters: Paired-end sequencing (2×150 bp) was performed on Illumina platforms (NovaSeq X Plus, HiSeq) with minimum sequencing depth of 20 million reads per sample [13] [30] [33].

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Quality-controlled reads were aligned to reference genomes (Williams 82 a2 v1) using TopHat2 or HISAT2. Differential expression analysis was conducted with DESeq2 or edgeR, with false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05 and |log2FC| > 1 as significance thresholds [13] [33].

- Functional Annotation: Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analyses identified biological processes, molecular functions, and pathways significantly enriched in differentially expressed genes (DEGs) [13] [30] [33].

Physiological and Biochemical Validation

Transcriptomic findings were validated through physiological and biochemical assessments:

- Chlorophyll Content: Measured using SPAD meters or spectrophotometric methods, with tolerant genotypes maintaining higher levels under stress [13] [30].

- Malondialdehyde (MDA): Lipid peroxidation indicator quantified via thiobarbituric acid reaction, with lower levels in tolerant genotypes [13].

- Antioxidant Enzymes: Peroxidase (POX) activity assessed spectrophotometrically using guaiacol as substrate [13].

- Ion Content: Leaf Na+, K+, and Cl- concentrations measured via ion chromatography or flame photometry [29].

- Photosynthetic Parameters: Chlorophyll fluorescence (Fv/Fm, Y(II), Y(NPQ)) evaluated using imaging PAM systems [30].

Conserved Transcriptional Networks in Salt Tolerance

Temporal Dynamics of Differential Gene Expression

Comparative transcriptomics revealed distinct temporal patterns of gene expression between salt-tolerant and sensitive genotypes. Tolerant genotypes typically exhibited earlier and more coordinated transcriptional responses, with the highest number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) observed at 48 hours after salt stress [13].

Table 2: Temporal Dynamics of Differential Gene Expression in Salt-Stressed Soybean

| Genotype Comparison | Early Response (2-6 h) | Mid Response (24 h) | Late Response (48 h) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PI 561363 (Tolerant) | 1,807 DEGs | 786 DEGs | 4,561 DEGs | Sustained upregulation of ion transporters and TF genes [13] |

| PI 601984 (Sensitive) | 1,465 DEGs | 681 DEGs | 5,479 DEGs | Delayed response with predominant stress-associated genes [13] |

| QH34 (Tolerant) | More DEGs at 4h and 8h | Progressive activation | Coordinated regulation | Earlier and more organized transcriptome reorganization [33] |

| DN50 (Sensitive) | More DEGs at 2h | Limited adjustment | Disorganized response | Immediate but uncoordinated stress reaction [33] |

Tolerant genotypes displayed a more organized transcriptome reorganization, with sequential activation of specific pathways across time points. In contrast, sensitive genotypes showed either delayed responses or immediate but uncoordinated stress reactions that failed to establish homeostasis [13] [33].

Core Conserved Pathways in Salt Tolerance

Integration of multiple transcriptomic studies identified consistently dysregulated pathways in salt-tolerant soybean genotypes:

- Ion Transport and Homeostasis: Enrichment of genes encoding high-affinity potassium transporters (GmHAK5, GmKUP6), cation/H+ exchangers (GmCHX20a), and salt tolerance-associated genes (GmTDT) [13].

- ROS Scavenging Systems: Upregulation of glutathione S-transferases (GmGSTU19), peroxidases, and superoxide dismutases in tolerant genotypes [13] [30].

- Phytohormone Signaling: ABA-dependent and independent pathways, with key roles for ethylene-responsive factors (GmERF98, GmERF1) [13] [31].

- Osmotic Adjustment: Genes involved in proline biosynthesis, sugar metabolism, and late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) proteins [30] [31].

- Transcription Factors: Significant enrichment of HSF, WRKY, NAC, and MYB family transcription factors [33] [31].

Genotype-Specific Transcriptional Strategies

While conserved networks exist, transcriptomic analyses also revealed genotype-specific strategies for salt tolerance:

- Xinjiang Cultivars: The salt-tolerant cultivar 'Xin No. 9' utilized fundamental metabolic adjustments, while the sensitive 'Xinzhen No. 9' primarily activated cell cycle-related pathways [30].

- Qi Huang No. 34: Showed enhanced regulation of phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, starch/sucrose metabolism, and ribosome pathways compared to Dong Nong No. 50 [33].

- PI 561363: Exhibited coordinated activation of suberin biosynthesis, lipid metabolism, and ABA signaling components [13].

These findings suggest that while core tolerance mechanisms are conserved, genetic background influences the relative contribution of specific pathways to the overall tolerance phenotype.

Key Candidate Genes and Molecular Switches

Ion Homeostasis Regulators

Several key genes involved in ionic homeostasis consistently emerged across studies:

- GmSALT3/GmCHX1: A major salt tolerance gene encoding a cation/H+ antiporter that reduces Na+ accumulation in shoots by preventing xylem loading [13] [31].

- GmHAK5 and GmKUP6: Potassium transporters essential for maintaining K+/Na+ ratio under salinity [13].

- GmNHX1 and GmNHX2: Vacuolar Na+/H+ exchangers that compartmentalize sodium into vacuoles [31].

- GmAKT1: Potassium channel protein involved in K+ uptake under salt stress [31].

Signaling and Transcriptional Regulators

Key regulatory genes identified across multiple studies include:

- GmOST1/SnRK2.6: ABA-activated protein kinase central to stress signaling [13].

- GmERF98 and GmERF1: Ethylene-responsive factors regulating downstream stress-responsive genes [13].

- GmWRKY and GmNAC Transcription Factors: Master regulators of abiotic stress responses [33] [31].

- GmAITR: Negative regulator of salt tolerance; its CRISPR/Cas9-mediated editing enhanced salt tolerance [31].

Protective and Detoxification Proteins

- GmGSTU19: Glutathione S-transferase involved in ROS detoxification [13].

- LEA Proteins: Late embryogenesis abundant proteins protecting cellular structures under dehydration [31].

- HSPs: Heat shock proteins maintaining protein folding under stress [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Soybean Salt Stress Transcriptomics

| Reagent Category | Specific Products | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kits | Direct-zol RNA Miniprep Kit, RNeasy Plant Mini Kit | High-quality total RNA isolation from soybean tissues [13] [34] |

| RNA Quality Control | Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer, ND-1000 Spectrophotometer | Assessment of RNA integrity, purity, and quantification [13] |

| Library Prep Kits | Illumina-Compatible Library Preparation Kits | cDNA library construction for transcriptome sequencing [13] [33] |

| Sequencing Platforms | NovaSeq X Plus Series, Illumina HiSeq | High-throughput paired-end RNA sequencing [13] [34] |

| qRT-PCR Reagents | SYBR Green Master Mix, Gene-Specific Primers | Validation of RNA-seq results for candidate genes [35] [36] |

| Antibody-Based Assays | Western Blot, ELISA Kits | Protein-level validation of key stress-responsive genes [35] [36] |

| Physiological Assay Kits | MDA Detection Kits, POX Activity Assays | Validation of oxidative stress and antioxidant responses [13] |

| Ion Content Analysis | Flame Photometry, Ion Chromatography Systems | Measurement of Na+, K+, and Cl- accumulation [29] |

Discussion and Implications for Breeding

Conserved Molecular Signatures of Salt Tolerance

The comparative transcriptomic analyses reveal that salt tolerance in soybean is governed by a core set of conserved molecular networks rather than isolated genes. The consistent identification of specific ion transporters, transcription factors, and detoxification enzymes across independent studies using different genetic backgrounds strengthens their candidacy as priority targets for molecular breeding [13] [30] [33].

Successful salt tolerance appears to depend on the precise temporal coordination of these networks, with tolerant genotypes exhibiting earlier activation of homeostatic mechanisms and more sustained regulation of protective systems. This temporal precision likely enables tolerant plants to establish cellular equilibrium before irreversible damage occurs [13] [33].

Translation to Field Applications

Promising translational successes highlight the potential of these findings for soybean improvement:

- Transgenic Approaches: Stable overexpression of ScHAL1 from Saccharomyces cerevisiae in soybean maintained high intracellular K+/low Na+ ratios under salt stress, resulting in only 8.61% yield reduction versus 34.8% in controls at 300 mM NaCl [35].

- Gene Editing: CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout of negative regulators like GmAITR has demonstrated enhanced salt tolerance [31].

- Marker-Assisted Selection: Major QTLs like GmSALT3 and GmSALT18 have been successfully deployed in breeding programs [31].

The integration of transcriptomic findings with other omics approaches (GWAS, QTL mapping) provides a powerful strategy for identifying causal genes and functional polymorphisms underlying natural variation in salt tolerance [31].

Future Research Directions

While significant progress has been made, several research gaps remain:

- Single-Cell Transcriptomics: Current bulk RNA-seq approaches mask cell-type-specific responses, particularly important for root tissues where salt perception initiates.

- Epigenetic Regulation: The role of DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNAs in salt stress memory requires further investigation [31].

- Protein-Level Validation: Transcript abundance does not always correlate with protein activity, necessitating more proteomic studies.

- Field Validation: Most transcriptomic studies employ controlled conditions; field validation under natural salinity stress is essential.

The conserved molecular networks identified in this case study provide a robust foundation for developing salt-resilient soybean varieties through integrated breeding approaches, addressing a critical challenge in global food security.

Transcription factors (TFs) are pivotal regulatory proteins that bind to specific cis-acting elements in target gene promoters, orchestrating complex transcriptional programs in response to developmental cues and environmental stresses [37]. In the realm of plant stress biology, four families—WRKY, ERF (AP2/EREBP), MYB, and bHLH—stand out for their extensive involvement in abiotic and biotic stress responses. Comparative transcriptomics of susceptible and tolerant plant varieties has revealed that the differential regulation and expression of these transcription factor families constitute a fundamental mechanism underlying stress resilience. By systematically comparing the molecular signatures of contrasting genotypes, researchers can pinpoint specific TF-mediated regulatory networks that enable tolerant varieties to withstand environmental adversities. This review synthesizes findings from comparative transcriptomic studies to objectively evaluate the performance of these four key TF families across diverse plant species and stress conditions, providing a data-driven framework for understanding their roles in plant stress adaptation.

Family Profiles and Functional Mechanisms

WRKY Transcription Factors

Structure and Classification: WRKY transcription factors contain a highly conserved WRKYGQK amino acid sequence at their N-terminus and either a C2H2 or C2HC zinc-finger motif at their C-terminus [38]. Based on their domain structure, they are classified into three major groups: Group I (two WRKY domains), Group II (one WRKY domain with C2H2 finger), and Group III (one WRKY domain with C2HC finger) [38].

Functional Mechanisms: WRKY TFs function by specifically binding to the W-box (C/TTGACC/T) cis-elements in the promoters of target genes [39]. They can act as either positive or negative regulators of the plant immune response, often mediating cross-talk between different hormone signaling pathways [39].

Table 1: WRKY Transcription Factors in Stress Response

| Plant Species | Stress Context | Key WRKY Members | Expression Pattern | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cynanchum thesioides | Cold, salt, ABA, ETH | CtWRKY9, CtWRKY18, CtWRKY19 | Significantly induced under various stresses | Positive regulation of abiotic stress response [38] |

| Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) | Ralstonia solanacearum infection | SlWRKY30, SlWRKY81 | Up-regulated in resistant line | Synergistically modulate immunity by regulating SlPR-STH2 [39] |

| Pepper (Capsicum annuum) | Ralstonia solanacearum, heat stress | CaWRKY6, CaWRKY40 | Varies by specific TF | CaWRKY40 regulates heat and bacterial wilt tolerance [39] |

ERF (AP2/EREBP) Transcription Factors

Structure and Classification: The AP2/EREBP family contains a highly conserved AP2/ERF DNA-binding domain and is divided into four subfamilies: AP2, RAV, DREB, and ERF [40]. The DREB and ERF subfamilies are particularly important for stress responses.

Functional Mechanisms: DREB subfamily proteins bind to both GCC and dehydration-responsive element (DRE) cis-elements, while ERF proteins primarily recognize the GCC box (AGCCGCC) [40]. These TFs participate in various pathways responding to drought, high salinity, diseases, and cold stress [40].

Table 2: ERF Transcription Factors in Stress Response

| Plant Species | Stress Context | Key ERF Members | Expression Pattern | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice (Oryza sativa) | Drought stress | Multiple DREB and RAV members | Up-regulated in tolerant NIL panicles under severe stress | Drought tolerance; RAV subfamily highly responsive in flowering stage [40] |

| Pineapple (Ananas comosus) | Cold stress | Multiple AP2/ERF members | Differentially expressed between tolerant and susceptible genotypes | Regulation of vernalization and hormone-mediated flowering [41] |

| Bitter gourd (Momordica charantia) | Cold stress | CBF3, ERF2, ERF17 | Up-regulated in cold-tolerant genotype | Hub genes in cold stress response network [42] |

MYB Transcription Factors

Structure and Classification: MYB TFs are characterized by their highly conserved DNA-binding domains (MYB repeats) and are classified into four categories based on the number of adjacent repeats: 1R-MYB, R2R3-MYB (the majority), R3-MYB, and R4-MYB [43].

Functional Mechanisms: MYB TFs bind to cis-acting elements such as MYBCORE, AC-box, P-box, H-box, and G-box in target gene promoters [43]. They regulate diverse processes including secondary metabolism, cell cycle control, development, and stress responses [44] [43].

Table 3: MYB Transcription Factors in Stress Response

| Plant Species | Stress Context | Key MYB Members | Expression Pattern | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ginseng (Panax ginseng) | Salt stress | PgMYB01, PgMYB71-01, PgMYB71-03, PgMYB71-05 | Up-regulated under NaCl treatment | Candidate genes for salt resistance [44] |

| Rice (Oryza sativa) | Cold, drought, UV-B stress | OsMYB2, OsTCL1, OsTCL2 | Varies by specific TF and stress | OsMYB2 associated with salt, cold and dehydration tolerance; R3-MYBs in salt and drought stress [43] |

| Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) | UV-B radiation | AtMYB4 | Down-regulated by UV-B | Enhanced UV-B tolerance when repressed [43] |

bHLH Transcription Factors

Structure and Classification: bHLH domains contain approximately 60 amino acids with two conserved regions: a basic region (involved in DNA binding) and an HLH region (mediating dimerization) [37]. Plant bHLHs are classified into multiple subfamilies, with Group B being the most predominant [37].

Functional Mechanisms: bHLH TFs recognize and bind to E-box (CANNTG) and G-box (CACGTG) elements in target gene promoters [37] [45]. They form complex regulatory networks by controlling the expression of multiple genes involved in growth, development, metabolism, and stress responses [45].

Table 4: bHLH Transcription Factors in Stress Response

| Plant Species | Stress Context | Key bHLH Members | Expression Pattern | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sophora flavescens | Abiotic stress, flavonoid biosynthesis | SfbHLH042 | Central position in interaction network | Connects bHLH genes, flavonoids, and biosynthesis enzymes [37] |

| Liriodendron chinense | Cold stress | LcICE1b | Induced by cold stress | Enhances cold tolerance via ROS scavenging [45] |

| Wheat (Triticum aestivum) | Drought, low temperature | TabHLH39 | Constitutively expressed across tissues | Enhanced drought and cold tolerance when overexpressed [37] |

| Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) | Cold stress | NtbHLH123 | Induced by cold | Enhances cold resistance by regulating CBF genes and reducing oxidative stress [37] |

Comparative Transcriptomics: Experimental Insights from Tolerant vs. Sensitive Varieties

Pineapple Cold Stress Response

Experimental Protocol: Meristem tissue was collected from precocious flowering-susceptible MD2 and precocious flowering-tolerant Dole-17 genotypes after natural cold events in field conditions. RNA sequencing was performed, followed by pairwise comparisons and weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) to identify cold stress-specific modules [41].

Key Findings: Dole-17 exhibited greater upregulation of genes conferring cold tolerance, including specific WRKY, A20, C2H2, MYB, and bZIP transcription factors. The tolerant genotype showed enhanced expression of cuticular wax biosynthesis genes, carbohydrate accumulation genes, and differential regulation of ethylene and ABA-mediated pathways compared to the susceptible MD2 [41]. Cold stress induced changes in ethylene and ABA-mediated pathways differentially between genotypes, suggesting MD2 may be more susceptible to hormone-mediated early flowering [41].

Bitter Gourd Cold Stress Adaptation

Experimental Protocol: Cold-tolerant (XY) and cold-sensitive (QF) bitter gourd genotypes were subjected to low temperature treatment. Phytohormone levels were measured by HPLC/MS, and transcriptome profiling was conducted at 0, 6, and 24 hours after treatment (HAT) using RNA-seq [42].

Key Findings: The tolerant XY genotype showed significantly increased endogenous ABA, JA, and SA contents at 24 HAT, while QF showed decreased ABA and JA [42]. More DEGs were identified at 6 HAT in sensitive QF and at 24 HAT in tolerant XY, suggesting a more delayed but sustained transcriptional response in the tolerant genotype [42]. Critical TFs including CBF3, ERF2, NAC90, WRKY51, and WRKY70 showed differential expression patterns between genotypes, with MARK1, ERF17, UGT74E2, GH3.1, and PPR identified as hub genes in the co-expression network [42].

Signaling Pathways and Regulatory Networks

The intricate signaling networks governed by the four transcription factor families can be visualized through their interconnected pathways in stress response:

Figure 1: Integrated Stress Signaling Network of Key Transcription Factor Families. This diagram illustrates the coordinated response of WRKY, ERF, MYB, and bHLH transcription factors to various environmental stresses, highlighting the central position of the ICE-CBF-COR pathway in cold response and the integration of hormone signaling across multiple TF families.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methods

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents and Experimental Solutions for Transcription Factor Studies

| Reagent/Method | Primary Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| RNA-seq & Transcriptomics | Genome-wide expression profiling | Identifying DEGs between tolerant and sensitive varieties under stress [38] [41] [42] |

| qRT-PCR | Validation and precise quantification of gene expression | Determining expression patterns of 19 CtWRKY genes in different tissues and under stresses [38] |

| Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) | Identifying correlated gene modules and hub genes | Discovering cold stress-specific modules in pineapple and hub genes in bitter gourd [41] [42] |

| MEME Suite | Discovering conserved protein motifs | Analyzing conserved motifs in MYB and WRKY transcription factors [38] [44] |

| Phylogenetic Analysis | Evolutionary relationships and classification | Classifying WRKY genes into groups I-III and MYB transcripts into 19 subclasses [38] [44] |

| STRING Database | Protein-protein interaction network prediction | Constructing interaction networks for CtWRKY proteins using Arabidopsis homologs [38] |

| HPLC/MS | Phytohormone quantification | Measuring endogenous ABA, JA, and SA contents in bitter gourd under cold stress [42] |

Comparative transcriptomic analyses of susceptible and tolerant plant varieties consistently highlight the pivotal roles of WRKY, ERF, MYB, and bHLH transcription factor families in stress resilience. Each family contributes unique regulatory capabilities while participating in interconnected networks that determine stress outcomes. The experimental data synthesized in this review demonstrates that tolerant genotypes typically exhibit more coordinated and sustained expression of stress-responsive TFs, enhanced regulation of hormone signaling pathways, and more efficient activation of downstream protective mechanisms. The continued application of comparative transcriptomics, combined with functional validation studies, will further elucidate the precise mechanisms by which these transcription factor families orchestrate stress responses, ultimately facilitating the development of stress-resistant crops through molecular breeding and biotechnological approaches.

From Data to Insights: A Practical Guide to Transcriptomic Workflows

Comparative transcriptomics of susceptible and tolerant plant varieties provides powerful insights into molecular mechanisms of stress response. This research approach relies on a foundational experimental design built on three critical pillars: appropriate plant material selection, controlled stress treatments, and robust biological replication. The core principle involves identifying genetically distinct tolerant and susceptible genotypes and subjecting them to precisely controlled stress conditions while monitoring transcriptional responses through RNA sequencing. This enables researchers to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs), key transcription factors, and enriched biological pathways that underlie stress tolerance mechanisms [46] [47] [42].

Well-designed comparative transcriptomics studies allow researchers to move beyond simple observations of phenotypic differences to understanding the molecular basis of these differences. For example, in common bean research investigating terminal drought stress, transcriptomic analysis revealed that 491 DEGs (6.4%) were upregulated in tolerant genotypes while being downregulated in sensitive genotypes, providing specific genetic targets for further investigation [46]. Similarly, studies in wheat response to Rhizoctonia cerealis identified crucial differences in phenylpropane biosynthesis pathway activation between resistant and susceptible varieties [47]. The validity of all such findings depends entirely on rigorous experimental design implemented from the initial planning stages.

Plant Material Selection Strategies

Genotype Selection Criteria

Table 1: Plant Material Selection in Recent Comparative Transcriptomics Studies

| Plant Species | Tolerant Genotype | Susceptible Genotype | Selection Basis | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) | Drought-tolerant genotypes | Drought-sensitive genotypes | Physiological screening under terminal drought | [46] |

| Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) | H83 (Moderately resistant) | 7182 (Moderately susceptible) | Field phenotyping for sheath blight resistance | [47] |

| Bitter Gourd (Momordica charantia L.) | XY (Cold-tolerant) | QF (Cold-sensitive) | Phenotypic screening under low temperature | [42] |

| Watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) | 392291-VDR (Resistant) | Crimson Sweet (Susceptible) | Germplasm screening for SqVYV resistance | [48] |

Selection of appropriate plant materials begins with identifying genetically distinct tolerant and susceptible genotypes through rigorous phenotyping. In common bean drought response studies, researchers selected three drought-tolerant and sensitive genotypes based on physiological screening under terminal drought conditions [46]. Similarly, watermelon research on squash vein yellowing virus (SqVYV) resistance used germplasm 392291-VDR, which was specifically developed and phenotyped through mechanical inoculation with SqVYV, alongside the susceptible commercial cultivar 'Crimson Sweet' [48]. The bitter gourd cold tolerance study selected genotypes XY and QF based on distinct morphological responses to cold stress, with QF showing severe wilting and chlorosis while XY maintained apparent damage resistance [42].

Genetic and Physiological Characterization

Comprehensive pre-experimental characterization ensures meaningful comparisons between genotypes. The wheat sheath blight resistance study employed cytological observations using scanning electron microscopy to confirm that hyphal growth of Rhizoctonia cerealis was more rapid on susceptible material compared to resistant genotypes [47]. In bitter gourd research, scientists measured endogenous phytohormone contents (ABA, JA, and SA) before and after stress treatment, finding significantly different hormonal responses between tolerant and sensitive lines [42]. Such characterization provides crucial baseline data for interpreting transcriptomic results and ensures that observed molecular differences correspond to established phenotypic differences.

Stress Treatment Implementation

Stress Type-Specific Treatment Protocols

Table 2: Stress Treatment Parameters in Plant Transcriptomics Studies

| Stress Type | Treatment Implementation | Duration & Intensity | Control Conditions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Terminal Drought (Common Bean) | Field-based water withholding | Progressive stress until sampling | Well-watered conditions | [46] |