Decoding Plant Cellular Diversity: Single-Cell Atlas and Gene Network Insights for Biomedical Research

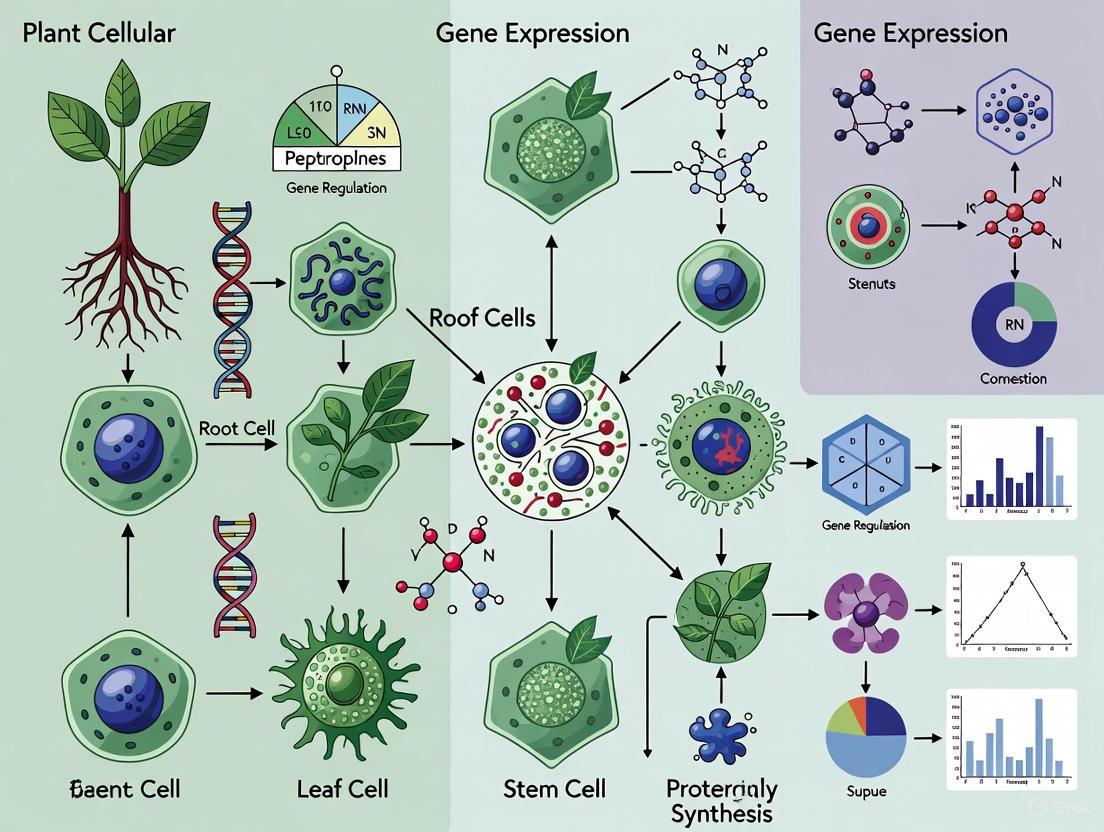

This article explores the transformative impact of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) on understanding plant cellular diversity and gene regulatory networks (GRNs).

Decoding Plant Cellular Diversity: Single-Cell Atlas and Gene Network Insights for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article explores the transformative impact of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) on understanding plant cellular diversity and gene regulatory networks (GRNs). We examine foundational atlases mapping entire plant life cycles, methodological advances in network analysis, and computational optimization techniques like Bayesian optimization. By highlighting resources like the GreenCells database and comparative studies in maize and wheat, we provide a framework for researchers to leverage plant single-cell biology. The content connects plant-specific findings to broader implications for understanding cellular heterogeneity and gene regulation in biomedical contexts, offering insights for drug development professionals exploring fundamental biological principles.

Mapping the Cellular Landscape: Comprehensive Atlases of Plant Cell Types and Developmental Trajectories

The establishment of a comprehensive, single-cell spatial transcriptomic atlas for Arabidopsis thaliana marks a transformative moment in plant biology. For decades, the small flowering weed Arabidopsis has served as the foundational model organism for plant research, enabling discoveries in light response, hormonal control, and root architecture [1] [2]. However, a technological bottleneck has historically prevented researchers from comprehensively cataloging cell types and their gene expression profiles uniformly across developmental stages [1]. This limitation has now been overcome through the integration of advanced genomic technologies.

The newly published atlas, representing the work of Salk Institute researchers, provides an unprecedented view of plant development from seed to flowering adult [1] [3]. By capturing gene expression patterns of over 400,000 cells across ten developmental stages, this resource offers the scientific community a foundational dataset that reveals the striking molecular diversity of cell types and states throughout the complete plant life cycle [4] [5]. For researchers investigating plant cellular diversity and gene expression networks, this atlas provides an invaluable reference for contextualizing specialized studies within the broader spectrum of plant development.

Technical Approaches and Methodological Innovations

Integrated Omics Technologies

The power of the Arabidopsis Life Cycle Atlas stems from its synergistic application of complementary genomic technologies. Unlike previous studies limited to specific organs or tissues, this resource employed paired single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) and spatial transcriptomics to achieve both cellular resolution and tissue context across the entire organism [3].

Single-nucleus RNA sequencing enabled the researchers to profile gene expression at the level of individual cells, identifying distinct cellular identities based on transcriptional signatures. This approach revealed 183 distinct clusters across all datasets, with median unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) of 916 per nucleus, indicating robust capture of transcriptomic information [3]. However, snRNA-seq requires tissue dissociation, which sacrifices native spatial context.

Spatial transcriptomics addressed this limitation by mapping gene activity within intact tissue structures, preserving the architectural relationships between cells and their neighbors. This technology allowed the team to validate cluster annotations and identify novel marker genes within their native tissue environments [1] [3]. The combination of these approaches facilitated confident annotation of 75% of the identified cell clusters, providing a validated framework for exploring plant cellular diversity [3] [5].

Experimental Design and Sampling Strategy

To capture the complete developmental trajectory, researchers collected samples at ten strategically chosen developmental stages representing critical transitions in the Arabidopsis life cycle [3]. The sampling framework included:

- Imbibed and germinating seeds

- Three stages of seedling development

- Developing and fully emerged rosettes

- Stem tissue

- Flowers at multiple developmental stages

- Developing siliques (seed pods) [3]

This comprehensive coverage enabled the identification of both universal transcriptional signatures conserved across recurrent cell types and organ-specific heterogeneity in gene expression patterns [3]. For each organ system, paired snRNA-seq and spatial transcriptomic datasets were generated, creating a uniquely powerful resource for hypothesis generation and validation.

Table: Experimental Sampling Strategy Across Arabidopsis Life Cycle

| Developmental Stage | Key Sampled Tissues/Organs | Primary Analysis Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Seed germination | Whole seed | snRNA-seq, Spatial transcriptomics |

| Early seedling | Hypocotyl, cotyledons | snRNA-seq, Spatial transcriptomics |

| Rosette formation | Leaves, shoot apical meristem | snRNA-seq, Spatial transcriptomics |

| Stem elongation | Stem, vascular tissue | snRNA-seq, Spatial transcriptomics |

| Flower development | Floral organs, meristems | snRNA-seq, Spatial transcriptomics |

| Silique development | Seed pods, developing seeds | snRNA-seq, Spatial transcriptomics |

Computational and Analytical Framework

Cluster annotation employed a multi-faceted approach to ensure accurate cell type identification. First, researchers compiled an extensive list of known cell-type and tissue-specific marker genes from previous studies and databases. Second, they calculated cell-type enrichment scores for each cluster based on these known markers. Third, they investigated newly identified cluster markers using previously generated dissection-based and cell-type-specific transcriptomic studies from TAIR and ePlant databases [3]. Finally, spatial validation of selected cluster markers confirmed their localization patterns within native tissue contexts.

This rigorous analytical framework allowed the team to move beyond simple cell type classification to explore cellular states—transient molecular phenotypes that reflect developmental progression, cell cycle status, or environmental responses without altering developmental potential [3]. The identification of these states provides unprecedented insight into the dynamic regulation of plant development.

Key Findings and Biological Insights

Cellular Diversity Across Development

The atlas reveals remarkable complexity in Arabidopsis cellular composition, identifying 183 distinct clusters representing specialized cell types and states [3]. Among these, 75% have been confidently annotated based on known markers and spatial validation, providing a comprehensive catalog of Arabidopsis cell types across development.

Analysis of recurrent cell types—such as epidermal and vascular cells that appear in multiple organs—revealed both conserved transcriptional signatures and organ-specific heterogeneity [3]. For example, the study identified epidermal cell markers with universal expression patterns across organs, while others showed restriction to specific contexts like seedling hypocotyls or cotyledons [3]. This nuanced understanding of cellular identity demonstrates how identical genetic programs can be modified to suit different tissue contexts.

The power of spatial transcriptomics enabled the discovery of previously uncharacterized cell-type-specific markers, including genes involved in seedpod development that had not been previously identified [1] [2]. These findings highlight how this atlas extends beyond mere cataloging to generate novel biological insights with potential applications in crop improvement and biotechnology.

Dynamic Regulatory Programs

By examining the entire life cycle rather than isolated snapshots, the researchers uncovered surprisingly dynamic transcriptional programs governing developmental transitions. The atlas captures gene expression changes associated with critical processes such as root hair development, leaf senescence, and the intricate differential growth patterns observed in structures like the apical hook of etiolated seedlings [3].

The apical hook, a transient structure that protects delicate shoot tissues during soil emergence, exemplifies the hidden complexity underlying plant morphogenesis. Spatial profiling of this structure revealed transient cellular states linked to developmental progression and hormonal regulation, providing a detailed model for understanding how localized growth patterns emerge from coordinated gene expression [3].

Functional validation experiments confirmed that genes identified through their cell-type and developmental stage-specific expression play essential roles in plant development, underscoring the predictive power of the atlas for identifying regulators of plant form and function [3] [5].

Table: Quantitative Overview of Atlas Data Resources

| Parameter | Scale/Number | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Sampled developmental stages | 10 | Covers complete life cycle from seed to senescence |

| Captured nuclei/cells | >400,000 | Represents comprehensive cellular diversity |

| Identified cell clusters | 183 | Distinct cell types and states |

| Annotated clusters | 75% (138/183) | Majority provided with confident cell type identity |

| New cell-type-specific markers validated | 109 examples | Novel gene-function relationships discovered |

Experimental Reagents and Research Toolkit

The creation of the Arabidopsis Life Cycle Atlas employed cutting-edge molecular and computational tools that can serve as a blueprint for similar efforts in other model organisms. Key reagents and methodologies include:

Genomic Technologies

Droplet-based Single-nucleus RNA Sequencing: This technology enabled high-throughput capture of transcriptomic data from individual nuclei, with median UMI counts of 916 per nucleus, ensuring robust gene expression detection [3]. The approach allowed profiling of tissues that are difficult to dissociate into intact single cells.

Sequencing-based Spatial Transcriptomics: Unlike single-cell methods that require tissue dissociation, this approach preserves the native spatial organization of cells while capturing genome-wide expression data, enabling direct correlation of transcriptional identity with tissue position [3].

Imaging-based Spatial Transcriptomics: Complementary to sequencing-based methods, these technologies provide higher spatial resolution for validating marker gene expression patterns in specific cell types within their architectural context [3].

Analytical Frameworks

Integrative Clustering Algorithms: Computational pipelines that combine data from multiple developmental stages to identify both stable cell types and transient cellular states [3].

Cell-Type Enrichment Scoring: Systematic approaches to assign cell identity based on known markers, facilitating consistent annotation across different organs and developmental stages [3].

Cross-Reference Validation: Integration with existing databases (TAIR, ePlant) and previously published cell-type-specific studies to verify cluster annotations and identify novel markers [3].

Research Applications and Future Directions

Foundational Resource for Hypothesis Generation

The Arabidopsis Life Cycle Atlas serves as a powerful foundation for exploring cellular differentiation, environmental responses, and genetic perturbations at unprecedented resolution [3] [5]. As Senior author Joseph Ecker notes, "Our study changes that. We created a foundational gene expression dataset of most cell types, tissues, and organs, across the spectrum of the Arabidopsis life cycle" [1] [2].

The atlas enables researchers to identify genes with highly specific expression patterns limited to particular cell types, developmental stages, or environmental conditions. These patterns can inform targeted functional studies using reverse genetics approaches, as demonstrated by the functional validation of genes uniquely expressed in specific cellular contexts [3].

Agricultural and Environmental Applications

Understanding the fundamental principles of plant development has direct implications for crop improvement and environmental sustainability. The dynamic transcriptional programs identified in the atlas, particularly those governing growth patterns and secondary metabolite production, provide potential targets for biotechnology approaches aimed at enhancing crop yield, stress resilience, or nutritional content [1] [2].

As co-first author Natanella Illouz-Eliaz stated, "What excites me most about this work is that we can now see things we simply couldn't see before. Imagine being able to watch where up to a thousand genes are active all at once, in the real tissue and cell context of the plant" [1] [4]. This capability opens new avenues for understanding how plants respond to environmental challenges and how these responses might be engineered for improved agricultural performance.

Integration with Complementary Approaches

The atlas is designed for integration with other data types, including genome-wide localization studies of transcription factors, epigenetic markers, and protein-protein interaction networks. Such integrative analyses promise to elucidate the complete regulatory hierarchies controlling plant development [3] [6].

The availability of this resource coincides with growing community efforts such as the Plant Cell Atlas initiative and specialized conferences like the Gordon Research Conference on Single-Cell Approaches in Plant Biology, creating synergistic opportunities for advancing plant biology through shared data and collaborative analysis [7].

Visualizing Experimental and Analytical Workflows

Atlas Construction Workflow

Atlas Data Integration and Applications

The Arabidopsis Thaliana Life Cycle Atlas represents a paradigm shift in plant biology research, providing the scientific community with an unparalleled resource for investigating plant development at cellular resolution. By integrating single-nucleus transcriptomics with spatial validation across the complete developmental continuum, this atlas reveals both the remarkable diversity of plant cell types and the dynamic regulatory programs that orchestrate their formation and function.

As a foundational dataset, it enables researchers to contextualize specialized studies within the broader framework of plant development, identify novel genes with highly specific expression patterns, and generate testable hypotheses about the regulatory networks controlling plant form and function. The publicly available nature of this resource ensures that it will serve as a cornerstone for plant biology research, with potential applications ranging from basic science to agricultural biotechnology and environmental sustainability.

For the research community investigating plant cellular diversity and gene expression networks, the atlas provides both a reference framework and an analytical toolkit for advancing our understanding of how complex multicellular organisms develop from a single fertilized egg to a mature, reproductive adult.

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Reveals Nine Distinct Cell Types in Maize Root Development

Plant development and adaptation to environmental stresses are governed by complex genetic programs that operate with cellular specificity. Unraveling this complexity requires moving beyond bulk tissue analysis to technologies that can resolve transcriptional activity at the individual cell level. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has emerged as a transformative approach for characterizing cellular heterogeneity, identifying novel cell types, and reconstructing developmental trajectories in multicellular organisms [8].

Within plant biology, maize (Zea mays) serves as both a fundamental model for basic research and a critically important crop species. Its root system represents a particularly compelling subject for scRNA-seq investigation, as roots not only provide structural anchorage but also mediate water and nutrient uptake, stress perception, and adaptive responses [9] [10]. Understanding the cellular diversity and gene regulatory networks underlying root development offers potential molecular targets for enhancing crop resilience and productivity [9].

This technical guide synthesizes recent advancements in mapping the maize root transcriptome at single-cell resolution, focusing specifically on studies that have identified nine distinct cell types during root development. We present comprehensive data on cell-type-specific markers, detailed experimental methodologies, and computational approaches for analyzing cellular trajectories and responses to environmental stimuli.

Experimental Design and Workflow

Core Experimental Protocol

The standard workflow for scRNA-seq analysis of maize roots involves several critical stages, each requiring optimization for plant tissues [10] [11]:

Plant Material and Growth Conditions: Maize seeds (typically B73 inbred line) are sterilized and germinated in the dark at a defined temperature (e.g., 28°C) for a specific duration (commonly 4 days) until roots reach approximately 4 cm in length [10]. For stress treatment studies, seedlings may be exposed to specific stressors—such as heat stress (42°C for 2 hours)—before harvesting [10].

Root Tissue Dissection and Protoplast Isolation: The apical 4 mm of root tips, encompassing the meristematic and elongation zones, is excised using a scalpel. Tissue is immediately transferred to an enzyme solution (e.g., containing cellulase, pectinase, and hemicellulase) for protoplasting. Digestion is typically performed in the dark with gentle shaking (40-50 rpm) for 2-4 hours [10] [11]. The protoplasting process is a critical step that requires careful optimization to maintain cell viability while ensuring sufficient yield.

Protoplast Purification and Quality Control: The protoplast suspension is filtered through a mesh (30-40 μm) to remove undigested tissue and debris. Protoplasts are washed and resuspended in an appropriate buffer. Cell viability, which should exceed 80%, is assessed using trypan blue staining, and concentration is adjusted to the target range (e.g., 1,000-1,200 cells/μL) for the specific scRNA-seq platform [10].

Single-Cell Library Preparation and Sequencing: The purified protoplasts are loaded onto a microfluidic device (10x Genomics Chromium Controller) to partition individual cells into droplets with barcoded beads. According to the manufacturer's protocol, single-cell RNA-seq libraries are constructed. Sequencing is performed on an Illumina platform (NovaSeq 6000 or HiSeq 4000) to a depth sufficient to confidently detect genes expressed in individual cells, with studies typically reporting median genes per cell ranging from 2,796 to 3,492 [10].

Experimental Workflow Diagram

The diagram below illustrates the complete experimental workflow for scRNA-seq analysis of maize roots, from seedling preparation to data interpretation.

Comprehensive Cell Type Identification and Characterization

The Maize Root Cell Atlas

scRNA-seq profiling of maize root tips has consistently identified nine major cell types that form the basic organizational structure of the root. These cell types can be visualized and distinguished through dimensionality reduction techniques such as UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection) and t-SNE (t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding), which group cells based on transcriptional similarity [10].

Table 1: Nine Major Cell Types Identified in Maize Root Tips via scRNA-seq

| Cell Type | Key Marker Genes | Biological Function | Developmental Zone |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epidermis | Zm00001d032822 [10] | Interface with soil environment, root hair formation | Maturation zone |

| Cortex | Zm00001d017508 [10], Zm00001d012081 (PLT2) [10] | Nutrient storage and transport, stress response | Meristematic to maturation zone |

| Endodermis | Zm00001d050168 [10] | Selective barrier for nutrient transport | Maturation zone |

| Pericycle | Zm00001d005472 [10] | Origin of lateral roots | Meristematic to elongation zone |

| Phloem | Zm00001d037032 [10] | Transport of photosynthetic products | Entire root axis |

| Xylem | Zm00001d032672 [10], Zm00001d035689 [10] | Water and mineral transport | Maturation zone |

| Stele (Vascular) | Zm00001d021192 (umc2686b) [10] | Vascular tissue formation and patterning | Meristematic zone |

| Columella | Zm00001d004089 (PRP18) [10] | Gravity sensing | Root cap |

| Meristematic | High cyclin gene expression [9] | Active cell division | Meristematic zone |

The identification of these cell types relies on the detection of cluster-specific marker genes—transcripts that show significantly higher expression in one cell population compared to all others. These markers are validated through multiple approaches, including comparison to previously established markers from other studies [10] [1], in situ hybridization [10], and spatial transcriptomic technologies that preserve the spatial context of gene expression [11].

Hormonal Regulation and Interspecies Comparisons

Analysis of cell-type-specific transcriptomes has revealed distinct expression patterns of hormone-related genes across different root cell types in maize. These patterns diverge from those observed in the model plants Arabidopsis thaliana and rice, suggesting species-specific adaptations in hormonal regulation [9]. Such comparative analyses highlight both conserved and divergent genetic programs underlying root development in monocots and dicots [12] [13].

For example, a comparative analysis of root cells between maize and rice identified 57, 216, and 80 conserved orthologous genes specifically expressed in root hair, endodermis, and phloem cells, respectively [12]. This conservation suggests fundamental genetic programs required for the formation and function of these cell types across species, while species-specific genes may underlie specialized adaptations.

Analytical Frameworks for Developmental and Stress Biology

Pseudotime Analysis of Developmental Trajectories

A powerful application of scRNA-seq data is the reconstruction of developmental trajectories using computational algorithms such as pseudotime analysis. This approach orders individual cells along a continuous path based on transcriptional similarity, inferring the progression from less differentiated to more differentiated states without requiring time-series sampling [9] [12].

In maize roots, pseudotime analysis has revealed the developmental trajectory from meristematic cortex cells to mature cortex cells, identifying candidate regulators of cell fate determination along this pathway [9]. Similarly, analysis of epidermal cells has shown that root hair cells differentiate from a subset of epidermal cells, following a continuous pseudotime series that begins with meristematic zone cells [12].

Table 2: Key Analytical Methods for scRNA-seq Data in Plant Root Studies

| Analytical Method | Application | Key Insights in Maize Roots |

|---|---|---|

| Pseudotime Analysis | Reconstructs developmental trajectories and temporal ordering of cells | Cortex and epidermis differentiation pathways; transition from meristematic to mature cells [9] [12] |

| Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) | Identifies modules of co-expressed genes and hub genes | Zm00001d021775 (STP4) identified as hub gene in mature cortex [9] |

| Differential Expression Analysis | Identifies genes with significant expression changes between conditions | Cell-type-specific heat stress responses; cortex identified as most responsive tissue [10] |

| Interspecies Comparison | Reveals conserved and divergent expression patterns | 57, 216, and 80 conserved orthologs in root hair, endodermis, and phloem of maize and rice [12] |

Cell-Type-Specific Responses to Environmental Stresses

scRNA-seq technology has enabled unprecedented resolution in studying how different root cell types respond to environmental challenges. Under heat stress (HS), maize roots show particularly pronounced transcriptional changes in the cortex, which exhibits the highest number of differentially expressed genes among all root cell types [10].

This cell-type-specific response pattern extends to other environmental factors. Research in rice has demonstrated that growth in natural soil versus homogeneous gel conditions triggers major expression changes primarily in outer root cell types (epidermis, exodermis, sclerenchyma, and cortex), with these changes involving genes related to nutrient homeostasis, cell wall integrity, and defence responses [11]. This suggests that outer root tissues serve as the first line of environmental sensing and adaptation.

Gene Co-expression Networks and Hub Gene Identification

Beyond identifying cell types, scRNA-seq data enables the construction of gene co-expression networks that reveal functional relationships between genes. Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) can identify modules of co-expressed genes that often participate in related biological processes [9] [13].

Application of WGCNA to maize root scRNA-seq data identified Zm00001d021775, which encodes a sugar transport protein (STP4), as a hub gene in the mature cortex [9]. Hub genes typically occupy central positions in co-expression networks and often play critical regulatory roles. Functional inference suggests that STP4 promotes early seedling growth by facilitating glucose transport into glycolysis and the TCA cycle [9], highlighting how network analysis can pinpoint key regulatory genes for functional validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful scRNA-seq experiments in plant roots require carefully selected reagents and materials optimized for challenging plant tissues. The following table details essential solutions used in the featured studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Plant Root scRNA-seq Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Solutions | Cellulase, Pectinase, Hemicellulase [10] [11] | Digest cell wall to release protoplasts; concentration and incubation time require optimization for different root tissues and species. |

| Protoplast Stabilizers | MgCl₂, Sorbitol, Mannitol [10] | Maintain osmotic balance and membrane integrity during and after protoplast isolation. |

| Cell Viability Assays | Trypan Blue Exclusion [10] | Assess protoplast health and integrity prior to sequencing; viability >80% typically required. |

| Single-Cell Platforms | 10x Genomics Chromium [10] | Microfluidic partitioning of individual cells with barcoded beads for library preparation. |

| Spatial Validation Tech | Molecular Cartography, Multiplexed FISH [11] | Validate cell-type markers and visualize spatial expression patterns in intact tissues. |

| Cell-Type Markers | Zm00001d017508 (Cortex) [10], Zm00001d032822 (Epidermis) [10] | Validate cell type identities through in situ hybridization or spatial transcriptomics. |

Signaling Pathways in Root Development and Stress Response

The transcriptional programs identified through scRNA-seq analysis operate within broader signaling networks that coordinate root development and stress adaptation. The diagram below integrates key signaling components and their interactions across different root cell types based on scRNA-seq findings.

This integrated view of root signaling highlights how external stimuli are perceived by specific cell types (particularly outer tissues like epidermis and cortex), leading to transcriptional changes that coordinate developmental adjustments and stress adaptation across the root system.

Single-cell RNA sequencing has fundamentally transformed our ability to dissect the cellular complexity of maize roots, providing unprecedented resolution in identifying distinct cell types, characterizing their transcriptional identities, and unraveling their developmental trajectories. The consistent identification of nine major cell types across studies establishes a foundational atlas for maize root development.

The analytical frameworks and technical protocols detailed in this guide provide researchers with essential methodologies for exploring plant development and stress responses at cellular resolution. As these technologies continue to evolve and integrate with other single-cell modalities, they will undoubtedly yield deeper insights into the genetic programs that govern cellular specialization in plants, ultimately informing strategies for enhancing crop resilience and productivity through targeted manipulation of specific root cell types and pathways.

The fundamental question of how genetically identical cells within a multicellular plant adopt distinct fates and functions lies at the heart of developmental biology. Cellular heterogeneity—the molecular diversity among individual cells—drives the specialization necessary for tissue formation, organogenesis, and environmental adaptation. Until recently, plant biologists relied primarily on bulk transcriptomic analyses that averaged gene expression across thousands to millions of cells, effectively masking the critical nuances of individual cell states. The advent of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and related spatial transcriptomic technologies has revolutionized our capacity to dissect this complexity at unprecedented resolution, enabling the identification of rare cell populations, transient states, and the precise trajectories through which cells transition during development.

This technical guide examines the integration of single-cell transcriptomics with developmental pseudotime analysis for reconstructing cell fate decisions in plants. By providing a comprehensive framework for experimental design, computational analysis, and biological interpretation, we aim to equip researchers with the methodologies needed to explore the dynamic processes of plant development at cellular resolution. Within the broader context of plant cellular diversity research, these approaches are revealing the fundamental gene regulatory networks that govern how plants build their bodies, respond to environmental challenges, and ultimately achieve their remarkable developmental plasticity.

Quantitative Landscape of Single-Cell Studies in Plants

Recent applications of single-cell technologies in plant systems have generated foundational datasets capturing diverse developmental processes and environmental responses. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from recent pioneering studies that exemplify the scale and resolution now achievable in plant single-cell research.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Findings from Recent Plant Single-Cell Studies

| Study System | Technology Used | Cell/Nuclei Number | Cell Types/States Identified | Key Biological Insight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis thaliana Life Cycle Atlas [1] [14] | Single-nucleus & Spatial Transcriptomics | ~400,000 nuclei | 183 clusters; 75% annotated | Comprehensive molecular map from seed to silique; revealed organ-specific heterogeneity |

| Maize Root Development [9] | scRNA-seq | Not specified | 9 cell types; 10 transcriptionally distinct clusters | Identified Zm00001d021775 (STP4) as hub gene for glucose transport in mature cortex |

| Arabidopsis Callus Regeneration [15] | scRNA-seq + UMAP clustering | Not specified | Multiple callus cell states | Trajectory from initiation to greening; environmental factors (O₂, light) regulate progression |

| Arabidopsis Immune Response [16] | snMultiome (RNA+ATAC) + MERFISH | 65,061 cells | 429 subclusters | Identified rare PRIMER cells and bystander cells coordinating immune responses |

| Moss 2D-to-3D Transition [17] | scRNA-seq | >17,000 cells | Major vegetative tissues | Pseudotime revealed candidate genes determining 2D tip elongation vs. 3D bud differentiation |

These datasets demonstrate how single-cell approaches are being applied across plant species and biological processes, consistently revealing greater cellular complexity than previously recognized and providing quantitative frameworks for investigating developmental trajectories.

Core Methodologies: From Tissue to Trajectory

Experimental Design and Tissue Processing

The foundation of any successful single-cell study lies in robust experimental design and tissue processing. For plant systems, this presents unique challenges due to cell walls, diverse tissue types, and secondary metabolites that can interfere with downstream applications.

Protoplast Isolation and Nuclei Extraction: Two primary approaches exist for single-cell suspension preparation: protoplast isolation and nuclei extraction. Protoplast isolation involves enzymatic digestion of cell walls using combinations of cellulases, pectinases, and hemicellulases, but can induce stress responses that alter transcriptional profiles [18]. The recently developed FX-Cell method improves protoplast preparation for challenging species and tissues [18]. Alternatively, nuclei extraction bypasses wall digestion and is particularly valuable for tissues with complex architecture or high secondary metabolite content [14]. For immune response studies, rapid nuclei isolation protocols have been developed to minimize transcriptional changes during processing [16].

Single-Cell and Single-Nucleus RNA Sequencing: The core sequencing methodologies involve capturing individual cells or nuclei in nanoliter droplets (10x Genomics) or microwells, followed by barcoded reverse transcription, library preparation, and high-throughput sequencing. The choice between scRNA-seq (capturing cytoplasmic mRNA) and snRNA-seq (capturing nuclear transcript) depends on research goals—scRNA-seq provides greater gene detection sensitivity, while snRNA-seq is less biased by transcript size and avoids digestion-induced artifacts [14].

Multiomic Integration: Advanced studies now combine snRNA-seq with additional modalities such as single-nucleus ATAC-seq (snATAC-seq) for chromatin accessibility profiling [16]. This snMultiome approach simultaneously captures both transcriptome and epigenome from the same nuclei, enabling direct correlation of transcriptional changes with regulatory element activity. When combined with spatial transcriptomics techniques like MERFISH [16] or sequencing-based spatial methods [14], this provides multidimensional data on gene expression patterns within their native tissue context.

Computational Analysis of Single-Cell Data

Quality Control and Normalization: Raw sequencing data undergoes quality assessment using tools like FastQC, followed by alignment to reference genomes (TAIR10 for Arabidopsis) [19] and unique molecular identifier (UMI) counting. Quality thresholds typically include minimum genes per cell, maximum mitochondrial transcript percentage, and removal of doublets. Normalization accounts for technical variation in sequencing depth using methods like SCTransform or variance stabilizing transformation.

Dimensionality Reduction and Clustering: Post-normalization, highly variable genes are identified for dimensionality reduction using principal component analysis (PCA). Cells are then clustered in reduced dimension space using graph-based methods (e.g., Louvain algorithm) or k-means clustering. Visualization is achieved through UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection) [15] or t-SNE plots, which project high-dimensional data into two dimensions while preserving neighborhood relationships.

Cell Type Annotation and Marker Identification: Clusters are annotated to known cell types using curated marker gene databases [14]. Differential expression analysis between clusters identifies cluster-specific markers, with statistical significance determined using methods like Wilcoxon rank-sum test or MAST. Cell-type enrichment scores can systematically infer cell identities [14]. Spatial transcriptomics validates cluster annotations by confirming expected tissue localization of marker genes [14].

Pseudotime Analysis and Trajectory Reconstruction

Algorithm Selection: Pseudotime analysis infers developmental trajectories by ordering cells along a continuum based on transcriptional similarity, reconstructing their progression through biological processes without time-series sampling. Popular algorithms include Monocle3, Slingshot, and PAGA, which employ different mathematical approaches—ranging from reversed graph embedding to minimum spanning trees—to model cell-state transitions.

Trajectory Analysis: The pseudotime trajectory is typically visualized as a branched path, with nodes representing cell states and edges indicating possible transitions. Cells are positioned along this path based on their progression through the process, with branch points indicating fate decisions. In maize root development, pseudotime analysis successfully reconstructed the developmental trajectory from early to mature cortex, revealing candidate regulators of cell fate determination [9]. Similarly, in moss, pseudotime analysis revealed larger numbers of candidate genes determining cell fates for 2D tip elongation or 3D bud differentiation [17].

Key Regulatory Network Identification: Along reconstructed trajectories, expression patterns of transcription factors and signaling components are analyzed to identify potential fate regulators. Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) [9] [19] [17] can complement pseudotime analysis by identifying modules of co-expressed genes that correlate with developmental progression. In maize roots, WGCNA identified Zm00001d021775 (sugar transport protein STP4) as a hub gene in the mature cortex [9], while similar approaches in moss identified a module connecting β-type carbonic anhydrases with auxin during the 2D-to-3D growth transition [17].

Signaling Pathways in Cell Fate Determination

The integration of single-cell transcriptomics with pseudotime analysis has elucidated key signaling pathways and regulatory networks that guide cell fate decisions in various plant developmental contexts. The following diagram illustrates the core regulatory network extracted from multiple studies:

Diagram 1: Regulatory Network Governing Plant Cell Fate Decisions

This integrated network illustrates how external and internal signals converge on transcription factors that define distinct cell states during development, regeneration, and immune responses. The spatial organization of these states, such as the PRIMER-bystander cell communication during immunity [16], emerges as a critical principle in plant tissue function.

Research Reagent Solutions for Single-Cell Plant Studies

The successful implementation of single-cell technologies requires specialized reagents and computational tools. The following table provides essential research solutions for designing and executing single-cell studies in plant systems.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Plant Single-Cell Studies

| Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Function/Application | Example Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue Dissociation | Cellulase/Pectinase Mix | Enzymatic cell wall digestion for protoplast isolation | Root tip protoplasting for scRNA-seq [9] |

| Nuclei Isolation | Sucrose Gradient Medium | Purification of intact nuclei for snRNA-seq | Rapid nuclei isolation for immune studies [16] |

| Single-Cell Platform | 10x Genomics Chromium | Partitioning cells/nuclei into droplets with barcoded beads | Arabidopsis life cycle atlas [14] |

| Spatial Transcriptomics | MERFISH/Sequencing-based | In situ mRNA localization within intact tissue | Immune cell state mapping [16] |

| Multiomic Technology | 10x Multiome (ATAC+RNA) | Simultaneous profiling of chromatin and transcriptome | Immune response regulatory logic [16] |

| Reference Genome | TAIR10/Ensembl Plants | Read alignment and gene expression quantification | Arabidopsis transcriptome analysis [19] |

| Analysis Pipeline | Seurat/Scanpy | scRNA-seq data preprocessing, normalization, and clustering | Cell type identification across development [14] |

| Trajectory Analysis | Monocle3/Slingshot | Pseudotime reconstruction and branch point analysis | Maize root development trajectory [9] |

| Network Analysis | WGCNA R Package | Co-expression network module and hub gene identification | Light signaling networks [19] |

The integration of single-cell technologies with developmental pseudotime analysis represents a paradigm shift in plant biology, transforming our understanding of cellular heterogeneity and fate decisions. These approaches have moved beyond merely cataloging cell types to actively revealing the dynamic trajectories and regulatory logic that underpin plant development, regeneration, and environmental responses. The methodologies outlined in this technical guide provide a framework for researchers to investigate these processes across diverse plant species and biological contexts.

As these technologies continue to evolve, several frontiers are emerging. The integration of single-cell proteomics, metabolomics, and epigenomics will provide multidimensional views of cell states. Spatial technologies will advance to subcellular resolution, revealing how molecular localization influences fate decisions. Computational methods will improve in predicting fate outcomes from early transcriptional states and in integrating single-cell data across species to identify conserved and divergent developmental principles. Finally, the application of these approaches to crops and non-model species will unlock new opportunities for engineering desirable traits through targeted manipulation of cell fate programs. Through continued methodological refinement and biological exploration, the dissection of cellular heterogeneity and developmental trajectories will undoubtedly yield profound insights into the fundamental principles of plant life.

Spatial transcriptomics (ST) represents a revolutionary class of technologies that integrates high-throughput transcriptomics with high-resolution tissue imaging, enabling the precise mapping of gene expression patterns within the native architectural context of tissues [20]. Unlike traditional bulk RNA sequencing, which averages gene expression across entire tissues or organs, and single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), which requires tissue dissociation and loses spatial context, ST preserves crucial spatial information while providing transcriptome-wide data [20]. This technological advancement overcomes a fundamental limitation in biological research by allowing researchers to observe where genes are expressed within intact tissue sections, providing unprecedented views of cellular heterogeneity, organization, and communication.

In plant biology, where cellular identity and function are deeply intertwined with positional context, spatial transcriptomics offers particular promise for unraveling the complex regulatory networks that govern development, environmental responses, and specialized metabolism [14] [20]. The application of ST in plant systems has lagged behind mammalian studies due to unique challenges including rigid cell walls, expansive vacuoles that dilute intracellular content, and abundant polyphenols that inhibit enzymatic reactions [20]. However, recent technological innovations are rapidly overcoming these barriers, opening new frontiers for investigating plant cellular diversity and gene expression networks within their authentic architectural contexts.

Fundamental Principles and Technological Evolution

Spatial transcriptomics technologies have evolved through three major methodological paradigms, each with distinct advantages and limitations for plant research applications.

Technology Classifications and Principles

Table: Major Spatial Transcriptomics Technological Approaches

| Technology Type | Core Principle | Resolution | Key Plant-Specific Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microdissection-Based | Laser or mechanical isolation of cells from defined spatial regions | Regional to single-cell | Compatible with cell walls; allows analysis of specific tissue domains |

| In Situ Hybridization | Hybridization of labeled probes to target transcripts | Single-molecule | Probe penetration through cell walls can be challenging |

| In Situ Capture | Spatially-barcoded oligo arrays capture mRNA from tissue sections | Single-cell to subcellular | Requires optimized tissue sectioning; compatible with various plant tissues |

| In Situ Sequencing | Amplification and sequencing of transcripts directly in tissue | Subcellular | Limited by cellular crowding; works best with thin sections |

Microdissection-Based Technologies

The earliest approaches to spatial transcriptomics relied on physical microdissection of tissue regions. Laser Capture Microdissection (LCM) pioneered this field by enabling direct cutting of target cells under microscopic guidance [20]. Subsequent refinements led to Tomo-seq, which improved quantitative accuracy and spatial resolution through enhanced cDNA library construction processes [20]. For plant applications, methods like Geo-seq combine LCM with single-cell RNA-seq to resolve transcriptomes in specific regions at subcellular-level resolution [20]. These approaches remain valuable for plant studies because they bypass cell wall-related limitations and allow precise analysis of histologically defined tissue domains.

In Situ Hybridization Technologies

In situ hybridization (ISH) technologies have progressed from rudimentary chromogenic assays to highly multiplexed fluorescent platforms that enable precise spatial mapping of nucleic acids within intact tissues [20]. Sequential Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (seqFISH) uses repeated hybridization-imaging-stripping cycles with binary encoding to dramatically expand the number of detectable transcripts [20]. Multiplexed Error-Robust Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (MERFISH) further enhanced this approach by incorporating error-robust codes and combinatorial labeling to improve accuracy and speed [20]. These technologies offer single-molecule resolution but face challenges in plant tissues due to limited probe penetration through cell walls.

In Situ Capture Technologies

In situ capture methods represent the most widely adopted ST platforms today. Technologies like 10× Genomics Visium utilize spatially barcoded oligo arrays that capture mRNA from tissue sections mounted on specialized slides [20]. By encoding positional barcodes and unique molecular identifiers, these methods provide absolute transcript counts instead of pseudo-temporal inferences alone [20]. The primary advantage for plant researchers is the ability to work with entire tissue sections without requiring specialized probes for each target, though optimization of plant tissue preparation remains essential for success.

Experimental Workflow for Plant Spatial Transcriptomics

Figure: Complete Spatial Transcriptomics Workflow for Plant Tissues

The experimental pipeline for plant spatial transcriptomics requires careful optimization at each step to address plant-specific challenges. Tissue preparation begins with selection of appropriate plant material at the desired developmental stage, followed by rapid preservation to maintain RNA integrity and spatial context [20]. For most ST platforms, optimal cryosectioning parameters must be established to overcome the challenges posed by rigid plant cell walls and varying tissue densities [20]. The permeabilization step is particularly critical in plant tissues, as cell walls present a formidable barrier to enzyme penetration; optimization requires balancing sufficient permeability for cDNA synthesis with preservation of tissue morphology [20]. Following library preparation and sequencing, the computational pipeline involves spatial alignment of sequencing data with tissue morphology images, followed by specialized analysis tools designed to extract biologically meaningful patterns from the spatial expression data [21].

Application in Plant Biology: The Arabidopsis Life Cycle Atlas

A landmark application of spatial transcriptomics in plant research is the comprehensive atlas of the Arabidopsis thaliana life cycle recently published by Salk Institute researchers [1] [14]. This resource exemplifies how ST technologies can transform our understanding of plant development and cellular differentiation.

Experimental Design and Methodological Approach

The Arabidopsis atlas was constructed using paired single-nucleus and spatial transcriptomic datasets spanning ten developmental stages, from imbibed seeds through developing siliques [14]. The researchers profiled over 400,000 nuclei from all organ systems and tissues, creating a comprehensive view of transcriptional dynamics across the entire plant life cycle [1] [14]. This experimental design enabled not only the characterization of cellular identities but also the investigation of developmental trajectories and transitional states.

The methodology integrated single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) with sequencing-based spatial transcriptomics to leverage the complementary strengths of both approaches [14]. While snRNA-seq provided high-resolution characterization of individual cellular transcriptomes, spatial transcriptomics anchored these findings within the native tissue architecture, allowing validation of putative marker genes and investigation of spatial relationships between cell types [14]. This integrated approach was essential for confident annotation of 75% of the identified cell clusters and revealed striking molecular diversity in cell types and states across development [14].

Key Findings and Biological Insights

The Arabidopsis life cycle atlas yielded several fundamental insights into plant biology:

Identification of Novel Cell-Type Markers: The study identified and spatially validated 109 new cell-type and tissue-specific marker genes across all organs, greatly expanding the molecular toolkit for studying plant cell identity [14]. These markers included genes with previously unknown functions that exhibited highly specific expression patterns.

Discovery of Context-Dependent Cellular Identities: The research demonstrated that some molecular markers do not universally specify cell types but rather exhibit cell-type-specific expression only within specific organ contexts [14]. This finding challenges simplistic definitions of cell identity and highlights the importance of spatial and developmental context in determining cellular function.

Characterization of Developmental Transitions: By profiling multiple timepoints, the atlas captured dynamic transcriptional programs governing developmental processes such as secondary metabolite production and differential growth patterns [14]. For example, detailed spatial profiling of the apical hook structure revealed transient cellular states linked to developmental progression and hormonal regulation.

Validation of Predictive Power: Functional validation of genes uniquely expressed within specific cellular contexts confirmed essential developmental roles, underscoring how spatial transcriptomics data can generate testable hypotheses about gene function [14].

Table: Key Quantitative Findings from the Arabidopsis Life Cycle Atlas

| Parameter | Value | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Developmental Stages | 10 | Comprehensive coverage from seed to senescence |

| Nuclei Profiled | 400,000+ | Extensive sampling across all organ systems |

| Cell Clusters Identified | 183 | High-resolution cellular taxonomy |

| Annotated Clusters | 75% (138/183) | Majority assigned to known or novel cell types |

| New Marker Genes | 109 | Expanded molecular toolkit for cell identity |

| Spatial Validation Rate | High confidence | Robust confirmation of computational predictions |

Computational Methods for Spatial Data Analysis

The interpretation of spatial transcriptomics data requires specialized computational approaches that address the unique challenges of spatial data integration, pattern recognition, and biological interpretation.

Data Alignment and Integration Tools

A critical first step in spatial transcriptomics analysis involves aligning and integrating multiple tissue slices to reconstruct three-dimensional tissue architecture from two-dimensional sections [21]. This process is computationally challenging due to tissue heterogeneity, spatial warping, and differences in experimental protocols. Recent reviews have identified at least 24 computational tools specifically designed for ST data alignment and integration, which can be categorized into three methodological frameworks [21]:

Statistical Mapping Approaches (10 tools): These methods, including GPSA, Eggplant, and PRECAST, use statistical models to align spatial coordinates and integrate gene expression patterns across multiple slices [21]. They are particularly effective for handling technical variability and batch effects.

Image Processing & Registration Methods (4 tools): Tools like STIM, STaCker, and STalign apply computer vision techniques to align tissue sections based on morphological features, enabling integration of ST data with histological images [21].

Graph-Based Approaches (10 tools): Methods including SpatiAlign, STAligner, and Graspot represent tissue structure as graphs and use graph-matching algorithms to align spatial datasets [21]. These approaches effectively capture cellular neighborhood relationships.

Specialized Tools for Subcellular Spatial Patterns

For high-resolution spatial transcriptomics data reaching subcellular resolution, specialized computational tools have been developed to identify and interpret functionally relevant spatial patterns of transcript distribution:

CellSP is a recently developed computational framework that enables module discovery and visualization for subcellular spatial transcriptomics data [22]. This tool introduces the concept of "gene-cell modules" - sets of genes with coordinated subcellular transcript distributions across many cells [22]. The CellSP workflow involves three key steps:

Subcellular Pattern Discovery: Using statistical tools (SPRAWL and InSTAnT) to identify four types of subcellular patterns - peripheral, radial, punctate, and central - describing transcript distributions within individual cells [22].

Module Discovery: Applying a biclustering algorithm called LAS (Large Average Submatrices) to identify gene sets that exhibit the same type of subcellular pattern in the same set of cells [22].

Module Characterization: Employing Gene Ontology enrichment tests and machine learning classifiers to biologically interpret the discovered modules and characterize their functional significance [22].

This approach has proven effective for identifying functionally significant modules across diverse tissues, including those related to myelination, axonogenesis, and synapse formation in mouse brain studies [22]. The same principles are readily applicable to plant systems for investigating processes such as cell wall formation, vascular development, and trichome differentiation.

Research Reagent Solutions for Spatial Transcriptomics

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Plant Spatial Transcriptomics

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Plant-Specific Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 10× Genomics Visium | Spatial barcoding and capture | Requires optimization of plant tissue section thickness and permeabilization |

| MERFISH Probes | Multiplexed error-robust fluorescence in situ hybridization | Probe design must account for plant-specific transcripts; cell wall penetration enhancers may be needed |

| Cryopreservation Media | Tissue preservation for cryosectioning | Formulations optimized for plant cells with rigid walls and high water content |

| Cell Wall Digesting Enzymes | Enhanced probe penetration | Controlled partial digestion to preserve morphology while improving accessibility |

| Spatial Barcode Primers | cDNA synthesis with spatial information | Must be compatible with plant mRNA features (e.g., different polyadenylation patterns) |

| Nuclear Isolation Buffers | Single-nucleus RNA sequencing | Effective isolation of intact nuclei from plant tissues with diverse secondary metabolites |

Future Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

Spatial transcriptomics technologies are rapidly evolving toward higher resolution, increased multiplexing capacity, and improved integration with other omics modalities. For plant biology, several exciting directions are emerging:

Integration with Single-Cell Epigenomics: Combining spatial transcriptomics with techniques like spatial ATAC-seq will provide insights into the regulatory landscape that underlies spatial patterns of gene expression in plant tissues.

Dynamic Spatial Mapping: Current approaches provide static snapshots, but future methodological advances may enable monitoring of spatial gene expression dynamics in living plant tissues, revealing how patterns change in response to environmental stimuli.

Multi-Species Comparative Studies: Applying spatial transcriptomics across diverse plant species will uncover conserved and divergent principles of spatial organization in plant development and evolution.

Crop Improvement Applications: Leveraging spatial transcriptomics to understand the cellular basis of agronomic traits offers promising avenues for targeted crop improvement strategies.

The integration of spatial transcriptomics into plant biology represents a paradigm shift in how researchers investigate cellular diversity and gene expression networks. By preserving the architectural context that is fundamental to plant development and function, these technologies provide unprecedented insights into the spatial regulation of biological processes. The ongoing development of both experimental and computational methods will further enhance our ability to decipher the complex spatial organization of plant tissues and its relationship to gene regulatory networks, ultimately advancing both basic plant science and agricultural applications.

Long Non-Coding RNAs (lncRNAs) as Emerging Regulators of Cellular Identity

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), defined as RNA transcripts exceeding 200 nucleotides that lack protein-coding potential, have emerged as pivotal regulators of gene expression and cellular identity in plants. Once considered genomic "dark matter," lncRNAs are now recognized for their crucial roles in directing developmental programs, enabling environmental adaptation, and defining cell-specific functions through sophisticated molecular mechanisms. These mechanisms include guiding chromatin-modifying complexes, acting as decoys for transcription factors and microRNAs, and scaffolding higher-order nuclear structures. This whitepaper synthesizes current understanding of plant lncRNA biogenesis, classification, and diverse regulatory functions, with a particular emphasis on their integration into networks controlling cellular differentiation and fate. We provide a structured technical guide featuring summarized quantitative data, detailed experimental methodologies, and visualization of core concepts to equip researchers with the tools necessary to investigate these dynamic regulators of cellular identity.

The genomic landscape of complex eukaryotes is pervasively transcribed, yielding a vast repertoire of non-coding RNAs. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) represent a major class of these transcripts, distinguished by their length (>200 nucleotides) and general lack of open reading frames encoding functional proteins [23]. In plants, lncRNAs are transcribed by multiple RNA polymerases, primarily RNA Polymerase II (Pol II), but also by the plant-specific Pol IV and Pol V, which are specialized for RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM) pathways [24] [25]. The initial perception of lncRNAs as transcriptional "noise" has been overturned by functional studies demonstrating their critical involvement in fundamental biological processes, including organ development, environmental stress responses, and epigenetic regulation [26] [27].

The definition of cellular identity—the distinct molecular and functional characteristics of a specific cell type—is orchestrated by complex gene regulatory networks. LncRNAs are increasingly recognized as integral components of these networks, fine-tuning gene expression with the spatial and temporal specificity required for cell fate determination [28]. Their functions are particularly relevant in plants, which as sessile organisms, require remarkable developmental plasticity to adapt to their environment. This whitepaper explores the mechanisms by which lncRNAs govern cellular identity, providing a technical framework for their study and highlighting their potential as targets for crop improvement and biotechnology.

Classification and Genomic Origins of Plant LncRNAs

Plant lncRNAs are categorized based on their genomic context relative to nearby protein-coding genes (Figure 1). This classification provides initial clues about their potential modes of action and target genes.

Figure 1. Classification of plant long non-coding RNAs based on genomic context.

The primary categories include:

- Long Intergenic Non-Coding RNAs (lincRNAs): Transcribed from genomic intervals between protein-coding genes. They often function in trans, regulating genes on different chromosomes [24] [29].

- Natural Antisense Transcripts (NATs): Transcribed from the opposite DNA strand of a protein-coding gene and overlap it either fully or partially. They typically regulate their sense partners in cis [24] [25]. A well-characterized example is COOLAIR in Arabidopsis, which represses the flowering-time regulator FLC [25].

- Intronic lncRNAs: Derived entirely from within the introns of protein-coding genes [24].

- Sense lncRNAs: Overlap with exonic regions of a protein-coding gene on the same strand [25].

- Bidirectional lncRNAs: Transcribed from the promoter region of a protein-coding gene but in the opposite direction, with transcription start sites located less than 1 kb apart [24].

Table 1: Classification and Characteristics of Plant LncRNAs

| Category | Genomic Origin | Potential Regulatory Mode | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| lincRNA | Intergenic regions | trans regulation; scaffolding | LAIR in rice [26] |

| NAT | Antisense strand to coding gene | cis regulation; transcriptional interference | COOLAIR in Arabidopsis [25] |

| Sense lncRNA | Same strand as coding gene | Overlap with coding gene | — |

| Intronic lncRNA | Within intron of coding gene | Regulation of host gene | — |

| Bidirectional lncRNA | Divergent transcription from promoter | Regulatory crosstalk | — |

A significant portion of plant lncRNAs, particularly lincRNAs, originate from or contain sequences of transposable elements (TEs). This association suggests TEs are a driving force in the evolution of novel lncRNAs, facilitating rapid adaptation to environmental changes [26]. Furthermore, lncRNAs can be classified as polyadenylated [poly(A)+] or non-polyadenylated [poly(A)−], with the latter often having roles in stress responses and being transcribed by Pol IV and Pol V [26] [24].

Molecular Mechanisms of LncRNA Action

LncRNAs govern gene expression through diverse and sophisticated molecular mechanisms, acting as signals, decoys, guides, scaffolds, and precursors (Figure 2). Their function is often dependent on their secondary and tertiary structures, which can be highly conserved even when the primary sequence is not [27] [23].

Figure 2. Diverse molecular mechanisms of lncRNA action in plants.

LncRNAs as Guide Molecules

LncRNAs can recruit chromatin-modifying complexes to specific genomic loci, thereby altering the local chromatin state and influencing transcription. For example, the rice antisense lncRNA LAIR binds histone modification proteins OsMOF and OsWDR5, guiding them to the LRK1 gene promoter to establish active chromatin marks (H3K4me3 and H4K16ac) and upregulate its expression [26].

LncRNAs as Scaffold Molecules

LncRNAs can serve as central platforms to assemble multiple effector molecules. The Arabidopsis lncRNA APOLO functions as a scaffold that facilitates the formation of a chromatin loop at the PID gene locus, which is crucial for the dynamic regulation of lateral root development [26].

LncRNAs as Molecular Decoys

LncRNAs can act as competitive endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) or "sponges" that sequester other regulators, such as microRNAs (miRNAs). For instance, the rice lncRNA MIKKI contains a sequence that mimics the target of miRNA171, effectively trapping it. This prevents miRNA171 from repressing its target gene SCL, thereby promoting taproot growth [26]. This mechanism is also known as endogenous target mimicry (eTM).

LncRNAs as Signaling Molecules

The expression of many lncRNAs is highly specific to particular cell types, developmental stages, or environmental conditions. This precise expression allows them to serve as molecular signals that integrate information from various signaling pathways. In Arabidopsis, specific lncRNAs are differentially expressed under stress, and their promoters are bound by stress-related transcription factors like PIF4 and PIF5 [26].

LncRNAs as Precursors for Small RNAs

Some lncRNAs are processed to generate small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), microRNAs (miRNAs), or other small RNAs. This is particularly common for lncRNAs transcribed by Pol IV, which are processed by RDR2 and DCL3 into 24-nt siRNAs that guide RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM) and transcriptional gene silencing [24] [25].

Table 2: Functional Archetypes of Plant LncRNAs with Molecular Examples

| Functional Archetype | Molecular Mechanism | Example LncRNA | Biological Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Guide | Recruits chromatin modifiers to specific DNA sequences | LAIR (Rice) [26] | Upregulates LRK1 gene expression |

| Scaffold | Nucleates assembly of multi-protein complexes | APOLO (Arabidopsis) [26] | Regulates chromatin loop dynamics in lateral root development |

| Decoy | Binds and sequesters miRNAs or transcription factors | MIKKI (Rice) [26] | Traps miRNA171 to promote taproot growth |

| Signal | Expression reports cellular state and integrates signals | SVALKA (Arabidopsis) [26] | Fine-tunes cold response gene CBF1 |

| Precursor | Processed into functional small RNAs | Pol IV transcripts [24] | Generates siRNAs for RNA-directed DNA methylation |

LncRNAs in Plant Development and Cellular Differentiation

LncRNAs are integral to the regulation of plant growth and developmental processes, where they help establish and maintain specific cellular identities. Their roles have been characterized in various contexts, from the vegetative-to-reproductive transition to the differentiation of specialized tissues.

Vernalization and Flowering Time

A classic example of lncRNA-mediated epigenetic regulation is the control of flowering time in Arabidopsis through vernalization (prolonged cold exposure). The antisense lncRNA COOLAIR is transcribed from the FLC locus and is induced by cold. COOLAIR facilitates the epigenetic silencing of FLC, a central floral repressor, leading to the acquisition of competence to flower [25]. Another lncRNA, COLDAIR, is also involved in the Polycomb-mediated repression of FLC [24].

Wood Formation and Secondary Growth

In woody perennial plants like poplar, lncRNAs are key regulators of secondary growth and wood formation (xylogenesis). These processes involve the coordinated differentiation of vascular cambium cells into xylem with thick secondary cell walls composed of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin.

- A study in Populus tomentosa identified 12 lncRNAs that regulate 16 genes involved in xylogenesis, including those related to cellulose and lignin synthesis and plant hormone control [26].

- The expression of lncRNAs is dynamically regulated during wood formation, with more lncRNAs differentially expressed in mature xylem than in developing xylem, suggesting a role in the later stages of cell wall maturation and programmed cell death [26].

- The lncRNA NERDL shows a high correlation in expression with its potential target gene PtoNERD, and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in this locus are significantly associated with wood formation traits [26].

Root Development

Lateral root formation is a key determinant of root system architecture. The Arabidopsis lncRNA APOLO is a key regulator of this process. APOLO functions as a guide and scaffold to directly modulate the 3D conformation of the chromatin at the PID auxin transporter gene. It also coordinates the expression of other auxin-responsive genes involved in lateral root primordium development by forming R-loops and facilitating chromatin loop formation [26].

Seed Development and Germination

Seed development and germination are complex processes tightly controlled by hormonal and epigenetic factors, with lncRNAs playing a significant role.

- LncRNAs are involved in regulating abscisic acid (ABA) and gibberellin (GA) signaling pathways, which are antagonistic regulators of seed dormancy and germination [25].

- They participate in endosperm imprinting, an epigenetic phenomenon where gene expression depends on the parent-of-origin, thereby influencing seed size and nutrient storage [25].

- Antisense lncRNAs of the seed maturation gene DELAY OF GERMINATION 1 (DOG1) have been identified, indicating their involvement in the complex regulation of this master dormancy regulator [26].

Technical Guide: Investigating Plant LncRNAs

The study of lncRNAs presents unique challenges due to their low abundance, poor sequence conservation, and complex structural and functional characteristics. A multi-omics approach is essential for their comprehensive identification and functional characterization.

Genome-Wide Identification and Analysis

The foundational step in lncRNA biology is their systematic identification from high-throughput sequencing data. This requires specialized bioinformatic pipelines that distinguish them from protein-coding RNAs.

Table 3: Key Experimental and Computational Methods for LncRNA Research

| Method Category | Specific Technique | Application in LncRNA Research |

|---|---|---|

| Transcriptome Sequencing | RNA-seq (PolyA+ and total RNA) | Genome-wide discovery of lncRNA transcripts [30] |

| Single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) | Identifies cell-type-specific lncRNA expression [28] | |

| Direct RNA-seq (Nanopore) | Detects RNA modifications and avoids sequencing bias [25] | |

| Chromatin Interaction | ChIRP-seq, CHART-seq | Maps lncRNA interactions with chromatin [30] |

| Functional Validation | CRISPR-Cas9 (knockout) | Generates loss-of-function mutants [30] |

| RNAi (knockdown) | Reduces lncRNA expression levels [30] | |

| VIGS (Virus-Induced Gene Silencing) | Rapid transient silencing in plants [30] | |

| Computational Tools | CPC2, CPAT, CNCI | Assesses protein-coding potential [30] |

| PLncDB, GREENC, CANTATAdb | Plant-specific lncRNA databases [24] |

Experimental Workflow:

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Use both polyA-enriched and ribosomal RNA-depleted total RNA libraries to capture the full complement of lncRNAs, including non-polyadenylated isoforms [24].

- De novo Transcriptome Assembly: Assemble transcripts from RNA-seq reads using tools like StringTie or Trinity.

- Coding Potential Assessment: Filter out putative protein-coding transcripts using a combination of tools such as CPC (Coding Potential Calculator), CPAT (Coding Potential Assessment Tool), and CNCI (Coding-Non-Coding Index) [30]. Comparison with known protein domain databases (e.g., Pfam) is also critical.

- Expression and Conservation Analysis: Quantify expression levels and analyze sequence conservation across related species, noting that lncRNA sequences are generally poorly conserved, though their promoter regions and secondary structures may be more constrained [27] [23].

Functional Characterization Protocols

Once identified, lncRNAs require rigorous functional validation. The following protocols outline key approaches.

Protocol 1: Functional Validation using CRISPR-Cas9

- Target Selection: Design sgRNAs targeting the promoter or transcriptional start site of the lncRNA locus to minimize disruption of overlapping or neighboring genes.

- Vector Construction: Clone sgRNAs into a plant-specific CRISPR-Cas9 binary vector.

- Plant Transformation: Transform the construct into the target plant species (e.g., via Agrobacterium-mediated transformation).

- Phenotypic Screening: Screen T0 and subsequent generations for morphological or developmental phenotypes.

- Genotyping and Validation: Confirm edits by sequencing and correlate genotype with phenotype. Analyze changes in the expression of putative target genes via RT-qPCR or RNA-seq [30].

Protocol 2: Molecular Mechanism Analysis via RNA Immunoprecipitation (RIP)

- Crosslinking: Treat plant tissues with formaldehyde to crosslink RNA-protein complexes in vivo.

- Cell Lysis and Immunoprecipitation: Lyse tissues and incubate the extract with an antibody specific to a protein of interest (e.g., a histone methyltransferase or transcription factor).

- RNA Extraction and Purification: Reverse the crosslinks and extract the co-precipitated RNA.

- cDNA Synthesis and qPCR: Convert the RNA to cDNA and perform qPCR with primers specific to the lncRNA to confirm the direct interaction [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Resources for LncRNA Research

| Reagent/Resource | Function and Application | Key Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Specific CRISPR-Cas9 Vectors | For precise knockout of lncRNA genomic loci. | Vectors with plant-specific promoters (e.g., U6, U3) for sgRNA and 35S for Cas9). |

| VIGS Vectors | For rapid, transient knockdown of lncRNA expression. | TRV-based (Tobacco Rattle Virus) vectors for gene silencing. |

| Antibodies for RIP | To immunoprecipitate RNA-protein complexes. | Antibodies against chromatin proteins (e.g., histone modifications, Pol II). |

| Strand-Specific RNA-seq Kits | To accurately map antisense and sense lncRNAs. | Kits that preserve strand orientation during cDNA library prep. |

| Plant LncRNA Databases | For sequence retrieval, annotation, and co-expression analysis. | PLncDB, GREENC, CANTATAdb, GreenCells (for single-cell data) [24] [28]. |

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite significant advances, the field of plant lncRNA biology is still maturing and faces several challenges. A primary issue is the lack of comprehensive functional annotation for the vast number of predicted lncRNAs [31]. This is compounded by the low sequence conservation of lncRNAs, which complicates the transfer of knowledge from model species to crops [23]. Furthermore, plant genomes are often large, complex, and polyploid, making high-quality genome assembly and accurate transcript annotation more difficult than in many animal systems [31].

Future progress will rely on several key developments:

- Single-Cell and Spatial Transcriptomics: These technologies will be indispensable for defining the precise, cell-type-specific expression patterns of lncRNAs and linking them to developmental transitions [25] [28].

- Advanced Interaction Mapping: Techniques to map the interactions of lncRNAs with DNA, RNA, and proteins in vivo will be crucial for elucidating their molecular mechanisms [25].

- Integration with Epigenomics: Combining lncRNA expression data with maps of chromatin modifications and 3D genome architecture will provide a systems-level view of their regulatory networks [30].

Unlocking the functions of plant lncRNAs holds immense potential for fundamental biology and applied agriculture. A deeper understanding of how these molecules control cellular identity will provide new strategies for engineering crops with enhanced resilience to environmental stress and improved yield traits.

Advanced Analytical Frameworks: From scRNA-seq Data to Gene Regulatory Networks

The study of long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) in plants has been significantly hampered by their characteristically low expression levels and high cell-type specificity. Traditional bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) techniques average gene expression across thousands of cells, effectively obscuring the expression patterns of lncRNAs that are restricted to specific, rare cell types [32] [33]. The advent of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized transcriptomics by providing the resolution necessary to investigate this previously hidden layer of transcriptional activity, enabling the discovery of lncRNAs with critical regulatory functions [34].

To bridge the gap between the power of scRNA-seq and the specific need to study plant lncRNAs, researchers have developed GreenCells, a comprehensive platform dedicated to the exploration of lncRNAs at single-cell resolution [32] [35]. This database systematically compiles and processes scRNA-seq data from a wide range of plant species and tissues, providing the plant research community with a specialized resource that moves beyond the protein-coding gene-centric focus of existing plant single-cell databases [32]. By integrating the identification of lncRNA marker genes with co-expression network analysis, GreenCells offers unprecedented insights into the potential roles of lncRNAs in establishing and maintaining cellular identity and function, thereby contributing significantly to the broader understanding of plant cellular diversity and gene expression networks [32].