Domain Architecture in Plant Genes: A Comprehensive Comparative Analysis for Evolutionary and Functional Insights

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of domain architecture in plant gene families, exploring its role in functional diversification, evolutionary adaptation, and stress response.

Domain Architecture in Plant Genes: A Comprehensive Comparative Analysis for Evolutionary and Functional Insights

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of domain architecture in plant gene families, exploring its role in functional diversification, evolutionary adaptation, and stress response. We examine foundational concepts of gene family expansion through whole-genome and tandem duplication, alongside methodological advances in genome-wide annotation and combinatorial optimization using CRISPR-Cas9. The content addresses troubleshooting challenges in functional redundancy and phenotypic prediction, while presenting validation approaches through expression profiling, genetic variation analysis, and protein interaction studies. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current genomic technologies and bioinformatics strategies to illuminate how domain architecture variations generate structural and functional diversity across plant species, with implications for biomedical research and therapeutic development.

Evolutionary Expansion and Diversification of Plant Gene Domain Architectures

Whole Genome Duplication and Gene Family Expansion in Plant Evolution

Whole-genome duplication (WGD) represents a profound mutational event that directly challenges genomic stability and meiotic fidelity, yet serves as a major driver of eukaryote evolution [1]. In plants, the prevalence of WGD events has provided a fundamental mechanism for genomic innovation, speciation, and adaptation to changing environments [2]. The resulting polyploid genomes experience immediate transformations in dominance structure, mutational input, and recombination dynamics, which collectively alter evolutionary trajectories [1]. Within these expanded genomic contexts, gene family expansions emerge as critical consequences of WGD, creating genetic complexity that enables functional diversification and ecological flexibility [3]. This application note examines the interplay between WGD and gene family expansion through the lens of comparative domain architecture analysis, providing researchers with methodological frameworks for investigating these phenomena in plant systems.

The comparative analysis of domain architecture offers crucial insights into evolutionary relationships among duplicated genes, revealing patterns of conservation, neofunctionalization, and subfunctionalization that shape plant phenotypes [2]. As genomic sequencing technologies advance, pan-genome approaches now enable comprehensive assessment of species-wide genetic diversity, overcoming limitations of single-reference genomes and illuminating the full extent of structural variations arising from duplication events [4]. This document presents integrated protocols for identifying, characterizing, and contextualizing gene family expansions in polyploid plants, with particular emphasis on domain-based classification and functional inference.

Quantitative Landscape of Duplication Mechanisms

Plant genomes expand through multiple duplication mechanisms that operate at different scales and temporal frequencies, each contributing distinct patterns to genomic architecture. Table 1 summarizes the primary duplication mechanisms, their characteristics, and evolutionary implications.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Gene Duplication Mechanisms in Plants

| Duplication Mechanism | Genomic Scale | Frequency | Key Characteristics | Evolutionary Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole-Genome Duplication (WGD) | Complete genome | Rare, episodic | Doubles all genetic material; creates entire duplicate subgenomes | Increases genetic redundancy; facilitates speciation; enables major functional reorganization [1] [2] |

| Tandem Duplication | Single genes to small segments | Continuous, frequent | Clustered arrangement of similar genes along chromosomes | Provides continuous source of genetic variation within species; allows fine-tuning of specific functions [3] |

| Segmental Duplication | Intermediate-sized segments | Intermediate | Duplication of chromosomal blocks; genes remain linked | Expands functionally related gene sets; maintains co-adapted gene complexes |

| Retroduplication | Single genes | Frequent | Reverse transcription of mRNAs; intron-less copies dispersed throughout genome | Creates decoupled regulatory contexts; enables expression neofunctionalization |

The differential impacts of these duplication mechanisms manifest in their contribution to gene family expansion. WGD events produce systemic duplications that initially affect all gene families equally, while tandem duplications target specific genomic regions and gene families [3]. Recent comparative genomics across 42 angiosperms revealed that tandem duplications occur at more than double the rate of other duplication mechanisms genome-wide, continuously supplying genetic variation that allows fine-tuning of context dependency in species interactions throughout plant evolution [3]. This quantitative framework provides essential context for designing evolutionary analyses of duplicated gene families.

Experimental Protocols for Gene Family Analysis

Identification and Classification of Gene Family Members

Purpose: To systematically identify members of expanded gene families in plant genomes and classify them based on domain architecture and phylogenetic relationships.

Materials/Reagents:

- High-quality genome assembly and annotation files

- Reference protein sequences for gene family of interest

- Domain databases (Pfam, InterPro)

- Multiple sequence alignment software (ClustalW, MAFFT)

- Phylogenetic analysis tools (IQ-TREE, RAxML)

Procedure:

- Data Acquisition and Preparation

Homology-Based Identification

- Perform BlastP searches using known reference sequences (E-value < 1×10⁻¹⁰, amino acid identity > 60%) [2]

- Conduct hidden Markov model (HMM) searches against protein datasets using PFAM domain profiles (e.g., PF03330, PF01357 for expansins) [5]

- Merge candidate genes from both approaches and remove duplicates

Domain Architecture Analysis

Phylogenetic Classification

- Perform multiple sequence alignment using ClustalW with BLOSUM62 matrix, gap opening penalty of 10, and extension penalty of 0.05 [2]

- Construct phylogenetic trees via neighbor-joining method with 1000 bootstrap replicates

- Classify genes into subfamilies based on phylogenetic clustering and domain composition

Validation:

- Confirm domain presence using PFAM and CDD databases

- Calculate conservation scores through multiple sequence alignment of homologous genes

- Apply length filters to exclude partial sequences (<90% or >110% of reference length) [2]

Pan-Genome Construction for Structural Variation Analysis

Purpose: To create a species-wide genomic resource that captures structural variations and presence-absence variations in diverse accessions, enabling comprehensive analysis of gene family expansions.

Materials/Reagents:

- Multiple genome assemblies from genetically diverse accessions

- Long-read sequencing data (Oxford Nanopore, PacBio)

- Graph-based genome construction tools (minigraph, pggb)

- Structural variant callers (Sniffles2, SURVIVOR)

Procedure:

- Sample Selection Criteria

- Select individuals representing >95% of species genetic diversity [4]

- Include both wild and cultivated accessions to capture domestication-related variations

- Ensure broad geographical representation covering native range

Sequence-Based Pan-Genome Construction

- Assemble individual genomes using long-read technologies (minimum 50x coverage)

- Identify structural variants (SVs) using Sniffles2 with parameters optimized for polyploids [1]

- Construct graph-based pan-genome using minigraph or similar tools

- Annotate core (shared) and accessory (variable) genomic regions

Variation Analysis

- Classify SVs into categories: deletions, insertions, inversions, duplications

- Calculate pan-genome size and trajectory (open vs. closed)

- Identify presence-absence variations (PAVs) affecting gene content

- Associate SVs with gene family expansions using synteny analysis

Functional Annotation

- Annotate variable genes using domain-based approaches

- Identify enrichment of specific gene families in accessory genome

- Correlate structural variations with phenotypic data when available

Validation:

- Simulate SV detection power using synthetic datasets [1]

- Validate SVs using orthogonal methods (PCR, optical mapping)

- Assess assembly quality using BUSCO completeness scores

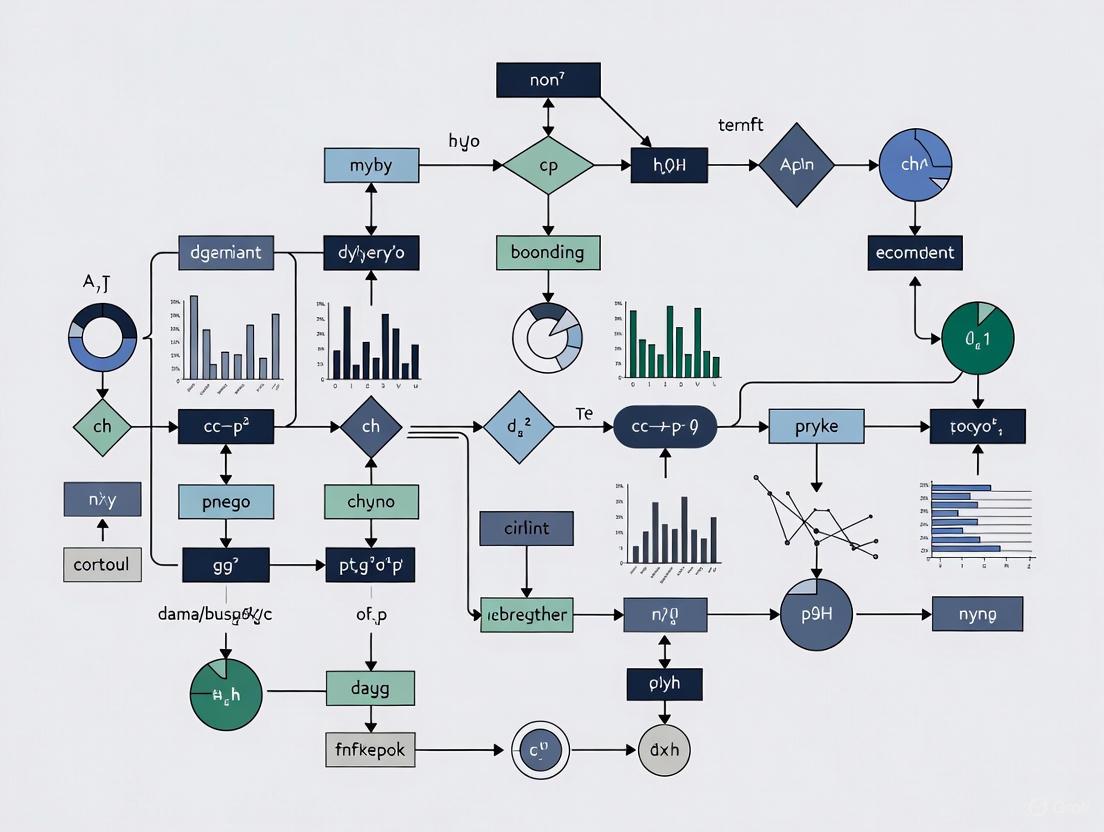

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for pan-genome construction and analysis of gene family expansions, showing key steps from sample selection to final analysis.

Analytical Framework for Evolutionary Inference

Comparative Genomics of Duplication Patterns

Purpose: To determine evolutionary mechanisms driving gene family expansions and assess functional diversification through comparative analysis across multiple species.

Materials/Reagents:

- Genomic data from multiple related species

- MCscanX software for synteny analysis

- Coding sequences and protein sequences

- Selection analysis tools (PAML, HYPHY)

Procedure:

- Synteny and Collinearity Analysis

- Perform all-versus-all BlastP searches (E-value < 1.0×10⁻⁵, max target sequences = 2) [2]

- Identify syntenic blocks using MCscanX with default parameters

- Classify genes by duplication mode: single, dispersed, proximal, tandem, WGD

- Calculate collinearity between diploid and polyploid genomes

Selection Pressure Analysis

- Calculate non-synonymous (dN) and synonymous (dS) substitution rates

- Identify signatures of positive selection (dN/dS > 1) and purifying selection (dN/dS < 1)

- Test for branch-specific and site-specific selection patterns

Functional Diversification Assessment

- Analyze similarity networks to detect functional divergence [2]

- Compare expression patterns across tissues and conditions

- Assess domain architecture variation among paralogs

Validation:

- Confirm syntenic relationships using multiple alignment methods

- Validate selection analyses using likelihood ratio tests

- Corroborate functional inferences with experimental data when available

Domain Architecture Conservation Analysis

The conservation of domain architecture across duplicated genes provides critical insights into evolutionary constraints and functional specialization. Table 2 presents quantitative metrics for assessing domain conservation in expanded gene families.

Table 2: Domain Architecture Conservation in Expanded Gene Families

| Gene Family | Representative Species | Total Genes Identified | Conserved Domain Architectures | Subfamilies Classified | Primary Expansion Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expansins [5] | Yam (Dioscorea opposita) | 30 | DPBB1 + ExpansinC (100%) | 4 (EXPA, EXPB, EXLA, EXLB) | Segmental duplication |

| Flowering-time genes [2] | 19 species across Brassicaceae, Malvaceae, Solanaceae | 22,784 | Variable by subfamily | 12+ major subfamilies | WGD followed by tandem duplication |

| Mycorrhizal symbiosis genes [3] | 42 angiosperms | Family-dependent | Context-dependent conservation | Variable across lineages | Tandem duplication (2× more than genome-wide average) |

The analytical framework reveals that domain architecture remains largely conserved immediately following duplication events, with subsequent divergence occurring through subfunctionalization and neofunctionalization processes. In flowering-time genes, for example, duplicated genes retain conserved domains while evolving regulatory differences that enable functional diversification supporting plant adaptation and survival [2].

Diagram 2: Evolutionary trajectories following gene duplication, showing how domain architecture analysis informs understanding of functional outcomes.

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Gene Family Expansion Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Specifications | Application | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Genomes | Chromosome-level assembly, comprehensive annotation | Baseline for comparative genomics, variant calling | Phytozome, BRAD, NCBI [2] |

| Domain Databases | Curated domain models (e.g., PF03330, PF01357) | Identification and classification of gene family members | PFAM, InterPro [5] |

| Multiple Sequence Alignment Tools | BLOSUM62 matrix, customizable gap penalties | Phylogenetic reconstruction, conservation analysis | ClustalW, MAFFT [2] |

| Synteny Analysis Software | Handles multiple genomes, detects collinear blocks | Identification of WGD and segmental duplications | MCscanX [2] |

| Structural Variant Callers | Optimized for polyploid genomes, long-read data | Detection of CNVs and presence-absence variations | Sniffles2 [1] |

| Pan-genome Construction Tools | Graph-based, iterative assembly approaches | Capturing species-wide genetic diversity | minigraph, PanTools [4] |

Concluding Perspectives

The integrated methodological framework presented herein enables comprehensive analysis of whole genome duplication and gene family expansion through comparative domain architecture examination. These approaches reveal that WGD events create genomic contexts permissive for innovation, while subsequent tandem duplications provide continuous fine-tuning of gene functions through context-dependent expression [3]. The strategic application of pan-genome approaches overcomes historical limitations of single-reference genomes, capturing structural variations that underlie key agronomic traits and adaptive responses [4].

For research programs investigating plant evolution and domestication, these protocols provide robust tools for connecting genomic changes with phenotypic outcomes. The expanding toolkit of genomic technologies—particularly long-read sequencing and graph-based genome representation—promises to accelerate discovery of causal relationships between gene family expansions and plant fitness traits. Future applications in crop improvement will increasingly leverage these evolutionary insights to develop varieties with enhanced resilience to climate challenges and sustainable production capabilities.

Discovery of Classical and Species-Specific Domain Architecture Patterns

Within the field of plant genomics, the comparative analysis of domain architecture in plant genes provides critical insights into evolutionary adaptations, particularly in response to pathogen pressure. This research is pivotal for understanding plant immunity and engineering disease-resistant crops. A primary focus is on nucleotide-binding site (NBS) domain genes, which constitute one of the largest superfamilies of plant resistance (R) genes [6]. These genes are instrumental in initiating effector-triggered immunity (ETI), a key branch of the plant immune system [7]. Recent large-scale comparative genomic studies have successfully identified and classified a vast repertoire of these genes across diverse plant lineages, revealing both deeply conserved classical patterns and rapidly evolving species-specific structural innovations [6]. This document outlines the standard protocols for identifying these architectures and presents key findings in an accessible format for researchers and scientists engaged in plant biotechnology and drug development.

A comprehensive analysis of 34 plant species, ranging from mosses to monocots and dicots, identified 12,820 NBS-domain-containing genes [6]. These genes were classified into 168 distinct domain architecture classes, showcasing significant diversity among plant species [6]. The table below summarizes the core findings of this comparative analysis.

Table 1: Summary of NBS Domain Architecture Analysis Across Plant Species

| Analysis Category | Description | Count |

|---|---|---|

| Species Surveyed | Green algae to higher plants (Amborellaceae, Brassicaceae, Poaceae, etc.) | 34 Species |

| NBS Genes Identified | Genes containing the NB-ARC domain (PF00931) | 12,820 Genes |

| Architecture Classes | Groups of genes with similar domain patterns | 168 Classes |

| Orthogroups (OGs) | Groups of genes descended from a common ancestor | 603 OGs |

The study distinguished between two major types of architectures:

- Classical Patterns: Well-known domain combinations such as NBS, NBS-LRR, TIR-NBS, and TIR-NBS-LRR [6].

- Species-Specific Patterns: Novel and unusual structural combinations, including TIR-NBS-TIR-Cupin1-Cupin1, TIR-NBS-Prenyltransf, and Sugar_tr-NBS [6].

Furthermore, orthogroup analysis revealed both core orthogroups (e.g., OG0, OG1, OG2), which are common across many species, and unique orthogroups (e.g., OG80, OG82), which are highly specific to particular lineages and often expanded through tandem duplications [6].

Experimental Protocols for Domain Architecture Analysis

The following section details the methodologies for the genome-wide identification and evolutionary analysis of NBS-domain genes.

Protocol 1: Identification and Classification of NBS-Domain-Containing Genes

This protocol describes the computational pipeline for identifying NBS genes and classifying their domain architectures [6].

Genome Data Acquisition:

- Source: Download the latest genome assemblies for your target species from public databases such as NCBI, Phytozome, or the Plaza genome database.

- Selection: Choose species covering a broad evolutionary spectrum (e.g., from bryophytes to angiosperms) and various ploidy levels for a comprehensive analysis.

Identification of NBS Genes:

- Tool: Use the

PfamScan.plHMM search script. - Method: Scan the predicted proteomes against the Pfam-A.hmm model library.

- Parameters: Use the default e-value cutoff of 1.1e-50.

- Criterion: Retain all genes that contain the NB-ARC domain (PF00931) for subsequent analysis.

- Tool: Use the

Classification of Domain Architectures:

- Method: Analyze the domain architecture of each identified NBS gene, noting all associated domains (e.g., TIR, LRR, CC).

- Classification System: Group genes into classes based on identical domain organization patterns, following established methods [6].

Protocol 2: Evolutionary Analysis via Orthogroup Inference

This protocol is used to understand the evolutionary relationships and diversification of NBS genes across species [6].

Orthogroup Clustering:

- Tool: Use OrthoFinder v2.5.1.

- Sequence Similarity: Perform all-vs-all sequence comparisons using the DIAMOND tool.

- Clustering: Apply the MCL (Markov Cluster) algorithm to group sequences into orthogroups (OGs) based on similarity.

Phylogenetic Analysis:

- Multiple Sequence Alignment: Use MAFFT 7.0 to align protein sequences within or across orthogroups.

- Tree Construction: Build a maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree using FastTreeMP with 1000 bootstrap replicates to assess branch support.

Duplication Analysis:

- Assessment: Investigate the mechanisms of gene family expansion (e.g., Whole-Genome Duplication vs. Small-Scale Duplications like tandem duplications) by analyzing genomic context.

Protocol 3: Functional Validation via Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS)

This protocol validates the putative role of a candidate NBS gene in disease resistance [6].

Candidate Gene Selection: Select a target NBS gene (e.g., GaNBS from orthogroup OG2) from a resistant plant accession based on expression profiling.

VIGS Construct Design: Design a construct for virus-induced gene silencing that targets the mRNA of the candidate gene.

Plant Inoculation:

- Material: Use resistant cotton plants.

- Method: Infect plants with the engineered virus vector carrying the silencing construct.

Phenotypic and Molecular Analysis:

- Disease Symptoms: Monitor the silenced plants for the development of disease symptoms following pathogen challenge.

- Virus Titer Measurement: Quantify the viral load in silenced plants compared to control plants to confirm the gene's role in limiting pathogen spread.

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

The following diagrams, generated with Graphviz, illustrate the core experimental and conceptual workflows described in this document.

NBS Gene Analysis Workflow

Plant Immune Receptor Architectures

Integrated Decoy Model for Immunity

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents, tools, and databases essential for research in plant NBS gene and domain architecture analysis.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Domain Architecture Analysis

| Item Name | Type/Function | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| PfamScan.pl | Hidden Markov Model (HMM) Search Script | Identifies protein domains, including the NB-ARC domain (PF00931), in predicted proteomes [6]. |

| OrthoFinder | Computational Phylogenomics Tool | Infers orthogroups and gene evolutionary relationships from sequence data [6]. |

| VIGS Kit | Virus-Induced Gene Silencing Kit | Validates gene function by knocking down expression of target NBS genes in plants [6]. |

| Single-Cell & Spatial Transcriptomics | Genomic Profiling Technologies | Creates high-resolution atlases of gene expression across cell types and developmental stages, useful for profiling NBS gene expression [8]. |

| ANNA Database | Angiosperm NLR Atlas | A curated database containing over 90,000 NLR genes from 304 angiosperm genomes for comparative studies [6]. |

| RNA-seq Datasets | Functional Genomics Data | Used for expression profiling of NBS genes across tissues and under various biotic/abiotic stresses from databases like IPF and CottonFGD [6]. |

Nucleotide-binding site (NBS) domain genes represent one of the largest and most critical superfamilies of plant resistance (R) genes, encoding intracellular immune receptors that confer protection against diverse pathogens including fungi, bacteria, viruses, and oomycetes [6] [9]. These genes undergo remarkable diversification through evolutionary processes, creating a vast repertoire for pathogen recognition [6] [10]. Comparative genomic analyses across land plants, from early-diverging mosses to highly derived monocots and dicots, reveal complex evolutionary patterns including species-specific expansions and contractions, resulting in significant variation in NBS gene number, architecture, and organization [6] [11] [10]. Understanding these genes' structural diversity and evolutionary dynamics provides crucial insights into plant adaptation mechanisms and offers potential genetic resources for breeding disease-resistant crops [6] [12].

Comparative Genomic Analysis of NBS Domain Genes

Diversity and Distribution Across Land Plants

Table 1: NBS-Encoding Genes Identified Across Various Plant Species

| Plant Species | Family/Group | Ploidy | Total NBS Genes | Notable Features/Distribution | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 34 species (mosses to higher plants) | Various | Mixed | 12,820 total | 168 domain architecture classes identified; several novel patterns discovered | [6] |

| Gossypium hirsutum (Upland cotton) | Malvaceae | Allotetraploid | 588 | Higher proportion of CN, CNL, and N types compared to TNL | [11] |

| Gossypium barbadense (Pima cotton) | Malvaceae | Allotetraploid | 682 | Higher proportion of TNL genes; more resistant to Verticillium wilt | [11] |

| Gossypium arboreum (Desi cotton) | Malvaceae | Diploid | 246 | Larger proportion of CN, CNL, and N genes; susceptible to Verticillium wilt | [11] |

| Gossypium raimondii | Malvaceae | Diploid | 365 | Higher proportion of TNL genes; nearly immune to Verticillium wilt | [11] |

| Ipomoea batatas (Sweet potato) | Convolvulaceae | Hexaploid | 889 | CN-type and N-type more common than other types; 83.13% in clusters | [13] |

| Solanum tuberosum (Potato) | Solanaceae | Diploid | 447 | Shows "consistent expansion" evolutionary pattern | [10] |

| Solanum lycopersicum (Tomato) | Solanaceae | Diploid | 255 | Shows "first expansion and then contraction" evolutionary pattern | [10] |

| Capsicum annuum (Pepper) | Solanaceae | Diploid | 306 | Shows "shrinking" evolutionary pattern | [10] |

| Vernicia montana (Tung tree) | Euphorbiaceae | Diploid | 149 | Contains TIR domains; resistant to Fusarium wilt | [12] |

| Vernicia fordii (Tung tree) | Euphorbiaceae | Diploid | 90 | Lacks TIR domains completely; susceptible to Fusarium wilt | [12] |

NBS domain genes exhibit tremendous diversity across the plant kingdom. A comprehensive analysis of 34 plant species ranging from mosses to monocots and dicots identified 12,820 NBS-domain-containing genes, classified into 168 distinct classes based on domain architecture patterns [6]. These encompass both classical configurations (NBS, NBS-LRR, TIR-NBS, TIR-NBS-LRR) and species-specific structural patterns (TIR-NBS-TIR-Cupin1-Cupin1, TIR-NBS-Prenyltransf, Sugar_tr-NBS) [6].

The genomic distribution of NBS-encoding genes is typically non-random and uneven across chromosomes, with a strong tendency to form clusters [11] [13]. In Ipomoea species, between 76.71% and 90.37% of NBS genes occur in clusters [13], while in Solanaceae species, these genes usually cluster as tandem arrays with few existing as singletons [10]. This organization facilitates the generation of diversity through unequal crossing-over and gene conversion [14].

Classification and Domain Architecture

NBS-encoding genes are classified based on their N-terminal domains into several major types:

- TNL: Contains Toll/Interleukin-1 receptor (TIR) - NBS - LRR domains

- CNL: Contains Coiled-Coil (CC) - NBS - LRR domains

- RNL: Contains RPW8 (Resistance to Powdery Mildew 8) - NBS - LRR domains

- Other variants: Include truncated forms lacking certain domains (TN, CN, N, NL) [11] [15]

Table 2: Distribution of NBS Gene Types Across Selected Species

| Species | TNL | CNL | RNL | Other/Truncated | Key Evolutionary Pattern | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solanum tuberosum (Potato) | 22 ancestral genes inferred | 150 ancestral genes inferred | 4 ancestral genes inferred | Various | "Consistent expansion" | [10] |

| Solanum lycopersicum (Tomato) | Derived from common Solanaceae ancestors | Derived from common Solanaceae ancestors | Derived from common Solanaceae ancestors | Various | "First expansion and then contraction" | [10] |

| Capsicum annuum (Pepper) | Derived from common Solanaceae ancestors | Derived from common Solanaceae ancestors | Derived from common Solanaceae ancestors | Various | "Shrinking" | [10] |

| Gossypium arboreum | Lower proportion | Larger proportion (CN: 17.89%, CNL: 32.52%) | Relatively unchanged | N: 23.98% | Preferential inheritance in G. hirsutum | [11] |

| Gossypium raimondii | Higher proportion (∼7x G. arboreum) | Smaller proportion (CN: 10.68%, CNL: 29.32%) | Relatively unchanged | N: 16.99% | Preferential inheritance in G. barbadense | [11] |

| Vernicia montana | Present (3 TNL, 7 TN, 2 CC-TIR-N) | Present (9 CNL, 87 CN) | Not specified | 29 NBS | Resistant to Fusarium wilt | [12] |

| Vernicia fordii | Completely absent | Present (12 CNL, 37 CN) | Not specified | 41 NBS, 12 NL | Susceptible to Fusarium wilt | [12] |

Comparative analyses reveal that TNL genes show the most dramatic variation among types. In cotton, the proportion of TNL genes in G. raimondii is approximately seven times that in G. arboreum [11]. Some species like Vernicia fordii and members of the Poaceae family have completely lost TNL genes [12] [15], while others like Mimulus guttatus (a dicot) also show species-specific TNL loss [15].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Genome-Wide Identification of NBS-Encoding Genes

Protocol 1: Identification and Classification of NBS-Encoding Genes

Principle: The NB-ARC domain (Pfam: PF00931) serves as a conserved signature for identifying NBS-encoding genes through homology-based searches [6] [11] [16].

Materials and Reagents:

- High-quality genome assemblies and annotated protein sequences

- HMMER software suite (v3.1b2 or later)

- Pfam database and HMM profiles

- COILS program for detecting coiled-coil domains

- TMHMM for transmembrane domain prediction

- BLAST suite for sequence similarity searches

Procedure:

- Initial Domain Screening: Use HMMER

hmmsearchwith the NB-ARC domain (PF00931) HMM profile against all predicted protein sequences with an e-value cutoff of 1.1e-50 [6] or 1e-5 [16] to identify candidate NBS-containing genes.

Domain Architecture Analysis: Scan candidate sequences for additional domains using:

Classification: Categorize genes based on domain combinations:

- CNL: CC-NBS-LRR

- TNL: TIR-NBS-LRR

- RNL: RPW8-NBS-LRR

- Truncated forms: CN, TN, NL, N, etc. [11]

Validation: Confirm NBS domain presence using PfamScan (e-value < 1e-5) and BLASTP against SwissProt database (e-value < 1e-5) to verify similarity to known NBS proteins [16].

Recovery of Missed Genes: Map identified NBS genes back to genome using TBLASTN (e-value < 1e-5), predict missing genes using Genewise [16].

Figure 1: Workflow for genome-wide identification and classification of NBS-encoding genes.

Evolutionary and Phylogenetic Analysis

Protocol 2: Evolutionary Analysis of NBS Gene Families

Principle: Orthologous groups and phylogenetic relationships reveal evolutionary patterns including expansion, contraction, and diversification of NBS genes across species [6] [10].

Materials and Reagents:

- OrthoFinder v2.5.1 package or similar orthology inference tool

- DIAMOND or BLAST for sequence similarity searches

- MCL clustering algorithm

- MAFFT (v7.0 or later) for multiple sequence alignment

- FastTreeMP or RAxML for phylogenetic tree construction

- MEME suite for motif discovery

Procedure:

- Orthogroup Determination: Use OrthoFinder with DIAMOND for all-vs-all sequence similarity searches and MCL for clustering to identify orthogroups [6].

Multiple Sequence Alignment: Perform alignment of NBS domain sequences using MAFFT with default parameters [6] [16].

Phylogenetic Tree Construction: Build gene trees using maximum likelihood algorithm in FastTreeMP with 1000 bootstrap replicates [6].

Motif Analysis: Identify conserved motifs using MEME with the following parameters:

- Minimum width: 6 amino acids

- Maximum width: 50 amino acids

- Maximum number of motifs: 15 [10]

Evolutionary Pattern Inference: Compare phylogenetic and systematic relationships to infer ancestral gene numbers and subsequent duplication/loss events [10].

Selection Pressure Analysis: Calculate nonsynonymous (dN) and synonymous (dS) substitution rates for orthologous pairs using PAL2NAL [16].

Functional Validation Using VIGS

Protocol 3: Functional Characterization via Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS)

Principle: VIGS enables transient gene silencing to assess the function of candidate NBS genes in plant defense responses [6] [12].

Materials and Reagents:

- Target plant specimens (e.g., resistant and susceptible cultivars)

- TRV-based (Tobacco Rattle Virus) VIGS vectors

- Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101

- Appropriate antibiotics for bacterial selection

- Acetosyringone for induction

- Syringes or vacuum infiltration apparatus

- Pathogen isolates for challenge assays

Procedure:

- Vector Construction: Clone 300-500 bp fragment of target NBS gene into TRV-based VIGS vector (e.g., TRV2) [12].

Agrobacterium Preparation:

- Transform recombinant vectors into A. tumefaciens GV3101

- Culture single colonies in LB medium with appropriate antibiotics at 28°C for 24h

- Resuspend bacterial pellets in infiltration medium (10mM MgCl₂, 10mM MES, 200μM acetosyringone) to OD₆₀₀ = 1.0-1.5

- Incubate at room temperature for 3-4 hours [12]

Plant Infiltration:

- Mix TRV1 and TRV2 (with target gene fragment) cultures in 1:1 ratio

- Infiltrate into expanded leaves using syringe or vacuum infiltration

- Maintain infiltrated plants at 22°C for 24h in dark, then transfer to normal growth conditions [12]

Silencing Validation: After 2-3 weeks, confirm gene silencing using qRT-PCR with gene-specific primers.

Phenotypic Assessment: Challenge silenced plants with target pathogen and evaluate:

- Disease symptoms and severity

- Pathogen biomass (e.g., through quantitative PCR)

- Hypersensitive response and cell death [12]

Data Analysis: Compare disease progression between silenced and control plants to determine the role of target NBS gene in resistance.

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for functional validation of NBS genes using virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS).

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for NBS Gene Analysis

| Category | Specific Tool/Resource | Function/Application | Specifications/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioinformatics Tools | HMMER Suite | Domain identification and homology search | Use with Pfam HMM profiles (NB-ARC: PF00931) |

| OrthoFinder | Orthogroup inference and evolutionary analysis | v2.5.1 with DIAMOND for sequence similarity | |

| MEME Suite | Motif discovery and analysis | Maximum 15 motifs, width 6-50 amino acids | |

| COILS Program | Coiled-coil domain prediction | Threshold 0.9 with visual inspection | |

| Experimental Materials | TRV-Based VIGS Vectors | Transient gene silencing in plants | TRV1 and TRV2 vectors for bipartite system |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 | Plant transformation for VIGS | Culture in LB with antibiotics, OD₆₀₀ = 1.0-1.5 | |

| Acetosyringone | Induction of virulence genes | 200μM in infiltration medium | |

| Databases | Pfam Database | Protein domain families | NB-ARC domain (PF00931) as primary search model |

| PRGA Database | Plant resistance gene analog information | http://sol.kribb.re.kr/PRGA/ [15] | |

| Phytozome | Plant genomic resources | Source for genome sequences and annotations |

Applications and Research Implications

The comparative analysis of NBS domain genes provides crucial insights for understanding plant immunity mechanisms and their evolution. The identification of specific NBS gene types associated with disease resistance, such as the TNL genes in Gossypium raimondii and G. barbadense that confer Verticillium wilt resistance [11], or the VmNBS-LRR gene in Vernicia montana that provides Fusarium wilt resistance [12], enables marker-assisted breeding for crop improvement.

Expression profiling under various biotic and abiotic stresses reveals responsive NBS genes that may play key roles in plant defense [6] [13]. Furthermore, the discovery of miRNA-mediated regulation of NBS-LRR genes, where diverse miRNAs typically target highly duplicated NBS-LRRs [9], adds another layer to our understanding of plant immune regulation and its evolution.

The diverse evolutionary patterns observed in different plant lineages - from the "consistent expansion" in potato to "first expansion and then contraction" in tomato and "shrinking" in pepper [10] - highlight the dynamic nature of plant-pathogen co-evolution and provide frameworks for predicting durability of resistance genes in breeding programs.

Orthogroup analysis is a fundamental methodology in comparative genomics that clusters genes from multiple species into groups descended from a single gene in their last common ancestor [17]. This approach provides a critical framework for understanding gene evolution, identifying conserved functional elements, and elucidating species-specific adaptations. Within plant genomics, orthogroup analysis has enabled significant advances in tracing the evolutionary history of gene families, understanding the genetic basis of traits, and identifying key genes involved in environmental adaptation and stress responses [18] [19]. The analysis effectively distinguishes between core genes conserved across multiple species and accessory genes that are species-specific, thereby helping researchers pinpoint genetic elements underlying phenotypic diversity [18]. With the exponential growth of sequenced plant genomes, orthogroup analysis has become an indispensable tool for making sense of complex genomic data and extracting biologically meaningful patterns from thousands of genes across dozens of species.

The power of orthogroup analysis is particularly evident in plant systems given their diverse evolutionary histories, including frequent whole-genome duplication events that are prominent drivers of gene family expansion and contraction [20] [19]. Studies across various plant families including Brassicaceae, Poaceae, Fabaceae, and Solanaceae have revealed both remarkable conservation of gene content and order (synteny), as well as lineage-specific rearrangements and innovations [20]. By systematically classifying genes into orthogroups, researchers can distinguish ancestral genetic components from more recently evolved elements, facilitating investigations into the genetic basis of adaptation, specialization, and biodiversity.

Computational Tools for Orthogroup Inference

Several computational tools are available for orthogroup inference, each with different algorithmic approaches and performance characteristics. OrthoFinder has emerged as a leading tool due to its high accuracy, comprehensive phylogenetic analysis capabilities, and user-friendly implementation [21] [22] [17]. The method addresses a previously undetected gene length bias in orthogroup inference through a novel score normalization approach, resulting in significant improvements in accuracy compared to other methods [17]. According to independent benchmarks, OrthoFinder demonstrates between 8% and 33% higher accuracy than other commonly used orthogroup inference methods and has been ranked as the most accurate ortholog inference method on the Quest for Orthologs benchmark test [22] [17].

The OrthoFinder algorithm implements a sophisticated pipeline that extends beyond simple orthogroup inference to provide comprehensive phylogenetic analysis. The process involves: (a) orthogroup inference from sequence data, (b) inference of gene trees for each orthogroup, (c) analysis of these gene trees to infer the rooted species tree, (d) rooting of gene trees using the species tree, and (e) duplication-loss-coalescence analysis of rooted gene trees to identify orthologs and gene duplication events [22]. This comprehensive approach provides researchers with not only orthogroup assignments but also evolutionary context through gene and species trees.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Features in OrthoFinder Versions

| Feature | OrthoFinder (Original) | OrthoFinder 2.0+ | OrthoFinder 3.0+ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Method | Graph-based clustering with length-normalized BLAST scores | Phylogenetic orthology inference with gene trees | Phylogenetic hierarchical orthogroups (HOGs) |

| Speed | Fast | Faster with DIAMOND option | Fastest for large analyses with --assign option |

| Key Outputs | Orthogroups, orthologs | Orthogroups, orthologs, gene trees, species tree, gene duplications | Hierarchical orthogroups, rooted gene trees, species tree, gene duplications |

| Accuracy | 8-33% more accurate than other methods [17] | Equivalent or better than competing methods [22] | 12-20% more accurate than OrthoFinder 2 [21] |

Installation and Implementation

OrthoFinder can be installed through multiple approaches, with the Bioconda channel being the recommended method for most users:

The tool requires Python and certain dependencies, though the bundled version contains all necessary components. For large-scale analyses, the --assign option in OrthoFinder 3.0 enables efficient addition of new species to existing orthogroups without recomputing the entire analysis [21]. This is particularly valuable for ongoing projects where new genomes are sequenced periodically.

Orthogroup Analysis Protocol

Input Data Preparation and Quality Control

Step 1: Gather Protein Sequence Files Collect protein sequences in FASTA format for all species to be analyzed. OrthoFinder automatically recognizes files with extensions .fa, .faa, .fasta, .fas, or .pep [21]. For plant genomes, it is essential to use the most recent genome annotations available from sources such as Phytozome, NCBI, or specialized databases like the JGI MycoCosm portal for fungi [18]. Ensure that the proteome files represent a comprehensive set of protein-coding genes for each species.

Step 2: Perform Quality Assessment Evaluate the completeness and quality of each proteome using tools like BUSCO to assess whether the gene sets contain expected conserved lineage-specific genes. This step is crucial as missing genes or fragmented sequences can lead to inaccurate orthogroup assignments. Proteomes with significantly lower BUSCO scores should be investigated before proceeding with the analysis.

Step 3: Format Input Directory Organize all FASTA files in a single directory with clear, consistent naming conventions. Species names will be derived from filenames, so use informative identifiers without special characters or spaces.

Running OrthoFinder

Basic Analysis Command:

The -t parameter specifies the number of CPU threads for BLAST/DIAMOND searches, while -a controls the number of parallel inference threads [21].

Advanced Options for Large Plant Genomes:

This command uses DIAMOND for faster sequence searches [22], and specifies multiple sequence alignment (MAFFT) and tree inference (FastTree) methods for gene tree construction.

Workflow for Hierarchical Orthogroup Analysis: For the most accurate orthogroup inference according to Orthobench benchmarks [21], use the phylogenetic hierarchical orthogroups approach:

Post-Analysis Processing and Orthogroup Classification

Step 1: Orthogroup Classification After running OrthoFinder, classify orthogroups into categories based on their distribution across species:

- Core Orthogroups: Present in all or nearly all species

- Soft-core Orthogroups: Missing in only a few species

- Accessory Orthogroups: Present in a subset of species

- Species-specific Orthogroups: Found in only one species

Step 2: Functional Annotation Integration Map functional annotations to genes within orthogroups using databases such as Gene Ontology (GO), InterPro (IPR), eukaryotic orthologous groups (KOG), and KEGG pathways [18]. This enables functional enrichment analysis to identify biological processes, molecular functions, and pathways associated with different orthogroup categories.

Step 3: Evolutionary Analysis Identify gene duplication events, lineage-specific expansions, and positive selection using the gene trees and duplication events inferred by OrthoFinder. Focus particularly on orthogroups showing unusual patterns of expansion in specific lineages that may correspond to adaptive evolution.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Orthogroup Analysis

| Category | Tool/Resource | Specific Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Analysis Software | OrthoFinder [21] [22] | Phylogenetic orthology inference | Primary orthogroup identification |

| Sequence Search | DIAMOND [22] | Accelerated BLAST-compatible search | Fast sequence similarity detection |

| Multiple Sequence Alignment | MAFFT [19] | Multiple sequence alignment | Preparing alignments for gene trees |

| Tree Inference | FastTree [19] | Phylogenetic tree inference | Gene tree construction |

| Functional Annotation | InterProScan [18] | Protein domain identification | Functional characterization of orthogroups |

| Enrichment Analysis | ClusterProfiler, topGO | GO term enrichment | Functional profiling of orthogroups |

| Visualization | ggplot2 (R), Matplotlib (Python) | Data visualization | Creating publication-quality figures |

| Genome Databases | Phytozome, NCBI, EnsemblPlants | Source of genomic data | Retrieving protein sequences |

Data Interpretation and Visualization

Analyzing Orthogroup Outputs

OrthoFinder generates several key output files that form the basis for biological interpretation:

Phylogenetic Hierarchical Orthogroups (N0.tsv): This tab-separated file contains the primary orthogroup assignments, with genes organized into columns by species [21]. According to Orthobench benchmarks, these phylogenetically-informed orthogroups are 12-20% more accurate than graph-based orthogroups [21].

Orthogroup Statistics: OrthoFinder provides comprehensive statistics including orthogroup sizes, species-specific orthogroup counts, and percentages of genes assigned to orthogroups versus unassigned genes.

Gene Trees and Species Tree: Rooted gene trees for each orthogroup and the inferred rooted species tree provide evolutionary context for interpreting orthology relationships.

Gene Duplication Events: The analysis identifies all gene duplication events in the gene trees and maps them to branches in the species tree, enabling studies of genome evolution and expansion of gene families.

Visualization Approaches

Effective visualization is critical for interpreting orthogroup analysis results. The following approaches are recommended:

Orthogroup Presence/Absence Matrix: Create a heatmap showing the presence (1) or absence (0) of orthogroups across species, clustered by species relationships.

Functional Enrichment Plots: Visualize significantly enriched GO terms or pathways in core, accessory, or lineage-specific orthogroups using bar plots or dot plots.

Gene Tree-Species Tree Reconciliation: Display gene trees alongside the species tree to illustrate duplication events and lineage-specific expansions.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete orthogroup analysis process:

Orthogroup Analysis Workflow

Case Study: Orthogroup Analysis in Plant Stress Response

A recent study demonstrated the power of orthogroup analysis by identifying conserved cold-responsive transcription factors across five eudicot species [23]. Researchers identified 10,549 orthogroups and applied phylotranscriptomic analysis of cold-treated seedlings to identify 35 high-confidence conserved cold-responsive transcription factor orthogroups (CoCoFos) [23]. This analysis included well-known cold-responsive regulators like CBFs, but also identified novel candidates such as BBX29, which was experimentally validated as a negative regulator of cold tolerance in Arabidopsis [23].

Another exemplary application comes from the analysis of NBS-domain-containing resistance genes across 34 plant species, which identified 12,820 genes classified into 168 distinct domain architecture classes [19]. Orthogroup analysis revealed 603 orthogroups with both core (conserved across species) and unique (species-specific) groups showing tandem duplications [19]. Expression profiling highlighted specific orthogroups (OG2, OG6, OG15) that were upregulated in response to biotic and abiotic stresses, providing candidates for further functional characterization [19].

Applications in Plant Genomics Research

Orthogroup analysis has enabled numerous advances in plant comparative genomics through several key applications:

Gene Family Evolution Studies

Orthogroup analysis provides a systematic framework for studying the evolution of gene families across plant lineages. Research on nucleotide-binding site (NBS) domain genes, which comprise a major class of plant disease resistance genes, utilized orthogroup analysis to reveal significant diversification across land plants [19]. The study identified classical and species-specific structural patterns and traced the expansion of NBS genes through whole-genome and tandem duplication events [19].

Comparative Phylogenomics

By identifying orthologous relationships across multiple species, orthogroup analysis enables the reconstruction of ancestral gene content and the inference of gene gain and loss events along different evolutionary lineages. A study of 92 Ascomycota fungi (68 phytopathogenic and 24 non-phytopathogenic) used orthogroup analysis to categorize genes into core, group-specific, and accessory classes [18]. This revealed that approximately 20% of orthogroups were group-specific or accessory, and identified secreted proteins with signal peptides and horizontal gene transfers as significantly enriched in phytopathogen-specific orthogroups [18].

Functional Characterization

Orthogroup analysis facilitates the transfer of functional annotations from well-characterized model species to less-studied plants. The identification of conserved orthogroups containing known stress-responsive transcription factors in Arabidopsis enables researchers to identify putative functional equivalents in crop species for further experimentation and potential crop improvement.

Table 3: Orthogroup Distribution in 92 Ascomycota Genomes [18]

| Orthogroup Category | Definition | Percentage Range | Significant Functional Enrichments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Orthogroups | Present in both pathogenic and non-pathogenic genomes | ~80% of all orthogroups | Basic cellular functions, metabolism |

| Group-Specific Orthogroups | Present in multiple genomes of one group (P or NP) but not in other group | Variable across genomes | Secreted proteins, horizontal gene transfers [18] |

| Accessory Orthogroups | Unique to individual genomes | Variable across genomes | Diverse species-specific functions |

| P-specific | Pathogen-specific orthogroups | ~8-15% per genome | Infection-related functions [18] |

| NP-specific | Non-pathogen-specific orthogroups | ~5-12% per genome | Saprotrophic-related functions |

Troubleshooting and Best Practices

Common Challenges and Solutions

Challenge 1: Incomplete Proteomes Low-quality genome assemblies or incomplete annotations can result in missing genes that artificially appear as lineage-specific losses.

Solution: Use BUSCO assessments to identify proteomes with poor completeness scores and either exclude them or interpret results with caution. Consider using transcriptome data to supplement missing gene models.

Challenge 2: Paralog Discrimination Distinguishing between orthologs and recent paralogs can be challenging, particularly after recent whole-genome duplications common in plant genomes.

Solution: Use the phylogenetic hierarchical orthogroups (HOGs) generated by OrthoFinder, which provide more accurate orthology inferences than graph-based methods [21]. For specific gene families of interest, perform additional phylogenetic analysis with manual curation.

Challenge 3: Computational Resources Large-scale analyses with dozens of plant genomes can be computationally intensive.

Solution: Use the DIAMOND option for faster sequence searches [22], and consider running the analysis in stages using the --assign option in OrthoFinder 3.0 to add species incrementally [21].

Interpretation Guidelines

When interpreting orthogroup analysis results:

Consider the evolutionary context of the species included, as the inclusion of outgroup species can significantly improve orthogroup accuracy [21].

Be cautious when interpreting absence of genes from orthogroups, as this could result from biological reality (true gene loss) or technical artifacts (incomplete genomes).

Use functional enrichment analysis statistically to identify biologically meaningful patterns rather than focusing on individual genes without context.

Validate key findings with experimental approaches, as demonstrated in the cold-response study where BBX29 was functionally characterized after computational identification [23].

Orthogroup analysis represents a powerful approach for comparative genomics that continues to evolve with computational advances. The methodology provides a systematic framework for understanding gene evolution across plant species, identifying conserved and lineage-specific genetic elements, and generating hypotheses for functional studies. As plant genomics continues to expand with increasing numbers of sequenced genomes, orthogroup analysis will remain an essential tool for making sense of this wealth of data and extracting biologically meaningful insights.

Functional Diversification through Neofunctionalization and Subfunctionalization

Gene duplication is a fundamental evolutionary process that provides the raw genetic material for functional innovation. Following duplication, duplicated gene copies can undergo several evolutionary fates: nonfunctionalization, where one copy accumulates deleterious mutations and becomes a pseudogene; subfunctionalization, where the ancestral functions are partitioned between the duplicates; and neofunctionalization, where one copy acquires a novel function [24] [25]. In plants, whole-genome duplication events have been pervasive, making the study of these evolutionary trajectories particularly relevant for understanding the genetic basis of adaptation and diversification [25]. This application note provides a detailed experimental framework for investigating these processes, with a specific focus on the analysis of domain architecture in plant gene families.

Key Concepts and Definitions

- Neofunctionalization: A process in which one duplicated gene copy acquires a novel molecular or regulatory function that was not present in the ancestral gene [24] [25]. This can occur through coding sequence changes (Coding Neofunctionalization, C-NF) or through divergence in expression patterns (Regulatory Neofunctionalization, R-NF) [25].

- Subfunctionalization: A process where the original functions of the ancestral gene are subdivided between the duplicated copies, with each copy specializing in a distinct subset of the ancestral functions [24].

- Nonfunctionalization: The loss of function in one duplicated copy due to the accumulation of degenerative mutations, often resulting in a pseudogene [24].

Case Study: Functional Diversification of Soybean Phytochrome A Genes

The phytochrome A (PHYA) gene family in soybean (Glycine max) provides an exemplary model for studying functional diversification. Following whole-genome duplication events, soybean possesses four PHYA copies (GmPHYA1-GmPHYA4), each demonstrating a distinct evolutionary pathway [24] [26].

Table 1: Functional Diversification of Soybean GmPHYA Genes

| Gene Name | Evolutionary Fate | Functional Characteristics | Key Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| GmPHYA1 | Subfunctionalization | Regulates photomorphogenesis and plant height; collaborates with GmPHYA2 in far-red light signaling [24]. | Complementation of Arabidopsis phyA mutant; protein degradation assays [24]. |

| GmPHYA2 | Subfunctionalization & Neofunctionalization | Regulates flowering time under both far-red and red-enriched light conditions [24] [26]. | Complementation assays; phenotypic analysis of CRISPR mutants [24]. |

| GmPHYA3 | Neofunctionalization | Protein stable in red light; regulates flowering time under red-enriched light—a function not found in ancestral PHYA [24] [26]. | Kinetic analysis of protein degradation; phylogenetic analysis [24]. |

| GmPHYA4 | Nonfunctionalization | Lacks a key protein domain; considered a pseudogene with no functionality [24] [26]. | Domain architecture analysis; absence of function in genetic assays [24]. |

Experimental Workflow for Functional Analysis

The following diagram outlines a multi-strategy workflow for determining the evolutionary fate of duplicated genes, as applied in the soybean PHYA case study.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Phylogenetic and Structural Analysis of Duplicated Genes

Objective: To reconstruct evolutionary relationships and identify structural changes, including domain architecture, among duplicated genes.

Materials:

- Software: MEGA7/11, MEME Suite, TBtools, CD-Search, SMART database.

- Data: Protein or nucleotide sequences of the gene family of interest from relevant databases (e.g., Phytozome, NCBI).

Procedure:

- Sequence Retrieval: Collect full-length amino acid sequences for all members of the gene family from the target species and homologs from related species.

- Multiple Sequence Alignment: Perform alignment using the MUSCLE algorithm in MEGA11 with default parameters [27].

- Phylogenetic Tree Construction: Build a Maximum-Likelihood tree in MEGA11. Use 1000 bootstrap replicates to assess node support [28] [27].

- Domain and Motif Analysis:

- Visualization: Use TBtools to visualize the phylogenetic tree alongside gene structures and motif compositions.

Protocol 2: Heterologous Complementation Assay

Objective: To test the functional capacity of duplicated genes by expressing them in a model organism mutant background.

Materials:

- Biological: Model organism mutant lines (e.g., Arabidopsis thaliana phyA-211 mutant).

- Vectors: Plant transformation binary vectors (e.g., pCAMBIA series).

- Reagents: Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101, plant growth media, antibiotics, selection agents.

Procedure:

- Vector Construction: Clone the coding sequence of the target gene (e.g., GmPHYA1) into a plant expression vector under a constitutive promoter (e.g., 35S CaMV).

- Plant Transformation: Introduce the construct into Agrobacterium and transform the mutant plant line via floral dip.

- Selection and Genotyping: Select transgenic plants on antibiotic-containing media and confirm transgene integration by PCR and expression by RT-qPCR.

- Phenotypic Analysis: Grow T2 or T3 transgenic lines and relevant controls under appropriate conditions. Quantitatively assess rescue of the mutant phenotype (e.g., hypocotyl elongation under far-red light, flowering time) [24].

Protocol 3: Kinetic Analysis of Protein Degradation

Objective: To compare the biochemical stability of proteins encoded by duplicated genes, which can indicate functional divergence.

Materials:

- Cell Culture: Protoplasts isolated from plant tissue or suitable cell lines.

- Reagents: Protein synthesis inhibitors (e.g., Cycloheximide), proteasome inhibitors (e.g., MG132), antibodies for immunoblotting, light sources for photoreceptor studies.

Procedure:

- Protein Expression: Transiently express epitope-tagged versions of the target proteins in protoplasts.

- Inhibition and Sampling: Add cycloheximide to halt new protein synthesis. Collect cell samples at specific time points (e.g., 0, 1, 2, 4, 8 hours) post-inhibition.

- Protein Extraction and Detection: Lyse cells, quantify total protein, and detect the target protein via SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting using a tag-specific antibody.

- Quantification and Half-life Calculation: Measure band intensity, plot relative protein abundance over time, and calculate the half-life of each protein. Neofunctionalization may be indicated by significant differences in stability, as seen with GmPHYA3 in red light [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Gene Family Functional Studies

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| pCAMBIA Vectors | Plant transformation binary vectors for gene overexpression or silencing. | Cloning GmPHYA genes for complementation assays in Arabidopsis [24]. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | For targeted genome editing to create knockout or knock-in mutations. | Generating single and multiple GmphyA mutants in soybean to study redundancy and specific functions [24]. |

| Cycloheximide | Inhibitor of protein synthesis; used in protein degradation kinetics studies. | Determining the half-life of GmPHYA3 versus GmPHYA1/2 proteins [24]. |

| Specific Antibodies | Immunodetection of proteins of interest in Western blot, ELISA, or IP. | Detecting epitope-tagged PHYA proteins in degradation assays or assessing expression levels. |

| Phytohormones (ABA, MeJA) | Treatment compounds to study gene expression in response to abiotic stress and signaling. | Analyzing expression of stress-responsive genes like TaDOG in wheat or P5CS in tomato [28] [27]. |

Regulatory Neofunctionalization: A Genome-Wide Perspective

Beyond changes in protein function, regulatory neofunctionalization (R-NF) is a widespread phenomenon. A genome-wide study in maize revealed that 13% of retained homeolog gene pairs showed evidence of R-NF in leaves, where one copy evolved a new expression pattern [25]. The analysis further showed that R-NF genes are under strong purifying selection and that their functional annotations are consistent with the biological roles of the tissues where they are expressed [25].

Protocol 4: Identifying Regulatory Neofunctionalization using RNA-seq

Objective: To identify duplicated gene pairs that have diverged in their expression patterns (R-NF).

Materials:

- Tissues: Multiple tissue types or stress-treated samples from the study organism.

- Software: OrthoFinder (for orthogroup inference), DESeq2/EdgeR (for differential expression), R/Bioconductor.

Procedure:

- Transcriptome Data Collection: Obtain RNA-seq data from diverse tissues, developmental stages, or stress conditions.

- Read Mapping and Quantification: Map reads to the reference genome and calculate gene expression values (e.g., FPKM, TPM).

- Orthogroup Assignment: Use OrthoFinder to assign duplicated genes into orthogroups and identify retained pairs [6] [30].

- Expression Divergence Analysis:

- For each homeolog pair, perform pairwise statistical tests (e.g., Wilcoxon signed-rank test) to compare expression profiles across all samples.

- Classify pairs as R-NF if one gene shows a significantly altered expression profile in a specific tissue or condition, indicating a potential new regulatory role [25].

The integrated application of phylogenetic, genetic, biochemical, and genomic protocols outlined in this note provides a robust roadmap for elucidating the evolutionary fates of duplicated genes. The strategic analysis of domain architecture is central to this process, as domain loss or modification often underpins functional diversification. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for fundamental plant biology and has direct applications in crop improvement, enabling the targeted selection or engineering of genes that have acquired beneficial traits.

Advanced Methodologies for Domain Architecture Analysis and Engineering

Genome-Wide Identification and Re-annotation Strategies

Genome-wide identification of gene families and subsequent genomic re-annotation represent foundational processes in modern plant genomics research, enabling deeper understanding of gene function, evolution, and architecture. Domain architecture analysis provides a critical framework for comparative genomics, revealing how protein domain arrangements contribute to functional diversification and specialized biological processes, including disease resistance and stress adaptation [6] [7]. The rapid expansion of genomic data, coupled with advancements in sequencing technologies and bioinformatic tools, has transformed our ability to characterize complex gene families at unprecedented scale and resolution. These approaches are particularly valuable for studying plant immune receptors and other mechanistically important gene families where domain rearrangements and fusions create functional diversity [7].

The integration of high-quality genome re-annotation with domain-centric comparative analyses offers powerful insights into evolutionary adaptations across plant species. This application note details standardized protocols for genome-wide gene identification and re-annotation, framed within the context of comparative domain architecture research in plants, providing researchers with practical methodologies to advance studies in functional genomics, evolutionary biology, and crop improvement.

Key Concepts and Significance

Genome-Wide Identification of Gene Families

Genome-wide identification involves the comprehensive detection and characterization of all members of a specific gene family within a fully sequenced genome. This process typically begins with domain-based searches using hidden Markov models (HMMs) or sequence similarity tools to identify genes sharing conserved protein domains or motifs [6] [7]. For example, studies focusing on nucleotide-binding site (NBS) domain genes—key players in plant disease resistance—leverage Pfam domain models to systematically identify these genes across multiple plant species [6]. The resulting data enable comparative analyses of gene family expansion, contraction, and structural variation across evolutionary lineages.

Genome Re-annotation Strategies

Genome re-annotation refers to the process of improving existing genome annotations by incorporating new evidence from advanced sequencing technologies, transcriptomic data, and refined computational methods. Re-annotation addresses limitations in initial annotations that often arise from short-read sequencing technologies, which may struggle with complex repetitive regions and fail to accurately resolve gene models [31]. Successful re-annotation, as demonstrated in the reef-building coral Acropora intermedia, substantially improves assembly contiguity, resolves ambiguous bases, and increases the completeness of protein-coding gene predictions [31]. Similarly, evidence-guided re-annotation of the root-knot nematode (Meloidogyne chitwoodi) genome significantly improved BUSCO scores from 48.7% to 71%, indicating enhanced identification of conserved core orthologs [32].

Table 1: Impact of Genome Re-annotation on Assembly and Annotation Quality

| Metric | Previous Assembly | Re-annotated Assembly | Improvement | Organism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contig N50 | 40.3 Kb | 2.9 Mb | ~72-fold | Acropora intermedia [31] |

| BUSCO Completeness | 90.6% | 92.6% | +2.0% | Acropora intermedia [31] |

| Gene BUSCO | 93.0% | 95.7% | +2.7% | Acropora intermedia [31] |

| BUSCO Score | 48.7% | 71.0% | +22.3% | Meloidogyne chitwoodi [32] |

| Ambiguous Bases (per 100 Kbp) | 5,276.11 | 0 | Complete resolution | Acropora intermedia [31] |

Domain Architecture Analysis in Plant Genes

Proteins frequently comprise multiple functional domains arranged in specific architectures that determine their biological functions. Comparative analysis of domain architectures uncovers evolutionary innovations and functional specializations, particularly in plant immune receptors where non-canonical domain arrangements often mediate pathogen recognition [7]. For instance, nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat (NLR) proteins—key intracellular immune receptors in plants—exhibit remarkable architectural diversity through integration of additional domains that serve as "baits" for pathogen-derived effector proteins [7]. These integrated domains (NLR-IDs) represent evolutionary adaptations that expand the pathogen recognition capacity of the plant immune system.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol for Genome-Wide Identification of Domain-Encoding Genes

This protocol outlines a standardized pipeline for identifying genes belonging to a specific protein domain family across multiple plant genomes.

Data Collection and Preparation

- Genome Source Selection: Obtain predicted proteome files for target species from public databases (NCBI, Phytozome, Plaza) [6]. Prioritize genomes with high assembly quality and comprehensive annotation.

- Domain Reference Libraries: Download relevant Pfam Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) for domains of interest (e.g., NB-ARC/PF00931 for NLR identification) [7].

Domain Identification and Classification

- HMMER Search: Execute domain searches using

PfamScan.plHMM search script with default e-value cutoff (1.1e-50) against the Pfam-A.hmm model [6]: - Architecture Classification: Classify genes based on domain organization using established systems that group similar domain-architecture-bearing genes into the same classes [6].

Evolutionary and Expression Analysis

- Orthogroup Delineation: Perform orthogroup analysis using OrthoFinder v2.5.1 with DIAMOND for sequence similarity searches and MCL for clustering [6].

- Expression Profiling: Utilize RNA-seq data from databases (IPF database, CottonFGD, Cottongen) to examine expression patterns across tissues and stress conditions [6].

Diagram 1: Genome-wide gene identification workflow. This pipeline illustrates the sequential steps for identifying and characterizing domain-encoding genes across multiple plant genomes.

Protocol for Evidence-Guided Genome Re-annotation

This protocol describes an evidence-based approach to improve existing genome annotations using multi-omics data and advanced assembly techniques.

Sample Preparation and Sequencing

- High-Quality DNA Extraction: Use phenol-chloroform extraction for high-molecular-weight DNA, verifying quality via Nanodrop (OD260/280: 1.8-2.0) and agarose gel electrophoresis [31].

- Long-Read Sequencing: Perform PacBio HiFi library preparation using SMRTbell Express Template Prep Kit 2.0 and sequence on PacBio Sequel II systems [31].

Genome Assembly and Assessment

- De Novo Assembly: Execute assembly using Hifiasm with default parameters, followed by haploid duplication removal [31].

- Polishing and Quality Control: Conduct three rounds of polishing with Racon v1.5.0. Assess completeness with BUSCO v5.2.2 using appropriate lineage datasets (e.g., metazoa_odb10) [31].

- Contamination Screening: Use Blobtools v1.1.1 with BLAST against NCBI NT database (e-value: 1e-5) to identify and remove non-target DNA [31].

Structural Annotation and Repeat Masking

- Repeat Element Annotation: Construct de novo repeat library with RepeatModeler v2.0.1, then mask repeats using RepeatMasker v4.1.7 with RepBase database [31].

- Gene Prediction: Employ multiple approaches including Augustus v3.3.2 for de novo prediction and evidence-guided prediction using transcriptomic data from related species [31] [32].

- Functional Annotation: Annotate genes through similarity searches against curated databases and assign functional terms based on domain architecture and homology.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Genomic Re-annotation

| Category | Item/Software | Specification/Version | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wet Lab | PacBio SMRTbell Express Template Prep Kit 2.0 | Commercial kit | HiFi library preparation for long-read sequencing [31] |

| Type II collagenase | 2 mg/ml | Tissue dissociation for sample preparation [31] | |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Hifiasm | Default parameters | De novo genome assembly from long reads [31] |

| BUSCO | v5.2.2 | Genome/completeness assessment using conserved orthologs [31] [32] | |

| RepeatModeler/RepeatMasker | v2.0.1/v4.1.7 | De novo repeat identification and masking [31] | |

| Racon | v1.5.0 | Genome consensus polishing and error correction [31] | |

| BlobTools | v1.1.1 | Taxonomic contamination screening [31] | |

| OrthoFinder | v2.5.1 | Orthogroup inference and evolutionary analysis [6] | |

| Databases | Pfam | Pfam-A.hmm | Protein domain families and HMM profiles [6] [7] |

| BUSCO | Lineage-specific datasets | Benchmarking universal single-copy orthologs [31] [32] | |

| RepBase | 20181026 | Curated database of repetitive elements [31] |

Diagram 2: Evidence-guided genome re-annotation pipeline. This workflow incorporates quality control checkpoints (diamond shapes) to ensure assembly and annotation quality at critical stages.

Applications in Plant Gene Research

Comparative Analysis of Plant Immune Receptor Architectures

The combination of genome-wide identification and re-annotation strategies has proven particularly powerful for elucidating the diversity of plant immune receptors. Comprehensive surveys of nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat (NLR) genes across multiple plant species have revealed substantial architectural variation, including numerous non-canonical domain arrangements [7]. These NLRs with integrated domains (NLR-IDs) represent evolutionary innovations where fusions between NLRs and additional protein domains create "integrated decoys" that enable direct recognition of pathogen effector proteins [7].

Studies examining 40 plant genomes identified 720 NLR-IDs involving both recently formed and conserved fusions, highlighting how domain integration events have repeatedly occurred across angiosperm evolution [7]. The integrated domains often correspond to known pathogen targets, supporting the hypothesis that these architectures evolve to intercept pathogen effectors during infection. For example, the Arabidopsis RRS1-R protein carries an integrated WRKY domain that mimics the effector targets of bacterial pathogens, enabling recognition of multiple effectors through a single integrated domain [7].

Diversification and Functional Validation of Disease Resistance Genes

Genome-wide analyses of NBS-domain-containing genes across 34 plant species identified 12,820 genes classified into 168 distinct domain architecture classes [6]. This remarkable diversity includes both classical patterns (NBS, NBS-LRR, TIR-NBS) and species-specific structural arrangements, revealing the extensive evolutionary innovation within this key gene family. Expression profiling of these genes under various biotic and abiotic stresses demonstrated specific upregulation of certain orthogroups in tolerant genotypes, providing candidates for functional validation [6].

Functional characterization through virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) confirmed the role of specific NBS genes in disease resistance. Silencing of GaNBS (OG2) in resistant cotton compromised resistance to cotton leaf curl disease, validating its importance in viral defense [6]. Protein-ligand and protein-protein interaction studies further demonstrated strong interactions between putative NBS proteins and ADP/ATP, as well as core proteins of the cotton leaf curl disease virus, elucidating potential mechanisms of action [6].

Genome-wide identification and re-annotation strategies provide powerful frameworks for advancing plant genomics research, particularly in the context of comparative domain architecture analysis. The integration of long-read sequencing technologies with evidence-guided annotation pipelines significantly enhances genome quality and gene model accuracy, enabling more reliable characterization of complex gene families. These approaches have revealed remarkable diversity in plant immune receptor architectures and identified numerous evolutionary innovations through domain integration events.

Standardized protocols for gene family identification and genome re-annotation, as detailed in this application note, offer researchers comprehensive methodologies to investigate domain architecture evolution across plant species. The continued refinement of these strategies, coupled with emerging technologies such as single-molecule sequencing and pan-genome analyses, will further expand our understanding of how protein domain arrangements shape plant gene function and evolutionary adaptation. These insights have significant implications for crop improvement, particularly in developing durable disease resistance through engineering of optimized immune receptor architectures.

Single-Cell and Spatial Transcriptomics for Cell-Type Specific Profiling

Single-cell and spatial transcriptomics have revolutionized plant biology by enabling the resolution of gene expression down to the level of individual cells within their native tissue context. These technologies overcome the limitations of traditional bulk RNA sequencing, which averages gene expression across heterogeneous cell populations, thereby obscuring cell-type-specific transcriptional signatures and rare cellular states [33] [34]. For research focused on the comparative analysis of domain architecture in plant genes, such as nucleotide-binding site (NBS) domain genes, these high-resolution techniques provide an indispensable toolset. They allow researchers to correlate the expansive diversity of gene domain architectures with precise spatiotemporal expression patterns across different cell types, developmental stages, and in response to environmental stresses [6]. This integration is pivotal for moving beyond mere sequence annotation to understanding the functional specialization of gene families at a cellular resolution, ultimately illuminating how genomic diversity translates into cellular heterogeneity and organismal function.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and spatial transcriptomics represent complementary approaches for dissecting cellular heterogeneity. scRNA-seq profiles the transcriptomes of individual cells isolated from dissociated tissues, revealing distinct cell subtypes, developmental trajectories, and rare cell states that are masked in bulk analyses [35] [34]. However, this process inherently loses the original spatial context of cells within the tissue. Spatial transcriptomics directly addresses this limitation by mapping gene expression patterns onto the two-dimensional or three-dimensional tissue architecture, often integrating high-throughput transcriptomic data with high-resolution tissue imaging [33] [35].