Evolution and Innovation: A Comparative Genomic Analysis of NBS Domain Genes in Plant Immunity

This article provides a comprehensive synthesis of current research on Nucleotide-Binding Site (NBS) domain genes, the primary class of disease resistance (R) genes in plants.

Evolution and Innovation: A Comparative Genomic Analysis of NBS Domain Genes in Plant Immunity

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive synthesis of current research on Nucleotide-Binding Site (NBS) domain genes, the primary class of disease resistance (R) genes in plants. Covering foundational concepts to advanced applications, we explore the remarkable diversity and evolution of NBS genes across land plants, from mosses to major crops. The review details state-of-the-art bioinformatics and machine learning methodologies for gene identification, addresses key challenges in analyzing this complex gene family, and presents case studies on the functional validation of specific NBS genes against viral, fungal, and bacterial pathogens. Tailored for researchers and scientists in plant genomics and drug development, this analysis highlights how understanding plant immune receptors can inform broader strategies for disease resistance and therapeutic discovery.

Unveiling the Diversity and Evolutionary History of NBS Domain Genes

Plant immunity relies on a sophisticated innate immune system where nucleotide-binding site (NBS) domain genes play a pivotal role as the largest class of plant disease resistance (R) genes [1]. These genes encode proteins that are vital for plant defense, enabling the detection of pathogen-derived molecules and initiating robust defense responses [2]. The NBS domain forms the core of a larger superfamily of proteins known as NLRs (Nucleotide-binding Leucine-rich Repeat receptors) [3] [4]. These intracellular immune receptors are modular proteins, typically consisting of a variable N-terminal domain, a central NBS (NB-ARC) domain, and C-terminal leucine-rich repeats (LRRs) [1] [2]. The NBS domain functions as a molecular switch, binding and hydrolyzing ATP/GTP to provide energy for downstream signaling processes [5] [6], while the LRR domain is primarily involved in pathogen recognition [7] [5].

This guide provides a comparative analysis of NBS domain genes across plant species, detailing their classification, distribution, and evolution. We present standardized experimental protocols for their identification and characterization, supported by quantitative data and visualizations of immune signaling pathways, to serve as a resource for researchers and drug development professionals.

Classification and Genomic Distribution of NBS Genes

Classification of NBS Gene Subfamilies

Based on the structure of the N-terminal domain, NBS-encoding genes are classified into distinct subfamilies, which have diverged to perform specialized functions in plant immunity [3] [1].

- TNL (TIR-NBS-LRR): Characterized by a Toll/Interleukin-1 Receptor (TIR) domain. These genes are predominantly found in dicots and are absent in most monocots [7] [8].

- CNL (CC-NBS-LRR): Feature a Coiled-Coil (CC) domain at the N-terminus. This subclass is present in both monocots and dicots and often represents the most abundant type [1] [9].

- RNL (RPW8-NBS-LRR): Contain a Resistance to Powdery Mildew 8 (RPW8) domain. Unlike TNLs and CNLs, RNLs typically function downstream in signal transduction rather than in direct pathogen recognition [1] [9].

In addition to these canonical architectures, plants possess numerous truncated forms (lacking LRRs or N-terminal domains) and NLRs with Integrated Domains (NLR-IDs). These integrated domains can act as "baits" for pathogen effectors, enabling novel recognition capabilities [4].

Comparative Quantitative Analysis Across Species

The number and composition of NBS genes vary dramatically across plant species, influenced by their evolutionary history and pathogen pressures. The table below summarizes a comparative analysis from recent studies.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of NBS-Encoding Genes Across Plant Species

| Plant Species | Family | Total NBS Genes | CNL | TNL | RNL | Notable Features | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis thaliana | Brassicaceae | 167 | 69 (41%) | 92 (55%) | 6 (4%) | Model dicot with balanced TNL/CNL | [8] |

| Brassica oleracea | Brassicaceae | 157 | 89 (57%) | 62 (39%) | 6 (4%) | CNL expansion post-WGT | [8] |

| Xanthoceras sorbifolium | Sapindaceae | 180 | 155 (86%) | 23 (13%) | 2 (1%) | "First expansion then contraction" pattern | [1] |

| Dinnocarpus longan | Sapindaceae | 568 | 502 (88%) | 43 (8%) | 23 (4%) | Strong recent gene expansion | [1] |

| Vernicia montana | Euphorbiaceae | 149 | 98 (66%) | 12 (8%) | 2 (1%) | Resistant to Fusarium wilt | [5] |

| Vernicia fordii | Euphorbiaceae | 90 | 49 (54%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | Susceptible to Fusarium wilt; TNL loss | [5] |

| Akebia trifoliata | Lardizabalaceae | 73 | 50 (68%) | 19 (26%) | 4 (5%) | Low number; uneven chromosomal distribution | [6] |

| Dendrobium officinale | Orchidaceae | 74 | 10 (14%) | 0 (0%) | N/A | No TNL genes identified; common in monocots | [7] |

The data reveals several key trends. First, the number of NBS genes is highly dynamic, even within the same family, as seen in the Sapindaceae species where D. longan has over three times the number of genes found in X. sorbifolium [1]. Second, the dominance of the CNL subclass is a recurring theme across many angiosperms [1] [9]. Third, the absence of TNLs in monocots like orchids is a well-established phenomenon, potentially driven by the deficiency of the NRG1/SAG101 signaling pathway [7]. Finally, comparative analyses of resistant and susceptible varieties, such as in tung trees (Vernicia), can pinpoint specific gene losses (e.g., TNLs in susceptible V. fordii) associated with disease susceptibility [5].

Genomic Architecture and Evolution

NBS-encoding genes are not randomly distributed within plant genomes. They are frequently organized in clusters located in hot-spot regions on chromosomes [2] [6]. These clusters can be homogeneous (containing the same type of NLR) or heterogeneous (containing diverse NLR classes or even mixed with other receptor genes) [2]. This arrangement is primarily driven by gene duplication events, including tandem duplications and whole-genome duplications (WGD), which facilitate the birth of new resistance specificities [2] [8]. Following duplication, genes undergo a process of birth and death, with some copies being preserved through natural selection while others are lost or become pseudogenes [2]. This dynamic leads to the distinct evolutionary patterns observed in different plant lineages, such as "expansion and contraction" or "continuous expansion" [1] [9].

Research into NBS domain genes relies on a suite of bioinformatic tools and genomic resources. The following table outlines key solutions for identification and characterization.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for NBS Gene Analysis

| Research Tool | Type | Primary Function in NBS Research | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|---|

| HMMER | Software | Identifying NBS domain-containing proteins in genome assemblies using hidden Markov models. | Search with NB-ARC (PF00931) HMM profile [3] [1] [5]. |

| Pfam / NCBI-CDD | Database | Validating the presence of protein domains (NBS, TIR, CC, LRR, RPW8). | Confirm domain architecture of candidate genes [1] [7] [6]. |

| OrthoFinder | Software | Inferring orthogroups and gene families across multiple species. | Reconstructing evolutionary history and classifying NBS genes [3]. |

| MEME Suite | Web Tool | Discovering conserved protein motifs within NBS domains and other regions. | Identifying structural motifs specific to CNL, TNL, or RNL subfamilies [9] [6]. |

| RNA-seq Data | Data | Profiling gene expression under various conditions (biotic/abiotic stress, different tissues). | Identifying differentially expressed NBS genes in resistant vs. susceptible cultivars [3] [5]. |

| Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) | Experimental Method | Functional validation of NBS genes through transient silencing. | Knocking down a candidate NBS gene (e.g., GaNBS) to test its role in disease resistance [3] [5]. |

Experimental Protocols for Identification and Functional Characterization

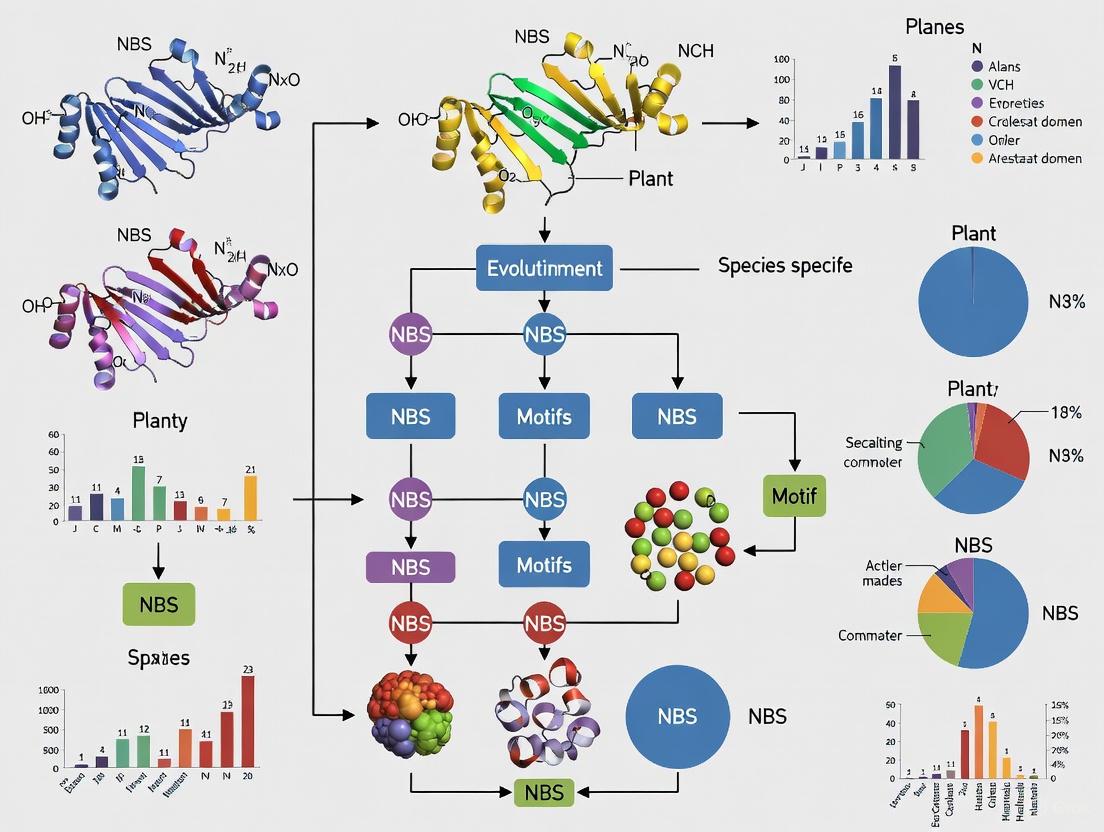

A standardized pipeline for genome-wide identification and functional analysis of NBS genes is critical for comparative studies. The workflow below outlines the key stages from identification to functional validation.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for NBS gene analysis

Detailed Methodological Protocols

Protocol 1: Genome-Wide Identification of NBS-Encoding Genes

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used in multiple comparative genomic studies [3] [1] [8].

- Data Collection: Obtain the latest genome assembly and annotation files for the target species from public databases (e.g., NCBI, Phytozome, species-specific databases).

- HMMER Search: Perform a hidden Markov model (HMM) search against the predicted proteome using the NB-ARC domain model (Pfam accession: PF00931). Use the

hmmsearchtool from the HMMER package with default parameters or a stringent e-value cutoff (e.g., 1.1e-50) [3]. - BLAST Search: Conduct a complementary BLASTP search using known NBS protein sequences as queries against the proteome, with an e-value threshold of 1.0 [1] [9].

- Data Curation: Merge the candidate sequences from both searches and remove redundant entries.

- Domain Validation: Confirm the presence of the NBS domain in all remaining candidates by analyzing them against the Pfam and NCBI Conserved Domain Database (CDD) with an e-value of 10⁻⁴ [1] [7]. Identify additional domains (TIR, CC, LRR, RPW8) using HMM profiles and specialized tools like COILS or Marcoil for CC domains [8].

Protocol 2: Functional Validation via Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS)

VIGS is a powerful technique for rapid functional characterization, as demonstrated in studies on cotton and tung tree NBS genes [3] [5].

- Candidate Gene Selection: Select a target NBS gene (e.g., a gene highly expressed in resistant cultivars upon pathogen infection).

- Vector Construction: Clone a 200-300 bp fragment specific to the target gene into a VIGS vector (e.g., TRV-based pYL156 or pYL279).

- Plant Material & Inoculation: Grow plants (e.g., resistant cotton or tung tree) to the 2-4 leaf stage. Inoculate by agroinfiltration, where Agrobacterium tumefaciens harboring the VIGS construct is injected into the leaves.

- Control Groups: Include plants inoculated with an empty vector (negative control) and a vector carrying a phytoene desaturase (PDS) gene fragment (positive control for silencing efficiency).

- Silencing Confirmation: After 2-3 weeks, assess silencing efficiency by measuring target gene transcript levels in silenced plants compared to controls using quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR).

- Phenotypic Assay: Challenge the silenced and control plants with the target pathogen. Monitor disease symptoms, measure pathogen biomass, and assess physiological changes to determine the role of the silenced NBS gene in disease resistance.

NBS-Mediated Immune Signaling Pathways

NBS-LRR proteins are central to effector-triggered immunity (ETI), a robust immune response that often culminates in a hypersensitive response (HR) to restrict pathogen spread [7] [2]. The signaling pathways differ based on the NBS subfamily involved. The diagram below illustrates the core ETI signaling pathway and the distinct roles of TNL and CNL receptors.

Diagram 2: Core ETI signaling pathways

As depicted, TNL and CNL proteins act as sensors that directly or indirectly recognize pathogen effectors [1] [9]. This recognition triggers a conformational change in the NBS domain, facilitating nucleotide exchange (ADP to ATP) and activating the receptor [2]. Activated TNLs signal through the EDS1-PAD4-SAG101 protein complex, while the signaling pathway for CNLs is less defined but may involve other components [7]. Both pathways converge on RNL proteins (e.g., NRG1, ADR1), which function as helper NLRs to transduce the defense signal downstream [1] [9]. This leads to the activation of defense genes, a burst of reactive oxygen species, and often the initiation of the hypersensitive response, a form of programmed cell death at the infection site [2].

Plant immunity relies on a sophisticated surveillance system mediated by intracellular receptors known as nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat receptors (NLRs). These proteins detect pathogen effector molecules and initiate robust defense responses, culminating in effector-triggered immunity (ETI) [10] [11]. NLRs are classified into major structural classes based on their N-terminal domains, which dictate their signaling mechanisms and functional specializations. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the Toll/Interleukin-1 Receptor (TNL), Coiled-Coil (CNL), and Non-TNL classes, examining their structural features, evolutionary patterns, and activation mechanisms to inform research and development in plant disease resistance.

Classification and Structural Features

The NLR superfamily in plants is divided into two major classes based on the N-terminal domain, with a third category encompassing atypical configurations.

Table 1: Major Structural Classes of Plant NLR Genes

| Class | N-Terminal Domain | Key Domains & Architecture | Prevalence & Distribution | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNL | Toll/Interleukin-1 Receptor (TIR) | TIR-NBS-LRR; TIR domain has enzymatic activity (NAD+ cleavage) | Abundant in dicots; scarce in most monocots [11] | MRT1, MRT2, MIST1 (Arabidopsis) [10]; RPP1, RPS4 [11] |

| CNL | Coiled-Coil (CC) | CC-NBS-LRR; CC domain forms signaling-competent complexes | Most abundant class in monocots; found across all angiosperms [3] [11] | Sr33, MLA10, Rx, RPS2, RPS5 (Arabidopsis and cereals) [11]; ZAR1 (forms resistosome) [10] |

| Non-TNL / nTNL | Non-TIR, various domains | Includes RPW8-NLRs (RNLs); other atypical domain architectures | Least abundant class; RNLs often function as "helper NLRs" [10] [3] | ADR1, NRG1 (helper RNLs) [3]; Proteins with TIR-NBS-TIR-Cupin1, Sugartr-NBS domains [3] |

Table 2: Functional and Evolutionary Characteristics

| Characteristic | TNLs | CNLs | Non-TNLs / nTNLs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Signaling Mechanism | TIR domain forms holoenzyme, produces signaling molecules (e.g., cADPR) [10] | CC domain inserts into plasma membrane, potential ion channel activity [10] [11] | Varied; RNLs signal through CC domain and can be required for TNL/CNL immunity [10] [3] |

| Activation Complex | TIR-domain tetramer [10] | CC-domain pentamer (resistosome) [10] | Not fully characterized for all types |

| Regulatory Mechanisms | Targeted by miRNAs (e.g., miR825-5p); generate phasiRNAs for amplified silencing [10] | Regulated by intramolecular interactions (e.g., EDVID motif with NB domain) [11] | Less studied; likely subject to transcriptional and post-transcriptional control |

| Evolutionary Dynamics | Ancient origin; expanded in dicots; birth-and-death evolution with gene loss/duplication [3] [12] | Massive expansion in flowering plants; high sequence diversity in CC domain [3] [11] | Includes conserved helper NLRs (RNLs) and lineage-specific genes with novel domain fusions [3] |

Experimental Approaches for Comparative Analysis

Genome-Wide Identification and Classification

Protocol for NBS Domain Identification and Classification:

- Sequence Retrieval: Obtain genome assemblies and protein sequences from public databases (e.g., NCBI, Phytozome) [3].

- Domain Screening: Use HMMER-based tools (e.g.,

PfamScan.pl) with the NB-ARC (PF00931) Hidden Markov Model (HMM) profile to identify candidate NBS-containing genes. A typical e-value cutoff is1.1e-50for stringency [3]. - Architecture Classification: Analyze the domain architecture of identified genes using HMM scans or InterProScan to detect associated N-terminal (TIR, CC, RPW8) and C-terminal (LRR) domains. Classify genes into TNL, CNL, or Non-TNL categories based on the presence of TIR, CC, or other N-terminal domains, respectively [3].

- Orthogroup Analysis: Use tools like OrthoFinder with the DIAMOND algorithm for sequence similarity searches and the MCL algorithm for clustering to define orthogroups (groups of genes descended from a single gene in the last common ancestor). This helps identify core, conserved lineages and species-specific expansions [3].

Functional Validation through Gene Silencing

Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) Protocol:

- Candidate Gene Selection: Select a target NBS gene (e.g.,

GaNBSfrom cotton) based on expression profiles under stress [3]. - Vector Construction: Clone a ~300-500 bp fragment of the target gene into a VIGS vector (e.g., TRV-based pYL192 series).

- Plant Inoculation: Agrobacterium tumefaciens strains harboring the VIGS construct are grown, resuspended in induction media, and infiltrated into cotyledons or true leaves of young plants.

- Phenotyping: After silencing is established (typically 2-3 weeks post-infiltration), challenge plants with the target pathogen. Assess disease symptoms, pathogen biomass, and compare to control plants (silenced with an empty vector) [3].

- Validation: Use qRT-PCR to confirm the reduction of target gene transcript levels and quantify pathogen titer.

Diagram Title: NLR Class Signaling Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for NLR Gene Analysis

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| HMMER/PfamScan | Identifies NBS (NB-ARC) domains and other architectural domains in protein sequences [3]. | Genome-wide identification and classification of NLRs into TNL, CNL, and Non-TNL classes [3]. |

| OrthoFinder | Infers orthogroups and gene families from whole-genome data; elucidates evolutionary relationships [3]. | Comparing NLR repertoires across species to identify conserved orthogroups (e.g., OG2, OG6) and lineage-specific expansions [3]. |

| VIGS Vectors (e.g., TRV-based) | Enables transient, sequence-specific silencing of target genes in plants [3]. | Functional validation of candidate NBS genes (e.g., GaNBS in cotton) by assessing susceptibility upon silencing [3]. |

| NBS Profiling Primers | Degenerate primers targeting conserved NBS motifs (P-loop, Kinase-2, GLPL) amplify NBS tags for sequencing [13]. | Profiling the R-gene repertoire and allelic diversity in plant populations without whole-genome sequencing [13]. |

| RNA-seq Datasets (e.g., from IPF, CottonFGD) | Provides expression data (FPKM) across tissues and stress conditions [3]. | Identifying NLR genes with putative defense roles based on upregulation under biotic/abiotic stress [3]. |

The structural dichotomy between TNLs and CNLs represents a fundamental evolutionary strategy in plant immunity, with distinct signaling mechanisms (TIR-enzymatic activity versus CC-mediated resistosome formation) converging on effective pathogen resistance [10] [11]. Non-TNLs, particularly RNLs, play critical, complementary roles as helper NLRs. Comparative genomics reveals that these gene families undergo dynamic evolution, driven by birth-and-death processes and gene duplication, resulting in lineage-specific expansions and losses [3] [12]. A deep understanding of these classes, their interactions, and regulatory networks—including miRNA-mediated silencing as exemplified by the miR825-5p/TNL module [10]—provides a robust foundation for developing durable, broad-spectrum resistance in crops through modern biotechnological approaches.

The evolutionary transition of plants from aquatic to terrestrial environments necessitated the development of sophisticated immune mechanisms to combat emerging pathogens. Central to this adaptive innovation are nucleotide-binding site (NBS) domain genes, which encode one of the largest and most critical families of plant disease resistance (R) genes [3] [14]. These genes provide plants with the capacity to recognize diverse pathogens and initiate robust defense responses [14].

The NBS-leucine-rich repeat (LRR) gene family exhibits remarkable structural diversity and evolutionary dynamics across the plant kingdom [15]. While comprehensive surveys have documented their expansion in numerous angiosperm species [16], studies in early land plants like bryophytes have revealed unexpected diversity and novel structural classes [16] [17]. Recent super-pangenome analyses of 123 bryophyte genomes further demonstrate that these non-vascular plants possess a substantially larger gene family space than vascular plants, with numerous unique and lineage-specific gene families [18].

This comparative guide objectively analyzes the diversification of NBS domain genes from bryophytes to angiosperms, synthesizing experimental data to elucidate evolutionary patterns and functional conservation. We provide detailed methodologies for key experiments and visualization of signaling pathways to support research in plant immunity and drug development.

Evolutionary History and Diversification Patterns

Deep Evolutionary Origins

NBS-LRR genes originated during early plant colonization of land, with the NBS domain combining with LRR domains coinciding with this evolutionary transition [16] [17]. Investigations across diverse plant lineages indicate that the common ancestor of bryophytes and vascular plants possessed the genetic machinery for NBS-mediated immunity, though the specific domain architectures have undergone substantial lineage-specific evolution [16] [18].

Bryophytes, as the sister group to all vascular plants, provide critical insights into the early evolution of plant immune genes. A comprehensive analysis of 138 bryophyte genomes revealed they possess a cumulative 637,597 nonredundant gene families compared to 373,581 in vascular plants, despite bryophytes having fewer genes per genome on average [18]. This expanded gene family diversity includes numerous NBS domain genes with unique domain architectures not observed in higher plants [16] [17].

Lineage-Specific Expansions and Losses

Analyses across angiosperms reveal dynamic expansion patterns influenced by both whole-genome duplications and small-scale duplication events [3] [15]. The three anciently diverged NBS-LRR classes (TNLs, CNLs, and RNLs) expanded into at least 23 lineages in the common ancestor of angiosperms [15]. A pattern of gradual expansion during the first 100 million years of angiosperm evolution was observed for CNLs, while TNL numbers remained relatively stable during this period [15].

Notably, an intense expansion of both TNL and CNL genes commenced at the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary, potentially reflecting convergent adaptive responses to dramatic environmental changes and increased fungal diversity during this period [15]. Lineage-specific losses also occurred, with TNL genes completely absent from monocot genomes despite their presence in basal angiosperms like Amborella trichopoda [15].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of NBS Domain Genes Across Plant Lineages

| Plant Group | Representative Species | Total NBS Genes | TNLs | CNLs | RNLs | Unique Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bryophytes | Physcomitrella patens | 65 | 9 | 11 | - | PK-NBS-LRR (PNL) class [16] |

| Bryophytes | Marchantia polymorpha | 43 | - | 7 | - | Hydrolase-NBS-LRR (HNL) class [16] |

| Basal Angiosperm | Amborella trichopoda | 105 | 15 | 89 | 1 | Represents ancestral angiosperm NBS repertoire [15] |

| Eudicots | Arabidopsis thaliana | ~150 | ~62 | ~88 | - | Well-characterized reference [14] |

| Eudicots | Medicago truncatula | 571 | - | - | - | Highest number among surveyed angiosperms [15] |

| Monocots | Oryza sativa | >400 | 0 | >400 | - | Complete absence of TNL class [15] |

Structural and Functional Classification

Domain Architecture Diversity

NBS domain genes typically exhibit a modular structure with an N-terminal domain, central NBS domain, and C-terminal LRR region [14]. Based on N-terminal domain identity, these genes are primarily classified into TIR-NBS-LRR (TNL) and coiled-coil-NBS-LRR (CNL) classes [14] [15]. A third class, RPW8-NBS-LRR (RNL), functions as scaffold proteins in defense signaling [15].

Beyond these canonical classes, bryophytes possess novel structural variants not found in angiosperms. In the moss Physcomitrella patens, researchers identified a PK-NBS-LRR (PNL) class characterized by an N-terminal protein kinase domain [16] [17]. Liverworts like Marchantia polymorpha possess a distinct Hydrolase-NBS-LRR (HNL) class featuring an N-terminal α/β-hydrolase domain [16] [17]. These novel classes exhibit unique intron positions and phase characteristics, suggesting independent evolutionary origins [16].

Motif Conservation and Variation

The NBS domain contains several conserved motifs (P-loop, RNBS-A, Kinase-2, RNBS-B, RNBS-C, GLPL, RNBS-D, and MHDV) that facilitate nucleotide binding and molecular switch functions [16] [14]. Phylogenetic analyses reveal closer relationships between HNL, PNL, and TNL classes, with CNLs representing a more divergent lineage [16].

Table 2: Conserved Motifs in the NBS Domain and Their Functional Roles

| Motif Name | Consensus Sequence | Position | Functional Role | Conservation Across Plant Lineages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-loop | GxPGSGKS | N-terminus | ATP/GTP binding | Universal in all plant NBS domains [16] |

| RNBS-A | FLHIACxF | After P-loop | Domain stability | Divergent between TNL/CNL classes [16] |

| Kinase-2 | LVLDDVW | Middle | ATP hydrolysis | Highly conserved [16] |

| RNBS-B | GLPLAL | Middle | Domain folding | Variable [16] |

| RNBS-C | GSRIIITTRD | Middle | Unknown | Divergent between TNL/CNL classes [16] |

| GLPL | GLPLA | C-terminus | LRR interaction | Highly conserved [16] |

| RNBS-D | CFAL | C-terminus | Signaling regulation | Divergent between TNL/CNL classes [16] |

| MHDV | MHDIV | C-terminus | Nucleotide exchange | Highly conserved [16] |

Genomic Distribution and Organization

Chromosomal Arrangement and Gene Clustering

NBS-encoding genes typically display non-random chromosomal distribution, frequently organized in clusters resulting from both segmental and tandem duplication events [19] [14]. Comparative analyses in asparagus species revealed that NLR genes in A. officinalis, A. kiusianus, and A. setaceus all exhibit clustering patterns across chromosomes, with adjacent NLR pairs often separated by ≤8 genes [19].

This clustering facilitates unequal crossing-over and gene conversion, generating variation in copy number and sequence diversity [14]. Studies in lettuce have identified two evolutionary patterns: type I genes evolve rapidly with frequent gene conversions, while type II genes evolve slowly with rare gene conversion events [14].

Evolutionary Dynamics and Selection Pressures

NBS genes evolve through a birth-and-death process characterized by gene duplication, sequence diversification, and pseudogenization [14] [20]. Different protein domains experience distinct selection pressures, with the NBS domain typically under purifying selection to maintain functional integrity, while LRR regions experience diversifying selection to generate recognition specificities [14].

Recent research has revealed that microRNA targeting represents an important regulatory mechanism for NBS-LRR genes, with diverse miRNA families emerging to target highly duplicated NBS-LRRs [21]. These miRNA-NBS-LRR interactions likely help balance the benefits and costs of maintaining large NBS-LRR repertoires [21].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Genome-Wide Identification and Classification

Protocol 1: Identification of NBS Domain Genes

- Data Collection: Obtain genome assemblies and annotation files from public databases (NCBI, Phytozome, Plaza) [3].

- Domain Screening: Use PfamScan.pl HMM search script with default e-value (1.1e-50) and Pfam-A_hmm model to identify genes containing NB-ARC domains [3].

- Sequence Validation: Extract candidate sequences and validate through domain architecture analysis using InterProScan and NCBI's Batch CD-Search [19].

- Classification: Categorize genes based on complete domain architecture using Pfam and PRGdb databases [19].

Protocol 2: Evolutionary and Phylogenetic Analysis

- Orthogroup Construction: Use OrthoFinder v2.5.1 with DIAMOND for sequence similarity searches and MCL clustering algorithm for gene grouping [3].

- Multiple Sequence Alignment: Perform alignment using MAFFT 7.0 or Clustal Omega [3] [19].

- Phylogenetic Reconstruction: Construct maximum likelihood trees using FastTreeMP or MEGA with 1000 bootstrap replicates [3] [19].

- Duplication Analysis: Identify tandem duplication events by analyzing genomic clustering patterns [3].

Experimental Workflow for Comprehensive NBS Gene Analysis

Expression Profiling and Functional Validation

Protocol 3: Transcriptomic Analysis of NBS Genes

- Data Retrieval: Obtain RNA-seq data from specialized databases (IPF database, CottonFGD, Cottongen) and NCBI BioProjects [3].

- Data Categorization: Classify expression data into tissue-specific, abiotic stress-specific, and biotic stress-specific categories [3].

- Expression Quantification: Extract FPKM values and process through transcriptomic pipelines [3].

- Visualization: Generate heat maps to visualize differential expression patterns across conditions [3].

Protocol 4: Functional Validation through Genetic Approaches

- Genetic Variation Analysis: Identify sequence variants between susceptible and tolerant accessions through whole-genome comparisons [3].

- Protein Interaction Studies: Conduct protein-ligand and protein-protein interaction assays to validate interactions with pathogen effectors [3].

- Functional Characterization: Implement virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) to assess gene function in resistant varieties [3].

- Phenotypic Assessment: Evaluate disease symptoms and pathogen titers in silenced plants [3].

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

NBS-LRR Activation and Signal Transduction

NBS-LRR proteins function as molecular switches in plant immunity, transitioning between ADP-bound inactive states and ATP-bound active states [14] [22]. The NBS domain facilitates nucleotide binding and hydrolysis, with the LRR domain implicated in both effector recognition and intramolecular interactions [22].

Research on the potato Rx protein (a CNL) revealed that intramolecular interactions between domains maintain the protein in an autoinhibited state in the absence of pathogen elicitors [22]. Pathogen recognition induces conformational changes through sequential disruption of these interactions, leading to activation [22]. Specifically, the Rx protein exhibits interactions between its CC and NBS-LRR domains that are disrupted in the presence of the potato virus X coat protein elicitor [22].

NBS-LRR Protein Activation Pathway

Regulatory Networks

The expression of NBS-LRR genes is tightly regulated due to the potential fitness costs associated with their inappropriate activation [21] [19]. MicroRNA-mediated regulation represents a crucial layer of control, with diverse miRNA families (e.g., miR482/2118) targeting conserved NBS-LRR motifs [21]. These miRNAs typically target highly duplicated NBS-LRRs, while heterogeneous NBS-LRR families are less frequently targeted [21].

Analyses of NLR genes in asparagus species revealed their promoters contain numerous cis-elements responsive to defense signals and phytohormones, indicating complex transcriptional regulation [19]. Domesticated species like A. officinalis show both contraction of NLR gene repertoire and reduced induction of retained NLR genes compared to wild relatives, suggesting artificial selection has impacted regulatory networks [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for NBS Gene Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Specific Example | Application | Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genome Databases | NCBI, Phytozome, Plaza | Gene identification | Source of genome assemblies and annotations | [3] |

| Domain Databases | Pfam, InterProScan | Domain architecture analysis | Identification of NBS and associated domains | [3] [19] |

| HMM Models | Pfam-A_hmm model | Domain screening | Identification of NB-ARC domains | [3] |

| Orthology Tools | OrthoFinder v2.5.1 | Evolutionary analysis | Orthogroup construction and classification | [3] |

| Phylogenetic Software | FastTreeMP, MEGA | Evolutionary analysis | Phylogenetic tree construction | [3] [19] |

| Expression Databases | IPF database, CottonFGD | Expression profiling | Source of RNA-seq data | [3] |

| Promoter Analysis Tools | PlantCARE | Regulatory element identification | Prediction of cis-acting regulatory elements | [19] |

| Motif Analysis Tools | MEME Suite | Conserved motif prediction | Identification of conserved NBS motifs | [19] |

| VIGS Systems | Virus-induced gene silencing | Functional validation | Transient gene silencing in plants | [3] |

The comparative analysis of NBS domain genes across plant species reveals both conserved evolutionary patterns and lineage-specific innovations. Bryophytes possess unexpected diversity with novel NBS classes like PNL and HNL, while angiosperms exhibit dynamic expansions particularly following the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary. The structural and functional conservation of NBS domains across 500 million years of plant evolution underscores their fundamental role in plant immunity.

Future research directions should include comprehensive functional characterization of bryophyte-specific NBS classes, exploration of regulatory networks controlling NBS gene expression, and utilization of comparative genomic insights for crop improvement. The experimental methodologies and resources outlined in this guide provide a foundation for advancing our understanding of plant immunity mechanisms across the evolutionary spectrum.

Gene duplication is a fundamental engine of evolutionary innovation, providing the raw genetic material for the evolution of new functions and adaptive traits. Among the various mechanisms of gene duplication, whole-genome duplication (WGD) and tandem duplication (TD) represent two fundamentally distinct processes with profound implications for genome evolution and gene content [23]. WGD involves the duplication of an entire genome, creating massive genetic redundancy across all loci, while TD generates localized clusters of duplicated genes through the repeated copying of individual genes or genomic segments [24]. Understanding the relative contributions and evolutionary consequences of these duplication mechanisms is particularly crucial for interpreting the expansion and diversification of key gene families, such as the nucleotide-binding site (NBS) domain genes that comprise the majority of plant disease resistance (R) genes [3] [8]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of WGD and TD, synthesizing current genomic evidence to elucidate their distinct roles in shaping plant genome architecture, functional diversity, and adaptive potential.

Comparative Analysis of Duplication Mechanisms

Fundamental Characteristics and Genomic Signatures

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Whole-Genome and Tandem Duplication

| Feature | Whole-Genome Duplication (WGD) | Tandem Duplication (TD) |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Scale | Entire genome duplication [23] | Single genes or small genomic segments [23] |

| Frequency of Occurrence | Episodic, rare events (every ~10-100 million years) [23] | Continuous, frequent events [23] |

| Typical Gene Copy Number | All genes doubled in a single event [24] | 2 or more copies in close proximity [25] |

| Genomic Distribution | Genome-wide, creating systemic blocks [23] | Localized clusters on specific chromosomes [23] |

| Evolutionary Half-Life | Long-term retention of some duplicates [26] | Short half-life, rapid turnover [23] |

| Inheritance Pattern | All genes duplicated simultaneously | Gene-by-gene basis |

Evolutionary Dynamics and Functional Consequences

The differential mechanisms of WGD and TD impose distinct selective pressures and evolutionary trajectories on their duplicated products, leading to significant functional biases in gene retention and diversification.

Table 2: Evolutionary Outcomes of Whole-Genome and Tandem Duplication

| Evolutionary Parameter | Whole-Genome Duplication (WGD) | Tandem Duplication (TD) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Functional Bias | Dosage-sensitive genes, transcription factors, core cellular processes [26] [25] | Environmental response genes, biotic/abiotic stress resistance [24] [25] |

| Typical Expression Divergence | Gradual subfunctionalization or conservation of broad expression [26] | Rapid neofunctionalization or asymmetric expression [26] |

| Selection Pressure | Weaker purifying selection, especially initially [26] | Stronger selective pressure [23] |

| Retention of Redundant Copies | High for dosage-sensitive genes [26] | Low, rapid functional divergence or loss [23] |

| Role in Adaptation | Major genomic revolutions, morphological innovation [23] | Continuous adaptation to rapidly changing environments [24] [23] |

| Impact on NBS Gene Evolution | Large-scale expansion followed by fractionation [8] | Species-specific, lineage-specific expansion of R-genes [3] [8] |

The relationship between duplication mechanism and gene function is particularly striking. WGD-derived genes are preferentially retained for dose-sensitive genes involved in essential cellular processes like DNA-binding, transcription factor activity, and core metabolism [26] [25]. This retention bias is explained by the gene balance hypothesis, which predicts that components of multiprotein complexes require stoichiometric balance [26]. In contrast, TD-derived genes are overwhelmingly enriched for functions in environmental interactions, particularly defense responses against pathogens and abiotic stresses [24]. This functional specialization makes TD a critical mechanism for the rapid expansion of disease resistance gene families, including NBS-encoding genes [3].

Figure 1: Evolutionary trajectories of gene duplicates following whole-genome versus tandem duplication. WGD and TD produce duplicates with distinct functional biases and evolutionary fates, shaping genome evolution through complementary mechanisms.

Experimental Approaches for Studying Duplication Events

Genomic and Bioinformatics Workflows

Research in this field relies on integrated genomic, transcriptomic, and bioinformatic approaches to identify duplication events and characterize their functional consequences.

Table 3: Key Experimental and Bioinformatics Methodologies

| Methodology | Primary Application | Key Insights Generated |

|---|---|---|

| Synteny Analysis | Identifying WGD-derived genomic blocks [23] | Reveals ancient polyploidization events and systemic relationships |

| Ks Distribution Analysis | Dating duplication events [23] | Identifies peaks of duplication events in evolutionary history |

| Hidden Markov Model (HMM) Profiling | Identifying NBS domain genes [3] [8] | Enables genome-wide identification of resistance gene families |

| OrthoFinder/OrthoMCL | Classifying orthologous groups [3] | Distinguishes lineage-specific expansion from shared gene families |

| RNA-seq Expression Profiling | Characterizing expression divergence [26] [3] | Reveals subfunctionalization and neofunctionalization patterns |

| Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) | Functional validation of candidate genes [3] | Tests role of specific duplicates in disease resistance |

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for studying duplication events and their functional consequences. Integrated genomic and functional approaches enable comprehensive characterization of WGD and TD events and their roles in evolution.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Studying Gene Duplication

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Databases | Phytozome, BRAD, Bolbase, PLAZA [3] [8] | Provide annotated genome sequences and comparative genomics tools |

| Domain Databases | Pfam (PF00931 for NBS domain) [3] [8] | Hidden Markov Models for identifying protein domains |

| Bioinformatics Tools | DupGen_finder, OrthoFinder, DIAMOND, MCLE [3] [23] | Identify and classify duplication modes and orthologous groups |

| Expression Databases | IPF Database, CottonFGD, NCBI BioProjects [3] | Provide RNA-seq data for expression divergence analysis |

| Functional Validation Tools | Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) vectors [3] | Enable functional characterization of duplicated genes |

Case Study: NBS Domain Gene Evolution in Plants

The evolution of NBS-encoding disease resistance genes provides an excellent model for understanding the complementary roles of WGD and TD. These genes are crucial for plant immunity and exhibit remarkable diversity across plant species.

Duplication Patterns in Brassica Species

Comparative analysis of NBS-encoding genes in Brassica oleracea, Brassica rapa, and Arabidopsis thaliana reveals a complex evolutionary history shaped by both WGD and TD [8]. The Brassica lineage experienced a whole-genome triplication (WGT) event after its divergence from Arabidopsis ~16 million years ago [8]. Following this WGT event, NBS-encoding homologous gene pairs on triplicated regions were rapidly deleted or lost. However, subsequent species-specific gene amplification occurred through TD, leading to the expansion of NBS gene families in each lineage [8]. This pattern demonstrates how large-scale WGD events can provide genetic raw material that is subsequently refined and specialized through small-scale TD events.

Expression Divergence and Functional Specialization

Spatial transcriptomics technologies have revealed that the mechanism of duplication profoundly influences expression divergence between paralogs [26]. Duplication mechanisms that preserve cis-regulatory landscapes, such as WGD and TD, typically yield paralogs with more conserved expression profiles [26]. However, over time, TD-derived genes often diverge asymmetrically, with one copy maintaining broad expression while the other specializes in specific cell types or conditions [26]. This expression specialization is particularly relevant for NBS-encoding genes, which may evolve new specificities against rapidly evolving pathogens through TD-mediated expansion [3].

Recent research on NBS-encoding genes in cotton demonstrated how tandemly duplicated orthogroups (OG2, OG6, and OG15) show putative upregulation in different tissues under various biotic and abiotic stresses [3]. Functional validation through virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) of a candidate gene (GaNBS from OG2) confirmed its role in virus resistance, illustrating the adaptive significance of TD-derived NBS genes [3].

Evolutionary Implications and Future Directions

The complementary actions of WGD and TD have shaped plant genome evolution through distinct but interconnected mechanisms. WGD events provide evolutionary revolutions—cataclysmic genomic changes that create massive genetic redundancy and enable major functional innovations over long evolutionary timescales [23]. In contrast, TD provides continuous evolutionary tinkering—a steady supply of genetic variants that enable fine-tuned adaptations to rapidly changing environmental conditions, especially in stress response pathways [24] [23].

This duality is particularly evident in the evolution of plant immune systems. WGD events have created large reservoirs of genetic material that can be co-opted for disease resistance functions, while TD enables the rapid, lineage-specific expansion of resistance gene families in response to emerging pathogen threats [3] [8]. The functional specialization of TD-derived genes for environmental interactions makes this mechanism particularly important for adaptive evolution in rapidly changing environments [24].

Future research directions include leveraging spatial transcriptomics to understand expression divergence at cellular resolution [26], exploring the role of epigenetic modifications in duplicate gene regulation, and investigating how duplication mechanisms influence protein interaction networks and metabolic pathways. Understanding these evolutionary dynamics has practical implications for crop improvement, suggesting that manipulating both WGD (through synthetic polyploidy) and TD (through gene editing) may provide strategies for enhancing disease resistance and environmental resilience in agricultural systems.

Plant disease resistance (R) genes are a key component of the innate immune system that protects plants from a diverse range of pathogens. The nucleotide-binding site (NBS) gene family represents one of the largest classes of R genes, encoding proteins that play critical roles in effector-triggered immunity (ETI). These proteins typically contain an NB-ARC (nucleotide-binding adaptor shared by APAF-1, R proteins, and CED-4) domain and are often accompanied by C-terminal leucine-rich repeats (LRRs) and variable N-terminal domains such as TIR (Toll/Interleukin-1 receptor), CC (coiled-coil), or RPW8 (Resistance to Powdery Mildew 8). Based on these domain architectures, NBS-encoding genes are classified into several types including TNL (TIR-NBS-LRR), CNL (CC-NBS-LRR), RNL (RPW8-NBS-LRR), and various truncated forms lacking complete domain suites [27] [3].

The distribution and evolution of NBS-encoding genes vary considerably across plant species. In flowering plants, substantial gene expansion has occurred, resulting in extensive NBS repertoires. For instance, the ANNA database documents over 90,000 NLR genes from 304 angiosperm genomes, including 18,707 TNL genes, 70,737 CNL genes, and 1,847 RNL genes. This stands in stark contrast to bryophytes like Physcomitrella patens, which possess only around 25 NLRs, suggesting that significant gene expansion occurred primarily in flowering plants [3].

This case study examines the genomic expansion of NBS domain genes in cotton (Gossypium species) and peanut (Arachis species), two economically important crops with distinct evolutionary histories. Through comparative analysis, we explore how differential expansion patterns and evolutionary trajectories of NBS genes have influenced disease resistance profiles in these crop species.

Genomic Distribution of NBS Genes in Cotton and Peanut

NBS Gene Profiles in Cotton Species

Comparative genomic analyses reveal significant variation in NBS-encoding gene content across cotton species. Studies have identified 246, 365, 588, and 682 NBS-encoding genes in G. arboreum (A-genome), G. raimondii (D-genome), G. hirsutum (allotetraploid), and G. barbadense (allotetraploid), respectively. The distribution of these genes among chromosomes is nonrandom and uneven, with a tendency to form clusters. Notably, the two allotetraploid cotton species possess approximately twice the number of NBS genes compared to their diploid progenitors, suggesting preservation and potential expansion following hybridization [27].

Domain architecture analysis shows substantial differences between cotton species. G. arboreum and G. hirsutum possess a greater proportion of CN (CC-NBS), CNL, and N (NBS-only) genes, and a lower proportion of NL (NBS-LRR), TN (TIR-NBS), and TNL genes compared to G. raimondii and G. barbadense. The most dramatic difference is observed in TNL genes, with G. raimondii and G. barbadense containing approximately seven times the percentage of TNL genes found in G. arboreum and G. hirsutum. This asymmetric distribution has functional implications, as TNL genes are associated with resistance to Verticillium wilt [27].

Table 1: NBS-Encoding Gene Distribution in Cotton Species

| Species | Genome Type | Total NBS Genes | CN (%) | CNL (%) | N (%) | NL (%) | TNL (%) | Other (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G. arboreum | Diploid (A) | 246 | 17.89 | 32.52 | 23.98 | 21.54 | 2.03 | 2.04 |

| G. raimondii | Diploid (D) | 365 | 10.68 | 29.32 | 16.99 | 24.38 | 13.70 | 4.93 |

| G. hirsutum | Allotetraploid (AD) | 588 | 15.14 | 28.06 | 28.57 | 26.19 | 0.85 | 1.19 |

| G. barbadense | Allotetraploid (AD) | 682 | 13.49 | 20.97 | 25.07 | 30.79 | 6.45 | 3.23 |

NBS Gene Profiles in Peanut Species

Peanut exhibits a different pattern of NBS gene expansion. In cultivated peanut (A. hypogaea cv. Tifrunner), 713 full-length NBS-LRR genes have been identified, with 229 containing TIR domains, 118 containing CC domains, and surprisingly, 26 sequences containing both TIR and CC domains—a feature not observed in the diploid progenitors. This suggests that genetic exchange or gene rearrangement likely resulted in domain fusion after tetraploidization [28].

Wild peanut species show distinct NBS gene profiles. Studies have identified 393 and 437 NBS-LRR genes in A. duranensis (A-genome) and A. ipaensis (B-genome), respectively. Among these, 278 and 303 were full-length sequences. Comparative analysis revealed that A. ipaensis has more gene clusters than A. duranensis, possibly due to more frequent tandem duplication events. The LRR domains in these genes mainly underwent purifying selection, though most LRR8 domains experienced positive selection, suggesting adaptive evolution [29].

Table 2: NBS-Encoding Gene Distribution in Peanut Species

| Species | Genome Type | Total NBS Genes | Full-Length Genes | TNL (%) | CNL (%) | TNL+CNL (%) | NBS-WRKY Fusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. duranensis | Diploid (A) | 393 | 278 | 32.1 | 67.9 | 0 | Not reported |

| A. ipaensis | Diploid (B) | 437 | 303 | 31.4 | 68.6 | 0 | Not reported |

| A. hypogaea | Allotetraploid (AB) | 713 | 713 | 32.1 | 67.3 | 0.36 | 3 genes |

Evolutionary Dynamics and Selection Pressures

Evolutionary Patterns in Cotton

Phylogenetic analysis in cotton reveals that TIR-NBS genes of G. barbadense are closely related to those of G. raimondii, while G. hirsutum shows greater similarity to G. arboreum. Synteny analysis supports this pattern, indicating that G. hirsutum inherited more NBS-encoding genes from G. arboreum, while G. barbadense inherited more from G. raimondii. This asymmetric evolution of NBS-encoding genes may explain differential disease resistance between these species [27].

Notably, G. raimondii and G. barbadense demonstrate higher resistance to Verticillium wilt, while G. arboreum and G. hirsutum are more susceptible. This correlation suggests that TNL genes, which are more abundant in Verticillium-resistant species, may play significant roles in resistance to this pathogen. The differences in NBS gene repertoire between tetraploid cottons and their diploid progenitors indicate that allopolyploidization was followed by either preferential gene retention from one progenitor or differential gene loss [27].

Evolutionary Patterns in Peanut

In peanut, evolutionary analysis reveals that NBS-LRR proteins and LRR domains have undergone relaxed selection in cultivated peanut compared to wild diploids. Particularly noteworthy is the preferential loss of LRR domains in cultivated peanut, which may partially explain its generally lower disease resistance compared to wild relatives. Despite this trend, quantitative trait locus (QTL) analysis has identified 113 NBS-LRRs associated with response to late leaf spot, tomato spotted wilt virus, and bacterial wilt in cultivated peanut [28].

These resistance-associated NBS-LRRs in cultivated peanut were classified as 75 young and 38 old genes, indicating that young NBS-LRRs produced after tetraploidization play significant roles in disease resistance. This finding highlights the importance of recent gene evolution in adapting to pathogen pressures. The pangenome analysis of peanut further revealed substantial structural variations affecting NBS genes, with 1,335 domestication-related structural variations and 190 structural variations associated with seed size or weight identified [30] [28].

Methodologies for NBS Gene Identification and Analysis

Standard Bioinformatics Pipeline for NBS Gene Identification

The identification and classification of NBS-encoding genes typically follows a standardized bioinformatics workflow. First, genome sequences or protein databases are searched using Hidden Markov Model (HMM) profiles corresponding to the NB-ARC domain (PF00931) from the Pfam database. The HMMER software package is commonly employed with default e-value cutoffs (often 1.1e-50) to ensure stringent selection [3] [29].

Following initial identification, additional domains (TIR, CC, RPW8, LRR) are detected using complementary approaches:

- Pfam and SMART databases for TIR and LRR domains

- MARCOIL or Paircoil2 programs for CC domains (P-score cutoff typically 0.03)

- Custom parsing scripts to classify genes into architectural types based on domain combinations [27] [31] [29]

Evolutionary and Expression Analysis Methods

For evolutionary analysis, multiple sequence alignment of full-length protein sequences is performed using tools such as MAFFT or ClustalW with default parameters. Phylogenetic trees are constructed using maximum likelihood (ML) or neighbor-joining (NJ) methods implemented in MEGA or similar software, with bootstrap validation (typically 1000 replicates) [3] [29].

Selection pressure is assessed by calculating nonsynonymous (Ka) and synonymous (Ks) substitution rates using PAML or similar packages. Ka/Ks ratios >1, =1, and <1 indicate positive, neutral, and purifying selection, respectively [29].

Gene expression analysis under pathogen challenge typically involves:

- Pathogen inoculation under controlled conditions

- RNA extraction at multiple time points

- qRT-PCR with gene-specific primers

- Reference gene normalization (e.g., actin)

- Statistical analysis of expression differences [29]

Disease Resistance Associations

Cotton Resistance Profiles and NBS Gene Correlations

Cotton species show distinct resistance patterns that correlate with their NBS gene profiles. Verticillium wilt, caused by the soilborne fungal pathogen Verticillium dahliae, presents a particularly clear example of this relationship. G. raimondii is nearly immune to this pathogen, and G. barbadense is typically resistant or highly resistant, whereas G. arboreum and G. hirsutum are often susceptible. This resistance pattern strongly correlates with the abundance of TNL genes, which are significantly more prevalent in resistant species [27].

For Fusarium wilt, caused by Fusarium oxysporum, the resistance pattern differs. G. barbadense is often more susceptible to F. oxysporum compared to G. arboreum and G. hirsutum, indicating that different NBS gene types may confer resistance to different pathogens [27].

Analysis of the correlation between disease resistance QTL and NBS-encoding genes in G. raimondii suggests that more than half of disease resistance QTL are associated with NBS-encoding genes. This agrees with previous studies establishing that more than half of plant resistance genes are NBS-encoding genes [31].

Peanut Resistance Profiles and NBS Gene Correlations

In peanut, resistance to various pathogens has been associated with NBS-LRR genes. In A. duranensis, A. ipaensis, and A. hypogaea cv. Tifrunner, NBS-LRRs have been identified within QTL regions responsive to late leaf spot, tomato spotted wilt virus, and bacterial wilt. Specifically, 2, 39, and 113 NBS-LRRs were associated with these diseases in the respective species [28].

Expression profiling following Aspergillus flavus infection revealed differential expression patterns between wild and cultivated peanuts. In A. duranensis, upregulated expression of NBS-LRR genes was continuous after infection, while these genes responded temporally in cultivated peanut (A. hypogaea). This temporal expression pattern in cultivated peanut may contribute to its greater susceptibility to A. flavus infection and subsequent aflatoxin contamination [29].

Recent functional validation using virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) demonstrated that silencing of a specific NBS gene (GaNBS, OG2) in resistant cotton reduced its resistance, confirming the functional role of NBS genes in disease resistance [3].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for NBS Gene Analysis

| Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Function/Application | Example Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioinformatics Tools | HMMER v3.1b2 | Domain-based gene identification | Identifying NB-ARC domains in genome assemblies [27] |

| Pfam Database | Protein family annotation | Verifying NBS, TIR, LRR domains [3] | |

| SMART | Protein domain analysis | Detecting functional domains in NBS proteins [31] | |

| MARCOIL/Paircoil2 | Coiled-coil domain prediction | Identifying CC domains in NBS proteins [31] [29] | |

| OrthoFinder | Orthogroup inference | Clustering NBS genes across species [3] | |

| Evolutionary Analysis | MAFFT v7.0 | Multiple sequence alignment | Aligning NBS protein sequences [3] [29] |

| MEGA v6.0/5.05 | Phylogenetic analysis | Constructing evolutionary trees [31] [29] | |

| PAML v4.0 | Selection pressure analysis | Calculating Ka/Ks ratios [29] | |

| Experimental Validation | Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) | Functional characterization | Validating NBS gene function in resistance [3] |

| qRT-PCR with SYBR Green | Expression profiling | Measuring NBS gene expression under pathogen challenge [29] |

This case study reveals both convergent and divergent patterns in NBS gene expansion between cotton and peanut. Both crops show significant expansion of NBS genes in their allotetraploid forms compared to diploid progenitors, yet the specific evolutionary trajectories and functional outcomes differ substantially.

In cotton, asymmetric evolution following allopolyploidization resulted in species-specific NBS gene profiles that correlate with differential disease resistance. The inheritance patterns from diploid progenitors to allotetraploid descendants significantly influenced resistance capabilities, particularly against Verticillium wilt. The abundance of TNL genes emerged as a key factor in Verticillium resistance [27].

In peanut, the evolutionary story is characterized by relaxed selection on NBS-LRR proteins and preferential loss of LRR domains in cultivated varieties, potentially explaining their generally lower disease resistance compared to wild relatives. Despite this trend, the production of young NBS-LRR genes after tetraploidization appears crucial for maintaining disease resistance capabilities. The discovery of genes with both TIR and CC domains in cultivated peanut, but not in diploid progenitors, highlights the ongoing evolution and innovation in the NBS gene family following polyploidization [28].

These comparative genomic analyses provide valuable insights for crop improvement strategies. Understanding the specific NBS gene architectures associated with disease resistance in these crops enables more targeted breeding approaches and genetic engineering strategies to enhance disease resistance while maintaining favorable agronomic traits.

Advanced Computational and Experimental Methods for NBS Gene Discovery

This guide provides a comparative analysis of three foundational bioinformatics tools—HMMER, Pfam, and OrthoFinder—within the context of comparative genomics research on Nucleotide-Binding Site (NBS) domain genes in plants. The evaluation, grounded in experimental data from recent studies, demonstrates that an integrated pipeline leveraging these tools enables high-accuracy domain identification, orthogroup inference, and evolutionary analysis, providing critical insights into plant disease resistance gene families.

The table below summarizes the core functionality and typical usage of each tool in a comparative genomics workflow.

| Tool | Primary Function | Role in Comparative Genomics | Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|

| HMMER | Profile Hidden Markov Model (HMM) search for sensitive sequence homology detection [32] | Identifies protein domains (e.g., NB-ARC) in query sequences against domain databases like Pfam [3]. | Statistical probability models for detecting remote homologs. |

| Pfam | Curated database of protein families and domains [33] | Provides the HMM profiles (e.g., PF00931 for NB-ARC) used by HMMER to annotate domains in gene sets [3]. | Large collection of multiple sequence alignments and HMMs. |

| OrthoFinder | Phylogenetic orthology inference from whole proteomes [34] | Clusters genes into orthogroups, infers gene trees and species trees, and identifies gene duplication events [3]. | Graph-based clustering (orthogroups) and phylogenetic tree analysis. |

Performance Comparison and Benchmarking Data

Orthology Inference Accuracy

OrthoFinder has been extensively benchmarked against other methods. The table below summarizes its performance on the Quest for Orthologs benchmark, a community-standardized evaluation [34].

| Method | Ortholog Inference Accuracy (SwissTree Test) | Ortholog Inference Accuracy (TreeFam-A Test) | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| OrthoFinder (Default) | 3-24% higher than other methods [34] | 2-30% higher than other methods [34] | Most accurate ortholog inference; provides comprehensive phylogenetic outputs [34]. |

| Other Methods (e.g., InParanoid, OrthoMCL, OMA) | Lower accuracy range [34] | Lower accuracy range [34] | Varying strengths, but none consistently second best [34]. |

A key reason for OrthoFinder's high accuracy is its phylogenetic approach, which uses gene trees to distinguish orthologs from paralogs, overcoming limitations of score-based heuristic methods that can be confounded by variable sequence evolution rates [34].

Application Performance in NBS Gene Research

A 2024 study on NBS genes in plants utilized a pipeline integrating these tools. The following table summarizes the scale and performance of this integrated approach [3].

| Performance Metric | Result | Context and Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Genomes Analyzed | 34 plant species [3] | Broad taxonomic coverage from mosses to monocots and dicots. |

| NBS Genes Identified | 12,820 genes [3] | Demonstrates HMMER/Pfam's scalability for large-scale genome annotation. |

| Domain Architecture Classes | 168 classes identified [3] | Pfam-based domain annotation reveals extensive functional diversity. |

| Orthogroups (OGs) Clustered | 603 OGs with OrthoFinder [3] | Effective delineation of evolutionary lineages; identified core and species-specific OGs. |

Experimental Protocols for NBS Domain Gene Analysis

The following workflow, based on a published study [3], details a standard protocol for the comparative analysis of a gene family across multiple species.

Step 1: Identification of NBS Domain-Containing Genes

- Objective: To identify all genes containing the NBS (NB-ARC) domain in a set of proteomes.

- Method:

- Tool:

HMMER3(specificallyPfamScan.pl). - Database: Pfam-A.hmm model for the NB-ARC domain (PF00931).

- Parameters: A strict E-value cutoff of 1.1e-50 is used to ensure high-confidence matches [3].

- Output: A list of all genes containing the NBS domain for each species.

- Tool:

Step 2: Domain Architecture Classification

- Objective: To classify the identified NBS genes based on their full domain composition.

- Method:

- All additional domains (e.g., TIR, LRR, CC) associated with the NBS genes are identified using the same HMMER/Pfam workflow.

- Genes are classified into architectural classes based on the combination and order of their domains [3].

- Output: A comprehensive classification of classical (e.g., TIR-NBS-LRR) and species-specific structural patterns.

Step 3: Evolutionary Analysis and Orthogroup Inference

- Objective: To cluster NBS genes into orthogroups (groups of genes descended from a single gene in the last common ancestor of the species being compared) to understand evolutionary relationships.

- Method:

- Tool:

OrthoFinder v2.5.1. - Sequence Search: The

DIAMONDtool is used for fast all-vs-all sequence similarity searches [3]. - Clustering: The MCL algorithm clusters genes into orthogroups based on the similarity scores [3].

- Output: Orthogroups (OGs), which can be categorized as "core" (common across many species) or "unique" (species-specific).

- Tool:

Step 4: Phylogenetic and Duplication Analysis

- Objective: To infer evolutionary relationships and identify gene duplication events.

- Method:

- Tool:

OrthoFinder(internal workflow). - Alignment & Tree Building: OrthoFinder uses

MAFFTfor multiple sequence alignment andFastTreeMPfor maximum likelihood gene tree construction within orthogroups [3]. - Duplication Inference: OrthoFinder analyzes gene trees and the species tree to identify gene duplication events [3].

- Output: Rooted gene trees, a rooted species tree, and a list of gene duplication events.

- Tool:

The following diagram visualizes this integrated experimental workflow.

Diagram 1: Integrated bioinformatics pipeline for comparative analysis of NBS domain genes.

This table lists key databases, tools, and resources essential for conducting research in this field.

| Resource Name | Type | Function in the Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| Pfam Database [35] [33] | Protein Family Database | Provides the curated HMM profiles for identifying protein domains like the NB-ARC domain [3]. |

| DIAMOND [34] [3] | Sequence Similarity Search Tool | A faster alternative to BLAST for all-vs-all sequence searches, used by OrthoFinder for initial similarity comparisons [3]. |

| MAFFT [3] | Multiple Sequence Alignment Tool | Used for creating accurate alignments of protein sequences within orthogroups for phylogenetic analysis [3]. |

| FastTreeMP [3] | Phylogenetic Tree Inference Tool | Used for inferring approximate maximum-likelihood gene trees from multiple sequence alignments [3]. |

| EggNOG [36] [34] | Orthology Database | A public database of orthologous groups and functional annotation, useful for comparison and validation [37]. |

The integrated use of HMMER/Pfam for precise domain annotation and OrthoFinder for phylogenetic orthology inference creates a powerful and accurate pipeline for comparative genomic studies. Benchmarking data confirms that OrthoFinder outperforms other methods in ortholog detection accuracy, while real-world application in plant NBS gene research demonstrates the pipeline's robustness and scalability. This combination of tools enables researchers to reliably uncover evolutionary patterns and functional diversification in gene families critical for traits like disease resistance.

Machine Learning and Deep Learning Classifiers for R-protein Prediction

Plant resistance genes (R-genes), particularly those encoding nucleotide-binding site leucine-rich repeat (NBS-LRR or NLR) proteins, constitute a primary line of defense in the plant immune system, enabling recognition of pathogen effectors and initiation of effector-triggered immunity (ETI) [38] [39]. The identification and classification of these genes are critical for understanding plant defense mechanisms and for breeding disease-resistant crops. Traditional methods for R-gene identification, which rely on sequence similarity and domain search tools like BLAST, HMMER, and InterProScan, often struggle with the immense diversity and rapid evolution of these genes, frequently missing novel or highly divergent sequences [38]. The advent of machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) has begun to transform this field, offering powerful, alignment-free methods for the accurate prediction and classification of R-genes from sequence data alone. This guide provides a comparative analysis of contemporary computational classifiers for R-protein prediction, situating them within the broader research context of comparative NBS domain gene analysis across plant species [3]. We objectively evaluate the performance, underlying methodologies, and practical applications of these tools to assist researchers in selecting the most appropriate solutions for their work.

Traditional Methods and the Need for Advanced Classifiers

Conventional R-gene Identification Pipelines

Before the rise of ML/DL approaches, the standard pipeline for identifying NBS-LRR genes involved a multi-step process. Researchers typically began with a genome-wide search using tools like HMMER3 with Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) of the NB-ARC domain (PF00931) or performing BLASTP searches with known NBS sequences as queries [3] [39] [40]. Candidate genes were then subjected to domain analysis using PfamScan, NCBI-CDD, or SMART to confirm the presence of characteristic domains such as TIR, CC, LRR, and RPW8 [3] [40]. Finally, gene classification into subfamilies (e.g., TNL, CNL, RNL) was performed based on the combination of identified domains [39] [40].

Limitations of Traditional Approaches

While effective, these homology-based methods possess significant limitations. They often produce fragmented annotations due to the complex genomic structure of R-gene clusters and their tendency to be misidentified as repetitive elements [38]. Their performance drops considerably when sequence similarity to known R-genes is low, making them poorly suited for discovering novel R-gene classes in newly sequenced or non-model plant genomes [38]. The manual curation required to validate results is time-consuming and not scalable for large genomic studies.

Comparative Performance of ML/DL Classifiers

The following table summarizes the performance metrics of leading ML/DL-based R-gene prediction tools as reported in their respective studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of R-gene Prediction Tools

| Tool Name | Underlying Algorithm | Primary Function | Reported Accuracy | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRGminer [38] | Deep Learning (Dipeptide Composition) | R-gene identification & classification into 8 classes | 98.75% (k-fold), 95.72% (independent test) | High accuracy with MCC of 0.98; webserver available |

| DPFunc [41] | Deep Learning (GCN with Domain-guided Attention) | Protein function prediction, incl. defense response | Significant improvement over SOTA (Fmax: 16-27% increase) | Integrates domain info for interpretability; detects key functional residues |

| PCPIP [42] | Support Vector Machine (SVM) | Classification of native vs. non-native PPI interfaces | High performance on benchmarking datasets | Effective for identifying biologically relevant protein complexes |

Detailed Methodologies of Featured Classifiers

PRGminer: A Deep Learning Framework for R-gene Prediction

PRGminer is a dedicated DL tool designed specifically for the high-throughput prediction of plant R-genes. Its implementation occurs in two distinct phases [38].

Phase I: R-gene vs. Non-R-gene Classification

- Input Representation: The tool converts protein sequences into a numerical representation using dipeptide composition, which was found to yield superior performance compared to other sequence encoding methods.

- Model Architecture: A deep learning model processes this input to classify sequences as either R-genes or non-R-genes. The model achieves an accuracy of 98.75% in a k-fold training/testing procedure and 95.72% on an independent test set, with a high Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) of 0.98 and 0.91, respectively [38].

Phase II: R-gene Subclassification

- Process: Sequences predicted as R-genes in Phase I are subsequently classified into one of eight categories: CNL, TNL, TIR, RLK, RLP, LECRK, LYK, and KIN. This multi-classification achieved an overall accuracy of 97.55% in k-fold testing and 97.21% on an independent set [38].

- Availability: PRGminer is accessible as both a user-friendly webserver and a standalone tool, facilitating adoption by researchers with varying computational expertise.

DPFunc: Leveraging Domain Guidance for Functional Prediction

While not exclusively an R-gene predictor, DPFunc is a state-of-the-art DL model for general protein function prediction that can be powerfully applied to identify proteins involved in defense responses. Its methodology is notable for its integration of structural and domain information [41].

Workflow:

- Residue-level Feature Learning: The protein sequence is passed through a pre-trained protein language model (ESM-1b) to generate initial residue-level features. A protein structure-based contact map is constructed (from experimental or AlphaFold-predicted structures), and Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) layers propagate and update features between residues [41].

- Domain-guided Attention: Domain information is detected from the sequence using InterProScan. An attention mechanism, inspired by transformer architectures, then uses these domain embeddings to guide the model toward functionally crucial residues in the protein structure, creating an interpretable link between domain, structure, and function [41].

- Function Prediction: The weighted residue features are aggregated into a protein-level representation, which is used to predict Gene Ontology (GO) terms, including those related to immune responses.

Traditional ML: SVM for Interface Prediction (PCPIP)

Representing traditional machine learning approaches, PCPIP uses a Support Vector Machine (SVM) to classify protein-protein interaction (PPI) interfaces as native or non-native, which is valuable for validating interactions between R-proteins and pathogen effectors [42].

Methodology:

- Feature Engineering: The classifier relies on manually curated interface properties calculated by the PISA software, including accessible surface area (ASA), buried surface area (BSA), dissociation free energy, hydrogen bonds, and salt bridges [42].

- Training and Validation: The SVM model is trained on known dimer complexes and evaluated on benchmarking datasets, showing strong performance in distinguishing biologically relevant interfaces. This approach highlights the utility of expert-curated features, even alongside more complex DL models [42].

The workflow below illustrates the typical process for identifying and analyzing NBS-LRR genes, from initial identification to functional validation.

Diagram 1: R-gene Analysis Workflow

Successful R-gene prediction and analysis relies on a suite of computational tools and databases. The table below lists key resources.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Category | Tool/Database | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Genome Databases | NCBI Genome, Phytozome, Plaza, GDR | Source of plant genome sequences and annotations [3] [40] |

| Domain Analysis | HMMER, Pfam, NCBI-CDD, SMART | Identification of NBS, TIR, CC, LRR domains [3] [39] [40] |

| Evolutionary Analysis | OrthoFinder, MAFFT, IQ-TREE | Orthogroup clustering and phylogenetic tree construction [3] |

| Expression Analysis | IPF Database, CottonFGD, NCBI BioProject | RNA-seq data for expression profiling under stress [3] |

| Structure Prediction | AlphaFold2, P2Rank | Protein structure prediction and ligand-binding site analysis [43] [44] |

| Interaction Validation | PCPIP, STRING, BioGRID | PPI interface classification and known interaction data [45] [42] |

Integration with Comparative Analysis of NBS Domain Genes

Machine learning classifiers are profoundly enhancing large-scale comparative genomic studies of NBS genes. For instance, a recent analysis of 12,820 NBS genes across 34 plant species identified 168 distinct domain architecture classes, revealing both classical and species-specific patterns [3]. Tools like PRGminer can rapidly and accurately annotate such vast datasets, enabling researchers to focus on evolutionary analysis. This study further utilized expression profiling to identify key orthogroups (OGs) upregulated in response to cotton leaf curl disease and employed virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) to validate the role of a specific NBS gene (GaNBS in OG2) in viral defense [3]. The ability of DL models like DPFunc to pinpoint key functional residues [41] can directly inform such validation experiments by highlighting candidate regions for mutagenesis.

The integration of machine and deep learning classifiers into the plant immunology toolkit marks a significant advancement over traditional, homology-based methods for R-gene discovery. As demonstrated, tools like PRGminer offer high-throughput, accurate prediction and classification, while approaches like DPFunc provide deeper functional insights by linking sequence and structure to biological role. When used in conjunction with established evolutionary and expression analysis techniques, these classifiers empower researchers to decipher the complex landscape of plant disease resistance genes more efficiently and at an unprecedented scale, accelerating the development of resilient crop varieties.