From Code to Crop: Decoding Plant Genotype-to-Phenotype Relationships for Advanced Research and Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive examination of the methodologies and challenges in linking plant genomic information to observable traits, a field critical for accelerating crop improvement and plant-based drug discovery.

From Code to Crop: Decoding Plant Genotype-to-Phenotype Relationships for Advanced Research and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of the methodologies and challenges in linking plant genomic information to observable traits, a field critical for accelerating crop improvement and plant-based drug discovery. It explores the foundational principles of genetic and environmental interaction, details cutting-edge high-throughput phenotyping and machine learning approaches, and addresses key optimization challenges in data standardization and model interpretation. By comparing traditional and novel prediction models, it offers researchers and drug development professionals a validated framework for leveraging plant genotype-to-phenotype insights to enhance predictive breeding outcomes and identify valuable phytochemical compounds, ultimately bridging the gap between genomic data and tangible agricultural and pharmaceutical applications.

The Genetic Blueprint: Unraveling Core Principles and Complexities in Plant G2P Relationships

Defining the Genotype-to-Phenotype Paradigm in Plant Biology

Connecting genotype to phenotype represents a grand challenge in biology with particular significance for plant sciences [1]. In essence, this paradigm seeks to understand how an organism's genetic makeup (genotype) interacts with environmental factors to produce its observable characteristics (phenotype). For plants, this relationship dictates critical agronomic traits—from drought tolerance to yield potential—making its understanding essential for addressing global food security challenges [1]. The classical view of a linear relationship between single genes and traits has been dramatically reshaped by recent advances, revealing a complex interplay involving whole-genome dynamics, regulatory networks, and environmental interactions [1] [2]. This technical guide examines the current state of genotype-to-phenotype research in plants, focusing on mechanistic insights, experimental approaches, and emerging computational frameworks that are transforming this paradigm.

Fundamental Mechanisms Generating Phenotypic Variation

Genomic Architecture and Dynamics

Plant genomes are remarkably dynamic, with several key mechanisms generating the genetic diversity that fuels phenotypic variation:

Whole Genome Duplication (Polyploidy): Plants frequently undergo cycles of whole-genome duplication, creating multiple copies of their entire genetic material. These events provide raw genetic material for neo-functionalization and can lead to immediate phenotypic novelty. Studies in Tragopogon allotetraploids reveal that after polyploidization, genomes become mosaics through differential gene loss, resulting in populations that are genetically and phenotypically variable [1]. Similarly, polyploidy in Spartina has led to novel ecological functions and heritable biochemical abilities in lineages colonizing low-marsh areas [1].

Transposable Elements (TEs): These mobile genetic elements represent a major driver of plant genome plasticity and size evolution. TEs contribute significantly to the "dispensable genome"—genetic elements not shared by all individuals of a species—which may be key for adaptation [1]. Research shows TE silencing is developmentally regulated, with partial release during the juvenile-to-adult transition in maize leaves, creating another layer of developmental regulation [1].

Structural Variants and Presence-Absence Variation: Beyond single nucleotide polymorphisms, structural variants including major deletions, insertions, and rearrangements contribute substantially to phenotypic variation. These variants are routinely overlooked in conventional genome-wide association studies but can have profound phenotypic effects [3].

Molecular Bridges: From Gene to Function

The molecular pathways connecting genetic information to physiological function involve multiple regulatory layers:

Transcriptional and Post-Transcriptional Regulation: Gene expression regulation in plants relies on numerous mechanisms affecting different steps of mRNA life: transcription, processing, splicing, alternative splicing, transport, translation, storage, and decay [4]. Alternative splicing occurs in approximately 60% of Arabidopsis genes, significantly expanding the transcriptome and proteome diversity, with different splicing patterns in response to environmental stimuli enabling rapid adaptation [4].

Epigenetic Regulation: Plants utilize unique epigenetic mechanisms to control gene expression. Research in Arabidopsis thaliana has revealed that repressive chromatin states incorporating the histone variant H2A.Z along with the repressive mark H3K27me3 create a "lock" that keeps genes turned off, but one that includes a potential self-destruct switch for more dynamic regulation [5]. This combination contributes to developmental flexibility in plants, potentially enabling rapid phenotypic change.

Protein Conformational Ensembles: The traditional view that a gene encodes a single protein shape has been replaced by understanding that genes encode ensembles of conformations [2]. These dynamic structural states link genetic variation to phenotypic traits, with mutations altering the probabilities of different conformations rather than creating entirely new structures [2].

Table 1: Key Mechanisms Generating Genomic Diversity in Plants

| Mechanism | Impact on Genome | Phenotypic Consequences | Example Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Genome Duplication (Polyploidy) | Doubles chromosome number; provides genetic redundancy | Novel phenotypes, increased vigor, adaptation to new niches | Tragopogon, Spartina, Arabidopsis arenosa |

| Transposable Element Mobilization | Genome size expansion/contraction; new regulatory sequences | Altered gene expression patterns; developmental variability | Maize, Grapevine, Arabidopsis |

| Structural Variants | Presence-absence variation; gene copy number differences | Adaptive traits; disease resistance; environmental adaptation | Tomato, Maize, Arabidopsis |

| Epigenetic Modifications | Chromatin state changes; DNA methylation | Stable alterations in gene expression; phenotypic plasticity | Arabidopsis |

Experimental Approaches for Mapping Genotype to Phenotype

High-Throughput Phenotyping Technologies

Field-based, high-throughput phenotyping (FB-HTP) has emerged as a critical capability for quantifying phenotypic variation at scales matching genomic data [6]. These approaches use sensor and imaging technologies to enable rapid, low-cost measurement of multiple phenotypes across time and space:

Canopy Reflectance and Spectroscopy: Most FB-HTP applications utilize the interaction between the electromagnetic spectrum (400-2,500 nm) and plant canopies to infer physiological status [6]. Hyperspectral data can nondestructively infer leaf chemical properties, including canopy nitrogen and lignin content, providing insight into community-level phenotypes [6].

Multi-Sensor Fusion Platforms: Advanced platforms combine complementary sensors to provide more information than individual sensors alone. For example, platforms combining light curtains (measuring canopy height) with spectral reflectance sensors can predict aboveground biomass accumulation in maize more accurately than either sensor alone [6]. Advanced systems can capture details of plant physical structure, including canopy leaf angle, and produce 3D surface reconstructions [6].

Temporal Phenotyping: The longitudinal collection of phenotypic data enables detection of quantitative trait loci (QTL) with temporal expression patterns coinciding with specific growth stages. This approach has been used to study physiological processes underlying heat and drought responses in cotton populations under contrasting irrigation regimes [6].

Table 2: Sensor Technologies for Field-Based High-Throughput Phenotyping

| Sensor Type | Measured Parameters | Applications in Plant Research | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Red-Green-Blue (RGB) Cameras | Canopy coverage, color, texture | Growth monitoring, disease detection, phenological staging | Affected by ambient light conditions |

| Hyperspectral Imaging | Full spectral signature (400-2500 nm) | Leaf chemical composition, stress detection, photosynthetic efficiency | High data volume; complex analysis |

| Thermal Infrared | Canopy temperature | Plant water status, stomatal conductance, drought response | Affected by atmospheric conditions |

| 3D Sensors (LiDAR, Time-of-Flight) | Canopy structure, plant architecture, biomass estimation | Plant growth modeling, lodging assessment, architectural traits | Cost; computational requirements for data processing |

| Fluorescence Sensors | Chlorophyll fluorescence, photosynthetic efficiency | Photosynthetic performance, stress detection | Requires specific lighting conditions |

Genotyping and Association Mapping Approaches

Modern genotyping approaches have expanded beyond single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) to capture a wider range of genetic variation:

K-mer Based Association Mapping: This innovative approach uses raw sequencing data directly to derive short sequences (k-mers) that mark a broad range of polymorphisms independently of a reference genome [3]. Only after identifying k-mers associated with phenotypes are they linked to specific genomic regions. This method recapitulates associations found with SNPs but with stronger statistical support and discovers new associations with structural variants and regions missing from reference genomes [3].

Pangenome References: Rather than relying on a single reference genome, pangenomes capture the genomic diversity within a species, allowing researchers to expand genotyping from SNPs and indels to include gene presence-absence variation, which has been associated with disease resistance and stress tolerance [7].

Controlled Environment and High-Throughput Functional Studies

Deep Mutational Scanning: Advances in DNA synthesis and sequencing have enabled the development of assays capable of scoring comprehensive libraries of genotypes for fitness and various phenotypes in massively parallel fashion [8]. These approaches can measure competitive cellular fitness directly in bulk by tracking genotype frequencies during laboratory propagation of mixed cultures, providing precise quantitative fitness estimates [8].

Massively Parallel Genetics: Creative uses of next-generation sequencing technologies allow measurement of particular phenotypes for each genetic variant in large mixed libraries, enabling direct genotype-phenotype mapping on an unprecedented scale [8].

Computational and Modeling Frameworks

Traditional Statistical Approaches

Genomic Best Linear Unbiased Prediction (GBLUP): This linear modeling approach estimates the contribution of each SNP to phenotypes of interest and has seen significant success in plant breeding [7]. Its simplicity makes it straightforward to implement, and the contribution of each SNP is relatively easy to calculate.

Quantitative Trait Locus (QTL) Mapping: This approach aims to explain the genetic basis of variation in complex traits by linking phenotype data to genotype data [2]. However, quantifying traits remains challenging, with matters of trait definition, interdependence, and selection presenting ongoing difficulties [2].

Machine Learning and Deep Learning Approaches

Machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) algorithms can discover non-linear relationships within datasets, potentially capturing the complex relationships between genotype, phenotype, and environment more effectively than linear models [7]:

Random Forests: This ML method can capture patterns in high-dimensional data to deliver accurate predictions and account for non-additive effects. It has demonstrated superior performance compared to linear models like Bayesian LASSO and Ridge Regression BLUP, depending on the genetic architecture of the predicted trait [7].

Deep Neural Networks: Convolutional neural networks and feed-forward deep neural networks can outperform linear methods with correct optimization of hyperparameters [7]. Multi-trait DL models can help understand relationships between related traits for improved prediction [7].

G-P Atlas Framework: This innovative neural network framework uses a two-tiered denoising autoencoder approach that first learns a low-dimensional representation of phenotypes and then maps genetic data to these representations [9]. This data-efficient training process can predict many phenotypes simultaneously from genetic data and identify causal genes, including those acting through non-additive interactions that conventional approaches may miss [9].

Encoding Genetic Variation for Machine Learning

The most common form of encoding whole-genome SNP data for ML and DL is one-hot encoding, where each SNP position is represented by four columns corresponding to the four DNA bases (A, T, C, G), with presence indicated by 1 and absence by 0 [7]. However, strategies to reduce feature dimensionality are often necessary, including:

- Minor allele frequency filtering

- Feature selection based on genome-wide association studies

- Focus on rare variants with potentially large effects

- Integration of transcriptional data [7]

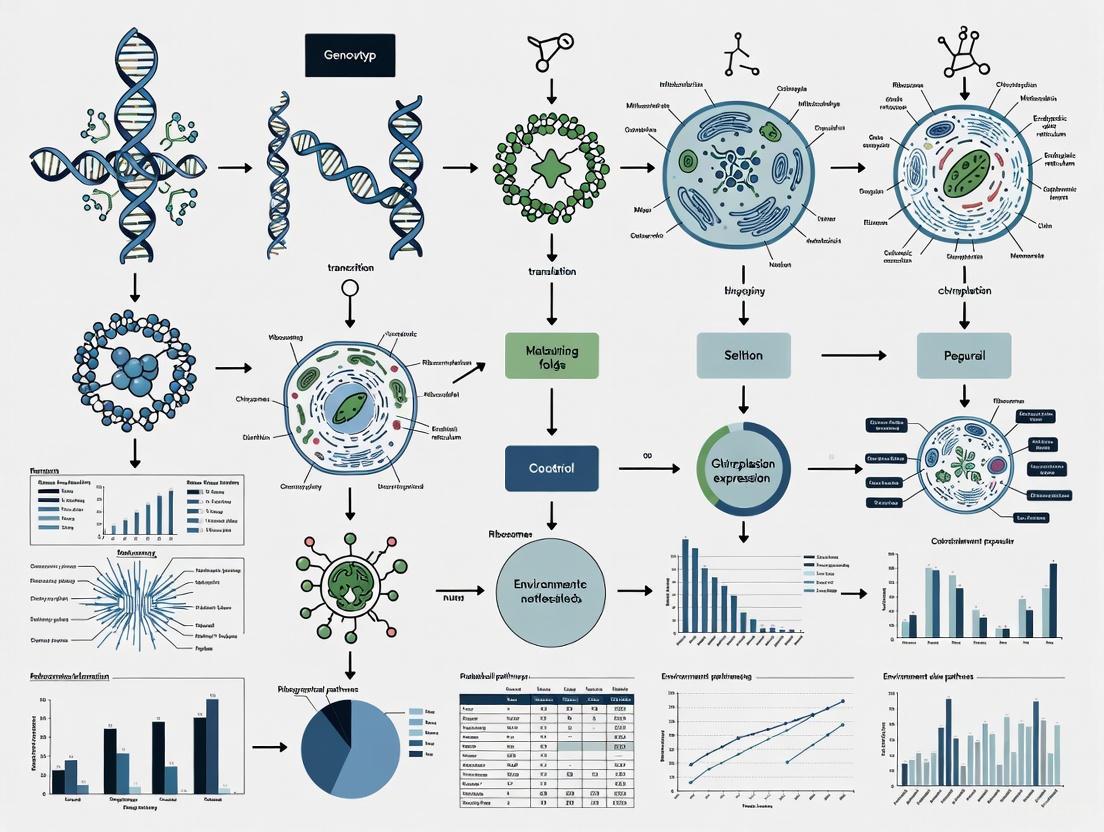

Figure 1: Computational Workflow for Genotype to Phenotype Prediction

Signaling Pathways Integrating Environmental Cues

Light Signaling and Retrograde Communication

Light induces massive reprogramming of gene expression in plants, affecting up to one-third of the transcriptome in Arabidopsis [4]. This regulation operates through multiple interconnected pathways:

Photoreceptor-Mediated Signaling: Plants sense light parameters through multiple photoreceptor families. Red and far-red light are sensed by phytochromes; blue and UV-A wavelengths by cryptochromes, phototropins, and Zeitlupe family members; and UV-B by the UVR8 photoreceptor [4].

Chloroplast Retrograde Signaling: Once green seedlings are established, chloroplasts play a key role in sensing light fluctuations and communicating these changes to the nucleus [4]. Operational retrograde signals dependent on light quantity/quality include:

- Redox signals from photosynthetic electron transport components, particularly the plastoquinone pool

- Reactive oxygen species (ROS) continuously produced during photosynthesis

- Metabolic signals reflecting photosynthetic efficiency [4]

Alternative Splicing Regulation by Light: Light regulates alternative splicing of Arabidopsis genes encoding proteins involved in RNA processing through chloroplast retrograde signals [4]. This effect is observed even in roots when communication with photosynthetic tissues remains intact, suggesting a mobile signaling molecule travels through the plant [4].

Figure 2: Light Signaling Pathway Integrating Environmental Cues

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

K-mer Based Genome-Wide Association Study Protocol

This protocol enables detection of genetic variants underlying phenotypic variation without complete genomes, capturing structural variants and presence-absence polymorphisms often missed in conventional GWAS [3]:

Sequence Data Processing:

- Begin with raw sequencing reads from population samples

- Generate all possible k-mers (short sequences of length k) from the reads

- Count k-mer frequencies across samples

Association Testing:

- Test each k-mer for association with the phenotype of interest

- Use statistical frameworks that account for population structure

- Apply multiple testing corrections to identify significantly associated k-mers

Genomic Localization:

- Map significantly associated k-mers to reference genomes where possible

- For k-mers that cannot be mapped, consider de novo assembly approaches

- Annotate genomic regions linked to associated k-mers

Validation:

- Confirm associations using orthogonal methods

- Validate structural variants through PCR or long-read sequencing

- Perform functional validation through transgenic approaches where feasible

Field-Based High-Throughput Phenotyping Protocol

This protocol enables large-scale, temporal phenotypic data collection under field conditions [6]:

Platform Selection and Sensor Integration:

- Select appropriate vehicle platform (UAS, high-clearance tractor, cable gantry) based on plot size and resolution requirements

- Integrate multiple complementary sensors (RGB, hyperspectral, thermal, 3D)

- Implement precision geopositioning systems for spatial accuracy

Data Collection Schedule:

- Establish regular imaging intervals throughout growing season

- Coordinate data collection with key developmental stages

- Include appropriate environmental monitoring (weather, soil conditions)

Data Processing and Feature Extraction:

- Preprocess raw sensor data (radiometric calibration, geometric correction)

- Extract vegetation indices and structural parameters

- Implement automated feature extraction pipelines

- Generate time-series data for growth trajectory analysis

Data Integration:

- Combine phenotypic data with genomic information

- Implement database solutions for large-scale data management

- Apply statistical models accounting for spatial and temporal correlations

Research Reagent Solutions for Genotype-Phenotype Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Example Use Cases | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis T-DNA Insertion Lines | Gene knockout and functional characterization | Reverse genetics, validation of candidate genes | Redundancy may require multiple knockouts |

| SNP Arrays | Genome-wide genotyping | Genomic selection, association studies | Limited to predefined variants; being supplanted by sequencing |

| Phage/Bacterial Display Libraries | High-throughput protein characterization | Protein-protein interactions, antibody generation | Limited to in vitro applications |

| Near-Isogenic Lines (NILs) | Fine-mapping of QTLs | Validation of candidate genes, epistasis studies | Time-consuming to develop |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Targeted genome editing | Functional validation, trait engineering | Off-target effects must be assessed |

| Reporter Constructs (GUS, GFP) | Spatial and temporal expression analysis | Promoter activity, protein localization | May not capture full regulatory context |

| Massively Parallel Reporter Assays | Functional assessment of regulatory elements | Identification of causal variants, enhancer characterization | Limited to sequences that can be synthesized and cloned |

The genotype-to-phenotype paradigm in plant biology is undergoing rapid transformation, driven by technological advances in both genotyping and phenotyping. The integration of machine learning approaches, particularly deep neural networks capable of capturing non-linear relationships and gene-gene interactions, promises to enhance our predictive capabilities [7] [9]. However, significant challenges remain, including the scarcity of high-quality, multi-dimensional datasets and the need for improved model interpretability.

Future research directions will likely focus on:

Multi-Omics Integration: Combining genomic, transcriptomic, epigenomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data to build more comprehensive models of biological systems.

Dynamic Modeling: Moving from static snapshots to dynamic models that capture phenotypic changes across developmental timescales and in response to environmental fluctuations.

Environment-Aware Models: Developing models that explicitly incorporate environmental variables and genotype-by-environment interactions, which are particularly important for plant adaptation and agricultural applications.

Single-Cell Resolution: Applying single-cell technologies to understand how genotype-phenotype relationships operate at cellular resolution within complex tissues.

The continuing evolution of the genotype-to-phenotype paradigm will require close collaboration between biologists, computer scientists, engineers, and mathematicians. By embracing the complexity of biological systems and developing more sophisticated models to capture this complexity, we move closer to predictive understanding of plant biology that can address fundamental scientific questions and pressing agricultural challenges.

The journey from genotype to phenotype in plants is governed by a complex landscape of genetic variations. These variations, ranging from single nucleotide changes to large structural rearrangements, form the fundamental basis for phenotypic diversity, environmental adaptation, and crop domestication. Understanding these genetic differences is crucial for unraveling the molecular mechanisms controlling traits of agricultural and ecological importance. Plant genomes contain diverse types of polymorphisms that collectively contribute to phenotypic variation, including single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), insertions-deletions (InDels), and presence-absence variations (PAVs), each with distinct characteristics, frequencies, and functional consequences [10] [11] [12]. These genetic variations serve as the raw material for evolutionary processes and provide the toolkit for plant breeders to develop improved varieties with enhanced yield, stress tolerance, and quality traits.

The investigation of genetic variations has transformed dramatically with advances in sequencing technologies and computational biology. Early studies relied on limited molecular markers, but contemporary research now leverages whole-genome sequencing and sophisticated bioinformatics tools to comprehensively characterize genetic diversity at unprecedented resolution [10] [12]. This technical evolution has enabled researchers to move beyond simply documenting genetic differences toward understanding their functional significance in shaping plant phenotypes. This review systematically examines the major types of genetic variations in plants, their detection methods, and their roles in bridging the gap between genetic makeup and observable traits.

Types and Characteristics of Genetic Variations

Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs)

SNPs represent the most abundant form of genetic variation in plant genomes, occurring when a single nucleotide (A, T, C, or G) differs between individuals of the same species [10] [12]. These variations are distributed throughout plant genomes, with their density and distribution varying significantly among species. For instance, in tea plants (Camellia sinensis), a comprehensive study identified 7,511,731 SNPs between two varieties, with an average density of 2,341 SNPs per megabase [11]. SNPs are generally classified as transitions (changes between purines or between pyrimidines) or transversions (changes between purines and pyrimidines), with transitions typically occurring more frequently than transversions—in tea plants, transitions accounted for 77.46% of SNPs with a transition/transversion ratio of 3.44 [11].

The functional impact of SNPs depends largely on their genomic location. SNPs within protein-coding regions can be categorized as synonymous (not altering the amino acid sequence) or non-synonymous (changing the amino acid sequence), with the latter having greater potential to affect protein function and consequently phenotypic traits [11]. SNPs in regulatory regions can influence gene expression by modifying transcription factor binding sites or other regulatory elements, while those in intergenic regions typically have no known functional effect [12]. In tea plants, only 6% of SNPs were located in genic regions, with the overwhelming majority (94%) found in intergenic regions [11]. Of the genic SNPs, 38,670 were synonymous and 50,841 were non-synonymous, potentially affecting protein function [11].

Table 1: Distribution and Characteristics of SNPs in Plants

| Category | Subtype | Frequency | Potential Impact | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| By Type | Transitions (G/A, C/T) | ~77% of SNPs [11] | Variable | Tea plant: 2,905,203 A/G and 2,913,570 C/T [11] |

| Transversions (A/C, A/T, C/G, G/T) | ~23% of SNPs [11] | Variable | Tea plant: nearly even distribution among four types [11] | |

| By Location | Intergenic | 94% of SNPs [11] | Often minimal | Tea plant: majority of 7+ million SNPs [11] |

| Genic | 6% of SNPs [11] | Variable | Tea plant: 440,298 SNPs [11] | |

| Coding (Non-synonymous) | 50,841 in tea plant [11] | Alters amino acid sequence | May affect protein function, enzyme activity [10] | |

| Coding (Synonymous) | 38,670 in tea plant [11] | No amino acid change | Generally neutral; may affect mRNA stability/splicing [10] | |

| Regulatory | Varies by genome | Alters gene expression | May affect transcription factor binding [12] |

Insertion-Deletion Polymorphisms (InDels)

InDels represent another major class of genetic variation characterized by the insertion or deletion of DNA segments ranging from a single nucleotide to several hundred base pairs [11]. In tea plants, 255,218 InDels were identified with an average density of 84.5 InDels per megabase [11]. The length distribution of InDels typically shows a strong bias toward shorter variants, with mononucleotide InDels being the most abundant type (44.27% of all InDels in tea plants) [11]. The number of InDels generally decreases as length increases, with variants shorter than 20 bp accounting for over 95.5% of all InDels in tea plants [11].

Like SNPs, the functional consequences of InDels depend on their genomic context. InDels located within coding regions can cause frameshift mutations if their length is not a multiple of three, potentially leading to premature stop codons and truncated proteins. Those in regulatory regions may affect gene expression by altering transcription factor binding sites or other regulatory elements. InDels in non-functional regions typically have minimal phenotypic impact. In tea plants, only 12% (31,130) of InDels were located in genic regions, with the majority residing in intergenic regions [11]. Despite their relatively low frequency in genic regions, InDels have proven to be valuable molecular markers due to their stability, reproducibility, and transferability between populations [11].

Table 2: Characteristics and Distribution of InDels in Plant Genomes

| Characteristic | Pattern/Observation | Example from Tea Plant | Functional Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Length Distribution | Decreases with increasing length | 1-20 bp: 95.5% of all InDels [11] | Shorter InDels more common; longer ones rare |

| Most Abundant Type | Mononucleotide InDels | 44.27% (112,976) of total [11] | Simple sequence repeats as mutation hotspots |

| Genomic Location | Predominantly intergenic | 88% in intergenic regions [11] | Majority likely neutral |

| Minority in genic regions | 12% (31,130) in genic regions [11] | Potential impact on gene function | |

| Density | Lower than SNPs | 84.5 InDels/Mb vs. 2341 SNPs/Mb [11] | Less frequent than SNPs but still abundant |

Presence-Absence Variations (PAVs)

PAVs represent an extreme form of structural variation where specific genomic segments containing one or more genes are present in some individuals but entirely absent in others [13]. These variations have gained increasing recognition for their significant role in shaping phenotypic diversity and contributing to reproductive isolation in plants. PAVs are particularly common in genes associated with stress responses and disease resistance, suggesting they may represent an evolutionary adaptation mechanism for rapid environmental adaptation [13].

A compelling example of PAVs with profound phenotypic consequences comes from research on rice subspecies. A PAV at the Se locus functions as a reproductive barrier between indica and japonica rice subspecies by causing hybrid sterility [13]. This locus contains two adjacent genes, ORF3 and ORF4, that exhibit complementary effects. ORF3 encodes a sporophytic pollen killer, while ORF4 protects pollen in a gametophytic manner [13]. In F1 hybrids of indica-japonica crosses, pollen with the japonica haplotype (lacking the protective ORF4 sequence) is aborted due to the pollen-killing effect of ORF3 from indica [13]. This mechanism represents a sophisticated genetic barrier that maintains subspecies identity and demonstrates how PAVs can directly influence reproductive compatibility and evolutionary trajectories.

The functional significance of PAVs extends beyond reproductive barriers. Pangenome analyses across multiple crop species consistently reveal that PAVs are enriched for genes involved in abiotic stress response and disease resistance [13]. This pattern suggests that PAVs contribute to environmental adaptation by creating variation in gene content that can be selectively advantageous under specific conditions. Additionally, fixation of complementary PAVs is believed to contribute to heterosis in hybrid breeding programs, highlighting their practical importance in crop improvement [13].

Methodologies for Genetic Variation Analysis

Detection and Genotyping Techniques

The detection and analysis of genetic variations have evolved substantially with advances in molecular technologies. Early techniques such as restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLPs) and PCR-based markers including random amplification of polymorphic DNA (RAPD), amplified fragment length polymorphisms (AFLPs), and simple sequence repeats (SSRs) have been largely supplanted by high-throughput sequencing approaches that enable comprehensive genome-wide variant discovery [12].

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies have revolutionized plant genetic studies by allowing rapid and cost-effective discovery of thousands to millions of genetic variants [10] [12]. These technologies include platforms such as Illumina sequencing, which generates short reads at high coverage, and third-generation sequencing like PacBio SMRT sequencing, which produces longer reads that are particularly valuable for resolving complex genomic regions [11]. For SNP discovery in complex plant genomes, several strategies have been developed:

- Transcriptome sequencing: Focuses on coding regions by sequencing mRNA, effectively avoiding repetitive regions of the genome [12].

- Reduced-representation sequencing: Techniques like restriction site-associated DNA sequencing (RAD-Seq) and genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS) use restriction enzymes to reduce genome complexity, providing a cost-effective approach for genome-wide variant discovery [12].

- Sequence capture methods: Technologies such as NimbleGen sequence capture and Agilent SureSelect use hybridization probes to enrich specific genomic regions before sequencing, enabling targeted resequencing of genes or regulatory elements [12].

Each method has distinct advantages and limitations depending on the research objectives, genome complexity, and available resources. For instance, transcriptome sequencing is efficient for identifying potentially functional variants in coding regions but misses regulatory elements, while whole-genome sequencing provides comprehensive coverage but requires more extensive sequencing and computational resources [12].

Quantitative Trait Loci (QTL) Mapping and Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS)

QTL mapping and GWAS are powerful statistical approaches that link genetic variations with phenotypic traits. QTL analysis connects phenotypic data (trait measurements) with genotypic data (molecular markers) to explain the genetic basis of variation in complex traits [14]. This method typically involves crossing strains that differ genetically for the trait of interest, then scoring phenotypes and genotypes in the derived population to identify chromosomal regions where markers segregate with trait values [14]. Recent extensions of QTL mapping include expression QTL (eQTL) analysis, which links genetic variations to differences in gene expression, and protein QTL (pQTL) mapping, which associates genetic variants with variations in protein abundance [14].

GWAS represents a complementary approach that uses samples from natural populations and cultivars to identify associations between genetic variants and traits [15]. Standard GWAS tests associations between individual SNPs and a single phenotype, but this simple model often fails to capture complex genetic architectures. Advanced GWAS models have been developed to address these limitations, including:

- Multiple-trait mixed models (MTMM): These models analyze multiple phenotypes simultaneously, increasing statistical power by directly modeling correlation structures between traits [15].

- Environmental interaction models: These approaches incorporate environmental data to understand genotype-by-environment interactions, which is crucial for predicting adaptive responses [15].

- Multivariate Adaptive Shrinkage (MASH): This method addresses computational challenges in high-dimensional data by breaking analysis into stages, first estimating SNP effects on each trait separately then updating these estimates based on standard errors and correlations between traits [15].

These advanced methods provide more realistic modeling of complex genetic architectures and have demonstrated improved power for identifying genetic determinants of complex traits in plants [15].

Experimental Validation of Causal Relationships

Identifying statistical associations between genetic variants and phenotypes is only the first step; establishing causal relationships requires rigorous experimental validation. Several approaches are commonly employed:

- Functional complementation: Introducing wild-type complementary DNA into a mutant background to rescue a loss-of-function mutation or produce an alternative phenotype [14].

- Targeted gene replacement: Precisely modifying specific genomic regions to confirm their role in trait variation [14].

- Reciprocal transplant experiments: Assessing genotype performance across different environments to validate adaptive significance [16].

- Common garden experiments: Growing different genotypes in a uniform environment to isolate genetic effects from environmental influences [16].

These validation approaches are essential for moving beyond correlation to establish causation in genotype-phenotype relationships. For instance, in the study of jasmonate defense hormones in wild tobacco, experimental manipulation of LOX3 gene expression in mesocosm populations provided direct evidence for its role in structuring herbivore communities and altering plant performance [17].

Functional Impacts and Phenotypic Consequences

Gene Function and Regulation

Genetic variations influence plant phenotypes through diverse molecular mechanisms. SNPs in coding regions can alter protein function by changing amino acid sequences, potentially affecting enzyme activity, protein stability, or interaction partners [10]. For example, non-synonymous SNPs in catechin/caffeine biosynthesis-related genes in tea plants were associated with significant differences in catechin and caffeine content, suggesting a direct functional impact on these economically important compounds [11].

Variations in regulatory regions can influence gene expression by modifying transcription factor binding sites, promoter activity, or enhancer elements [12]. Such regulatory changes can have profound phenotypic effects even when coding sequences remain intact. Additionally, structural variations like PAVs can directly determine whether a gene is present or absent in a particular genotype, creating fundamental differences in genetic potential between individuals [13]. The rice Se locus exemplifies how PAVs can create reproductive barriers through complementary gene action, where the presence of a pollen-killer gene in one subspecies and the absence of a protective gene in another leads to hybrid sterility [13].

Defense Responses and Herbivore Communities

Genetic variations in defense-related genes can significantly influence plant interactions with herbivores and shape broader ecological communities. Research on wild tobacco (Nicotiana attenuata) demonstrated that variation in a single key biosynthetic gene in the jasmonate (JA) defense hormone pathway (lipoxygenase 3, LOX3) structured herbivore communities and altered plant performance [17]. JA-deficient plants (silenced in LOX3 expression) were preferentially attacked by the generalist leafhopper Empoasca sp., while the specialist Tupiocoris notatus mirids avoided Empoasca-damaged plants [17].

In experimental mesocosm populations containing both wild-type and JA-deficient plants, the herbivore damage patterns and resulting plant fitness outcomes differed significantly from monocultures [17]. Seed capsule production remained similar for both genotypes in mixed populations but differed in monocultures, with the specific outcomes depending on caterpillar density [17]. This demonstrates how genetic variation in a single defense gene can create ripple effects through ecological communities and influence plant reproductive success in complex ways dependent on population composition and herbivore density.

Reproductive Isolation and Speciation

Genetic variations play a crucial role in reproductive isolation and speciation processes in plants. The PAV at the rice Se locus contributes to reproductive isolation between indica and japonica subspecies by causing hybrid sterility [13]. This two-gene system operates through a sophisticated mechanism where ORF3 acts as a sporophytic pollen killer and ORF4 provides gametophytic protection [13]. In hybrids, pollen lacking the protective ORF4 (from japonica) is killed by the ORF3 pollen killer (from indica), leading to selective abortion and partial sterility [13].

Evolutionary analysis suggests that this PAV system has contributed significantly to the reproductive isolation between the two rice subspecies and supports the hypothesis of independent domestication of indica and japonica from different O. rufipogon populations [13]. This example illustrates how structural variations can create genetic barriers that maintain species or subspecies identity and influence evolutionary trajectories.

Table 3: Experimental Approaches for Validating Genetic Variants

| Method | Principle | Application Example | Key Outcome Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Complementation | Introduce wild-type gene to rescue mutant phenotype | Complementing defense gene mutations in tobacco [17] | Restoration of wild-type phenotype (e.g., herbivore resistance) |

| Reciprocal Transplant | Grow genotypes across multiple environments | Testing local adaptation in natural populations [16] | Fitness measures (survival, reproduction) across environments |

| Common Garden | Grow diverse genotypes in uniform environment | Comparing defensive traits in plant populations [16] | Phenotypic variation under controlled conditions |

| Gene Silencing/Editing | Reduce or eliminate gene function | LOX3 silencing in tobacco [17] | Altered phenotype (e.g., changed herbivore preference) |

| Hybridization Analysis | Cross divergent genotypes | indica × japonica rice crosses [13] | Hybrid fertility/viability, trait segregation |

Research Reagent Solutions and Technical Tools

Modern plant genetics research relies on a diverse toolkit of reagents, platforms, and technical solutions for analyzing genetic variations. The following table summarizes key resources mentioned across the surveyed literature:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Technical Solutions for Genetic Variation Analysis

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Application | Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina, PacBio, Ion Torrent | High-throughput DNA/RNA sequencing | Tea plant genome sequencing [11] |

| Genotyping Arrays | SNP chips, microarrays | Parallel genotyping of thousands of markers | Human SNP chips adapted for plants [10] |

| Variant Discovery Tools | GATK, SAMtools, HaploSNPer | Bioinformatics pipelines for variant calling | Polyploid SNP validation [12] |

| Complexity Reduction | Restriction enzymes (ApeKI) | Reduce genome complexity for sequencing | Restriction Site Associated DNA (RAD) [12] |

| Target Enrichment | NimbleGen, SureSelect | Capture specific genomic regions | Exome sequencing in plants [12] |

| Genetic Mapping | R/qtl, LIMIX, GEMMA | QTL mapping and association analysis | Multiple-trait GWAS [15] |

| Validation Reagents | PCR primers, sequencing primers | Confirm genetic variants | InDel marker development in tea [11] |

| Functional Validation | RNAi constructs, CRISPR-Cas9 | Gene manipulation for functional tests | LOX3 silencing in tobacco [17] |

The spectrum of genetic variations—from single nucleotide changes to presence-absence polymorphisms—forms the fundamental basis for phenotypic diversity in plants. SNPs provide the highest density of genomic markers and contribute to both coding and regulatory variations, while InDels offer stable, reproducible markers distributed throughout plant genomes. PAVs represent the most dramatic form of genetic variation, with the potential to create fundamental differences in gene content between individuals and drive reproductive isolation.

Advanced genomic technologies have dramatically accelerated our ability to discover and characterize these variations, while sophisticated statistical methods like multi-trait GWAS and QTL mapping enable researchers to connect genetic variants with complex phenotypic traits. However, establishing causal relationships requires rigorous experimental validation through complementary approaches including functional complementation, gene editing, and ecological experiments.

Understanding these genetic variations and their functional consequences has profound implications for both basic plant biology and applied crop improvement. As research continues to unravel the complex relationships between genetic variations and phenotypic outcomes, this knowledge will increasingly empower efforts to develop resilient, productive crop varieties through molecular breeding and genomic selection strategies. The integration of multiple approaches—from high-throughput sequencing to field-based phenotypic assessments—will be essential for fully elucidating the intricate pathways connecting plant genotypes to their phenotypic expressions.

The Critical Role of Environment (GxE Interaction) in Phenotypic Expression

The relationship between genotype and phenotype is a cornerstone of genetics, yet it is not a simple one-to-one correlation. Genotype-by-Environment (GxE) interaction describes the phenomenon wherein the effect of a genotype on the phenotype depends on the specific environmental conditions. In plant research, understanding GxE is crucial for bridging the gap between genetic potential and realized agricultural output, as it significantly influences the selection and recommendation of cultivars [18]. The performance and productivity of crops are determined by a complex interplay of genetic factors (G), environmental conditions (E), and their interaction (GEI), which can complicate breeding efforts aimed at developing stable, high-yielding varieties [18] [19]. When significant GxE exists, a genotype superior in one environment may perform poorly in another, a phenomenon known as crossover interaction [19]. Deciphering the genetic basis of complex traits therefore requires an understanding of GxE to link physiological functions and agronomic traits to genetic markers [20]. This guide provides a technical overview of the concepts, analytical methods, and applications of GxE research in plant sciences.

Fundamental Concepts and Statistical Frameworks

Defining GxE and Mega-Environments

In plant breeding, a "mega-environment" (ME) is defined as a group of locations sharing similar environmental conditions where a specific genotype or set of genotypes consistently demonstrates superior performance [18]. The concept of MEs allows breeders to address repeatable GxE by developing genotypes tailored to specific environmental niches, while non-repeatable GxE can be managed through targeted selection within an ME [18].

Analytical Models for GxE Dissection

Several statistical models are employed to partition phenotypic variance and understand the structure of GxE. Key models include:

- Analysis of Variance (ANOVA): This foundational method decomposes the total phenotypic variance into components attributable to genotype (G), environment (E), and their interaction (GxE). While ANOVA indicates the presence and significance of GxE, it does not elucidate its patterns.

- Additive Main Effects and Multiplicative Interaction (AMMI): The AMMI model combines standard ANOVA for main effects with Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to decompose the GxE interaction into Interaction Principal Component Axes (IPCA) [19]. This hybrid model provides a more nuanced understanding of interaction patterns, helping to identify genotypes with specific adaptation.

- Genotype + Genotype-by-Environment Interaction (GGE) Biplot: The GGE biplot model visualizes the genotype (G) effect and the GxE interaction jointly [21]. It is particularly powerful for identifying mega-environments ("which-won-where" patterns), evaluating test environments for their discriminative power and representativeness, and visually ranking genotypes based on both performance and stability [18] [21].

- Linear Mixed-Effects Models and BLUP: Models utilizing Best Linear Unbiased Prediction (BLUP) and stability metrics like the Weighted Average Absolute Scores of BLUPs (WAASB) improve predictive accuracy by treating genetic and environmental effects as random, offering a robust framework for assessing performance and stability simultaneously [18].

Table 1: Key Statistical Models for GxE Analysis

| Model | Key Function | Primary Outputs | Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| ANOVA | Variance partitioning | Significance of G, E, and GxE effects | Simple, foundational test for interaction |

| AMMI | Decompose GxE pattern | Interaction Principal Component Axes (IPCAs) | Combines additive and multiplicative models; detailed interaction insights |

| GGE Biplot | Visualize G + GxE | "Which-won-where" view; mean vs. stability view | Ideal for mega-environment analysis and genotype evaluation [21] |

| Mixed Models (BLUP) | Prediction & Stability | WAASB index; Estimated Breeding Values (EBVs) | Handles complex experimental designs; high predictive accuracy |

Quantitative GxE Analysis in Multi-Environment Trials

Multi-Environment Trials (METs) are the standard approach for evaluating GxE. The following case studies illustrate the quantitative outcomes of such analyses.

Case Study 1: Winter Wheat in North China

A large-scale MET with 71 winter wheat genotypes across 16 locations over five years in the North China Plain revealed highly significant effects of environment (E), genotype (G), and GxE [18]. The analysis of variance demonstrated that the environment was the largest source of variation, with GxE variance exceeding the variance from genotypic effects alone. The AMMI model showed that the first three IPCAs captured over 70% of the GxE variance [18]. Environmental covariates were critical for interpretation; grain yield was positively correlated with vapor pressure deficit and sunshine duration, but negatively correlated with relative humidity and total precipitation [18]. Key environmental drivers of yield variation included minimum temperature and clay content.

Table 2: Superior Winter Wheat Genotypes Identified by GGE Biplot Analysis (North China Plain) [18]

| Year | Superior Genotypes |

|---|---|

| 2014 | JM196, WN4176, HN6119 |

| 2015 | ZX4899, H9966, LM22 |

| 2016 | BM7, KN8162, KM3 |

| 2017 | HH14-4019, HM15-1, HH1603 |

| 2018 | S14-6111, JM5172 |

Case Study 2: Open-Pollinated Tomato in the Kashmir Himalaya

An evaluation of 16 tomato genotypes across six locations showed that environment (E), genotype (G), and GxE were all highly significant (p < 0.001) for yield per hectare [19]. Environment alone contributed 47.5% of the total phenotypic variation, again highlighting its dominant role. Using the AMMI model and stability indices (WAAS and MTSI), researchers identified Arka Meghali as the highest-yielding variety and NDF-9 as a genotype with remarkable adaptability across the diverse test environments of the Kashmir Valley [19].

Case Study 3: Cowpea in Egypt

A study of ten cowpea genotypes across nine environments (three locations over three seasons) also found significant (p < 0.01) effects for G, E, and GxE on fresh yield [21]. The environment was again the most influential factor, accounting for 86.15% of the total sum of squares, with G and GxE contributing 6.54% and 4.54%, respectively [21]. The AMMI analysis revealed that the first five principal components were significant, with PC1 and PC2 explaining 40.02% and 23.61% of the GxE variation, respectively. Genotype G3 had the highest mean yield, while genotype G7 was identified as the most stable across the nine environments [21].

Table 3: Summary of Variance Components from GxE Case Studies

| Crop (Study) | Variance Contribution (E) | Variance Contribution (G) | Variance Contribution (GxE) | Key Stable/High-Yielding Genotypes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Winter Wheat [18] | Largest source | Less than GxE | Exceeded G variance | JM196, ZX4899, BM7, HH14-4019, S14-6111 |

| Tomato [19] | 47.5% | Significant (p<0.001) | Significant (p<0.001) | Arka Meghali (yield), NDF-9 (adaptability) |

| Cowpea [21] | 86.15% | 6.54% | 4.54% | G3 (yield), G7 (stability) |

Advanced Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

High-Dimensional Environmental Covariates and Envirotyping

Modern GxE analysis moves beyond labeling environments by location and year. Envirotyping uses high-dimensional environmental data, such as meteorological parameters and soil physicochemical properties, to model crop growth in specific conditions [18] [22]. For example, a study in pigs utilized eight daily environmental covariates (ECs)—including temperature, relative humidity, and wind speed—retrieved from the NASA POWER database for 100 days preceding trait measurement to characterize the environment for each animal [22]. The environmental similarity kernel (K~E~) is computed from an envirotype-covariable matrix (W) using the formula: $$K_E = \frac{WW'}{trace(WW')} nrow(W)$$ This kernel quantifies environmental similarity and can be used in genomic models to correlate environments and model GxE more accurately [18] [22].

Genomic Approaches to GxE

Genomic tools allow researchers to dissect the genetic architecture of GxE.

- Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS): These studies can be extended to detect marker-trait associations that are sensitive to environmental changes, known as GxE QTLs. For instance, a potato study identified 77 marker-trait associations for Nitrogen Use Efficiency (NUE) and related traits, with multi-trait genomic regions found on specific chromosomes [20]. Some QTLs are constitutive (stable across environments), while others are adaptive (identified only in specific environments) [20].

- Polygenic Risk Score (PRS) by Environment Interaction (PRSxE): This method aggregates genome-wide effects into a single score in a discovery sample and tests for its interaction with an environmental moderator in a target sample. While powerful for detecting broad genetic effects, its accuracy depends on the statistical power of the discovery GWAS [23].

- Reaction Norm Models: These models describe the phenotypic response of a genotype as a function of an environmental gradient, allowing for the prediction of performance under unobserved environmental conditions.

Diagram 1: GxE Analysis Workflow. This flowchart outlines the key stages of a comprehensive Genotype-by-Environment interaction study, from data collection to final analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for GxE Experiments

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Plant Genetic Panel | Core germplasm for evaluating genetic effects. | A diverse panel of genotypes (e.g., 71 wheat [18], 16 tomato [19], 10 cowpea [21]) is essential. |

| Environmental Covariates (ECs) | Quantifying the "E" in GxE. | Includes meteorological (Tmin, Tmax, RH, rainfall) [18] and soil data (clay content, water holding capacity) [18]. Sourced from weather stations or NASA POWER [22]. |

| Genotyping Platform | Genome-wide marker data for genomic analysis. | SNP arrays for constructing genomic relationship matrices [22] or conducting GWASpoly for polyploids [20]. |

| Statistical Software (R/packages) | Data analysis and visualization. | R packages such as {metan} [19], {EnvRtype} [18], GWASpoly [20], and OpenMx [23] are critical. |

| Field Trial Infrastructure | Conducting Multi-Environment Trials (METs). | Requires multiple, geographically dispersed locations [18] [19] following a Randomized Complete Block Design (RCBD) with replications. |

| Estrogen receptor antagonist 7 | Estrogen Receptor Antagonist 7 | Explore Estrogen Receptor Antagonist 7, a potent research compound for breast cancer studies. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human use. |

| 1-Adamantane-amide-C7-NH2 | 1-Adamantane-amide-C7-NH2, MF:C19H34N2O, MW:306.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The critical role of GxE in phenotypic expression is undeniable. For plant researchers, successfully navigating the path from genotype to phenotype requires a sophisticated integration of robust METs, advanced statistical models like AMMI and GGE, and modern genomic tools. The emergence of envirotyping—the use of high-dimensional environmental data to characterize growing conditions—represents a significant leap forward, enabling a more precise and predictive understanding of how genotypes respond to environmental cues [18] [22]. By systematically employing these methodologies, breeders can make informed decisions, selecting genotypes that combine high yield with stability, thereby accelerating the development of resilient cultivars suited to specific mega-environments and contributing to global food security in the face of climate variability.

The relationship between an organism's genotype and its observable characteristics, or phenotype, represents one of the most fundamental aspects of genetics. Despite a century of research, predicting trait outcomes from genetic information remains challenging due to two pervasive biological phenomena: epistasis (interactions between genes) and genetic redundancy (functional overlap between genes) [24]. These phenomena create substantial obstacles for plant researchers seeking to understand the genetic architecture of complex traits, from agricultural yield to stress resilience.

Epistasis was first identified by William Bateson over 100 years ago through observations that specific gene combinations could produce unexpected phenotypic outcomes in dihybrid crosses [24]. The concept has since expanded to encompass various forms of gene interactions, all sharing the common feature that the effect of a genetic variant depends on the genetic background in which it occurs [24] [25]. Similarly, genetic redundancy, often arising from gene duplication events, creates buffered systems where the effect of a mutation in one gene may only become apparent when combined with mutations in redundant partners [26].

In plant research, understanding these phenomena is crucial for bridging the gap between genomic information and phenotypic expression. This technical guide examines the current state of knowledge regarding epistasis and genetic redundancy, with particular emphasis on their implications for predicting trait outcomes in plant systems.

Theoretical Framework: Defining Epistasis and Its Biological Significance

Conceptual Models of Gene Interaction

Epistasis manifests in several distinct forms, each with different implications for predicting trait outcomes:

Compositional Epistasis: This traditional form describes scenarios where an allele at one locus masks or suppresses the effect of an allele at another locus. The only way to observe this effect is through combinatorial substitution of alleles against a standard genetic background [24].

Statistical Epistasis: Developed by R.A. Fisher, this population-level concept measures deviations from additivity when alleles at different loci are combined, averaged across all genetic backgrounds present in a population [24].

Functional Epistasis: This refers to the molecular interactions that proteins and other genetic elements have with one another, whether they operate within the same pathway or form physical complexes [24].

Each perspective offers different insights into how genetic interactions shape phenotypic outcomes, with compositional and statistical epistasis being most relevant for quantitative genetic studies in plants.

Genetic Redundancy as a Form of Epistasis

Genetic redundancy represents a special case of epistasis where paralogous genes (arising from gene duplication events) perform overlapping functions, creating buffered systems that canalize developmental processes [26]. In these systems, single mutations may show minimal effects, while combinations reveal strong synergistic interactions. For example, in tomato, the JOINTLESS2 (J2) and ENHANCER OF JOINTLESS2 (EJ2) genes function redundantly to control inflorescence architecture, with single mutants showing cryptic phenotypes while double mutants exhibit dramatic branching increases [26].

Table 1: Types of Epistasis and Their Characteristics in Plant Systems

| Type of Epistasis | Definition | Detection Method | Implication for Trait Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compositional | One allele masks the effect of another allele | Dihybrid crosses with constructed genotypes | Predictions require specific genetic context |

| Statistical | Deviation from additive combination of alleles | Population-level analysis of variance | Population-specific predictions |

| Functional | Molecular interactions between gene products | Protein-protein interaction studies | Requires understanding of molecular pathways |

| Redundancy | Overlapping function between paralogous genes | Multiple mutant analysis | Single mutants underestimate gene function |

Current Research Paradigms and Key Findings

Hierarchical Epistasis in Plant Development

Recent research in tomato inflorescence development has revealed that epistatic interactions can operate hierarchically, with different layers of interaction either enhancing or diminishing phenotypic effects [26]. In the J2-EJ2 regulatory network, researchers observed:

- A layer of dose-dependent interactions within paralogue pairs that enhanced branching

- A layer of antagonism between paralogue pairs, where accumulating mutations in one pair progressively diminished the effects of mutations in the other

This hierarchical structure demonstrates how regulatory network architecture and complex dosage effects from paralogue diversification converge to shape phenotypic space, producing the potential for both strongly buffered phenotypes and sudden bursts of phenotypic change [26].

Cryptic Genetic Variation as an Evolutionary Reservoir

Cryptic genetic variants exert minimal phenotypic effects alone but form a vast reservoir of genetic diversity that can drive trait evolvability through epistatic interactions [26]. These hidden variants most likely accumulate in buffered molecular contexts, such as redundancy within gene families and gene regulatory networks. Under this hypothesis, epistatic interactions between previously cryptic alleles may result in the sudden appearance of phenotypic variation in previously invariant traits, facilitating both within-species adaptation and macroevolutionary transitions [26].

Table 2: Quantitative Evidence for Epistasis in Plant Systems

| Study System | Genetic Elements | Phenotypic Effect | Statistical Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tomato Inflorescence [26] | J2, EJ2, PLT3, PLT7 | Inflorescence branching | 216 genotypes, >35,000 inflorescences quantified |

| Maize Root Architecture [27] | DRO1, Rt1, ZmCIPK15 | Root system architecture | >1700 root crowns, multivariate GWAS |

| Arabidopsis Flowering Time [28] | DOG1, VIN3 | Flowering time traits | 1135 accessions, machine learning models |

The Infinitesimal Model in the Presence of Epistasis

Remarkably, despite the prevalence of epistasis, quantitative genetics often operates effectively under the infinitesimal model, which assumes that genetic values remain normally distributed with constant variance components, even under selection [29]. This model can hold even with substantial epistasis because phenotypes occupy a narrow range relative to the range of multilocus genotypes possible given standing variation [29]. The key insight is that knowing the trait value provides little information about individual genotypes when very many loci influence the trait, meaning that selection hardly perturbs the variance components away from their neutral evolution.

Methodological Approaches for Detecting Epistasis

Experimental Designs for Uncovering Genetic Interactions

Systematic Mutant Combination

The most direct approach for detecting epistasis involves creating multiple mutant combinations through crosses or genome editing. In the tomato inflorescence study, researchers generated 216 genotypes combining coding mutations with cis-regulatory alleles across four network genes, enabling quantification of branching in over 35,000 inflorescences to map hierarchical epistasis [26]. This high-resolution genotype-phenotype mapping required:

- Identification of network components through analysis of pan-genome variation

- Engineered promoter alleles using CRISPR/Cas9 to test specific regulatory regions

- Quantification of phenotypic effects across a wide spectrum of genetic combinations

High-Throughput Phenotyping Technologies

Advanced phenotyping platforms are essential for capturing the complex phenotypic outcomes resulting from epistatic interactions:

- 3D root modeling using X-ray computed tomography provides detailed insights into root system architecture [27]

- Multi-view imaging enhances traditional 2D phenotyping by capturing more comprehensive phenotypic information [27]

- Multivariate trait analysis effectively dissects complex phenotypes and identifies pleiotropic quantitative trait loci [27]

Computational and Statistical Methods

Genomic Prediction Models

Traditional genomic selection approaches like Genomic Best Linear Unbiased Prediction (GBLUP) primarily capture additive genetic effects, but extensions can incorporate epistasis:

- EG-BLUP includes all pairwise SNP interactions but may introduce noise from unimportant variables [30]

- sERRBLUP (selective Epistatic Random Regression BLUP) incorporates only a selected subset of pairwise SNP interactions with the highest effect variances, significantly improving predictive ability compared to standard GBLUP [30]

- Bivariate models that simultaneously analyze multiple traits or environments consistently outperform univariate models in predictive ability [30]

Machine Learning and Explainable AI

Machine learning approaches offer promising alternatives for capturing complex genetic interactions:

- Random Forests and Gradient Boosting (XGBoost, CatBoost) can capture non-additive genetic architectures [28]

- Explainable AI (XAI) techniques, particularly SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations), provide interpretability by identifying SNPs that contribute most to trait prediction [28]

- Neural network frameworks like G-P Atlas use a two-tiered denoising autoencoder approach to simultaneously model multiple phenotypes and capture nonlinear relationships between genes [9]

Table 3: Computational Methods for Modeling Epistasis

| Method | Approach | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| GBLUP/EG-BLUP [30] | Genomic relationship matrices | Robust, widely implemented | Primarily additive effects |

| sERRBLUP [30] | Selected pairwise interactions | Increased predictive accuracy | Computational complexity |

| Machine Learning [28] | Non-linear algorithms | Captures complex interactions | Interpretability challenges |

| G-P Atlas [9] | Neural network autoencoder | Multi-phenotype modeling | Data requirements |

Case Study: Hierarchical Epistasis in Tomato Inflorescence Development

Experimental Workflow and Protocol

A comprehensive study of tomato inflorescence architecture provides a detailed protocol for analyzing epistasis in plant systems [26]:

Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Epistasis Studies in Plants

| Reagent/Resource | Function in Experimental Design | Application in Tomato Study [26] |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas9 system | Genome editing for allele generation | Created promoter deletions and SNVs in EJ2 |

| Pan-genome data | Identification of natural variation | Mined for EJ2 promoter variants in wild species |

| Introgression lines | Testing natural alleles in isogenic backgrounds | Evaluated EJ2Sh and EJ2Sp variants |

| Expression atlas | Identify co-expressed regulators | Found PLT3 and PLT7 expression patterns |

| Promoter-reporter constructs | Validate regulatory interactions | Tested PLT binding to EJ2 promoter |

Implications for Plant Breeding and Biotechnology

Challenges in Genomic Selection

The presence of epistasis creates significant challenges for genomic prediction in plant breeding:

- Models accounting for all pairwise SNP interactions (ERRBLUP) do not necessarily outperform additive models (GBLUP) in predictive ability [30]

- However, selecting only the top-ranked pairwise interactions (sERRBLUP) can increase predictive ability by 5.9-112.4% in univariate models and up to 27.9% in bivariate models compared to standard GBLUP [30]

- The benefit of including epistatic effects depends on genetic architecture, with traits influenced by strong interactions showing the greatest improvement [30]

Evolutionary Consequences and Crop Adaptation

Epistasis plays a crucial role in evolutionary processes relevant to crop adaptation:

- Diminishing-returns epistasis, where beneficial mutations have smaller effects in fitter genetic backgrounds, is commonly observed in microbial evolution and may explain declining adaptability in evolving populations [25]

- Increasing-costs epistasis, where deleterious mutations become more harmful in fitter backgrounds, can reduce mutational robustness during adaptation [25]

- Cryptic genetic variation accumulated in redundant gene networks can fuel sudden phenotypic changes when environmental conditions or genetic backgrounds shift [26]

Future Directions and Concluding Perspectives

Despite significant advances, predicting trait outcomes in the face of epistasis and genetic redundancy remains challenging. Future research directions should focus on:

- Developing more sophisticated models that can capture higher-order interactions without being overwhelmed by computational complexity

- Integrating multi-omics data to understand the molecular mechanisms underlying epistatic interactions

- Expanding studies across diverse plant species to determine general principles of gene interaction

- Leveraging machine learning approaches that balance predictive power with biological interpretability

The hierarchical nature of epistasis revealed in recent plant studies suggests that gene interactions follow structured patterns rather than random complexity [26]. This structure provides hope that with appropriate experimental designs and analytical frameworks, researchers can eventually navigate the challenges posed by epistasis and genetic redundancy to accurately predict trait outcomes from genetic information.

As these fields advance, they will undoubtedly transform plant breeding from a largely empirical practice to a predictive science, enabling more rapid development of crop varieties with enhanced yield, resilience, and adaptation to changing environments.

Historical and Conceptual Foundations of Genomic Selection in Plants

Genomic Selection (GS) represents a paradigm shift in plant breeding, transitioning from traditional phenotype-based selection to genotype-led strategies. This approach utilizes genome-wide molecular markers to predict the genetic merit of breeding candidates, thereby accelerating the development of improved crop varieties. GS was conceived to address a critical limitation in plant improvement: the inefficiency of conventional breeding for complex, polygenic traits. Where traditional methods rely on visual selection and Marker-Assisted Selection (MAS) can only handle a limited number of large-effect genes, GS enables breeders to capture the complete genetic architecture of quantitative traits, including contributions from numerous small-effect loci [31] [32]. This technical guide explores the historical context, methodological framework, and practical implementation of GS, positioning it within the broader scientific inquiry into genotype-to-phenotype relationships in plants.

Historical Evolution from Phenotypic to Genomic Selection

Limitations of Conventional Breeding and Marker-Assisted Selection

Traditional plant breeding relies on phenotypic selection (PS), where breeders select individuals based on observable traits. This approach presents significant constraints: it is time-consuming (often requiring 12-15 years to release a new variety), strongly influenced by environmental conditions, and particularly ineffective for complex traits with low heritability [33] [31]. The introduction of molecular markers offered initial promise for improving selection efficiency through Marker-Assisted Selection (MAS). However, MAS proved primarily suitable for traits controlled by one or few major genes, as it relies on identifying significant marker-trait associations prior to selection [32].

For quantitative traits governed by many genes with minor effects (such as yield, abiotic stress tolerance, and quality parameters), MAS demonstrated critical limitations. Conventional QTL mapping and association studies often failed to detect loci with small effects, potentially missing a substantial portion of genetic variation [31]. When numerous loci influence a trait, estimating individual effects becomes statistically challenging, and MAS—which typically incorporates only significant markers—captures only a fraction of the total genetic merit [32].

Table 1: Comparison of Plant Breeding Approaches

| Breeding Method | Genetic Basis | Selection Basis | Timeframe for Variety Release | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Breeding | Phenotypic expression | Visual trait assessment | 12-15 years | Environmental influence, slow progress for complex traits |

| Marker-Assisted Selection (MAS) | Few major-effect genes/QTLs | Significant marker-trait associations | 5-8 years | Ineffective for polygenic traits, misses minor-effect QTLs |

| Genomic Selection | Genome-wide markers (major + minor effects) | Genomic Estimated Breeding Value (GEBV) | 2-5 years | High initial genotyping costs, computational complexity |

The Genomic Selection Paradigm

Genomic Selection emerged as a transformative solution to the challenges of MAS for complex traits. Proposed initially by Meuwissen, Hayes, and Goddard in 2001, GS employs genome-wide marker coverage to capture both major and minor gene effects simultaneously [32] [34]. The foundational principle of GS is that all markers, regardless of statistical significance, contribute to predicting genetic value. This approach avoids the pre-selection of significant markers, thereby minimizing bias in effect estimation and enabling capture of a more complete representation of the genetic architecture [34].

GS fundamentally changes the selection unit in breeding programs. While phenotypic selection evaluates the line (or individual) based on trait performance, and MAS selects for specific marker alleles, GS uses the Genomic Estimated Breeding Value (GEBV)—a genomic prediction of an individual's breeding value derived from all marker effects across the genome [34]. This shift enables selection early in the breeding cycle, even before phenotypic expression, significantly reducing generation intervals and accelerating genetic gain [31].

Core Methodology of Genomic Selection

Theoretical Framework and Key Concepts

The genomic selection framework rests upon a genetic model that partitions phenotypic variation into genetic and environmental components. The basic genetic model is represented as:

P = G + E

Where:

- P = Phenotypic value

- G = Genotypic value (sum of genetic effects)

- E = Environmental effect [34]

In GS, the genotypic value (G) is approximated using genome-wide markers, resulting in the Genomic Estimated Breeding Value (GEBV). The accuracy of this prediction depends heavily on heritability—the proportion of phenotypic variance attributable to genetic factors. Narrow-sense heritability (h²), which represents the proportion of phenotypic variance due to additive genetic effects, is particularly crucial for GS as it determines the upper limit of prediction accuracy [34].

Table 2: Key Factors Influencing Genomic Selection Accuracy

| Factor | Impact on Prediction Accuracy | Practical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Training Population Size | Positive correlation, with diminishing returns | Optimal size depends on genetic architecture; typically hundreds to thousands of individuals |

| Marker Density | Increases with density until reaching plateau | Dependent on linkage disequilibrium (LD) decay; higher density needed for crops with rapid LD decay |

| Trait Heritability | Higher heritability yields higher accuracy | Low-heritability traits require larger training populations |

| Genetic Relationship | Higher accuracy when training and breeding populations are closely related | Relationship decay over generations necessitates model updating |

| Statistical Model | Varies by genetic architecture | Parametric models best for additive traits; non-parametric for complex architectures |

The Genomic Selection Workflow

The implementation of genomic selection follows a systematic workflow comprising several critical stages:

Figure 1: Genomic Selection Workflow. The process begins with establishing a training population with both genotypic and phenotypic data, which is used to train a prediction model. This model then calculates Genomic Estimated Breeding Values (GEBVs) for the breeding population, informing selection decisions for the next breeding cycle.

Training Population Establishment

The foundation of GS is a training population (TP) consisting of individuals that have been both genotyped (using genome-wide markers) and phenotyped (evaluated for target traits) [31] [32]. The TP should:

- Be sufficiently large (typically hundreds to thousands of individuals)

- Represent the genetic diversity of the breeding population

- Have accurate phenotypic records, preferably from multiple environments

- Share genetic relationships with the selection candidates [35]

The size and composition of the TP significantly impact prediction accuracy. While larger populations generally improve accuracy, there are diminishing returns beyond an optimal size, necessitating careful resource allocation [35].

Statistical Model Training

The core of GS involves developing a statistical model that establishes the relationship between genotype and phenotype in the TP. The basic linear model for GS can be represented as:

y = 1ₙμ + Xβ + ε

Where:

- y = vector of phenotypic observations

- μ = overall mean

- X = design matrix of marker genotypes

- β = vector of marker effects

- ε = vector of residual effects [32]

This model faces the statistical challenge of "large p, small n"—where the number of markers (p) exceeds the number of observations (n). This necessitates specialized statistical methods to avoid overfitting.

GEBV Calculation and Selection

Once the model is trained, it is applied to the breeding population (BP)—individuals that have been genotyped but not phenotyped. The model uses the genotypic data of BP individuals to calculate their Genomic Estimated Breeding Values (GEBVs) [32] [34]. Selection decisions are then based on these GEBVs, with individuals possessing the highest values advanced in the breeding program. This enables selection without extensive phenotyping, dramatically reducing cycle time [31].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Genotyping and Phenotyping Protocols

Genotyping Methods

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) technologies have been instrumental in making GS feasible and cost-effective. Key approaches include:

- Genotyping-by-Sequencing (GBS): A reduced-representation sequencing method that provides high-density SNP coverage without requiring a reference genome [31]

- Array-based SNP genotyping: Platform-specific arrays (e.g., Illumina Infinium) offering standardized, high-throughput genotyping [36]

- Whole-Genome Sequencing: Provides complete genomic information but remains cost-prohibitive for large breeding populations [31]