From Lab to Drug Discovery: How Quantitative Biology is Revolutionizing Plant Science

This article explores the transformative impact of quantitative biology on plant science, a field increasingly critical for drug discovery and biomedical innovation.

From Lab to Drug Discovery: How Quantitative Biology is Revolutionizing Plant Science

Abstract

This article explores the transformative impact of quantitative biology on plant science, a field increasingly critical for drug discovery and biomedical innovation. We first establish the core principles of this interdisciplinary approach, which integrates computational modeling, biophysics, and high-throughput data to understand plant systems. The discussion then progresses to specific methodologies, from AI-driven proteomics to mechanistic mathematical models, and their application in areas like molecular pharming. A practical troubleshooting section addresses common challenges in model adoption and data integration. Finally, the article examines validation frameworks and comparative analyses, showcasing how plant-derived insights and models are being validated and applied in biomedical contexts to advance therapeutic development.

The Quantitative Shift: Core Principles and Revolutionary Potential in Plant Biology

Quantitative plant biology is an interdisciplinary field that builds on a long history of biomathematics and biophysics, revolutionizing how we produce knowledge about plant systems [1]. This approach transcends simple measurement collection, establishing a rigorous framework where quantitative data—whether molecular, geometric, or mechanical—are statistically assessed and integrated across multiple scales [1]. The core of this paradigm is an iterative cycle of measurement, modeling, and experimental validation, where computational models generate testable predictions that guide further experimentation [1]. This formalizes biological questioning, making hypotheses truly testable and interoperable, which is key to understanding plants as complex multiscale systems [1]. By embracing quantitative features such as variability, noise, robustness, delays, and feedback loops, this framework provides a more dynamic understanding of plant inner dynamics and their interactions with the environment [1].

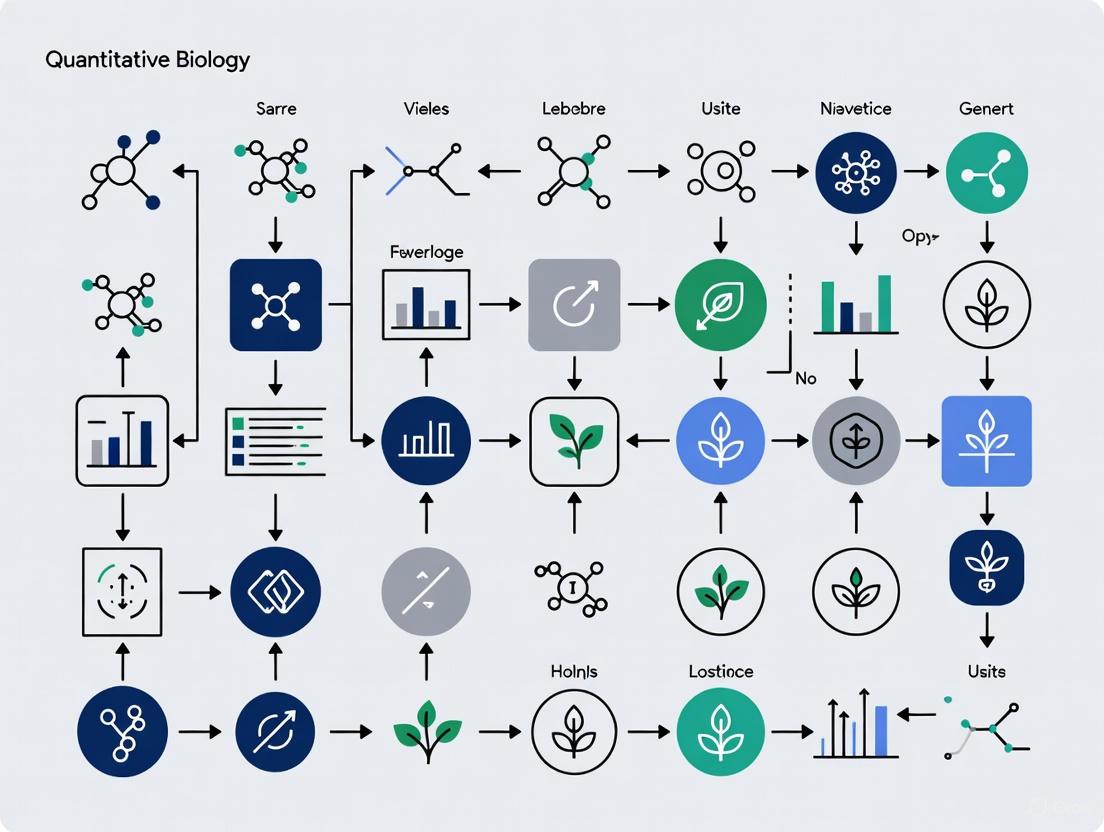

The Core Iterative Cycle of Quantitative Plant Biology

The foundational process in quantitative plant biology is an iterative model identification and refinement cycle. This systematic approach ensures continuous model improvement and more accurate representation of biological reality [2].

The Iterative Model Identification Scheme

The iterative scheme for model identification integrates available system knowledge with experimental measurements in a continuous loop of refinement [2]. The process begins by determining an optimal set of measurements based on parameter identifiability and potential for accurate estimation [2]. The following diagram illustrates this continuous refinement cycle:

Key Components of the Iterative Cycle

Determination of Optimal Measurement Set

The initial critical step involves selecting which biological elements to measure to maximize information gain for model identification. This selection uses the Fisher Information Matrix (FIM) and parameter identifiability analysis to determine the species whose concentration measurements would provide maximum benefit for accurate parameter estimation [2]. The orthogonal method assesses parameter identifiability by analyzing the scaled sensitivity coefficient matrix, identifying parameters that can be reliably estimated from the available measurements [2].

State Regulator Problem (SRP) Formulation

The SRP algorithm uses network connectivity along with partial measurements to estimate all system unknowns, including unmeasured concentrations and reaction rates [2]. Importantly, this step does not utilize kinetic models of reaction rates, instead relying on the biological network structure and stoichiometry to complete the system picture from limited measurements [2].

Parameter Estimation Using Full System Information

With complete estimates of concentrations and reaction rates from SRP, model parameters are estimated [2]. This approach decouples model identification, allowing parameters in each reaction's kinetic equation to be determined independently rather than simultaneously estimating all parameters from limited measurements [2].

Model Validation and Invalidation Testing

This critical "quality control" step compares model predictions with experimental data not used in the SRP algorithm before application [2]. Model invalidity can also be determined when predictions conflict with established biological knowledge [2].

Optimal Experiment Design

When models require refinement, optimal experiment design using parameter identifiability and D-optimality criteria determines which new experiments would generate the most informative data for model improvement in subsequent iterations [2].

Quantitative Approaches to Plant Signaling Networks

Signaling networks process and integrate information from multitude of receptor systems, relaying it to cellular effectors that enact condition-appropriate responses [1]. Quantitative approaches reveal how these networks behave under varying conditions beyond simple binary ("on" vs. "off") descriptions [1].

Temporal Dynamics of Signaling

Unlike traditional approaches that emphasize identification of core pathway components, quantitative biology investigates the temporal dimension of information encoding—how the duration, frequency, and amplitude of signals affect downstream responses [1]. Research in mammalian cells demonstrates that transient activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) through epidermal growth factor can result in cell proliferation, while sustained activation by nerve growth factor leads to cell differentiation [1]. Modulation of feedback strength in inhibitory loops can produce various output states ranging from sustained monotone responses to transient adapted outputs, oscillations, or bi-stable, switch-like responses [1].

Biosensors and Network Perturbation Tools

Breakthroughs in understanding plant signaling increasingly rely on an ever-expanding set of biosensors that enable in vivo visualization and quantification of signaling molecules with cellular or subcellular resolution [1]. These tools are complemented by systems biology approaches that perturb signaling network components in spatially and temporally controlled ways to illustrate network behavior [1]. The following diagram illustrates a quantitative approach to studying signaling networks:

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols in Quantitative Plant Biology

Advanced Imaging and Phenotyping

Recent advancements employ deep learning-based plant image processing pipelines for species identification, disease detection, cellular signaling analysis, and growth monitoring [3]. These methodologies utilize high-resolution imaging and unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) photography, with image enhancement through cropping and scaling [3]. Feature extraction techniques like color histograms and texture analysis are essential for plant identification and health assessment [3].

Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) represents another powerful quantitative tool, predicting developmental stages by detecting metabolic states that precede visible changes [3]. For example, NIRS of leaf and bud tissue can predict budbreak in apple cultivars the following year, with genome-wide association studies (GWAS) using these predictions identifying quantitative trait loci (QTLs) previously associated with budbreak [3].

Molecular Profiling and Meta-Analysis

Large-scale meta-analyses of molecular datasets identify novel regulatory elements. One study analyzed 105 paired RNA-Seq datasets from Oryza sativa cultivars under salt and drought conditions, identifying 10 genes specifically upregulated in resistant cultivars and 12 genes in susceptible cultivars under both stress conditions [3]. By comparing these with stress-responsive genes in Arabidopsis thaliana, researchers explored conserved stress response mechanisms across plant species [3].

Ensuring Robustness in Complex Experiments

Quantitative approaches emphasize robustness testing to experimental protocol variations, particularly in multi-step plant science experiments [3]. Split-root assays in Arabidopsis thaliana, used to unravel local, systemic, and long-distance signaling in plant responses, show extensive protocol variation potential [3]. Research investigates which variations impact outcomes and provides recommendations for enhancing replicability and robustness through extended protocol details [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Materials in Quantitative Plant Biology

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Biosensors | In vivo visualization and quantification of signaling molecules with cellular/subcellular resolution [1] | Calcium sensors, pH biosensors, hormone reporters; Enable real-time monitoring of signaling dynamics |

| Near-Infrared Spectrometers (NIRS) | Prediction of developmental stages and metabolic states by detecting biochemical composition [3] | Portable field instruments; Spectral analysis of leaf/bud tissue for trait prediction |

| RNA-Seq Libraries | Transcriptome profiling under various stress conditions; Identification of novel stress-responsive genes [3] | 105 paired datasets for meta-analysis; Resistant vs. susceptible cultivar comparisons |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Systems | Tissue-specific and conditional gene manipulation; Functional validation of identified genes [1] | Conditional knockout systems; Tissue-specific promoters for spatial control |

| Deep Learning Image Analysis Tools | Automated species identification, disease detection, and growth monitoring [3] | High-resolution imaging; UAV photography; Feature extraction algorithms |

| Mathematical Modeling Software | Simulation of signaling networks, metabolic pathways, and growth dynamics [1] [2] | Parameter estimation algorithms; Stochastic modeling frameworks; Network analysis tools |

Quantitative Data in Plant Research: From Roots to Ecosystems

Root System Dynamics and Soil Carbon Sequestration

Research on root iterative effects provides a paradigm for understanding root dynamics and their contribution to soil carbon accrual [4]. The heterogeneous nature of root systems is crucial, with fine root systems of most woody plants divided into at least five distinct root orders exhibiting significant variations in morphological, structural, and chemical traits [4].

Table 2: Quantitative Parameters in Root System Dynamics and Carbon Cycling

| Parameter | Measurement Approach | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Root Turnover Rate | Minirhizotron imaging; Sequential soil coring [4] | Determines root longevity and carbon input timing into soils |

| Root Decomposition Rate | Litter bag experiments; Isotopic tracing [4] | Controls nutrient release and formation of soil organic matter |

| Root Production | Ingrowth core methods; Isotope dilution techniques [4] | Measures carbon allocation belowground and soil exploration capacity |

| Root Order Traits | Architectural analysis; Morphological and chemical profiling [4] | Different root orders have distinct structure-function relationships |

| Particulate Organic Carbon (POC) | Soil fractionation; Chemical analysis [4] | Unprotected organic matter fragments in soil, indicator of carbon storage |

Embracing Noise and Robustness in Plant Systems

Stochastic effects pervade plant biology across scales, from molecules buffeted by thermal noise to environmental fluctuations affecting crops in fields [1]. Quantitative approaches recognize that noise presents both challenges and opportunities:

- Cellular noise impacts vital processes including circadian clocks, gene expression, internal signaling, tropisms, patterning, organ shape plasticity, and seed germination [1]

- Stochastic modeling provides frameworks to understand plant-environment interactions, with elegant models coupling mechanical and stochastic influences describing whole-plant development [1]

- Multi-omics technologies enable discovery of genetic features shaping noise levels in transcripts and metabolites [1]

- Bet-hedging strategies in seeds exploit noise, where a generation germinating at different times increases robustness to unpredictable environmental change compared to synchronous germination [1]

Future Perspectives and Applications

Quantitative plant biology opens new research avenues by focusing on questions rather than specific techniques [1]. This interdisciplinary approach fuels creativity and triggers novel investigations by making hypotheses truly testable and interoperable [1]. The field increasingly incorporates citizen science and transdisciplinary projects, questioning and improving human interactions with plants [1].

Future developments will likely expand the use of machine learning approaches to identify complex relationships between inputs and outputs in signaling networks [1], coupled with continued advancement in inferring signaling networks from large genomic datasets [1]. The iterative cycle of measurement, modeling, and validation will remain fundamental as quantitative plant biology continues to transform our understanding of plant systems across scales from molecular interactions to ecosystem dynamics [1].

In plant systems, robust decision-making emerges from the sophisticated management of stochasticity. Quantitative biology reveals that plants employ dynamic mechanisms to suppress, buffer, and even leverage stochastic variation across molecular, cellular, and organ-level scales. This in-depth technical guide examines the core quantitative features—biological noise, developmental robustness, and feedback regulation—that underpin plant adaptation to fluctuating environments. We synthesize current research on the genetic and biophysical principles enabling noise compensation, explore how positive and negative feedback loops generate stable oscillations, and provide structured experimental protocols for quantifying these phenomena. Framed within the broader context of quantitative plant biology, this review serves as a resource for researchers aiming to dissect the complex, self-organizing systems that ensure plant survival and fitness.

Quantitative plant biology uses numbers, mathematics, and computational modeling to move beyond descriptive studies and understand the functional dependencies in biological systems [1]. This approach treats plants as complex, multiscale systems where stochastic influences and regulatory networks interact across spatial and temporal dimensions. A core principle is the iterative cycle of quantitative measurement, statistical analysis, hypothesis testing via modeling, and experimental validation [1].

This review focuses on three interconnected pillars:

- Noise: Defined as stochastic variation, it is a ubiquitous feature affecting everything from gene expression to organ-level growth [5] [1].

- Robustness: The ability of a system to maintain consistent functionality despite internal and external perturbations [6].

- Feedback Loops: Network motifs that either stabilize (negative feedback) or amplify (positive feedback) signals, which are fundamental to generating robust outputs from noisy inputs [7].

Understanding their interplay is crucial for deciphering how sessile plants achieve remarkable developmental precision in inherently unpredictable environments.

The Ubiquity and Nature of Noise in Plant Systems

Noise, or stochastic variation, is an inescapable factor shaping plant life at every scale. Quantitative studies distinguish between external noise from environmental fluctuations and internal noise originating from stochastic biochemical processes within the organism [5].

Table: Classification and Examples of Noise in Plant Systems

| Scale | Noise Type | Quantitative Example | Biological Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular | Transcriptional Noise | Up to 5-fold variation in gene expression within a single E. coli cell [5]. Similar observations in plants [5]. | Affects fidelity of signal transduction and metabolic pathways. |

| Cellular | Growth Rate Heterogeneity | Adjacent cells in Arabidopsis sepals show considerable variability in growth rates [5]. | Contributes to organ shape plasticity and developmental patterns. |

| Organ/Organism | Environmental Fluctuations | Light availability: 100 to 1500 PPFD hourly; Temperature: 4–25°C daily [5]. | Challenges metabolic and developmental processes; requires robust sensing and response. |

| Population | Bet-hedging Strategies | Variation in seed germination timing within a single generation [1]. | Increases fitness and survival in unpredictable environments. |

Beneficial Noise: Beyond Nuisance

Counterintuitively, noise is not always a detriment. Plants can exploit stochasticity for adaptive advantages:

- Stochastic Resonance: Low noise levels can facilitate the detection of sub-threshold input signals, enhancing an organism's responsiveness to faint environmental cues [5].

- Bet-hedging: Population-level strategies, such as non-synchronous seed germination, exploit noise to ensure that at least some offspring survive unpredictable environmental changes [1].

- Developmental Plasticity: Cellular heterogeneity in growth and gene expression can provide a source of variation that allows organs to adapt their final shape robustly [6].

Mechanisms for Ensuring Robustness

Robustness is an emergent property of complex biological systems. Research has identified several key mechanisms by which plants buffer noise to ensure stable developmental outcomes.

Molecular and Genetic Buffering Strategies

- Feedback Loops: Negative feedback is a fundamental engineering principle imported into biology, enabling systems to maintain stability and high fidelity in their outputs despite noisy inputs [5]. For instance, feedback from ERK to RAF in mammalian cells can create stable, adapted, or oscillatory outputs [1].

- Genetic Redundancies: Multigene families and overlapping pathways can provide a buffer against stochastic variation, though these are often evolutionary transitional states [5].

- Post-Transcriptional Buffering: Mechanisms mediated by complexes like Paf1C and microRNAs (miRNAs) can dampen noise in gene expression, providing a layer of regulation that ensures consistent protein levels [6].

Cellular and Tissue-Level Buffering Strategies

- Spatiotemporal Averaging: At the cellular level, noise in the growth rate of individual cells can be buffered by integrating information over space and time. Neighboring cells can compensate for each other's stochastic variations, leading to robust organ-level growth [6].

- Precision in Cell Division: Mechanisms exist to improve the precision of cell division planes and rates, buffering against heterogeneity that could disrupt tissue architecture [6].

- Coordination of Timing: Robust development also relies on the coordination of growth rates and developmental timing between different parts of an organ, ensuring harmonious overall morphology [6].

The Central Role of Feedback Loops

Feedback loops are critical network motifs that directly shape the robustness and dynamics of plant systems, particularly in generating and maintaining oscillations like the circadian clock.

Comparative Analysis of Feedback Loop Motifs

A systematic analysis of circadian oscillators revealed distinct roles for different feedback architectures [7].

Table: Robustness and Temperature Compensation in Circadian Oscillator Models

| Oscillator Model | Core Feedback Structure | Robustness to Parameter Variation (% CV of Period) | Performance in Temperature Compensation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Two-Variable-Goodwin-NFB | Negative Feedback Loop (NFB) | 1.8571% (Least Robust) | Best Performance |

| cyano-KaiABC | Positive Feedback Loop (PFB) | Data Not Explicitly Shown | Data Not Explicitly Shown |

| Combined PN-FB | Positive + Negative Feedback | Most Robust (Narrowest Period Distribution) | Data Not Explicitly Shown |

| Selkov-PFB | Positive Feedback with Substrate Depletion | Data Not Explicitly Shown | Data Not Explicitly Shown |

Key findings from this study include:

- Negative Feedback is superior for temperature compensation, maintaining a steady period despite reaction rates being inherently temperature-sensitive [7].

- Positive Feedback can reduce extrinsic noise (fluctuations in environmental factors or cellular components), while negative feedback is more effective at reducing intrinsic noise (randomness in biochemical reactions) [7].

- Interlinked Positive and Negative Feedback Loops (cPNFB) create oscillatory networks that are highly robust to parameter variations, showing the narrowest distribution of oscillation periods when parameters are perturbed [7].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Quantifying noise, robustness, and feedback requires a combination of high-resolution data acquisition and computational modeling.

Protocol for Robustness Analysis of Oscillatory Networks

This protocol, adapted from [7], details how to assess the robustness of a biological oscillator, such as the circadian clock, to parameter variations.

System Definition and Model Construction

- Define the network topology (e.g., negative feedback, positive feedback, or combined).

- Formulate the mathematical equations (typically ordinary differential equations, ODEs) describing the system's dynamics. Include terms for the temperature dependence of parameters where applicable for temperature compensation studies.

Parameter Sampling for Robustness

- Identify all kinetic parameters in the model (e.g., transcription, translation, and degradation rates).

- Generate a large number (e.g., N=1000) of parameter sets by sampling from a log-normal distribution. This simulates extrinsic fluctuations in the biochemical environment. The multiplicative factor for each parameter should have a mean of 1 and a standard deviation (e.g., 0.0142) reflective of expected biological variation.

Numerical Simulation and Period Calculation

- For each sampled parameter set, numerically integrate the model equations to simulate the system's behavior over time.

- Calculate the period of oscillation for each successful simulation using methods like peak detection or autocorrelation.

Quantitative Robustness Metric Calculation

- Compute the Percentage Coefficient of Variation (% CV) for the resulting distribution of oscillation periods.

- % CV = (Standard Deviation of Periods / Mean Period) × 100%.

- A lower % CV indicates a more robust oscillator, as its period is less sensitive to parameter variations.

Quantifying Cellular Heterogeneity and Growth Compensation

This protocol outlines methods to study noise and robustness in developing tissues, such as the Arabidopsis sepal [5] [6].

Live Imaging and Data Acquisition

- Use confocal or light-sheet microscopy to acquire time-lapse images of a growing plant organ expressing fluorescent markers for cell membranes (e.g., pPIN::PIN1-GFP).

- Maintain plants in a controlled environment chamber during imaging to minimize external noise.

Image Processing and Data Extraction

- Segment individual cells in each frame of the time-lapse series using image analysis software (e.g., MorphoGraphX).

- Track each cell through time to generate a lineage.

- Extract quantitative data for each cell, including:

- Growth Rate: Change in cell area over time.

- Division Timing: Cell cycle duration.

- Gene Expression Levels: Fluorescence intensity of transcriptional reporters.

Statistical Analysis of Heterogeneity

- Calculate descriptive statistics (mean, variance, standard deviation) for growth rates and division timings across the tissue.

- The high cell-to-cell variability in these metrics quantifies the level of intrinsic noise.

Analyzing Buffering Mechanisms

- Perform spatial correlation analysis to determine if the growth of a cell is independent of its neighbors (indicating no compensation) or negatively correlated (indicating active growth compensation).

- Test the role of specific genes by repeating the analysis in relevant mutants (e.g., microtubule organization mutants) and comparing the heterogeneity and correlation patterns to wild-type.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table: Key Reagents and Technologies for Quantitative Plant Research

| Reagent / Technology | Primary Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Biosensors (e.g., for Ca²⁺, ROS, hormones) | In vivo visualization and quantification of signaling molecules with cellular/subcellular resolution [1]. | Elucidating rapid, long-distance electrical and calcium signaling in response to wounding [1]. |

| Advanced Microscopy (Confocal, Light-Sheet) | High spatiotemporal resolution imaging of growth and gene expression in living tissues [8] [6]. | Quantifying cellular heterogeneity in growth rates and division patterns in Arabidopsis sepals [5] [6]. |

| Computational Modeling & Simulation | In silico hypothesis testing and exploration of network dynamics that are difficult to probe experimentally [7] [1]. | Comparing robustness of different feedback loop architectures in circadian clocks [7]. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 for Tissue-Specific Gene Editing | Conditional knockout of target genes in specific cell types or developmental stages [1]. | Uncovering the distinct roles of redundant genes by manipulating them with spatial and temporal control. |

| Transcriptional & Translational Reporters | Quantifying noise in gene expression at the single-cell level [5] [1]. | Measuring cell-to-cell variation in mRNA and protein production in stable transgenic lines. |

The quantitative dissection of noise, robustness, and feedback loops reveals the fundamental design principles of plant systems. Plants are not merely passive victims of stochasticity but have evolved intricate strategies to buffer, suppress, and even harness noise to navigate their unpredictable environments. The interplay of specific network motifs—particularly interlinked positive and negative feedback loops—provides a powerful mechanism for generating robust, temperature-compensated oscillations. As the field of quantitative plant biology advances, driven by more sophisticated biosensors, imaging techniques, and computational models, our ability to predict and manipulate these features will grow. This knowledge is pivotal not only for basic science but also for future applications in crop improvement, where enhancing robustness to environmental stress is a critical goal.

Plant science is undergoing a profound transformation, evolving from a primarily descriptive discipline into a quantitative science powered by engineering principles, physical laws, and sophisticated computational modeling. This paradigm shift enables researchers to move beyond observational studies toward predictive, mechanistic understanding of plant growth, development, and environmental responses. The integration of simulation intelligence—the merger of scientific computing and artificial intelligence—represents a frontier in this transformation, creating new frameworks for understanding plant systems across multiple spatial and temporal scales [9]. This whitepaper examines the core interdisciplinary approaches bridging these traditionally separate fields, providing technical guidance for researchers leveraging quantitative biology to advance plant science research and applications.

Core Computational Modeling Approaches

Simulation Intelligence in Plant Modeling

Simulation intelligence (SI) has emerged as a powerful paradigm for comprehending and controlling complex plant systems through nine interconnected technology motifs [9]. These motifs enable researchers to address fundamental challenges in plant modeling, including inverse problem solving (inferring hidden states or parameters from observations) and uncertainty reasoning (quantifying both epistemic and aleatoric uncertainty) [9].

Table 1: Simulation Intelligence Motifs in Plant Science Applications

| SI Motif | Core Function | Plant Science Application |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-scale and multi-physics modeling | Integrates different types of simulators | Connects molecular, cellular, organ, and plant-level processes [9] |

| Surrogate modeling and emulation | Replaces complex models with faster approximations | Creates digital twins of plant systems for rapid decision support [9] |

| Simulation-based inference | Uses simulators to infer parameters or states | Infers root properties from electrical resistance tomography [9] |

| Causal modeling and inference | Identifies causal relationships within models | Uncovers causal drivers in gene regulatory networks [9] |

| Agent-based modeling | Simulates systems as collections of autonomous agents | Models plant architecture as populations of semi-autonomous modules [10] |

| Probabilistic programming | Interprets code as stochastic programs | Quantifies uncertainty in plant growth predictions [9] |

| Differentiable programming | Computes gradients of computer code/simulators | Enables neural ordinary differential equations for unknown dynamics [9] |

| Open-ended optimization | Finds continuous improvements | Optimizes plant traits for breeding programs [9] |

| Program synthesis | Automatically discovers code to solve problems | Generates L-systems to describe plant development [9] |

Spatial Modeling of Plant Development

Spatial models of plant development represent plant geometry either as a continuum (particularly for individual organs) or as discrete components (modules) arranged in space [10]. These models can be static (capturing form at a particular time) or developmental (describing form as a result of growth), with the latter being either descriptive (integrating measurements over time) or mechanistic (elucidating development through underlying processes) [10].

Figure 1: Classification of spatial modeling approaches in plant development science

Advanced Imaging and Visualization Technologies

Expansion Microscopy for Super-Resolution Imaging

Expansion microscopy techniques have been recently optimized for plant systems, overcoming the challenges presented by rigid cell walls. The ExPOSE (Expansion Microscopy for Plant Protoplasts) protocol enables high-resolution visualization of cellular components through physical expansion of specimens [11].

Table 2: Expansion Microscopy Techniques for Plant Systems

| Technique | Sample Preparation | Expansion Factor | Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ExPOSE | Enzymatic digestion of cell walls to isolate protoplasts, fixation, protein-binding anchor treatment, hydrogel embedding | >10-fold physical expansion | Protein localization, DNA architecture, mRNA foci, biomolecular condensates [11] | Requires protoplast isolation, not for whole tissues |

| PlantEx | Cell wall digestion step optimized for whole plant tissues | Not specified | Subcellular imaging in Arabidopsis root tissue combined with STED microscopy [11] | Fixed tissues only, requires calibration for different species |

The PlantEx methodology includes the following key steps:

- Tissue Fixation: Chemical preservation of tissue structure

- Cell Wall Digestion: Enzymatic treatment to enable hydrogel penetration

- Anchor Treatment: Application of protein-binding anchors to cellular components

- Hydrogel Embedding: Incorporation into swellable polyelectrolyte gel

- Expansion: Immersion in water resulting in physical magnification

- Imaging: High-resolution visualization using standard confocal or STED microscopy [11]

3D Gaussian Splatting for Plant Phenotyping

The PlantGaussian approach represents one of the first applications of 3D Gaussian splatting techniques in plant science, generating realistic three-dimensional visualization for plants across time and scenes [12]. This method integrates the Segment Anything Model (SAM) and tracking algorithms to overcome limitations of classic Gaussian reconstruction in complex planting environments. A mesh partitioning technique converts Gaussian rendering results into measurable plant meshes, enabling accurate 3D plant morphological phenotyping with average relative error of 4% between calculated values and true measurements [12].

Figure 2: PlantGaussian workflow for 3D plant phenotyping from image sequences

Synthetic Biology and Genetic Circuit Engineering

Engineering Genetic Switchboards

Synthetic gene circuits offer a precise approach to engineering plant traits by regulating gene expression through programmable operations. These circuits function through logical operations (AND, OR, NOR gates) and require orthogonality—genetic parts designed to interact strongly with each other while minimizing unintended interactions with other cellular components [11].

The core architecture of synthetic gene circuits includes:

- Sensors: Detect molecular or environmental inputs via inducible promoters

- Integrators: Process signals using engineered promoters, recombinases, or CRISPR repressors

- Actuators: Execute responses by modifying cell function, controlling endogenous genes, or influencing metabolic pathways [11]

Bacterial allosteric transcription factors (aTFs) offer a promising mechanism combining sensing of specific metabolites with regulated gene expression but require further optimization for efficient function in plant systems [11].

Implementation Challenges and Solutions

Major challenges in plant synthetic biology include long development times compared to bacteria, inefficient gene targeting, lack of standardized DNA delivery methods, and whole-plant regeneration constraints [11]. Research teams are addressing these limitations through:

- Transient Expression Systems: Accelerating testing before stable transformation

- Computational Modeling: Predicting circuit behavior before implementation

- High-Throughput Screening: Rapid evaluation of multiple designs

- Targeted Transgene Integration: Improving precision of genetic modifications

Advances in these areas will unlock new plant traits, improve crop resilience, and enhance fundamental plant research [11].

Case Studies: Interdisciplinary Approaches in Action

Brassinosteroid Regulation of Root Growth

A recent interdisciplinary study combined single-cell RNA sequencing, vertical microscopy with automatic root tracking, and computational modeling to elucidate how brassinosteroids regulate root cell proliferation in Arabidopsis thaliana [11].

Experimental Protocol:

- Single-Cell RNA Sequencing: Transcriptomic profiling of individual root cells throughout cell cycle progression

- Live-Cell Imaging: Vertical microscopy with automatic root tracking to monitor brassinosteroid activity via fluorescence

- Computational Modeling: Simulation of growth in root meristem using collected data

Key Findings:

- Brassinosteroid activity increases during G1 phase of cell cycle

- Uneven distribution of brassinosteroid signaling components leads to asymmetric cell division

- Division produces one brassinosteroid-active cell and one supporting cell

- This asymmetric division avoids negative feedback between signaling and biosynthesis, allowing increased cell proliferation [11]

Mechanical Regulation of Hypocotyl Elongation

Research on Arabidopsis hypocotyl elongation demonstrates how mechanical techniques combined with molecular biology reveal fundamental growth mechanisms. The study integrated time-lapse photography, chemical quantification, immunohistochemical analysis, Raman microscopy, and atomic force microscopy [11].

Methodological Workflow:

- Time-Lapse Photography: Quantified hypocotyl elongation kinetics during dark-to-light transition

- Immunohistochemistry: Localized pectin accumulation in cell walls

- Raman Microscopy: Identified polarized pectin distribution to transverse walls

- Atomic Force Microscopy: Measured elastic modulus of cell walls

- Genetic Analysis: Used hy5 mutants to establish molecular pathway

Mechanistic Insight: Light-stabilized HY5 suppresses miR775, allowing upregulation of GALACTOTRANSFERASE9 (GALT9), which polarizes pectin to transverse cell walls, increasing their elastic modulus and inhibiting hypocotyl elongation [11].

Figure 3: Molecular mechanical pathway regulating hypocotyl elongation in response to light

Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Plant Systems Biology

| Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Imaging Technologies | ExPOSE protocol | Expansion microscopy for plant protoplasts [11] |

| PlantEx protocol | Expansion microscopy for whole plant tissues [11] | |

| PlantGaussian | 3D Gaussian splatting for plant phenotyping [12] | |

| Genetic Tools | Synthetic gene circuits | Programmable regulation of gene expression [11] |

| Bacterial allosteric transcription factors (aTFs) | Combining metabolite sensing with gene regulation [11] | |

| CRISPR repressors | Signal integration in synthetic circuits [11] | |

| Computational Frameworks | Simulation Intelligence motifs | Nine technology paradigms for plant modeling [9] |

| L-systems | Mathematical basis for architectural plant modeling [10] | |

| Neural ordinary differential equations | Combining solvers with machine learning [9] | |

| Analytical Techniques | Single-cell RNA sequencing | Transcriptomic profiling of individual plant cells [11] |

| Atomic Force Microscopy | Measuring mechanical properties of cell walls [11] | |

| Raman microscopy | Chemical imaging of cell wall components [11] |

Future Perspectives and Applications

The integration of engineering principles, physics-based modeling, and computational approaches is positioned to revolutionize plant science research and application. Key future directions include:

Accelerated Design-Build-Test-Learn Cycles: Developing faster iteration protocols to overcome the long development times currently limiting plant synthetic biology [11]

Multi-Scale Model Integration: Creating frameworks that seamlessly connect molecular, cellular, organ, and whole-plant levels of organization [9]

Digital Twin Technology: Expanding the use of surrogate models that accurately mimic plant systems for rapid prediction and optimization [9]

Cross-Kingdom Translation: Leveraging plant systems to identify orthologs linked to human diseases and biological processes relevant to medical treatments [11]

These approaches will be essential for addressing global challenges in food security, climate resilience, and sustainable agriculture through improved crop varieties and management strategies. As quantitative biology approaches mature, they will enable unprecedented predictive capability in plant science, from molecular mechanisms to ecosystem-level interactions.

In the evolving landscape of quantitative biology, plant science research increasingly relies on computational modeling to decipher complex biological systems. Two fundamentally distinct approaches—pattern models and mechanistic mathematical models—serve complementary roles in biological inquiry. Pattern models, including statistical and machine learning approaches, excel at identifying correlations and spatial-temporal relationships within large datasets. In contrast, mechanistic mathematical models formalize hypotheses about underlying biological processes, enabling researchers to test causality and generate testable predictions. This technical guide examines the theoretical foundations, practical applications, and methodological integration of these modeling paradigms within plant biology, providing researchers with a framework for selecting and implementing appropriate computational approaches based on specific research objectives.

The increasing availability of high-throughput biological data presents both opportunities and challenges for integration and contextualization. As noted by Poincaré, "A collection of facts is no more a science than a heap of stones is a house" [13]. Mathematical modeling provides a framework for describing complex systems in a logically consistent, explicit manner, allowing researchers to relate possible mechanisms and relationships to observable phenomena [13]. In plant biology, where systems exhibit remarkable complexity across multiple spatial and temporal scales, computational approaches have become indispensable tools for advancing our understanding of developmental processes, environmental responses, and evolutionary adaptations.

Plant systems present unique challenges and opportunities for computational modeling. Unlike animal cells, plant cells are immobile and establish position-dependent cell lineages that rely heavily on external cues [14]. This spatial constraint means that intercellular communication is vital for establishing and maintaining cell identity, making positional information a critical factor in developmental models [14]. Furthermore, plants maintain pools of stem cells throughout their life spans, driving continuous growth and adaptation—a feature that requires models capable of capturing dynamic processes across extended timeframes [14].

Conceptual Foundations: Pattern Models vs. Mechanistic Mathematical Models

Defining Pattern Models

Pattern models test hypotheses about spatial, temporal, or relational patterns between system components such as individual plants, proteins, or genes [13]. These models are typically "data-driven," involving the identification of patterns from datasets using methods from bioinformatics, statistics, and machine learning [13]. The mathematical representation in pattern models is based on assumptions about the data and statistical properties, such as regulatory network topology or appropriate probability distributions for phenotypic data [13].

In plant biology, pattern models are widely applied to analyze genomics, phenomics, proteomics, and metabolomics data. For example, RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data is frequently analyzed using software such as DESeq2, which employs generalized linearized modeling approaches with negative binomial distributions to identify genes whose expression changes under treatment conditions [13]. Similarly, transcriptome-wide association studies (TWAS) utilize pattern models to identify correlations between transcript abundance and phenotypic traits [13].

Defining Mechanistic Mathematical Models

Mechanistic mathematical models describe the underlying chemical, biophysical, and mathematical properties within a biological system to predict and understand its behavior mechanistically [13]. These models balance biological realism with parsimony, focusing on the simplest but necessary core processes and components—a knowledge-generating process in itself [13]. Unlike pattern models, mechanistic models permit the rigorous study of hypotheses about phenomena without extensive data collection, enabling researchers to eliminate possibilities based on current understanding before experiments are conducted [13].

Common mechanistic modeling approaches in plant biology include ordinary differential equations (ODEs) that specify how components change with respect to time or space, such as biochemical reactions altering protein concentrations [13]. These models contain parameters representing the strength and directionality of interactions, which may be estimated from existing data or literature [13]. Well-known mechanistic relationships in biology include density-dependent degradation producing exponential decay, the law of mass-action in biochemical kinetics, and logistic population growth [13].

Comparative Framework

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between Pattern and Mechanistic Models

| Characteristic | Pattern Models | Mechanistic Mathematical Models |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Identify correlations and patterns in data | Understand underlying processes and causality |

| Approach | Data-driven | Hypothesis-driven |

| Complexity | May use thousands of parameters (e.g., neural networks) | Emphasizes parsimony and simplicity |

| Interpretation | Correlation does not imply causation | Designed to establish causal relationships |

| Data Requirements | Large datasets for training and validation | Can operate with limited data through parameter estimation |

| Common Applications | Genome annotations, phenomics, transcriptomics | Biochemical kinetics, biophysics, population dynamics |

Modeling Approaches in Plant Biology Research

Gene Expression Analysis

In plant gene expression studies, both pattern and mechanistic models contribute distinct insights. Pattern models dominate transcriptomics research, where tools like DESeq2 identify differentially expressed genes using statistical frameworks [13]. Weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) and circadian-aware statistical models like JTK_Cycle identify functionally correlated transcripts across experimental conditions [13]. These approaches excel at detecting linear relationships between gene expression variation and putative drivers such as different genotypes.

However, the underlying processes driving plant adaptation and behavior are fundamentally nonlinear, limiting the discovery potential of correlation-based approaches [13]. Mechanistic mathematical models address this limitation by representing the processes potentially driving observed expression patterns. For example, mechanistic models have demonstrated how developmental timing stochasticity explains "noise" and patterns of gene expression in Arabidopsis roots [13]. These models can incorporate known biological constraints and generate testable predictions about regulatory relationships.

Plant Stem Cell Regulation and Development

The regulation of plant stem cells presents a compelling application for both modeling approaches. Pattern models can identify transcriptional signatures associated with stem cell populations, while mechanistic models can formalize hypotheses about the regulatory networks maintaining stem cell niches.

In the root apical meristem (RAM), mechanistic models have elucidated how hormonal gradients position the stem cell niche and regulate the transition from cell division to differentiation [14]. complementary patterns of auxin and cytokinin signaling define spatial boundaries, with auxin regulating stem cell divisions and cytokinin triggering the transition to differentiation [14]. Similar regulatory logic operates in reverse in the shoot apical meristem (SAM), where cytokinins promote cell proliferation in the central zone while local auxin accumulation drives organogenesis in the peripheral zone [14].

Table 2: Experimental Approaches in Plant Stem Cell Research

| Experimental Approach | Methodology | Key Insights |

|---|---|---|

| Stem cell ablation studies | Laser-mediated elimination of specific cells followed by observation of regenerative responses | Demonstrated that most cell types in the meristem can adopt new position-dependent fates [14] |

| Hormonal signaling manipulation | Genetic or pharmacological alteration of auxin/cytokinin biosynthesis, transport, or response | Revealed antagonistic interaction between auxin and cytokinin in establishing division-differentiation boundaries [14] |

| Transcriptional reporter analysis | Live imaging of fluorescent reporters for hormone signaling or cell identity markers | Identified gradients of hormone response that correlate with cell fate decisions [14] |

| Computational modeling | Integration of experimental data into mathematical frameworks representing regulatory networks | Predicted emergent properties of stem cell regulatory networks and identified critical feedback loops [14] |

Root Development and Patterning

Plant root development exemplifies the successful integration of modeling approaches with experimental biology. Root systems exhibit clearly defined developmental zones along their longitudinal axis, providing a natural model for studying transitions from cell division to differentiation [14]. The root's primary axis serves as a linear timeline of development from stem cell to differentiated tissue, making it particularly amenable to computational modeling [15].

Mechanistic models have been instrumental in understanding how positional information guides root development. Classical concepts like Wolpert's French flag model of positional information and Turing's reaction-diffusion systems have found application in explaining root patterning phenomena [15]. For example, mechanistic models have demonstrated how an auxin minimum at the boundary between the meristematic and elongation zones provides a positional cue for the switch to differentiation [14]. These models integrate known interactions between hormonal signaling components, transcription factors, and cellular growth processes to explain emergent patterning.

Methodological Implementation

Building Effective Mechanistic Models

Constructing useful mechanistic models requires careful consideration of purpose and appropriate simplification. Unlike descriptive models that aim to represent reality in detail or predictive models like weather forecasts that prioritize quantitative accuracy, mechanistic models in developmental biology serve to illuminate underlying mechanisms [15]. Good mechanistic models incorporate sufficient detail to capture essential processes while remaining simple enough to facilitate understanding and analysis.

The process of determining which elements to include in a model requires deep knowledge of the biological system. Modelers must identify key genes, hormones, interactions, cellular behaviors, and mechanical processes relevant to the developmental phenomenon being studied [15]. For instance, modelers often collapse transcription and translation into a single equation when mRNA and protein expression domains are similar, but maintain separate equations when their dynamics significantly differ [15]. Similarly, linear pathways without feedback can be simplified, while pathways with regulatory loops require more complete representation.

Experimental Validation Frameworks

Robust validation is essential for both pattern and mechanistic models. For mechanistic models, sensitivity analyses demonstrate that qualitative behavior persists across moderate parameter variations, indicating generic rather than fine-tuned behavior [15]. Additionally, effective models should generate distinguishable predictions for different biological hypotheses, enabling experimental discrimination between competing explanations.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Plant Systems Biology

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Reporters | DII-VENUS (auxin sensor), DR5rev:GFP (auxin response), TCSn:GFP (cytokinin response) | Live imaging of hormone signaling gradients and responses in developing tissues [14] |

| Genetic Tools | Tissue-specific inducible cre/lox systems, CRISPR-Cas9 for genome editing, RNAi lines | Precise manipulation of gene expression in specific cell types or developmental stages [14] |

| Bioinformatics Software | DESeq2, WGCNA, Seurat, Monocle | Statistical analysis of transcriptomic data, identification of co-expression networks, single-cell analysis [13] |

| Modeling Platforms | Virtual Plant, VCell, Morpheus, COPASI | Simulation environments for constructing and analyzing computational models of plant development [15] |

| Imaging and Analysis | Confocal microscopy, light sheet microscopy, MorphoGraphX | High-resolution imaging and quantitative analysis of plant morphology and gene expression patterns [13] |

Integration and Future Perspectives

The most powerful applications of computational modeling in plant biology emerge from the strategic integration of pattern and mechanistic approaches. Pattern models can identify correlations and generate hypotheses from large datasets, while mechanistic models can formalize these hypotheses into testable frameworks. Iterative cycling between these approaches—where mechanistic model predictions inform new experimental designs whose results refine pattern detection—accelerates biological discovery.

Future advances in plant systems biology will likely involve multi-scale models that integrate processes from molecular interactions to tissue-level patterning. Such models will need to incorporate mechanical forces, hormonal gradients, gene regulatory networks, and environmental responses into unified frameworks. Additionally, machine learning approaches may enhance mechanistic modeling by helping to parameterize models from complex data or by identifying previously unrecognized patterns that suggest new mechanistic hypotheses.

For researchers adopting computational approaches, successful integration requires collaborative, interdisciplinary teams that include both experimental biologists and quantitative modelers. Starting with well-defined biological questions, clearly articulating modeling objectives, and maintaining open communication between team members are critical factors for productive collaboration. Through such integrated approaches, plant biology will continue to unravel the complex mechanisms underlying plant development, adaptation, and evolution.

Quantitative Toolkits: AI, Proteomics, and Modeling for Plant System Analysis and Biotech Innovation

The field of plant science is undergoing a profound transformation, evolving into a rigorously quantitative discipline driven by artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML). This paradigm shift addresses the urgent need to solve modern agricultural challenges, including rising global population pressures, climate change, and the necessity to reduce environmental harm from farming practices [16]. Traditional methods like marker-assisted selection, manual phenotyping, and linear regression models increasingly struggle to meet these demands, particularly in addressing complex, nonlinear relationships inherent in plant biological systems [16]. AI and ML technologies provide powerful new methodologies to decipher these complexities, enabling researchers to move beyond phenomenological descriptions toward predictive, mechanism-based understanding of plant growth, development, and responses to environmental stresses. This transition is foundational to advancing food security, enhancing agricultural sustainability, and unlocking new frontiers in plant biology through quantitative frameworks.

AI Fundamentals for Plant Science

For researchers embarking on AI-driven plant science, a clear understanding of key computational concepts is essential. Artificial Intelligence encompasses systems designed to perform tasks typically requiring human intelligence, such as learning, reasoning, and problem-solving [16]. Machine Learning, a subset of AI, enables computers to identify patterns in data and make predictions without being explicitly programmed for each specific task [16]. Within ML, several specialized approaches have particular relevance for plant science applications:

- Deep Learning: An advanced branch of ML utilizing layered neural network architectures. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are particularly valuable for image analysis, while Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) excel at processing sequential data [16].

- Explainable AI: Focuses on enhancing the transparency and interpretability of AI systems, which is critical in biological applications where understanding decision processes is scientifically essential [16].

- Federated Learning: Supports collaborative model training across distributed data sources while maintaining data privacy and security—an important consideration for multi-institutional research projects [16].

- Generative Models: Including Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), these can generate synthetic data that closely resembles real-world observations, offering valuable tools for data augmentation and simulation when real data is limited [16].

These foundational methodologies enable the analysis of complex, high-dimensional datasets generated by modern plant phenotyping platforms, genomic sequencing technologies, and environmental sensor arrays, forming the computational backbone of contemporary quantitative plant biology.

AI in Precision Breeding

Genomic Selection and Trait Prediction

AI-powered genomic selection represents one of the most transformative applications of machine learning in plant breeding. By integrating ML algorithms with massive genomic datasets, breeders can now associate genetic markers with desirable traits and predict breeding values of potential parent lines without extensively phenotyping every plant generation [17]. These models process multidimensional genomic and phenotypic information to estimate the likelihood that a particular genotype will express target traits in the field, even under unpredictable environmental conditions [17]. This approach has demonstrated significant practical impact, achieving up to 20% yield increase in trials and drastically reducing breeding cycles by 18-36 months compared to conventional methods [17].

Precision Cross-Breeding Optimization

AI tools have revolutionized cross-breeding strategies through predictive models that simulate vast combinations of parent lines to anticipate which crosses will yield optimal trait combinations for yield, resilience, and nutritional value [17]. These AI-based systems analyze multidimensional trait datasets—including biomass growth, root architecture, and nutrient uptake—to select optimal parental pairs, simulating thousands of potential outcomes to focus breeders' resources on the most promising crosses [17]. The result is a more efficient breeding pipeline that delivers diverse, elite crop varieties tailored for specific regions and climates, with estimated time savings of 18-24 months in variety development cycles [17].

Framework for AI-Enabled Prediction in Crop Improvement

A emerging theoretical framework for AI-enabled prediction in crop improvement brings together elements of dynamical systems modeling, ensembles, Bayesian statistics, and optimization [18]. This framework demonstrates that predicting system process rates represents a superior strategy to predicting system states for complex biological systems, with significant implications for breeding programs [18]. Research has shown that heritability and level of predictability decrease with increasing system complexity, and that ensembles of models can implement the diversity prediction theorem, enabling breeders to identify subnetworks of genetic and physiological networks underpinning crop response to management and environment [18].

Table 1: AI Advancements in Precision Breeding for 2025

| AI Advancement | Main Application | Potential Yield Increase (%) | Estimated Time Savings (months) | Technical Readiness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI-Powered Genomic Selection | Faster, more effective gene stacking | Up to 20% | 18-36 | Mainstream Adoption |

| Precision Cross-Breeding with AI | Diversified, climate-ready varieties | 12-24% | 18-24 | Rapid Growth |

| AI-Driven Climate Resilience Modeling | Crops for unpredictable weather | 10-18% | 12-24 | Piloting/Scaling |

Experimental Protocol: AI-Guided Genomic Selection

Objective: To implement an AI-powered genomic selection pipeline for complex trait improvement.

Materials and Methods:

- Plant Material: A diverse population of 500+ genotypes of the target crop species.

- Genotyping: Extract DNA and perform whole-genome sequencing or high-density SNP chip analysis.

- Phenotyping: Collect high-throughput phenotypic data for target traits across multiple environments and replications.

- Data Preprocessing: Impute missing genomic data and perform quality control on phenotypic measurements.

- Model Training: Partition data into training (80%) and validation (20%) sets. Train multiple ML models (Random Forest, Support Vector Machines, Neural Networks) using genomic markers as features and phenotypic values as targets.

- Model Validation: Evaluate model performance using cross-validation and independent validation sets.

- Genomic Prediction: Apply trained models to predict breeding values for selection candidates based solely on their genomic profiles.

Key Considerations: Ensure balanced representation of environmental conditions in training data. Implement appropriate regularization techniques to prevent overfitting in high-dimensional genomic data [16] [18].

Predictive Phenotyping through AI

High-Throughput Phenomics Platforms

Phenotyping has traditionally represented the primary bottleneck in plant breeding programs, but AI-powered high-throughput phenomics platforms equipped with robotics, drones, and sensors are transforming this critical domain [17]. These systems automatically capture, analyze, and report data on critical traits including leaf size, greenness, shape, biomass growth, root architecture, and stress response indicators [17]. Imaging and sensor data are processed instantaneously by AI algorithms that identify subtle or early-stage differences typically escaping human observers, significantly accelerating selection processes and improving breeding accuracy [17]. These platforms can scale data collection from hundreds to tens of thousands of plants daily, providing real-time feedback to breeders while reducing subjectivity in trait evaluation [17].

Deep Learning for Plant Image Analysis

Recent advancements in deep learning have particularly transformed plant image analysis, with specialized pipelines now available for species identification, disease detection, cellular signaling analysis, and growth monitoring [19]. These computational tools leverage data acquisition methods ranging from high-resolution microscopy to unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) photography, coupled with image enhancement techniques such as cropping and scaling [19]. Feature extraction methods including color histograms and texture analysis have become essential for plant identification and health assessment [19]. The implementation of self-supervised learning techniques with transfer learning has laid the foundation for successful use of domain-specific models in plant phenotyping applications [20].

Stress Detection and Quantification

AI-driven phenotyping platforms excel at detecting and quantifying plant stress responses from both biotic and abiotic factors [20]. For biotic stresses, AI models can identify diseases, insect pests, and weeds through computer vision analysis of imagery from satellites, drones, or ground-based platforms [20]. For abiotic stresses, these systems detect symptoms of nutrient deficiency, herbicide injury, freezing, flooding, drought, salinity, and extreme temperature impacts [20]. This capability enables not only rapid response to stress conditions but also the identification of resistant genotypes for breeding programs, contributing to the development of more resilient crop varieties.

Table 2: AI Applications in Predictive Phenotyping

| Application Area | Primary AI Technology | Data Sources | Key Measurable Traits |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Phenomics | Computer Vision, Deep Learning | UAV, robotic ground platforms, stationary imaging systems | Biomass, architecture, color, growth rates |

| Disease & Pest Detection | Convolutional Neural Networks | Field cameras, drones, handheld devices | Lesion patterns, insect damage, discoloration |

| Abiotic Stress Response | Multispectral Analysis | Thermal, NIR, hyperspectral sensors | Canopy temperature, chlorophyll content, water status |

| Yield Prediction | Ensemble ML Methods | Historical yield data, environmental sensors, satellite imagery | Yield components, fruit count, size estimation |

Experimental Protocol: Deep Learning-Based Plant Disease Detection

Objective: To develop a CNN model for automated detection and classification of plant diseases from leaf images.

Materials and Methods:

- Image Acquisition: Collect a minimum of 5,000 leaf images using standardized imaging protocols across multiple growth stages and lighting conditions.

- Data Annotation: Work with plant pathologists to label images according to disease presence, type, and severity.

- Data Preprocessing: Resize images to uniform dimensions, apply data augmentation techniques (rotation, flipping, brightness adjustment) to increase dataset diversity.

- Model Architecture: Implement a CNN architecture (e.g., ResNet, EfficientNet) with transfer learning from pre-trained weights.

- Model Training: Train the model using categorical cross-entropy loss and adaptive optimization algorithms.

- Validation: Evaluate model performance on held-out test sets using accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score metrics.

- Deployment: Integrate the trained model into a user-friendly application for real-time disease detection.

Key Considerations: Address class imbalance in disease categories through appropriate sampling strategies or loss functions. Ensure model interpretability through gradient-weighted class activation mapping (Grad-CAM) to highlight features influencing predictions [19] [21].

Integrated Workflows and Decision Support Systems

From Vision to Reality: Case Study of Pest-ID

The translational potential of AI in plant science is exemplified by Pest-ID, a tool developed by researchers at Iowa State University that has evolved from a conceptual framework to a practical application used by farmers and growers [21]. This web-based tool allows users to upload photos to identify insects and weeds with over 96% accuracy, providing real-time classification and management recommendations [21]. The system is built on foundation models—"super-massive models that can be fine-tuned for different tasks"—which typically are developed by large AI companies but in this case were created by university researchers [21]. The tool demonstrates the effectiveness of global-to-local datasets that are constantly updated to address emerging pests, showcasing a robust, context-aware, decision-support system capable of early detection and accurate identification followed by expert-validated, region-specific integrated pest management recommendations [21].

Cyber-Agricultural Systems and Digital Twins

The evolution of AI applications in plant science is progressing toward comprehensive cyber-agricultural systems that include digital twins of crops to inform decisions and enhance breeding and sustainable production [21]. In these systems, the physical space serves as the source of information, while the cyberspace uses this generated information to make decisions that are then implemented back into the physical environment [21]. This approach has enormous potential to enhance productivity, profitability, and resiliency while lowering the environmental footprint of agricultural production [21]. The implementation of such systems requires interdisciplinary collaboration across mechanical engineering, computer science, electrical engineering, agronomy, and agricultural and biological engineering [21].

Experimental Protocol: Developing an AI-Based Decision Support System

Objective: To create an integrated AI advisory system for precision farm management.

Materials and Methods:

- Data Collection: Integrate heterogeneous data sources including historical yield maps, real-time sensor data, satellite imagery, weather forecasts, and soil test results.

- Data Fusion: Develop algorithms to spatially and temporally align diverse data streams into a unified data structure.

- Model Integration: Incorporate multiple AI models for specific tasks (disease prediction, yield forecasting, nutrient recommendation).

- Recommendation Engine: Implement a knowledge-based system that translates model predictions into actionable management advice.

- User Interface: Develop an intuitive interface accessible via web and mobile platforms.

- Validation: Conduct field trials to evaluate the impact of AI-generated recommendations on crop performance and resource use efficiency.

Key Considerations: Ensure the system accounts for regional variations in growing conditions and management practices. Incorporate feedback mechanisms to continuously improve recommendation accuracy [17] [21].

The Plant Scientist's AI Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for AI-Driven Plant Science

| Tool/Technology | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Phenotyping Platforms | Automated image acquisition and analysis | Growth monitoring, trait quantification, stress response |

| UAVs (Drones) with Multispectral Sensors | Aerial imagery collection at multiple wavelengths | Field-scale phenotyping, stress mapping, yield prediction |

| Genotyping-by-Sequencing Platforms | High-density genetic marker identification | Genomic selection, genome-wide association studies |

| IoT Sensor Networks | Continuous monitoring of environmental conditions | Microclimate characterization, irrigation scheduling |

- Blockchain Integration: Blockchain technology combined with AI ensures traceability, data integrity, and transparency in breeding pipelines through immutable records of trait selection, parental crosses, and environmental test data [17]. This integration helps prevent seed fraud, preserves genetic purity, and builds stakeholder trust in climate-smart and sustainable crops [17].

- Explainable AI Methods: Techniques such as SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) and LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) help interpret complex AI model decisions, making black-box models more transparent and biologically interpretable [16]. This is particularly important for understanding gene-trait relationships and building scientific knowledge beyond mere prediction.

- Federated Learning Frameworks: These enable collaborative model training across multiple institutions without sharing raw data, addressing privacy concerns while leveraging diverse datasets [16]. This approach is especially valuable for plant science applications where data may be geographically distributed or subject to institutional policies.

Visualizing AI-Driven Plant Research Workflows

AI-Powered Phenotyping-to-Breeding Pipeline

Integrated Cyber-Agricultural System Architecture

Challenges and Future Perspectives

Despite the significant progress in AI applications for plant science, several challenges remain that require interdisciplinary solutions. Data quality and availability represent fundamental limitations, as AI models require large, accurately annotated datasets that may be scarce for certain crops or traits [16]. The integration of data from different domains—genomics, phenomics, environmental monitoring—presents technical challenges due to varying formats and standards [16]. Model interpretability continues to be a significant hurdle, as deep learning models often function as "black boxes" with limited transparency into their decision processes [16]. Biological complexity, particularly the nonlinear relationships between genotype and phenotype influenced by environmental factors, creates challenges for model generalization across different growing conditions [16]. Additionally, infrastructure constraints and ethical considerations regarding data privacy and equitable access to AI technologies must be addressed to ensure broad benefits from these advancements [16].

Future developments in AI-driven plant science will likely focus on integrating mechanistic models with machine learning approaches, combining their data-driven and knowledge-driven strengths to better understand the mechanisms underlying tissue organization, growth, and development [22]. Emerging technologies including quantum computing for analyzing plant genomic data and generative models for simulating plant traits represent promising frontiers [16]. There is also growing interest in applications that span multiple biological scales, from molecular dynamics to ecosystem-level processes, and in approaches that integrate different time scales from milliseconds to generations [22]. As these technologies mature, the plant science community must continue to develop standards, share best practices, and foster collaborations that accelerate progress toward more sustainable and productive agricultural systems.

Table 4: Challenges and Future Directions for AI in Plant Science

| Challenge Area | Current Limitations | Emerging Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Data Quality & Availability | Limited annotated datasets for minor crops | Generative AI for data augmentation, federated learning |

| Model Interpretability | Black-box nature of deep learning models | Explainable AI methods, hybrid mechanistic-ML models |

| Biological Complexity | Nonlinear genotype-phenotype relationships | Multi-scale modeling, knowledge graph integration |

| Scalability & Generalization | Poor performance across environments | Transfer learning, domain adaptation techniques |

| Ethical Implementation | Data privacy, equitable access | Privacy-preserving AI, open-source tools for resource-limited settings |

The field of plant science is undergoing a quantitative revolution, moving beyond descriptive observations to a rigorous, numbers-driven discipline that leverages mathematical models and statistical analyses to form testable hypotheses [1]. This quantitative plant biology approach is essential for understanding complex biological systems across multiple spatial and temporal scales [1]. Within this framework, mass spectrometry (MS)-based proteomics has emerged as a cornerstone technology, providing critical data on protein abundance, modifications, and interactions that drive plant growth, development, and environmental responses [23] [24].

Historically, plant proteomics has lagged behind human health research in adopting cutting-edge technologies due to smaller research communities and less financial investment [23]. However, the past decade has seen remarkable acceleration, with advanced MS platforms and computational tools now being harnessed to unravel the intricate molecular mechanisms that underpin plant biology [23] [24]. This technical guide examines the current state of MS-based proteomics, with particular emphasis on Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) strategies, and provides a practical roadmap for their implementation in plant research to generate robust, quantitative data.

Technological Advances in MS-Based Plant Proteomics

The Shift to Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA)

Traditional Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA) methods, which select the most abundant peptides for fragmentation, are increasingly being supplanted by DIA due to its superior quantitative consistency and depth of proteome coverage [23]. Unlike DDA, DIA fragments all ions within predefined isolation windows across the entire mass range, resulting in more comprehensive and reproducible data acquisition [23].

Recent methodological refinements have further enhanced DIA performance for plant applications. The integration of high-field asymmetric waveform ion mobility spectrometry (FAIMSpro) with BoxCar DIA enables a optimal balance of throughput and data coverage [23] [24]. This combination, particularly in a short-gradient, multi-compensation voltage (Multi-CV) format, significantly improves proteome coverage while maintaining high throughput—a crucial consideration for large-scale experiments analyzing multiple treatment conditions and time points [24]. These workflows now enable the quantification of nearly 10,000 protein groups in studies of plant stress responses, providing unprecedented systems-level views of proteome dynamics [24].

Table 1: Key DIA Methodologies and Their Applications in Plant Proteomics

| Methodology | Key Features | Application in Plant Research |

|---|---|---|

| Standard DIA | Fragments all ions in predefined mass windows; improved quantitative consistency [23] | General comparative proteomics; time-course experiments [24] |

| FAIMSpro + BoxCar DIA | Combines ion mobility separation with wide ion accumulation windows; improves dynamic range and coverage [23] [24] | High-throughput profiling of complex samples; deep proteome mapping [24] |

| Multi-CV FAIMSpro BoxCar DIA | Uses multiple compensation voltages; optimizes balance between throughput and coverage [24] | Detailed temporal response kinetics (e.g., salt/osmotic stress) [24] |

Advanced Workflows for Post-Translational Modification (PTM) Analysis

Protein function is extensively regulated by PTMs, and specialized enrichment strategies are required for their comprehensive analysis. For plant signaling studies, simultaneous monitoring of multiple PTMs provides a more integrated view of regulatory networks. The TIMAHAC (Tandem Immobilized Metal Ion Affinity Chromatography and Hydrophilic Interaction Chromatography) strategy allows for concurrent analysis of phosphoproteomes and N-glycoproteomes from the same sample, revealing potential crosstalk between these modifications during stress responses [24]. Similar advances have improved the coverage of O-GlcNAcylated proteomes through wheat germ lectin-weak affinity chromatography combined with high-pH reverse-phase fractionation [24].

Protein-Protein Interaction Mapping Techniques

Understanding signal transduction requires comprehensive mapping of protein-protein interactions (PPIs). While immunoprecipitation-mass spectrometry (IP-MS) remains valuable, newer techniques offer complementary insights: