Integrating Systems Biology Models in Plant Development: From Foundational Maps to Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on how computational systems biology models are revolutionizing the study of plant development and creating new pipelines...

Integrating Systems Biology Models in Plant Development: From Foundational Maps to Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on how computational systems biology models are revolutionizing the study of plant development and creating new pipelines for drug discovery. We explore foundational genomic atlases, methodological approaches from gene networks to functional-structural plant models, and strategies to overcome key challenges in model adoption and optimization. The content further covers the critical validation of these models through their application in identifying and engineering biosynthetic pathways for plant-derived therapeutics, synthesizing a roadmap for their expanding role in biomedical research.

Mapping the Blueprint: Foundational Genomic Atlases and Core Concepts in Plant Systems Biology

The shift from reductionist approaches to systems biology has revolutionized plant science, and Arabidopsis thaliana has emerged as a cornerstone model organism for this paradigm. Systems biology investigates complex biological systems by examining all components and their relationships within the context of the whole system, recognizing that emergent properties can only be observed through study of the system as a whole rather than its isolated parts [1] [2]. Arabidopsis provides an ideal platform for such investigations due to its simple body plan composed of reiterated elements, continuous postembryonic organ development, and remarkable developmental plasticity [1]. The application of high-throughput technologies to Arabidopsis research has enabled scientists to move beyond studying individual genes or proteins to understanding how these components are coordinated across multiple levels of biological organization—from molecules to cells, tissues, organs, and entire organisms [1].

The fundamental equation of quantitative biology, P = G × E (phenotype equals genotype interacting with environment), encapsulates why Arabidopsis has become so pivotal in systems biology [3]. Its well-characterized genome, combined with the ability to precisely control environmental conditions, makes it possible to deconstruct the complex interactions that give rise to observable traits. As a multicellular eukaryote, Arabidopsis enables the study of developmental processes that require orchestration across multiple cell types, providing insights that extend beyond what can be learned from unicellular model organisms [1]. The lessons learned from Arabidopsis are proving vital for addressing global challenges such as food security and climate resilience in crop species.

Key Biological and Experimental Advantages

Arabidopsis offers a unique combination of biological and experimental characteristics that make it exceptionally suited for systems biology research. Its compact genome of approximately 135 megabase pairs across five chromosomes was the first plant genome to be fully sequenced in 2000, providing an invaluable reference for plant genomics [4] [5]. The genome contains roughly 27,000 genes with relatively low redundancy compared to other plants, simplifying genetic analysis [4]. As a diploid organism with minimal repetitive DNA, Arabidopsis avoids the complications of polyploidy that characterize many crop species [5].

The plant's rapid life cycle of approximately 6-8 weeks from seed germination to seed production enables researchers to study multiple generations within a single research cycle [4] [5]. Each plant can produce thousands of seeds, facilitating extensive genetic experiments and statistical analyses [4]. Its small size allows cultivation of numerous individuals in controlled environments, with up to 484 plants monitored simultaneously in high-throughput phenotyping systems [3]. The ability to grow Arabidopsis under sterile conditions on Petri plates provides exceptional control over experimental variables, while its self-compatibility simplifies genetic crosses and maintenance of homozygous lines [5].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Arabidopsis thaliana as a Model Organism

| Characteristic | Specification | Research Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Genome Size | ~135 megabase pairs [4] | Easier sequencing, manipulation, and analysis |

| Ploidy | Diploid (2n=10) [4] | Simpler genetic analysis compared to polyploid plants |

| Life Cycle | 6-8 weeks [4] | Multiple generations can be studied in a single research cycle |

| Seed Production | Thousands per plant [4] | Enables extensive genetic and statistical analyses |

| Physical Size | 20-25 cm height [4] | High-density cultivation in controlled environments |

| Transformation | Agrobacterium-mediated floral dip [5] | Efficient genetic modification without tissue culture |

Beyond these practical advantages, Arabidopsis exhibits the developmental and physiological complexity typical of flowering plants, including perfect flowers (containing both male and female organs), simple leaves, trichomes, stomata, roots, root hairs, and vascular tissue [5]. This combination of experimental tractability and biological complexity creates an ideal bridge between molecular studies and whole-plant physiology, positioning Arabidopsis as a powerful model for understanding general plant principles.

The Arabidopsis Research Toolkit

The Arabidopsis research community has developed an extensive toolkit that greatly enhances its utility for systems biology. Genetic resources include large collections of sequence-indexed T-DNA insertion lines, with over 30,000 homozygous lines available through stock centers such as the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center and the Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre [5]. These resources enable reverse genetics approaches where researchers can identify lines with mutations in genes of interest and study their phenotypic consequences.

Advanced genome editing technologies, particularly CRISPR/Cas9, allow precise manipulation of the Arabidopsis genome [4] [5]. The well-established Agrobacterium-mediated transformation via floral dipping provides an efficient method for introducing foreign DNA without the need for tissue culture [5]. This technique has been instrumental in creating transgenic lines for functional genomics studies.

The availability of comprehensive 'omics' databases represents another cornerstone of the Arabidopsis toolkit. Resources such as The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR), Araport, and ePlant provide integrated genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data [5]. These platforms enable researchers to access and analyze large datasets, facilitating systems-level investigations. Additional specialized databases document protein-protein interactions, subcellular localization patterns, and post-translational modifications [5].

Table 2: Essential Research Resources for Arabidopsis Systems Biology

| Resource Category | Key Examples | Applications in Systems Biology |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Stocks | T-DNA insertion lines, EMS mutants [5] | Reverse genetics, functional analysis of specific genes |

| Full-Length cDNA | ABRC clone collections [5] | Protein expression, complementation tests, functional studies |

| Expression Vectors | Gateway-compatible vectors, yeast two-hybrid systems [5] | Protein localization, overexpression, interaction studies |

| Database Resources | TAIR, Araport, ePlant [5] | Data integration, bioinformatic analysis, hypothesis generation |

| Gene Expression Atlas | Tissue-specific transcriptome data [1] | Developmental genetics, regulatory network analysis |

The Arabidopsis research community has established standardized protocols for high-throughput phenotyping, with automated systems like the LemnaTec Scanalyzer enabling non-invasive monitoring of plant growth and development [3]. These systems employ multiple imaging modalities—including visible light (VIS), fluorescence (FLUO), and near-infrared (NIR)—to extract hundreds of phenotypic features simultaneously [3]. The integration of these diverse resources and methodologies creates a powerful infrastructure for systems biology research.

Arabidopsis in Systems Biology: Key Research Applications

Transcriptional Networks in Root Development

The Arabidopsis root has emerged as a premier model for studying transcriptional networks in development, offering exceptional advantages for spatiotemporal analysis. Root growth occurs primarily along radial and longitudinal axes through regulated division of stem cells, with cell differentiation following positional cues along the longitudinal axis [1]. This organized development enables researchers to correlate specific developmental stages with physical positions in the root.

Advanced technologies such as fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) of specific cell types have enabled the generation of high-resolution transcriptional maps [1]. One landmark study profiled gene expression across 14 root cell types and 13 longitudinal sections, creating the most comprehensive transcriptional atlas for any plant organ to date [1]. This approach revealed complex temporal regulation of gene expression, with many genes showing fluctuating patterns along developmental time rather than simple monotonic changes [1]. Coexpression analysis identified numerous transcriptional modules, including one for plant hormone biosynthesis that was supported by existing literature, while other modules provide novel frameworks for understanding the genetic regulation of developmental processes [1].

The integration of environmental response with developmental programs has been another fruitful area of Arabidopsis research. Studies examining the transcriptional response of different root tissues to salt stress and iron deficiency revealed dramatic cell-type-specific responses to environmental challenges [1]. Contrary to the hypothesis of a generalized stress response across cell types, these studies demonstrated that transcriptional responses are highly stimuli-specific, with relatively few genes responding to both stresses [1]. This cell-type-specific response strategy enables the root to partition functions among different tissues to optimize organ-level adaptation.

Metabolic Regulation and Stress Responses

Metabolites provide crucial insights into system function and response to perturbation, serving as measures of enzymatic activity over time and playing important roles in feedback regulation of transcriptional networks [1]. Arabidopsis research has revealed the tremendous chemical and enzymatic diversity in plants, with both primary metabolites (such as lipids and amino acids that function in fundamental cellular processes) and secondary metabolites (with more specialized functions often related to environmental adaptation) [1].

As sessile organisms, plants cannot escape unfavorable conditions and have evolved sophisticated metabolic adaptations for survival. Arabidopsis produces an array of specialized compounds including toxins for pathogen/herbivore defense, volatiles and pigments to attract pollinators, and various chemicals that provide salt or cold tolerance [1]. This metabolic diversity has practical significance for humans as well—approximately 12,000 distinct alkaloid compounds are predicted to be synthesized in plants, with about 2,000 having medical applications [1].

Recent systems biology studies have integrated metabolomic data with other 'omics' datasets to understand plant responses to environmental challenges. For example, quantitative proteomic analysis of Arabidopsis lines with different levels of Phospholipid:Diacylglycerol Acyltransferase1 (PDAT1) expression revealed that this enzyme, initially studied for its role in lipid metabolism, actually participates in broad stress response networks [6]. Overexpression of PDAT1 resulted in elevated levels of proteins involved in photoprotection, autophagy, and abiotic stress responses, while decreasing proteins involved in biotic stress responses [6]. These findings illustrate how systems approaches can reveal unexpected connections between metabolic enzymes and broader cellular response systems.

Modeling Cellular Patterning Through Gene Regulatory Networks

The Arabidopsis root epidermis has served as an ideal system for exploring how gene regulatory networks (GRNs) interact with diffusion dynamics to generate spatial patterns. The root epidermis establishes a distinctive organization with trichoblasts (root-hair cells) and atrichoblasts (non-hair cells) arranged in a specific pattern relative to underlying cortical cells [7]. Cells positioned over two cortical cells (H-position) typically adopt the root-hair cell fate, while those over a single cortical cell (N-position) become non-hair cells [7].

Central to this patterning process is a lateral inhibition mechanism mediated by the diffusion of CPC and GL3/EGL3 proteins, which coordinates cell identity decisions between neighboring cells [7]. In N-position cells, WEREWOLF (WER), GL3/EGL3, and TRANSPARENT TESTA GLABRA1 (TTG1) form a transcription activation complex that promotes GLABRA2 (GL2) expression, inhibiting root-hair development [7]. This complex also activates CAPRICE (CPC) expression, and the CPC protein diffuses to neighboring H-position cells, where it competes with WER to form an inhibitory complex that decreases GL2 expression and promotes root-hair differentiation [7].

Recent systems biology approaches have integrated these molecular interactions into meta-GRN models that simulate pattern formation through reaction-diffusion dynamics [7]. These models incorporate positive and negative feedback loops and explicitly simulate CPC and GL3/EGL3 protein diffusion between cells. By creating a 2-D morphospace or phenotypic landscape, researchers can predict epidermal patterning under varying diffusion levels and genetic perturbations, successfully recovering 28 single and multiple loss-of-function mutant phenotypes [7]. This approach demonstrates how complex spatial patterns emerge from the dynamic interplay between GRN topology and component diffusion.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

High-Throughput Plant Phenotyping

High-throughput phenotyping has become an essential methodology in plant systems biology, enabling quantitative monitoring of growth and development dynamics. The following protocol outlines the key steps for conducting phenotyping experiments with Arabidopsis, based on established methodologies [3]:

Plant Cultivation and Experimental Design:

- Seeds of Arabidopsis thaliana (e.g., genotype C248, NASC ID N22680) should be pre-treated on wet filter paper for one night (20°C, darkness) before sowing on soil mixture (75% Substrate 1, 15% sand)

- To initiate germination, pots with seeds undergo stratification for 3 days at 5°C in dark

- Germination should occur under controlled environmental conditions: long-day conditions (16h day/8h night) at 16/14°C, 75% relative humidity, and 120 μmol light intensity

- After 5 days, temperature should be increased to 20/18°C for the remaining cultivation period

- For experimental comparisons, include both moving (transported on conveyor belts) and stationary plants, as well as covered vs. uncovered soil treatments to assess potential methodological artifacts

Image Acquisition and Sensor Systems:

- Utilize automated phenotyping systems (e.g., LemnaTec Scanalyzer) for non-invasive image acquisition

- Acquire images daily from 12 days after sowing using multiple imaging modalities:

- Visible light (VIS) imaging: ~390-750 nm spectrum using RGB camera (e.g., Basler Pilot piA2400-17gc)

- Fluorescence imaging (FLUO): Excitation 400-500 nm, emission 520-750 nm using camera such as Basler Scout scA1400-17gc

- Near-infrared imaging (NIR): 1450-1550 nm range using monochrome camera sensor (e.g., Nir 300 PGE)

- Adjust zoom configurations for top-view images at different developmental stages (typically changing around 48 days after sowing)

- Acquire side images from multiple angles (0° and 90°) starting at later developmental stages (e.g., 48 days after sowing)

- Capture blank reference images (background without carrier and plants) before each imaging run

- Save all images as uncompressed PNG files to preserve data quality

Image Analysis and Feature Extraction:

- Process images using analysis platforms such as the Integrated Analysis Platform (IAP)

- Implement segmentation algorithms to distinguish plant pixels from background

- Extract approximately 310 features classified into geometric and color-related traits

- For biomass estimation, use formula: VLT = At × As.0° × As.90°, where At represents computed top area, and As.0° and As.90° represent computed side areas from different angles

- Perform pixel-to-mm conversion for geometric traits using pot and carrier as reference objects with known dimensions

Data Validation and Statistical Analysis:

- Collect manual measurements (e.g., plant height using ruler, dry weight after 3 days at 80°C) for validation

- Correct manually collected data for outliers based on ±2.5 standard deviations from the mean

- Perform correlation analysis between image-derived features and manual measurements using Pearson product-moment correlation with significance level of P<0.001

- Conduct ANOVA and post-hoc tests (e.g., Bonferroni) to assess statistical significance of observed differences

Proteomic Analysis of Genetic Manipulations

Proteomic analysis provides critical insights into how genetic manipulations affect cellular processes. The following protocol describes quantitative proteomic analysis of Arabidopsis lines with different levels of gene expression, based on recent methodologies [6]:

Plant Material and Growth Conditions:

- Use Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Columbia-0 (Col-0) as wild-type control

- Utilize transgenic lines (e.g., AtPDAT1-overexpressing lines OE1 and OE2) and knock-out lines (e.g., pdat1 KO)

- Sow seeds in soil and stratify at 4°C for 48 hours before transfer to growth chambers

- Grow plants under controlled conditions: constant temperature 22°C ± 1°C, 60% relative humidity, photoperiod of 16h light (120 µmol photons m⁻² s⁻¹)/8h darkness

- Collect leaf tissue samples (100 mg) when first flowers emerge (approximately 4.5 weeks after sowing)

- Immediately freeze samples in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C

Protein Extraction and Digestion:

- Homogenize 100 mg frozen leaf tissue with 250 mg glass beads (0.10-0.11 mm) using bead beater (10 × 20 s cycles), refreezing in liquid nitrogen between cycles to avoid thawing

- Precipitate proteins with ice-cold acetone containing 10% trichloroacetic acid and 0.07% β-mercaptoethanol, incubating overnight at -20°C

- Centrifuge at 5000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, then wash precipitate twice with acetone + 0.07% β-mercaptoethanol

- Dry precipitate under nitrogen stream and resuspend in extraction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 8 M urea, 1 mM dithiothreitol, protease inhibitor cocktail)

- Determine protein concentration using BCA assay

- For digestion, aliquot 60 µg protein, reduce with 20 mM dithiothreitol (30 min at 37°C), and alkylate with 60 mM iodoacetamide (30 min at 37°C in dark)

- Dilute urea to 1 M with 100 mM NH₄HCO₃ and digest with trypsin (2 µg) overnight at 37°C

LC-MS/MS Analysis and Data Processing:

- Analyze digested peptides using liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)

- Perform liquid chromatography with C18 column using gradient elution

- Acquire MS data in data-dependent acquisition mode, with full MS scans followed by MS/MS scans of the most intense ions

- Identify and quantify proteins using database search algorithms against Arabidopsis protein databases

- Process and statistically analyze data to identify significantly differentially expressed proteins between genotypes

Quantitative Data Synthesis

Table 3: High-Throughput Phenotyping Features Extracted from Arabidopsis Imaging [3]

| Feature Category | Number of Features | Example Parameters | Measurement Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| VIS-related Features | 139 | Projected leaf area, leaf perimeter, leaf count | Vegetative growth monitoring, morphological analysis |

| FLUO-related Features | 152 | Fluorescence intensity, photosynthetic efficiency | Photosynthetic performance, stress response |

| NIR-related Features | 17 | Water content indices, transpiration rates | Hydration status, water use efficiency |

| Geometric Traits | Not specified | Compactness, symmetry, center of mass | Architectural analysis, developmental patterning |

| Color-related Traits | Not specified | Hue, saturation, intensity values | Pigmentation analysis, health assessment |

Table 4: Mutation Effects on Quantitative Traits in Arabidopsis [8]

| Trait Category | Experimental Condition | Direction of Mutation Effects | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fitness Components | Field conditions (stressful) | Predominantly deleterious | Greater negative effects under field vs. growth room conditions |

| Fitness Components | Growth room (benign) | Approximately equal increase/decrease | Similar distribution to non-fitness traits in benign conditions |

| Non-fitness Traits | Growth room | Equal likelihood of increase/decrease | Bidirectional distribution consistent with neutral expectations |

| Survivorship | Field vs. growth room | Environment-dependent | Growth room survivorship >> field survivorship |

| Cumulative Effects | Multiple environments | Context-dependent | Highlights importance of measuring effects across environments |

Arabidopsis thaliana has proven its exceptional value as a model organism for plant systems biology, providing insights that extend far beyond its small stature. The lessons from Arabidopsis research demonstrate how a combination of experimental tractability and biological complexity can accelerate our understanding of fundamental biological principles. The systems biology approaches developed in Arabidopsis—including high-resolution transcriptional mapping, metabolic network analysis, and gene regulatory network modeling—are now being applied to crop species to address pressing agricultural challenges [1] [7].

The future of Arabidopsis systems biology lies in further refinement of spatiotemporal resolution in data collection, continued development of computational models that can accurately predict system behavior, and enhanced integration across multiple biological scales from molecules to ecosystems [1]. As these capabilities advance, Arabidopsis will continue to serve as a reference plant for deciphering the complex interactions between genes, environment, and phenotype. The powerful research toolkit and extensive community resources developed for Arabidopsis create a solid foundation for tackling increasingly complex biological questions, ensuring that this modest weed will remain at the forefront of plant systems biology for the foreseeable future.

In the field of plant systems biology, a fundamental challenge has been to move beyond static, organ-specific views of plant function toward a dynamic, system-wide understanding of development. Single-cell and spatial transcriptomic technologies are now enabling the construction of comprehensive cell atlases that provide unprecedented resolution of plant life cycles. These atlases represent a critical advancement in systems biology by allowing researchers to model how internal genetic programs and external environmental signals are integrated across different cell types, tissues, and developmental stages.

The model plant Arabidopsis thaliana has served as the foundational organism for pioneering these efforts, with recent studies generating complete transcriptomic atlases spanning its entire life cycle. These resources provide a systems-level view of plant development, capturing the molecular identities of hundreds of thousands of individual cells across multiple developmental stages, from seed to flowering adult [9] [10]. By applying computational frameworks from systems biology, researchers can now begin to model the complex regulatory networks that coordinate plant growth, development, and environmental responses at cellular resolution.

Technical Foundations: Methodologies for Plant Single-Cell and Spatial Transcriptomics

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Approaches

The creation of comprehensive plant cell atlases relies on two complementary technological approaches: single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq). Both methods enable the profiling of gene expression in individual cells, but they differ in their sample preparation requirements and applications.

Protoplast-based scRNA-seq involves enzymatic digestion of plant cell walls to isolate individual protoplasts, followed by capturing whole cells in droplets or wells for sequencing. This method captures RNA from both the cytoplasm and nucleus, providing a comprehensive view of the transcriptome. However, the enzymatic digestion process can induce stress responses that alter gene expression patterns, potentially skewing results for some cell types [11]. Additionally, cells with robust secondary cell walls, such as xylem vessels, are difficult to isolate intact using this method.

Single-nucleus RNA sequencing bypasses the need for cell wall digestion by directly isolating nuclei from plant tissues. This approach avoids protoplasting-induced stress responses and enables profiling of cell types that are difficult to digest enzymatically. snRNA-seq has proven particularly valuable for studying complex tissues like senescing leaves, flowers, and fruits, where protoplast isolation is challenging [12]. The main limitation is that snRNA-seq primarily captures nuclear transcripts, potentially underrepresenting cytoplasmic mRNAs.

Table 1: Comparison of Single-Cell Transcriptomics Approaches in Plants

| Feature | Protoplast-based scRNA-seq | Single-nucleus RNA-seq |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Input | Fresh tissues requiring enzymatic digestion | Fresh or frozen tissues |

| Transcript Coverage | Nuclear and cytoplasmic RNAs | Primarily nuclear RNAs |

| Cell Wall Concerns | Digestion may alter gene expression | No digestion required |

| Challenging Tissues | Limited for lignified or senescing tissues | Effective for diverse tissue types |

| Spatial Context | Lost during protoplasting | Lost during nuclei isolation |

| Representation Bias | May underrepresent hard-to-digest cells | More uniform across cell types |

Spatial Transcriptomics Technologies

A significant limitation of both scRNA-seq and snRNA-seq is the loss of spatial context during tissue dissociation. Spatial transcriptomics addresses this limitation by preserving the native architecture of plant tissues while capturing transcriptome-wide gene expression data. These technologies use barcoded spots on slides or in situ sequencing to assign expression profiles to specific spatial coordinates within a tissue section [9] [10].

The integration of single-cell/single-nucleus data with spatial transcriptomics creates a powerful framework for mapping gene expression to specific cell types and locations within tissues. This paired approach has been successfully applied to multiple Arabidopsis organs, including roots, leaves, stems, flowers, and siliques, enabling the validation of cell-type-specific markers and the discovery of spatially restricted expression patterns [10].

Experimental Workflow for Comprehensive Atlas Generation

The generation of a complete plant cell atlas requires careful experimental design and execution across multiple stages:

Diagram 1: Experimental Workflow for Plant Cell Atlas

Sample Collection Strategy

Comprehensive atlases require sampling across the entire life cycle. The Salk Institute atlas, for example, captured ten developmental stages of Arabidopsis thaliana, from imbibed seeds through germinating seeds, three seedling stages, developing and mature rosettes, stems, flowers, and developing siliques [9] [10]. This temporal coverage enables analysis of developmental trajectories and transitional states.

Data Generation and Analysis Pipeline

Following sample collection, the workflow involves:

- Nuclei/Protoplast Isolation: Using optimized protocols to maintain RNA integrity while obtaining single-cell suspensions.

- Library Preparation: Employing high-throughput methods such as 10x Genomics or plate-based protocols (SMART-seq2).

- Sequencing: Generating sufficient depth to detect low-abundance transcripts across hundreds of thousands of cells.

- Bioinformatic Processing: Using tools like Cell Ranger, Seurat, or SCANPY for quality control, normalization, and clustering.

- Cell Type Annotation: Mapping clusters to known cell types using marker genes and spatial validation.

- Data Integration: Combining datasets from multiple stages and organs into a unified reference atlas.

Case Study: The Arabidopsis Thaliana Life Cycle Atlas

Atlas Scope and Scale

A landmark study published in Nature Plants in 2025 established the most comprehensive Arabidopsis cell atlas to date, profiling over 400,000 cells across ten developmental stages using paired single-nucleus and spatial transcriptomics [9] [10]. This resource encompasses all major organ systems and tissues, from seeds to developing siliques, providing unprecedented resolution of the plant life cycle.

The atlas identified 183 distinct cell clusters across all datasets, with researchers successfully annotating 75% (138 clusters) to specific cell types and states [10]. This annotation was facilitated by the development of a curated marker gene database and spatial validation of expression patterns.

Table 2: Quantitative Overview of the Arabidopsis Life Cycle Atlas

| Parameter | Specification |

|---|---|

| Developmental Stages | 10 (from seed to flowering adult) |

| Total Cells Profiled | >400,000 |

| Identified Clusters | 183 |

| Annotated Clusters | 138 (75%) |

| Sequencing Technology | Single-nucleus RNA-seq + Spatial Transcriptomics |

| Spatial Validation | Multiple organs (root, leaf, stem, flower, silique) |

| Key Discoveries | Novel seedpod development genes, dynamic transcriptional programs |

Technical Achievements and Methodological Innovations

The Arabidopsis life cycle atlas demonstrates several technical advances in plant single-cell genomics:

Integrated Analysis Framework: The study implemented a computational pipeline for jointly analyzing data across developmental stages while accounting for batch effects and biological variation. This enabled the identification of conserved transcriptional signatures across recurrent cell types as well as organ-specific heterogeneity [10].

Spatial Validation of Novel Markers: The paired spatial transcriptomic data allowed researchers to validate 109 newly identified cell-type-specific and tissue-specific marker genes across all organs [10]. This confirmation is crucial for accurate cell type annotation and functional studies.

Resolution of Cellular States: Beyond identifying cell types, the atlas captured transient cellular states associated with developmental progression and hormonal regulation. For example, detailed spatial profiling of the apical hook structure revealed complex patterns of gene expression underlying this transient developmental structure [10].

Biological Insights from the Life Cycle Atlas

The comprehensive nature of this atlas has enabled several fundamental insights into plant biology:

Dynamic Regulation of Development: By examining the full life cycle rather than isolated snapshots, researchers identified surprisingly dynamic and complex regulatory networks controlling plant development [9]. This temporal perspective reveals how transcriptional programs are rewired across development.

Novel Gene Discovery: The study identified numerous previously uncharacterized genes with cell-type-specific expression patterns, including genes involved in seedpod development that had not been previously associated with this process [9]. These discoveries provide new candidates for functional characterization.

Cellular Heterogeneity Mapping: The atlas revealed striking molecular diversity in cell types and states across development, highlighting the previously underappreciated complexity of plant tissues [10]. For instance, the study identified organ-specific heterogeneity in epidermal cells, challenging the assumption of uniform identity across tissues.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Plant Cell Atlas Construction

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Platforms for Plant Single-Cell Genomics

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Application in Plant Studies |

|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Chromium | Droplet-based single-cell partitioning | High-throughput scRNA-seq of plant protoplasts and nuclei |

| SMART-seq2 | Plate-based full-length scRNA-seq | Higher sensitivity for low-abundance transcripts |

| DNBelab C Series | Single-cell library preparation | snRNA-seq of diverse plant tissues |

| Cell Ranger | scRNA-seq data processing | Generation of expression matrices from raw sequencing data |

| Seurat/SCANPY | Single-cell data analysis | Clustering, visualization, and differential expression |

| Spatial Transcriptomics | Slide-based spatial mapping | Validation of cell-type localization and discovery of spatial patterns |

| Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) | Nuclei purification | Isolation of high-quality nuclei from complex tissues |

Computational Analysis Framework for Atlas Data

Data Processing and Integration

The analysis of single-cell and spatial transcriptomics data requires a sophisticated computational workflow:

Diagram 2: Computational Analysis Pipeline

Advanced Analytical Approaches

Beyond basic clustering and annotation, comprehensive atlases enable more sophisticated analyses:

Trajectory Inference: Pseudotime algorithms can reconstruct developmental trajectories, ordering cells along continuous processes such as differentiation or senescence. For example, a complementary study on leaf senescence used single-nucleus data to track the progression of aging states at cellular resolution [12].

Gene Regulatory Network Inference: By analyzing co-expression patterns across thousands of cells, researchers can infer regulatory relationships between transcription factors and their potential targets. These networks provide insights into the control mechanisms underlying cell identity and state transitions.

Cross-Species Comparison: Integrating data from multiple species can identify conserved and divergent cellular programs. While most comprehensive atlases currently exist for Arabidopsis, similar approaches are being applied to crop species, enabling comparative analyses [11].

Integration with Systems Biology Models

From Atlas Data to Predictive Models

The true power of comprehensive cell atlases lies in their integration with systems biology approaches to develop predictive models of plant development. These atlases provide the foundational data for:

Multi-scale Models: Connecting molecular events at the cellular level to tissue-level phenotypes and organismal outcomes. For instance, single-cell data on hormone response networks can be integrated with models of organ growth and development.

Environmental Response Modeling: Capturing how different cell types respond to environmental signals enables more accurate prediction of whole-plant responses to stress. Systems biology approaches like those developed by the Coruzzi Lab for nitrogen signaling can be enhanced with cell-type-specific resolution [13].

Foundation Models for Plant Biology: Recent advances in foundation models (FMs) trained on large-scale biological data present opportunities for leveraging atlas data. Plant-specific FMs such as GPN, AgroNT, and PlantCaduceus address challenges unique to plant genomes, including polyploidy and high repetitive sequence content [14]. These models can be fine-tuned on single-cell data to improve their performance on cell-type-specific prediction tasks.

Applications in Crop Improvement

The insights gained from Arabidopsis cell atlases provide a template for similar efforts in crop species, with direct applications for agricultural improvement:

Trait Discovery: Identifying cell-type-specific expression patterns associated with desirable traits can accelerate marker-assisted breeding. For example, understanding root cell-type responses to nutrient availability could inform breeding for more efficient nutrient uptake.

Precision Breeding: Synthetic biology approaches, including synthetic gene circuits, can leverage cell-type-specific promoters identified in atlases to precisely control gene expression in target tissues [15]. This enables more sophisticated engineering of complex traits.

Stress Resilience: Mapping how different cell types respond to abiotic and biotic stresses can identify key regulatory hubs for enhancing resilience. This systems-level understanding moves beyond single-gene approaches to target entire regulatory modules.

Future Directions and Challenges

While comprehensive cell atlases represent a major advance in plant systems biology, several challenges and opportunities remain:

Multi-omics Integration: Current atlases primarily focus on transcriptomics. Future efforts will benefit from integrating epigenomic (e.g., single-cell ATAC-seq), proteomic, and metabolomic data to build more comprehensive models of cellular states.

Dynamic Perturbation Responses: Capturing how cell-type-specific responses change under genetic and environmental perturbations will enhance the predictive power of models derived from atlas data.

Computational Tool Development: As atlas data grows in scale and complexity, new computational methods will be needed for integration, visualization, and analysis. Foundation models trained on these datasets may enable new capabilities for prediction and design.

Cross-Species Consortia: Expanding atlas efforts to diverse plant species will enable comparative analyses to identify conserved and divergent cellular programs, with implications for both basic plant biology and crop improvement.

In conclusion, comprehensive cell atlases profiling entire plant life cycles with single-cell and spatial transcriptomics represent a transformative resource for plant systems biology. By providing high-resolution maps of cellular states across development and integrating this information with computational modeling approaches, these atlases enable a more predictive understanding of plant development and function. As these resources continue to expand and integrate with other data modalities, they will play an increasingly central role in both basic plant research and agricultural innovation.

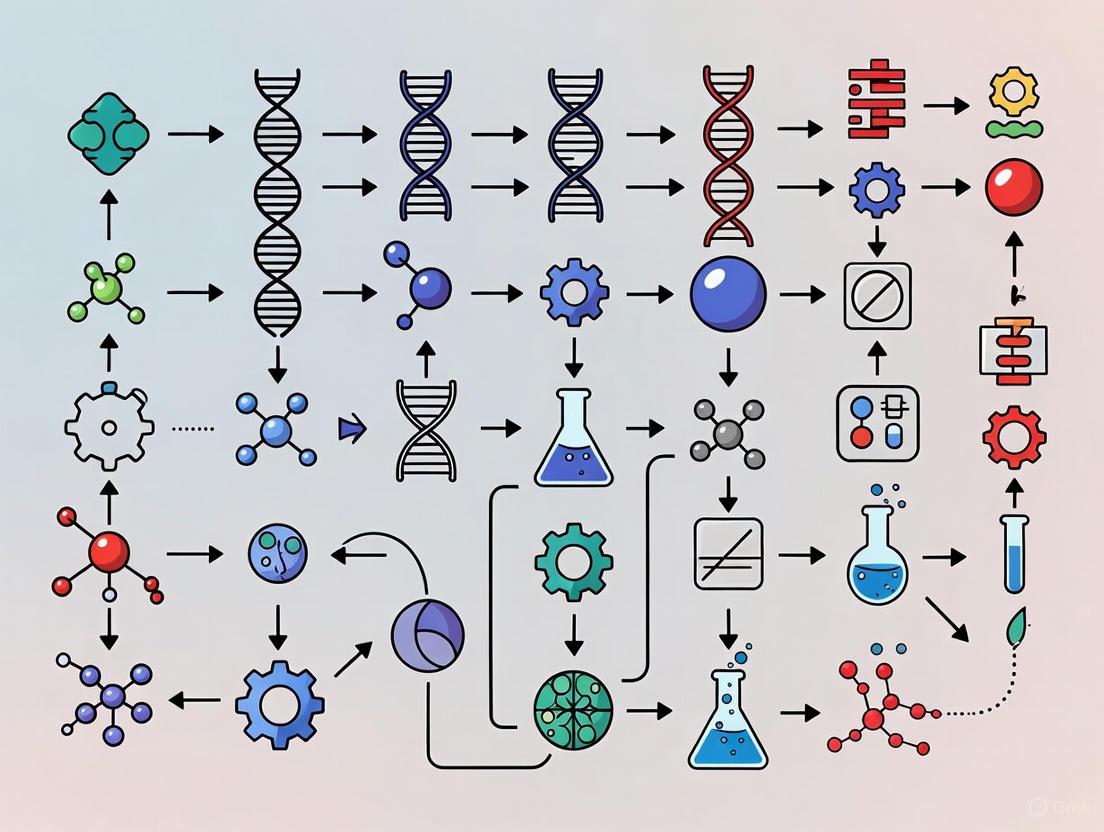

In plant development research, a fundamental challenge has been bridging the gap between static observational data and the inherently dynamic nature of biological systems. Traditional static network models provide snapshots of gene regulatory relations at a single time point or unions of successive regulations over time. While simpler to construct and interpret, these models crucially ignore temporal aspects of gene regulations such as the order of interactions and their pace, which are essential for understanding developmental processes [16]. The emerging paradigm in systems biology shifts from these static snapshots to dynamic network models that can capture how regulatory relations change over time, thus offering a more accurate representation of biological reality. This shift is particularly relevant for plant research, where development is continuously shaped by complex interactions between genetic programs and environmental factors [9] [14].

This technical guide explores both the theoretical foundations and practical methodologies for inferring dynamic regulatory interactions from static experimental data, with specific application to plant systems biology. We examine how computational approaches can extract temporal information from cross-sectional data, how advanced sequencing technologies enable more comprehensive network mapping, and how foundation models are revolutionizing our ability to predict regulatory dynamics in plant development.

Theoretical Foundations: From Correlation to Causation in Temporal Data

The Challenge of Inferring Dynamics from Static Data

The core challenge in reconstructing dynamic networks from static data lies in distinguishing mere correlation from causal regulatory relationships. When only single time-point measurements are available, researchers must rely on statistical patterns of co-variability to infer potential regulatory connections. A key insight from theoretical work shows that static population snapshots of co-variability can be rigorously exploited to infer properties of gene expression dynamics when gene expression reporters probe their upstream dynamics on separate time-scales [17]. This approach can be experimentally exploited in dual-reporter experiments with fluorescent proteins of unequal maturation times, effectively turning an experimental limitation into an analytical feature [17].

For time-series data, the inference of dynamic relationships becomes more tractable. The fundamental principle involves identifying consistent temporal relationships between regulator and target genes. A gene involved in regulatory interactions with others has at least one activator or inhibitor, where an activator initiates transcription of the gene, making high-level expression impossible without such regulation [16]. By analyzing the sequence and timing of expression changes across multiple genes, researchers can reconstruct the causal relationships that drive developmental processes.

Mathematical Frameworks for Dynamic Inference

The inference of dynamic regulatory relationships from time-series gene expression data typically employs modified correlation measures that incorporate temporal dimensions. The modified Pearson correlation coefficient R1(X,Y,i,p) represents the correlation between gene X at time point i and gene Y at time point i+p, where p is the time span of the gene regulation [16]. This approach can identify four fundamental types of gene regulatory relations:

- +A(t₁) → +B(t₂): Up-regulation of A at time t₁ is followed by up-regulation of B at time t₂ (t₂ > t₁)

- -A(t₁) → +B(t₂): Down-regulation of A at time t₁ is followed by up-regulation of B at time t₂ (t₂ > t₁)

- +A(t₁) → -B(t₂): Up-regulation of A at time t₁ is followed by down-regulation of B at time t₂ (t₂ > t₁)

- -A(t₁) → -B(t₂): Down-regulation of A at time t₁ is followed by down-regulation of B at time t₂ (t₂ > t₁) [16]

However, correlation-based measures alone cannot distinguish gene regulatory relations with the same correlation but different expression levels. Therefore, an additional Euclidean distance score R2 is often employed to account for magnitude differences in expression patterns [16]. This two-score system provides a more robust foundation for identifying genuine regulatory relationships.

Table 1: Scoring Metrics for Inferring Gene Regulatory Relationships

| Metric | Formula | Application | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modified Pearson Correlation (R1) | R1(X,Y,i,p) = ∑k=1N(Xk - X̄)(Yk - Ȳ) / √[∑k=1N(Xk - X̄)²∑k=1N(Yk - Ȳ)²] | Identifies temporal relationships between genes | Positive R1: ActivationNegative R1: Inhibition |

| Euclidean Distance Score (R2) | R2(X,Y) =√[∑k=1N(Xk - X̄)² + ∑k=1N(Yk - Ȳ)²] | Distinguishes relations with same correlation but different expression levels | R2 < 3: Activation likelyR2 > 6: Inhibition likely |

Technological Advances Enabling Dynamic Network Reconstruction

Single-Cell and Spatial Transcriptomics in Plant Research

Recent technological breakthroughs have dramatically enhanced our ability to map regulatory networks across complete developmental timelines. The integration of single-cell RNA sequencing with spatial transcriptomics has been particularly transformative for plant research. While single-cell RNA sequencing reveals which genes are active in individual cells, spatial transcriptomics preserves the anatomical context, showing where these cells are located within the plant and how they interact with their neighbors [9].

This combined approach has enabled the creation of comprehensive atlases spanning entire life cycles of model plants. For example, researchers have recently established the first genetic atlas to span the entire Arabidopsis life cycle, capturing gene expression patterns of 400,000 cells across 10 developmental stages—from seed to flowering adulthood [9]. This resource reveals a surprisingly dynamic and complex cast of characters responsible for regulating plant development and has already led to discoveries of previously unknown genes involved in seedpod development [9]. The ability to track gene expression at cellular resolution across a complete developmental timeline represents a quantum leap in our capacity to infer dynamic regulatory networks.

Foundation Models for Plant Molecular Biology

The emergence of foundation models (FMs) trained on large-scale biological data represents another major advance for decoding regulatory dynamics in plants. These neural networks, trained using self-supervised learning on massive datasets, can adapt to a wide range of downstream tasks in plant molecular biology [14]. Unlike general biological FMs trained primarily on human or animal data, plant-specific FMs such as GPN, AgroNT, PDLLMs, PlantCaduceus, and PlantRNA-FM address challenges specific to plant genomes, including polyploidy, high repetitive sequence content, and environment-responsive regulatory elements [14].

These models operate across multiple biological levels:

- DNA-level FMs (e.g., DNABERT, Nucleotide Transformer) identify regulatory elements and model long-range dependencies in DNA sequences [14]

- RNA-level FMs (e.g., RNA-FM, SpliceBERT) unravel relationships among RNA sequences, structures, and functions [14]

- Protein-level FMs (e.g., ESM, SaProt) revolutionize structural prediction and functional analysis [14]

- Single-cell-level FMs bridge cellular mechanisms with tissue-level phenotypes through transcriptomic and epigenetic modeling [14]

The capability of these models to process multi-modal data and capture long-range dependencies in biological sequences makes them particularly valuable for inferring dynamic regulatory interactions from static snapshots.

Experimental Protocols for Dynamic Network Inference

Time-Series Gene Expression Analysis Protocol

For inferring dynamic regulatory interactions from time-series gene expression data, the following protocol provides a robust methodology:

Sample Collection and Data Generation:

- Collect gene expression data for m genes with n time points, represented as an m × n matrix where rows represent genes and columns represent sequential time points in a biological process

- Ensure sufficient temporal resolution to capture relevant biological processes—for plant development studies, this may require sampling across multiple developmental stages

- Use appropriate normalization techniques to account for technical variation while preserving biological signals

Regulatory Relationship Identification:

- Compute R1(A,B,t₁,p) between gene A at time point t₁ and gene B at time point t₁+p for all gene pairs

- Select the regulation with the largest absolute value of R1(A,B,t₁,p) for each candidate pair

- For relationships where 0 < p < 6 (where p represents a biologically plausible time span), classify the regulation into one of the four fundamental types and add to the regulation list

- Compute R2 scores for gene pairs in the regulation list to distinguish relations with similar correlation but different expression magnitudes

- Iterate until no additional significant regulations are identified [16]

Validation and Network Construction:

- Apply false discovery rate correction for multiple hypothesis testing

- Validate key predicted interactions through experimental approaches such as perturbation studies

- Construct dynamic network models that represent temporal aspects of regulatory interactions

Static Snapshot Analysis Using Dual-Reporter Systems

When only static snapshots are available, the following protocol enables inference of dynamic properties:

Experimental Design:

- Implement dual-reporter systems with fluorescent proteins of unequal maturation times

- Ensure reporters probe upstream dynamics on separate time-scales

- Collect single-cell expression data across a population of cells at a single time point

Data Analysis:

- Analyze covariance patterns in expression variability across the cell population

- Apply correlation conditions that detect the presence of closed-loop feedback regulation

- Identify genes with cell-cycle dependent transcription rates from variability patterns of co-regulated fluorescent proteins [17]

- Use statistical inference to reconstruct likely dynamic relationships from population-level variation

Computational Implementation and Workflow

The process of inferring dynamic networks from experimental data involves multiple computational steps that transform raw data into biological insights. The following diagram visualizes this comprehensive workflow:

Network Dynamics and Link Reciprocity

In dynamic network models, the concept of link reciprocity plays a crucial role in maintaining stability and function. Unlike behavioral reciprocity where actions toward others depend on their past actions, link reciprocity involves creating or dissolving network ties in response to partners' behaviors [18]. This mechanism is particularly important in biological networks where interactions may change based on functional needs.

Experimental evidence demonstrates that the frequency of network updating significantly impacts functional outcomes. In rapidly updating networks, cooperators preferentially break links with defectors and form new links with cooperators, creating incentives for cooperation and leading to substantial changes in network structure [18]. This principle translates to biological contexts where molecular interactions may be reconfigured based on functional requirements and cellular context.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Dynamic Network Analysis

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Technologies | Single-cell RNA sequencing | Cell-type specific expression profiling | Resolves cellular heterogeneityReveals rare cell populations |

| Spatial transcriptomics | Context-preserving gene expression mapping | Maintains anatomical relationshipsEnables tissue-level analysis | |

| Computational Tools | GeneNetFinder | Dynamic network inference from time-series data | Implements R1/R2 scoring systemVisualizes temporal properties [16] |

| Plant-specific Foundation Models (GPN, AgroNT, etc.) | Prediction of regulatory interactions | Addresses plant-specific challengesHandles polyploid genomes [14] | |

| Experimental Resources | Arabidopsis Life Cycle Atlas | Reference for developmental gene expression | 400,000 cells across 10 stagesPublicly available online resource [9] |

| Dual-reporter systems with fluorescent proteins | Inferring dynamics from static snapshots | Unequal maturation timesProbe upstream dynamics [17] | |

| Model Organisms | Arabidopsis thaliana | Reference plant for developmental studies | Extensive existing knowledge baseGenetic tractability [9] |

Signaling Pathways and Regulatory Logic in Plant Development

The following diagram illustrates a generalized regulatory network for plant development, showing key interactions and feedback loops:

Interpretation of Regulatory Logic

The regulatory network illustrates how plant development emerges from the interaction between environmental signals and genetic programs. Environmental factors (light, temperature, nutrients) influence master regulator genes that initiate transcriptional cascades. These regulators activate hormone signaling pathways that control cellular differentization processes, ultimately establishing tissue identity. Critical feedback mechanisms modulate the activity of master regulators, creating dynamic balance that allows adaptation to changing conditions.

This network structure explains how plants achieve developmental plasticity while maintaining overall organizational integrity. The presence of both forward activation and feedback inhibition creates a system that can respond to environmental cues while stabilizing developmental trajectories—a crucial capability for sessile organisms that cannot relocate to avoid unfavorable conditions.

The transition from static snapshots to dynamic networks represents a paradigm shift in how we study regulatory interactions in plant development. While static networks provide simplified models that are easier to construct and interpret, they fundamentally cannot capture the temporal aspects of gene regulation that are essential for understanding developmental processes. The integration of advanced technologies—particularly single-cell and spatial transcriptomics combined with foundation models—is rapidly overcoming previous limitations and enabling reconstruction of truly dynamic regulatory networks.

Future progress in this field will likely focus on several key areas: improved integration of multi-modal data, development of more sophisticated temporal inference algorithms, and creation of plant-specific foundation models that better account for the unique characteristics of plant genomes. As these methodologies mature, they will increasingly enable researchers to not only understand but also predict and engineer plant developmental processes, with significant implications for agriculture, biotechnology, and basic plant biology research.

Systems biology represents a fundamental shift in biological research, moving from a traditional reductionist focus on individual components to an integrative approach that seeks to understand how these components interact to form functional networks. In plant biology, this framework is particularly powerful for decoding the complex mechanisms underlying development, stress responses, and nutrient use efficiency. The core paradigm of systems biology is an iterative cycle of computational model generation and experimental validation, which progressively refines our understanding of biological systems. This approach allows researchers to transition from descriptive observations to predictive models that can simulate plant behavior under various genetic and environmental conditions. By framing biological questions in terms of systems-level properties, researchers can identify emergent behaviors that cannot be explained by studying individual molecules or pathways in isolation.

The foundational premise of systems biology is that biological systems are more than the sum of their parts. In plant development, this perspective is essential for understanding how molecular networks coordinate processes such as root architecture patterning, photoperiod sensing, and floral transition. The integration of multi-omics data—genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—within a systems biology framework has enabled unprecedented insights into the regulatory logic of plants. This methodology is particularly valuable for addressing grand challenges in plant science, including improving nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) and developing climate-resilient crops, by providing a computational platform to simulate and test breeding strategies before field implementation.

The Core Iterative Cycle: Data Integration and Model Refinement

The systems biology approach is fundamentally cyclical, comprising four key phases that form an iterative loop: (1) experimental data generation, (2) computational model construction, (3) model-based prediction and simulation, and (4) experimental validation and refinement. Each cycle enhances the model's predictive power and biological relevance, gradually uncovering the design principles of the system under study.

Phase 1: Comprehensive Data Generation - The initial phase involves generating high-quality, multidimensional datasets that capture the system's state across different conditions and time points. Recent advances in single-cell technologies have revolutionized this step by enabling resolution at the level of individual cells. For instance, a recent landmark study established a foundational atlas of the plant life cycle for Arabidopsis thaliana using detailed single-cell and spatial transcriptomics, capturing the gene expression patterns of 400,000 cells across ten developmental stages [9]. This spatial transcriptomics approach preserves the anatomical context of cells, providing insights into gene expression patterns within the native tissue architecture rather than in isolated cell suspensions.

Phase 2: Computational Model Construction - In this phase, heterogeneous datasets are integrated to construct mathematical models that represent the structure and dynamics of the biological system. Network models are particularly effective for representing interactions between molecular components. The Coruzzi Lab at NYU has developed VirtualPlant, a software platform specifically designed for plant systems biology that enables researchers to analyze genomic data within network models of plant biology [13]. These models can range from qualitative network diagrams to quantitative kinetic models that simulate the rate of biological processes.

Phase 3: Model-Based Prediction and Simulation - Once constructed, models are used to simulate system behavior under novel conditions and generate testable hypotheses. For example, models of nitrogen regulatory networks can predict how perturbations to specific transcription factors affect root development and nutrient assimilation pathways [13]. Foundation models (FMs) in biology represent a recent breakthrough in this phase, with neural networks trained on large-scale datasets that can adapt to various downstream tasks including prediction of gene function and regulatory relationships [14].

Phase 4: Experimental Validation and Refinement - Model predictions are tested through targeted experiments, and the resulting data are used to refine the model parameters and structure. This critical step ensures that computational models remain grounded in biological reality. Discrepancies between predictions and experimental outcomes often lead to new biological insights and model improvements, initiating another cycle of iteration.

Key Technological Drivers and Methodologies

Advanced Omics Technologies

The power of systems biology depends fundamentally on the quality and comprehensiveness of the data fed into computational models. Several advanced technologies have dramatically enhanced our ability to characterize biological systems at multiple levels.

Single-Cell and Spatial Transcriptomics: Traditional bulk RNA sequencing measures average gene expression across thousands or millions of cells, obscuring cell-to-cell variation. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) resolves this by profiling gene expression in individual cells, revealing cellular heterogeneity and identifying rare cell types. When combined with spatial transcriptomics, which preserves the geographical context of cells within tissues, researchers can map gene expression patterns to specific anatomical locations. The Arabidopsis life cycle atlas exemplifies this approach, capturing developmental trajectories across 400,000 individual cells from seed to flowering plant [9]. This technological synergy enables the identification of novel genes involved in specific developmental processes, such as seedpod development, within their native tissue context.

Foundation Models for Biological Sequences: Inspired by advances in natural language processing (NLP), foundation models (FMs) are neural networks trained on massive-scale biological datasets using self-supervised learning. These models capture complex patterns in biological sequences—DNA, RNA, and proteins—and can be adapted to various prediction tasks with minimal fine-tuning. For plant sciences, specialized FMs are emerging to address genome-specific challenges including polyploidy, high repetitive sequence content, and environment-responsive regulatory elements [14]. Plant-specific FMs such as GPN, AgroNT, PDLLMs, PlantCaduceus, and PlantRNA-FM are designed to handle these unique aspects of plant genomes that are not adequately addressed by models trained on human or animal data.

Computational and Modeling Frameworks

Network Analysis Platforms: VirtualPlant, developed by the Coruzzi Lab, exemplifies specialized software platforms that enable systems biology approaches across the plant research community [13]. Such platforms provide intuitive interfaces for biologists to explore genomic data within the context of regulatory networks, metabolic pathways, and other biological systems. They typically integrate data from multiple sources and allow users to visualize relationships between molecular components, identify enriched functional categories, and generate testable hypotheses about network behavior.

Multi-Scale Integration Tools: A significant challenge in systems biology is integrating data across different biological scales—from molecular interactions to cellular responses to tissue-level phenotypes. Computational frameworks that facilitate this integration are essential for comprehensive modeling. The "BigPlant" phylogenomic framework represents one such approach, comprising 22,833 sets of orthologs from 150 plant species, which enables researchers to identify overrepresented functional gene categories at major nodes in seed plant phylogeny [13]. This evolutionary perspective helps prioritize key genes and biological processes for further experimental investigation.

Application in Plant Nitrogen Use Efficiency (NUE)

Nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) provides an illustrative case study of the systems biology approach applied to a critical agricultural trait. The Coruzzi Lab has developed systems biology approaches to predictively model how internal and external perturbations affect processes, pathways, and networks controlling plant growth and development, with particular emphasis on NUE [13]. Their research has uncovered regulatory networks that coordinate a plant's response to sensing nitrogen sources in its environment and internal nitrogen status.

These studies have identified key hubs in N-regulatory networks that coordinate nitrogen regulation of metabolic processes (N-assimilation), cellular processes (circadian rhythm), and developmental processes (N-foraging in roots) [13]. This systems view reveals how plants optimize nitrogen utilization through coordinated responses across multiple biological scales. For example, the integration of nitrogen signaling with circadian regulation allows plants to temporally separate nitrogen assimilation from photosynthesis, minimizing photorespiratory losses. Similarly, the connection between nitrogen availability and root development enables plants to adjust their root architecture to forage more effectively for nitrogen sources in the soil.

Table 1: Key Network Components in Plant Nitrogen Use Efficiency

| Network Component | Biological Process | Systems-Level Function |

|---|---|---|

| N-Assimilation Hubs | Metabolic processing | Convert inorganic nitrogen to organic forms |

| Circadian Regulators | Cellular rhythm | Temporally coordinate nitrogen metabolism with photosynthesis |

| Root Development Factors | Organ development | Modulate root architecture for nitrogen foraging |

| Transcription Factors | Gene regulation | Integrate nitrogen signals with developmental programs |

Experimental Protocols for Systems Biology

Protocol Reporting Standards

Reproducibility is essential for systems biology, as models depend on reliable experimental data. A guideline for reporting experimental protocols in life sciences proposes 17 fundamental data elements that facilitate protocol execution and reproducibility [19]. These elements include detailed descriptions of reagents, equipment, experimental parameters, and step-by-step procedures that ensure other researchers can replicate experiments exactly. Such standardization is particularly crucial in systems biology, where computational models often integrate data from multiple experimental sources performed by different research groups.

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Workflow

The creation of a comprehensive plant cell atlas requires standardized methodologies for single-cell and spatial transcriptomics. Below is a generalized workflow based on the approach used to generate the Arabidopsis life cycle atlas:

Sample Preparation: Tissues are collected from plants at specific developmental stages and immediately processed to preserve RNA integrity. For spatial transcriptomics, tissues are often embedded in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound and flash-frozen to maintain spatial organization.

Cell Dissociation and Isolation: Tissues are dissociated into single-cell suspensions using enzymatic and mechanical methods that minimize cellular stress and RNA degradation. Viability and cell quality are assessed before proceeding to library preparation.

Library Preparation and Sequencing: Single-cell RNA sequencing libraries are prepared using platforms such as the 10x Genomics Chromium system, which barcodes individual cells, enabling pooled sequencing while maintaining cell identity. For spatial transcriptomics, tissues are mounted on specialized slides that capture location-specific barcodes.

Data Processing and Analysis: Raw sequencing data undergoes quality control, alignment to the reference genome, and normalization. Dimensionality reduction techniques such as UMAP or t-SNE are applied to visualize cellular clusters, and differential expression analysis identifies marker genes for distinct cell types.

Diagram 1: Single-Cell Transcriptomics Workflow. The process flows from sample preparation (yellow) through wet-lab procedures (green) to computational analysis (blue).

Network Inference and Validation

Constructing gene regulatory networks from transcriptomic data follows a standardized computational workflow:

Data Integration: Transcriptomic datasets from multiple conditions or time points are integrated and normalized to account for technical variation.

Network Inference: Computational algorithms such as mutual information, correlation measures, or Bayesian networks are applied to identify potential regulatory relationships between transcription factors and target genes.

Network Validation: Predicted regulatory interactions are validated through targeted experiments, including chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) to confirm physical binding, and mutant analysis to test functional relationships.

Model Refinement: Validation results are incorporated to refine the network model, improving its predictive accuracy for subsequent cycles of hypothesis generation.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in Systems Biology |

|---|---|---|

| Model Organisms | Arabidopsis thaliana | Reference plant for foundational studies [9] |

| Software Platforms | VirtualPlant [13] | Network analysis and data integration |

| Omics Technologies | Single-cell RNA sequencing [9] | Cellular resolution of gene expression |

| Foundation Models | PlantCaduceus, AgroNT [14] | Prediction of gene function and regulation |

| Data Repositories | Nature Protocol Exchange [19] | Access to standardized experimental protocols |

Foundational Computational Models in Plant Systems Biology

Multi-Level Foundation Models

Foundation models represent a transformative development in biological computation, with specialized versions emerging for plant research. These models operate across multiple biological scales:

DNA-Level FMs: Models such as DNABERT and Nucleotide Transformer identify regulatory elements in DNA sequences by adapting natural language processing techniques. These models use k-mer tokenization or byte pair encoding to segment DNA sequences into analyzable units, enabling prediction of promoter regions, enhancers, and protein-binding sites [14]. For plant genomes with high repetitive content, specialized models like GPN-MSA incorporate multi-species alignment data to enhance prediction of functional variants.

RNA-Level FMs: RNA foundation models including RNA-FM and SpliceBERT analyze RNA sequences to predict structure, splicing patterns, and functional elements. PlantRNA-FM addresses plant-specific challenges such as environment-responsive regulatory elements [14]. These models help decipher how RNA processing contributes to developmental regulation in plants.

Protein-Level FMs: Protein foundation models such as the ESM (Evolutionary Scale Modeling) series and ProtTrans learn from evolutionary conserved patterns in protein sequences to predict structure and function. For plants, these models can predict how sequence variations affect protein function in different developmental contexts [14].

Single-Cell FMs: Models for single-cell transcriptomics data can identify cell types, predict developmental trajectories, and infer gene regulatory networks. These are particularly valuable for understanding plant development at cellular resolution.

Diagram 2: Multi-Level Biological Foundation Models. Specialized models at different molecular levels contribute to an integrated understanding of plant systems.

Plant-Specific Modeling Challenges and Solutions

Plant systems biology faces unique challenges that require specialized computational approaches:

Polyploidy and Genome Complexity: Many crop plants, including wheat and cotton, are polyploid, containing multiple sets of chromosomes. This complexity creates challenges for genomic analysis and network modeling. Solutions include specialized foundation models trained on polyploid genomes and comparative approaches that leverage evolutionary relationships.

Environment-Responsive Regulation: Plant gene expression is highly responsive to environmental conditions, requiring models that incorporate environmental parameters. The Coruzzi Lab's research on nitrogen regulatory networks exemplifies how systems biology can decode these environment-gene interactions [13].

Limited and Heterogeneous Data: Compared to human and model animal systems, plant genomics suffers from more limited and heterogeneous datasets. Transfer learning approaches, where models pre-trained on well-characterized organisms are fine-tuned for specific plants, help overcome this limitation.

The future of systems biology in plant research will be shaped by several emerging trends and technological developments. Increased integration of multi-omics data across temporal and spatial scales will provide more comprehensive views of plant development and responses. The development of more sophisticated foundation models specifically trained on plant data will enhance our ability to predict gene function and regulatory relationships [14]. Additionally, the incorporation of environmental variables into systems models will improve predictions of plant performance under field conditions.

The iterative cycle of data and modeling will continue to drive advances in plant systems biology, with each revolution in measurement technology enabling more refined computational models. As single-cell technologies advance to include spatial proteomics and metabolomics, and as computational methods incorporate more sophisticated deep learning architectures, our ability to model and predict plant development will reach unprecedented levels of accuracy and utility.

This iterative systems biology approach—moving from descriptive observations to predictive models—represents a powerful framework for addressing fundamental questions in plant development and for designing improved crop varieties to meet future agricultural challenges. By continuing to refine both experimental and computational methodologies, plant systems biologists are building a comprehensive understanding of plants as integrated systems, from molecular interactions to organismal phenotypes.

The Modeler's Toolkit: Methodological Approaches from Gene Circuits to Whole-Plant Architectures

Computational modeling serves as an indispensable tool for understanding the complex dynamics of plant development, from molecular interactions within a single cell to organ-level growth patterns. In plant systems biology, computational techniques are broadly categorized into two complementary paradigms: pattern models and mechanistic mathematical models [20]. This distinction is not merely technical but fundamental to the research questions each approach can address. Pattern models, including statistical and machine learning approaches, are primarily data-driven and excel at identifying correlations and patterns within large datasets. Conversely, mechanistic mathematical models are hypothesis-driven, seeking to encapsulate the underlying biological processes, chemical reactions, and physical principles that govern system behavior [20]. The strategic selection between these approaches depends on multiple factors including the research objective, available data, and the desired level of biological interpretation.

Defining the Modeling Paradigms

Pattern Recognition Models

Pattern models are primarily utilized to discover spatial, temporal, or relational patterns between system components, such as genes, proteins, or entire plants [20]. These models are inherently "data-driven," built on mathematical representations that incorporate assumptions about data structure and statistical properties. They draw from disciplines including bioinformatics, statistics, and machine learning [20]. In practice, pattern models are deployed for tasks such as genome annotation, phenomics, and the analysis of proteomic and metabolomic data. Techniques like dimensionality reduction (e.g., clustering of gene expression data), latent feature extraction, and neural networks are commonly employed to manage and interpret large-scale biological datasets [20].

Key Applications in Plant Research:

- Gene Expression Analysis: Software such as DESeq2 uses generalized linear models with a negative binomial distribution to identify genes whose expression changes significantly under different treatment conditions [20].

- Trait-Gene Mapping: Pattern modeling integrates molecular data (e.g., transcript abundance) with physiological phenotypes to predict causal genes underlying agriculturally important traits through correlation analysis, as seen in transcriptome-wide association studies (TWAS) [20].

- Time-Series and Single-Cell Data: Methods like weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) and tools such as Seurat or Monocle help identify functionally correlated transcripts from time-series data or track cell development trajectories at single-cell resolution [20].

Mechanistic Mathematical Models

Mechanistic mathematical models describe the underlying chemical, biophysical, and mathematical properties of a biological system to predict and understand its behavior from a cause-and-effect perspective [20]. These models formalize hypotheses about core biological processes—such as biochemical reactions, hormone signaling, and mechanical forces—into a mathematical framework, often using ordinary differential equations (ODEs) or logical networks [21] [20]. A critical principle in mechanistic modeling is parsimony, which prioritizes the simplest set of necessary components and processes needed to explain the system's behavior [20]. This simplification is itself a knowledge-generating exercise, helping to isolate the fundamental principles governing complex phenomena.

Key Applications in Plant Research:

- Understanding Non-linear Dynamics: Mechanistic models can explore the non-linear relationships that often underlie plant adaptation and behavior, which are frequently missed by correlation-focused pattern models [20].

- Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs): While pattern models can infer static GRN structures, mechanistic models simulate their temporal dynamics. This allows researchers to study how interactions between transcription factors and genes control processes like spatial tissue patterning and stress responses [20].

- Integrating Growth and Mechanics: A major frontier involves combining molecular patterning with models of mechanical properties and forces to understand morphogenesis—how plants actually acquire their shape [22]. This includes simulating how turgor pressure and anisotropic cell wall properties guide growth [22].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Pattern vs. Mechanistic Models

| Feature | Pattern Recognition Models | Mechanistic Mathematical Models |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Identify correlations, clusters, and patterns in data [20] | Understand and simulate underlying processes and causality [20] |

| Foundation | Data-driven; relies on statistical assumptions [20] | Hypothesis-driven; based on biological/chemical principles [20] |

| Typical Outputs | Correlation coefficients, cluster assignments, predictive classifications | System dynamics over time, responses to perturbations, emergent properties |

| Model Parsimony | Not always a primary concern (e.g., large neural nets) [20] | A central objective; models balance realism with simplicity [20] |