Maximizing Precision: A Guide to Base Editing Efficiency Factors in Plants for Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the key factors influencing CRISPR base editing efficiency in plants.

Maximizing Precision: A Guide to Base Editing Efficiency Factors in Plants for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the key factors influencing CRISPR base editing efficiency in plants. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational mechanisms of plant base editors, details methodological best practices for achieving high-efficiency edits, offers troubleshooting strategies for common challenges, and presents comparative frameworks for validation. The guide synthesizes current knowledge to empower the reliable use of plant base editing in developing novel therapeutics and research models.

Understanding the Core: Mechanisms and Components of Plant Base Editors

Base editing represents a revolutionary advance in precision genome editing, enabling the direct, irreversible conversion of one target DNA base pair to another without requiring double-stranded DNA breaks (DSBs) or donor DNA templates. This article frames the technology within the critical research context of optimizing base editing efficiency factors in plants, where outcomes are directly influenced by the choice of editor, delivery method, and cellular context.

Core Technology: From CRISPR-Cas9 to Chemical Conversion

Base editors are fusion proteins that couple a catalytically impaired CRISPR-Cas nuclease (e.g., Cas9 nickase, dCas9) with a nucleobase deaminase enzyme. The system is guided by a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) to a target genomic locus, where the deaminase performs a precise chemical conversion on a single DNA strand.

Key Classes:

- Cytosine Base Editors (CBEs): Convert C•G to T•A. They fuse a cytidine deaminase (e.g., rAPOBEC1) to dCas9 or nCas9. An uracil glycosylase inhibitor (UGI) is often included to prevent uracil excision repair.

- Adenine Base Editors (ABEs): Convert A•T to G•C. They use an engineered adenine deaminase (e.g., TadA-8e) fused to nCas9.

Experimental Protocol: A Standard Workflow for Plant Base Editing

This protocol outlines a common Agrobacterium-mediated transformation approach for evaluating base editing efficiency in dicot plants (e.g., Nicotiana benthamiana, Arabidopsis).

1. Construct Design and Assembly:

- Select the appropriate base editor (BE3 for CBE, ABE8e for high-efficiency adenine editing).

- Clone the BE expression cassette (driven by a plant promoter like AtU6-26 for sgRNA and 35S for the BE protein) into a binary T-DNA vector.

- Design the sgRNA to place the target base within the deaminase activity window (typically positions 4-8 for SpCas9-derived BEs, counting the PAM as 21-23).

2. Plant Transformation:

- Introduce the binary vector into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101.

- For N. benthamiana, perform leaf disk infiltration. For Arabidopsis, use the floral dip method.

- Select transformed plants on appropriate antibiotic/media.

3. Analysis of Editing Efficiency:

- Harvest leaf tissue from T0 or T1 plants.

- Extract genomic DNA and PCR-amplify the target region.

- Analyze products via Sanger sequencing followed by decomposition tracing (using tools like BEAT or EditR) or next-generation sequencing (NGS) for high-throughput quantification of editing efficiency and byproduct profiles (indels, unintended edits).

Diagram Title: Plant Base Editing Experimental Workflow

Key Efficiency Factors in Plant Research

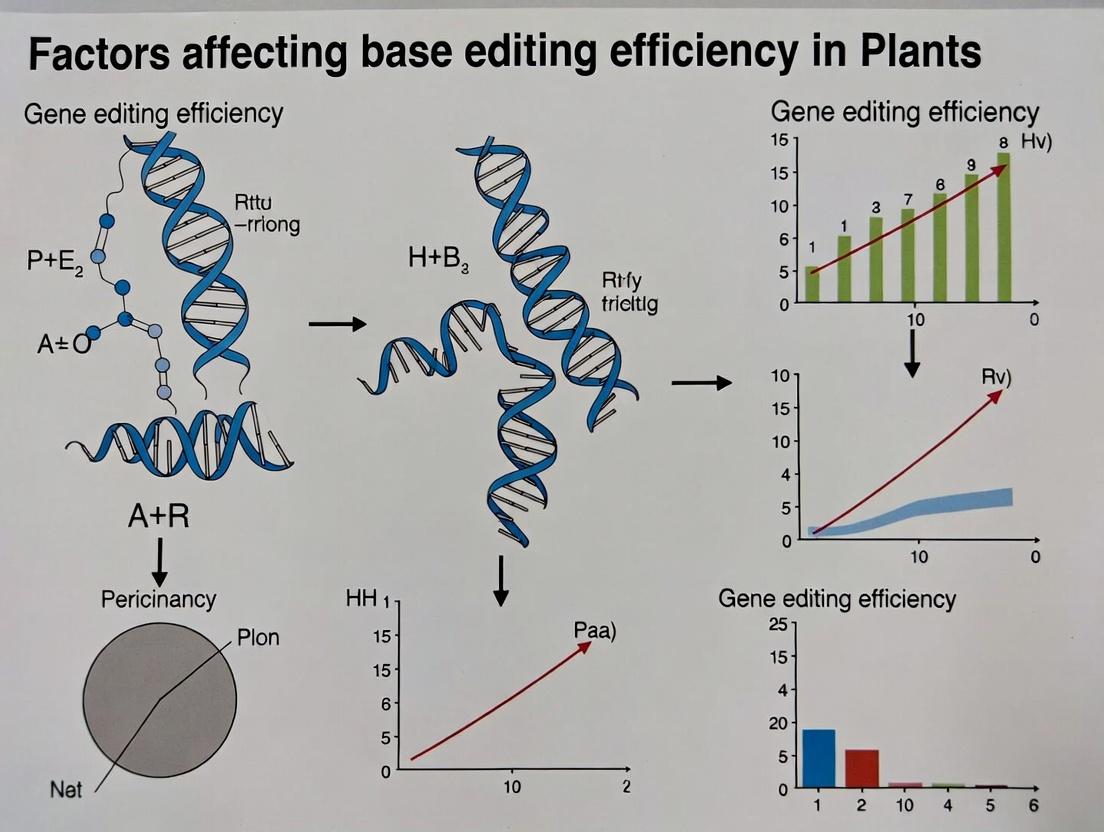

Efficiency in plants is governed by multiple interdependent factors, as summarized in the quantitative data table below.

Table 1: Key Factors Influencing Base Editing Efficiency in Plants

| Factor | Typical Experimental Range/Options | Observed Impact on Efficiency (Representative Data) | Key Considerations for Plants |

|---|---|---|---|

| Base Editor Version | BE3, BE4, ABE7.10, ABE8e | ABE8e shows 5-10x higher efficiency than ABE7.10 in rice protoplasts. | Newer versions (BE4, ABE8e) reduce indels & improve product purity. |

| Promoter Strength | 35S, AtUbi10, OsActin, Yao | AtUbi10 drove 2.3x higher editing than 35S in wheat callus. | Strong, constitutive promoters often needed for robust expression. |

| sgRNA Design | Spacing to PAM (positions 4-10) | Optimal window: positions 4-8 for CBE; 75% efficiency drop outside window. | Plant codon-optimized sgRNAs with high on-target scores are critical. |

| Delivery Method | Agrobacterium, RNP, PEG | RNP delivery to protoplasts achieved 65% editing vs. 22% via T-DNA. | Agrobacterium is standard for stables; RNPs for transient assays. |

| Plant Species/Cell Type | Protoplasts, Callus, Meristems | Editing in rice callus: ~40%; regeneration to T0 plants: ~15%. | Regeneration efficiency can bottleneck observed plant-level editing. |

| Chromatin State | Open vs. Closed regions | Editing in euchromatin can be 3-5x higher than in heterochromatin. | Epigenetic modifiers co-delivery is an emerging optimization strategy. |

Diagram Title: Interdependent Factors Affecting Plant Editing Efficiency

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Plant Base Editing Research

| Reagent / Material | Function & Role in Research | Example Product/Catalog |

|---|---|---|

| Modular Base Editor Plasmids | Pre-assembled vectors for easy cloning of plant-specific BEs (CBE, ABE). | pCBC-DT1T2 (CBE) from Addgene; pRDA-ABE8e plant binary vector. |

| Plant Codon-Optimized Cas9 Variants | High-efficiency nCas9 (D10A) backbone for BE fusions, optimized for plant expression. | pCambia-nCas9-PmCDA1 (for CBE assembly). |

| U6/7 Polymerase III Promoter Vectors | For driving high-level sgRNA expression in plant cells. | AtU6-26 or OsU3 promoter-containing entry vectors. |

| Agrobacterium Strains | For stable or transient plant transformation. | GV3101 (for dicots), EHA105 (for monocots). |

| Plant DNA Isolation Kits | High-quality gDNA extraction for PCR and sequencing analysis. | CTAB-based methods or commercial kits (e.g., DNeasy Plant). |

| NGS Library Prep Kits for Amplicons | Quantify editing efficiency and byproducts at high depth and accuracy. | Illumina TruSeq Custom Amplicon; iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix for initial PCR. |

| Edit Deconvolution Software | Calculate base editing percentages from Sanger sequencing traces. | BEAT (https://github.com/), EditR (https://github.com/). |

Within the context of base editing efficiency factors in plant research, the optimization of core molecular components is paramount. Base editors (BEs) are fusion proteins that combine a catalytically impaired Cas nuclease with a nucleobase deaminase enzyme, enabling precise, targeted point mutations without generating double-strand breaks. This technical guide details the critical elements—deaminases, Cas9 variants, and plant-optimized constructs—that determine the efficacy, specificity, and applicability of base editing in plant systems.

Deaminase Enzymes: Function and Engineering

Deaminases are the active components that catalyze the chemical conversion of one nucleobase to another. Their origin, processivity, and window of activity are primary determinants of editing efficiency and product purity.

Cytosine Base Editor (CBE) Deaminases

CBEs use cytidine deaminases (e.g., APOBEC1, hAID, CDA1) to convert C•G to T•A.

- APOBEC1: The most widely used, often from rat (rAPOBEC1). It exhibits high activity but can cause significant off-target RNA editing.

- Engineering for Plant Systems: Plant codon-optimization is essential. Furthermore, engineered variants like SECURE (e.g., rAPOBEC1-R33A) reduce unwanted RNA editing while maintaining DNA editing activity.

Adenine Base Editor (ABE) Deaminases

ABEs use engineered tRNA-specific adenosine deaminase (TadA) derived from E. coli to convert A•T to G•C.

- TadA*: A heterodimer of wild-type TadA and an evolved, high-activity monomer (e.g., TadA-8e, TadA-8e(V106W)). Continuous evolution has produced versions (up to TadA-8.20m) with enhanced activity and specificity.

Key Performance Metrics

Deaminase choice impacts:

- Editing Window: The region within the protospacer where deamination occurs efficiently (typically positions 3-10 for CBEs, 4-10 for ABEs, using 1-based indexing from the PAM-distal end).

- Processivity: Tendency for multiple C-to-T or A-to-G conversions within a single binding event.

- Product Purity: Ratio of desired pure product to unwanted byproducts (e.g., indels, other base transversions).

Table 1: Characteristics of Common Deaminase Enzymes in Plant Base Editing

| Deaminase | Base Editor Type | Origin | Key Features in Plants | Potential Drawbacks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rAPOBEC1 | CBE | Rat | High DNA editing efficiency; well-characterized. | High RNA off-target activity; narrow window. |

| hAPOBEC3A | CBE | Human | Ultra-narrow window (positions 5-7); high purity. | Lower efficiency in some plant contexts. |

| hAID | CBE | Human | Broad window; moderate efficiency. | Can be more error-prone. |

| CDA1 | CBE | Sea Lamprey | Lower RNA off-target activity than rAPOBEC1. | Generally lower editing efficiency. |

| TadA-8e | ABE | Engineered E. coli | High A-to-G efficiency; minimal RNA off-targets. | Requires heterodimer formation. |

| TadA-9e | ABE | Engineered E. coli | Improved version of TadA-8e. | May have altered window in plants. |

Cas9 Variants: Defining Targeting and Precision

The Cas9 component provides DNA targeting via guide RNA (gRNA) complementarity and influences editing window, off-target effects, and PAM compatibility.

Nickase Cas9 (nCas9)

The standard backbone for most BEs. A D10A mutation inactivates the RuvC nuclease domain, leaving the HNH domain active to create a single-strand nick in the non-edited strand. This nick biases cellular repair to use the edited strand as a template, enhancing efficiency.

High-Fidelity and PAM-Expanded Variants

- SpCas9-HF1/eSpCas9(1.1): Engineered to reduce non-specific DNA binding, thereby decreasing DNA off-target editing.

- SpCas9-NG: Recognizes an NG PAM, significantly expanding the targeting space compared to the canonical NGG PAM of wild-type SpCas9.

- xCas9: Recognizes a broad range of PAMs (NG, GAA, GAT).

- SaCas9 & SaCas9-KKH: Smaller size, useful for viral delivery; recognizes NNGRRT or NNNRRT PAMs.

- ScCas9: Very small size; recognizes NNG PAM.

Table 2: Cas9 Variants for Plant Base Editing

| Cas9 Variant | PAM | Size (aa) | Key Advantage | Consideration for Plants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SpCas9-D10A (nCas9) | NGG | ~1368 | Standard; high efficiency. | Limited by NGG PAM frequency. |

| SpCas9-NG | NG | ~1368 | ~4x more targetable sites than NGG. | Slightly lower efficiency than SpCas9. |

| xCas9(3.7) | NG, GAA, GAT | ~1368 | Broad PAM recognition. | Editing efficiency can be highly variable. |

| SaCas9-D10A (nSaCas9) | NNGRRT | ~1053 | Compact; good for size-limited vectors. | Lower efficiency than SpCas9 in many plants. |

| ScCas9-D10A (nScCas9) | NNG | ~1003 | Very compact; NG PAM. | Newer variant; plant performance under evaluation. |

Plant-Specific Constructs and Delivery Optimization

Effective expression in plants requires specialized genetic constructs and delivery methods tailored to plant cell biology.

Expression Cassette Design

- Promoters: Strong, constitutive promoters like CaMV 35S (dicots) or ZmUbi (maize) are common. Tissue-specific or inducible promoters can provide spatiotemporal control.

- Codon Optimization: Gene sequences must be optimized for the nuclear codon usage of the target plant species (e.g., Arabidopsis, rice, tomato).

- Subcellular Localization: Addition of a Nuclear Localization Signal (NLS) (often bipartite for BEs) is critical to direct the protein to the genome.

- Linker Design: The peptide linker between deaminase and Cas9 affects stability and editing window. Common linkers include (GGGGS)ₙ sequences.

- Terminators: Effective polyadenylation signals like NOS or 35S terminator are used.

Delivery Methods

- Agrobacterium-mediated Transformation (T-DNA): Most common for stable transformation. The BE expression cassette(s) are cloned between T-DNA borders.

- PEG-mediated Protoplast Transfection: For rapid testing of BE performance in a species.

- Biolistic Particle Delivery: Used for monocots and species recalcitrant to Agrobacterium.

- Viral Vectors (e.g., Bean Yellow Dwarf Virus): For transient, high-copy delivery, potentially increasing editing efficiency but not for stable inheritance.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Base Editing Efficiency in Protoplasts

Purpose: Rapid, quantitative evaluation of a new BE construct in plant cells. Materials: Plant tissue, cell wall digesting enzymes, PEG solution, BE plasmid DNA. Steps:

- Isolate protoplasts from leaf mesophyll tissue using enzymatic digestion (e.g., Cellulase R10, Macerozyme R10).

- Purify protoplasts via filtration and flotation in W5 or Mannitol solution.

- Transfect 10-20 µg of BE plasmid DNA (with gRNA expression cassette) into ~10⁵ protoplasts using PEG 4000.

- Incubate in the dark for 48-72 hours to allow expression and editing.

- Harvest protoplasts, extract genomic DNA.

- PCR-amplify the target region and analyze editing efficiency via next-generation sequencing (NGS) or restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) if editing disrupts a site.

Protocol 2: Stable Plant Transformation and Screening

Purpose: Generate stably edited plant lines. Materials: Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain (e.g., GV3101), binary vector with BE, plant explants, selection antibiotics. Steps:

- Clone the BE expression cassette (Promoter::BE-NLS::Terminator) and a separate gRNA expression cassette (U6/U3 promoter::gRNA scaffold) into a T-DNA binary vector.

- Transform the vector into Agrobacterium.

- Inoculate plant explants (e.g., leaf discs, cotyledons, immature embryos) with the Agrobacterium culture.

- Co-cultivate for 2-3 days, then transfer to callus induction/regeneration media with antibiotics to select for transformed tissue and eliminate Agrobacterium.

- Regenerate shoots and root them to generate T0 plants.

- Extract DNA from leaf tissue, screen for edits by PCR/sequencing. Analyze segregation in T1 generation to identify non-transgenic, edited plants.

Visualizations

(Diagram Title: Plant Base Editing Experimental Workflow)

(Diagram Title: Base Editor Architecture and Mechanism)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Plant Base Editing Research

| Item | Function | Example/Supplier |

|---|---|---|

| Modular Cloning System (e.g., Golden Gate, MoClo) | Enables rapid, standardized assembly of BE components (promoter, deaminase, Cas9 variant, NLS, terminator, gRNA). | Plant MoClo Toolkit (Weber et al.). |

| Plant-Optimized Codon Sequences | Synthetic genes for deaminases and Cas9 variants optimized for expression in target species (e.g., Arabidopsis, rice, wheat). | Custom synthesis from IDT, GenScript, Twist Bioscience. |

| Binary Vectors for Agrobacterium | T-DNA vectors with plant selection markers (e.g., hygromycin, basta/glufosinate resistance). | pCAMBIA, pGreen, pORE series. |

| gRNA Cloning Vector | A vector containing a plant RNA Pol III promoter (U6, U3) and gRNA scaffold for easy insertion of target sequences. | pYLgRNA (CRISPR-GE toolkit). |

| High-Efficiency Agrobacterium Strain | Optimized for plant transformation. | GV3101, EHA105, AGL1. |

| Protoplast Isolation Enzymes | Enzyme mixes for digesting plant cell walls to release protoplasts. | Cellulase R10, Macerozyme R10 (Yakult). |

| PEG Transfection Solution | Polyethylene glycol solution for inducing DNA uptake into protoplasts. | PEG 4000, 40% solution. |

| High-Fidelity PCR Kit | For error-free amplification of target loci from genomic DNA for sequencing analysis. | Q5 (NEB), KAPA HiFi (Roche). |

| Next-Generation Sequencing Kit | For deep sequencing of PCR-amplified target sites to quantify editing efficiency and outcomes. | Illumina TruSeq, iTru primers. |

| DNA Gel Extraction Kit | For purification of DNA fragments during cloning. | QIAquick (Qiagen), Monarch (NEB). |

| Plant Tissue Culture Media | Sterile, formulated media for callus induction, regeneration, and rooting of transformed tissues. | MS (Murashige & Skoog) Basal Salts. |

Base editing in plants represents a transformative approach for precise genetic modification, enabling targeted conversion of single nucleotides without generating double-strand breaks. However, the unique architecture of plant cells—characterized by a rigid polysaccharide cell wall and a complex organelle landscape—poses significant barriers to editing efficiency. This whitepaper examines the primary physical and biological factors limiting base editor delivery and activity, framed within the broader thesis that overcoming these cellular hurdles is the key to unlocking robust, predictable plant genome engineering.

Key Efficiency-Limiting Factors: Data Synthesis

Recent studies (2023-2024) quantify the impact of cellular structures on editing outcomes. Data are synthesized from live searches of current literature in Nature Plants, Plant Biotechnology Journal, and Plant Cell Reports.

Table 1: Quantified Impact of Plant Cell Structures on Base Editing Efficiency

| Factor | Typical Measurement | Impact on Editing Efficiency (Range) | Key Study Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Wall Permeability | PEG-mediated transformation efficiency | 40-60% reduction vs. protoplasts | Nicotiana benthamiana |

| Organelle Sequestration | Nuclear localization signal (NLS) efficiency | NLS-fused editors: 70-80% nuclear; Without NLS: <10% | Arabidopsis thaliana protoplasts |

| Chloroplast DNA Off-target | Editing ratio (Nuclear:Chloroplast) | Cas9-derived editors: Up to 1:0.5; TALE-based: 1:0.01 | Oryza sativa (Rice) |

| Vacuole Size/Activity | Editor half-life in cytoplasm | Reduction of active editor by ~50% in highly vacuolated cells | Solanum tuberosum (Potato) |

| Cytosolic Nuclease Activity | Degradation rate of mRNA editor templates | mRNA template half-life: 2-4 hours | Zea mays (Maize) |

Table 2: Efficiency of Delivery Methods Across Cell Barriers

| Delivery Method | Approximate Max. Efficiency (Stable Transformation) | Primary Limiting Cell Structure | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| PEG-mediated (Protoplasts) | 60-80% (transient) | N/A (Wall removed) | Bypasses cell wall |

| Agrobacterium-mediated (T-DNA) | 1-30% (stable) | Cell wall & nuclear envelope | Whole tissue applicable |

| Biolistics (Gene Gun) | 5-20% (stable) | Cell wall & organelle membranes | Bypasses biological barriers |

| Carbon Nanotubes | 15-40% (transient) | Cell wall & plasma membrane | Rapid cytoplasmic delivery |

| Virus-Induced Genome Editing (VIGE) | 10-90% (transient, systemic) | Plasmodesmata size exclusion | Systemic spread |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Assessing Cell Wall Impact via Protoplast Comparison

Objective: Quantify the isolated impact of the cell wall on base editor delivery by comparing editing rates in intact cells versus protoplasts.

- Material Preparation: Generate two identical aliquots of plant tissue (e.g., leaf mesophyll from N. benthamiana).

- Protoplast Isolation: Digest one aliquot with an enzyme solution (1.5% Cellulase R-10, 0.4% Macerozyme R-10 in 0.4M mannitol, pH 5.7) for 3-6 hours. Purify protoplasts via centrifugation (100xg) and washing.

- Parallel Delivery: Deliver the same base editor construct (e.g., adenine base editor (ABE) mRNA) and targeting guide RNA to both intact tissue (via biolistics) and purified protoplasts (via PEG-mediated transfection).

- Analysis: After 48-72 hours, extract genomic DNA from both samples. Use targeted deep sequencing (amplification of the target locus) to calculate the percentage of edited reads. The efficiency difference quantifies the wall's barrier effect.

Protocol: Evaluating Nuclear Import Efficiency

Objective: Determine the role of nuclear localization signals (NLS) in overcoming nuclear envelope sequestration.

- Construct Design: Create two base editor (BE) constructs: one with a C-terminal tandem NLS (e.g., 2xSV40 NLS) and one without any NLS.

- Transient Expression: Co-transfect both constructs separately into plant protoplasts along with a nuclear marker (e.g., H2B-mCherry).

- Subcellular Fractionation: At 24h post-transfection, isolate nuclei using differential centrifugation (lysis buffer with non-ionic detergent, then 2000xg pellet).

- Quantification: Perform Western blot on cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions using anti-Cas9 antibodies. Calculate the nuclear:cytoplasmic fluorescence ratio via confocal microscopy for NLS vs. non-NLS fusions.

Visualization of Pathways and Workflows

Diagram Title: Plant Cell Barriers to Base Editor Delivery

Diagram Title: Protoplast-Based Base Editing Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Plant Base Editing Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Macerozyme & Cellulase R-10 | Enzymatic digestion of cell wall for protoplast isolation. | Batch variability requires optimization for each plant species/tissue. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) 4000 | Induces membrane fusion for DNA/RNP delivery into protoplasts. | Molecular weight and concentration are critical for viability. |

| Gold/Carrier Microcarriers | Coating for biolistic delivery (gene gun) into intact tissues. | Particle size (0.6-1.0 µm) dictates penetration depth. |

| Tandem Nuclear Localization Signals (2xSV40 NLS) | Enhances nuclear import of base editor proteins. | Essential for efficient targeting of nuclear DNA; position affects activity. |

| Plasmid pCambia-ABE8e | Common plant expression vector for adenine base editors. | Contains plant-specific promoter (e.g., 2x35S) and terminator. |

| Guide RNA Scaffold (tRNA-gRNA) | Expression system for improved gRNA processing in plants. | Enhances gRNA accumulation vs. Pol III promoters. |

| Mannitol Solution (0.4-0.6M) | Osmoticum for protoplast stabilization post-isolation. | Maintains tonicity to prevent lysis. |

| LC-MS Grade Phenol | For high-quality RNA-free genomic DNA extraction post-editing. | Purity is critical for downstream sequencing applications. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing Kit (e.g., Illumina MiSeq) | Targeted amplicon sequencing to quantify editing efficiency. | Requires high coverage (>5000x) for accurate low-frequency detection. |

| Anti-Cas9 Monoclonal Antibody | Detection of base editor protein localization via Western/fluorescence. | Confirms expression and can assess degradation. |

Within the broader thesis on base editing efficiency factors in plant research, three core metrics stand as critical quantitative endpoints: Editing Frequency, Purity, and Inheritance Rates. These parameters collectively define the success and practical applicability of a base editing experiment, from initial transformation to the establishment of stable, non-transgenic lines. This guide provides a technical deep dive into the definition, measurement, and optimization of these pivotal metrics.

Defining the Core Metrics

Editing Frequency: The percentage of cells or primary transformants (T0) in which the intended base conversion is detected at the target site. It reflects the initial activity and delivery efficiency of the base editing system.

Editing Purity: The proportion of edited alleles that contain only the desired base change without unintended edits (e.g., indels, bystander edits within the editing window, or transversions). It is a measure of precision.

Inheritance Rate: The frequency at which the edited allele is stably transmitted to the next generation (T1 and beyond), following Mendelian or non-Mendelian segregation patterns, and the efficiency of obtaining transgene-free edited plants.

The following tables consolidate recent data (2023-2024) from key studies in plant base editing, highlighting the impact of different editor systems, promoters, and delivery methods on the core metrics.

Table 1: Influence of Base Editor System on Efficiency in Plants

| Base Editor System (Plant) | Target | Avg. Editing Frequency (T0) | Avg. Purity (% Desired Product) | Key Findings | Citation (Example) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rAPOBEC1-Cas9n-UGI (A->G) Rice | OsALS | 43.2% | 61.5% | High frequency but notable bystander C->T edits. | Li et al., 2023 |

| eA3A-Cas9n-UGI (C->T) Tomato | SIPDS | 26.8% | 89.7% | Improved purity profile with engineered deaminase. | Ren et al., 2024 |

| TadA-8e-Cas9n (A->G) Wheat | TaALS | 64.1% | 72.3% | Very high activity; some RNA off-target effects noted. | Wang et al., 2023 |

| CGBE1 (C->G) Arabidopsis | AtRPS5a | 18.9% | 45.2% | Lower efficiency and purity highlight technical challenges. | Sretenovic et al., 2024 |

Table 2: Effect of Promoter and Delivery Method on Metrics

| Experimental Factor | Editing Frequency | Purity | Inheritance (T1, edited/transgene-free) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Promoter: Egg cell-specific pDD45 | Moderate | High | Very High | Efficient germline editing, favors heritable edits. |

| Promoter: Constitutive pUbiquitin | Very High | Lower | Moderate | High somatic editing, more chimerism, complex segregation. |

| Delivery: Agrobacterium (T-DNA) | High | High | Standard | Standard for many dicots; random integration. |

| Delivery: Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) | Low-Moderate | Very High | High | Transient activity, significantly reduces transgene integration. |

| Delivery: Viral (e.g., BSMV) | Very High (local) | Low | Very Low | Systemic infection, highly mosaic, rarely heritable. |

Experimental Protocols for Measurement

Protocol 1: Amplicon Sequencing for Editing Frequency and Purity

Objective: Quantify base conversion efficiency and byproduct spectrum at the target locus.

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Harvest leaf tissue from T0 plants or pooled calli. Use a CTAB-based method.

- PCR Amplification: Design primers flanking the target site (~250-350 bp product). Use a high-fidelity polymerase.

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Purify PCR products. Use overhang adapters for Illumina sequencing. Aim for >50,000x read depth per sample.

- Data Analysis:

- Editing Frequency:

(Number of reads with target base conversion / Total reads) * 100. - Editing Purity:

(Reads with only the intended conversion / All edited reads) * 100. - Byproduct Analysis: Quantify percentage of reads containing indels or other base substitutions.

- Editing Frequency:

Protocol 2: Segregation Analysis for Inheritance Rates

Objective: Determine transmission of edited alleles to T1 and identify transgene-free plants.

- T1 Population Generation: Self-pollinate primary (T0) edited plants. Harvest seeds individually.

- Genotyping:

- Germination: Grow ~20-30 T1 seedlings per T0 line.

- PCR Assays: Perform two parallel PCRs from each seedling: a) Target Site Amplification: Sequence to identify heterozygous/homozygous edited alleles. b) Transgene Detection: Amplify a segment of the Cas9/deaminase gene or selectable marker.

- Data Calculation:

- Inheritance Rate:

(Number of T1 plants carrying the edit / Total T1 plants screened) * 100. - Transgene-Free Rate:

(Number of edited T1 plants lacking transgene PCR amplicon / Total edited T1 plants) * 100.

- Inheritance Rate:

- Statistical Testing: Compare segregation ratios to expected Mendelian models (e.g., 3:1, 15:1) using Chi-square tests.

Visualizing Workflows and Relationships

Diagram 1: Core Metrics in the Base Editing Workflow

Diagram 2: Factors Influencing Core Editing Metrics

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item/Category | Function in Base Editing Experiments | Example/Supplier |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Accurate amplification of target loci for sequencing; prevents PCR-introduced errors. | Q5 (NEB), KAPA HiFi (Roche) |

| CTAB DNA Extraction Buffer | Robust isolation of high-quality genomic DNA from polysaccharide-rich plant tissues. | Standard molecular biology reagent. |

| Illumina Overhang Adapter Mix | Preparation of amplicon sequencing libraries for high-depth analysis of editing outcomes. | Nextera XT Index Kit (Illumina) |

| Agrobacterium Strain | Stable DNA delivery for many plant species via T-DNA integration. | GV3101 (for Arabidopsis), EHA105 (for monocots) |

| Purified Cas9 Protein (for RNP) | Enables transient, DNA-free delivery of base editors as Ribonucleoproteins, improving purity. | ToolGen, IDT, or in-house purification. |

| Deaminase-Specific Antibodies | Detection of base editor protein expression levels via Western blot, linking expression to efficiency. | Custom antibodies from vendors like GenScript. |

| Guide RNA in vitro Transcription Kit | Production of high-quality gRNA for RNP assembly or in planta transcription. | HiScribe T7 Kit (NEB) |

| Next-Generation Sequencing Service | Essential for unbiased quantification of editing frequency, purity, and off-target effects. | Novogene, Genewiz, or core facility. |

| Plant Tissue Culture Media | Selection and regeneration of transformed cells into whole plants. | MS Basal Medium with specific hormones. |

This whitepaper contextualizes foundational studies in model plants within the ongoing research thesis on determinants of base editing efficiency in plants. Insights from Arabidopsis thaliana, Oryza sativa (rice), and Solanum lycopersicum (tomato) provide the essential genetic, cellular, and transformative frameworks necessary to dissect factors influencing precision genome editing outcomes.

Quantitative Data from Foundational Base Editing Studies

Recent foundational studies have established key performance metrics for base editing across the three model species. The following tables summarize efficiency, specificity, and preferred system components.

Table 1: Base Editing Efficiency and Product Purity in Model Plants

| Plant Species | Target Gene | Editor System (Base Editor) | Average Editing Efficiency (%)* | Product Purity (Desired Base Change %) | Key Delivery Method | Reference (Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis | PDS3 | A3A-PBE (C-to-T) | 43.2 | 98.7 | Agrobacterium (Floral Dip) | Tang et al. (2022) |

| Arabidopsis | ALS | nCas9-UGI (C-to-T) | 19.8 | 99.1 | PEG-mediated Protoplast | Kang et al. (2023) |

| Rice | OsEPSPS | rAPOBEC1-nCas9 (C-to-T) | 61.5 | 96.3 | Agrobacterium (Callus) | Xu et al. (2023) |

| Rice | OsSBEIIb | ABE8e (A-to-G) | 38.7 | 94.8 | Particle Bombardment | Li et al. (2024) |

| Tomato | ALS1 | AID-nCas9 (C-to-T) | 12.4 | 97.9 | Agrobacterium (Cotyledon) | Yan et al. (2023) |

| Tomato | RIN | Target-AID (C-to-T) | 7.8 | 98.5 | Rhizogenes (Hypocotyl) | Tomlinson et al. (2022) |

Note: Efficiency calculated as percentage of independently transformed lines or cells with targeted edits.

Table 2: Factors Impacting Editing Efficiency & Specificity

| Factor | Impact on Efficiency | Impact on Specificity (Off-targets) | Species-Specific Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Promoter Driving Editor | Strong constitutive (e.g., 35S, ZmUbi) increases yield. | Can increase genome-wide off-targets. | Rice prefers ZmUbi; Tomato often uses 35S. |

| sgRNA Expression | Pol III promoters (U3, U6) are standard. Sequence/structure critical. | Mismatch tolerance influences off-target rate. | Arabidopsis U6-1, Rice U3, Tomato U6 show optimal activity. |

| Cellular State | Actively dividing cells (callus, meristem) show higher efficiency. | N/A | Critical for monocots (rice); less so for Arabidopsis dip. |

| Repair & Chromatin | Open chromatin (euchromatin) facilitates access. | N/A | Tomato showed lower efficiency in heterochromatic regions. |

| Editor Version | Newer deaminase variants (e.g., A3A, ABE8e) increase kinetics. | May alter window/stringency. | ABE8e in rice doubled A-to-G efficiency vs. ABE7.10. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Agrobacterium-Mediated Base Editor Delivery in Rice Callus (Adapted from Xu et al., 2023)

- Objective: Generate stable, heritable C-to-T edits in rice.

- Materials: Construct with ZmUbi promoter-driven rAPOBEC1-nCas9-UGI and rice U3 promoter-driven sgRNA; Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain EHA105; mature rice seed-derived embryogenic calli; N6-based co-cultivation media; selection media containing hygromycin.

- Procedure:

- Transform the base editor plasmid into Agrobacterium EHA105 via electroporation.

- Culture Agrobacterium in liquid medium with appropriate antibiotics to OD₆₀₀ ~1.0.

- Centrifuge and resuspend the bacterial pellet in co-cultivation medium supplemented with acetosyringone (200 µM).

- Immature rice calli (2-3 weeks post-subculture) are immersed in the Agrobacterium suspension for 20 minutes, blotted dry, and co-cultured on solid co-cultivation medium in the dark at 25°C for 3 days.

- Wash calli with sterile water containing cefotaxime (500 mg/L) to remove Agrobacterium.

- Transfer calli to selection media (hygromycin + cefotaxime) for 4-6 weeks, subculturing every 2 weeks.

- Regenerate plantlets from resistant calli on regeneration media.

- Extract genomic DNA from regenerated shoots (T0) and perform PCR/sequencing of the target locus to identify edits.

Protocol 2: PEG-Mediated Transfection of Arabidopsis Protoplasts for Rapid Efficiency Testing (Adapted from Kang et al., 2023)

- Objective: Rapid, transient quantification of base editing efficiency and product purity.

- Materials: Leaves from 3-4 week old Arabidopsis plants; enzyme solution (1.5% cellulase R10, 0.4% macerozyme R10, 0.4M mannitol, 20mM KCl, 20mM MES pH 5.7, 10mM CaCl₂, 0.1% BSA); PEG solution (40% PEG4000, 0.2M mannitol, 0.1M CaCl₂); base editor plasmid DNA (purified, endotoxin-free).

- Procedure:

- Slice leaves into 0.5-1mm strips and incubate in enzyme solution in the dark for 3-4 hours with gentle shaking.

- Filter the protoplast suspension through a 40µm nylon mesh, wash with W5 solution (154mM NaCl, 125mM CaCl₂, 5mM KCl, 2mM MES pH 5.7) by centrifugation at 100g for 2 minutes.

- Resuspend protoplast pellet in MMg solution (0.4M mannitol, 15mM MgCl₂, 4mM MES pH 5.7) at a density of 2x10⁵ cells/mL.

- For transfection, mix 10µg plasmid DNA with 100µL protoplast suspension. Add 110µL of PEG solution, mix gently, and incubate at room temperature for 15 minutes.

- Dilute the mixture gradually with 1mL of W5 solution, then centrifuge at 100g for 2 minutes.

- Resuspend the transfected protoplasts in 1mL of culture medium (0.4M mannitol, 4mM MES, 5mM KCl) and incubate in the dark at 22°C for 48-72 hours.

- Harvest protoplasts by centrifugation, extract genomic DNA, and analyze the target locus via high-throughput amplicon sequencing to calculate editing efficiency and product purity.

Mandatory Visualizations

Diagram Title: Base Editor Mechanism from Expression to DNA Change

Diagram Title: Base Editing Workflow in Plants

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Plant Base Editing Research

| Reagent / Material | Function & Rationale | Example Product / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Deaminase-Optimized Base Editor Plasmids | Pre-assembled vectors with plant-codon optimized editors (e.g., A3A-PBE, Target-AID, ABE8e) under plant promoters for ease of cloning. | pCAMBIA- or pRICE-based backbones with 35S/ZmUbi promoters. |

| Modular sgRNA Cloning Kits | Facilitates rapid, high-throughput assembly of sgRNA expression cassettes into plant vectors via Golden Gate or BsaI sites. | Plant Golden Gate MoClo Toolkit; U6/U3 entry vectors. |

| Agrobacterium Strains (Hypervirulent) | Essential for stable transformation of dicots (tomato, Arabidopsis) and monocots (rice). Hypervirulent strains increase T-DNA delivery. | EHA105, AGL1, LBA4404 (for tomato). |

| High-Fidelity PCR & Amplicon Sequencing Kits | Critical for accurate amplification and deep sequencing of target loci to quantify low-frequency edits and assess product purity. | KAPA HiFi Polymerase; Illumina-based amplicon-EZ service. |

| Protoplast Isolation Enzymes | For creating plant protoplasts for transient expression assays to rapidly test editor/sgRNA efficiency. | Cellulase R10, Macerozyme R10. |

| Plant Tissue Culture Media | Species-specific formulations for callus induction, co-cultivation, selection, and regeneration. Key for obtaining edited plants. | MS Basal Salts, N6 Medium, Gamborg's B5 Vitamins. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing Off-target Prediction Service | In silico prediction followed by whole-genome or targeted sequencing to assess editing specificity in generated plants. | Cas-OFFinder prediction; WGS or GUIDE-seq data analysis. |

Protocols in Practice: Strategies for High-Efficiency Plant Base Editing

Within the framework of optimizing base editing efficiency in plants, construct design is a critical determinant of success. The efficacy of a base editor (BE) is contingent not only on the editor's inherent activity but also on the delivery and expression levels of its components—typically a fusion of a Cas protein (nuclease-dead or nickase) and a deaminase. This technical guide focuses on two pivotal, tunable elements of the expression cassette: the promoter driving transgene expression and the codon optimization of the coding sequence. Strategic optimization of these factors is essential to achieve the high, sustained, and tissue-appropriate expression required for effective base editing outcomes in plant systems.

Promoter Selection: Driving Expression Strength and Specificity

The promoter controls the transcriptional initiation rate, spatial expression pattern, and temporal dynamics of the base editor. Selection hinges on the target organism, tissue, and desired editing window.

1.1 Key Promoter Classes for Plant Base Editing

- Constitutive Viral Promoters: Provide strong, ubiquitous expression.

- Cauliflower Mosaic Virus 35S (CaMV 35S): The historical standard for dicots. Its enhanced duplex version (d35S) offers higher strength.

- Figwort Mosaic Virus (FMV) Promoter: Often used as an alternative to 35S, with comparable strength in many dicots.

- Cassava Vein Mosaic Virus (CsVMV) Promoter: Exhibits strong activity in both monocot and dicot species.

- Constitutive Plant Promoters: Derived from housekeeping genes, they can offer reliable expression across kingdoms.

- Ubiquitin (Ubi) Promoters: From maize (Zea mays, Ubi1) or rice (Oryza sativa, OsAct1), these are the staples for strong, constitutive expression in monocots and are also functional in dicots.

- Actin (Act) Promoters: e.g., Rice Act1, commonly used in monocots.

- Inducible/Tissue-Specific Promoters: Useful for controlling editor expression temporally or limiting it to specific tissues (e.g., germline, meristems) to reduce somatic mosaicism and off-target effects.

- Heat-Shock Promoters (e.g., Hsp18, GmHSP17.5E): Allow rapid, transient induction of BE expression.

- Estrogen/Glucocorticoid-Inducible Systems: Chemically induced, offering precise temporal control.

- Germline-Specific (e.g., DD45), Meristem-Specific (e.g., RPS5a), or Vascular-Specific Promoters.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Common Constitutive Promoters in Plants

| Promoter Name | Origin | Preferred Host | Relative Strength (Arbitrary Units)* | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CaMV 35S | Cauliflower Mosaic Virus | Dicots (e.g., Arabidopsis, Tobacco) | 1.0 (Reference) | Strong, ubiquitous; enhanced duplex version available. |

| d35S | Enhanced 35S | Dicots | ~2-5x 35S | Upstream enhancer duplication increases strength. |

| FMV | Figwort Mosaic Virus | Dicots | ~0.8-1.2x 35S | Alternative to 35S, less prone to silencing in some species. |

| ZmUbi1 | Maize (Zea mays) | Monocots (e.g., Rice, Wheat) | Very High | Very strong, constitutive; includes intron for enhanced expression. |

| OsAct1 | Rice (Oryza sativa) | Monocots | High | Strong, constitutive; includes intron. |

| CsVMV | Cassava Vein Mosaic Virus | Both Mono- & Dicots | High in both | Broad-host range, strong activity. |

*Relative strength is species- and assay-dependent. Values are illustrative from historical GUS/Luciferase reporter studies.

1.2 Experimental Protocol: Comparative Promoter Strength Assay Objective: Quantify the transcriptional activity of candidate promoters driving a reporter gene in the target plant species. Materials: Binary vectors with promoter::reporter (e.g., GUS, Luciferase, GFP) constructs, Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain, plant materials.

- Construct Cloning: Clone each candidate promoter upstream of a promoter-less reporter gene (e.g., uidA for GUS) in a plant transformation vector.

- Plant Transformation: Transform the target plant species (e.g., via Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of leaf discs or stable Arabidopsis floral dip).

- Sample Collection: Harvest tissues (e.g., leaf, root, stem) from multiple independent T1 or T2 transgenic lines at a consistent developmental stage.

- Reporter Quantification:

- GUS: Perform fluorometric assay (4-MUG substrate) on total protein extracts. Measure fluorescence (Ex 365 nm, Em 455 nm).

- Luciferase: Assay lysates with luciferin substrate, measure luminescence with a plate reader.

- qRT-PCR: As a direct transcriptional readout, isolate RNA, synthesize cDNA, and perform qPCR using primers for the reporter gene. Normalize to housekeeping genes (e.g., EF1α, UBQ).

- Data Analysis: Compare mean activity levels across constructs, using lines transformed with a promoter-less reporter as negative control. Statistical analysis (ANOVA) is required.

Codon Optimization: Enhancing Translational Efficiency

Codon optimization involves modifying the coding sequence of a transgene (e.g., Cas9, deaminase) to match the codon usage bias of the host plant without altering the amino acid sequence. This maximizes translation efficiency and can significantly increase protein yield.

2.1 Key Principles

- Codon Adaptation Index (CAI): A measure of how similar the codon usage is to that of highly expressed host genes. A CAI of 1.0 is ideal.

- tRNA Abundance: Optimizing for codons corresponding to abundant tRNAs in the host prevents ribosomal stalling.

- GC Content: Adjusting to the host's typical genomic GC content can improve mRNA stability and transcription.

- Cryptic Splice Sites & Motifs: Removal of sequences that might trigger unintended RNA processing (e.g., polyadenylation signals, restriction sites).

Table 2: Impact of Codon Optimization on Base Editor Expression in Plants

| Base Editor Component | Original Host | Target Plant | Optimization Strategy | Outcome (Protein Level / Editing Efficiency)* | Reference Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 (nuclease) | S. pyogenes (Bacteria) | Arabidopsis thaliana | Plant-optimized codons, adjusted GC% | ~5-10x increase in detection / Up to 3x increase in mutation rate | Early CRISPR studies |

| rAPOBEC1 (deaminase) | H. sapiens (Mammal) | Oryza sativa (Rice) | Rice-preference codon optimization | Significant increase in BE protein accumulation / 2-4 fold increase in C•G to T•A conversion efficiency | BE3/ABE systems optimization |

| TadA (deaminase) | E. coli (Bacteria) | Zea mays (Maize) | Maize-codon optimization, CAI > 0.9 | Enhanced nuclear localization / Improved A•T to G•C conversion rates | ABE development in crops |

*Outcomes are comparative, showing the typical range of improvement over the non-optimized version.

2.2 Experimental Protocol: Assessing Codon Optimization Impact Objective: Compare the expression and functional efficiency of codon-optimized vs. native coding sequences for a BE component. Materials: Vectors containing native and plant-optimized versions of the gene (e.g., Cas9), antibodies for detection, functional editing assay.

- Construct Preparation: Generate two expression cassettes within identical vectors: one with the native CDS and one with the plant-optimized CDS, both under the same strong promoter (e.g., ZmUbi1).

- Transient Expression: Co-transform plant protoplasts with each BE construct and a GFP control plasmid (for normalization). Alternatively, use Agrobacterium-mediated transient infiltration (e.g., in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves).

- Western Blot Analysis (48-72h post-transfection):

- Extract total protein.

- Separate via SDS-PAGE, transfer to membrane.

- Probe with anti-Cas9 (or anti-deaminase) primary antibody and HRP-conjugated secondary antibody.

- Develop and quantify band intensity. Normalize to a loading control (e.g., Rubisco large subunit or co-expressed GFP).

- Functional In Vivo Assay: Co-deliver each BE construct with a target reporter plasmid containing a premature stop codon that can be corrected via base editing, restoring fluorescence (e.g., eGFP). Measure fluorescence recovery via flow cytometry or microscopy. Calculate the editing efficiency as % of cells fluorescing.

- Data Correlation: Correlate the relative protein abundance (Western) with the functional editing efficiency (reporter assay).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Promoter & Codon Optimization Studies

| Item | Function & Rationale | Example/Source |

|---|---|---|

| Modular Plant Binary Vectors | Gateway- or Golden Gate-compatible backbones for rapid, standardized assembly of promoter::gene::terminator cassettes. | pGREEN, pCAMBIA, pHUE vectors; MoClo Plant Toolkit parts. |

| Codon Optimization Software | In silico tools to redesign gene sequences for optimal expression in the target plant host. | IDT Codon Optimization Tool, GeneArt (Thermo), Twist Bioscience Codon. |

| qRT-PCR Master Mix | For sensitive, quantitative measurement of transcript levels from different promoters. | SYBR Green or TaqMan-based mixes (e.g., from Bio-Rad, Thermo). |

| Fluorometric GUS Assay Kit | Quantitative measurement of β-glucuronidase activity as a proxy for promoter strength. | 4-MUG based kits (e.g., from Sigma-Aldrich). |

| Anti-Cas9 / Anti-Deaminase Antibodies | Essential for Western blot to quantify protein accumulation from different CDS versions. | Commercial antibodies (e.g., anti-Cas9 from Abcam, Diagenode). |

| Plant Protoplast Isolation & Transfection Kit | Enables rapid, high-throughput transient expression testing of constructs. | Isolation enzymes (Cellulase, Macerozyme), PEG transfection reagents. |

| Reporter Plasmids for Editing | Plasmids containing a disruptable fluorescent protein gene to quantify base editing efficiency in vivo. | e.g., pBSEditor-GFP (contains a targetable premature stop codon). |

Within the critical research on base editing efficiency factors in plants, the choice of delivery method is a primary determinant of success. The method directly influences the rate of transgene integration, the complexity of the delivered construct, the precision of editing, and the subsequent regeneration of edited plants. This guide provides an in-depth technical comparison of the three principal delivery modalities—Agrobacterium-mediated transformation, biolistics, and protoplast transformation—focusing on their impact on base editing outcomes.

Core Mechanisms and Comparative Analysis

Agrobacterium-Mediated Transformation

This biological method utilizes the natural gene-transfer capability of the soil bacterium Agrobacterium tumefaciens. The bacterium transfers a specific segment (T-DNA) of its tumor-inducing (Ti) plasmid into the plant cell nucleus, where it integrates into the host genome.

Key Protocol:

- Vector Preparation: The gene of interest (e.g., a base editor expression cassette) is cloned into a binary vector between the T-DNA borders.

- Bacterial Transformation: The recombinant vector is introduced into a disarmed Agrobacterium strain (e.g., LBA4404, GV3101).

- Plant Material Preparation: Target explants (e.g., leaf discs, cotyledons, embryogenic calli) are pre-cultured.

- Co-cultivation: Explants are immersed in the Agrobacterium suspension (OD~600nm=0.5-1.0) for 5-30 minutes, then co-cultured on solid medium for 2-3 days to allow T-DNA transfer.

- Washing & Selection: Explants are washed with sterile water containing antibiotics (e.g., cefotaxime) to eliminate Agrobacterium and transferred to selection medium containing both antibiotics and a plant-selectable agent (e.g., hygromycin).

- Regeneration: Developing shoots are transferred to rooting medium to regenerate whole plants.

Biolistics (Particle Bombardment)

A physical method where microscopic gold or tungsten particles coated with DNA are accelerated into plant cells using a gene gun. The DNA may integrate into the nuclear or organellar genome.

Key Protocol:

- Microcarrier Preparation: Tungsten or gold particles (0.6-1.0 µm) are coated with purified plasmid DNA expressing the base editor components, using CaCl₂ and spermidine as precipitating agents.

- Target Tissue Preparation: Embryogenic calli or immature embryos are placed on osmoticum treatment medium (e.g., high sucrose or mannitol) to plasmolyze cells, reducing cytoplasmic leakage.

- Bombardment: Tissues are bombarded under a partial vacuum using a helium-driven gene gun (e.g., Bio-Rad PDS-1000/He). Parameters (helium pressure, target distance, particle load) are optimized per tissue type.

- Post-bombardment Recovery: Tissues are kept on osmoticum medium for 12-24 hours, then transferred to standard culture medium.

- Selection & Regeneration: Following a recovery period (5-7 days), tissues are moved to selection medium for transgenic event recovery and subsequent plant regeneration.

Protoplast Transformation (PEG or Electroporation)

This method involves the isolation of plant cells devoid of cell walls (protoplasts), followed by direct delivery of DNA or ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes via chemical (PEG) or electrical (electroporation) means. It is ideal for transient assays and can facilitate base editing without stable DNA integration.

Key Protocol:

- Protoplast Isolation: Leaf mesophyll tissue or cultured cells are digested in an enzyme solution (e.g., Cellulase R10, Macerozyme R10, Mannitol) for 4-16 hours.

- Protoplast Purification: The digestate is filtered, and protoplasts are pelleted via centrifugation through a sucrose or Percoll cushion. Washing is performed in W5 or MaMg solution.

- Transformation:

- PEG-Mediated: Protoplasts are incubated with DNA/RNP in a PEG-Ca²⁺ solution (e.g., 40% PEG4000) for 15-30 minutes.

- Electroporation: Protoplasts are mixed with DNA/RNP and subjected to a high-voltage pulse (e.g., 300-500 V/cm, 10-50 ms) in an electroporation cuvette.

- Culture & Analysis: Protoplasts are washed, cultured in a low-light environment, and harvested after 24-72 hours for rapid molecular analysis of editing efficiency. Regeneration into whole plants is possible but remains genotype-dependent and challenging.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Delivery Method Parameters for Base Editing

| Parameter | Agrobacterium-Mediated | Biolistics | Protoplast Transformation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Delivery Format | Plasmid DNA (T-DNA) | Plasmid DNA, linear fragments, or RNPs | Plasmid DNA, linear fragments, or RNPs |

| Max. Cargo Size | Very Large (>50 kb) | Very Large (No practical limit) | Moderate (Limited by transfection efficiency) |

| Typical Transformation Efficiency | Medium-High (Varies by species, 1-80% stable) | Low-Medium (0.1-10 stable events/shot) | Very High (Transient, up to 80%+), Low (Stable, genotype-dependent) |

| Copy Number Integration | Mostly Low-Copy (1-3), precise | Often Multi-Copy, complex insertions | Can be Transient (No integration) or low-copy |

| Genotype Dependence | High | Lower (works on recalcitrant species) | Very High (requires robust protoplast culture/regeneration) |

| Throughput Potential | Medium | High (for large-scale screening) | Very High (for rapid transient assays) |

| Regeneration Timeline | Long (Months) | Long (Months) | Short for assay (Days), Long/Challenging for plants |

| Chimeric Edits Risk | Medium | High (multiple cell targets) | Low (single cell origin) |

| Primary Use Case | Stable line generation, large constructs | Species recalcitrant to Agrobacterium, organelle transformation | Rapid efficiency optimization, in planta function testing |

Table 2: Reported Base Editing Efficiencies Across Delivery Methods (Model Plants)

| Plant Species | Delivery Method | Base Editor Type | Target Locus | Efficiency (Range) | Key Factor Impacting Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice (Oryza sativa) | Agrobacterium | APOBEC1-nCas9-UGI | OsPDS, OsSBEIIb | 10% - 50% (Stable lines) | T-DNA design, promoter selection, tissue culture response |

| Rice | Protoplast (PEG) | BE3, ABE | OsNRT1.1B | Up to 75% (Transient) | Protoplast viability, RNP:DNA ratio, PEG concentration |

| Wheat (Triticum aestivum) | Biolistics | AID-nCas9-UGI | TaLOX2, TaALS | 1% - 10% (Stable) | Particle penetration depth, promoter strength, selection |

| Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) | Agrobacterium | evoFERNY-nCas9-UGI | Solyc08g075770 | 20% - 70% (Stable) | Co-cultivation time, Agrobacterium strain, suppressor genes (e.g., VirE1) |

| Maize (Zea mays) | Biolistics | ABE8e | ZmALS1, ZmALS2 | Up to 9.6% (Stable) | Donor DNA form, tissue health, bombardment parameters |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | Agrobacterium (Floral Dip) | nCas9-UGI-AtAPOBEC1 | Various | 0.1% - 6% (Next gen) | Plant developmental stage, surfactant concentration |

Visualized Workflows and Relationships

Diagram Title: Delivery Method Decision Logic for Plant Base Editing

Diagram Title: Agrobacterium-Mediated Transformation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Delivery Method Experiments

| Item | Function | Example(s)/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Binary Vectors | Carries T-DNA with base editor cassette for Agrobacterium transformation. | pCAMBIA, pGreenII, pMDC series; Must contain left/right borders, plant selection marker, bacterial origin. |

| Agrobacterium Strains | Disarmed, helper plasmid-containing strains for efficient plant transformation. | LBA4404 (octopine), EHA105/101 (super-virulent), GV3101 (for Arabidopsis floral dip). |

| Gold Microcarriers | Inert, high-density particles for coating DNA in biolistics. | 0.6 µm or 1.0 µm gold microparticles (Bio-Rad); preferred over tungsten for consistency. |

| Gene Gun/ Biolistic Device | Instrument to accelerate DNA-coated particles into tissue. | PDS-1000/He System (Bio-Rad) or handheld devices for in planta use. |

| Cell Wall Digesting Enzymes | Degrade cellulose/pectin to isolate protoplasts. | Cellulase R10, Macerozyme R10 (Yakult); concentration optimized per species. |

| PEG Solution | Induces membrane fusion and DNA uptake in protoplasts. | PEG 4000 (40% w/v) in MaMg or Ca(NO₃)₂ solution; must be freshly prepared or aliquoted. |

| Electroporator | Applies controlled electrical pulse to permeabilize protoplast membranes. | Square-wave electroporators (e.g., Bio-Rad Gene Pulser Xcell) for high efficiency RNP delivery. |

| Osmoticum/ Washing Solutions | Maintain protoplast integrity and wash post-transformation. | W5 solution (154 mM NaCl, 125 mM CaCl₂, etc.), Mannitol (0.4-0.6 M) for enzyme digestion. |

| Plant Tissue Culture Media | Supports growth, selection, and regeneration of transformed tissues. | MS (Murashige & Skoog), N6, B5 media, supplemented with appropriate hormones (2,4-D, BAP, NAA). |

| Selection Agents | Eliminates non-transformed tissue post-delivery. | Antibiotics: Hygromycin, Kanamycin. Herbicides: Phosphinothricin (PPT/BASTA), Chlorsulfuron. |

| Vir Gene Inducers | Enhances Agrobacterium virulence for difficult species. | Acetosyringone (100-200 µM), added to co-cultivation media. |

Within the broader thesis investigating base editing efficiency factors in plants, target site selection emerges as the foundational determinant of success. While factors like editor expression, delivery, and cellular repair pathways are critical, the intrinsic genomic context of the target locus—primarily defined by the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) requirement and the surrounding sequence—imposes the first and most stringent constraint. This guide provides a technical analysis of how PAM specificity and local sequence features govern the feasibility, precision, and efficacy of base editing in plant genomes, directly influencing experimental design and outcome predictability.

PAM Specificity: The Gateway to DNA Recognition

CRISPR-Cas-derived base editors do not create double-strand breaks but retain the PAM-dependent targeting of their parent Cas nuclease. The PAM is a short, non-editable sequence adjacent to the target protospacer that is essential for Cas protein recognition and binding.

Table 1: Common Cas Proteins and Their PAM Requirements for Plant Base Editing

| Cas Protein | Base Editor Variant | Canonical PAM Sequence | Implications for Plant Target Selection |

|---|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 | BE3, BE4, ABE7.10 | 5'-NGG-3' (3' of target) | Broadest applicability; high frequency of NGG sites in plant genomes. |

| SpCas9-NG | NG-BE, NG-ABE | 5'-NG-3' (3' of target) | Doubles targeting range; useful for AT-rich genomic regions. |

| xCas9 (SpCas9 variant) | xBE, xABE | 5'-NG, GAA, GAT-3' (3') | Relaxed PAM, but may exhibit reduced activity in plants. |

| SaCas9 | SaBE, SaABE | 5'-NNGRRT-3' (3' of target) | Smaller size advantageous for viral delivery; fewer target sites. |

| Cas12a (Cpfl) | A3A-Cpfl-BE | 5'-TTTV-3' (5' of target) | Enables editing in T-rich regions; creates staggered cuts (consider for dual editing). |

Diagram Title: PAM-Dependent Cas Protein Binding and Editing Window Activation (Max 760px)

Sequence Context Determinants of Editing Efficiency

Beyond the PAM, local sequence features critically modulate base editing outcomes. For Cytosine Base Editors (CBEs) and Adenine Base Editors (ABEs), efficiency is not uniform across the editable window.

Table 2: Impact of Sequence Context on Base Editing Efficiency

| Factor | Impact on CBE (C-to-T) | Impact on ABE (A-to-G) | Experimental Evidence in Plants |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Nucleotide Position | Highest efficiency at positions C5-C8 (SpCas9). | Highest efficiency at positions A4-A7 (SpCas9). | Rice protoplast assays show steep drop-off outside optimal window. |

| Sequence Motif Preference | TC contexts edited more efficiently than AC, GC, or CC. | Generally less motif-sensitive than CBEs. | In Arabidopsis, TC motifs showed >80% editing vs. ~40% for GC. |

| Local GC Content | High GC (>60%) can impede efficiency. | Moderate effect; high AT may favor editing. | Maize callus lines showed reduced CBE efficiency in high-GC regions. |

| Secondary Structures | R-loops or hairpins at target site can inhibit access. | Similar inhibitory effect as for CBEs. | Predicted in silico and correlated with low efficiency in tomato. |

| Epigenetic Marks | Dense DNA methylation (e.g., CG, CHG) can reduce efficiency. | Effect less pronounced but possible. | Hypomethylated rice mutants showed increased CBE efficiency at some loci. |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Target Site Viability

Protocol 1: In Silico Target Site Selection and Ranking

- Sequence Extraction: Retrieve 200-300 bp genomic sequence surrounding the gene of interest from a reference genome database (e.g., Phytozome).

- PAM Scanning: Use software (e.g., CRISPR-P 2.0, Cas-Designer) to identify all instances of the required PAM (e.g., NGG for SpCas9).

- Protospacer Definition: Extract the 20-nt sequence immediately 5' to each PAM.

- Off-Target Prediction: Submit each 20-nt spacer sequence to plant-specific off-target prediction tools (e.g., CRISPR-PLANT, CCTop) with appropriate genome parameters.

- Efficiency Scoring: Rank targets using predictive scores (e.g., Doench ‘16 score adapted for plants, or SpCas9-specific prediction models). Prioritize targets where the desired base change falls within positions 4-10 of the protospacer.

- Contextual Analysis: Annotate top candidates for local GC content, sequence motifs, and potential for DNA secondary structure (analyze via UNAFold/mfold).

Protocol 2: In Planta Validation via Protoplast Transfection

- Construct Assembly: Clone validated spacer sequences into appropriate base editor expression vectors (e.g., pZmUbi-BE4 or pAtU6-sgRNA/AtUBQ-ABE).

- Plant Material: Isolate mesophyll protoplasts from sterile plant seedlings (e.g., Arabidopsis, rice) using cellulase/macerozyme digestion.

- Co-transfection: Transfect 10-20 µg of base editor plasmid DNA into 0.5-1 million protoplasts using PEG-mediated transformation.

- Incubation: Incubate protoplasts in the dark at 22-25°C for 48-72 hours.

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Harvest protoplasts, extract gDNA using a CTAB or silica-column method.

- PCR and Sequencing: Amplify the target locus from transfected and control samples. Perform Sanger sequencing and analyze editing efficiency using chromatogram decomposition tools (e.g., BEAT, EditR) or deep sequencing (amplicon-seq).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item/Reagent | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Plant-Optimized Base Editor Vectors (e.g., pYB series, pCAMBIA-BE) | Contain plant promoters (Ubi, Yao, AtU6) and terminators for high-level, stable expression in monocots/dicots. |

| Gibson Assembly or Golden Gate Mixes (e.g., BsaI-HFv2, Esp3I) | For modular, high-efficiency cloning of sgRNA expression cassettes into editor backbones. |

| Plant Codon-Optimized Cas9 Variants (e.g., SpCas9-NG) | Ensures robust expression and nuclear localization in plant cells, critical for PAM recognition. |

| Agrobacterium Strain GV3101 (pSoup) | Standard for stable plant transformation (e.g., floral dip, callus infection) of base editing constructs. |

| Protoplast Isolation Enzymes (Cellulase R10, Macerozyme R10) | High-purity enzymes for generating viable plant protoplasts for rapid transient assays. |

| PEG-Calcium Transfection Solution (40% PEG4000) | Induces DNA uptake into protoplasts for efficient, transient editor delivery and rapid testing. |

| High-Fidelity PCR Kits (e.g., Phusion, KAPA HiFi) | Essential for error-free amplification of target loci from complex plant genomes for sequencing analysis. |

| Amplicon-Seq Library Prep Kits (e.g., Nextera XT) | Enables high-throughput, quantitative assessment of editing efficiency and byproduct profiling. |

Integrated Workflow for Target Selection and Validation

Diagram Title: Integrated Workflow for Target Selection and Validation (Max 760px)

The precision of base editing in plants is irrevocably constrained at the point of target selection by the interplay of PAM availability and sequence context. A rigorous, multi-step validation pipeline—from in silico prediction to transient protoplast assays—is non-negotiable for de-risking subsequent stable plant transformation efforts. For research framing a thesis on base editing efficiency, these factors represent the primary independent variables. Mastery of PAM constraints and contextual nuances directly enables the rational design of editing strategies, the accurate interpretation of heterogeneous editing outcomes, and the systematic improvement of editing tools tailored for plant genomes.

This guide details practical applications of base editing in plant systems, framed within the critical research thesis: "Base editing efficiency in plants is a multivariate function of guide RNA design, editor expression dynamics, cellular delivery efficacy, and tissue-specific repair outcomes." The showcased applications for disease resistance and metabolic engineering must be evaluated against these core efficiency factors to enable robust, predictable genome engineering.

Key Quantitative Data on Plant Base Editing Systems

Recent advancements have yielded diverse base editing platforms with varying efficiencies and product purity. The following table summarizes key performance metrics from recent studies (2023-2024).

Table 1: Comparison of Recent Base Editor Systems in Plants (2023-2024)

| Editor System & Target Plant | Target Gene / Trait | Avg. Editing Efficiency (%)* | Product Purity (Desired:Undesired) | Key Delivery Method | Primary Citation (Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/ABE8e (Tomato) | SLPWRKY (Disease Res.) | 67.3% (T2 lines) | 89.2 : 10.8 (A•T to G•C) | Agrobacterium (T-DNA) | Li et al., Nature Plants (2023) |

| CRISPR/CBE-V01 (Rice) | OsALS (Herbicide Res.) | 58.1% (T0 plants) | 94.5 : 5.5 (C•G to T•A) | RNP Delivery (PEG) | Cheng et al., PBJ (2024) |

| enCas12a-BE (Wheat) | TaMLO (Powdery Mildew) | 41.5% (T0 calli) | 98.1 : 1.9 (C•G to T•A) | Particle Bombardment | Wang et al., Science Adv. (2023) |

| TadA-8e dCpf1-BE (Potato) | SSIV (Starch Metabolism) | 23.7% (T0 plants) | 82.4 : 17.6 (A•T to G•C) | Agrobacterium (T-DNA) | Veley et al., Plant Cell (2024) |

| Dual APOBEC-CBE (Maize) | ZmALS1 & ZmALS2 | 71.2% (ALS1) / 36.4% (ALS2) | 96.3 : 3.7 (C•G to T•A) | Agrobacterium + Morphogenic Regulators | Liang et al., Cell Rep. (2023) |

Efficiency measured as percentage of sequenced alleles containing the desired point mutation in primary transformants (T0) or progeny (T2). *Product Purity = Ratio of intended base conversion to indels or other unintended edits (e.g., bystander edits).

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: Creating Disease Resistance viaMLOGene Knockout in Wheat using enCas12a-BE

This protocol demonstrates the interplay of editor expression and delivery on efficiency.

1. gRNA Design and Vector Construction:

- Design a 20-nt spacer sequence targeting the conserved exon region of the TaMLO-B1 allele (e.g., 5'-GAGTGTCGTGATGGCAACAC-3') within an NGG PAM for SpCas9-derived BE or TTTV PAM for Cas12a-BE.

- Clone the spacer into a plant-optimized base editor expression vector (e.g., pEnCas12a-APOBEC1-NG) using Golden Gate assembly. The vector includes a Pol II-driven editor and Pol III-driven gRNA.

2. Plant Material and Delivery:

- Use immature embryos of wheat (Triticum aestivum) cultivar 'Fielder'.

- Deliver plasmid DNA via particle bombardment (Biolistic PDS-1000/He). Parameters: 650 psi rupture disk, 6 cm target distance, 0.6 µm gold microparticles coated with 2 µg vector DNA per shot.

3. Tissue Culture and Regeneration:

- Place bombarded embryos on callus induction medium (CIM) containing 2,4-D for 2 weeks.

- Transfer proliferating calli to regeneration medium (RM) without auxin to promote shoot formation over 4-6 weeks.

- Transfer developed shoots to root induction medium.

4. Screening and Genotyping:

- Extract genomic DNA from leaf tissue of regenerated plantlets (T0).

- Perform PCR amplification of the TaMLO-B1 target region.

- Use Sanger sequencing followed by chromatogram decomposition analysis (e.g., using BEAT or EditR software) or high-throughput amplicon sequencing to quantify C-to-T conversion efficiency and indel frequency.

Protocol B: Metabolic Engineering for Starch Composition in Potato using TadA-8e dCpf1-BE

This protocol highlights the factor of tissue-specific expression and repair.

1. Target and Construct Design for Metabolic Pathway:

- Target the Granule-Bound Starch Synthase (GBSS) gene to create a premature stop codon (Tryptophan TGG → Stop TAG via C-to-T edit) for waxy potato starch.

- Use a Tissue-Specific Promoter (e.g., tuber-specific Patatin promoter) to drive expression of the TadA-8e dCpf1-ABE fusion protein. A separate U6 promoter drives the crRNA.

2. Delivery and Plant Generation:

- Transform potato (Solanum tuberosum) internode explants using Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 harboring the binary vector.

- Co-cultivate for 48 hours, then transfer to selection medium containing kanamycin and cefotaxime.

- Regenerate whole plants via organogenesis over 12-16 weeks.

3. Phenotypic and Metabolic Analysis:

- Screen tubers from greenhouse-grown plants (T1 generation) for iodine staining (waxy starch stains reddish-brown).

- Quantify amylose content using a iodometric assay or size-exclusion chromatography.

- Confirm genotype by sequencing the target locus from tuber and leaf tissue separately to assess tissue-specific editing efficiency.

Visualization Diagrams

Core Base Editing Workflow in Plants

Key DNA Repair Pathways Influencing Base Editing Outcomes

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Plant Base Editing Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function & Rationale | Example Product / Source |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Assembly Kit | For error-free cloning of gRNA spacers and editor cassettes into often large, repetitive plasmid backbones. | NEB Gibson Assembly, Golden Gate Toolkits (e.g., MoClo Plant Parts). |

| Plant-Codon Optimized Base Editor Plasmids | Pre-constructed vectors with editor (e.g., rAPOBEC1, TadA-8e) and nuclease (dCas9, dCas12a) fused, driven by plant-specific promoters (e.g., 2x35S, ZmUbi). | Addgene repositories (e.g., pYPQ series, pCBE- plant vectors). |

| Chemically Modified sgRNA or crRNA | For RNP delivery; chemical modifications (2'-O-methyl, phosphorothioate) enhance stability in plant cells. | Synthesized from commercial oligo providers (IDT, Sigma). |

| Agrobacterium Strain (GV3101, EHA105) | Standard for T-DNA delivery in dicots and some monocots. Competent cells optimized for binary vector transformation. | Various commercial competent cell preparations. |

| Plant Tissue Culture Media Bases | Pre-mixed salts and vitamins for preparing callus induction, regeneration, and selection media (MS, N6, B5 formulations). | PhytoTech Labs, Duchefa Biochemie. |

| Selection Agents (Antibiotics/Herbicides) | For selecting transformed tissue post-delivery (e.g., Kanamycin, Hygromycin B, Glufosinate). | Standard laboratory suppliers. |

| High-Fidelity Polymerase for Amplicon Seq | Critical for unbiased PCR amplification of target loci prior to sequencing to assess editing efficiency. | KAPA HiFi, Q5 Hot-Start (NEB). |

| NGS-based Amplicon Sequencing Service/Kits | For deep, quantitative analysis of editing outcomes, bystander edits, and indel frequencies. | Illumina MiSeq with custom amplicon panels, EasySeq from Novogene. |

| Genotype-Phenotype Linking Software | Tools to deconvolute Sanger sequencing chromatograms or analyze NGS amplicon data for base edits. | BEAT, EditR, CRISPResso2. |

Within the research thesis on base editing efficiency factors in plants, the accurate screening and selection of edited events is paramount. This technical guide details the core PCR-based and NGS methodologies employed to identify, quantify, and characterize edits, enabling the dissection of factors influencing editor performance, delivery, and repair outcomes in plant systems.

PCR-Based Screening Assays

PCR assays provide rapid, cost-effective initial screening for putative edit events prior to deep sequencing.

Key Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 1: Comparison of PCR-Based Screening Assays

| Assay Type | Primary Detection | Sensitivity (Variant AF) | Throughput | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (RFLP) | Loss of restriction site | ~5-10% | Medium | Limited to edits that alter enzyme recognition sites |

| Amplicon Sequencing (Sanger) | Sequence chromatogram | ~15-20% | Low | Low sensitivity for mosaic edits |

| High-Resolution Melting (HRM) | Melting curve shift | ~5-10% | High | Requires optimization; indirect sequence data |

| Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) | Absolute quantification | ~0.1-1% | Medium | Requires specific probe/assay design per target |

| T7 Endonuclease I / CEL-I Assay | Mismatch cleavage | ~1-5% | Medium | High false-positive rate; indirect |

Detailed Protocol: ddPCR for Base Edit Quantification

This protocol quantifies the percentage of edited alleles in a bulk plant tissue sample post-transformation.

Materials:

- Genomic DNA (20-50 ng/µL) from pooled plant tissue.

- ddPCR Supermix for Probes (No dUTP).

- FAM-labeled probe: Targets the edited sequence.

- HEX/VIC-labeled probe: Targets the wild-type sequence.

- Primers: Flanking the target site (amplicon 80-150 bp).

- Droplet Generator and Droplet Reader.

Methodology:

- Prepare Reaction Mix: For one sample, combine 10 µL of 2x ddPCR Supermix, 1 µL of 20x primer/probe mix (final: 900 nM primers, 250 nM each probe), 5 µL of gDNA (100 ng), and nuclease-free water to 20 µL.

- Generate Droplets: Transfer 20 µL of the mix to a DG8 cartridge. Pipette 70 µL of Droplet Generation Oil into the oil well. Generate droplets using the QX200 Droplet Generator.

- PCR Amplification: Transfer 40 µL of emulsified droplets to a 96-well PCR plate. Seal and run on a thermal cycler: 95°C for 10 min; 40 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec and 58-60°C (assay-specific) for 60 sec; 98°C for 10 min (ramp rate: 2°C/sec).

- Read Droplets: Load plate into the QX200 Droplet Reader. The software counts the number of FAM-positive (edited), HEX-positive (wild-type), and double-positive droplets.

- Calculate Editing Efficiency: Editing Efficiency (%) = [FAM-positive droplets / (FAM-positive + HEX-positive + double-positive droplets)] * 100. This gives the variant allele frequency (VAF) in the bulk sample.

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Workflows

NGS provides comprehensive, quantitative characterization of editing outcomes, including precise base changes, indel byproducts, and mosaicism.

Amplicon Sequencing Workflow

Table 2: Key Steps in Amplicon-Seq for Base Editing Analysis

| Step | Description | Critical Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Primer Design | Design primers 50-100bp from target site. | Add Illumina adapter overhangs; ensure no primer-dimer; check specificity. |

| 2. PCR Amplification | 1st PCR: Target-specific amplification. | Use high-fidelity polymerase; limit cycles (≤25) to reduce recombination. |

| 3. Indexing PCR | 2nd PCR: Add dual indices and sequencing adapters. | Purify 1st PCR product; limit cycles (≤10). |

| 4. Library QC & Pooling | Quantify libraries (e.g., Qubit), check size (Bioanalyzer). | Normalize concentrations before equimolar pooling. |

| 5. Sequencing | Run on MiSeq, NextSeq (2x150bp or 2x250bp). | Aim for >10,000x depth per amplicon for sensitive detection. |

| 6. Data Analysis | Demultiplex, align to reference, call variants. | Use tools like CRISPResso2, BaseEditR, or custom pipelines. |

Detailed Protocol: Two-Step PCR Amplicon Library Preparation

Materials:

- High-fidelity DNA Polymerase (e.g., Q5 Hot Start).

- Gel Extraction or Bead-based Cleanup Kit.

- Indexing primers (i5 and i7).

- SPRIselect beads.

Methodology:

- Primary PCR: Amplify target locus from 50-100ng gDNA in a 50µL reaction: initial denaturation 98°C, 30s; 25 cycles of (98°C, 10s; 60-65°C, 20s; 72°C, 20s); final extension 72°C, 2min.

- Purify Amplicons: Clean up PCR product using SPRIselect beads (0.8x ratio). Elute in 25 µL TE buffer.

- Indexing PCR: Use 2-5 µL of purified primary PCR as template in a 25µL reaction with indexing primers. Run for 8 cycles using the same thermocycling profile.

- Final Library Purification: Pool indexing reactions if multiple samples. Clean with SPRIselect beads (0.8x ratio). Quantify and size-select via capillary electrophoresis.

- Sequencing & Analysis: Dilute, denature, and load per sequencer protocol. Align FASTQ files to reference genome using BWA-MEM. Analyze with CRISPResso2 (

CRISPResso2 -r1 sample.fastq.gz -a amplicon_sequence.txt -g guide_RNA_seq).

Visualizing Workflows and Logical Relationships

Screening and Selection Workflow for Base Editing

Amplicon-Seq Bioinformatics Analysis Pipeline

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Screening & Selection

| Item | Function & Application | Example Product/Kit |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Minimizes PCR errors during amplicon generation for NGS. Critical for accurate variant calling. | Q5 Hot Start (NEB), KAPA HiFi HotStart |

| ddPCR Supermix for Probes | Enables absolute quantification of edit allele frequency without standard curves. | Bio-Rad ddPCR Supermix for Probes (No dUTP) |

| SPRIselect Beads | Size selection and purification of DNA fragments (amplicons, libraries). Enables reproducible cleanups. | Beckman Coulter SPRIselect |

| T7 Endonuclease I | Detects mismatches in heteroduplex DNA for initial identification of editing activity. | NEB T7 Endonuclease I |

| Illumina Indexing Primers | Adds unique dual indices to amplicons for multiplexed sequencing of pooled samples. | Illumina Nextera XT Index Kit v2 |

| Library Quantification Kit | Accurate quantification of sequencing library concentration for optimal pooling and loading. | KAPA Library Quantification Kit (Illumina) |