Multi-Omics Data Integration in Plant Research: Pipelines, Applications, and Future Directions

This article provides a comprehensive overview of multi-omics data integration strategies for plant research, addressing the needs of researchers and scientists.

Multi-Omics Data Integration in Plant Research: Pipelines, Applications, and Future Directions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of multi-omics data integration strategies for plant research, addressing the needs of researchers and scientists. It explores the foundational principles of integrating genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics to understand complex plant systems. The content details practical methodological approaches, from data fusion to advanced computational tools, and addresses key challenges in data heterogeneity and analysis. Through validation case studies and comparative performance analysis, it demonstrates how integrated multi-omics pipelines enhance predictive accuracy for traits like stress response and yield, offering actionable insights for crop improvement and biomedical applications.

The Multi-Omics Landscape in Plant Systems Biology

Modern plant research leverages a suite of high-throughput technologies, collectively known as "omics," to comprehensively study biological systems. These technologies enable the systematic characterization and quantification of pools of biological molecules that define the structure, function, and dynamics of plants. The core omics disciplines—genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—provide complementary insights into the molecular mechanisms governing plant growth, development, and responses to environmental stimuli.

When integrated through multi-omics approaches, these technologies provide unprecedented insights into the molecular basis of key agronomic traits such as crop resilience and productivity [1]. For instance, in rice, integrated genomics and metabolomics have identified key loci and metabolic pathways controlling grain yield and nutritional quality, while in maize, transcriptomic and genomic analyses have identified networks regulating flowering time and drought tolerance [1]. These studies underscore the potential of multi-omics in linking molecular variation with complex agronomic traits, providing a foundation for advanced crop improvement strategies for sustainable agriculture.

Core Omics Technologies: Principles and Applications

Genomics

Genomics involves the comprehensive study of an organism's complete set of DNA, including genes, non-coding regions, and structural elements. It provides the foundational blueprint that encodes the potential characteristics and functions of a plant.

- Primary Focus: Sequencing, assembly, and annotation of entire genomes; identification of genetic variants such as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and structural variations.

- Key Technologies: Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) for whole-genome sequencing, genotyping-by-sequencing, and genome-wide association studies (GWAS).

- Plant Research Applications: Uncovering genetic determinants of yield, disease resistance, and abiotic stress tolerance; guiding marker-assisted selection and genomic prediction in breeding programs [2].

Transcriptomics

Transcriptomics is the study of the complete set of RNA transcripts, including messenger RNA (mRNA), non-coding RNA, and other RNA species, produced by the genome under specific conditions or in a specific cell type.

- Primary Focus: Quantifying the expression levels of genes to understand regulatory dynamics and functional responses.

- Key Technologies: RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), microarrays, and single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq).

- Plant Research Applications: Profiling gene expression changes during stress responses, identifying key regulatory genes, and understanding spatiotemporal development [3] [4]. Single-cell transcriptomics further allows the dissection of cellular heterogeneity within complex plant tissues.

Proteomics

Proteomics entails the large-scale study of the entire complement of proteins, including their structures, functions, modifications, and interactions. Proteins are the primary functional actors within the cell.

- Primary Focus: Identifying and quantifying protein abundance, post-translational modifications (PTMs), and protein-protein interactions.

- Key Technologies: Mass spectrometry (MS)-based techniques, often coupled with separation methods like liquid chromatography (LC-MS/MS) or two-dimensional gel electrophoresis.

- Plant Research Applications: Elucidating signaling networks, understanding post-translational regulation in stress responses, and characterizing metabolic enzymes and their activities.

Metabolomics

Metabolomics focuses on the comprehensive analysis of all small-molecule metabolites (typically <2000 Da) within a biological system. Metabolites represent the ultimate downstream product of genomic expression and provide a direct readout of cellular physiological status.

- Primary Focus: Identifying and quantifying the complete set of metabolites in a biological sample to understand the metabolic phenotype.

- Key Technologies: Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS), liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS), nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), and mass spectrometry imaging for spatial resolution [5].

- Plant Research Applications: Discovering compounds involved in stress adaptation, assessing nutritional quality, and uncovering metabolic pathways for biofortification or drug discovery [5]. It is estimated that plants contain over 200,000 metabolites, with a single species potentially possessing 7,000–15,000 different metabolites [5].

Table 1: Core Omics Technologies at a Glance

| Omics Layer | Molecule Studied | Key Technologies | Primary Readout | Application in Plant Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics | DNA | NGS, GWAS | Genetic sequence, variants | Identifying genes for traits, marker discovery |

| Transcriptomics | RNA | RNA-seq, scRNA-seq | Gene expression levels | Understanding regulatory responses to environment |

| Proteomics | Proteins | LC-MS/MS, 2D-Gels | Protein abundance & modification | Analyzing functional actors and signaling networks |

| Metabolomics | Metabolites | GC/LC-MS, NMR | Metabolic composition & flux | Phenotyping, stress response, quality assessment |

Essential Bioinformatics Tools for Omics Data Analysis

The analysis of high-throughput omics data relies on a robust bioinformatics toolkit. The following tools are essential for handling, processing, and interpreting data from each omics layer.

Table 2: Key Bioinformatics Tools for Omics Data Analysis

| Tool Name | Primary Application | Best For | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BLAST | Sequence similarity search | Genomics, Comparative genomics | Highly reliable, free, widely integrated [6] | Can be slow for very large datasets |

| Bioconductor | Genomic data analysis | Transcriptomics, Statistical analysis | Comprehensive R-based suite, highly customizable [6] | Steep learning curve for non-R users [6] |

| Clustal Omega | Multiple sequence alignment | Genomics, Phylogenetics | User-friendly, fast for large alignments [6] | Performance drops with highly divergent sequences [6] |

| Galaxy | Workflow creation | All omics, Beginners | No-code, web-based interface, reproducible [6] | Limited advanced features vs. command-line tools [6] |

| DeepVariant | Variant calling | Genomics, Personalized medicine | AI-driven for high accuracy [6] [7] | Computationally intensive, complex setup [6] |

| Rosetta | Protein structure prediction | Proteomics, Drug design | AI-driven protein modeling [6] | Licensing fees for commercial use [6] |

| KEGG | Pathway analysis | All omics, Systems biology | Extensive pathway database [6] | Subscription required for full access [6] |

| Pathview | Multi-omics visualization | Data Integration | Painting data onto pathway diagrams [8] | Uses manually drawn "uber" pathway diagrams [8] |

Emerging trends are shaping the future of these tools, including the integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI). AI is now powering genomics analysis, increasing accuracy by up to 30% while cutting processing time in half in some applications [7]. Furthermore, large language models are being explored to "translate" nucleic acid sequences, unlocking new opportunities to analyze DNA, RNA, and downstream amino acid sequences [7].

Multi-Omics Data Integration: Methods and Workflows

Integration of multi-omics data is a critical step toward a holistic, systems-level understanding of plant biology. The integration allows researchers to link variations at the genetic level to functional outcomes, uncovering regulatory networks and causal mechanisms.

Integration Approaches and Tutorial

A recommended best-practice tutorial for genomic data integration consists of six consecutive steps [3]:

- Designing the Data Matrix: Formatting genes as 'biological units' and omics data (e.g., expression, methylation) as 'variables' [3].

- Formulating the Biological Question: Defining whether the goal is description, selection (of biomarkers), or prediction [3].

- Selecting a Tool: Choosing an integration method suited to the question and data type.

- Preprocessing the Data: Addressing missing values, outliers, normalization, and batch effects.

- Conducting Preliminary Analysis: Performing descriptive statistics and single-omics analysis to understand data structure.

- Executing Genomic Data Integration: Applying the chosen integration method.

Visualization of Integrated Data

Visualization is key to interpreting multi-omics data. Tools like the multi-omics Cellular Overview within the Pathway Tools (PTools) software enable simultaneous visualization of up to four omics datasets on organism-scale metabolic charts [8]. Different omics datasets can be painted onto different "visual channels" of the metabolic-network diagram; for example, transcriptomics data as reaction arrow color, proteomics data as arrow thickness, and metabolomics data as metabolite node color [8].

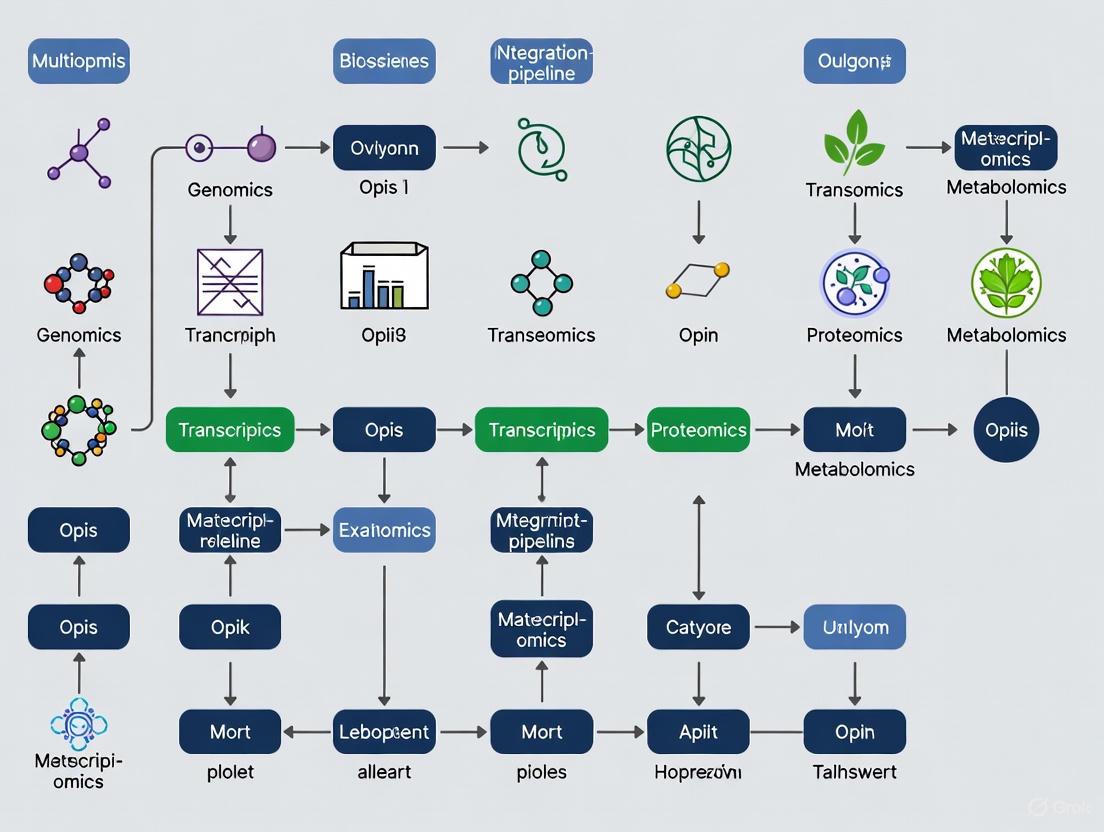

Multi-omics data integration workflow

Pathway Enrichment Analysis

A standard method for interpreting various types of omics data is pathway enrichment analysis, which identifies biological pathways that are significantly impacted in a given dataset [4]. There are three main statistical approaches:

- Over-representation Analysis (ORA): Tests whether genes in a pre-defined list (e.g., differentially expressed genes) are enriched in certain pathways more than expected by chance.

- Functional Class Scoring (FCS): Uses genome-wide scores (e.g., all expression values) rather than a fixed list, which can be more sensitive.

- Pathway Topology-based Methods: Incorporates information about the interactions and positions of molecules within a pathway, providing more biologically contextualized results [4].

Experimental Protocols for Key Omics Workflows

Protocol: LC-MS-Based Plant Metabolomics

Objective: To comprehensively profile primary and secondary metabolites from plant tissue.

Materials:

- Tissue Lyser: For homogenizing frozen plant tissue.

- Liquid Chromatography System: Coupled to a high-resolution mass spectrometer (e.g., Q-TOF or Orbitrap) [5].

- Extraction Solvents: Pre-chilled methanol, acetonitrile, and water (often in specific ratios like 2:2:1).

- Internal Standards: A mix of stable isotope-labeled compounds for quality control and quantification.

Method:

- Sample Collection and Quenching: Rapidly harvest and flash-free plant material (e.g., leaf disc) in liquid nitrogen to instantaneously halt metabolic activity.

- Homogenization: Grind frozen tissue to a fine powder under liquid nitrogen using a pestle and mortar or a tissue lyser.

- Metabolite Extraction: Weigh ~50 mg of powdered tissue into a pre-cooled tube. Add 1 mL of pre-chilled extraction solvent (e.g., methanol:accentonitrile:water, 2:2:1, v/v) and vortex vigorously. Incubate for 10 minutes on ice.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge at high speed (e.g., 14,000 x g) for 15 minutes at 4°C to pellet insoluble debris.

- Supernatant Collection: Transfer the clear supernatant to a new vial. Evaporate the solvent under a gentle stream of nitrogen or using a vacuum concentrator.

- Reconstitution: Reconstitute the dried metabolite pellet in a volume of LC-MS compatible solvent (e.g., 100 µL of 10% methanol) suitable for injection.

- LC-MS Analysis:

- Chromatography: Separate metabolites on a reverse-phase C18 column using a water-acetonitrile gradient containing 0.1% formic acid.

- Mass Spectrometry: Acquire data in both positive and negative electrospray ionization (ESI) modes with a mass range of 50-1500 m/z. Use data-dependent acquisition (DDA) to fragment top ions for metabolite identification.

- Data Processing: Use software (e.g., XCMS, MS-DIAL) for peak picking, alignment, and annotation against spectral libraries (e.g., MassBank, GNPS).

LC-MS plant metabolomics workflow

Protocol: Multi-Omics Integration with mixOmics

Objective: To integrate transcriptomic and metabolomic data from a poplar stress study to identify key genes and metabolites [3].

Materials:

- Omics Datasets: A data matrix with genes as rows and transcriptomic (e.g., mRNA-seq counts) and metabolomic (e.g., peak intensities) data as columns [3].

- Software Environment: R statistical computing environment.

- R Packages:

mixOmicspackage (version 6.18.1 or higher).

Method:

- Data Matrix Construction: Create a data matrix where rows correspond to genes and columns correspond to variables from multiple omics datasets (e.g., gene expression and methylation levels across different populations) [3].

- Data Preprocessing: Log-transform and normalize transcriptomics data (e.g., TPM or FPKM counts). Pareto-scale metabolomics data. Perform mean-centering on both datasets.

- Preliminary Analysis: Conduct Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on each dataset individually to assess overall structure and identify potential outliers.

- Integration with DIABLO: Use the Data Integration Analysis for Biomarker discovery using Latent cOmponents (DIABLO) framework within

mixOmics.- Set up the design matrix to define the connection between datasets.

- Tune the parameters (number of components and selectable features) using

tune.block.splsdato optimize performance. - Run the final

block.splsdamodel.

- Visualization and Interpretation:

- Generate a clustered image map (CIM) to visualize the correlation network between selected genes and metabolites across the multi-omics components.

- Use the

plotVarfunction to examine the correlation circle plot, showing how variables from both datasets contribute to the shared components. - Extract the list of variables with high loadings on each component as potential master regulators or key biomarkers [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Omics Workflows

| Category/Item | Specific Example | Function in Omics Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Kits | Illumina DNA Prep | Prepares genomic DNA for NGS sequencing on platforms like NovaSeq. |

| RNA Extraction Kits | QIAGEN RNeasy Plant Mini Kit | Isolates high-quality, intact total RNA from challenging plant tissues. |

| Library Prep Kits | TruSeq Stranded mRNA Kit | Converts purified RNA into sequencing-ready libraries for transcriptomics. |

| Mass Spectrometry | Trypsin, Protease | Digests proteins into peptides for LC-MS/MS analysis in proteomics. |

| Metabolite Standards | Stable isotope-labeled amino acids | Serves as internal standards for accurate quantification in metabolomics. |

| Chromatography Columns | C18 reverse-phase UHPLC columns | Separates complex mixtures of metabolites or peptides prior to MS detection. |

| Bioinformatics Platforms | Scispot, Galaxy | Manages multi-omics data, integrates pipelines, and ensures traceability [9]. |

The omics toolbox provides a powerful and ever-evolving suite of technologies that are fundamental to advancing plant research. The individual strengths of genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics are multiplied when these layers are integrated through robust bioinformatics pipelines and visualization tools. This multi-omics approach is driving innovations in crop improvement, sustainable agriculture, and optimized farming practices by providing a systems-level understanding of the genetic, epigenetic, and metabolic bases of key agronomic traits [1]. As these technologies continue to develop, with increasing automation and the integration of AI, they promise to further accelerate the pace of discovery and application in plant science.

The advent of high-throughput technologies has revolutionized plant biology, generating vast amounts of data across multiple molecular layers. Single-omics approaches—focusing exclusively on genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, or metabolomics—provide valuable but fundamentally limited insights into biological systems. These limitations arise because biological functions emerge from complex, dynamic interactions between molecules that single-layer analyses cannot capture [10]. Multi-omics integration has thus emerged as a critical paradigm, enabling researchers to construct comprehensive models of plant biology by simultaneously analyzing multiple data types. This approach is particularly valuable for understanding complex traits in crop species, where agronomic important characteristics like yield, stress resilience, and nutritional quality are governed by intricate molecular networks [1].

The fundamental weakness of single-omics studies lies in their inherent inability to reflect the cascading relationships and regulatory mechanisms that connect the genome to the phenome. While genomics provides a blueprint, transcriptomics reveals gene expression patterns, proteomics identifies functional effectors, and metabolomics characterizes biochemical outputs, none alone can reconstruct the complete biological narrative [10]. This integrated perspective is especially crucial when studying plant-pathogen interactions, where both host and pathogen molecular systems undergo rapid, coordinated changes during infection [10].

Limitations of Single-Omics Approaches

Single-omics approaches, while powerful for targeted investigations, present significant limitations that can lead to incomplete or misleading biological conclusions.

Incomplete Biological Picture

Each omics layer captures only a partial snapshot of cellular activity:

- Genomics identifies potential genetic determinants but cannot reveal how these elements are dynamically regulated in response to environmental cues or developmental signals [10].

- Transcriptomics measures RNA abundance but often correlates poorly with protein levels due to post-transcriptional regulation, translation efficiency, and protein turnover rates [10].

- Proteomics identifies functional proteins but cannot capture the metabolic activities they regulate or the biochemical phenotypes that result from their activity [1].

- Metabolomics provides the most direct readout of physiological status but offers limited insight into the regulatory mechanisms controlling metabolic fluxes [11].

Documented Disconnects Between Omics Layers

Several studies highlight the perils of relying on single-omics data. In potato roots infected with Spongospora subterranea, genes highly upregulated in resistant cultivars showed no corresponding increase in protein abundance, suggesting significant post-transcriptional regulation that would be missed by transcriptomics alone [10]. Similarly, a study on Leptosphaeria maculans identified 11 fungal genes highly upregulated during canola infection that, when disrupted via CRISPR-Cas9, proved non-essential for pathogenicity—a finding that contradicted the transcriptomic data in isolation [10]. These cases demonstrate how single-omics approaches can identify candidate genes or pathways that fail functional validation due to compensation, regulation at other biological layers, or incorrect inference of causal relationships.

Table 1: Documented Limitations of Single-Omics Approaches in Plant Research

| Omics Approach | Specific Limitations | Documented Example |

|---|---|---|

| Genomics | Static information; cannot capture dynamic responses; functional annotation often incomplete | Large, poorly annotated genomes in non-model plants hinder gene function prediction [12] |

| Transcriptomics | Poor correlation with protein abundance; misses post-translational regulation | Resistant potato cultivars showed upregulated genes without corresponding protein increases [10] |

| Proteomics | Limited coverage of low-abundance proteins; technical challenges in quantification | Fungal genes upregulated during infection were non-essential for pathogenicity [10] |

| Metabolomics | Difficult to infer upstream regulatory mechanisms; chemical diversity challenges detection | Metabolic changes without corresponding genomic context provide limited breeding value [1] |

Multi-Omics Integration Frameworks and Protocols

Multi-omics integration strategies can be systematically categorized into three progressive levels of complexity, each with distinct methodologies and applications.

Level 1: Element-Based Integration

Level 1 integration employs statistical methods to identify relationships between individual elements across different omics datasets without incorporating prior biological knowledge [12]. This approach is particularly valuable for discovery-based research where underlying mechanisms are poorly understood.

Protocol: Correlation-Based Integration for Abiotic Stress Response

- Data Preparation: Generate normalized transcriptomics and metabolomics datasets from control and stress-treated plant tissues (e.g., salt-stressed roots).

- Statistical Analysis: Calculate pairwise correlation coefficients (Pearson or Spearman) between all transcripts and metabolites.

- Significance Thresholding: Apply false discovery rate (FDR) correction to identify statistically significant correlations.

- Network Construction: Build bipartite networks connecting transcripts and metabolites with strong correlations (> |0.8|).

- Validation: Select key correlations for experimental validation (e.g., using mutant lines or targeted metabolomics).

This approach successfully identified salt tolerance mechanisms in upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) by correlating transcript and metabolite profiles [12].

Level 2: Pathway-Based Integration

Level 2 integration maps multi-omics data onto established biological pathways, leveraging prior knowledge to interpret results in functional contexts [12]. This strategy helps researchers understand how coordinated changes across molecular layers influence specific biological processes.

Protocol: Pathway Mapping for Defense Response Studies

- Pathway Database Selection: Choose an appropriate pathway database (KEGG, MetaCyc, MapMan) based on the target organism.

- Data Mapping: Annotate and map transcripts, proteins, and metabolites to their respective pathways.

- Enrichment Analysis: Perform statistical enrichment tests to identify pathways significantly perturbed in the experimental condition.

- Multi-Layer Visualization: Use tools like PathVisio or Cytoscape to create integrated pathway diagrams showing all omics layers simultaneously.

- Biological Interpretation: Interpret observed changes in the context of pathway functionality and cross-talk.

This method revealed key defense pathways in soybean (Glycine max) during fungal infection by integrating transcriptomic and metabolomic data [12].

Level 3: Mathematical Integration

Level 3 integration represents the most sophisticated approach, using mathematical modeling to generate quantitative, predictive models of biological systems [12]. These models can simulate system behavior under different conditions and generate testable hypotheses.

Protocol: Genome-Scale Metabolic Modeling for Crop Improvement

- Network Reconstruction: Assemble a genome-scale metabolic network using genomic annotation and biochemical databases.

- Multi-Omics Constraint: Integrate transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data as constraints on reaction fluxes.

- Model Simulation: Use flux balance analysis (FBA) or related techniques to predict metabolic fluxes under different conditions.

- Gene Knockout Simulation: In silico predict the effects of gene knockouts or overexpression on metabolic phenotypes.

- Experimental Validation: Design wet-lab experiments to test key model predictions.

This approach has been used to optimize L-phenylalanine production in engineered Escherichia coli [11] and can be adapted for biofortification studies in crops.

Table 2: Multi-Omics Integration Levels and Their Applications

| Integration Level | Key Methods | Example Applications | Software/Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1: Element-Based | Correlation analysis, clustering, multivariate statistics | Identifying novel transcript-metabolite relationships in stress responses | Pearson/Spearman correlation, k-means clustering, DIABLO [12] |

| Level 2: Pathway-Based | Pathway mapping, co-expression network analysis | Understanding system-level responses to pathogen infection | KEGG, MapMan, PathVisio, WGCNA [12] |

| Level 3: Mathematical | Genome-scale modeling, flux balance analysis | Predicting metabolic engineering targets for biofortification | Constraint-based reconstruction and analysis [12] |

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Successful multi-omics studies require specialized reagents and computational tools designed to handle diverse data types and integration challenges.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Omics Studies

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Multi-Omics Research |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina, PacBio, Nanopore | Generate genomic and transcriptomic data with varying read lengths and applications [10] |

| Mass Spectrometry Systems | LC-MS, GC-MS platforms | Identify and quantify proteins and metabolites with high sensitivity and resolution [12] |

| Integration Software | Omics Dashboard, MixOmics, MetaboAnalyst | Visualize and statistically integrate multiple omics datasets [11] |

| Pathway Databases | KEGG, MetaCyc, BioCyc | Provide curated biological pathways for functional annotation and interpretation [11] |

| Specialized Algorithms | WGCNA, MCIA, OnPLS | Perform specialized statistical integration of heterogeneous omics data types [12] |

Visualization of Multi-Omics Integration Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for multi-omics integration in plant research, showing how data from different molecular layers can be combined to generate biological insights:

Case Study: Multi-Omics in Plant-Pathogen Interactions

Plant-pathogen interactions represent an ideal application for multi-omics approaches due to the complexity of the interacting systems. The following diagram illustrates how different omics layers contribute to understanding disease mechanisms:

This integrated perspective enables researchers to move beyond simplistic models of disease resistance to understand the complex molecular dialogues between plants and pathogens. For example, multi-omics approaches have revealed how pathogens manipulate host hormone signaling and how plants recognize pathogen effectors to activate immune responses [10]. These insights provide new targets for breeding disease-resistant crops and developing sustainable crop protection strategies.

Application Note: Multi-Omics Profiling of Plant Stress Responses

Key Biological Insights from Integrated Data Analysis

Integrative multi-omics analyses have revealed that plants employ sophisticated, layered molecular strategies when confronting abiotic and biotic challenges. These responses involve coordinated changes across genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic levels, forming complex regulatory networks that determine stress outcomes [10] [13].

Table 1: Key Stress-Responsive Molecular Pathways Identified via Multi-Omics Integration

| Stress Type | Regulatory Pathways Activated | Key Molecular Players | Omics Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drought | ABA signaling, osmotic regulation | Proline, raffinose, ABA biosynthesis genes | Transcriptomics: Upregulated ABA genes; Metabolomics: Osmoprotectant accumulation [13] [14] |

| Pathogen Infection | Salicylic acid, jasmonic acid/ethylene pathways | Pathogen-recognition receptors, ROS production, PR proteins | Transcriptomics: Defense gene activation; Proteomics: Pathogenesis-related proteins [10] |

| Heat Stress | Photosynthesis downregulation, HSP activation | Heat shock proteins, antioxidant metabolites | Proteomics: HSP accumulation; Metabolomics: Antioxidant compounds [13] |

| Waterlogging | ABA responses, anaerobic metabolism | Fermentation enzymes, ethylene response factors | Hormonomics: ABA accumulation; Transcriptomics: Anaerobic genes [13] |

| Combined Stress | Unique signatures distinct from individual stresses | Specific transcription factor combinations | Integrated analysis: Novel regulatory networks [13] |

Experimental Validation of Multi-Omics Insights

Research demonstrates that single-omics approaches often provide incomplete pictures of plant stress responses. For instance, when investigating potato defense responses to the soilborne pathogen Spongospora subterranea, researchers observed that genes highly upregulated in resistant cultivars at the transcript level showed no corresponding increases in protein levels [10]. Similarly, another study disrupting 11 genes from Leptosphaeria maculans that were highly upregulated during infection found none were essential for fungal pathogenicity, highlighting the limitations of relying solely on transcriptomic data [10].

Protocol: Multi-Omics Integration for Plant Stress Research

Comprehensive Workflow for Multi-Omics Investigation

This protocol outlines a standardized pipeline for conducting integrated multi-omics analysis of plant stress responses, suitable for both abiotic and biotic stress research.

Sample Preparation and Experimental Design

- Plant Material Selection: Use genetically uniform plant materials. For crop studies, cv. 'Désirée' potato serves as a well-characterized model [13].

- Stress Application: Apply controlled stress conditions (drought, heat, waterlogging, pathogen inoculation) individually and in combination to mimic field conditions [13].

- Temporal Sampling: Collect leaf/tissue samples at multiple timepoints during stress application and recovery phases [13].

- Replication: Include minimum 5 biological replicates per condition to ensure statistical power [13].

- Sample Preservation: Immediately flash-freeze samples in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C until analysis.

Omics Data Generation

Genomics & Epigenomics:

- Extract high-molecular-weight DNA using CTAB protocol

- Perform whole-genome sequencing using long-read technologies (PacBio, Nanopore) for improved assembly [14]

- Conduct bisulfite sequencing for DNA methylation analysis and ChIP-seq for histone modifications [14]

Transcriptomics:

- Isolate total RNA using commercial kits with DNase treatment

- Construct libraries for bulk RNA-seq or single-cell RNA-seq using 10× Genomics platform [15]

- For scRNA-seq: Prepare protoplasts via enzymatic digestion of plant cell walls [15]

Proteomics:

- Extract proteins using phenol-based method

- Perform tryptic digestion followed by data-independent acquisition mass spectrometry [14]

- Conduct phosphoproteomics using TiO₂ enrichment for phosphorylation analysis [14]

Metabolomics & Hormonomics:

- Extract metabolites using methanol:water:chloroform system

- Analyze via LC-MS for comprehensive profiling and GC-MS for primary metabolites [13]

- Perform targeted analysis for phytohormones (ABA, jasmonates, salicylic acid) [13]

Data Integration and Computational Analysis

- Preprocessing: Use specialized tools (Cell Ranger for scRNA-seq, MaxQuant for proteomics) for platform-specific data processing [15]

- Multi-Omics Integration: Apply machine learning pipelines incorporating statistical frameworks and knowledge networks [13]

- Network Analysis: Reconstruct regulatory networks using tools like Seurat and SCANPY [15]

- Pathway Mapping: Visualize enriched pathways using KEGG and Plant Reactome resources

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Plant Multi-Omics Studies

| Category | Specific Product/Platform | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Platforms | PacBio Sequel, Oxford Nanopore | Long-read sequencing for structural variant detection [14] |

| Single-Cell Technologies | 10× Genomics Chromium | Single-cell RNA sequencing platform for cellular heterogeneity [15] |

| Mass Spectrometry | LC-MS/MS systems (Q-Exactive, timsTOF) | Protein identification, quantification, and metabolite profiling [14] |

| Protoplast Isolation | Cellulase and Pectinase enzymes | Enzymatic digestion of plant cell walls for single-cell protocols [15] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Seurat, SCANPY, Cell Ranger | Single-cell data analysis, clustering, and cell type identification [15] |

| Plant Growth Regulators | Abscisic acid, jasmonic acid, salicylic acid | Phytohormone standards for hormonomics analysis [13] |

Advanced Visualization of Stress Signaling Pathways

Protocol Modifications for Specific Research Applications

Pathogen Interaction Studies

For plant-pathogen investigations, modify the standard protocol to include:

- Dual RNA-seq: Simultaneously profile both plant and pathogen transcriptomes during infection [10]

- Spatial Transcriptomics: Map gene expression patterns maintaining tissue context during pathogen invasion [15]

- Effector Proteomics: Identify pathogen-secreted effector proteins using apoplast fluid extraction and MS analysis [10]

- Time-Course Design: Increase sampling frequency during early infection stages to capture rapid defense responses

Single-Cell and Spatial Omics Adaptations

- Protoplast vs Nuclei Isolation: For tough tissues (xylem), use nuclei isolation instead of protoplasts to avoid digestion bias [15]

- Spatial Transcriptomics: Combine imaging and sequencing to maintain spatial context of stress responses [15]

- Multiome Assays: Implement simultaneous scRNA-seq + snATAC-seq for linked gene expression and chromatin accessibility data [15]

Data Integration Special Considerations

- Cross-Species Alignment: For pathogen studies, create composite reference genomes for proper read assignment [10]

- Temporal Alignment: Develop computational methods to synchronize timepoints across omics layers with different temporal resolutions

- Causal Inference: Apply Bayesian networks and machine learning to distinguish correlation from causation in stress response pathways [10]

The integration of multi-omics data represents a paradigm shift in plant systems biology, enabling unprecedented insights into the molecular mechanisms governing agronomic traits, stress responses, and pathogen interactions [1] [10]. By combining datasets from genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, researchers can achieve a more comprehensive understanding of biological systems than single-omics approaches can provide [16]. However, this integrative approach faces three fundamental challenges that complicate analysis and interpretation: the inherent data heterogeneity arising from different technological platforms; the extreme dimensionality where variables vastly outnumber samples; and the profound biological complexity of plant systems, including diverse secondary metabolites, large genomes, and intricate regulatory networks [17] [18]. Addressing these challenges requires sophisticated computational frameworks and methodological strategies to effectively harness the potential of multi-omics data for advancing plant research and breeding programs.

Deconstructing the Core Challenges

Data Heterogeneity: The Multi-Platform Dilemma

Data heterogeneity in multi-omics studies stems from measuring fundamentally different biological entities using diverse technological platforms, each with distinct data distributions, scales, and formats [17]. This heterogeneity manifests in two primary dimensions: technical and biological.

Technical heterogeneity arises from platform-specific differences. Genomic data from sequencing platforms (Illumina, Nanopore) consists of discrete variant calls or read counts, while transcriptomic data (from RNA-seq) represents continuous expression values. Proteomic data from mass spectrometry provides quantitative protein abundance measurements, and metabolomic data (from GC-/LC-MS) captures concentrations of small molecules [16] [18]. Each data type requires specific normalization, transformation, and quality control procedures before integration can occur.

Structural heterogeneity is categorized as either horizontal or vertical. Horizontal datasets are generated from one or two technologies across diverse populations, representing high biological and technical heterogeneity. Vertical data involves multiple technologies probing different omics layers (genome, transcriptome, proteome, metabolome) to address comprehensive research questions [17]. The integration techniques applicable to one structural type often cannot be directly applied to the other, necessitating flexible computational approaches.

Table 1: Types of Data Heterogeneity in Multi-Omics Studies

| Heterogeneity Type | Source | Manifestation | Impact on Integration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technical | Different measurement platforms | Varying data distributions, scales, and noise levels | Requires platform-specific preprocessing and normalization |

| Biological | Different molecular entities | Distinct biological meanings and regulatory relationships | Challenges in establishing biologically meaningful connections |

| Structural Horizontal | Single technology across diverse populations | High biological variability | Needs methods robust to population heterogeneity |

| Structural Vertical | Multiple technologies across omics layers | Complementary but disparate data types | Requires fusion of fundamentally different data structures |

Dimensionality: The High-Dimension Low Sample Size (HDLSS) Problem

The dimensionality challenge in multi-omics integration is characterized by the "High-Dimension Low Sample Size" (HDLSS) problem, where the number of variables (p) significantly exceeds the number of biological samples (n) [17] [19]. This p>>n scenario creates statistical and computational obstacles that can compromise analytical outcomes.

In practical terms, a typical multi-omics study might involve hundreds of samples but tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands of variables across all omics layers. For example, in the Maize282 dataset, 279 lines were characterized using 50,878 genomic markers, 18,635 metabolomic features, and 17,479 transcriptomic features – totaling over 86,000 variables [19]. This high-dimensional space leads to the "curse of dimensionality," where distance metrics become less meaningful and the risk of model overfitting increases substantially.

The HDLSS problem necessitates specialized statistical approaches, as conventional methods assume n>p scenarios. Without appropriate regularization, machine learning algorithms tend to overfit these datasets, decreasing their generalizability to new data [17]. Additionally, high dimensionality amplifies multiple testing problems in significance analysis and increases computational demands for data processing and model training.

Biological Complexity: Plant-Specific Challenges

Plant systems present unique biological complexities that complicate multi-omics integration beyond the challenges faced in animal or microbial systems [18]. These include:

Genomic challenges: Many crop plants have large, complex, and often polyploid genomes that are poorly annotated, particularly for non-model species. This complicates the mapping of molecular features to biological functions [10] [18]. The presence of multi-organelles (chloroplasts, mitochondria) with their own genomes adds another layer of complexity to genomic integration.

Regulatory disconnects: Weak correlations between different molecular layers reveal intricate regulatory mechanisms. Studies consistently show poor correlations between transcript and protein levels (e.g., r=0.03 in salt-treated cotton, r=0.341 in methyl jasmonate-treated Persicaria minor), indicating significant post-transcriptional regulation [18]. This disconnect necessitates careful interpretation when integrating across omics layers.

Metabolic diversity: Plants produce an enormous array of secondary metabolites with complex biosynthetic pathways that are often species-specific and poorly characterized [18]. This diversity creates challenges for metabolite identification, annotation, and pathway mapping in metabolomic studies.

Temporal and spatial dynamics: Molecular responses to stimuli vary across tissues, cell types, and developmental stages. Single-cell and spatial omics technologies have revealed this previously unappreciated heterogeneity, showing that bulk tissue analyses may mask important cell-type-specific responses [10] [14].

Computational Frameworks and Integration Strategies

Classification of Integration Approaches

Multi-omics data integration strategies can be categorized into five distinct paradigms based on when and how different omics datasets are combined during analysis [17]. Each approach offers different advantages and limitations for addressing the core challenges of heterogeneity, dimensionality, and biological complexity.

Table 2: Multi-Omics Data Integration Strategies

| Integration Strategy | Description | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Integration | Concatenates all omics datasets into a single matrix before analysis | Simple implementation; captures all available data | Creates high-dimensional, noisy data; discounts dataset size differences |

| Mixed Integration | Transforms each omics dataset separately before combination | Reduces noise and dimensionality; handles data heterogeneities | May lose some inter-omics relationships during transformation |

| Intermediate Integration | Simultaneously integrates datasets to output common and omics-specific representations | Captures shared and unique patterns across omics layers | Requires robust preprocessing; computationally intensive |

| Late Integration | Analyzes each omics separately and combines final predictions | Avoids challenges of direct dataset fusion | Does not capture inter-omics interactions; may miss synergistic effects |

| Hierarchical Integration | Incorporates prior knowledge of regulatory relationships between omics layers | Most biologically informed; truly embodies trans-omics analysis | Limited generalizability; requires extensive prior knowledge |

Workflow for Addressing Multi-Omics Challenges

The following workflow diagram illustrates a systematic approach to tackling the core challenges in multi-omics integration:

Three-Level MOI Framework for Plant Systems

A systematic Multi-Omics Integration (MOI) framework for plant research can be implemented through three progressive levels of analysis [18]:

Level 1: Element-Based Integration - This unbiased approach uses correlation, clustering, and multivariate analyses to identify relationships between individual elements across omics datasets. Correlation analysis (Pearson, Spearman) identifies linear and ranked relationships between transcripts, proteins, and metabolites. While simple and intuitive, this approach often reveals the regulatory disconnects in plant systems, such as the weak overall correlations between transcript and protein levels observed in stress responses [18].

Level 2: Pathway-Based Integration - This knowledge-driven approach maps multi-omics data onto established biological pathways and networks. Methods include co-expression analysis integrated with metabolomics data, gene-metabolite network construction, and pathway enrichment analysis [16] [18]. For example, Weighted Correlation Network Analysis (WGCNA) can identify co-expressed gene modules that correlate with metabolite accumulation patterns, revealing regulated metabolic pathways [16].

Level 3: Mathematical Integration - The most sophisticated level uses quantitative modeling to generate testable hypotheses. This includes differential equation-based models and genome-scale metabolic networks (GSMNs) that simulate flux through metabolic pathways [18]. These models can predict system behavior under different genetic or environmental perturbations, though they require extensive curation for plant-specific pathways.

Experimental Protocols for Multi-Omics Integration

Protocol 1: Correlation-Based Integration of Transcriptomics and Metabolomics Data

This protocol enables the identification of relationships between gene expression and metabolite accumulation in plant systems under stress conditions or across developmental stages [16].

Materials and Reagents:

- Plant tissue samples (minimum 3 biological replicates per condition)

- RNA extraction kit (e.g., TRIzol, RNeasy Plant Mini Kit)

- LC-MS/MS or GC-MS system for metabolomics

- RNA sequencing library preparation reagents

- SOLiD, Illumina or other NGS platform for transcriptomics

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Harvest plant tissue under defined conditions, flash-freeze in liquid nitrogen, and store at -80°C until extraction.

- Transcriptomics Data Generation:

- Extract total RNA using appropriate kit, validate integrity (RIN > 8.0)

- Prepare RNA-seq libraries using standard protocols (e.g., Illumina TruSeq)

- Sequence on appropriate platform to obtain minimum 20 million reads per sample

- Process raw data: quality control (FastQC), alignment (STAR/Hisat2), quantification (featureCounts)

- Metabolomics Data Generation:

- Extract metabolites using methanol:water:chloroform (2:1:1) at -20°C

- Analyze using LC-MS/MS in both positive and negative ionization modes

- Identify and quantify metabolites against standards or databases (e.g., PlantCyc, KNApSAcK)

- Data Preprocessing:

- Normalize transcript counts using TPM or FPKM and apply variance-stabilizing transformation

- Normalize metabolomics data using probabilistic quotient normalization or similar

- Impute missing values using k-nearest neighbors or random forest methods

- Integration Analysis:

- Perform co-expression analysis on transcriptomics data using WGCNA to identify gene modules

- Calculate module eigengenes (first principal component) for each co-expression module

- Correlate module eigengenes with normalized metabolite intensity patterns

- Construct gene-metabolite network using Cytoscape for visualization

- Identify significant correlations (FDR < 0.05) and link to biological pathways

Troubleshooting Tips:

- Weak correlations may indicate post-transcriptional regulation; consider adding proteomics layer

- Batch effects can confound integration; include technical controls and use ComBat or similar for correction

- Biological interpretation requires species-specific pathway databases; consult PlantGSEA or PlantReactome

Protocol 2: Multi-Omics Enhanced Genomic Prediction

This protocol integrates multiple omics layers to improve genomic selection models in plant breeding programs, particularly for complex traits influenced by multiple biological processes [19].

Materials and Reagents:

- Plant population with genomic, transcriptomic, and metabolomic data

- High-performance computing resources

- R or Python with appropriate ML libraries (scikit-learn, TensorFlow, tidymodels)

- Phenotypic data for target traits

Procedure:

- Data Collection and Preprocessing:

- Collect genomic data (SNP markers), transcriptomic data (RNA-seq), and metabolomic data (MS-based) for training population

- Ensure all omics data are from the same biological samples and conditions

- Perform quality control: remove markers with high missingness (>20%), low MAF (<0.05)

- Normalize each omics dataset appropriately for integration method

- Integration Strategy Selection:

- For early integration: Concatenate all omics datasets into single feature matrix

- For mixed integration: Transform each dataset (e.g., PCA) before concatenation

- For intermediate integration: Use multi-view learning algorithms (e.g., MOFA)

- For late integration: Train separate models on each omics type and ensemble predictions

- Model Training:

- Split data into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) sets

- For genomic-only baseline: Implement GBLUP or Bayesian models

- For multi-omics: Use appropriate models (random forest, gradient boosting, neural networks)

- Perform hyperparameter tuning using validation set

- Model Evaluation:

- Predict traits on test set and calculate predictive accuracy (correlation between predicted and observed)

- Compare multi-omics models against genomic-only baseline

- Assess model stability through cross-validation (5-10 folds)

- Biological Interpretation:

- Extract feature importance scores from trained models

- Identify key molecular features from different omics layers contributing to prediction

- Map important features to biological pathways using enrichment analysis

Application Notes:

- Model-based fusion approaches generally outperform simple concatenation [19]

- Complex traits with nonlinear inheritance benefit most from multi-omics integration

- Computational demands increase with omics layers; consider distributed computing for large datasets

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Omics Studies

| Category | Item | Function | Example Products/Platforms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing | RNA Extraction Kits | High-quality RNA isolation for transcriptomics | RNeasy Plant Mini Kit, TRIzol |

| Library Prep Kits | cDNA library construction for NGS | Illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA | |

| NGS Platforms | High-throughput sequencing | Illumina NovaSeq, PacBio Sequel | |

| Mass Spectrometry | LC-MS Systems | Metabolite separation and detection | Thermo Q-Exactive, Agilent Q-TOF |

| GC-MS Systems | Volatile metabolite analysis | Agilent 8890-5977B GC/MSD | |

| Protein Preparation Kits | Protein extraction and digestion | Filter-Aided Sample Preparation | |

| Computational Tools | Integration Software | Multi-omics data analysis | MixOmics, MOFA, OmicsAnalyst |

| Network Visualization | Biological network mapping | Cytoscape, igraph | |

| Statistical Environments | Data processing and modeling | R/Bioconductor, Python | |

| Specialized Reagents | Isotope Labels | Metabolic flux analysis | 13C-glucose, 15N-ammonium |

| Enzyme Assays | Pathway validation | Antioxidant, phosphatase assays | |

| Antibody Panels | Protein validation | Western blot, ELISA kits |

Concluding Remarks

The integration of multi-omics data in plant research represents both a tremendous opportunity and a significant challenge. While data heterogeneity, dimensionality, and biological complexity present substantial obstacles, the development of sophisticated computational frameworks and experimental protocols is enabling researchers to extract unprecedented insights from these complex datasets. The systematic approaches outlined here—including the three-level MOI framework and specific experimental protocols—provide actionable strategies for addressing these core challenges. As multi-omics technologies continue to evolve and become more accessible, their integration will play an increasingly central role in advancing plant systems biology, breeding programs, and sustainable agricultural innovation.

Strategies and Tools for Multi-Omics Data Integration

Multi-omics integration has emerged as a transformative approach in plant systems biology, enabling a comprehensive understanding of molecular mechanisms governing key agronomic traits [1]. The complexity of biological systems, coupled with technological advances in high-throughput data generation, necessitates robust methodological frameworks to assimilate, annotate, and model large-scale molecular datasets [18]. Plant systems present unique challenges for integration, including poorly annotated genomes, metabolic diversity, and complex interaction networks, requiring specialized approaches beyond those used in human or microbial systems [18]. This protocol outlines three systematic levels of multi-omics integration—element-based, pathway-based, and mathematical frameworks—with detailed applications for plant research. These stratified approaches provide researchers with structured methodologies to extract meaningful biological insights from complex, multi-layered data, ultimately supporting advancements in crop improvement, stress resilience, and sustainable agriculture [1] [18].

Element-Based Integration (Level 1)

Conceptual Framework and Definition

Element-based integration represents the foundational level of multi-omics integration, focusing on statistical associations between individual molecular components across different omics layers [18]. This approach employs unbiased, data-driven methods to identify correlations and patterns without incorporating prior biological knowledge [18]. The primary advantage of element-based integration lies in its simplicity and intuitiveness, making it particularly suitable for initial explorations of datasets where comprehensive pathway annotations may be limited or unavailable [18]. In plant research, this level is especially valuable for non-model species with incomplete genomic annotations, as it can reveal novel relationships between transcripts, proteins, and metabolites that might not be evident through knowledge-dependent approaches [18].

Core Methodologies and Protocols

Correlation Analysis

The most fundamental element-based approach involves calculating correlation coefficients between different molecular entities across omics layers [18]. The standard protocol involves:

- Data Preprocessing: Normalize transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics datasets using appropriate scaling methods (e.g., variance stabilizing transformation, quantile normalization) to ensure comparability across platforms [18].

- Coefficient Calculation: Compute Pearson's correlation coefficients for linear relationships or Spearman's rank coefficients for monotonic non-linear relationships between all possible pairs of elements across omics datasets [18].

- Significance Testing: Apply false discovery rate (FDR) correction for multiple testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure with a threshold of FDR < 0.05 [18].

- Validation: For normally distributed data with skewness, implement Fisher's transformation to calculate corresponding correlation coefficients [18].

Table 1: Correlation Analysis Outcomes in Plant Studies

| Plant Species | Treatment/Condition | Transcript-Protein Correlation | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cotton (salt-tolerant and sensitive varieties) | Salt stress | r = 0.03 (very weak correlation) | Scarce correlation between transcript and protein patterns regardless of genotype [18] |

| Persicaria minor (herbal plant) | Methyl jasmonate (MeJA) hormone treatment | r = 0.341 (poor overall correlation) | Weak proteome-transcriptome correlation suggesting post-transcriptional regulation [18] |

| Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) | Fruit ripening process | Not well-correlated for ethylene pathway components | Suggests post-transcriptional and post-translational regulation for ripening pathways [18] |

Clustering Analysis

Unsupervised clustering methods group molecular elements with similar patterns across multiple omics datasets:

Protocol:

- Construct a combined data matrix with features from all omics layers.

- Apply k-means clustering or hierarchical clustering with Euclidean distance metrics.

- Determine optimal cluster numbers using the elbow method or silhouette analysis.

- Validate clusters through biological interpretation and functional enrichment.

Application Example: In a study on Bidens alba, clustering analysis of transcriptomics and metabolomics data revealed tissue-specific co-expression modules for flavonoids and terpenoids, identifying key biosynthetic genes including CHS, F3H, FLS, HMGR, FPPS, and GGPPS that corresponded with metabolite accumulation patterns [20].

Multivariate Analysis

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and related dimensionality reduction techniques represent powerful element-based integration methods:

Protocol:

- Standardize all variables to unit variance.

- Perform PCA on the combined multi-omics dataset.

- Identify influential features driving sample separation in principal component space.

- Interpret components through loading analysis and biplot visualization.

Application Example: In potato stress response studies, PCA integration of transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics data revealed distinct molecular signatures in response to heat, drought, and waterlogging stresses, showing a coordinated downregulation of photosynthesis across multiple molecular levels [13].

Case Study: Stress Response in Persicaria minor

A comprehensive element-based integration study on the medicinal plant Persicaria minor under methyl jasmonate (MeJA) elicitation demonstrated both the utility and limitations of this approach [18]. While overall transcript-protein correlation was weak (r=0.341), focused analysis revealed that defense-related proteins (proteases and peroxidases) showed significant positive correlation with their cognate transcripts, suggesting concerted molecular upregulation to overcome stress signals [18]. Conversely, growth-related proteins (photosynthetic and structural proteins) showed discordant patterns with significant suppression at the protein level but not at the transcript level, indicating potential post-transcriptional regulatory mechanisms in stress response [18].

Pathway-Based Integration (Level 2)

Conceptual Framework and Definition

Pathway-based integration represents an intermediate complexity approach that incorporates prior biological knowledge to connect multi-omics data within established metabolic, regulatory, or signaling pathways [18]. This method moves beyond simple statistical associations to place molecular changes in functional context, enabling more biologically meaningful interpretations of multi-omics data [18]. The approach is particularly powerful in plant systems where well-characterized pathways for secondary metabolism, stress response, and development provide frameworks for integration [18]. By mapping diverse molecular entities onto shared biological pathways, researchers can identify coordinated changes across omics layers and pinpoint key regulatory nodes that drive phenotypic outcomes [1].

Core Methodologies and Protocols

Co-expression Network Analysis

Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) represents a powerful pathway-based integration method:

Protocol:

- Construct separate co-expression networks for each omics data type using pairwise correlations between features.

- Identify modules of highly correlated features within each network.

- Calculate module eigengenes representing overall expression patterns.

- Correlate module eigengenes across omics layers to identify preserved co-expression modules.

- Annotate cross-omics modules using pathway databases (KEGG, PlantCyc, MetaCyc).

Application Example: In rice studies, integrated genomics and metabolomics identified key loci and metabolic pathways controlling grain yield and nutritional quality through co-expression network analysis [1].

Knowledge-Based Pathway Mapping

Direct mapping of multi-omics data onto established pathway databases:

Protocol:

- Annotate molecular features using KEGG, GO, PlantCyc, or species-specific databases.

- Calculate pathway enrichment statistics for differentially expressed features at each omics level.

- Identify pathways showing coordinated changes across multiple omics layers.

- Visualize multi-omics data on pathway maps using tools like Pathview or Cytoscape.

Application Example: In Bidens alba, integrated transcriptomics and metabolomics mapped onto flavonoid and terpenoid biosynthesis pathways revealed tissue-specific expression of biosynthetic genes (CHS, F3H, FLS, HMGR, FPPS, GGPPS) that directly correlated with metabolite accumulation patterns in different organs [20].

Case Study: Tissue-Specialized Metabolism in Bidens alba

A comprehensive pathway-based integration study on the medicinal plant Bidens alba investigated the organ-specific biosynthesis of flavonoids and terpenoids [20]. Researchers employed reference-guided transcriptomics and widely targeted metabolomics across four tissues (flowers, leaves, stems, and roots), identifying 774 flavonoids and 311 terpenoids with distinct tissue distribution patterns [20]. Pathway mapping revealed that flavonoids were predominantly enriched in aerial tissues, while specific sesquiterpenes and triterpenes accumulated preferentially in roots [20]. Through coordinated analysis of transcript and metabolite abundances across the phenylpropanoid, flavonoid, MVA, and MEP pathways, the study identified key biosynthetic genes (including CHS, F3H, FLS, HMGR, FPPS, and GGPPS) showing tissue-specific expression patterns that directly correlated with metabolite accumulation [20]. Furthermore, several transcription factors (BpMYB1, BpMYB2, and BpbHLH1) were identified as candidate regulators, with BpMYB2 and BpbHLH1 showing contrasting expression between flowers and leaves, suggesting complex regulatory mechanisms governing tissue-specialized metabolism [20].

Table 2: Pathway-Based Integration in Bidens alba Secondary Metabolism

| Pathway | Key Biosynthetic Genes Identified | Tissue-Specific Pattern | Major Metabolite Classes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flavonoid Biosynthesis | CHS, F3H, FLS | Enriched in aerial tissues (flowers, leaves) | Flavones, flavonols, anthocyanins |

| Terpenoid Biosynthesis (MVA pathway) | HMGR, FPPS | Root-specific expression for certain sesquiterpenes | Sesquiterpenes, triterpenes |

| Terpenoid Biosynthesis (MEP pathway) | GGPPS, DXR | High expression in flowers | Monoterpenes, diterpenes |

Mathematical Framework Integration (Level 3)

Conceptual Framework and Definition

Mathematical framework integration represents the most advanced level of multi-omics integration, employing sophisticated computational models to jointly analyze multiple omics datasets [18] [21]. These approaches can be broadly categorized into network-based and non-network-based methods, with Bayesian and multivariate statistical frameworks providing the mathematical foundation [21]. The primary strength of these methods lies in their ability to capture complex, non-linear relationships across omics layers while accounting for noise, missing data, and heterogeneous data structures [21]. In plant research, these frameworks are particularly valuable for predicting emergent properties of biological systems, identifying subtle but biologically important interactions, and generating testable hypotheses about system-level regulation [18] [21].

Core Methodologies and Protocols

Network-Based Bayesian Integration (NB-BY)

Bayesian networks provide a probabilistic framework for modeling causal relationships across omics layers:

Protocol:

- Define prior probability distributions based on existing biological knowledge.

- Structure learning to identify network topology from multi-omics data.

- Parameter estimation to quantify relationship strengths.

- Posterior probability computation using Bayes' rule to update beliefs based on observed data.

- Network validation through cross-validation and biological verification.

Application Example: In crop resilience studies, Bayesian networks have been used to integrate genomic, transcriptomic, and metabolic data to identify key regulatory circuits controlling drought tolerance in maize and cold adaptation in wheat [1] [21].

Multivariate Statistical Integration

Partial Least Squares (PLS) and related dimensionality reduction techniques:

Protocol:

- Preprocess and scale all omics datasets.

- Implement multi-block PLS (sMB-PLS) to identify latent variables that maximize covariance between omics blocks.

- Identify multi-dimensional regulatory modules containing sets of regulatory factors from different omics layers.

- Validate modules through permutation testing and biological relevance assessment.

Mathematical Foundation: Given n input layers X₁, X₂, X₃ and a response dataset Y measured on the same samples, sMB-PLS identifies common weights to maximize covariance between summary vectors of input matrices and the summary vector of the output matrix [21].

Machine Learning Integration

Random Forest and other ensemble methods for predictive modeling:

Protocol:

- Compile a feature matrix integrating selected variables from all omics layers.

- Train random forest classifiers or regressors to predict phenotypes of interest.

- Calculate feature importance metrics to identify influential variables across omics layers.

- Validate model performance through cross-validation and independent testing.

Application Example: In potato research, machine learning integration of phenotyping, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics data provided insights into responses to single and combined abiotic stresses, identifying downregulation of photosynthesis at different molecular levels as a conserved response across stress conditions [13].

Case Study: Abiotic Stress Response in Potato

A sophisticated mathematical integration study on potato (Solanum tuberosum cv. Désirée) investigated molecular responses to single and combined abiotic stresses (heat, drought, and waterlogging) [13]. Researchers established a bioinformatic pipeline based on machine learning and knowledge networks to integrate daily phenotyping data with multi-omics analyses comprising proteomics, targeted transcriptomics, metabolomics, and hormonomics at multiple timepoints during and after stress treatments [13]. The mathematical integration revealed that waterlogging produced the most immediate and dramatic effects, unexpectedly activating ABA responses similar to drought stress [13]. Distinct stress signatures were identified at multiple molecular levels in response to heat or drought and their combination, with a coordinated downregulation of photosynthesis observed across different molecular levels, accumulation of minor amino acids, and diverse stress-induced hormone profiles [13]. This mathematical framework approach provided global insights into plant stress responses that would not have been apparent through single-omics or simpler integration approaches, facilitating improved breeding strategies for climate-adapted potato varieties [13].

Table 3: Mathematical Framework Methods for Multi-Omics Integration

| Method Category | Specific Methods | Mathematical Foundation | Plant Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Network-Based Non-Bayesian (NB-NBY) | CNAmet, Conexic | Graph theory, network measures | Identification of regulatory sub-networks in stress response [21] |

| Network-Based Bayesian (NB-BY) | iCluster, Bayesian Networks | Bayesian inference, probability theory | Predictive modeling of complex trait architectures [21] |

| Network-Free Non-Bayesian (NF-NBY) | sMB-PLS, MCIA, Integromics | Multivariate statistics, dimension reduction | Integration of transcriptomics and metabolomics for trait discovery [21] |

| Network-Free Bayesian (NF-BY) | MDI, Bayesian Factor Analysis | Bayesian latent variable models | Identification of conserved response modules across species [21] |

Successful implementation of multi-omics integration requires both wet-lab reagents and computational resources. The following toolkit summarizes essential materials for plant multi-omics studies:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Plant Multi-Omics Studies

| Reagent/Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Sequencing Tools | FastPure Universal Plant Total RNA Isolation Kit, VAHTS Universal V6 RNA-seq Library Prep Kit | High-quality RNA extraction and library preparation for transcriptomics | Essential for non-model plants with diverse secondary metabolites [20] |

| Metabolomics Standards | Internal standard mixtures in 70% methanol, UPLC-MS/MS systems | Metabolite extraction, identification, and quantification | Critical for diverse plant secondary metabolites [20] |

| Proteomics Resources | LC-MS/MS systems, SWATH-MS protocols | Protein identification and quantification | Proteomics informed by transcriptomics (PIT) approach for non-model plants [18] |

| Reference Materials | Quartet Project reference materials (DNA, RNA, protein, metabolites) [22] | Quality control and cross-platform standardization | Enables ratio-based profiling for reproducible multi-omics integration [22] |

| Bioinformatics Databases | KEGG, GO, PlantTFDB, PlantCyc, Nr, Pfam, Uniprot | Functional annotation and pathway mapping | Particularly important for poorly annotated plant genomes [18] [20] |

| Computational Tools | DESeq2, WGCNA, MetaboAnalystR, Cytoscape, Random Forest | Data analysis, integration, and visualization | Machine learning for predictive model development [13] [20] |

The stratified framework for multi-omics integration—progressing from element-based to pathway-based to mathematical frameworks—provides plant researchers with a systematic approach to extract meaningful biological insights from complex molecular datasets [18]. Each level offers distinct advantages and addresses different biological questions, with the choice of integration strategy dependent on research objectives, data quality, and available computational resources [18] [21]. Element-based approaches offer simplicity and are ideal for initial data exploration, particularly in non-model species [18]. Pathway-based integration provides functional context and is powerful for understanding coordinated biological processes [18] [20]. Mathematical frameworks offer the most sophisticated approach for predictive modeling and identification of complex, non-linear relationships [21] [13].

As multi-omics technologies continue to advance, emerging layers such as epigenomics, single-cell omics, and spatial transcriptomics will further expand integration possibilities [1]. The development of standardized reference materials, like those from the Quartet Project, will enhance reproducibility and comparability across studies and laboratories [22]. For plant research specifically, continued development of species-specific databases and computational tools will be essential to address the challenges of large, poorly annotated genomes and diverse secondary metabolites [18]. By adopting these structured integration frameworks, plant scientists can accelerate the discovery of molecular mechanisms underlying key agronomic traits, ultimately supporting the development of improved crop varieties for sustainable agriculture [1].

In plant research, the transition from single-omics to multi-omics approaches has created a paradigm shift in understanding complex biological systems. A critical challenge in this domain is determining the optimal method for integrating diverse data types—genomics, transcriptomics, metabolomics, and phenomics—to maximize predictive accuracy and biological insight. Two predominant strategies have emerged: early fusion (concatenation-based methods) and model-based integration (sophisticated algorithmic fusion). This review provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of these approaches, highlighting their methodological foundations, performance characteristics, and practical applications within plant research pipelines.

Methodological Foundations

Early Fusion (Concatenation-Based Approach)

Early fusion, also known as data-level fusion or concatenation, involves combining raw or pre-processed data from multiple omics layers into a single feature matrix before model training [19] [23].

- Implementation: Data from genomics, transcriptomics, and metabolomics are merged horizontally, creating an extended feature space where each column represents a variable from one omics layer.

- Theoretical Basis: This approach operates on the premise that simultaneous input of all biological variables enables the model to capture potential inter-relationships between different molecular layers during the learning process.

- Technical Considerations: Successful implementation requires meticulous data preprocessing, including normalization, scaling, and dimensionality reduction to address the "curse of dimensionality" that arises from high feature-to-sample ratios [19].

Model-Based Integration (Structured Multimodal Fusion)

Model-based integration employs sophisticated algorithmic architectures that process each omics layer separately before combining their representations at various levels of abstraction [19] [23].

- Implementation: This approach utilizes specialized machine learning frameworks that maintain the structural integrity of each omics dataset while learning cross-omics interactions through dedicated fusion mechanisms.

- Theoretical Basis: By preserving modality-specific characteristics before integration, these methods can capture non-linear, hierarchical relationships between omics layers that may be lost in simple concatenation approaches.

- Technical Considerations: Model-based integration often requires more complex computational infrastructure and advanced tuning procedures but offers greater flexibility in modeling biological complexity [19].

Performance Comparison in Plant Research Applications

Predictive Accuracy Across Crop Species

Recent large-scale benchmarking studies across multiple crop species have revealed distinct performance patterns between early fusion and model-based integration strategies. The table below summarizes quantitative comparisons from implementing both approaches across different plant species:

Table 1: Performance comparison of fusion strategies across plant species

| Species | Trait Type | Early Fusion Accuracy | Model-Based Integration Accuracy | Performance Delta | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maize (282 lines) | Complex Agronomic Traits | Variable; often suboptimal | Consistently superior for complex traits | +12-15% improvement | [19] |

| Maize (368 lines) | Biomass-Related Traits | Inconsistent benefits | Robust performance across traits | +8-10% improvement | [19] [24] |

| Rice (210 lines) | Yield Components | Moderate accuracy gains | Highest accuracy achieved | +7-9% improvement | [19] |

| Arabidopsis | Flowering Time | Moderate prediction | Best performing model | Significant improvement | [25] |

| General Plant Classification | Species Identification | 72.28% (late fusion baseline) | 82.61% (automated fusion) | +10.33% improvement | [23] [26] |

Handling of Data Complexity and Dimensionality

The structural differences between integration approaches significantly impact their ability to manage complex omics data:

Table 2: Handling of data characteristics across integration strategies

| Data Characteristic | Early Fusion Approach | Model-Based Integration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Dimensionality | Prone to overfitting; requires aggressive dimensionality reduction | Built-in regularization; handles high dimensionality more effectively | |

| Heterogeneous Data Scales | Sensitive to normalization methods; combined scaling challenges | Modality-specific normalization preserves data structure | |

| Non-Linear Relationships | Limited capture of complex interactions | Superior modeling of non-additive and hierarchical relationships | |

| Missing Modalities | Complete case analysis required; imputation challenges | Robust architectures with techniques like multimodal dropout | [23] |

| Computational Demand | Lower computational requirements post-concatenation | Higher computational load during training | [19] |

| Biological Interpretability | Limited insight into cross-omics interactions | Enhanced capability for mechanistic insight | [19] [25] |

Experimental Protocols for Multi-Omics Integration

Protocol for Early Fusion Implementation

Materials Required:

- Multi-omics datasets (genomic, transcriptomic, metabolomic)

- Computational environment (R, Python)

- Data preprocessing tools (normalization, dimensionality reduction)

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing: Independently normalize each omics dataset using platform-specific methods (e.g., RMA for transcriptomics, parity scaling for metabolomics)

- Feature Selection: Apply dimensionality reduction techniques (PCA, PLS) to each omics layer to manage feature space

- Data Concatenation: Horizontally merge reduced dimension datasets into a unified matrix, maintaining sample alignment