Navigating Biological Variation: Strategies for Robust Plant Stress Response Studies

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and scientists to effectively handle biological variation in plant stress response studies.

Navigating Biological Variation: Strategies for Robust Plant Stress Response Studies

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and scientists to effectively handle biological variation in plant stress response studies. It explores the foundational sources of genetic and phenotypic diversity in plant systems, details advanced methodological approaches from genomics to phenomics for capturing this variation, addresses key troubleshooting strategies for experimental design, and outlines rigorous validation and comparative analysis techniques. By synthesizing current research and emerging technologies, this guide aims to enhance the reproducibility, accuracy, and translational potential of plant stress biology research for improved crop development and agricultural sustainability.

Understanding the Spectrum: Sources and Significance of Biological Variation in Plant Stress Responses

Technical Support Center: FAQs for Plant Stress Response Research

This guide addresses common challenges in experimental research that utilizes natural genetic variation to study plant stress responses.

Q1: My Arabidopsis lines show inconsistent fitness results across different field trials. Is this a failure of the experiment?

A: Not necessarily. This fluctuation may itself be a key finding. Research using isogenic Arabidopsis lines that varied only in specific glucosinolate (GSL) defense genes found that no single GSL genotype was the most fit across all environments or years. A genotype with high fitness in one location or year often showed lower fitness in another [1]. This indicates that environmental heterogeneity—fluctuating biotic and abiotic stressors—can maintain standing genetic variation within a species, meaning the variation itself is the adaptive trait [1].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Document Environmental Variables: Meticulously record abiotic (temperature, rainfall, soil composition) and biotic (pathogen load, insect herbivory) data for each trial location and season.

- Replicate Across Seasons: Always plan for multi-year field trials to distinguish consistent trends from environment-specific effects.

- Review Your Germplasm: Ensure that the lines being compared are nearly isogenic, differing primarily at your loci of interest, to confidently attribute fitness differences to the genetic variation under study rather than background variation [1].

Q2: How can I design an experiment to test plant responses to multiple concurrent stresses, which is more representative of field conditions?

A Moving from single-stress to multi-stress experiments is crucial, as plant responses to stress combinations can be unique and not predictable from single-stress responses [2].

- Key Considerations:

- Define the Stress Combination: Decide whether you are studying a simple combination (2-3 stresses) or a multifactorial stress combination (MFSC with ≥3 stresses), the latter being more representative of complex future climates [2].

- Control Timing and Intensity: The sequence, duration, and severity of applied stresses will significantly impact the plant's response [2].

- Measure Specific Pathways: Assess known integrative pathways, such as Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) homeostasis, which is a crucial hub in plant survival under stress combinations [2].

Q3: I've introgressed a beneficial allele from a wild relative into a cultivated crop, but yield has decreased. What went wrong?

A This is a common challenge in introgression breeding, often due to linkage drag—the co-introgression of tightly linked, deleterious genes from the wild donor parent [3].

- Solutions:

- Generate a Larger Population: Create a larger segregating population to increase the chance of identifying rare recombination events between the beneficial allele and nearby deleterious genes.

- Use Fine-Mapping: Employ molecular markers to finely map the location of your gene of interest and select progeny with smaller, more precise introgressed segments [3].

- Screen for Key Traits: In later generations, conduct careful phenotyping for yield components and other agronomic traits to select against lines with negative characteristics.

Q4: How can I effectively present quantitative data on genetic variation and trait correlations to a scientific audience?

A Effective data visualization is key to clear communication.

- Best Practices:

- Use the Full Axis: For bar charts of quantitative data, always start the numerical axis at zero to avoid visual distortion. This is less critical for line graphs [4].

- Limit Color Use: Use a maximum of six colors for categorical data. Avoid rainbow color scales for sequential data; instead, use a single-hue gradient from light to dark [4].

- Simplify and Label Directly: Remove unnecessary gridlines and legends where possible. Instead, label data lines or bars directly to reduce "visual math" for the reader [4].

Summarized Data from Key Studies

Table 1: Examples of Beneficial Alleles Introgressed from Wild Relatives for Crop Improvement

| Crop | Wild Donor Species | Introgressed Trait | Causal Gene / Locus (if known) | Functional Impact & Agronomic Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) | Solanum pennellii | Increased Fruit Sugar Content | Lin5 (cell wall invertase) | Alters sugar metabolism in developing fruit, significantly elevating sucrose levels [3]. |

| Tomato | Solanum chmielewskii | Enhanced Fruit Apocarotenoid Volatiles | CCD1B (carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase) | Modulates the production of volatile compounds derived from carotenoids, influencing flavor [3]. |

| Rice (Oryza sativa) | Oryza rufipogon | Increased Grain Yield | Multiple yield QTLs | Introgression of specific chromosomal segments from the wild species led to a dramatic 17% yield increase in the cultivated variety [3]. |

| Barley (Hordeum vulgare) | Hordeum vulgare ssp. spontaneum | Acid Soil Tolerance | HvAACT1 (Aluminum tolerance transporter) | A 1-kb transposon insertion regulates the expression of HvAACT1, boosting grain yield on acidic soils by enhancing aluminum tolerance [5]. |

| Maize (Zea mays) | Illinois Long-Term Selection Strains | Extreme Grain Protein/Oil Content | Multiple loci under long-term selection | Over 100 cycles of selection created populations with phenotypic extremes for composition, providing a resource for understanding storage metabolism [3]. |

Table 2: Documented Fitness Trade-offs of Natural Genetic Variants in Arabidopsis thaliana

| Gene / Pathway | Natural Variation Type | Fitness Benefit (in specific environments) | Fitness Cost / Trade-off (in other environments) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aliphatic Glucosinolate (GSL) Biosynthesis Genes (e.g., MAM, AOP) | Presence/Absence of specific chain-length or modified GSLs [1] | Enhanced defense against specialist insect herbivores [1]. | Allocation costs; potential susceptibility to generalist herbivores or other pathogen communities [1]. |

| Fluctuating GSL Genotypes | Combinations of polymorphic GSL genes [1] | High relative fitness in one field location or year due to prevailing biotic pressures [1]. | Lower relative fitness in a different location or across years, with no genotype being universally superior [1]. |

| Phytochrome-Interacting Factor (PIF4) / Phytochrome B (PHYB) | Regulatory alleles modulating seasonal growth [5] | Optimized growth in cold environments by precisely timing winter dormancy [5]. | Potential trade-off with maximum growth potential under ideal, non-stress conditions. |

| Ribosome-Associated Processes (e.g., AtPRMT3-RPS2B) | Regulatory variation [5] | Promotes ribosome biogenesis and cold adaptation [5]. | Coordinates a growth-stress trade-off, potentially limiting growth under non-stressful conditions [5]. |

Standardized Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Field-Based Fitness Assay for Natural Genetic Variants

Objective: To evaluate the fitness consequences of specific natural genetic variants in real-world environments [1].

- Germplasm Selection: Select or generate nearly isogenic lines (NILs) that are genetically identical except for the specific locus or loci of natural variation. This is critical for attributing fitness differences to the gene of interest [1].

- Experimental Design:

- Employ a randomized complete block design with sufficient replication.

- Include the recurrent parent (e.g., a standard accession like Col-0) as a control.

- Trial Execution:

- Conduct trials across multiple geographically distinct locations and over multiple growing seasons (at least 2-3 years).

- Record environmental data throughout the trial (temperature, precipitation, pest/pathogen incidence).

- Fitness Quantification:

- The primary fitness metric is total seed yield per plant.

- Secondary metrics can include survival to reproduction, silique (fruit) number, and plant biomass.

- Data Analysis: Use analysis of variance (ANOVA) to determine the effects of genotype, environment (location and year), and their interaction on fitness.

Protocol 2: Introgression of Alleles from Wild Germplasm

Objective: To transfer a beneficial allele from a wild plant relative into an elite cultivated background [3].

- Crossing:

- Make an initial cross between the cultivated recipient and the wild donor parent.

- Backcrossing:

- Backcross the F1 hybrid to the cultivated parent repeatedly (typically 3-6 generations) to recover the cultivated background. This creates a Backcross Inbred Line (BIL) population.

- Use Marker-Assisted Selection (MAS) during each backcross generation to select for the donor allele at the target locus and against other donor genome segments.

- Selfing:

- Self-pollinate selected lines to generate homozygous progeny for the introgressed segment.

- Phenotyping:

- Conduct rigorous lab and field-based phenotyping to confirm the expression of the desired trait and to check for any negative pleiotropic effects or linkage drag on agronomic traits like yield.

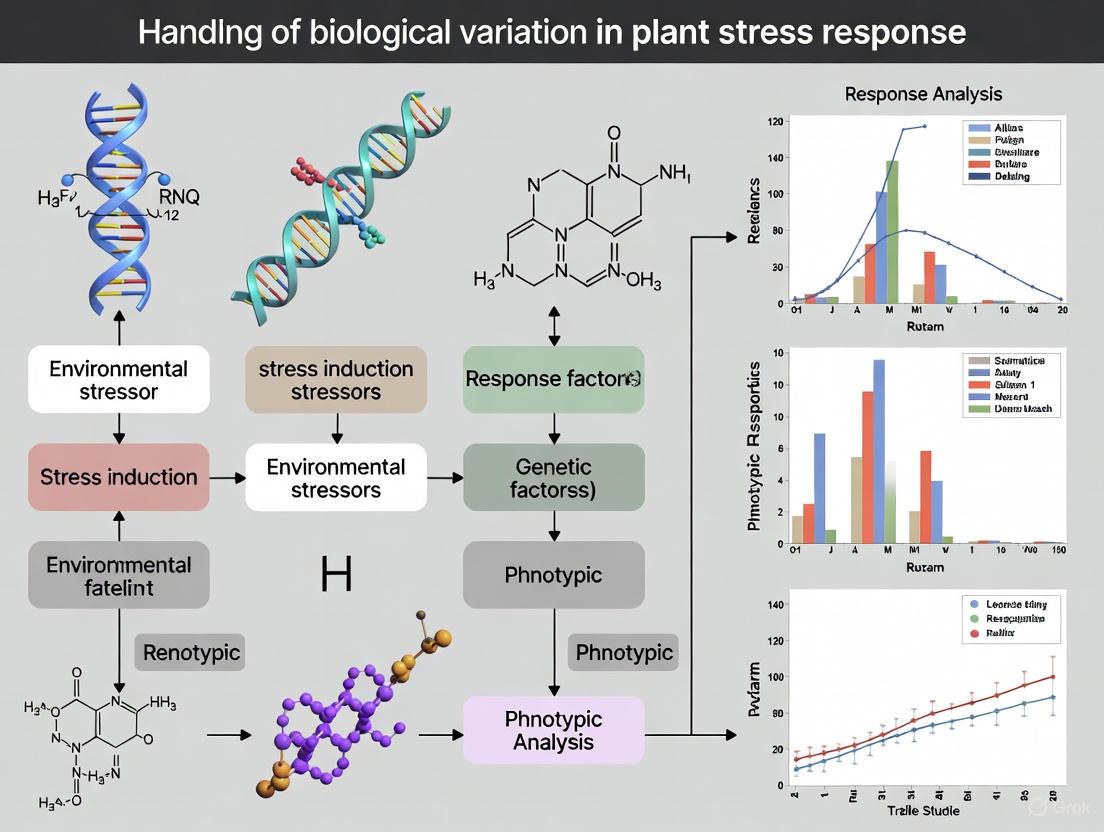

Research Concept and Workflow Visualizations

Diagram 1: Environmental variation maintains genetic diversity.

Diagram 2: Workflow for allele introgression from wild germplasm.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Studying Natural Genetic Variation

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis T-DNA Insertion Lines (e.g., from ABRC or NASC) | Used to create gene knockouts for functional validation of candidate genes identified from natural variation studies [1]. | Validating the role of a specific glucosinolate biosynthetic gene in herbivore resistance. |

| Introgression Line (IL) Libraries | Libraries of lines (e.g., in tomato, rice) where a single genomic segment from a wild donor is introgressed into a uniform cultivated background. They are powerful for directly linking phenotype to genotype [3]. | Identifying wild alleles that improve fruit sugar content or drought tolerance without the confounding effects of background genetic variation [3]. |

| Near-Isogenic Lines (NILs) | Lines that are genetically identical except for a small, targeted region containing the natural allele(s) of interest. The gold standard for confirming a gene's phenotypic effect [1]. | Conducting field fitness trials to compare the ecological performance of different alleles at a specific locus, as done with GSL genes in Arabidopsis [1]. |

| Reference Genome Sequences | High-quality genome assemblies for both model organisms and crop wild relatives. Essential for aligning re-sequencing data, identifying polymorphisms, and pinpointing causal variants [1] [3]. | Using the Arabidopsis thaliana Col-0 reference genome to identify single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in other accessions like Cape Verde Islands (Cvi) or Landsberg erecta (Ler). |

| Metabolomic Platforms (e.g., GC-MS, LC-MS) | Tools for the untargeted or targeted measurement of small molecules (metabolites). Crucial for connecting genetic variation to biochemical phenotype (chemotype), such as in studies of glucosinolates or fruit volatiles [3]. | Profiling the diverse aliphatic glucosinolates in different Arabidopsis accessions or analyzing tomato fruit volatiles in introgression lines [1] [3]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the main epigenetic mechanisms involved in plant stress memory? The primary epigenetic mechanisms that enable plants to "remember" past stress are DNA methylation (DM), histone modifications (HM), and the action of non-coding RNAs [6] [7]. These mechanisms alter gene expression without changing the underlying DNA sequence. During stress, these modifications can create a "memory" that allows the plant to respond more efficiently if the stress reoccurs. Some of these changes can even be stable and passed on to subsequent generations, a phenomenon known as transgenerational inheritance [6].

Q2: Can you provide a specific example of a gene regulated by epigenetic stress memory? A classic example is the Flowering Locus C (FLC) gene in Arabidopsis thaliana, which is regulated during cold stress through a process called vernalization [8]. Exposure to prolonged cold leads to the silencing of the FLC gene via histone modifications (specifically, the addition of repressive H3K27me3 marks). This epigenetic silencing "memorizes" the cold exposure and prevents flowering until after winter has passed, ensuring the plant flowers in the favorable conditions of spring [8].

Q3: What techniques are essential for studying epigenetic stress memory in plants? Advanced genome-wide profiling technologies are crucial. The field relies heavily on next-generation sequencing to map epigenetic marks across the entire genome [6]. Key methodologies include:

- Bisulfite Sequencing: For profiling DNA methylation patterns.

- Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing (ChIP-seq): For identifying histone modifications and transcription factor binding sites.

- RNA-seq: For analyzing the expression of non-coding RNAs and stress-responsive genes.

Q4: My experiment shows high variation in stress memory between plant individuals. What could be the cause? Biological variation in plant stress response studies can arise from several factors:

- Genotype-Specific Responses: Different plant species and even cultivars within a species have unique genetic makeups that influence how they perceive and epigenetically encode stress [6].

- Stressor Characteristics: The type, intensity, and duration of the stress itself can lead to different epigenetic outcomes [6] [9].

- Tissue Specificity: Epigenetic modifications are often tissue-specific. For example, a study on rice under salt stress found significant changes in DNA methylation in roots but only minor changes in leaves [6].

- Stochastic Events: Some epigenetic changes can occur randomly, contributing to variation within a genetically uniform population.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Problem: Inconsistent Stress Memory Phenotypes

Issue: Plants of the same genotype show inconsistent or weak memory responses upon secondary stress exposure.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Approach | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient priming stress | Review literature for established stress intensity/duration for your plant species. | Optimize and strictly standardize the primary stress protocol to ensure it is strong enough to establish a memory. |

| Variable environmental conditions | Monitor and log growth chamber conditions (light, temperature, humidity) throughout the experiment. | Ensure consistent environmental conditions for all plant groups to minimize uncontrolled variables. |

| Inadequate rest period | Test different recovery periods between primary and secondary stress application. | Implement a defined and appropriate recovery period to allow for the establishment of stable epigenetic marks. |

Problem: High Technical Variation in Epigenetic Data

Issue: High variability in results from techniques like bisulfite sequencing or ChIP-seq.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Approach | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Non-uniform tissue sampling | Check the consistency of tissue dissection and collection protocols. | Precisely define and consistently harvest the same tissue type and developmental stage from all biological replicates. |

| Issues with reagent quality | Use positive controls and quality control metrics (e.g., Bioanalyzer profiles for DNA/RNA). | Use high-quality, validated reagents and kits. Aliquot reagents to avoid freeze-thaw cycles. |

| Low sample purity | Check sample purity using spectrophotometry (e.g., Nanodrop). | Follow optimized nucleic acid or chromatin extraction protocols and include purification steps as necessary. |

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing DNA Methylation Changes in Response to Abiotic Stress

This protocol outlines a method to identify changes in DNA methylation patterns in plants following stress exposure.

1. Plant Material and Stress Application:

- Use genetically uniform plant material (e.g., inbred lines).

- Apply a defined and controlled stress (e.g., salinity, drought, heat) to the treatment group, while maintaining a control group under optimal conditions.

- After the stress period, allow for a recovery period to distinguish transient from stable methylation changes.

2. DNA Extraction and Bisulfite Conversion:

- Harvest plant tissue (e.g., leaves, roots) and isolate high-quality genomic DNA.

- Treat the DNA with sodium bisulfite. This process converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils, while methylated cytosines remain unchanged.

3. Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS):

- Prepare a sequencing library from the bisulfite-converted DNA.

- Perform high-throughput sequencing to cover the genome at a high depth.

- Map the sequenced reads to a reference genome and quantify methylation levels at each cytosine position (in CG, CHG, and CHH contexts).

4. Data Analysis:

- Identify Differentially Methylated Regions (DMRs) by comparing the treatment and control groups.

- Correlate DMRs with changes in gene expression data (e.g., from RNA-seq) to link methylation changes to functional outcomes.

Protocol 2: Investigating Histone Modifications in Stress Memory

This protocol describes how to profile histone modifications associated with stress memory genes.

1. Stress Priming and Challenge:

- Subject plants to a primary stress to establish memory.

- After a recovery period, apply a secondary, similar stress to trigger the memorized response.

2. Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP):

- Cross-link proteins to DNA in harvested plant tissue.

- Isolate and shear the chromatin to fragment DNA.

- Immunoprecipitate the protein-DNA complexes using antibodies specific to the histone modification of interest (e.g., H3K4me3 for active marks, H3K27me3 for repressive marks).

3. ChIP Sequencing (ChIP-seq):

- Reverse the cross-links and purify the DNA.

- Construct a sequencing library from the immunoprecipitated DNA and sequence it.

- Align sequences to the reference genome to identify genomic regions enriched for the specific histone mark.

4. Data Integration:

- Compare ChIP-seq profiles from primed and non-primed plants to identify memory-specific epigenetic changes at key stress-responsive genes, such as heat shock factors (e.g., HSFA2) or flowering regulators (e.g., FLC) [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Reagent / Material | Function in Epigenetic Stress Research |

|---|---|

| Sodium Bisulfite | Critical chemical for bisulfite sequencing; converts unmethylated cytosine to uracil to distinguish methylated bases [6]. |

| Histone Modification-Specific Antibodies | Used in ChIP experiments to pull down chromatin fragments with specific histone marks (e.g., H3K4me3, H3K27me3) [8]. |

| DNA Methyltransferases/Demethylase Mutants | Genetic tools (e.g., drm2 mutants) to study the function of specific enzymes in establishing or erasing DNA methylation in response to stress [6]. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing Kits | For preparing libraries for Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS), ChIP-seq, and RNA-seq to generate genome-wide epigenetic and transcriptional data [6]. |

| Polycomb Repressive Complex (PRC) Mutants | Used to study the role of PRC1 and PRC2 in maintaining repressive histone marks and stable gene silencing during stress memory, such as in vernalization [8]. |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Diagram: Simplified Cold Stress Memory via Vernalization

Diagram: Experimental Workflow for Profiling Stress Memory

Theoretical Foundation: Understanding the Growth-Defense Trade-Off

What is the growth-defense trade-off in plants?

The growth-defense trade-off describes a fundamental physiological compromise in plants, where limited cellular resources are allocated either to growth processes or to stress defense mechanisms. Since plants are sessile organisms unable to escape adverse conditions, they have evolved sophisticated signaling networks that dynamically prioritize between these competing demands. When plants perceive environmental stress, they actively suppress growth and redirect energy toward defense activation, which is beneficial for survival but often undesirable for agricultural productivity where yield is prioritized [10] [11].

This balance is regulated by a complex interplay of hormonal signaling pathways, with jasmonates (JAs), abscisic acid (ABA), and gibberellins (GAs) playing particularly important roles. Research has demonstrated that under stress conditions such as mechanical touch, plants exhibit significant growth reduction while simultaneously increasing resistance to herbivory, illustrating the operational trade-off in action [11].

What molecular mechanisms govern this balance?

The molecular control of growth-defense balance involves coordinated action across multiple signaling pathways and regulatory proteins:

Key Regulatory Components:

- Phytohormone Crosstalk: JA, ABA, and GA pathways interact antagonistically and synergistically to fine-tune the balance [11] [12]. For instance, OPDA (a JA precursor) coordinates growth reduction in response to touch stress, while JA itself regulates induced defenses [11].

- DELLA Proteins: These growth repressors in the GA pathway accumulate under stress and promote survival by delaying cell death through enhanced ROS scavenging [13].

- Energy-Sensing Kinases: SnRK1 and TOR kinases act antagonistically; SnRK1 activates catabolism and represses growth under low-energy stress conditions, while TOR promotes growth when resources are abundant [13].

- Transcription Factors: Families including ERF, bZIP, WRKY, MYB, and NAC integrate stress signals to regulate downstream gene expression, directing resources toward defense or growth programs [14].

Table 1: Major Transcription Factor Families in Growth-Defense Balance

| TF Family | Key Regulators | Stress Responsiveness | Primary Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| ERF | ERF2, ERF8 | Drought, cold, pathogens, wounding, JA/ET signaling [14] | Activates or represses defense genes; enhances stress tolerance when overexpressed [14] |

| bZIP | ABF1, ABF2 | Drought, salinity, temperature extremes [14] | Regulates ABA-dependent signaling; controls stomatal closure and water conservation [12] |

| WRKY | WRKY2, WRKY6, WRKY18 | Pathogens, wounding, drought, salinity, oxidative stress [14] | Modulates defense gene expression; integrates biotic and abiotic stress signaling [14] |

| NAC | Multiple members | Drought, salinity, cold [14] | Plant-specific TFs with roles in development and abiotic stress tolerance [14] |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

How can researchers account for biological variation in drought stress experiments?

Biological variation presents significant challenges in drought stress studies. To ensure reproducible and meaningful results:

- Standardize Stress Application: Clearly define and maintain consistent drought conditions across experiments. The severity, duration, and number of stress exposures must be precisely controlled and documented [15] [13].

- Consider Developmental Stage: Plant responses to drought vary significantly across growth stages. Always document the developmental stage and use uniform plant materials to reduce variability [15].

- Account for Organ-Specific Responses: Roots and shoots perceive and respond to drought differently. Analyze responses in specific tissues separately rather than using whole-plant extracts to obtain more precise data [13].

- Monitor Multiple Parameters: Combine physiological measurements (stomatal conductance, photosynthetic rate, Fv/Fm) with molecular analyses to capture comprehensive response profiles and account for variation between different response systems [15] [16].

What controls are essential for reliable growth-defense trade-off experiments?

- Positive Controls: Include genotypes with known stress response phenotypes (e.g., constitutive defense activation mutants) to verify your stress treatments are effective [11].

- Negative Controls: Utilize mutants deficient in key signaling pathways (e.g., JA biosynthesis mutants) to confirm the specificity of your observed responses [11].

- Temporal Controls: Collect samples at multiple time points during stress application and recovery, as the trade-off is dynamically regulated rather than static [16].

- Environmental Controls: Carefully regulate growth chamber conditions, as slight variations in light, temperature, and humidity can significantly alter trade-off responses [15].

Why might expected molecular markers not appear in stress experiments?

- Insufficient Stress Severity/Duration: The stress application may not have reached the threshold required to activate defense programs while inhibiting growth. Conduct pilot studies to establish appropriate stress intensity [15].

- Inappropriate Sampling Time: Molecular markers have distinct temporal expression patterns. If samples are collected too early or late in the stress response, key markers may be missed [16].

- Compensatory Mechanisms: Genetic redundancy or parallel signaling pathways may compensate for manipulated genes, masking expected phenotypes [11].

- Organ-Specific Expression: Your marker of interest might be expressed only in certain tissues or cell types not included in your sampling [13].

Experimental Protocols for Studying Growth-Defense Balance

Protocol: Analyzing Molecular Responses to Abiotic Stress

This protocol provides a framework for investigating transcriptomic and metabolomic changes during stress exposure [14] [16]:

Materials Required:

- Plant materials (wild-type and mutant genotypes)

- Stress application equipment (growth chambers, drought facilities)

- RNA extraction kit (e.g., TRIzol-based methods)

- cDNA synthesis kit

- qPCR system and reagents

- LC-MS/MS system for metabolomics

- Standard laboratory equipment (centrifuges, nanodrop spectrophotometer, thermal cycler)

Procedure:

- Plant Growth & Stress Application:

- Grow plants under controlled conditions to appropriate developmental stage.

- Apply standardized stress treatment (drought, salinity, cold, etc.) with precise documentation of severity and duration [15].

- Include unstressed control plants grown in parallel.

Sample Collection:

- Harvest tissue samples at multiple time points (during initial alarm phase, acclimation phase, and recovery).

- Immediately flash-freeze in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C.

- Note: Collect replicates (biological and technical) to account for variation.

RNA Extraction & Quality Control:

- Extract total RNA using standard methods.

- Verify RNA quality and integrity (A260/A280 ratio ~2.0, clear ribosomal bands on gel).

- Treat with DNase to remove genomic DNA contamination.

Reverse Transcription & qPCR:

- Synthesize cDNA using reverse transcriptase.

- Perform qPCR with primers for stress-responsive genes (Table 2) and reference genes.

- Use appropriate statistical methods (e.g., 2^-ΔΔCt) for analysis.

Metabolite Profiling:

- Extract metabolites using appropriate solvents (e.g., methanol:water mixtures).

- Analyze using LC-MS/MS with appropriate standards.

- Identify stress-responsive metabolites using computational pipelines.

Table 2: Key Molecular Markers for Different Stress Types

| Stress Type | Early Signaling Components | Transcription Factors | Metabolic Markers | Physiological Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drought | ABA, ROS, Ca2+ [12] | DREB, AREB/ABF, MYC/MYB [12] | Proline, sugars [12] | Stomatal closure, growth suppression [10] |

| Cold | Ca2+, CDPKs [12] | DREB1A, SCOF-1, CBF [12] | Soluble sugars, antifreeze proteins [12] | Membrane lipid remodeling, photosynthetic adjustment [12] |

| High Salinity | JA, ABA, Ca2+ [12] | DREB/CBF, bZIP, SOS pathway [12] | Compatible solutes, polyamines [12] | Ion homeostasis, ROS scavenging [12] |

| Biotic Stress | SA, JA, ROS [14] | WRKY, ERF, NPR1 [14] | Phytoalexins, glucosinolates [17] | Defense compound production, hypersensitive response [14] |

Protocol: Assessing Trade-Offs Through Physiological Measurements

Materials Required:

- Photosynthesis measurement system (IRGA)

- Chlorophyll fluorescence imaging system

- Root phenotyping system

- Precision balances

- Plant growth analysis software

Procedure:

- Pre-Stress Baseline Measurements:

- Record initial plant weight, height, leaf area, and root architecture.

- Measure baseline photosynthetic parameters (A, gs, Fv/Fm).

- Document developmental stage.

Stress Application & Monitoring:

- Apply controlled stress while monitoring environmental conditions.

- Track physiological parameters at regular intervals.

- Document visible symptoms and morphological changes.

Growth-Defense Quantification:

- Compare growth rates (biomass accumulation, leaf expansion) between stressed and control plants.

- Measure defense activation (antioxidant capacity, defense compound production, pathogen/herbivore resistance).

- Calculate trade-off magnitude as the ratio between growth reduction and defense enhancement.

Data Analysis:

- Use statistical models to correlate molecular changes with physiological responses.

- Apply dimension reduction techniques (PCA) to identify key response traits.

- Construct response networks integrating molecular and physiological data.

Visualization of Key Signaling Pathways

Drought Stress Signaling Pathway

JA-GA Crosstalk in Growth-Defense Balance

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Plant Stress Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Biology Kits | RNA extraction kits, cDNA synthesis kits, qPCR master mixes | Gene expression analysis of stress markers [14] [16] | Quantify transcript levels of key regulatory genes |

| Antibodies & Immunoassays | ABA ELISA kits, HSP antibodies, pathogen detection assays | Hormone quantification, pathogen detection, protein localization [16] | Detect and quantify stress-related molecules and pathogens |

| Chemical Inhibitors/Agonists | JA biosynthesis inhibitors, GA biosynthesis inhibitors, kinase inhibitors | Pathway dissection through pharmacological approaches [11] | Test necessity/sufficiency of specific pathway components |

| Genetically Modified Lines | JA-deficient mutants, DELLA mutants, TF overexpression lines | Functional testing of specific genes [11] [13] | Establish causal relationships between genes and phenotypes |

| Metabolomics Standards | Phytohormone standards, antioxidant standards, LC-MS metabolite standards | Metabolite profiling and identification [17] [16] | Identify and quantify stress-responsive metabolites |

| Sensor Lines | Rationetric ROS sensors, Ca2+ sensors, fluorescent protein reporters | Real-time monitoring of signaling events [16] | Visualize spatial and temporal dynamics of stress responses |

Advanced Methodologies: Integrating Multi-Omic Approaches

How can researchers integrate multiple technologies to comprehensively study stress responses?

Given the complexity of growth-defense trade-offs, a single-method approach often provides incomplete understanding. Integrated multi-omic strategies are essential for capturing the full spectrum of plant stress responses [16]:

Recommended Integrated Workflow:

- Genomics/Transcriptomics: Identify candidate genes and expression patterns through RNA-seq and gene expression profiling [14] [16].

- Proteomics: Validate protein-level changes and post-translational modifications using MS-based approaches [14] [16].

- Metabolomics: Profile stress-responsive metabolites and defense compounds through LC-MS and GC-MS [17] [16].

- Ionomics: Analyze elemental composition and nutrient dynamics under stress [16].

- Phenomics: Quantify physiological and morphological responses through automated imaging and sensor technologies [16].

This integrated approach enables researchers to connect molecular changes with physiological outcomes, providing a systems-level understanding of how plants balance growth and defense under stress [16].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why do I observe high variability in systemic immune responses between individual plants in my experiments? High variability can often be attributed to the dynamic nature of root microbiome composition and the "standby mode" of immune signaling. Research shows that roots maintain basal levels of the immune signal N-hydroxypipecolic acid (NHP) in an inactivated, conjugated form. The sensitivity of this system means that slight differences in microbial exposure or plant metabolic state can lead to varied activation and transport of free NHP to shoots, resulting in differential immune priming [18].

Q2: How can I better control for the microbiome's influence when studying root-shoot signaling? Utilize gnotobiotic plant systems with defined Synthetic Microbial Communities (SynComs). Studies successfully employ SynComs of specific bacteria, fungi, and oomycetes to standardize the root microbiome. This approach demonstrated that a defined microbiota could rescue Arabidopsis growth under suboptimal light, an effect that required specific host factors like the transcription factor MYC2 [19]. This method reduces uncontrolled biological variation from soil microbes.

Q3: What could cause inconsistent shoot growth responses after manipulating root nutrient sensing pathways? Inconsistent growth may stem from crosstalk between different systemic signaling pathways. For instance, nutrient signaling is finely tuned by opposing pathways. The CEP (C-terminally encoded peptides) pathway signals nitrogen deficiency from roots to shoots, while the trans-zeatin (tZ) pathway signals nitrogen sufficiency. Simultaneous activation of these pathways, due to heterogeneous soil conditions or internal plant status, can lead to conflicting growth outputs [20]. Ensuring uniform nutrient availability, for example using split-root systems, can mitigate this.

Q4: My measurements of systemic defense signals don't correlate with pathogen resistance. What might be wrong? This discrepancy can arise from the growth-defense trade-off dictated by the microbiota-root-shoot circuit. Under suboptimal conditions like low light, the presence of a root microbiome can prioritize growth over defense, leading to reduced defense responses even when systemic signals are present. This trade-off is directly linked to belowground bacterial community composition and requires the host's MYC2 transcription factor [19]. Consistently control environmental conditions and characterize the microbial community to interpret defense signaling accurately.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Erratic Lateral Root Development in Nitrogen Signaling Studies

Potential Cause: Non-specific activation of compensatory root development due to uneven nitrogen distribution or concurrent activation of multiple signaling peptides.

Solution:

- Standardize Growth Substrate: Use a homogenous growth medium. For localized nitrogen application, employ a split-root system where the root system is physically divided between high-N and low-N compartments [20].

- Monitor Key Signals: Track the expression of CEP genes in roots and the movement of CEPD/CEPDL2 peptides from shoots to roots, as these are central to the systemic N-demand signaling [20].

- Genetic Controls: Use mutants in key signaling components (e.g.,

cepr,cepdmutants) to confirm the specificity of the observed root phenotype [20].

Problem: Lack of Expected Systemic Immune Priming After Root Pathogen Challenge

Potential Cause: Disruption in the synthesis, conjugation, or transport of the root-to-shoot signal N-hydroxypipecolic acid (NHP).

Solution:

- Verify Signal Inactivation Mechanism: Check the status of NHP conjugation. The basal NHP in roots is typically inactivated by glucose conjugation; microbial interaction should trigger its deconjugation and release [18].

- Quantify Long-Distance Signal: Directly measure levels of free NHP in the xylem sap or in shoot tissues following root inoculation, rather than relying solely on gene expression markers in roots [18].

- Control Microbiome: Ensure that the experimental plants have a consistent and defined microbial background, as the standing microbial community can pre-condition the immune system state [19].

Key Signaling Pathways: Data and Protocols

Table 1: Systemic Signaling Molecules in Root-Shoot Communication

| Signaling Molecule | Origin | Target Tissue | Function | Key Regulatory Proteins |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N-hydroxypipecolic acid (NHP) [18] | Roots | Shoots | Immune priming; systemic acquired resistance | Biosynthesis enzymes (e.g., AOP3); conjugation enzymes |

| C-terminally encoded peptides (CEPs) [20] | N-deficient Roots | Shoot Vasculature | Induce expression of nitrate transporters | CEP Receptor (CEPR) in shoots |

| CEPD/CEPDL2 Polypeptides [20] | Shoot Vasculature | Roots | Upregulate NRT2.1 expression to enhance nitrate uptake |

CEPR in shoots |

| trans-Zeatin (tZ) [20] | N-sufficient Roots | Shoots | Signal nitrogen sufficiency; suppress foraging | Cytokinin receptors |

| HY5 Transcription Factor [20] | Shoots (synthesized) | Roots (mobile) | Integrates light and nutrient signaling; promotes nitrate uptake & root growth | - |

Table 2: Common Stressors and Their Systemic Signaling Components

| Stress Type | Sensor/Initial Signal | Systemic Signal | Measurable Physiological Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen Deficiency [20] | Local nitrate availability | CEP peptides → CEPDL2 | Increased lateral root growth; upregulation of NRT2.1 |

| Phosphate Deficiency [20] | Local phosphate availability | (Under review) miRNAs, hormones | Altered root architecture; exudation of organic acids |

| Root Pathogen Attack [18] | Microbial-associated molecular patterns | N-hydroxypipecolic acid (NHP) | Induced defense gene expression in shoots; growth inhibition |

| Suboptimal Light [19] | Leaf photoreceptors | Altered carbon metabolites | Modulation of root bacterial community; growth-defense trade-off |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Establishing a Split-Root System to Study Systemic Nutrient Signaling

Purpose: To physically separate a root system into distinct compartments, allowing researchers to expose different parts of the root system to different conditions and study long-distance signaling [20].

Materials:

- Plant seedlings (e.g., Arabidopsis, tomato)

- Agar or hydroponic media

- Split-root containers or partitioned plates

- Nutrient solutions (e.g., +N, -N)

Methodology:

- Germination: Germinate seeds on a sterile, vertical agar plate.

- Root Tip Division: Once the primary root is 2-3 cm long, carefully excise the root tip (approx. 2-3 mm) to break apical dominance and induce the growth of two or more lateral roots of similar length.

- Transfer to System: Transfer the seedling to a split-root system where the two lateral roots are guided into separate compartments.

- Application of Treatments: After the roots have established in both compartments (typically 5-7 days), apply the experimental treatment (e.g., -N solution) to one compartment and the control (e.g., +N solution) to the other.

- Analysis: Harvest root and shoot tissues from each compartment separately for molecular (gene expression, metabolite analysis) and phenotypic (lateral root counting, biomass measurement) analysis.

Protocol 2: Profiling Root Microbiome Using Gnotobiotic Systems and SynComs

Purpose: To control and manipulate the plant microbiome, reducing variability and enabling functional studies of specific microbes in root-shoot communication [19].

Materials:

- Sterile plant seeds

- Gnotobiotic growth systems (e.g., FlowPot)

- Culture collections of root-associated bacteria, fungi, and oomycetes

- DNA/RNA extraction kits

- Sequencing facilities (16S rRNA, ITS)

Methodology:

- Surface Sterilization: Surface-sterilize plant seeds and germinate them on sterile media.

- SynCom Preparation: Grow individual microbial strains to the logarithmic phase. Combine them at defined relative abundances to create a Synthetic Community (SynCom).

- Inoculation: Transfer germ-free seedlings to the gnotobiotic system and inoculate the roots with the SynCom.

- Application of Abiotic Stress: Apply the desired abiotic stress (e.g., low photosynthetically active radiation) to the shoots.

- Sample Collection and Sequencing: After a set period, collect root and rhizosphere samples. Extract total DNA and perform amplicon sequencing (16S for bacteria, ITS for fungi/oomycetes) to profile the microbial community.

- Phenotyping: In parallel, measure plant phenotypes such as shoot fresh weight, leaf area, and defense marker gene expression.

Signaling Pathway Diagrams

Root-to-Shoot Systemic Immune Signaling

Systemic Nitrogen Signaling Circuit

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying Systemic Signaling

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Microbial Communities (SynComs) [19] | Defined consortia of microbes to standardize the root microbiome and study its function. | Investigating the role of specific bacterial strains in rescuing plant growth under low light [19]. |

| Gnotobiotic Plant Systems [19] | Sterile growth environments (e.g., FlowPot) that allow inoculation with known microbes. | Maintaining axenic conditions or plants with defined microbiomes for reproducible root-shoot studies [19]. |

| Split-Root Systems [20] | Physical separation of a root system to apply localized treatments. | Studying systemic N signaling by exposing one part of the root to low N and another to high N [20]. |

| Mutant Lines (e.g., myc2, cepr, nhp biosynthesis) [19] [20] [18] | Genetic tools to dissect the function of specific genes in signaling pathways. | Confirming the essential role of MYC2 in the microbiota-mediated growth-defense trade-off [19]. |

| Mass Spectrometry [18] | Quantitative measurement of signaling molecules (e.g., NHP, CEP peptides, hormones). | Directly quantifying the flux of NHP from roots to shoots upon immune challenge [18]. |

FAQ: Understanding Temporal Dynamics in Plant Stress

What are the key phases of a plant's temporal response to stress?

The response to a sudden stressor, such as high salinity, is not a single event but a multi-phasic process. Research on Arabidopsis thaliana roots shows this unfolds in distinct phases: an initial stop phase (hours 1-4 post-stress) where growth rates fall dramatically, a period of maintained slow growth (~4 hours), followed by a recovery phase where growth gradually resumes before reaching a new state of homeostasis [21].

Why is understanding temporal dynamics critical for my experiments?

Ignoring time-course data can lead to incomplete or misleading conclusions. The molecular events during the initial shock phase are fundamentally different from those during acclimation [21]. For example, the hormone ABA acts in a tissue-specific manner to regulate growth recovery; if you only measure endpoints, you will miss these critical, spatially-patterned regulatory events [21]. Furthermore, transcriptomic responses are highly dynamic, and sampling at a single time point will capture only a fraction of the relevant biological story [22].

How can I manage biological variation in time-course experiments?

Biological variation is a major challenge when studying dynamic processes. Key strategies include:

- High-Resolution Sampling: Do not rely on sparse time points. The use of live-imaging, for instance, allows for continuous, non-invasive monitoring of growth parameters, capturing subtle transitions that would be missed with end-point measurements [21].

- Tissue-Specific Resolution: Bulk analysis of whole organs can mask critical tissue-specific responses. Techniques like Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) of protoplasted tissues expressing cell-specific fluorescent markers enable high-resolution spatio-temporal transcriptional mapping [21].

- Replication and Controls: Ensure sufficient biological replication at each time point and include matched controls to distinguish stress-specific responses from general developmental changes.

Troubleshooting Guide for Common Experimental Challenges

| Issue | Diagnosis | Solution | Underlying Principle |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent stress response phenotypes | Biological variation is obscuring the dynamic response pattern. Single time-point measurements are missing key transitions. | Implement live-imaging and high-resolution, multi-time-point sampling (e.g., 1h, 2h, 4h, 8h, 24h, 48h). Use tissue-specific reporters to dissect spatial contributions [21]. | Stress acclimation is a phasic process. Growth and molecular changes are temporally and spatially regulated [21]. |

| Unclear signaling pathway hierarchy | The roles of specific hormones (e.g., ABA, ethylene) appear context-dependent and change over time. | Employ a bioinformatic approach to link time-course transcriptomic data with public hormone response datasets. Validate predictions using tissue-specific suppression of signaling pathways [21]. | Hormone signaling pathways interact in a complex network, with their activity and dominance shifting between phases of the stress response [21] [23]. |

| Poor stress recovery in mutants | A mutant may not be defective in the initial stress sensing, but rather in the mechanisms that enable recovery and growth acclimation. | Use live-imaging to precisely quantify the duration of the stop phase and the rate of growth recovery. Analyze gene expression related to ion homeostasis and osmolyte synthesis during the recovery phase [21] [23]. | Recovery involves active processes like ion transporter activation (e.g., SOS pathway) and synthesis of compatible osmolytes (e.g., proline), not just the cessation of the initial stress signal [21] [23]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Assays

Live-Imaging for Quantifying Dynamic Growth

This protocol is adapted from studies on Arabidopsis root growth under salt stress [21].

Objective: To non-invasively monitor and quantify the dynamic changes in root growth rate before, during, and after the application of an abiotic stress.

Materials:

- Custom live-imaging system with computer-controlled stage and transmitted infrared light.

- Vertical growth plates containing agar medium.

- Semiautomated image analysis software (e.g., as described in Duan et al., 2013).

Method:

- Preparation: Grow Arabidopsis seedlings vertically on the surface of agar in tissue culture plates for 5 days under standard conditions.

- Baseline Imaging: Place plates on the imaging system and capture images every 15 minutes for a 24-hour period to establish baseline growth rates.

- Stress Application: Transfer plates to fresh medium supplemented with the stressor (e.g., 140 mM NaCl) or to control medium. The transfer process itself can cause a slight growth suppression, making a control transfer essential.

- Post-Stress Imaging: Continue time-lapse imaging every 15 minutes for at least 48-72 hours post-stress.

- Data Analysis: Use semiautomated software to track root tip position and calculate elongation rates over time, independent of root tip waving. Plot growth rate versus time to visualize the stop, maintenance, recovery, and homeostasis phases.

High-Resolution Spatio-Temporal Transcriptomics

Objective: To generate a tissue-specific, multi-time point transcriptional map of the stress response.

Materials:

- Transgenic plant lines expressing GFP under tissue-specific promoters.

- Protoplasting enzymes.

- Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorter (FACS).

- RNA-seq library preparation and sequencing platforms.

Method:

- Stress Treatment & Sampling: Expose plants to stress and collect root samples at multiple time points (e.g., 1, 2, 4, 8, 24, 48 hours) along with matched controls.

- Tissue Dissociation: Protoplast the roots using a brief enzymatic treatment to create a single-cell suspension.

- Cell Sorting: Use FACS to isolate GFP-positive cells from specific tissue layers (e.g., epidermis, cortex, stele).

- RNA Sequencing: Isulate total RNA from each sorted cell population and construct RNA-seq libraries. Sequence using a high-throughput platform (e.g., Illumina).

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Identify Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) for each tissue and time point. Use clustering and pathway analysis to identify temporal and spatial expression trends. Integrate with public datasets on hormone responses to predict regulating pathways [21].

Visualizing Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Salt Stress Signaling Pathway

This diagram summarizes key molecular events in the response to salt stress, from initial sensing to acclimation.

Experimental Workflow for Temporal Analysis

This diagram outlines a logical workflow for designing an experiment to analyze the temporal dynamics of a plant stress response.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function in Stress Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Protein Reporters | Visualize gene expression and protein localization in specific cell types in real time. | Generating tissue-specific GFP lines for FACS isolation and live-imaging of stress-responsive promoters [21]. |

| OSCA Ion Channels | Mediate hyperosmolarity-induced calcium influx; function as osmotic stress sensors [23]. | Studying early signaling events in osmotic stress using mutant lines. |

| SOS Pathway Components (SOS1, SOS2, SOS3) | Key signaling module for ion homeostasis under salt stress; SOS1 is a Na+/H+ antiporter [23]. | Analyzing Na+ flux and compartmentalization in sos mutant backgrounds. |

| SnRK2 Protein Kinases | Central regulators activated by osmotic stress; key players in ABA-dependent and independent signaling [23]. | Investigating phosphorylation events in signal transduction cascades. |

| Heat Shock Proteins (HSPs) | Act as molecular chaperones to prevent protein denaturation and maintain proteostasis under heat and other stresses [23]. | Quantifying thermotolerance and protein aggregation in different genotypes. |

| Dendrometers / Trunk Displacement Sensors | Measure minute changes in trunk diameter, providing a continuous, physical readout of plant water status and stress [24]. | Monitoring water-related stress in trees or large plants in field or greenhouse settings. |

| FACS (Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorter) | Isolate specific cell types from protoplasted tissues based on fluorescent markers for high-resolution omics studies [21]. | Obtaining pure populations of root stele or epidermal cells for transcriptomic profiling. |

Advanced Tools and Techniques: Capturing Complex Variation Across Biological Scales

In plant stress response studies, biological variation presents a significant challenge, as plants exhibit complex, dynamic molecular changes when facing abiotic stressors like drought, heat, and waterlogging [25] [26]. Multi-omics data integration has emerged as a powerful approach to overcome this challenge by harmonizing multiple layers of biological data—including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—to provide a more comprehensive understanding of physiological and biochemical processes [27] [26]. This methodology reduces the limitations and biases associated with single-omics approaches by enabling cross-validation and integration of multiple data types, thereby revealing molecular relationships not detectable when analyzing each omics layer in isolation [27]. For researchers and drug development professionals, multi-omics integration provides unprecedented insights into disease mechanisms, identifies molecular biomarkers and novel drug targets, and aids the development of precision medicine approaches [27].

Key Challenges in Multi-Omics Integration

Technical and Analytical Bottlenecks

Integrating multi-omics data presents significant bioinformatics and statistical challenges that can stall discovery efforts, especially for those without computational expertise [27]. These challenges include:

- Heterogeneous Data Structures: Each omics data type has unique data structure, distribution, measurement error, and batch effects [27]. For example, transcriptomics may profile thousands of genes, while proteomic methods often have a more limited spectrum, potentially detecting only 100 proteins [28].

- Lack of Preprocessing Standards: The absence of standardized preprocessing protocols means tailored pipelines are often adopted for each data type, potentially introducing additional variability across datasets [27].

- Specialized Bioinformatics Expertise Required: Handling and analyzing large, heterogeneous data matrices requires cross-disciplinary expertise in biostatistics, machine learning, programming, and biology [27].

Method Selection and Interpretation Challenges

- Difficult Choice of Integration Method: Numerous integration algorithms exist, each with different approaches and applications, creating confusion about which method is best suited for a particular dataset or biological question [27].

- Challenging Biological Interpretation: Translating integration outputs into actionable biological insight remains difficult due to model complexity, missing data, and limited functional annotation [27].

Table 1: Common Multi-Omics Integration Challenges and Their Impacts on Research

| Challenge Category | Specific Issue | Impact on Research |

|---|---|---|

| Technical & Analytical | Heterogeneous data structures & noise profiles | Misleading conclusions without careful preprocessing |

| Data Quality | Missing data across modalities (e.g., gene visible at RNA level but absent at protein level) | Incomplete molecular profiles and difficult cross-modality comparisons |

| Method Selection | Multiple algorithms with different approaches (MOFA, DIABLO, SNF, etc.) | Confusion about optimal method for specific biological questions |

| Interpretation | Complex model outputs with limited functional annotation | Difficulty translating results into actionable biological insight |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

FAQ: What are the critical steps for ensuring quality in multi-omics data preprocessing?

Effective preprocessing requires both technical and biological considerations. From a technical perspective, specific quality control measures must be implemented for each omics layer. For transcriptomics, this includes adapter trimming with tools like Trimmomatic, quality filtering (e.g., removing reads with >10% N or >50% bases with Q≤20), and alignment to reference genomes using HISAT2, aiming for >80% mapping efficiency [29]. Biologically, researchers must account for tissue-specific responses, as different plant tissues can exhibit dramatically different molecular signatures under stress conditions [29].

FAQ: How do I handle missing data across different omics modalities?

Missing data is a common challenge in multi-omics studies, particularly when a gene detected at the RNA level may be missing in the protein dataset [28]. Effective strategies include:

- Implementing imputation methods specific to each data type

- Using integration algorithms robust to missing data (e.g., MOFA+)

- Designing experiments with sufficient biological replicates to distinguish technical zeros from biological absences

Integration Methodology Selection

FAQ: How do I choose the most appropriate integration method for my plant stress study?

Method selection depends on your experimental design and research objectives. The table below compares major integration approaches:

Table 2: Multi-Omics Integration Methods: Comparative Analysis for Method Selection

| Method | Integration Type | Key Approach | Best For | Plant Study Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOFA+ [27] [28] | Unsupervised, matched | Bayesian factor analysis to infer latent factors | Exploring unknown sources of variation without prior hypotheses | Identifying novel stress-response pathways |

| DIABLO [27] | Supervised, matched | Multiblock sPLS-DA with phenotype guidance | Biomarker discovery and classification with known outcomes | Predicting stress-tolerant vs. sensitive genotypes |

| SNF [27] | Unsupervised, unmatched | Similarity network fusion of sample networks | Integrating data from different samples/studies | Combining public datasets for meta-analysis |

| MCIA [27] | Unsupervised, matched | Multivariate covariance optimization | Simultaneous analysis of multiple omics datasets | Time-series analysis of stress responses |

FAQ: What is the difference between matched and unmatched integration, and why does it matter?

The distinction between matched and unmatched integration is fundamental to experimental design and analysis choices:

Matched (Vertical) Integration: Data from different omics are acquired concurrently from the same set of samples [27] [28]. This approach keeps the biological context consistent, enabling more refined associations between often non-linear molecular modalities [27]. The cell or sample itself serves as the anchor for integration [28].

Unmatched (Diagonal) Integration: Data is generated from different, unpaired samples [27] [28]. This requires more complex computational approaches that project cells into a co-embedded space to find commonality between cells in the omics space, as the sample cannot be used as a direct anchor [28].

Biological Interpretation and Validation

FAQ: How can I effectively interpret multi-omics results in the context of plant stress biology?

Successful interpretation requires both computational and biological approaches:

- Perform pathway enrichment analysis (GO, KEGG) to identify biological processes significantly affected by stress conditions [29]

- Cross-reference results with existing knowledge of plant stress biology—for example, the known roles of ABA in drought response or ethylene in waterlogging tolerance [25] [29]

- Validate key findings through transgenic experiments, as demonstrated in a maize study where overexpression of ZmPsbS significantly boosted photosynthesis and energy-dependent quenching after high-light treatment [30]

FAQ: What strategies can help address the complexity of hormonal interactions in plant stress responses?

Plant hormone signaling forms intricate networks that coordinate developmental programs and adaptive responses [29]. Effective strategies include:

- Analyzing time-resolved multi-omics data to capture dynamic hormonal changes

- Employing integration methods that can identify coordinated patterns across omics layers

- Validating computational predictions through hormonal measurements and mutant analyses

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Comprehensive Multi-Omics Workflow for Plant Stress Studies

The following workflow diagram illustrates a robust experimental design for plant stress response studies, incorporating best practices from recent research:

Protocol: Integrated Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Analysis of Waterlogging Stress

This detailed protocol is adapted from a study on Magnolia sinostellata waterlogging responses [29]:

1. Plant Materials and Stress Treatment

- Obtain uniform one-year-old cutting seedlings and acclimate for 7 days in a controlled greenhouse (25 ± 1°C, 60% relative humidity, 14h light/10h dark cycle, 300 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹ PAR)

- Impose waterlogging stress by placing potted plants in tanks filled with dechlorinated tap water (pH 6.5 ± 0.2) to 10 cm above soil surface

- Collect roots, stems, and leaves at 0h, 6h, and 72h post-stress with three biological replicates per time point

2. Morphological and Anatomical Observations

- Wash roots with deionized water and photograph root morphology using a flatbed scanner (e.g., Epson Perfection V700 Photo)

- Fix root tips in formalin-acetic acid-alcohol (FAA) and stain using Saffron-O and Fast Green Stain Kit following manufacturer's protocol (Solarbio, Beijing)

- Observe cell morphology with an optical microscope (e.g., Olympus BX43) to document adaptations like hypertrophic lenticels, aerenchyma formation, and adventitious root development

3. Transcriptome Sequencing and Analysis

- Extract total RNA using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) and verify quality via agarose gel electrophoresis, NanoPhotometer spectrophotometry, and Bioanalyzer 2100

- Sequence qualified RNA samples on Illumina HiSeq-2000 platform

- Process raw reads using Trimmomatic v0.33 to remove adapters and low-quality reads (>10% N or >50% bases with Q≤20)

- Align clean reads to reference genome using HISAT2 (>80% mapping efficiency)

- Perform differential expression analysis with DESeq2 (adjusted p-value < 0.05, |log₂ fold change| >1)

- Conduct GO and KEGG enrichment analysis using GOseq and KOBAS software

4. Metabolomic Analysis

- Collect samples from the same biological replicates used for transcriptomics

- Perform metabolite extraction using appropriate solvents (e.g., methanol:water mixtures)

- Analyze using LC-MS/MS systems with both positive and negative ionization modes

- Identify significantly altered metabolites using multivariate statistics (PCA, OPLS-DA)

5. Integrated Analysis

- Correlate transcriptomic and metabolomic datasets using correlation networks

- Identify key regulatory pathways through KEGG pathway mapping

- Validate candidate genes through transgenic experiments or functional studies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Plant Multi-Omics Studies

| Category | Specific Reagent/Kit | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction | Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) | Total RNA isolation from plant tissues | RNA extraction for transcriptome sequencing [29] |

| RNA Quality Control | Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent) | Assessment of RNA integrity number (RIN) | Quality verification before RNA-seq [29] |

| Histological Staining | Saffron-O & Fast Green Stain Kit (Solarbio) | Tissue staining for anatomical observations | Visualizing aerenchyma formation in waterlogged roots [29] |

| Fixation Solution | Formalín-Acetic Acid-Alcohol (FAA) | Tissue preservation for morphological studies | Fixing root tips for microscopic examination [29] |

| Sequencing Platform | Illumina HiSeq-2000 | High-throughput RNA sequencing | Transcriptome profiling of stress-treated samples [29] |

| Alignment Software | HISAT2 | Mapping sequencing reads to reference genomes | Alignment of transcriptomic data with >80% efficiency [29] |

| Differential Expression | DESeq2 | Statistical analysis of gene expression changes | Identifying stress-responsive genes (padj < 0.05) [29] |

| Multi-Omics Integration | MOFA+ [27] [28] | Unsupervised factor analysis for integration | Identifying latent sources of variation across omics layers |

| Pathway Analysis | KOBAS with KEGG database | Functional enrichment of omics data | Mapping molecular changes to biological pathways [29] |

Signaling Pathways in Plant Stress Responses

The following diagram illustrates the complex hormonal signaling network that coordinates plant responses to abiotic stresses, based on integrated multi-omics findings:

This integrated signaling network demonstrates how multi-omics approaches reveal the complexity of plant stress responses. For example, research has shown that waterlogging stress triggers rapid ethylene accumulation, which serves as the primary hypoxia signal initiating downstream responses [29]. This ethylene signal interacts with multiple hormonal pathways, including auxin (which regulates adventitious root development through transport and signaling pathways) and jasmonic acid (which interestingly acts as a negative regulator in some species like Magnolia sinostellata, contrasting with its positive role in other plants) [29]. These hormonal interactions are further fine-tuned by ROS signaling, creating a complex but highly coordinated defense network [29].

The molecular responses captured through multi-omics integration typically include downregulation of photosynthesis at different molecular levels, accumulation of minor amino acids, and diverse stress-induced hormonal changes [25]. Key regulatory genes identified through these approaches—such as CKX (cytokinin dehydrogenase) and JAR1 (JA-Ile synthetase) in waterlogging tolerance, or PsbS in high-light stress—provide promising targets for genetic improvement of stress tolerance in crops [30] [29].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

FAQ: Why is my root segmentation from X-ray CT data poor, and how can I improve it?

- Problem: Low contrast between root segments and soil matrix in X-ray CT volumes leads to inaccurate root system architecture (RSA) quantification.

- Solution:

- Soil Medium: Use a uniform particle size, calcined clay growth medium to reduce the probability of visualizing non-root segments and improve contrast [31].

- Scanner Settings: Increase the X-ray tube voltage and current during CT scanning to enhance the root-to-soil contrast [31].

- Image Processing: Apply a 3-D median filter to reduce noise, followed by an edge detection algorithm to isolate root segments automatically. This fully automatic method can achieve a high detection rate for roots in samples [31].

- Validation: Manually validate a subset of images to confirm segmentation accuracy. In rice seedlings, this protocol detected 85-100% of radicle and crown roots [31].

FAQ: How do I minimize the impact of repeated CT scanning on plant growth during a 4-D study?

- Problem: Cumulative X-ray dose from repeated scanning for 4-D (3-D over time) phenotyping may impede plant growth and introduce experimental artifacts [31].

- Solution:

- Dose Assay: Conduct an X-ray dose assay on your plant species before the main experiment. For rice, a dose per scan of < 0.09 Gy was found not to impede growth [31].

- Optimized Protocol: Implement a high-throughput process flow that uses rapid scanning and reconstruction to minimize exposure time. One such protocol requires only 10 minutes for scanning and reconstruction, and 2 minutes for image processing [31].

- Growth Monitoring: Closely monitor control and scanned plants for any significant differences in standard growth metrics to confirm the chosen dose is non-detrimental.

FAQ: My physiological trait data (e.g., from thermal imaging) does not correlate with morphological stress symptoms. What could be wrong?

- Problem: Physiological responses often precede visible morphological changes. A perceived lack of correlation may stem from incorrect data acquisition timing or sensor configuration [32].

- Solution:

- Temporal Resolution: Increase the frequency of measurements. Physiological traits are highly dynamic; for example, stomatal closure (detected via thermal imaging) can occur within minutes of stress onset, while growth reduction may take days [32].

- Multi-Sensor Validation: Use multiple imaging sensors simultaneously to capture different aspects of the stress response. For instance, combine:

- Sensor Calibration: Ensure all sensors are properly calibrated according to manufacturer specifications. For thermal imaging, account for ambient temperature, humidity, and atmospheric radiation [32].

FAQ: How can I manage the large datasets generated by HTP platforms effectively?

- Problem: HTP technologies produce massive, multi-dimensional datasets that are difficult to store, process, and analyze [34] [33].

- Solution:

- Data Management Plan: Create a plan with complete and accurate metadata, deposit data into a primary repository, and ensure it is accessible to researchers [35].

- Machine Learning: Utilize machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) approaches for automated feature extraction, classification, and prediction. DL models, particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), are state-of-the-art for image-based tasks like classification and segmentation, bypassing the need for manual feature design [34].

- Computing Power: Employ high-performance computing (HPC) technology to reduce image processing time, which can be as low as 2 minutes per sample with adequate resources [31].

Standard Operating Procedures for Key HTP Protocols

Protocol: 3-D Root System Architecture Visualization Using X-Ray Computed Tomography

This protocol details a high-throughput method for non-destructive, 3-D visualization of root system architecture (RSA) in soil using X-ray CT, suitable for genetic analysis [31].

- Primary Application: Phenotyping RSA for responses to abiotic stresses like drought and nutrient deficiency.

- Key Equipment and Software:

- X-ray CT scanner (non-medical).

- Procedure:

- Plant Preparation:

- Grow plants in pots (e.g., 20 cm diameter, 25 cm depth) filled with a uniform, calcined clay growth medium to improve image contrast [31].

- CT Scanning:

- Use a higher tube voltage and current to increase root-to-soil contrast [31].

- Aim for a short scanning time (e.g., 10 minutes per sample) to enable high-throughput processing. The total elapsed time per sample, including machine operation, may be 15 minutes [31].

- Ensure the X-ray dose per scan is below the threshold that impedes plant growth (e.g., < 0.09 Gy for rice) for 4-D studies [31].

- Image Reconstruction:

- Use the scanner's software to reconstruct multi-angle projections into densitometric slice images, which are stacked to construct 3-D volumes [31].

- Root Segmentation (Fully Automatic):

- Trait Extraction:

- Use appropriate software to compute RSA traits from the segmented 3-D model, such as root depth, root angle, lateral root distribution, and total root volume.

- Plant Preparation:

The following workflow diagram summarizes the key steps of this protocol:

Protocol: Image-Based Phenotyping for Morpho-Physiological Responses to Combined Stresses

This protocol uses multiple imaging sensors to assess above-ground morphological and physiological responses to single and combined abiotic stresses in potato, but is adaptable to other crops [32].

- Primary Application: Quantifying dynamic plant responses to stress combinations (e.g., heat, drought, waterlogging) in controlled environments.

- Key Equipment and Software:

- RGB imaging sensor.

- Chlorophyll fluorescence imager.

- Thermal infrared (IR) camera.

- Hyperspectral imaging sensor.

- Automated phenotyping platform (optional but recommended).

- Procedure:

- Plant Preparation and Growth:

- Transplant plants into pots with a standardized soil mixture (e.g., 3:1 Klasmann Substrate 2:Sand) [32].

- Place blue mats on the pot surface to simplify the separation of plant pixels from the soil background during image segmentation [32].

- Maintain plants at a controlled soil relative water content (SRWC), e.g., 60% for controls, before stress imposition [32].

- Use a minimum of 10 biological replicates per treatment and randomize pots [32].

- Stress Application:

- At the desired developmental stage (e.g., onset of tuberization), impose stresses to defined levels:

- Multi-Sensor Imaging:

- Conduct imaging sessions at regular intervals (e.g., daily) during pre-stress, stress, and recovery phases.

- RGB Imaging: Capture top and side views to quantify projected leaf area, plant architecture, and biomass [32].

- Chlorophyll Fluorescence Imaging: Measure the quantum yield and efficiency of photosystem II (PSII) to assess photosynthetic performance [32].

- Thermal Infrared Imaging: Capture canopy temperature, an indicator of stomatal conductance and transpiration rate [32].

- Hyperspectral Imaging: Acquire leaf reflectance data to compute vegetation indices related to pigment content and water status [32].

- Data Integration and Analysis:

- Use software to extract traits from each sensor's data.

- Analyze temporal trends to identify early, late, and recovery responses. For example, waterlogging may cause a rapid drop in PSII efficiency, while drought may cause a gradual increase in canopy temperature [32].

- Plant Preparation and Growth:

The logical relationship between stressors, sensed parameters, and derived physiological traits is shown below:

Reference Tables for Experimental Design and Analysis

Table 1: High-Throughput Phenotyping Platforms and Their Applications

| Platform Name | Primary Function | Traits Recorded | Crop Example | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHENOPSIS | Phenotyping plant responses to soil water stress | Plant growth and water status | Arabidopsis thaliana | [34] |

| LemnaTec 3D Scanalyzer | Non-invasive screening for salinity tolerance | Various salinity tolerance traits | Rice (Oryza sativa) | [34] |

| RSAvis3D (X-ray CT) | 3-D visualization of root system architecture | Root architecture (radicle, crown roots) | Rice (Oryza sativa) | [31] |

| BreedVision | Field-based phenotyping for agronomic traits | Lodging, plant moisture content, biomass yield | Triticale | [34] [33] |

| Multi-Sensor Platform | Assessing morpho-physiological responses to combined stresses | Plant volume, chlorophyll fluorescence, canopy temperature, leaf reflectance | Potato (Solanum tuberosum) | [32] |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for HTP Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function in HTP Experiments | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Calcined Clay (e.g., Turface) | Uniform particle size growth medium that improves root-to-soil contrast in X-ray CT and allows for good aeration and water holding capacity. | Used in X-ray CT-based 3-D root phenotyping to facilitate automatic root segmentation [31]. |

| Klasmann Substrate 2 | A standardized, peat-based potting soil mixture that provides a consistent and reproducible environment for plant growth in pot experiments. | Served as a primary component of the soil mixture in a multi-sensor phenotyping study on potato [32]. |

| Blue Mats / Holders | Provides a uniform, high-contrast background color that simplifies the separation of plant pixels from the background during image segmentation and analysis of above-ground parts. | Placed on the soil surface in pot experiments to enable accurate segmentation of RGB images [32]. |

| Sensor Calibration Standards | Reference materials used to calibrate imaging sensors (e.g., thermal, hyperspectral) to ensure accurate and reproducible measurements across different time points and instruments. | Essential for converting raw sensor data into meaningful physiological units (e.g., temperature, reflectance indices) [32]. |

Integrating HTP Data to Decipher Biological Variation in Stress Response

Handling biological variation is a central challenge in plant stress response studies. HTP addresses this by enabling high-resolution, longitudinal phenotyping of large populations, thus capturing both inter- and intra-genotypic variability [34] [33].

- Forward and Reverse Phenomics: HTP supports two complementary approaches. Forward phenomics screens large populations (e.g., mapping populations, germplasm collections) to identify genotypes with desirable stress response traits. Reverse phenomics delves into the mechanistic basis of known traits by enabling detailed physiological profiling, helping to bridge the genotype-to-phenotype gap [33].