Optimizing Predictive Models in Plant Biosystems Design: From Foundational Concepts to Biomedical Applications

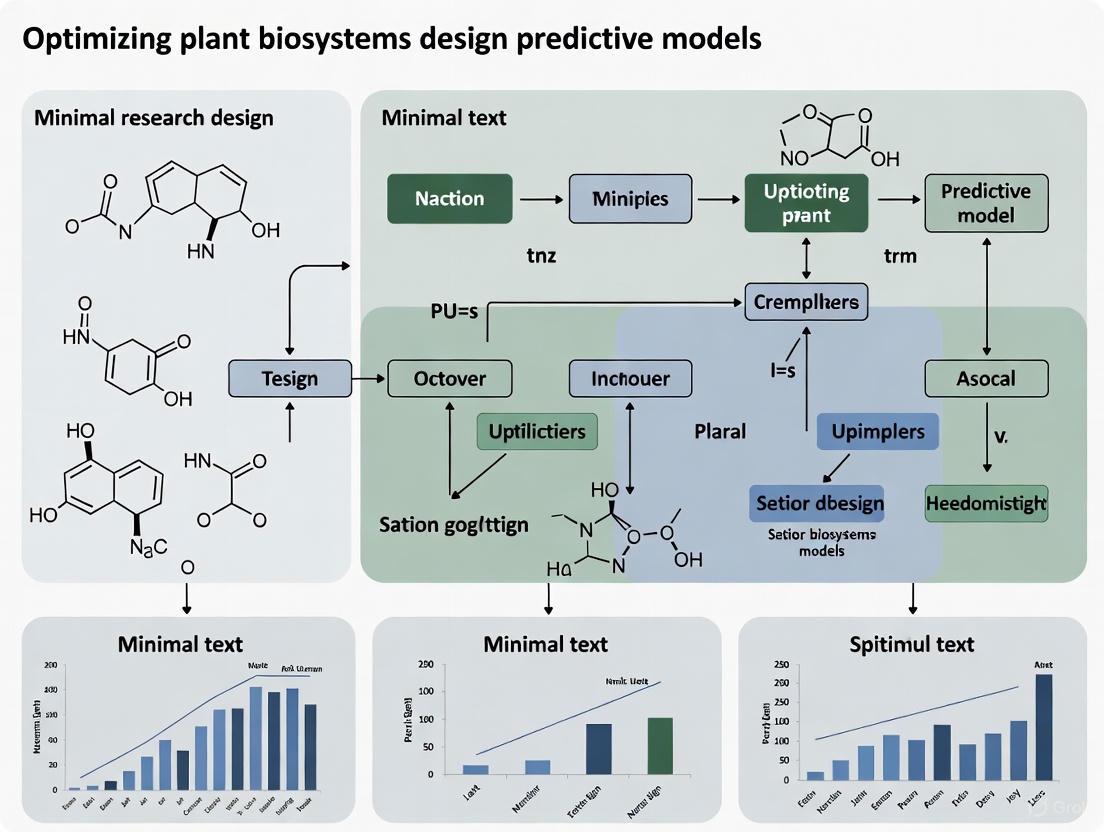

This article provides a comprehensive examination of cutting-edge strategies for optimizing predictive models in plant biosystems design, a field poised to revolutionize sustainable biomolecule production for biomedical applications.

Optimizing Predictive Models in Plant Biosystems Design: From Foundational Concepts to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of cutting-edge strategies for optimizing predictive models in plant biosystems design, a field poised to revolutionize sustainable biomolecule production for biomedical applications. We explore foundational theoretical frameworks including graph theory and mechanistic modeling that underpin modern plant biosystems design. The content details methodological advances in synthetic biology, omics integration, and computational tools for pathway prediction and engineering. We address significant troubleshooting challenges in model accuracy, multi-scale integration, and experimental validation, while presenting rigorous validation frameworks and comparative analyses of model performance. Targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current capabilities and future directions for leveraging designed plant systems as biofactories for therapeutic compounds and drug precursors.

Theoretical Foundations and Emerging Paradigms in Plant Biosystems Modeling

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Hub

This section addresses common technical challenges encountered when using graph theory to model plant biosystems, providing practical solutions to streamline predictive model research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How can I prevent node and edge overlaps in my network layout to improve clarity?

Applying the overlap attribute in your layout algorithms is the primary solution. For complex networks with many nodes and edges, set overlap to a mode like scale or false (depending on your layout engine) before creating the graphs to minimize unnecessary intersections and improve visual readability. [1]

Q2: What is the correct method to enlarge a graph layout without disproportionately scaling node sizes or text?

Avoid using height and width node attributes for this purpose. Instead, use global graph attributes. For dot layouts, adjust nodesep (separation between nodes) and ranksep (separation between ranks). For fdp or neato layouts, increase the len attribute on edges. You can also use the ratio attribute with size; setting ratio=fill or ratio=expand will scale the layout to fit the desired dimensions. [2]

Q3: How do I create edges that connect cluster boundaries instead of individual nodes within them?

This requires two steps. First, set the graph attribute compound=true. Second, when defining an edge, specify the ltail (logical tail) and/or lhead (logical head) attributes with the names of the clusters. Ensure the real head node is inside the cluster specified by lhead and the real tail node is inside the cluster specified by ltail. [2]

Q4: How can I use multiple colors within a single node's label?

Standard labels do not support this. You must use HTML-like labels. Enclose the label within < > and use HTML tags such as <FONT COLOR="COLORNAME"> to change colors for specific text segments. [3]

Q5: My PDF output does not have clickable links even though I used the URL attribute. How can I fix this?

The direct PDF output (-Tpdf) does not support embedded links. To create PDFs with clickable elements, first generate PostScript output with -Tps2, then use an external converter like epsf2pdf or ps2pdf to convert it to PDF. The URL tags are preserved in the PostScript and will be functional in the final PDF. [2]

Graphviz Visualization Guides

Diagram 1: Basic Plant Protein Interaction Network

This DOT script creates a simple protein interaction network, demonstrating node coloring and cluster usage.

Diagram 2: Multi-Layer Experimental Integration Workflow

This diagram visualizes a workflow for integrating multi-omics data into a cohesive network model.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details key reagents, tools, and software essential for constructing and analyzing dynamic biological networks in plant systems.

| Item Name | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| igraph [4] | A library for network analysis; supports topological and centrality analysis for identifying key nodes and structures in biological networks. [4] |

| Cytoscape [4] | A widely used biological network analysis platform; supports many data formats and is customizable. Plugins like BiNGO enable gene ontology enrichment analysis. [4] |

| VANTED [4] | A network analysis software that supports systems biology data formats like SBML and KGML; used for visualizing and analyzing metabolic and regulatory networks. [4] |

| Pathview [4] | An R/Bioconductor package for pathway-based data integration and visualization, mapping omics data onto KEGG pathway graphs. [4] |

| SBML (Systems Biology Markup Language) [4] | A standard format for representing computational models of biological processes; essential for sharing and simulating metabolic reconstructions. [4] |

| Brewer Color Schemes [5] [6] | A set of color schemes (e.g., oranges9, greens9) licensed for academic use, ideal for creating clear, publication-quality network diagrams in Graphviz. [5] [6] |

| GeneMANIA [4] | A web-based tool for constructing interaction networks from genetic and physical interaction data, helping to predict gene function. [4] |

| CellDesigner [4] | A structured diagram editor for drawing gene-regulatory and biochemical networks, which can be stored in SBML format. [4] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental difference between a simulation-centric and a phenotype-centric modeling approach?

The simulation-centric approach involves sampling parameter values, running simulations of the non-linear differential equations, and comparing results with experimental data to find an acceptable fit. In contrast, the phenotype-centric approach first uses linear analysis methods to identify and enumerate the entire repertoire of biochemical phenotypes for a model. If the experimentally observed phenotype is present, the method then predicts a full set of parameter values that will realize it, without requiring prior knowledge of parameter values [7].

FAQ 2: How can mechanistic models help interpret transcriptomic or genomic data?

Mechanistic models provide a natural bridge from variations in genotype (e.g., gene activity from transcriptomics) to variations in phenotype (e.g., cell functional behavior). They are built over graphs representing biological knowledge of functional relationships among proteins. These models can transform a gene expression matrix into a signaling circuit activity matrix, allowing researchers to interpret the downstream consequences that gene expression levels have over signaling circuits and, ultimately, over cell functionality like proliferation or death [8].

FAQ 3: My model contains metabolic cycles and conservation relationships. Will this cause problems, and how can they be resolved?

Yes, these topologies can lead to special, under-determined cases and matrix singularities. However, advanced software tools like the Design Space Toolbox v.3.0 (DST3) can automatically identify and characterize the additional biochemical phenotypes that arise from these features. DST3's computational engine can handle singularities from cycles, metabolic imbalances, and conservation constraints, which are common in metabolic networks with reversible reactions and signaling cascades with conservation relationships [7].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Inability to find parameter values that realize the desired biological phenotype.

- Question: My model simulations do not produce the expected biological behavior, and I cannot find parameter values that make it work. What should I do?

- Solution:

- Switch Modeling Paradigms: Instead of the conventional simulation-centric approach, employ a phenotype-centric approach using tools like the Design Space Toolbox (DST3) [7].

- Enumerate Phenotypes: Use the tool to systematically enumerate all possible biochemical phenotypes inherent to your model's structure.

- Check for Presence: Verify if your experimentally observed phenotype is contained within this enumerated repertoire. If it is not present, this indicates a fundamental problem with the model structure or hypothesis, and the model should be re-evaluated or eliminated [7].

- Predict Parameters: If the phenotype is present, use the tool's linear methods to predict a full set of parameter values that will guarantee the system realizes that specific phenotype [7].

Problem 2: Low robustness or reliability of the model's predictions.

- Question: My model is highly sensitive to tiny changes in parameter values, making its predictions unreliable. How can I improve its robustness?

- Solution:

- Assess Global Robustness: Calculate the product of the global tolerances for all parameters in log-coordinates. This metric is a proxy for the phenotype's volume in parameter space and its associated global robustness [7].

- Compare Phenotypes: If multiple model variants or phenotypic regions can produce similar output, compare their global robustness measures. A larger "volume" in parameter space suggests a more robust phenotype that is less sensitive to parameter variation [7].

- Select Robust Configuration: Favor the model or parameter region with the higher global robustness measure for more reliable predictions.

Problem 3: Model fails during simulation or analysis due to singularities from cycles or conservations.

- Question: My analysis software fails or throws errors related to singular matrices, which I suspect is due to moiety conservations or reaction cycles in my network.

- Solution:

- Use Compatible Tools: Ensure you are using a modeling tool capable of automatically handling these topological features. The Design Space Toolbox v.3.0 (DST3), for example, was specifically expanded to identify and resolve matrix singularities arising from cycles, conservations, and metabolic imbalances [7].

- Recast Model: For tools with limited capabilities, recast your system of Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs) into a Differential-Algebraic Equation (DAE) system. The algebraic equations can explicitly account for the conservation relationships, resolving the singularity [7].

- Independent Verification: After resolving the singularities, use an integrated ODE/DAE solver to simulate the full system dynamically. This provides an independent methodology to confirm the results obtained from the Design Space analysis [7].

Problem 4: Translating a qualitative pathway into a computable model for analyzing functional consequences.

- Question: I have a qualitative signaling pathway from a database like KEGG. How can I use it to model specific cell functions and predict the effect of perturbations?

- Solution:

- Decompose into Circuits: Decompose the larger pathway into its constituent signaling circuits. A circuit is an elementary functional entity connecting one or more receptors to an effector protein that triggers a specific cell function [8].

- Implement Propagation Rule: Use a recursive algorithm to simulate signal propagation. For a node

n, the signal intensityS_nis calculated as its normalized expression value multiplied by the product of(1 - S_a)for all activating inputs and(1 - S_i)for all inhibitory inputs [8]. - Build Activity Matrix: Apply this rule across all circuits to transform your gene or protein expression data matrix into a circuit signaling activity matrix [8].

- Perturbation Analysis: Use this model to simulate interventions (e.g., knock-outs, drug inhibitions) by altering the normalized expression value

v_nof the target node and re-calculating the signal transduction through the circuits it affects [8].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Detailed Methodology: Phenotype-Centric Modeling with Design Space

This protocol outlines the process for identifying biochemical phenotypes and predicting corresponding parameters without a priori parameter knowledge [7].

- System Formulation: Cast your biochemical system in Generalized Mass Action (GMA) form within the Design Space Toolbox v.3.0 (DST3) software.

- The GMA form is:

dX_i/dt = Σ α_ik Π X_j^g_ijk - Σ β_ik Π X_j^h_ijkfori = 1,..., n_c(chemical variables), and0 = Σ α_ik Π X_j^g_ijk - Σ β_ik Π X_j^h_ijkfori = (n_c+1),..., n(auxiliary variables) [7].

- The GMA form is:

- Dominant S-System Identification: For each equation in the system, the software automatically identifies one positive and one negative term that are momentarily dominant, forming a piecewise power-law approximation (S-System).

- Steady-State Solution: The steady-state equations

0 = α_i_pi Π X_j^g_ij_pi - β_i_qi Π X_j^h_ij_qiare solved analytically in logarithmic coordinates. - Design Space Enumeration: The software enumerates all combinations of dominant terms (the "design space"), each defining a distinct biochemical phenotype.

- Phenotype Selection: From the enumerated list, select the phenotype(s) that correspond to your experimentally observed biological behavior.

- Parameter Prediction: For the selected phenotype(s), the tool predicts the sets of parameter values that will realize it.

- Robness & Validation: Use the integrated ODE/DAE solvers in DST3 to dynamically simulate the full system with the predicted parameters and validate the expected behavior [7].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential software tools and their functions in mechanistic modeling.

| Tool / Resource Name | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Design Space Toolbox v.3.0 (DST3) [7] | Phenotype-centric modeling without a priori parameters; handles system singularities. | Predicting parameter values for desired phenotypes in biochemical systems. |

| HiPathia (R/Bioconductor, Cytoscape, Web Tool) [8] | Mechanistic modeling of signaling pathways; estimates signaling circuit activities from gene expression. | Interpreting transcriptomic data and simulating drug/mutation effects. |

| Docker [7] | Containerization platform for software distribution. | Simplified and portable installation of complex toolchains like DST3. |

| Biochemical Network Integrated Computational Explorer (BNICE) [9] | Computer-aided design tool for identifying metabolic genes and pathways. | Metabolic pathway design for engineering microbes (e.g., Clostridia). |

| CRISPR-AID / HI-CRISPR [9] | Genome-scale engineering tools for multigene disruptions and activation. | High-throughput genetic manipulation of non-model yeast and microbes. |

Quantitative Data in Mechanistic Modeling

Table 2: Key quantitative metrics and constraints in mechanistic modeling.

| Metric / Constraint | Typical Value / Formula | Significance / Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Global Robustness (Tolerance Product) [7] | Product of global tolerances in log-coordinates | Proxy for the "volume" of a phenotype in parameter space; higher value indicates greater insensitivity to parameter variation. |

| Enhanced Color Contrast (Text) [10] | ≥ 7:1 (standard text); ≥ 4.5:1 (large text) | WCAG guideline for visual accessibility; ensures diagrams and software interfaces are readable. |

| Signal Intensity (HiPathia) [8] | S_n = v_n · Π (1-S_a) · Π (1-S_i) |

Recursive rule for calculating signal transduction at node n in a signaling circuit. |

| S-System Steady-State [7] | 0 = α_i_pi Π X_j^g_ij_pi - β_i_qi Π X_j^h_ij_qi |

The steady-state equation for the dominant S-system, which is solved analytically. |

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Modeling Strategy Decision Flow

Signaling Circuit with Feedback

Transcriptomic Data Analysis Workflow

Core Concepts: Genetic Stability in Plant Biosystems Design

What is genetic stability in the context of engineered plant systems, and why is it a critical parameter?

Genetic stability refers to the faithful maintenance of introduced genetic constructs and their intended function across plant generations, without unintended rearrangement, silencing, or drift. It is a critical parameter because it ensures that designed traits—such as disease resistance, stress tolerance, or biofuel production characteristics—are reliably expressed in subsequent generations, which is fundamental for the commercial viability and environmental safety of engineered crops [11] [9]. Instability can lead to the loss of these valuable traits, rendering the engineering effort ineffective and potentially wasting significant research and development resources.

What are the primary biological mechanisms that can lead to genetic instability?

The primary mechanisms include:

- Somatic Rearrangement: Unintended recombination or rearrangement of the inserted DNA within the plant's genome, which can disrupt the function of the introduced genes [9].

- Transgene Silencing: Epigenetic mechanisms, such as DNA methylation or histone modification, that can lead to the silencing of the introduced transgene, preventing the expression of the desired trait [12].

- Genetic Drift: In small populations or during prolonged tissue culture phases, random changes can accumulate, leading to a loss of the engineered trait [13].

- Position Effects: The location in the genome where a transgene is inserted can affect its expression and stability, based on the surrounding chromatin environment [9].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide: Addressing Unstable or Declining Transgene Expression

Problem: An engineered trait shows strong initial expression but declines or becomes variable in subsequent plant generations.

| Step | Action | Rationale & Technical Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Diagnose | Confirm instability via molecular analysis (e.g., PCR, Southern blot, RNA-seq). | Quantify transgene copy number, integrity, and mRNA expression levels to distinguish between transcriptional silencing and post-transcriptional effects [12]. |

| 2. Contain | Isolate the unstable line and maintain a separate, well-documented stock. | Prevents cross-contamination of stable lines and preserves a record of the instability event for further study [14]. |

| 3. Solve | A. Re-engineer using different genetic parts: Use matrix attachment regions (MARs) or different promoters to insulate the transgene from positional effects.B. Utilize site-specific integration: Employ CRISPR-based tools to target the transgene to a known genomic "safe harbor" locus that supports stable expression [9]. | MARs can create a more favorable chromatin environment. Targeted integration avoids the unpredictable effects of random insertion [9]. |

| 4. Optimize | A. Screen subsequent generations (T1, T2, etc.) under selective pressure or via genotyping.B. Incorporate multi-omics data (epigenomics, transcriptomics) into predictive models. | Longitudinal screening identifies stable lines. Systems-level data helps refine models to predict stable integration sites and construct designs [9] [12]. |

Guide: Managing Contamination in Plant Tissue Culture

Problem: Microbial contamination (bacteria, fungi, yeast) or oxidative browning threatens the survival of engineered plant explants in tissue culture, a critical phase for plant regeneration.

| Step | Action | Rationale & Technical Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Diagnose | Visually inspect cultures. Cloudy medium indicates bacteria; fuzzy growth suggests fungi; dark brown exudate points to oxidative browning [14]. | Accurate identification is essential for applying the correct countermeasure. |

| 2. Contain | Immediately remove and autoclave contaminated vessels. Do not open contaminated plates near clean cultures [14]. | Prevents the spread of airborne spores or microbes to other valuable experimental lines. |

| 3. Solve | A. For microbial contamination: Add broad-spectrum biocides like Plant Preservative Mixture (PPM) at 0.5-2.0 mL/L to the culture medium. For bacterial issues, antibiotics like cefotaxime can be used with caution [14].B. For oxidative browning: Add antioxidants to the medium, such as ascorbic acid (100-200 mg/L) and citric acid (50-150 mg/L). For severe cases, use adsorbents like activated charcoal (1-3 g/L) [14]. | PPM is heat-stable and effective against a wide range of microbes. Antioxidants quench reactive oxygen species, while adsorbents remove phenolic compounds from the medium [14]. |

| 4. Optimize | A. Pre-soak explants in an antioxidant solution before culture initiation.B. Incubate cultures in darkness for the first 1-2 weeks.C. Always run a pilot study to determine the optimal concentration of additives for your specific plant species [14]. | A synergistic approach combining chemical additives with cultural practices significantly increases success rates. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Longitudinal Tracking of Genetic Stability

Objective: To monitor the persistence and consistent expression of an engineered construct over multiple plant generations.

Materials:

- Seeds or plant tissue from each generation (T0, T1, T2, etc.)

- DNA/RNA extraction kits

- PCR or qPCR reagents

- Sequencing reagents or facilities

- Relevant chemicals and growth media for phenotypic assays

Methodology:

- Sample Collection: Systematically collect leaf tissue from a defined number of individuals (e.g., n=20) per generation at the same developmental stage.

- Genotypic Analysis:

- Extract genomic DNA.

- Perform PCR to confirm the presence of the transgene.

- For a more thorough analysis, use Southern blotting or long-read sequencing to assess transgene copy number and integrity [9].

- Phenotypic Analysis:

- Subject plants to the relevant selective pressure (e.g., herbicide application, drought stress) or measure the output trait (e.g., lipid content, biomarker fluorescence) [9].

- Use high-throughput phenotyping where possible to gather quantitative data on trait expression.

- Transcriptomic Analysis:

- Extract RNA from a subset of plants.

- Perform RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) or RT-qPCR to quantify the expression levels of the introduced genes [12].

- Data Integration: Correlate genotypic and phenotypic data across generations. A stable line will show consistent genotypic presence and predictable, uniform phenotypic expression over multiple cycles.

This protocol directly supports the refinement of predictive models by generating the longitudinal, multi-layered data needed to train algorithms on the factors influencing stability [12].

Protocol: Assessing Stability Under Abiotic Stress

Objective: To determine if environmental stresses accelerate genetic instability or transgene silencing.

Materials:

- Stable transgenic plant lines and null-segregant controls

- Growth chambers for controlled environmental stress (e.g., salinity, drought, heat)

- Materials for molecular analysis (as in Protocol 3.1)

Methodology:

- Experimental Design: Divide clonal plant material or seeds from the same generation into a control group and stress-treated groups.

- Stress Application: Apply a defined, sub-lethal level of abiotic stress (e.g., 150 mM NaCl for salinity, water withholding for drought) for a specific duration during a key growth stage.

- Recovery and Progeny Advancement: Allow stressed plants to recover and set seed.

- Comparative Analysis: In the next generation (e.g., T2), compare the progeny of stressed and non-stressed parents for:

- Transgene presence and structure (as in Protocol 3.1).

- Expression levels of the transgene.

- Penetrance and strength of the engineered phenotype.

- A significant deviation in the progeny of stressed plants indicates that the stressor may have induced epigenetic changes or selected for genetic instability, a critical parameter for predictive models aiming to design crops for marginal environments [9].

Predictive Modeling & Computational Aids

Workflow for Model-Driven Stability Prediction

The following diagram illustrates an integrated computational and experimental workflow for predicting genetic stability.

The Evolutionary Design Cycle in Bioengineering

This diagram conceptualizes the engineering design process as an evolutionary cycle, which is fundamental to understanding and optimizing for genetic stability.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Genetic Stability Research

| Reagent / Solution | Function in Stability Research | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Plant Preservative Mixture (PPM) | A broad-spectrum biocide used in plant tissue culture to prevent microbial contamination, thereby protecting the viability of engineered plant explants [14]. | Heat-stable; can be added before autoclaving. Optimal concentration (0.5-2.0 mL/L) should be determined for each plant species. |

| Antioxidants (Ascorbic Acid, Citric Acid) | Mitigates oxidative browning in tissue culture by quenching reactive oxygen species, improving the survival and health of sensitive engineered plant tissues [14]. | Often used in combination for a synergistic effect. Requires filter sterilization if added post-autoclave. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | Provides comprehensive analysis of transgene integration site, copy number, and potential rearrangements. RNA-seq assesses transcriptomic stability [15] [12]. | Critical for generating high-resolution genotypic data for predictive model training and validation. |

| CRISPR-Cas Systems | Enables precise, site-specific integration of transgenes into genomic "safe harbors," a key strategy for improving long-term stability from the design phase [9]. | Requires careful design of guide RNAs and donor DNA templates. Efficiency varies by plant species. |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines | Computational tools for analyzing multi-omics data (genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics) to identify patterns and features correlated with genetic stability [9] [12]. | Essential for transforming large datasets into predictive insights. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How can AI and machine learning improve the prediction of genetic stability?

AI and machine learning can analyze complex, high-dimensional datasets (e.g., multi-omics, historical stability data, construct features) to identify non-linear patterns and subtle correlations that are not apparent through traditional analysis [12]. These models can learn which genomic contexts, sequence motifs, or epigenetic marks are predictive of stable expression, allowing researchers to score and prioritize designed constructs in silico before moving to costly and time-consuming lab experiments [15] [12]. This transforms the process from one of trial-and-error to a predictive, knowledge-driven discipline.

Our team is new to plant biosystems design. What is the most common conceptual pitfall to avoid?

A common pitfall is treating biological engineering like classical mechanical engineering, where parts are standardized and systems are perfectly modular and predictable. Biology is inherently complex and evolved; it displays emergence, adaptation, and context-dependency [13]. A successful approach acknowledges this by embracing an iterative design-build-test-learn cycle (See Fig. 2). You must plan for multiple rounds of testing and refinement, using data from each cycle to inform the next. Assuming your first design will work perfectly in a living, evolving plant system often leads to frustration. Failure is a feature of the learning process, not a bug [16].

What are the key regulatory considerations for ensuring the environmental stability of a field-trial plant?

Regulatory agencies, such as the USDA APHIS, evaluate the potential for gene flow from the engineered plant to wild relatives and the potential for the plant itself to become a weed [11]. A key part of this assessment is demonstrating genetic stability. If a construct is unstable, it could lead to unpredictable traits that pose an environmental risk. Therefore, comprehensive data on the genetic and phenotypic stability of the engineered trait across several generations in confined trials is a critical component of a regulatory submission [11]. This ensures that the plant being evaluated for deregulation is the same one that will be commercially deployed.

The Shift from Descriptive to Predictive Frameworks in Plant Biomechanics

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core difference between descriptive and predictive research in plant biomechanics?

Descriptive research in plant biomechanics focuses on observing and qualitatively describing mechanical phenomena, such as noting increased stem "hardness" or a greater bending degree. In contrast, predictive research uses quantitative data, computational models, and mechanical theories to forecast plant behavior. It shifts from simple trial-and-error approaches to innovative strategies based on predictive models of biological systems, enabling the anticipation of phenomena like lodging resistance before they occur in the field [17] [18].

Q2: My predictive models for stalk lodging are inaccurate. What are common sources of experimental error in phenotyping?

A primary source of error in field phenotyping for traits like bending stiffness and strength is incorrect device placement and calibration. Specifically, a load cell height miscalibration can introduce errors as large as 130% in bending stiffness and 50% in bending strength. Errors of 15-25% in bending stiffness and 1-10% in bending strength are common. Key sources of error include:

- Incorrect Load Cell Height: Inaccurate measurement of the moment arm (h) has the most significant impact on calculations [19].

- Horizontal Device Misplacement: Placing the device's pivot point in front of or behind the stalk's base causes the load cell to slide along the stalk, introducing non-normal force measurements [19].

- Vertical Device Misplacement & Characteristic Pivot: During large deflections, a plant stalk's center of curvature is not at its base but at a point approximately 15% of its length from the base. A device that pivots at ground level will conflict with this natural pivot, leading to errors in deflection and force measurements [19].

Q3: How can I improve the accuracy of my mechanical phenotyping data in the field?

To mitigate experimental error, follow these protocols:

- Calibrate Load Cell Height Precisely: Before each measurement, verify and accurately record the load cell height (h). Even small errors are cubed in the bending stiffness calculation (EI=\frac{\phi {\cdot h}^{3}}{3}) [19].

- Ensure Proper Device Placement: Carefully position the device's pivot point as close as possible to the true base of the stalk. Use fixtures or guides to minimize horizontal misplacement [19].

- Account for the Characteristic Pivot: For large-deflection tests, be aware that the characteristic pivot phenomenon may introduce some inherent error. Refined models that account for this can improve accuracy [19].

- Utilize an Artificial Stalk for Calibration: Develop a standardized, artificial stalk (e.g., a tapered carbon fiber rod) to perform a barrage of tests. This helps quantify and systematize the error present in your specific phenotyping platform and operating procedures [19].

Q4: What enabling technologies are driving the shift towards predictive frameworks?

The transition is powered by the integration of advanced computational and experimental tools:

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML): These technologies are used to direct maintenance management, analyze large datasets for condition monitoring, and help spot early anomalies in systems [20].

- Multi-omics and Computational Modeling: Integrating transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics with computational models allows for a systems-level understanding. Computer-aided design (CAD) platforms use this data to guide genome-scale engineering of plants and microbes [18] [9].

- Advanced Simulation Methods: Finite element analysis, molecular dynamics, and coarse-grained models enable the mechanical simulation of complex structures, from molecular systems to whole plant organs [17].

- High-Throughput Phenotyping: Robotics and automated platforms, like the DARLING for lodging resistance, allow for the large-scale collection of biomechanical data, though they require careful error management [19].

- Genome-Scale Engineering: Tools like CRISPR-Cas for genome editing and synthetic biology enable the precise modification of plants to test predictive models, for example, by introducing stress-tolerant genes into bioenergy crops [9].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Measurements in Field-Based Biomechanical Phenotyping

Symptoms: High variance in bending stiffness and strength data from identical genotypes; poor correlation between mechanical properties and field lodging incidence.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

| Step | Action | Technical Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Verify Load Cell Height | Manually confirm the physical height of the load cell from the pivot point with a ruler. Even a small error in h is cubed in the stiffness calculation, leading to major inaccuracies [19]. |

| 2 | Inspect Device Placement | Ensure the device's foot plate is flush with the ground and pivoting directly at the stalk base. The presence of brace roots or uneven soil can lift the pivot, changing the effective moment arm [19]. |

| 3 | Check Sensor Alignment | As the stalk is deflected, observe the load cell. It should remain perpendicular to the stalk segment. If it slides up or down, it indicates a pivot point discrepancy, introducing non-normal forces [19]. |

| 4 | Quantify Systematic Error | Use a standardized artificial stalk to perform repeated tests. This establishes a baseline for the systematic and random error inherent in your specific device and operational protocol [19]. |

| 5 | Refine Data Processing | In your analysis code (e.g., custom MATLAB scripts), ensure the linear portion of the force-deflection curve used for stiffness calculation is consistently defined, typically below 10 degrees of deflection [19]. |

Problem: Failure in Integrating Multi-Scale Data for Predictive Modeling

Symptoms: Inability to reconcile genetic, cellular, tissue, and organ-level data into a functional predictive model; model predictions fail under field conditions.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

| Step | Action | Technical Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Audit Data Quality and Scale | Confirm that data from different scales (e.g., gene expression, cell wall mechanics, tissue stress) have appropriate spatial and temporal resolution. Multi-scale integration requires standardized metadata [17]. |

| 2 | Select Appropriate Modeling Framework | Choose a model that fits the scale. Use coarse-grained models for molecular-to-cellular scales, finite element analysis for tissue-to-organ scales, and multi-scale models that bridge these levels [17]. |

| 3 | Incorporate Environmental Inputs | Predictive models for field performance must include environmental variables (e.g., wind, soil resistance, gravity). These external mechanical pressures drive morphological adaptations [17]. |

| 4 | Validate with Controlled Experiments | Use genetically engineered lines (e.g., plants with modified cell wall properties or stress-response pathways) to test specific model predictions in controlled environment and field trials [9]. |

| 5 | Iterate with AI/ML | Employ machine learning to identify key patterns and relationships within large, multi-scale datasets that may not be apparent through traditional analysis, refining the predictive model [17] [20]. |

Experimental Data and Protocols

The following table quantifies the experimental error in biomechanical phenotyping for stalk lodging, based on controlled tests with an artificial maize stalk [19].

Table 1: Experimental Error in Stalk Bending Phenotyping

| Source of Error | Impact on Bending Stiffness | Impact on Bending Strength | Recommended Mitigation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incorrect Load Cell Height | Up to 130% error | Up to 50% error | Precisely calibrate and record height (h) before each test. |

| Horizontal Device Misplacement | Contributes to common 15-25% error range | Contributes to common 1-10% error range | Ensure pivot point is exactly at the stalk base. |

| Vertical Misplacement & Characteristic Pivot | Introduces error in deflection angle and force measurement | Introduces error in maximum force recording | Acknowledge inherent limitation; use for large-deflection tests. |

Key Experimental Protocol: Error Analysis of a Phenotyping Platform

Objective: To identify and quantify the primary sources of measurement error in a field-based biomechanical phenotyping device [19].

Materials:

- Phenotyping device (e.g., DARLING)

- Custom artificial stalk (e.g., tapered carbon fiber rod designed to mimic the moment of inertia of an average maize stalk)

- Precision test fixture with adjustable horizontal and vertical placement

- Data acquisition system (load cell, angle sensor)

- Analysis software (e.g., MATLAB)

Methodology:

- Fixture Setup: Mount the artificial stalk securely in the test fixture. This fixture should allow the phenotyping device to be positioned at defined horizontal (±12.8%, ±6.4%, 0% of load cell height) and vertical (0%, 7.5%, 15% of load cell height) displacements relative to the stalk base.

- Experimental Matrix: Perform a full-factorial test, conducting multiple replicates (e.g., n=10) for each combination of horizontal and vertical positions.

- Controlled Deflection: For each test, deflect the stalk to a standardized angle (e.g., 10° for linear stiffness calculation and 25° as a proxy for strength). Use external sensors on the test fixture, not the device's own sensors, to define the deflection points to ensure consistency across all device placements.

- Data Calculation: For each test, calculate bending stiffness (EI) using Eq. (1) from the linear portion of the force-deflection curve (below 10°). Use the force at 25° deflection as a surrogate for bending strength (S), Eq. (2).

- Error Quantification: Compare the calculated EI and S values across all tests to the "true" values obtained from the ideal device placement (0% horizontal, 0% vertical). Calculate systematic and random error for each source of misplacement.

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Predictive Plant Biomechanics Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools for Predictive Plant Biomechanics Research

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| DARLING-type Phenotyping Platform | A field-deployable device to apply controlled forces to plant stalks and measure bending strength and stiffness, crucial for quantifying lodging resistance [19]. |

| Artificial Reference Stalk | A standardized, reproducible specimen (e.g., tapered carbon fiber rod) used to calibrate phenotyping equipment and quantify systematic measurement error [19]. |

| Finite Element Analysis (FEA) Software | Computational tool to simulate and analyze mechanical stresses, strains, and deformations in complex 3D plant structures across different scales [17]. |

| CRISPR-Cas Genome Editing System | Enables precise modification of plant genes (e.g., those involved in cell wall biosynthesis or stress response) to test hypotheses generated by predictive models [9]. |

| Multi-omics Data Suites | Integrated datasets from genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics that provide the foundational information for building genome-scale models [9]. |

| Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | Allows for high-resolution, nano-scale measurement of mechanical properties, such as cell wall elasticity and stiffness in living plant tissues [17]. |

Knowledge Gaps and Quantitative Challenges in Predictive Modeling

A significant challenge in plant biosystems design is the incomplete mapping of metabolic networks, which limits the predictive power of computational models. Key quantitative data is missing in several areas, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Gaps in Plant Biosystems Design

| Knowledge Gap Area | Specific Quantitative Shortcoming | Impact on Predictive Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Underground Metabolism [21] | Only ~20% of connectable underground reactions have confirmed fitness advantages; full catalytic repertoire is unquantified. | Models underestimate metabolic potential and adaptive pathways for new environments. |

| Multi-scale Model Integration [22] | Kinetic parameters are missing for most enzymes; data from different scales (molecular, cellular, tissue) are not unified. | Whole-cell models are slow, difficult to build, and cannot accurately simulate complex, multi-cellular biosystems. |

| Pathway Reconstruction [23] | For many valuable plant natural products, the biosynthetic pathways and their key regulatory points are not fully identified. | Hinders the rational engineering of plants for the sustainable production of therapeutics and nutraceuticals. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: Our engineered metabolic pathway in Nicotiana benthamiana is producing yields far below model predictions. What are the common failure points and how can we troubleshoot them?

- A: This is a common issue often stemming from metabolic bottlenecks, pathway instability, or cellular toxicity. Follow this systematic troubleshooting guide:

- Verify Gene Expression and Splicing:

- Problem: Transgenes are not expressed, or are incorrectly spliced.

- Solution: Isolate RNA from transfected tissue and perform RT-PCR to confirm the presence and correct size of transcripts for all pathway genes.

- Profile Intermediate Metabolites:

- Problem: A bottleneck at a specific enzymatic step causes accumulation of an intermediate and depletion of the final product.

- Solution: Use LC-MS or GC-MS to profile metabolites. The accumulation of a specific intermediate indicates a problematic enzymatic step that may require codon optimization, enzyme engineering, or co-expression of chaperones [23].

- Check for Product Toxicity or Sequestration:

- Problem: The target product is toxic to host cells or is being sequestered in an inaccessible compartment.

- Solution: Review literature on compound toxicity. Consider engineering product export to the apoplast or fusion tags to direct sequestration to vacuoles [23].

- Test for Gene Silencing:

- Problem: Over time, transgene expression is silenced.

- Solution: Include genetic elements to combat silencing and analyze genomic DNA to confirm pathway integrity.

- Verify Gene Expression and Splicing:

FAQ 2: When attempting to build a predictive metabolic model, we lack kinetic parameters for most plant enzymes. How can we proceed?

- A: The lack of comprehensive kinetic data is a major hurdle. Instead of traditional kinetic modeling, employ these strategies:

- Utilize Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis (COBRA):

- Method: Develop a genome-scale model (GEM) and use Flux Balance Analysis (FBA). FBA finds an optimal flux distribution (e.g., for biomass production) without needing kinetic parameters, by leveraging stoichiometry and constraints on reaction rates [22].

- Protocol: Reconstruct the network from annotated genomes and literature. Define system constraints (e.g., nutrient uptake). Use computational tools like the COBRA Toolbox to simulate growth and predict flux distributions under different conditions.

- Incorporate Heterogeneous Omics Data:

- Method: Constrain your COBRA model with transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data. This integrates condition-specific information, improving prediction accuracy [22].

- Protocol: Map omics data onto the model to deactivate or downregulate reactions when corresponding genes are not expressed or proteins are not detected.

- Apply Bayesian Parameter Estimation:

- Method: For more dynamic models, use Bayesian methods to estimate plausible thermodynamic and kinetic values based on existing data and known principles, providing a probabilistic framework for your model [22].

- Utilize Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis (COBRA):

FAQ 3: Our whole-cell model is computationally expensive and slow to run. How can we improve simulation speed?

- A: Whole-cell models are notoriously computationally intensive. Consider these approaches:

- High-Performance Computing (HPC):

- Solution: Execute the model on HPC platforms. The parallelized architecture can significantly accelerate simulations [22].

- Model Reduction:

- Solution: Identify and aggregate non-critical or redundant processes. Focus computational resources on the core pathways most relevant to your research question.

- Hybrid Modeling with Machine Learning (ML):

- Solution: Develop a hybrid mechanistic-ML model. Train a machine learning algorithm (e.g., an artificial neural network) on the input and output of your whole-cell model to create a faster, surrogate model for rapid predictions [22].

- High-Performance Computing (HPC):

Experimental Protocols for Key Investigations

Protocol 1: Investigating Underground Metabolism in a Plant Chassis

Objective: To experimentally test if an overexpressed enzyme with known underground activity can confer a growth advantage in a specific novel nutrient environment.

Background: Underground reactions are enzyme side activities that occur at low rates but can be wired into the metabolic network. Increasing their activity may allow growth in new conditions [21].

Materials:

- Wild-type and transgenic plant lines (e.g., Arabidopsis or N. benthamiana) overexpressing the target enzyme.

- Control and experimental growth media (e.g., standard medium vs. medium where the underground reaction is predicted to enable utilization of a novel carbon source).

- Equipment for sterile culture and growth monitoring.

Methodology:

- In Silico Prediction: Use flux balance analysis (FBA) on a genome-scale model to identify nutrient conditions where the underground reaction is predicted to create a novel biomass-producing pathway [21].

- Plant Growth Assay:

- Inoculate wild-type and transgenic plant lines in triplicate onto both control and experimental media.

- Grow plants under controlled environmental conditions.

- Monitor growth over time by measuring fresh weight, dry weight, or chlorophyll content.

- Metabolite Validation: Use LC-MS to detect and quantify the novel metabolite produced by the underground reaction in the transgenic lines grown on the experimental medium.

- Data Analysis: Compare growth metrics and metabolite levels between wild-type and transgenic lines on the experimental medium. Statistically significant enhancement in transgenic lines supports the predicted adaptive potential of the underground reaction.

Protocol 2: Multi-Omics Guided Reconstruction of a Plant Biosynthetic Pathway

Objective: To identify and validate unknown genes in a biosynthetic pathway for a target plant natural product.

Background: Integrated omics allows correlation of metabolite production with gene expression to rapidly pinpoint candidate genes [23].

Materials:

- Plant tissue samples from different developmental stages or treatments that show variation in the target metabolite.

- RNA sequencing and metabolomics profiling facilities.

- Heterologous expression system (e.g., N. benthamiana for transient expression).

Methodology:

- Integrated Omics Profiling:

- Transcriptomics: Perform RNA-Seq on all plant tissue samples.

- Metabolomics: Use LC-MS to quantitatively profile the target metabolite and potential intermediates in the same samples.

- Correlation and Candidate Gene Identification:

- Conduct co-expression analysis to identify genes whose expression patterns strongly correlate with the accumulation of the target metabolite.

- Use bioinformatics tools to annotate these candidate genes (e.g., as cytochrome P450s, methyltransferases).

- Functional Validation in a Heterologous System:

- Clone the candidate genes into expression vectors.

- Infiltrate N. benthamiana with Agrobacterium strains containing the candidate genes, either individually or in combination [23].

- Harvest leaf tissue after several days and extract metabolites.

- Analysis: Analyze the extracts via LC-MS for the presence of the target metabolite or expected intermediates, confirming the function of the candidate gene in the pathway.

Visualization of Pathways and Workflows

Experimental Workflow for Underground Metabolism

Multi-Omics Guided Pathway Discovery

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Plant Biosystems Design

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Nicotiana benthamiana [23] | A versatile plant chassis for transient gene expression and rapid pathway prototyping via Agrobacterium-mediated infiltration. | High biomass, fast growth, high transgene expression. Not for stable production. |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens [23] | A vector for delivering genetic material into plant cells. Essential for transient expression in N. benthamiana and stable transformation. | Different strains (e.g., GV3101, LBA4404) have varying efficiencies. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Systems [23] | For precise genome editing (knock-out, knock-in, base editing) to engineer plant hosts or study gene function. | Delivery method (Agrobacterium, biolistics) and efficiency vary by species. |

| LC-MS / GC-MS [23] | Mass spectrometry platforms for targeted and untargeted metabolomics to identify and quantify metabolites, validating pathway activity. | Critical for measuring pathway intermediates and final products. |

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) Software [22] | Computational tool for predicting metabolic fluxes in a genome-scale model, used to predict outcomes of metabolic engineering. | Requires a high-quality, genome-scale metabolic reconstruction. |

| DNA Synthesis & Assembly Tools [23] | For de novo synthesis and assembly of genetic parts and multi-gene pathways for expression in plant chassis. | Enables codon optimization and construction of complex synthetic circuits. |

Advanced Methodologies and Computational Tools for Predictive Design

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the core components of a CRISPR-Cas system, and how do they function in genome editing? The CRISPR-Cas system consists of two core components: a guide RNA (gRNA) and a Cas protein (such as Cas9). The gRNA is a short RNA sequence that is programmed to lead the Cas protein to a specific matching DNA sequence. Once the target DNA is found, the Cas protein binds to the DNA and cuts it, like molecular scissors. This cut disrupts the targeted gene. After the DNA is cut, the cell's natural repair mechanisms are activated, which can be harnessed to introduce specific changes or "edits" to the DNA sequence. [24] [25]

Q2: How does CRISPR-Cas9 compare to other genome editing tools like TALENs? CRISPR-Cas9 is generally more efficient and customizable than older tools like TALENs (Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases) or ZFNs (Zinc Finger Nucleases). A key advantage is that the CRISPR-Cas9 system itself is capable of cutting DNA strands, so it does not need to be paired with separate cleaving enzymes. Furthermore, CRISPR guide RNAs are easier to design and synthesize compared to the engineered proteins required for TALENs, and CRISPR can target multiple genes simultaneously. [24] [26]

Q3: What are the common issues causing low editing efficiency, and how can they be addressed? Low editing efficiency can stem from several factors. The table below outlines common issues and their solutions.

| Issue | Possible Cause | Troubleshooting Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Low Cleavage Efficiency | Inefficient gRNA design; chromatin inaccessibility [26] | Design multiple gRNAs targeting different sites; test gRNA efficiency in vitro; target genomic regions with open chromatin. |

| Poor HDR Efficiency | Dominant error-prone NHEJ repair pathway [25] | Use single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs) with >50 nt homology arms [26]; synchronize cell cycle to favor HDR. |

| Inefficient Delivery | Cell barriers (e.g., plant cell wall); degradation of components [25] [27] | Optimize delivery method (e.g., electroporation, nanoparticles, viral vectors); use Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes to reduce off-targets. |

Q4: What are "off-target effects," and how can they be minimized? Off-target effects occur when the CRISPR system cuts the DNA at an unintended, similar-but-not-identical site in the genome. [25] To minimize this risk:

- Careful gRNA Design: Use specialized software to design gRNAs with minimal similarity to other genomic sequences. [26]

- Use High-Fidelity Cas Variants: Engineered Cas proteins like SpCas9-HF1 or eSpCas9 are designed to reduce non-specific binding. [27]

- Optimize Delivery and Concentration: Using purified Cas9-gRNA RNP complexes instead of DNA plasmids can reduce the time the system is active in the cell, thereby limiting off-target activity. [25] [27]

Q5: Beyond cutting DNA, what other functions can CRISPR systems perform? The CRISPR toolbox has expanded far beyond simple DNA cutters. By using a catalytically "deactivated" Cas protein (dCas9) that can target DNA but cannot cut it, researchers have created powerful regulatory tools: [24] [28] [27]

- CRISPR interference (CRISPRi): dCas9 blocks transcription by physically obstructing RNA polymerase, effectively turning a gene off. [28]

- CRISPR activation (CRISPRa): dCas9 is fused to transcriptional activator domains to enhance gene expression, effectively turning a gene on. [28] [27]

- Epigenetic Editing: dCas9 can be fused to enzymes that add or remove epigenetic marks (e.g., methyl or acetyl groups) to modulate gene expression stably. [27]

Q6: What are synthetic gene circuits, and how is CRISPR used to build them in plants? Synthetic gene circuits are engineered networks of genetic elements that process information and control gene expression in a cell, analogous to electronic circuits. [28] [29] CRISPRi is particularly useful for building these circuits because it is highly modular and programmable; simply changing the gRNA allows you to rewire the circuit's function. Researchers have successfully built logic gates (e.g., NOT, NOR) in plants using CRISPRi. For example, a NOR gate produces an output only when neither of two input signals (e.g., specific gRNAs) is present. [30] [29] These gates can be layered to create complex logic, enabling sophisticated spatiotemporal control of gene expression for plant biosystems design. [30]

Q7: My CRISPRi-based gene circuit is not functioning as predicted. What should I check? Circuit failure can often be traced to imbalances in component expression. Focus on these areas:

- Promoter Strength: The strength of the promoters driving gRNA and dCas9 expression is critical. A strong input promoter may produce so much gRNA that it causes unintended repression, while a weak one may not produce enough to trigger the switch. [29] Systematically test promoters of different strengths.

- gRNA Processing: For circuits expressed from RNA Polymerase II (Pol II) promoters, ensure efficient release of the mature gRNA using ribozymes or tRNA processing systems. [30] [29]

- dCas9 Expression Level: Insufficient dCas9 will limit repression, while extremely high levels may cause toxicity and non-specific effects. Use a well-characterized, constitutive promoter to drive stable dCas9 expression. [30]

Experimental Protocols for Key Techniques

Protocol 1: Implementing a CRISPRi-Based NOR Gate in Plant Protoplasts

This protocol allows for rapid testing of synthetic gene circuits in plant cells before stable transformation. [30] [29]

1. Reagents and Materials

- Plasmid DNA encoding: (i) dCas9 fused to a repressor domain (e.g., SRDX), (ii) Integrator promoter (engineered target), (iii) gRNA expression cassettes.

- Plant material (e.g., Arabidopsis thaliana or Nicotiana benthamiana leaves).

- Enzyme solution for cell wall digestion (e.g., Cellulase, Macerozyme).

- PEG solution (40% w/v PEG 4000).

- MMg solution (0.4 M mannitol, 15 mM MgCl2, 4 mM MES, pH 5.7).

- 96-well plates for transfection and luciferase assays.

2. Step-by-Step Procedure Day 1: Protoplast Isolation

- Harvest young, healthy leaves and slice them into thin strips (0.5-1 mm).

- Submerge the leaf strips in an enzyme solution and incubate in the dark for 3-16 hours with gentle shaking (30-40 rpm) to release protoplasts.

- Filter the protoplast-enzyme mixture through a nylon mesh (70-100 μm) to remove undigested debris.

- Purify the protoplasts by centrifugation in a W5 solution (154 mM NaCl, 125 mM CaCl2, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM MES, pH 5.7) and resuspend in MMg solution at a density of 2x10^5 cells/mL.

Day 1: Protoplast Transfection

- For each sample, combine 10 μg of total plasmid DNA (e.g., 2 μg dCas9, 2 μg integrator-reporter, 3 μg gRNA-A, 3 μg gRNA-B).

- Add 100 μL of protoplast suspension (2x10^4 cells) to the DNA.

- Add an equal volume (100 μL) of 40% PEG solution, mix gently by inverting, and incubate for 15-30 minutes at room temperature.

- Dilute the transfection mixture step-wise with W5 solution and pellet the protoplasts by gentle centrifugation.

- Carefully remove the supernatant and resuspend the protoplasts in 1 mL of culture medium. Transfer to a 96-well plate and incubate in the dark for 16-48 hours.

Day 2: Output Measurement and Data Analysis

- Assay for the circuit's output, typically a luciferase reporter gene under the control of the integrator promoter.

- Lyse the protoplasts and measure both firefly luciferase (circuit output) and Renilla luciferase (internal control) activities using a dual-luciferase assay kit.

- Calculate the normalized repression by comparing luminescence from circuits with and without input gRNAs. Successful NOR gate operation shows high output (reporter expression) only when both input gRNAs are absent. [30]

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the diagram below:

Protocol 2: Optimizing gRNA Design for High-Efficiency CRISPRi

1. Principle Effective CRISPRi repression, especially in plants, requires gRNAs to be designed to specific regions of the target promoter. [29]

2. Procedure

- Identify the Target Promoter Region: Map the promoter of the gene you wish to repress, locating key elements like the Transcriptional Start Site (TSS) and TATA box.

- Select gRNA Binding Sites: Design multiple gRNAs targeting regions immediately upstream and downstream of the TATA box. This area is often most effective for steric hindrance of RNA polymerase. [29]

- Check for Specificity and Off-Target Potential: Use bioinformatics tools (e.g., BLAST, Cas-OFFinder) to ensure the gRNA sequence has minimal homology to other promoter regions in the genome.

- Validate Experimentally: Clone candidate gRNAs into expression vectors and test their repression efficiency in a protoplast transient assay, as described in Protocol 1.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential reagents for working with CRISPR and gene circuits in plant systems.

| Category | Reagent / Tool | Function and Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Effectors | High-Fidelity Cas9 (e.g., SpCas9-HF1) [27] | Reduces off-target effects in editing and regulation. |

| dCas9 transcriptional repressor (dCas9-SRDX) [30] | Core effector for CRISPRi; SRDX domain enhances repression in plants. | |

| Cas12a (Cpf1) [24] | Alternative nuclease/effector; different PAM (TTTV) and staggered cuts can aid editing. | |

| Delivery Tools | Gold microparticles (for biolistics) | For stable transformation of plants recalcitrant to other methods. |

| PEG (for protoplast transfection) [30] | Enables plasmid delivery for rapid transient assays in protoplasts. | |

| Circuit Components | Engineered Integrator Promoters [30] | Promoters engineered with specific gRNA target sites for building logic gates. |

| Inducible Promoters (Dex, Heat) [29] | Allow controlled, temporal expression of circuit inputs (gRNAs). | |

| gRNA Processing Systems (Ribozymes, Csy4) [29] | Essential for processing gRNAs from Pol II transcripts in complex circuits. | |

| Validation Kits | Genomic Cleavage Detection Kit [26] | Streamlines workflow for assessing editing efficiency and validating on-target activity. |

| Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System [30] | Gold standard for quantitative measurement of promoter activity in circuit outputs. |

Biological systems operate as interconnected networks where changes at one molecular level ripple across multiple layers. Multi-omics integration combines data from genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics to create comprehensive biomarker signatures that capture disease complexity with remarkable precision and predictive power. This systems-level perspective reveals emergent properties that are invisible when examining individual omics layers in isolation, making multi-omics signatures more biologically relevant and clinically actionable than single-marker approaches [31].

In plant biosystems design, multi-omics approaches represent a shift from simple trial-and-error methods to innovative strategies based on predictive models of biological systems. These approaches seek to accelerate plant genetic improvement using genome editing and genetic circuit engineering, ultimately supporting the development of improved crop varieties with enhanced nutritional content and stress resilience [18]. Plant metabolomics, a key branch of systems biology, provides crucial insights into the small-molecule metabolites that are vital for growth, development, environmental adaptation, and defense mechanisms in plants [32].

Fundamental Concepts & FAQs

FAQ: What are the primary omics layers integrated in pathway discovery?

Multi-omics integration typically combines several molecular layers [33] [31]:

- Genomics: DNA sequence variations and mutations

- Epigenomics: DNA methylation patterns and chromatin modifications

- Transcriptomics: Gene expression data including mRNA and non-coding RNAs

- Proteomics: Protein expression and post-translational modifications

- Metabolomics: Small-molecule metabolites and metabolic fluxes

FAQ: Why is multi-omics integration superior to single-omics approaches for pathway discovery?

Multi-omics integration provides several key advantages [33] [31]:

- Comprehensive Perspective: Examines multiple molecular levels simultaneously

- Cross-Validation: Findings from different omics layers validate each other

- Improved Biomarker Identification: Considers multiple types of molecular data for more robust biomarkers

- Biological Reality Capture: Reflects the actual interconnected nature of biological systems

FAQ: How does metabolomics contribute to understanding plant biosystems?

Plant metabolites are crucial executors of gene functions and key mediators of plant survival strategies. They serve not only as mediators of energy and material exchange but also as important signaling molecules in response to environmental changes. With over 200,000 metabolites present in plants, and any single plant species potentially containing 7,000–15,000 different metabolites, metabolomics provides a direct functional readout of cellular processes [32].

Technical Specifications & Data Standards

Table 1: Analytical Platforms for Different Omics Layers

| Omics Layer | Primary Technologies | Key Metrics | Data Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolomics | LC-MS, GC-MS, NMR, CE-MS [32] [34] | Metabolite identification, concentration, m/z ratio | Peak lists, concentration values, spectral data |

| Transcriptomics | RNA-seq, microarrays, scRNA-seq [34] | Read counts, FPKM/TPM values, differential expression | FASTQ, BAM, count matrices |

| Genomics | Whole-genome sequencing, WES [31] | Read depth, variant calls, methylation ratios | VCF, BAM, methylation profiles |

| Proteomics | LC-MS/MS, protein arrays [31] | Peptide counts, intensity values, PTM identification | Peak lists, identification files |

Table 2: Multi-Omics Integration Methodologies Comparison

| Integration Type | Description | Advantages | Limitations | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Integration | Combines raw data before analysis [31] | Maximizes information preservation, discovers novel cross-omics patterns | Computationally intensive, requires sophisticated preprocessing | Hypothesis generation, pattern discovery |

| Intermediate Integration | Combines features or patterns from each omics layer [31] | Balances information retention with computational feasibility, incorporates domain knowledge | May miss subtle raw data interactions | Large-scale studies, pathway-focused research |

| Late Integration | Combines results from separate analyses [31] | Maximum flexibility and interpretability, robust against noise | Might miss cross-omics interactions | Modular workflows, validation studies |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Integrated Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Analysis of Plant Samples

Sample Preparation and Data Acquisition [35]:

Sample Collection: Collect plant tissues (e.g., flowers, buds) at different developmental stages. Immediately freeze in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C for RNA and metabolite extraction.

Metabolite Extraction:

- Weigh 50 mg of dried plant material

- Add 1,000 µL extraction solution (methanol:acetonitrile:water, 2:2:1 volume ratio with internal standard)

- Vortex for 30 seconds, grind with ceramic beads at 45 Hz for 10 minutes

- Sonicate for 10 minutes in ice-water bath

- Incubate at -20°C for 1 hour, then centrifuge at 12,000 rpm for 15 minutes at 4°C

- Transfer 500 µL supernatant to EP tube and dry in vacuum concentrator

- Reconstitute with 160 µL acetonitrile:water (1:1 volume ratio)

Metabolomic Analysis:

- Use UPLC system coupled with high-resolution mass spectrometer

- Employ Acquity UPLC HSS T3 column (1.8 μm, 2.1 × 100 mm)

- Mobile phases: 0.1% formic acid in water (A) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (B)

- Perform analysis in both positive and negative ion modes

RNA Extraction and Transcriptomic Sequencing:

- Extract total RNA using specialized kits for plant tissues

- Evaluate RNA quality and concentration

- Perform library preparation and quality assessment

- Conduct sequencing in PE150 mode using Illumina platform

Protocol: Pathway Activation Analysis Using Multi-Omics Data

Data Integration and Pathway Analysis [33]:

Data Preprocessing:

- Normalize data from different omics platforms using quantile normalization or z-score standardization

- Correct for batch effects using ComBat or surrogate variable analysis

- Handle missing data using advanced imputation methods

Differential Analysis:

- Identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) using appropriate statistical thresholds (e.g., FDR < 0.05, |log2FC| > 1)

- Identify differentially abundant metabolites (DAMs) using OPLS-DA with VIP > 1, P < 0.05

- Calculate perturbation factors for pathway analysis

Pathway Activation Calculation:

- Utilize topological pathway analysis methods (SPIA, iPANDA)

- Calculate pathway activation levels using the formula: Acc = B·(I - B)·ΔE

- Integrate non-coding RNA profiles by considering their regulatory effects

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Correlation Between Omics Layers

Possible Causes and Solutions [33] [31]:

- Cause: Technical variability between platforms

- Solution: Implement rigorous batch effect correction and cross-platform normalization

- Cause: Biological time delays between molecular events

- Solution: Incorporate time-series sampling and dynamic modeling approaches

- Cause: Inappropriate integration methodology selection

- Solution: Test multiple integration approaches (early, intermediate, late) and select based on biological question

Problem: High Dimensionality and Small Sample Sizes

Solutions and Methodologies [31]:

- Employ regularization techniques (elastic net regression, sparse PLS)

- Utilize dimension reduction methods (PCA, non-negative matrix factorization)

- Implement machine learning approaches designed for sparse data

- Incorporate biological knowledge through network-based integration

Problem: Inconsistent Pathway Analysis Results

Troubleshooting Steps [33]:

- Verify pathway database consistency and curation methods

- Validate topological analysis methods against known biological pathways

- Check parameter settings for statistical significance thresholds

- Confirm appropriate control samples are used for baseline comparisons

Signaling Pathways & Workflow Visualization

Multi-Omics Workflow for Pathway Discovery

Regulatory Networks in Pathway Activation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Multi-Omics Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methanol with Internal Standards | Metabolite extraction and preservation [35] | LC-MS sample preparation | HPLC grade with 2 mg/L internal standards |

| RNAprep Pure Plant Kit | RNA extraction from polysaccharide-rich plants [35] | Transcriptomic sequencing | Designed for polyphenol-rich tissues, maintains RNA integrity |

| Acquity UPLC HSS T3 Column | Metabolite separation [35] | UPLC-MS analysis | 1.8 μm, 2.1 × 100 mm; suitable for diverse metabolite classes |

| PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix | qRT-PCR validation [35] | Gene expression verification | Compatible with standard thermal cyclers, high sensitivity |

| SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis | cDNA synthesis [35] | RNA-seq library preparation | High efficiency reverse transcription for degraded samples |

| Quality Control Samples | Inter-batch normalization [31] | All omics platforms | Pooled reference samples for technical variance assessment |

| Pathway Databases (OncoboxPD) | Pathway topology information [33] | SPIA analysis | 51,672 uniformly processed human molecular pathways |

Advanced Integration Algorithms

Pathway Activation Level Calculation [33]:

The fundamental algorithm for calculating pathway activation levels (PALs) using the Signaling Pathway Impact Analysis (SPIA) method involves:

Perturbation Factor Calculation:

Where:

- PF(g) is the perturbation factor for gene g

- ΔE(g) is the normalized expression change of gene g

- β(g,u) represents the interaction between genes g and u

- Nds(u) is the number of downstream genes of u

Pathway Accumulation Calculation:

Where:

- Acc is the accuracy vector representing pathway perturbation

- B is the adjacency matrix representing pathway topology

- I is the identity matrix

- ΔE is the vector of expression changes

Multi-Omics Data Fusion Methods [31]:

- Tensor Factorization: Handles multi-dimensional omics data by decomposing complex datasets into interpretable components

- Network Propagation: Leverages known biological relationships to guide multi-omics analysis using protein-protein interaction networks

- Multi-Modal Deep Learning: Autoencoders and neural networks that automatically learn complex patterns across omics layers

- Graph Neural Networks: Explicitly model molecular interaction networks for superior biomarker discovery performance

Applications in Plant Biosystems Design

The integration of multi-omics approaches has transformed plant biosystems design by enabling [18] [34]:

- Predictive Model Development: Shifting from trial-and-error to model-driven genetic improvement

- Stress Resilience Engineering: Identifying key regulatory modules and metabolic signatures associated with abiotic stress tolerance

- Metabolic Pathway Optimization: Enhancing nutritional quality and medicinal compound production in plants

- Crop Improvement: Accelerating development of climate-resilient crops through systems-level understanding

In plant responses to abiotic stresses, integrated transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses have revealed sophisticated adaptive strategies involving transcriptional reprogramming and metabolic remodeling. These approaches have identified key genes and metabolic pathways involved in thermal, saline, water deficit, and heavy metal stress responses, providing crucial insights for designing stress-resilient crops [34].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental principle behind constraint-based modeling in metabolic engineering? Constraint-based modeling (CBM) is based on the principle of mass balance in a metabolic network under a quasi-steady state assumption. It represents the metabolism using a stoichiometric matrix (S), where the product of this matrix and the vector of metabolic fluxes (v) equals zero (S·v = 0). Thermodynamic and enzymatic capacity constraints are applied by setting upper and lower bounds on individual fluxes. This approach allows for the prediction of cellular behavior, such as growth or metabolite production, without requiring detailed kinetic parameters, making it suitable for genome-scale analysis [36].

Q2: How does a strain design algorithm like OptKnock identify gene deletion targets? Algorithms like OptKnock use computational simulation and mathematical optimization on genome-scale metabolic models (GSMMs) to propose gene deletions. They formulate a bi-level optimization problem where the outer objective is to maximize a desired product flux, and the inner objective is typically to maximize cellular growth (as a surrogate for biological fitness). The solution pinpoints a set of gene deletions that constrains the metabolic network in a way that forces the cell, in striving for optimal growth, to overproduce the target chemical [36].

Q3: My model predictions do not match experimental results in my plant system. What could be wrong? Discrepancies between in silico predictions and in vivo results are common and can arise from several sources [36]:

- Incomplete Model: The genome-scale metabolic reconstruction may lack critical pathways or regulatory loops present in the actual organism.

- Incorrect Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) Associations: The Boolean logic linking genes to reactions may be inaccurate or oversimplified, failing to capture complex isoenzyme interactions or post-translational regulation.

- Inaccurate Constraints: The flux constraints (αi and βi) applied to reactions may not reflect the in vivo enzymatic capacity or thermodynamic conditions.

- Context-Specificity: A generic model may not accurately represent the metabolic state of your specific cell type, tissue, or experimental condition.

Q4: What is the role of Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) associations in these models? GPR associations explicitly link genes to metabolic reactions using Boolean logic (e.g., "and" for protein complexes, "or" for isoenzymes). They are crucial for translating a set of gene deletions into the specific set of metabolic reactions that are inactivated in the model, thereby enabling more realistic predictions of phenotypic outcomes following genetic modifications [36].

Q5: Why is a node graph architecture suitable for representing and analyzing these metabolic networks? A node graph architecture is highly suitable because it directly mirrors the structure of metabolic networks. In this representation, metabolic reactions and/or metabolites can be modeled as nodes, and the metabolic fluxes between them are the links. This architecture allows for intuitive visual programming and manipulation of the network, facilitates the analysis of network properties (like modularity and hierarchy), and enables complex tasks to be broken down into atomic functional units, making it easier to understand and design metabolic pathways [37].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor or Unexpected Product Yield After Implementing a Predicted Gene Deletion Strategy

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low product titer, normal growth | Model may not account for all regulatory mechanisms or unknown bypass pathways. | Perform transcriptomic analysis to identify unexpected gene expression changes and refine the model accordingly. |

| Low product titer, poor growth | Deletion may have disrupted essential cofactor balances or created metabolic bottlenecks. | Check energy and redox balances (ATP, NADH, NADPH). Consider adaptive laboratory evolution to restore growth while maintaining production. |

| No product formation | Incorrect GPR association; the intended reaction was not successfully knocked out. | Verify the genetic modification (e.g., via sequencing) and confirm the GPR logic in the model accurately reflects the organism's genetics [36]. |

Problem: Computational Model is Intractable or Fails to Find a Solution

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|