Orthogroup Analysis in Plants: Evolutionary Insights, Methods, and Applications in Gene Family Research

Orthogroup analysis has become a cornerstone of comparative genomics, providing a robust framework for understanding gene family evolution, functional diversification, and adaptive processes in plants.

Orthogroup Analysis in Plants: Evolutionary Insights, Methods, and Applications in Gene Family Research

Abstract

Orthogroup analysis has become a cornerstone of comparative genomics, providing a robust framework for understanding gene family evolution, functional diversification, and adaptive processes in plants. This article explores the foundational concepts of orthogroup analysis, detailing how it distinguishes evolutionary relationships through speciation (orthologs) and duplication (paralogs). We examine state-of-the-art methodologies and tools, including OrthoFinder for orthogroup inference and synteny analysis for evolutionary context. The content addresses common analytical challenges and optimization strategies for complex gene families, particularly those with domain rearrangements and alternative splicing. Through case studies across diverse plant lineages—from stress-responsive glycosyltransferases to disease-resistant NBS genes—we demonstrate how orthogroup analysis facilitates functional gene validation and reveals evolutionary patterns driving plant adaptation. This comprehensive resource equips researchers with practical knowledge to design and implement orthogroup studies, accelerating discovery in plant evolutionary genomics and molecular breeding.

The Evolutionary Framework: Understanding Orthogroups, Paralogy, and Gene Family Diversification in Plants

In comparative genomics, the accurate classification of gene relationships is fundamental to understanding evolutionary processes and biological function. Homology, defined as the state of biological features (including genes and their products) descending from a common ancestor, forms the bedrock of this classification [1]. Homologous genes arise through two principal evolutionary mechanisms: the separation of populations during speciation events, and gene duplication within lineages. These distinct evolutionary paths give rise to orthologs and paralogs, respectively [1] [2]. The precise delineation of these relationships is not merely an academic exercise; it is crucial for reliable functional annotation, robust phylogenetic reconstruction, and insightful comparative genomics [3]. This framework is particularly relevant for plant evolutionary studies, where complex genomes, frequent whole-genome duplication events, and the evolution of specialized metabolic pathways demand rigorous analytical approaches. The emerging field of orthogroup analysis—the clustering of genes into groups descended from a single ancestral gene in a specified ancestor—provides a powerful framework for scaling these analyses across multiple genomes, enabling systematic investigation of gene family evolution in plants [3].

Core Concepts: Orthologs, Paralogs, and Orthogroups

Definitions and Evolutionary Origins

The terms ortholog and paralog were introduced by Walter Fitch to distinguish between two fundamentally distinct modes of descent from a common ancestral gene [3]. Orthologs (from the Greek "ortho," meaning "exact") are genes in different species that originate from a single gene in the last common ancestor of those species [4]. They diverge primarily through the process of speciation. In contrast, paralogs (from the Greek "para," meaning "beside") are genes related through duplication events within a single genome [1] [2]. All orthologs and paralogs are, by definition, homologs, as they share common ancestry.

Table 1: Key Concepts in Homologous Gene Classification

| Term | Definition | Evolutionary Mechanism | Functional Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Homolog | A gene descended from a common ancestral gene. | Any evolutionary divergence from a common ancestor. | Shared ancestry, but function may diverge. |

| Ortholog | Genes in different species that diverged via a speciation event [1] [2]. | Speciation. | Often retain equivalent biological functions across species [3]. |

| Paralog | Genes that diverged via a gene duplication event [1] [2]. | Gene Duplication. | Often evolve new, related, or specialized functions (neofunctionalization or subfunctionalization) [3]. |

| In-paralog | Paralogs that arose from a duplication event after a given speciation event [3] [4]. | Post-speciation duplication. | Considered co-orthologs; are bona fide orthologs relative to the pre-duplication gene. |

| Out-paralog | Paralogs that arose from a duplication event before a given speciation event [3] [4]. | Pre-speciation duplication. | Can be confused with true orthologs in pairwise comparisons. |

| Orthogroup | A set of genes all descended from a single ancestral gene in a specified reference ancestor [3]. | Combination of speciation and duplication. | A practical unit for comparative genomics across multiple species. |

The classification becomes more nuanced when considering multiple species or complex gene families. The concepts of in-paralogs and out-paralogs are critical for resolving these complexities. When analyzing orthology between two species, in-paralogs are paralogs that duplicated after the speciation event separating the two species, while out-paralogs duplicated before that event [4]. Consequently, in-paralogs are considered co-orthologs; for example, if a gene in Species A duplicates after diverging from Species B, both resulting genes in Species A are orthologous to the single gene in Species B, creating a one-to-many orthologous relationship [3].

The Orthology Conjecture and Its Implications for Function

A cornerstone of comparative genomics is the "orthology function conjecture," which posits that orthologous genes are most likely to retain equivalent (biologically interchangeable) functions in different organisms [3]. This principle underpins the transfer of functional annotations from well-characterized model organisms (e.g., Arabidopsis thaliana) to less-studied species. Paralogs, on the other hand, are more likely to diverge in function following duplication, a process driven by relaxed selective pressure on one copy, which can then acquire novel functions (neofunctionalization) or partition ancestral functions (subfunctionalization) [2] [3]. While this is a powerful general trend, exceptions exist, and caution is warranted, as functional divergence can occur even between orthologs over long evolutionary timescales.

Practical Protocols for Orthology Inference

Accurately inferring orthologs and paralogs is a central task in bioinformatics. Several computational approaches have been developed, ranging from pairwise comparisons to complex phylogenomic methods.

Protocol 1: The INPARANOID Algorithm for Pairwise Orthology Detection

The INPARANOID algorithm is a fully automatic method designed to find orthologs and in-paralogs between two species [4]. It was developed to address the challenge of distinguishing true orthologs from out-paralogs, which can be confounded in simple similarity searches.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Orthology Analysis

| Tool/Method | Primary Function | Key Inputs | Key Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|

| INPARANOID | Detects orthologs and in-paralogs between two species [4]. | Protein sequences from two genomes. | Clusters of orthologs and in-paralogs with confidence scores. |

| DomClust | Hierarchical clustering for ortholog grouping across multiple genomes, with domain detection [5]. | All-against-all pairwise protein sequence similarities. | Orthologous groups, with proteins split into domains if required. |

| BLASTP | Finds locally similar sequences in protein databases [5]. | A query protein sequence and a target protein database. | A list of similar sequences with alignment statistics (E-value, score). |

| Bidirectional Best Hit (BBH) | The conventional pairwise ortholog detection method. | Protein sequences from two genomes. | A list of putative ortholog pairs. |

Detailed Methodology:

- Input: The complete sets of protein sequences from two species.

- All-vs-All Sequence Similarity: Perform an all-against-all BLASTP search between the two proteomes. Significant matches are typically filtered by an E-value threshold (e.g., ≤ 0.001) [5].

- Seed Ortholog Pairs: Identify "two-way best hits" or "bidirectional best hits" (BBH). A pair of genes (A in Species 1, B in Species 2) is a BBH if A is the best hit of B in Species 1, and B is the best hit of A in Species 2. These high-confidence pairs seed the ortholog clusters.

- Add In-paralogs: For each seed ortholog cluster (A, B), the algorithm scans the proteome of each species to identify additional in-paralogs. A gene in Species 1 is added as an in-paralog to the cluster if it is more similar to the seed gene A than to any gene in Species 2, and vice-versa. This step expands one-to-one ortholog pairs into clusters that may contain multiple co-orthologs.

- Confidence Scoring: The method assigns confidence values for both orthologs and in-paralogs, providing a measure of reliability for the inferences.

- Output: Ortholog clusters between the two species, each containing a main ortholog pair and optionally, in-paralogs with confidence values.

Advantages: INPARANOID is fully automated, bypasses the computationally intensive steps of multiple sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree construction, and effectively separates in-paralogs from out-paralogs [4].

Protocol 2: The DomClust Algorithm for Multi-Genome Ortholog Grouping

For comparisons involving more than two genomes, clustering methods are required. The DomClust algorithm is a hierarchical clustering method that is effective for comparing many genomes simultaneously and can handle domain fusion and fission events [5].

Detailed Methodology:

- Input Preparation: Compute an all-against-all pairwise protein sequence comparison for all genes in all target genomes. The input for each pair includes a similarity score and the beginning and ending positions of the aligned segments.

- Construct Similarity Graph: Build a graph where vertices are protein sequences and edges represent significant homologous relationships, weighted by the similarity score.

- Hierarchical Clustering with gUPGMA: Perform a graph-based version of the Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic Averages (UPGMA). The process is a successive contraction of the similarity graph: a. Identify the edge with the best similarity score. b. Merge the two connected vertices (clusters) into a new vertex. c. Update the similarity scores between the new cluster and all other connected clusters using a group-average function. d. Repeat until the best similarity score falls below a predefined cutoff.

- Domain Splitting: During clustering, the algorithm checks for domain fusion or fission events. When two sequences (or clusters) are merged based on a local alignment, the procedure can split the merged vertex into segments representing the aligned region and the left/right overhangs. This ensures that orthologous groups are defined at the domain level when necessary, which is crucial for accuracy [5].

- Orthologous Group Formation: The final result of the hierarchical clustering is a set of trees. These trees are then processed to ensure that intra-species paralogous genes are divided into different groups, resulting in plausible orthologous groups (orthogroups) [5].

Advantages: DomClust is efficient for large-scale analyses, explicitly handles complex domain architectures, and has been shown to produce classifications that agree well with curated databases like COG [5].

Application in Plant Evolutionary Studies: A Case Study on Moonseed

The inference of orthologs and paralogs is particularly powerful for unraveling the evolutionary history of specific traits in plants. A recent groundbreaking study on Canadian moonseed (Menispermum canadense) provides an exemplary case of "molecular archaeology" [6]. Researchers sought to understand how this plant evolved the rare ability to produce a halogenated compound, acutumine, which has potential medicinal properties for targeting leukemia cells and regulating neurological receptors.

Experimental Workflow and Findings:

- Genome Sequencing and Gene Family Identification: The researchers first sequenced the entire moonseed genome, providing a genetic map for their investigation [6].

- Tracing Evolutionary History: Using the genomic data, they traced the ancestry of a key enzyme, dechloroacutumine halogenase (DAH), which is responsible for the unique chlorination reaction. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that DAH did not appear de novo but evolved from a much more common enzyme, flavonol synthase (FLS), which is involved in flavonoid biosynthesis [6].

- Reconstructing the Evolutionary Path: The analysis showed that over hundreds of millions of years, the moonseed lineage underwent a series of gene duplications, losses, and mutations. The evolutionary path from FLS to DAH was not direct but involved several non-functional intermediate genes, described as "evolutionary relics" [6].

- Experimental Validation: To confirm their evolutionary inference, the team reconstructed ancestral enzymes in the laboratory. By introducing specific mutations into the ancestral FLS-like gene, they were able to recover a small percentage (1-2%) of the halogenase activity, validating that the identified evolutionary path could indeed lead to the new function [6].

This case study underscores the hierarchical nature of orthology and paralogy. The FLS and DAH genes are paralogs, having diverged via a duplication event in an ancestral plant. However, within the moonseed lineage, the series of duplications that eventually gave rise to DAH created in-paralogs relative to key speciation events. Defining the correct orthologous groups at different evolutionary depths was essential for reconstructing this complex narrative.

The precise definitions of orthologs, paralogs, and orthogroups are more than semantic distinctions; they are fundamental concepts that guide the methodology and interpretation of evolutionary studies. As demonstrated by the moonseed example, correctly applying these concepts allows researchers to trace the complex evolutionary pathways that give rise to new genes and functions. For plant genomics, where polyploidy and frequent gene duplication are common, robust orthology inference methods like INPARANOID and DomClust are indispensable tools. They enable the identification of conserved gene families, the prediction of gene function in non-model species, and the reconstruction of the evolutionary events that have shaped the remarkable diversity of plant form and function. The ongoing development of more efficient and accurate algorithms for orthogroup analysis, particularly those capable of handling hundreds or thousands of bacterial genomes, promises to further enhance our ability to conduct comparative genomic studies at an unprecedented scale [7].

Application Note

This Application Note provides a consolidated overview of the impact and analysis of major gene duplication events—Whole Genome Duplication (WGD), Tandem Duplication (TD), and Segmental Duplication (SD)—within the context of plant evolutionary genomics and orthogroup analysis. It is intended for researchers investigating how these events drive functional innovation, adaptive evolution, and genome complexity.

Systematic genomic analysis across diverse plant species reveals distinct patterns of occurrence, retention, and evolutionary pressure for each duplication type.

Table 1: Characteristics of Major Gene Duplication Types in Plants

| Duplication Type | Scale & Mechanism | Frequency & Retention | Primary Evolutionary Signatures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Genome Duplication (WGD) | Duplication of the entire genome; often episodic [8]. | Duplicate genes decrease exponentially with event age; high initial retention followed by fractionation [8]. | Strong purifying selection; genes often retain core, dosage-sensitive functions; central hubs in co-expression networks [9] [8]. |

| Tandem Duplication (TD) | Duplication of a single gene or cluster via unequal crossing-over, creating adjacent copies [8]. | High and continuous frequency over time; shows no significant decrease with age, providing a constant supply of variation [8]. | Undergoes rapid functional divergence and strong selective pressure; enriched in environment-responsive genes (e.g., defense, stress) [10] [8] [11]. |

| Segmental Duplication (SD) | Duplication of a large chromosomal segment (>1 kb) through NAHR or replication errors [12]. | In humans, ~7% of the genome; shows significant polymorphism and copy-number variation in populations [12]. | Major source of copy-number polymorphic genes; linked to disease, adaptation, and evolution of novel traits (e.g., brain development, diet) [12]. |

| Proximal Duplication (PD) | Duplication of genes separated by a few intervening genes (<10) [8]. | Frequency shows no significant decrease over time, similar to TD [8]. | Experiences strong selective pressure, similar to TD; functional roles often biased toward plant self-defense [8]. |

| Transposed Duplication (TRD) | Relocation of a gene copy to a new genomic position via DNA- or RNA-based mechanisms [8]. | Duplicate genes decline over time, parallel to WGD and Dispersed Duplication [8]. | Expression divergence can occur via "compensatory drift" rather than preserved regulatory elements [9]. |

Functional and Evolutionary Consequences

Gene duplication acts as a primary source of raw genetic material for evolutionary innovation. The fates of duplicated genes are diverse and have distinct functional outcomes:

- Neofunctionalization: One copy acquires a novel function while the other retains the original. This is a key pathway for adaptive evolution, as seen in metallocarboxypeptidase (CPO) paralogs that evolved new substrate specificities [13].

- Subfunctionalization: The ancestral functions are partitioned between the duplicates. This can occur spatially, as revealed by spatial transcriptomics showing paralogs specializing in expression across different cell types [9].

- Gene Dosage and Balance: WGD retains duplicates involved in multiprotein complexes due to dosage-balance constraints, while TD can directly increase the dosage of specific gene products [9] [10].

- Adaptive Evolution: Lineage-Specific Expansions (LSEs) of gene families show significantly stronger signals of positive selection compared to single-copy genes. For example, in angiosperms, LSE genes were found to have codons under positive selection, whereas single-copy genes showed none [11].

Protocols

This section outlines a standard workflow for identifying and classifying gene duplication events from genomic data, which is fundamental for orthogroup analysis in evolutionary studies.

Protocol: Identification and Classification of Gene Duplication Events

Objective: To identify orthologs and paralogs from multiple genome assemblies, reconstruct phylogenetic relationships, and systematically classify gene duplication events.

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item/Tool Name | Function/Application | Specification/Note |

|---|---|---|

| OrthoFinder | Infers orthogroups and gene families from protein sequences across multiple species [14]. | Uses graph-based algorithm; outputs orthogroups, gene trees, and a rooted species tree [14]. |

| GENESPACE | Analyzes genome-wide synteny and identifies conserved gene blocks [14]. | Requires annotation files in BED format; works with OrthoFinder output. |

| DupGen_finder | Classifies duplicated genes into different categories (WGD, TD, SD, etc.) [8]. | A specialized pipeline that integrates synteny and phylogenomic data [8]. |

| BUSCO | Assesses the completeness of genome assemblies and annotations. | Benchmarks against universal single-copy ortholog sets. |

| Multiple Genome Assemblies | The primary data source for comparative analysis. | Requires high-quality, chromosome-level assemblies for accurate synteny analysis [12]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Data Acquisition and Pre-processing

- Obtain genome assemblies and their structural annotations (GFF/GTF format) from public databases (e.g., NCBI, Darwin Tree of Life).

- Use a script (e.g.,

primary_transcript.pyfrom OrthoFinder) to filter the annotations, retaining only the longest protein-coding transcript for each gene to avoid isoform redundancy [14]. - Validate genome assembly completeness using BUSCO against a relevant lineage-specific dataset (e.g.,

viridiplantae_odb10for plants) [14].

Orthogroup Inference

- Run OrthoFinder using the filtered protein sequences from all species as input.

- OrthoFinder will perform an all-vs-all BLAST, infer orthogroups, and resolve the gene relationships. The output includes:

- A statistics file showing the number of orthogroups.

- A list of genes per orthogroup.

- A rooted species tree inferred from single-copy orthologs [14].

Synteny and Microsynteny Analysis

- Convert annotation files from GFF to BED format for use with GENESPACE.

- Run GENESPACE using the OrthoFinder results and the BED files as input to identify syntenic blocks across genomes. This helps delineate regions with conserved gene order, which is crucial for identifying WGD and segmental duplications [14].

Phylogenetic Reconstruction and Dating

- Use the species tree generated by OrthoFinder, which is based on a concatenated multiple sequence alignment of single-copy orthologs.

- To date duplication events, calculate the synonymous substitution rate (Ks) for paralogous pairs within syntenic blocks. The distribution of Ks values (e.g., plotted as histograms fitted with Gaussian Mixture Models) can reveal peaks corresponding to past WGD events [8].

Systematic Classification of Duplications

- Run DupGen_finder or a similar pipeline to classify duplicated genes identified in the previous steps. The tool uses synteny information and phylogenetic relationships to categorize gene pairs as follows [8]:

- WGD-derived: Paralogous pairs located within syntenic blocks.

- Tandem Duplication (TD): Paralogous pairs adjacent or in close proximity on the same chromosome with no intervening non-homologous genes.

- Segmental Duplication (SD): Duplicated segments that are interspersed (separated by >1 Mb) or mapped to non-homologous chromosomes [12].

- Other types (Proximal, Transposed, Dispersed) are also classified based on specific criteria.

- Run DupGen_finder or a similar pipeline to classify duplicated genes identified in the previous steps. The tool uses synteny information and phylogenetic relationships to categorize gene pairs as follows [8]:

Protocol: Analyzing Expression Divergence of Duplicates

Objective: To investigate the functional divergence of duplicated gene pairs using spatial or tissue-specific transcriptomic data.

Procedure Notes

- Data Integration: Align RNA-seq reads from different tissues, cell types (using spatial transcriptomics for high resolution), or experimental conditions to the reference genome or transcriptome [9].

- Expression Quantification: Calculate normalized expression values (e.g., TPM) for each gene in each sample.

- Divergence Metrics: Quantify expression divergence between paralogs using metrics like Pearson correlation or Euclidean distance based on their expression profiles.

- Interpretation: Pairs with highly correlated expression across most cell types may indicate functional redundancy or selection for dosage. Pairs with divergent, tissue- or cell-type-specific expression are strong candidates for subfunctionalization or neofunctionalization [9] [10].

Tracing Lineage-Specific Expansions and Contractions in Plant Gene Families

Lineage-specific expansions and contractions of gene families represent a fundamental mechanism driving evolutionary adaptation and functional diversification in plants. These dynamic changes in gene content are powerful signatures of selective pressures that shape the genetic architecture of plant lineages, influencing traits from metabolic pathways to defense mechanisms. This application note provides a structured framework for identifying and analyzing these evolutionary patterns through orthogroup analysis, integrating computational genomics with experimental validation. We detail protocols for comparative genomic studies and present essential tools and reagents that empower researchers to investigate how gene family dynamics contribute to plant evolution, specialization, and environmental adaptation.

The evolutionary history of plant genes is characterized by continuous processes of duplication, divergence, and loss, leading to the formation of gene families of varying sizes and complexities. Orthologous genes—those related by speciation events—typically retain equivalent biological functions across different species, while paralogous genes—related by duplication events—often diverge in function [3]. This functional divergence makes paralogues a primary source of evolutionary innovation.

Lineage-specific expansions occur when particular gene families undergo significant duplication in a specific lineage, often conferring adaptive advantages. For instance, in the genus Colletotrichum, broad host-range pathogens exhibit expansions of gene families encoding carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes) and proteases, whereas narrow host-range species show contractions in these same families [15]. Conversely, contractions may indicate functional redundancy or specialization. Understanding these patterns requires robust methods for orthology assignment and comparative analysis across multiple genomes.

Computational Workflow for Orthogroup Analysis

Orthology Inference and Gene Family Definition

The foundation of gene family evolution analysis lies in accurate orthology inference. Orthologous groups (orthogroups) represent sets of genes descended from a single ancestral gene in a specified reference ancestor [3]. The following protocol outlines a standard workflow for orthogroup construction and analysis:

- Data Acquisition: Obtain proteome or coding sequence (CDS) data for target species using resources like the

biomartrR package, which facilitates reproducible retrieval of genomic data [16]. - Orthology Inference: Employ tools such as the

orthologrR package to perform large-scale comparative genomics. This package supports multiple orthology inference methods, including Reciprocal Best Hit (RBH) and other advanced algorithms [16]. - Orthogroup Delineation: Use clustering algorithms (e.g., OrthoFinder) to group genes into orthogroups across all analyzed species.

- Evolutionary Analysis: Identify significantly expanded or contracted gene families using tools like CAFE (Computational Analysis of gene Family Evolution), which models gene family gains and losses across a phylogenetic tree.

Table 1: Key Software Tools for Orthogroup Analysis

| Tool/Package | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

orthologr R package |

Orthology inference and dN/dS estimation | Comparative genomics across multiple species [16] |

biomartr R package |

Genomic data retrieval | Automated download of genomes, proteomes, and CDS [16] |

| CAFE | Gene family evolution analysis | Statistical detection of significant expansions/contractions |

| Phylogenetic Software | (e.g., MrBayes, RAxML) | Species tree reconstruction for evolutionary context [15] |

Analyzing Sequence Evolution and Selection Pressures

Beyond changes in gene copy number, analyzing selection pressures on coding sequences provides insights into functional constraints and adaptive evolution. The orthologr package implements several methods for estimating the ratio of non-synonymous (dN) to synonymous (dS) substitutions:

Table 2: Selection Pressure Interpretation via dN/dS Values

| dN/dS Value | Interpretation | Evolutionary Implication |

|---|---|---|

| dN/dS > 1 | Positive selection | Diversifying selection, potentially driving functional innovation |

| dN/dS ≈ 1 | Neutral evolution | No selective constraints, rare in functional coding sequences |

| dN/dS < 1 | Purifying selection | Conservation of function, removal of deleterious mutations |

Workflow Visualization

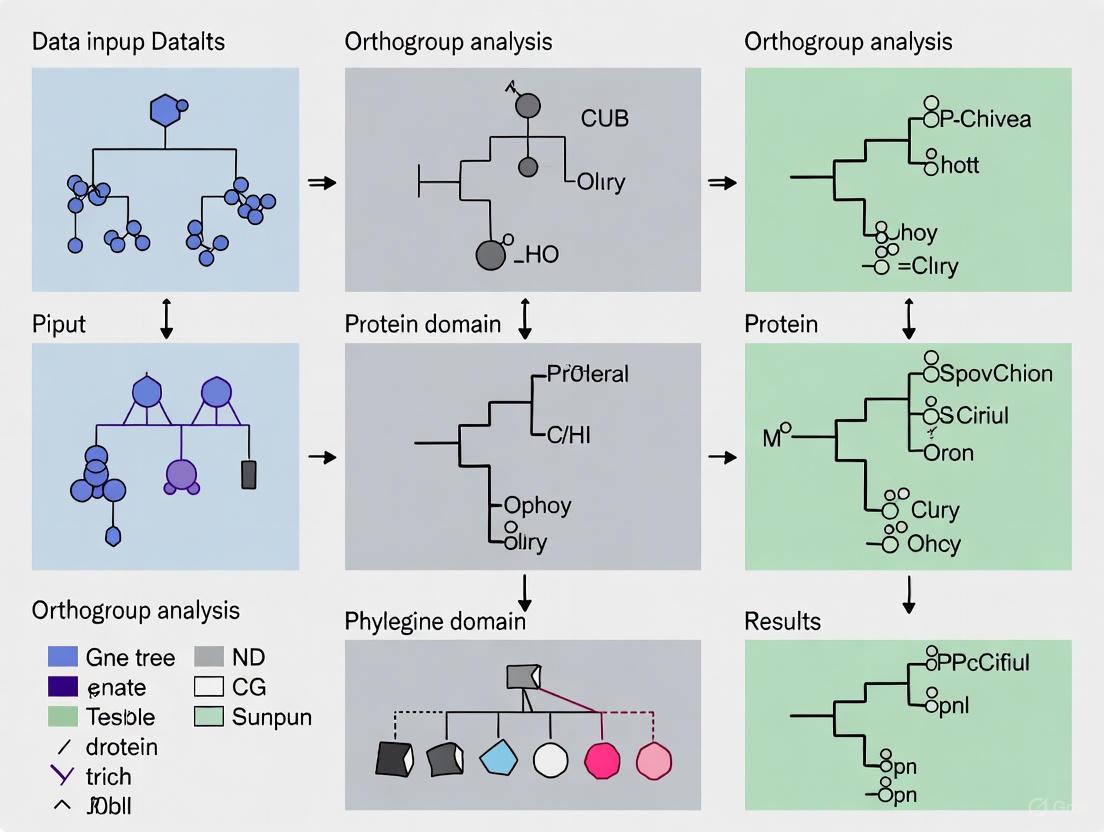

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational and experimental workflow for analyzing gene family evolution:

Experimental Validation and Functional Characterization

Computational predictions of gene family expansions and contractions require experimental validation to confirm biological significance. The following protocols enable researchers to test hypotheses generated from genomic analyses.

Transient Transformation for Protein Localization

Biolistic transformation provides a rapid method for visualizing protein localization and interactions in plant systems, complementing stable transformation approaches. This technique is particularly valuable for species where stable transformation is challenging or time-consuming.

Protocol: Biolistic Transformation of Plant Epidermal Cells

Materials:

- Gold microcarriers (1 μm diameter)

- Particle delivery system (e.g., PDS-1000/He)

- Expression vectors with fluorescent protein fusions

- Plant materials (e.g., thalli, leaves)

- 0.1 M Spermidine

- Ethanol (70% and 100% solutions)

Method:

- Plant Preparation: Grow plants under controlled conditions. For liverworts like Marchantia polymorpha, maintain on Johnson's growth medium in Petri dishes sealed with micropore tape [17].

- Microcarrier Preparation: Coat 1 μm gold microcarriers with plasmid DNA encoding your gene of interest fused to a fluorescent marker, using spermidine as a binding agent.

- Bombardment: Place plant tissue in the gene gun chamber and bombard using appropriate pressure and vacuum settings (e.g., 1,100 psi rupture discs for Marchantia).

- Incubation: Incubate bombarded tissues under normal growth conditions for 12-48 hours to allow for transgene expression.

- Visualization: Image transformed cells using confocal laser scanning microscopy to determine subcellular localization of fluorescent fusion proteins.

Application: This protocol enables rapid functional characterization of genes identified in lineage-specific expansions. For example, it can be used to test whether duplicated genes have acquired new subcellular localizations, suggesting functional diversification [17].

Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation (BiFC)

BiFC allows for the detection of protein-protein interactions in living plant cells, providing insights into functional relationships between duplicated genes.

Protocol: Testing Protein Interactions with BiFC

Materials:

- Split-YFP (or other fluorescent protein) vectors

- Biolistic transformation equipment

- Confocal microscope

Method:

- Clone genes of interest into appropriate BiFC vectors as fusions to complementary halves of a fluorescent protein.

- Co-transform plant tissues with both constructs via biolistics.

- Incubate for 24-48 hours to allow for protein expression and potential reconstitution of the fluorescent protein.

- Visualize using fluorescence microscopy; fluorescence emission indicates interaction between the tested protein pairs.

Application: BiFC is particularly valuable for testing whether paralogues from expanded gene families have maintained or diverged in their interaction partners, providing evidence for functional conservation or neofunctionalization [17].

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful analysis of gene family evolution relies on a combination of bioinformatic tools and experimental reagents. The following table catalogs essential resources for plant evolutionary genomics studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Plant Gene Family Studies

| Category | Specific Resource | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Tools | orthologr R package [16] |

Orthology inference and dN/dS estimation between genomes |

biomartr R package [16] |

Programmatic retrieval of genomic data from public databases | |

| Marchantia genome database [17] | Species-specific genomic information and BLAST services | |

| Experimental Materials | Gold microcarriers (1 μm) [17] | DNA coating and delivery in biolistic transformations |

| Fluorescent protein markers [17] | Tagging proteins for localization and interaction studies | |

| Gateway-compatible vectors [17] | Modular cloning system for efficient construct generation | |

| Staining & Visualization | FM4-64 dye [17] | Staining of endocytic compartments and plasma membranes |

| DAPI stain [17] | Nuclear counterstaining for cellular localization studies | |

| Propidium Iodide (PI) [17] | Cell wall staining for contextualizing cellular architecture |

Case Studies in Plant Gene Family Evolution

Metabolic Pathway Diversification in Oenothera

Comparative transcriptomics across 29 species of the evening primrose genus (Oenothera) revealed extensive heterogeneity in gene family evolution, with section Oenothera exhibiting particularly pronounced evolutionary changes [18]. Analysis of phenolic metabolism genes identified 1,568 phenolic genes arranged into 83 multigene families that varied substantially across the genus. The evolution of these families was characterized by a rapid genomic turnover, with 33 gene families undergoing large expansions, gaining approximately twice as many genes as they lost [18]. Upstream enzymes in the phenylpropanoid pathway—phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) and 4-coumaroyl:CoA ligase (4CL)—accounted for the majority of significant expansions and contractions, highlighting their pivotal role in the evolutionary diversification of specialized metabolism in this genus.

Host Range Adaptation in Colletotrichum Pathogens

Comparative genomics of fungal pathogens in the Colletotrichum acutatum species complex (CAsc) demonstrated a clear association between gene family dynamics and host adaptation [15]. Lineage-specific expansions of carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes) and protease-encoding genes were identified in broad host-range pathogens, whereas narrow host-range species exhibited contractions in these gene families [15]. Additionally, researchers discovered a lineage-specific expansion of necrosis and ethylene-inducing peptide 1 (Nep1)-like protein (NLPs) families within the CAsc. These genomic changes likely enhance the ability of generalist pathogens to degrade various plant cell walls and manipulate host physiology, illustrating how gene family expansions can facilitate adaptation to diverse ecological niches.

The integrated computational and experimental framework presented here provides a comprehensive approach for tracing lineage-specific expansions and contractions in plant gene families. Orthogroup analysis serves as the computational foundation for detecting these evolutionary patterns, while emerging technologies in transient transformation and protein interaction assays enable functional validation of genomic predictions. As genomic resources continue to expand across the plant kingdom, these methods will become increasingly powerful for uncovering the genetic basis of plant adaptation and diversification. The case studies in Oenothera and Colletotrichum illustrate how this approach can reveal fundamental insights into the evolution of metabolic diversity and host-pathogen interactions, with broad implications for plant biology, agriculture, and biotechnology.

Application Note

This document provides a detailed exploration of the diversification patterns observed in two critical plant gene families: the nucleotide-binding site (NBS) family, central to plant defense, and the glycosyltransferase family 8 (GT8), pivotal in plant metabolism. Framed within a broader thesis on orthogroup analysis, this note synthesizes current research to illustrate how evolutionary mechanisms shape gene family architecture and function, with direct implications for crop improvement and biotechnological applications.

The study of gene families has been revolutionized by the adoption of pangenomic perspectives and orthogroup-based analysis. Traditional studies relying on a single reference genome fail to capture the full gene repertoire of a species, missing important presence-absence variations (PAVs) [19]. An orthogroup is defined as a set of genes descended from a single gene in the last common ancestor of all species being considered, encompassing both orthologs and paralogs [20]. This framework allows for a more genuine reconstruction of evolutionary history.

A seminal study on the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) family in barley demonstrated the power of this approach, classifying 201 orthogroups into 140 core (present in all genomes), 12 softcore, 29 shell, and 20 cloud (line-specific) genes, revealing a complete profile previously unattainable with a single genome [19]. Macroevolutionary studies across 352 eukaryotic species reveal a common pattern where gene family content peaks at major evolutionary transitions and then gradually decreases towards extant organisms, a process likely driven by ecological specialization and functional outsourcing [21]. This paradigm shift provides the context for understanding the specific evolutionary trajectories of the NBS and GT8 families.

The NBS Gene Family: Diversification in Plant Defense

The NBS gene family constitutes the largest class of plant resistance (R) genes, encoding intracellular immune receptors that mediate effector-triggered immunity (ETI) [22]. A comprehensive analysis across 34 plant species identified 12,820 NBS-domain-containing genes, which were classified into 168 distinct domain architecture classes, revealing significant diversity from classical (e.g., TIR-NBS-LRR) to species-specific structural patterns [23].

Evolutionary Patterns and Duplication Mechanisms

Research on the ZmNBS family in maize within a 26-line pangenome revealed extensive Presence-Absence Variation (PAV), supporting a "core-adaptive" model of evolution. This distinguishes conserved "core" subgroups (e.g., ZmNBS31, ZmNBS17-19) from highly variable "adaptive" ones (e.g., ZmNBS1-10, ZmNBS43-60) [24]. Duplication mechanisms are subtype-specific:

- Canonical CNL/CN genes primarily originate from dispersed duplications.

- N-type genes are enriched in tandem duplications [24].

Selection pressures also vary by duplication mode. In maize, whole-genome duplication (WGD)-derived genes experience strong purifying selection (low Ka/Ks ratio), while genes from tandem and proximal duplications show signs of relaxed or positive selection, highlighting their role in neofunctionalization and adaptation [24]. This pattern is consistent in barley, where whole-genome/segmental duplications expand core bHLH genes, while dispensable genes more often result from small-scale duplications [19].

Table 1: Quantitative Overview of NBS Gene Family in Select Species

| Species | Total NBS Genes Identified | Typical NLRs (with complete N & LRR domains) | Notable Subfamily Expansions/Reductions | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maize (Zea mays) | Not Specified | Not Specified | "Core-adaptive" structure with extensive PAV; Core (e.g., ZmNBS31) vs. Adaptive (e.g., ZmNBS1-10) subgroups. | [24] |

| Salvia (Salvia miltiorrhiza) | 196 | 62 | Extreme reduction of TNL and RNL subfamilies; 61 CNLs, 1 RNL. | [22] |

| Barley (Hordeum vulgare) | 161-176 (across 20 genomes) | Classified into 201 OGGs | 140 core, 12 softcore, 29 shell, 20 cloud bHLHs identified via pangenome. | [19] |

| Multiple Species (34 species) | 12,820 | Various | 168 domain architecture classes identified; 603 orthogroups with core and unique OGs. | [23] |

Case Study: NBS Family inSalvia miltiorrhizaand Cotton

A genome-wide analysis of the medicinal plant Salvia miltiorrhiza identified 196 NBS genes, but only 62 were typical NLRs with complete N-terminal and LRR domains [22]. A striking finding was the marked degeneration of the TNL and RNL subfamilies, with only 2 TNLs and 1 RNL identified [22]. This reduction is a shared feature across the Salvia genus, suggesting a lineage-specific evolutionary trajectory [22].

In cotton, research on resistance to cotton leaf curl disease (CLCuD) compared tolerant (Mac7) and susceptible (Coker 312) accessions. Genetic variation analysis found 6,583 unique variants in the NBS genes of the tolerant Mac7 compared to 5,173 in the susceptible line [23]. Functional validation via Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) of a candidate gene (GaNBS from orthogroup OG2) demonstrated its role in reducing viral titer [23].

The GT8 Gene Family: Diversification in Plant Metabolism

The GT8 gene family encodes glycosyltransferases critical for the biosynthesis of plant cell wall polymers, including pectin and xylan, and also play roles in abiotic stress responses [25] [26] [27]. They are primarily classified into subfamilies involved in cell wall synthesis (GAUT, GATL) and those that are not (GolS, PGSIP) [27].

Genomic Composition and Functional Diversity

The number of GT8 members varies by species, as shown in the table below. Promoter analyses in both Eucalyptus grandis and tomato have revealed an abundance of hormone-responsive and stress-responsive cis-elements, indicating complex regulatory networks linking cell wall biosynthesis to environmental adaptation [25] [27].

Table 2: Quantitative Overview of GT8 Gene Family in Select Species

| Species | GT8 Members Identified | Subfamilies Identified | Key Proposed or Validated Functions | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eucalyptus grandis | 52 | GAUT, GATL, GolS, PGSIP | EgGUX02/EgGUX04 (GlcA incorporation in xylan); EgGAUT1/EgGAUT12 (xylan/pectin biosynthesis). | [25] [26] |

| Tomato (S. lycopersicum) | 40 | GAUT, GATL, GolS, PGSIP | SlGolS1 (validated role in cold stress tolerance via VIGS). | [27] |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | 41 | GAUT, GATL, GolS, PGSIP | AtGolS1/2 (drought/salt stress); AtGolS3 (cold stress); QUA1/GAUT1 (pectin biosynthesis). | [25] |

| Rice (O. sativa) | 40 | GAUT, GATL, GolS, PGSIP | OsGolS1 (salt stress); OsGAUT21, OsGATL2, OsGATL5 (cold stress). | [27] |

Case Study: GT8 Family inEucalyptus grandisand Tomato

In the woody plant Eucalyptus grandis, 52 GT8 members were identified and phylogenetically classified [25]. Genes were dispersed across all chromosomes except chromosomes 3 and 7. Phylogenetic inference suggested subfunctionalization, with specific members like EgGUX02 and EgGUX04 potentially mediating glucuronic acid incorporation into xylan, while EgGAUT1 and EgGAUT12 are likely direct contributors to xylan and pectin biosynthesis [25] [26].

In tomato, a study identified 40 SlGT8 genes [27]. Expression profiling under cold stress identified nine differentially expressed genes. Among them, SlGolS1 was functionally validated using VIGS, confirming its role in cold tolerance, likely through the accumulation of raffinose family oligosaccharides (RFOs) that act as osmoprotectants and antioxidants [27].

Experimental Protocols for Gene Family Analysis

Protocol 1: Genome-Wide Identification and Characterization of a Gene Family

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used in the cited studies for identifying NBS and GT8 genes [25] [23].

Gene Family Member Identification

- Retrieve Reference Sequences: Obtain the hidden Markov model (HMM) profile for the protein domain of interest (e.g., PF00931 for NBS, PF01501 for GT8) from the Pfam database.

- Genome Mining: Use tools like

PfamScan.plor HMMER to search the proteome of the target species against the HMM profile. An E-value cutoff (e.g., 1.1e-50 [23] or 1.0 [25]) is applied. - Complementary BLAST: Perform a BLASTP search using known protein sequences from a model organism (e.g., A. thaliana) against the target proteome as a complementary identification method [27].

- Final Candidate Set: Combine results from both methods, remove duplicates, and manually verify the presence of the defining domain(s).

Physicochemical and Structural Characterization

- Use tools like the ProtParam tool on Expasy to analyze molecular weight, theoretical isoelectric point (pI), and amino acid composition [25].

- Predict subcellular localization using tools like WoLF PSORT or TargetP.

- Annotate gene structures (exons/introns) and identify conserved motifs using MEME Suite.

Phylogenetic and Evolutionary Analysis

- Perform multiple sequence alignment of protein sequences using MAFFT or ClustalW.

- Construct a phylogenetic tree using Maximum Likelihood (e.g., with MEGA11 or FastTree) or Neighbor-Joining methods. Bootstrap analysis (e.g., 1000 replicates) should be used to assess node support [25] [23].

- Classify genes into subfamilies based on their clustering in the phylogenetic tree.

Protocol 2: Pangenome-Based Orthogroup Analysis

This protocol, inspired by the barley bHLH study, leverages pangenomics to overcome single-genome bias [19].

- Data Collection: Assemble a set of multiple high-quality genomes representing the diversity within a species.

- Orthogroup Inference: Use OrthoFinder (v2.2.6 or higher) with Diamond for sequence alignment to cluster predicted protein sequences from all genomes into orthogroups (OGs) [20] [19].

- Classify OGs by Dispensability:

- Core OGs: Present in all genomes.

- Softcore OGs: Missing in a very small number of genomes.

- Shell OGs: Present in a moderate number of genomes.

- Cloud OGs: Present in only a few genomes (line-specific) [19].

- Evolutionary Inference: Analyze duplication mechanisms (WGD vs. tandem) and selection pressure (Ka/Ks calculation) specific to each OG category to understand expansion and evolutionary constraints.

Protocol 3: Functional Validation via Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS)

This protocol summarizes the VIGS approach used to validate the function of SlGolS1 in tomato and GaNBS in cotton [23] [27].

- Vector Construction: Clone a 300-500 bp fragment of the candidate gene (e.g., SlGolS1) into a VIGS vector (e.g., Tobacco Rattle Virus-based pTRV2 vector).

- Plant Transformation: Transform agrobacterium strains with the recombinant vector (pTRV1 and pTRV2-SlGolS1) and infiltrate the agrobacterium mixture into the leaves of young tomato plants (e.g., at the two-true-leaf stage).

- Experimental Treatment: After giving the VIGS system time to silence the gene (e.g., 3-4 weeks), subject the silenced plants and control plants (infiltrated with empty pTRV2) to the relevant stress (e.g., cold stress at 4°C).

- Phenotypic and Molecular Analysis:

- Assess physiological and phenotypic changes (e.g., photosystem efficiency, membrane damage, growth).

- Quantify the silencing efficiency and expression of related genes using qRT-PCR.

- Measure relevant biochemical parameters (e.g., raffinose content for GolS, viral titer for NBS genes).

Visualization of Workflows and Pathways

Gene Family Identification and Orthogroup Analysis Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated bioinformatics pipeline for gene family analysis, from single-genome to pangenome scale.

NBS-Mediated Effector-Triggered Immunity (ETI) Signaling Pathway

This diagram outlines the simplified signaling pathway in NBS-LRR-mediated plant immunity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools and Reagents for Gene Family Studies

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| HMMER / PfamScan | Identifies protein domains in a sequence using Hidden Markov Models. | Initial identification of NBS (PF00931) or GT8 (PF01501) genes in a proteome [23]. |

| OrthoFinder | Infers orthogroups and gene families from multiple proteomes. | Clustering genes from a pangenome into core and dispensable orthogroups [19]. |

| DIAMOND | High-speed sequence aligner for BLAST-like searches. | Used within OrthoFinder for fast all-vs-all sequence comparisons [20] [23]. |

| TBtools-II | An integrative bioinformatics toolkit for big biological data. | Used for gene structure visualization, chromosome mapping, and synteny analysis [25]. |

| MEGA11 | Software for molecular evolutionary genetics analysis. | Constructing phylogenetic trees and evolutionary analysis [25]. |

| TRV-based VIGS Vectors | Virus-Induced Gene Silencing system for rapid functional validation. | Silencing SlGolS1 in tomato or GaNBS in cotton to test function in stress response [23] [27]. |

| Phytozome / TAIR | Public plant genomics databases for retrieving sequence data. | Source of reference genome sequences and annotations for A. thaliana, E. grandis, etc. [25]. |

This application note demonstrates how orthogroup analysis within a pangenomic framework reveals the intricate diversification patterns of plant gene families. The NBS family evolves rapidly through a "core-adaptive" model driven by specific duplication mechanisms and selective pressures, tailoring plant immunity. The GT8 family exhibits subfunctionalization, where different members are co-opted for distinct roles in cell wall biosynthesis and abiotic stress tolerance. The integration of bioinformatics protocols, functional validation techniques like VIGS, and the reagents outlined in this note provides a robust roadmap for researchers to dissect the evolution and function of gene families, ultimately enabling the strategic improvement of crop resilience and productivity.

From Data to Discovery: Practical Workflows for Orthogroup Inference and Multi-Omics Integration

In the field of plant evolutionary genomics, accurately identifying groups of homologous genes originating from a single ancestral gene in the last common ancestor—known as orthogroups—is a fundamental prerequisite for comparative studies [28]. These analyses provide the foundational framework for investigating gene family evolution, deciphering the genetic basis of adaptive traits, and understanding the evolutionary history of plant species [29]. The core bioinformatics pipeline comprising OrthoFinder, DIAMOND, and the Markov Cluster (MCL) algorithm has emerged as a powerful, integrated solution for this task, combining computational efficiency with high accuracy [30] [31]. When applied to plant genomes, which often exhibit complex histories of whole-genome duplications and subsequent gene loss, this pipeline enables researchers to systematically identify orthologous relationships across multiple species [32] [29]. For example, orthogroup analysis has been successfully deployed to study the evolution of desiccation tolerance in plants and to identify conserved cold-responsive transcription factors across eudicots [33] [20]. This application note details the experimental protocols, workflow visualization, and practical implementation of these core tools within the context of plant evolutionary genomics research.

Tool Performance and Benchmarking

Comparative Performance of Orthology Detection Methods

The accuracy and efficiency of orthology detection methods have been extensively benchmarked. OrthoFinder consistently demonstrates superior performance in independent evaluations. On standardized tests from the Quest for Orthologs (QfO) consortium, OrthoFinder achieved 3-24% higher accuracy on the SwissTree test and 2-30% higher accuracy on the TreeFam-A test compared to other methods [31]. A separate comprehensive assessment using Latent Class Analysis (LCA) to evaluate various orthology detection strategies applied to eukaryotic genomes revealed that most methods exhibit a fundamental trade-off between sensitivity and specificity [28]. BLAST-based methods typically achieve high sensitivity, while tree-based methods are characterized by high specificity [28]. Among the methods evaluated, INPARANOID (for two-species comparisons) and OrthoMCL (for multi-species comparisons) demonstrated the best overall balance, with both sensitivity and specificity exceeding 80% [28].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Orthology Inference Tools

| Tool | Method Type | Key Features | Reported Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| OrthoFinder [30] [31] | Phylogenetic | Infers rooted gene trees, species trees, and gene duplication events; uses DIAMOND and MCL | Highest ortholog inference accuracy on QfO benchmarks; comprehensive output |

| SonicParanoid2 [34] | Graph-based with Machine Learning | Uses AdaBoost to predict faster alignments; Doc2Vec for domain-based inference | Fast execution; accurate on QfO benchmarks; handles complex domain architectures |

| Broccoli [32] | Graph-based | Uses k-mer preclustering to simplify proteomes; machine learning for clustering | Reduced computational time for large datasets |

| OrthoMCL [28] | Graph-based | Normalizes BLAST scores for systematic bias; uses MCL for clustering | Good balance of sensitivity and specificity (>80%) for multiple species |

Impact of Alignment Tools on OrthoFinder Performance

OrthoFinder's flexibility in supporting different sequence search tools significantly impacts its performance. The default use of DIAMOND (Double Index Alignment of Next-Generation Sequencing Data) provides a substantial speed advantage over traditional BLAST, as DIAMOND is optimized for high-throughput processing while maintaining sensitivity [31]. Research has shown that the choice between DIAMOND and BLAST within the OrthoFinder pipeline does not result in large differences in the final orthogroups inferred [32]. This makes the combination of OrthoFinder with DIAMOND an optimal balance between speed and accuracy for large-scale plant genomic studies, which often involve dozens of genomes and hundreds of thousands of protein sequences.

OrthoFinder Protocol for Plant Gene Orthogroup Identification

Experimental Workflow and Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the complete analytical workflow for orthogroup identification in plant genomic research:

Diagram 1: Workflow for Orthogroup Identification

Step-by-Step Protocol

Input Data Preparation

- Protein Sequence Collection: For each plant species in your analysis, obtain proteome sequences in FASTA format. Ensure consistent gene nomenclature within each species file.

- Data Quality Control: Remove redundant sequences and sequences shorter than 30 amino acids. The OrthoFinder results directory will contain a file (

Orthogroups/Orthogroups_UnassignedGenes.tsv) listing genes not assigned to any orthogroup, which can help identify potentially problematic sequences [30].

Installing OrthoFinder and Dependencies

The conda installation method is strongly recommended as it automatically handles all dependencies, including DIAMOND and MCL [30]. For systems without conda, the larger bundled package (OrthoFinder.tar.gz) contains all necessary components.

Running OrthoFinder

Table 2: Key OrthoFinder Command-Line Parameters

| Parameter | Default | Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

-f <dir> |

Required | Input directory containing FASTA files | Essential for all analyses |

-t <int> |

16 | Number of parallel sequence search threads | Increase for large plant genomes (e.g., 40) |

-a <int> |

1 | Number of parallel analysis threads | Increase for multi-core systems (e.g., 8) |

-S <txt> |

diamond | Sequence search program | Use diamond_ultra_sens for improved sensitivity |

-M <txt> |

dendroblast | Gene tree inference method | Use msa for maximum accuracy |

-I <float> |

1.5 | MCL inflation parameter | Increase (e.g., 2.0) for stricter clustering |

-y |

Off | Split paralogous clades into separate HOGs | Recommended for plant genomes with duplications |

-s <file> |

None | User-specified rooted species tree | Use when known species tree is available |

Output Interpretation and Analysis

Primary Output Files: OrthoFinder produces several key output files in a dated results directory:

Phylogenetic_Hierarchical_Orthogroups/N0.tsv: The main orthogroup file replacing the deprecatedOrthogroups/Orthogroups.tsv[30]. According to Orthobench benchmarks, these phylogenetically-informed orthogroups are 12-20% more accurate than graph-based orthogroups [30].Species_Tree/SpeciesTree_rooted.txt: The inferred rooted species tree.Gene_Trees: Directory containing rooted gene trees for each orthogroup.Gene_Duplication_Events: Directory detailing gene duplication events mapped to both gene trees and species tree.

Downstream Analysis: For plant evolutionary studies, the hierarchical orthogroups (HOGs) at different taxonomic levels (N1.tsv, N2.tsv, etc.) are particularly valuable for studying lineage-specific gene family expansions [30]. These files contain orthogroups defined at each node of the species tree, enabling focused analysis on specific clades of interest.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Orthogroup Analysis

| Item | Function/Application | Implementation in Plant Genomics |

|---|---|---|

| OrthoFinder Software [30] [31] | Primary analysis platform for orthogroup and ortholog inference | Infers orthogroups, gene trees, species trees, and duplication events |

| DIAMOND Sequence Aligner [31] | High-speed sequence similarity search tool | Accelerates all-vs-all protein comparisons in large plant genomes |

| MCL Algorithm [30] | Graph clustering method for orthogroup identification | Groups homologous sequences into orthogroups based on similarity graphs |

| Plant Proteome FASTA Files | Input data for orthology inference | Curated protein sequences for each species analyzed |

| Reference Genomes [29] | Chromosome-level assemblies for mapping | Enables gene synteny analysis and validation of orthogroups |

| Multiple Sequence Alignment Tools (e.g., MAFFT) | Alignment of orthogroup sequences | Prepares data for phylogenetic tree inference |

| Tree Inference Tools (e.g., FastTree, RAxML) | Phylogenetic tree construction | Infers gene trees and species trees from aligned sequences |

| Computational Resources (HPC cluster) | Hardware for computationally intensive analyses | Enables analysis of dozens of plant genomes with thousands of genes |

Application in Plant Evolutionary Genomics: Case Studies

Evolutionary Analysis of Seasonal Gene Expression

OrthoFinder was instrumental in a study investigating the evolution of gene expression in four evergreen Fagaceae species (Quercus glauca, Q. acuta, Lithocarpus edulis, and L. glaber) under seasonal environments [29]. Researchers first assembled high-quality reference genomes for two species, then used OrthoFinder2 to identify 11,749 single-copy orthologous genes across all four species [29]. This orthogroup set enabled direct comparison of seasonal transcriptomic dynamics, revealing highly conserved gene expression in winter but divergent expression patterns during the growing season that correlated with species-specific timing of leaf flushing and flowering [29].

Identification of Conserved Cold-Response Transcription Factors

In a study identifying conserved cold-responsive transcription factors across eudicots, researchers employed orthogroup analysis to identify 10,549 orthogroups across five representative eudicot species [33]. This systematic approach enabled the discovery of 35 high-confidence conserved cold-responsive transcription factor orthogroups (CoCoFos), including both well-known regulators like CBFs and novel candidates such as BBX29, which was experimentally validated as a negative regulator of cold tolerance in Arabidopsis [33].

Gene Family Expansion in Desiccation-Tolerant Plants

OrthoFinder was used to analyze orthologous groups across 19 land plant species to identify gene families expanded in desiccation-tolerant lineages [20]. The analysis generated 26,406 orthogroups, which were filtered to 4,625 groups with at least one ortholog in all species [20]. Statistical enrichment tests identified orthogroups significantly expanded in desiccation-tolerant plants, providing insights into the genetic basis of this important adaptive trait [20].

Advanced Applications and Integration with Other Analytical Frameworks

The OrthoFinder pipeline serves as a critical foundation for more specialized evolutionary analyses in plant genomics. The orthogroups identified can be directly utilized for phylogenomic analyses, selection pressure assessment (dN/dS calculations), and gene family evolution studies. A key advancement in OrthoFinder is its ability to infer hierarchical orthogroups using rooted gene trees, which provides substantially more accurate orthogroup assignments compared to similarity graph-based methods alone [30]. For researchers studying plant genes with complex evolutionary histories, including those affected by whole-genome duplication events common in plant lineages, the -y parameter can be used to split paralogous clades below the root of a hierarchical orthogroup into separate groups, providing finer resolution of gene relationships [30]. Additionally, when analyzing new plant genomes in the context of existing orthogroup analyses, OrthoFinder's --assign function enables efficient addition of new species to previous orthogroups without recomputing the entire analysis [30], significantly reducing computational time for incremental dataset expansions.

The integration of high-quality genome assemblies with comprehensive transcriptomic data provides a powerful foundation for evolutionary studies. In plant gene research, orthogroup analysis offers a robust framework for identifying groups of genes descended from a single ancestral gene in a last common ancestor, enabling the tracing of gene evolution across species [35]. These analyses depend critically on the quality of the underlying genomic resources and the accurate measurement of gene expression through RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq). This article presents application notes and detailed protocols for generating and utilizing these fundamental datasets, framing them within the context of plant evolutionary genomics and the identification of conserved gene regulatory networks, such as those involved in cold stress response [33].

Application Notes: Core Concepts and Workflows

The Role of High-Quality Genome Assemblies in Evolutionary Studies

Genome assembly is the process of reconstructing the original DNA sequence from numerous short sequencing reads. For evolutionary studies, the quality of this assembly is paramount. Long-read sequencing technologies have revolutionized this field by producing extended DNA sequences capable of spanning intricate and repetitive genomic regions, which are common in plant genomes [36]. However, assembly errors are inevitable due to inherent genomic complexity and technological limitations. Tools like Inspector provide a comprehensive solution for genome assembly evaluation, offering both reference-free and reference-guided assessment, detection of small- and large-scale structural errors, and even the option for assembly error correction [36]. This is particularly valuable for plant species lacking a high-quality reference genome.

Recent advances, such as the "dual curation" process developed by the Vertebrate Genome Lab (VGL) and the Galaxy team, demonstrate the significant improvements possible through manual curation. This process involves curating both haplotypes of a genome simultaneously using a single Hi-C map, which streamlines the curation process and results in near error-free reference genomes essential for accurate downstream comparative analyses [37].

RNA-Seq Data Collection and Analysis for Transcriptomics

RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) is a high-throughput technology that enables comprehensive, genome-wide quantification of RNA abundance [38]. It has become a routine component of molecular biology research, providing insights into gene expression under different conditions, such as stress responses, and across different species. A typical RNA-Seq workflow involves multiple critical steps, from sample preparation and sequencing to computational analysis [38]. The reliability of differential gene expression (DGE) analysis, a common goal of RNA-Seq studies, depends strongly on thoughtful experimental design, particularly with respect to biological replicates and sequencing depth [38]. While three replicates per condition is often considered the minimum standard, higher replication increases statistical power, especially when biological variability is high. Sufficient sequencing depth (e.g., ~20–30 million reads per sample for standard DGE analysis) is also crucial for detecting lowly expressed transcripts [38].

Integrating Genomic and Transcriptomic Data for Orthogroup Analysis

Orthogroup analysis provides the evolutionary context needed to interpret genomic and transcriptomic data across multiple species. An orthogroup is defined as the set of genes that are descended from a single gene in the last common ancestor of all the species being considered [35]. Identifying these groups accurately is fundamental to comparative genomics. OrthoFinder is a widely used algorithm that solves a previously undetected gene length bias in orthogroup inference, resulting in significant improvements in accuracy [35]. This is particularly important given the variation in gene lengths within and between plant genomes.

The power of this integrated approach was demonstrated in a phylotranscriptomic analysis of cold-treated seedlings from eudicots, which identified 35 high-confidence conserved cold-responsive transcription factor orthogroups (CoCoFos) [33]. This study, which combined orthogroup analysis with RNA-Seq data from diverse species, successfully identified known and novel regulators of cold tolerance, illustrating how leveraging these methodologies can uncover key evolutionary patterns and functional gene networks in plants.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: A Robust Pipeline for RNA-Seq Data Analysis

This protocol outlines a complete workflow for processing RNA-Seq data from raw sequences to the identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs), incorporating best practices for quality control and normalization [38] [39].

- Step 1: Quality Control (QC) of Raw Reads

- Step 2: Read Trimming

- Use Trimmomatic or Cutadapt to clean the data by removing low-quality bases and adapter sequences. Avoid over-trimming, as this can reduce data depth and weaken subsequent analysis [38].

- Step 3: Read Alignment or Pseudoalignment

- Option A (Alignment): Use a splice-aware aligner like STAR or HISAT2 to map the cleaned reads to a reference genome [38]. This is suitable when a high-quality genome is available.

- Option B (Pseudoalignment): Use Salmon or Kallisto to estimate transcript abundances without full base-by-base alignment. These methods are faster and use less memory, making them well-suited for large datasets [39].

- Step 4: Post-Alignment QC and Quantification

- If alignment was performed, use tools like SAMtools or Qualimap to remove poorly aligned or multi-mapped reads, which can artificially inflate counts [38].

- Generate a count matrix using tools like featureCounts or HTSeq-count. This matrix summarizes the number of reads mapped to each gene in each sample [38].

- Step 5: Normalization and Differential Expression Analysis

- Normalize the raw count data to account for differences in sequencing depth and library composition. Common methods include TMM (used in edgeR) or the median-of-ratios method (used in DESeq2) [38].

- Perform Differential Expression (DE) analysis using a robust statistical method. Common choices include DESeq2, edgeR, or voom-limma [38] [39]. For complex designs or small sample sizes, consider methods like dearseq [39].

The following workflow diagram summarizes this RNA-seq analysis pipeline:

Protocol 2: Genome Assembly Evaluation Using Inspector

This protocol details the use of Inspector for assessing the quality of long-read genome assemblies, a critical step before using the assembly in orthogroup analysis [36].

- Step 1: Installation and Data Preparation

- Install Inspector from its GitHub repository (

https://github.com/ChongLab/Inspector_protocol). - Gather your long-read sequencing data and the assembled genome (contigs or scaffolds) in FASTA format.

- Install Inspector from its GitHub repository (

- Step 2: Running Inspector in Reference-Guided Mode

- If a reference genome is available for a closely related species, run Inspector in reference-guided mode. This provides the most comprehensive assessment by comparing your assembly to the reference.

- Use the command:

inspector.py -c [YOUR_CONTIGS.fa] -r [REFERENCE.fa] -o [OUTPUT_DIR]

- Step 3: Running Inspector in Reference-Free Mode

- If no reference is available, use Inspector's reference-free mode. This leverages the original long reads to evaluate assembly consensus quality and identify potential misassemblies.

- Use the command:

inspector.py -c [YOUR_CONTIGS.fa] -l [LONG_READS.fq] -o [OUTPUT_DIR]

- Step 4: Interpreting the Output

- Examine the basic contig statistics (e.g., N50, total length) provided in the report.

- Critically review the list of structural errors (misassemblies, local indels) which provides their precise genomic locations and types. This is vital for planning subsequent manual curation.

- Step 5: Optional Assembly Correction

- Based on the evaluation, you can use Inspector's error correction function to automatically correct identified small-scale structural errors, which can improve the overall quality value of the assembly.

Protocol 3: Conducting Orthogroup Analysis with OrthoFinder

This protocol describes how to infer orthogroups from the protein sequences of multiple plant species using OrthoFinder, facilitating evolutionary comparisons [35].

- Step 1: Input Data Preparation

- Collect protein sequence files in FASTA format (

.faor.fasta) for each species to be analyzed. These can be derived from annotated genome assemblies or transcriptomes. - Ensure the files are clearly named (e.g.,

Oryza_sativa.fa,Arabidopsis_thaliana.fa).

- Collect protein sequence files in FASTA format (

- Step 2: Running OrthoFinder

- The basic command is:

orthofinder -f [DIRECTORY_CONTAINING_FASTA_FILES] - OrthoFinder will automatically run BLAST, perform its gene length normalization, and cluster the sequences.

- The basic command is:

- Step 3: Analysis of Results

- The primary output file for orthogroups is

Orthogroups.txt. This file lists all orthogroups and the genes from each species that belong to them. - The

Orthogroups_UnassignedGenes.txtfile contains genes not assigned to any orthogroup.

- The primary output file for orthogroups is

- Step 4: Integration with Transcriptomic Data

- To conduct a phylotranscriptomic study like the one identifying cold-responsive orthogroups [33], overlay RNA-Seq expression data (e.g., DEG lists from Protocol 1) onto the orthogroups.

- Identify orthogroups that are enriched for differentially expressed genes across multiple species, as these represent conserved transcriptional responses.

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of an integrated analysis that combines genome assembly and RNA-seq data for orthogroup inference and phylotranscriptomic discovery:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents, tools, and software essential for executing the genomics and transcriptomics workflows described in this article.

Table 1: Essential Research Tools and Resources for Genomic and Transcriptomic Analysis

| Item Name | Type/Category | Primary Function in Research | Example Application in Protocols |

|---|---|---|---|

| Galaxy Filament [37] | Data Access Framework | Unifies access to reference genomic data, allowing users to explore assemblies and annotations and combine public datasets with their own data. | Sourcing genomic data for multiple species prior to orthogroup analysis. |

| GalaxyMCP [37] | AI Agent Interface | Connects Galaxy's tools and APIs to AI agents via natural language, enabling conversational, reproducible analysis. | Assisting researchers in planning and executing complex RNA-Seq or assembly workflows. |

| Inspector [36] | Genome Evaluation Tool | Provides comprehensive evaluation of long-read genome assemblies, detecting structural errors and enabling correction. | Protocol 2: Assessing the quality of a newly assembled plant genome before annotation. |

| OrthoFinder [35] | Bioinformatics Algorithm | Infers orthogroups from protein sequences across multiple species with high accuracy, correcting for gene length bias. | Protocol 3: Identifying groups of orthologous genes from annotated plant genomes. |

| DESeq2 / edgeR [38] [39] | Statistical Software Package | Identifies differentially expressed genes from RNA-Seq count data, incorporating robust normalization and statistical testing. | Protocol 1: Determining which genes are up- or down-regulated in response to an experimental treatment. |

| STAR / HISAT2 [38] | Read Alignment Software | Maps RNA-Seq reads to a reference genome, accurately handling splice junctions. | Protocol 1: Aligning cleaned reads to a reference genome for transcript quantification. |

| Salmon [39] | Transcript Quantification Tool | Estimates transcript abundances from RNA-Seq data using ultra-fast pseudoalignment, bypassing full alignment. | Protocol 1: Rapid quantification of gene expression levels for downstream differential analysis. |

| Trimmomatic [38] [39] | Data Preprocessing Tool | Removes adapter sequences and trims low-quality bases from raw RNA-Seq reads. | Protocol 1: The initial cleaning step of the RNA-Seq analysis pipeline. |

Data Presentation and Comparison

RNA-Seq Normalization Methods

A critical step in RNA-Seq analysis is normalization, which adjusts raw read counts to make them comparable across samples. The choice of method depends on the goals of the analysis.

Table 2: Comparison of Common RNA-Seq Normalization Methods [38]

| Method | Sequencing Depth Correction | Gene Length Correction | Library Composition Correction | Suitable for DE Analysis? | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPM (Counts per Million) | Yes | No | No | No | Simple scaling by total reads; heavily affected by highly expressed genes. |

| RPKM/FPKM (Reads/Fragments per Kilobase per Million) | Yes | Yes | No | No | Adjusts for gene length; useful for within-sample comparisons but still affected by composition bias for between-sample comparisons. |

| TPM (Transcripts per Million) | Yes | Yes | Partial | No | A improvement over RPKM/FPKM that scales to a constant total; good for cross-sample comparison but not for formal DE testing. |

| median-of-ratios (DESeq2) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Robust to composition biases; the default and recommended method for DESeq2. |

| TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values, edgeR) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Robust to composition biases; the default and recommended method for edgeR. |

The synergistic use of genomics and transcriptomics, powered by robust protocols for genome assembly, RNA-Seq analysis, and orthogroup inference, provides an unparalleled toolkit for evolutionary plant genomics. As technologies advance—with frameworks like Galaxy Filament simplifying data access [37] and AI agents like GalaxyMCP democratizing complex analyses [37]—the potential for discovery grows. By adhering to detailed protocols for quality control, normalization, and evolutionary classification, researchers can reliably uncover conserved genetic programs, such as the cold-responsive CoCoFos [33], that underlie adaptation and diversity in the plant kingdom. This integrated approach is fundamental to advancing our understanding of plant evolution and for identifying genetic resources for crop improvement.

Application Note

Orthogroup analysis has emerged as a foundational framework for the evolutionary study of plant genes, enabling researchers to cluster homologous genes across multiple species into putative gene families. This approach powerfully illuminates gene duplication events, functional divergence, and the deep evolutionary history of plant genomes. However, orthogroup classification based on sequence homology alone provides an incomplete picture. The integration of evolutionary data from phylogenetics and synteny with functional data from co-expression networks creates a powerful synergistic effect, offering profound insights into gene function, regulatory evolution, and the genetic basis of adaptive traits. This integration is particularly crucial for translating genomic information into actionable biological knowledge for crop improvement and drug development from plant sources.

Recent advances in network-based analytical approaches have demonstrated particular value for overcoming limitations of traditional phylogenetic methods, especially for complex gene families with intricate duplication histories [40]. These integrated frameworks have been successfully applied to diverse plant gene families, including the well-characterized AGAMOUS family of floral development genes [40], auxin response factors (ARFs) [41], and zinc finger-BED transcription factors [42]. The protocols detailed in this document provide a comprehensive roadmap for implementing these powerful integrative approaches.