Overcoming the Hurdles: A Comprehensive Guide to Single-Cell RNA Sequencing in Plant Research

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) represents a paradigm shift in plant biology, enabling the dissection of cellular heterogeneity with unprecedented resolution.

Overcoming the Hurdles: A Comprehensive Guide to Single-Cell RNA Sequencing in Plant Research

Abstract

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) represents a paradigm shift in plant biology, enabling the dissection of cellular heterogeneity with unprecedented resolution. However, its application in plants is fraught with unique challenges, from cell wall digestion to significant transcriptional stress responses. This article provides a foundational exploration of scRNA-seq principles, details methodological advances and key applications in model plants and crops, offers troubleshooting strategies for technical optimization, and discusses validation through multi-omics integration. Aimed at researchers and scientists, this guide synthesizes current knowledge to empower robust experimental design and data interpretation, paving the way for new discoveries in plant development, stress response, and host-microbe interactions.

The Plant Single-Cell Landscape: Principles, Potential, and Inherent Hurdles

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the main advantages of single-cell RNA sequencing over bulk RNA sequencing in plant studies? Bulk RNA-seq provides an average gene expression profile from a mixed cell population, which often masks the heterogeneity between different cell types. In contrast, scRNA-seq allows for the resolution of gene expression at the individual cell level. This enables the identification of rare cell types, the construction of developmental trajectories, and the discovery of cell-type-specific responses to environmental stimuli, such as how different root cell types respond uniquely to drought or salt stress [1] [2] [3].

My protoplasting process is inefficient or leads to low RNA quality. What are my options? Inefficient protoplasting, often caused by the rigid and varying composition of plant cell walls, is a major bottleneck. A robust alternative is single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq). This method involves isolating nuclei instead of whole cells, bypassing the need for cell wall digestion. snRNA-seq is compatible with frozen or difficult-to-dissociate tissues and has been shown to have gene detection sensitivity similar to protoplast-based methods [1] [4].

After sequencing, my single-cell data has lost all spatial information. How can I recover it? The loss of spatial location is a known limitation of standard scRNA-seq. Spatial transcriptomics techniques are designed to preserve this information. These methods capture gene expression data directly from tissue sections while retaining the positional context. For a more targeted approach, you can also use in situ hybridization or reporter lines to map the expression of key genes identified in your scRNA-seq data back to the original tissue [1] [4].

How can I estimate cell type proportions from my existing bulk RNA-seq data? The process of estimating cell type proportions from bulk data is called deconvolution. Computational tools like MuSiC, SCDC, and Scaden can perform this task. These methods use a reference scRNA-seq or snRNA-seq dataset from the same or a closely related species to infer the cellular composition of your bulk RNA-seq samples. This is a cost-effective strategy to gain insights into cellular heterogeneity without performing new single-cell experiments [5] [6].

What are some common data analysis pipelines for plant scRNA-seq data? Several computational tools and pipelines are available. The analysis workflow typically involves quality control, filtering, normalization, dimensionality reduction, clustering, and marker gene identification. Popular suites include Scanpy and Seurat. For instance, one can replicate the analysis of Arabidopsis root scRNA-seq data using the Scanpy toolkit within the Galaxy platform [7].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Table 1: Troubleshooting Guide for Plant Single-Cell RNA Sequencing.

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Cell Viability/Robot Yieldufter Protoplasting | Over-digestion with cell wall enzymes; harsh physical dissociation; extended processing time. | Optimize enzyme cocktail concentration and incubation time [1] [4]; Use snRNA-seq on nuclei from frozen tissue to avoid protoplasting entirely [1] [4] [6]. |

| High Ambient RNA/Background Noise | Cell rupture during protoplasting or nuclei isolation releasing RNA into the solution. | Include a viability dye during cell sorting; use bioinformatic tools (e.g., SoupX, DecontX) to subtract background RNA post-sequencing [8]. |

| Low Gene Detection per Cell | Low mRNA capture efficiency; poor RNA quality; issues with reverse transcription or amplification. | Ensure tissue is fresh and handled quickly; use protocols with Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) to improve quantification [8]; validate library quality pre-sequencing. |

| Inability to Distinguish Cell Types | Insufficient sequencing depth; over-digestion causing transcriptional stress; high technical noise. | Increase read depth per cell; ensure rapid processing to preserve native transcriptome; use high-resolution clustering algorithms and validate with known marker genes [3] [7]. |

| Batch Effects Between Samples | Technical variations from processing samples on different days or with different reagent batches. | Process samples in parallel where possible; use combinatorial indexing methods (e.g., sciRNA-seq); apply batch effect correction tools (e.g., Harmony, BBKNN) during data analysis [8]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: Protoplast-based scRNA-seq for Root Tips

Principle: This method involves digesting the cell wall to release protoplasts, which are then captured and processed using droplet-based systems like the 10x Genomics Chromium platform.

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Tissue Harvesting: Excise 1-2 mm root tips from seedlings (e.g., Arabidopsis, rice) and immediately place in pre-chilled enzyme solution.

- Cell Wall Digestion: Incubate tissue in a protoplasting solution (e.g., containing cellulase, pectolyase, and macerozyme) for 30-90 minutes with gentle agitation.

- Protoplast Purification: Filter the digest through a 30-40 μm cell strainer to remove debris. Pellet protoplasts by gentle centrifugation and resuspend in a protective buffer.

- Viability and Counting: Check protoplast viability (>80% is ideal) using trypan blue or fluorescein diacetate staining and count with a hemocytometer.

- Single-Cell Library Preparation: Load the protoplast suspension onto a microfluidic device per the manufacturer's instructions (e.g., 10x Genomics). The system will encapsulate single cells into droplets with barcoded beads for reverse transcription.

- cDNA Amplification and Sequencing: Break the droplets, purify the barcoded cDNA, and perform PCR amplification. Construct sequencing libraries and sequence on an Illumina platform [1] [3] [4].

Protocol B: Single-Nucleus RNA-seq (snRNA-seq) for Challenging Tissues

Principle: This method isolates nuclei from tissues that are recalcitrant to protoplasting (e.g., woody tissues, mature leaves, frozen samples), enabling the profiling of cellular heterogeneity without the need for cell wall digestion.

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Homogenization: Flash-freeze tissue in liquid N₂. Grind the frozen tissue to a fine powder and homogenize it in a lysis buffer containing non-ionic detergent to release nuclei while keeping them intact.

- Nuclei Purification: Filter the homogenate through a mesh (e.g., 30-40 μm) to remove cellular debris. Purify nuclei via density gradient centrifugation (e.g., using Percoll or sucrose gradients).

- Staining and Sorting: Resuspend the nuclei pellet and stain with DAPI. Optionally, sort nuclei using Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) to select for intact, single nuclei.

- Single-Nucleus Library Preparation: Process the nuclei suspension through a single-cell platform (e.g., 10x Genomics). Subsequent steps for barcoding, cDNA synthesis, and library preparation are similar to protoplast-based methods [4] [6].

Decision Workflow for scRNA-seq Methods

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Kits for Plant Single-Cell Experiments.

| Reagent/Kits | Function | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Wall Digesting Enzymes | Breaks down cellulose and pectin to release protoplasts. | A mixture of cellulase (e.g., Onozuka R-10) and pectolyase (e.g., Y-23) is standard for digesting Arabidopsis root tips [1] [4]. |

| 10x Genomics Chromium Controller & Kits | A high-throughput, droplet-based system for capturing single cells/nuclei and barcoding RNA. | The widely used platform for generating single-cell libraries from thousands of plant protoplasts or nuclei in parallel [3] [8] [7]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random barcodes that label individual mRNA molecules to correct for PCR amplification bias. | Incorporated in bead-based methods (Drop-seq, inDrop, 10x Genomics) for accurate digital gene expression counting [8]. |

| DAPI (4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) | A fluorescent stain that binds to DNA, used to identify and count nuclei. | Essential for quality control and FACS sorting during snRNA-seq protocols to select for intact nuclei [6]. |

| Scanpy / Seurat | Open-source computational toolkits for analyzing scRNA-seq data. | Used for the entire analysis pipeline, from quality control and filtering to clustering and trajectory inference on plant single-cell data [7]. |

Data Analysis and Computational Tools

scRNA-seq Data Analysis Workflow

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for scRNA-seq Analysis.

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Application in Plant Research |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Ranger | Processes raw sequencing data from 10x Genomics, performing barcode/qc, alignment, and feature counting. | The standard first step for analyzing data from 10x experiments, e.g., used in studies profiling Arabidopsis and maize roots [6] [7]. |

| Scanpy | A comprehensive Python-based toolkit for analyzing single-cell gene expression data. | Used to replicate the analysis of Arabidopsis root scRNA-seq data, including clustering to identify major cell types [7]. |

| Seurat | An R package designed for QC, analysis, and exploration of single-cell data. | Commonly used in plant single-cell publications (e.g., Denyer et al. 2019) for its robust clustering and visualization capabilities [7]. |

| Scaden | A deep-learning-based tool for deconvoluting bulk RNA-seq data to estimate cell-type composition. | Can be trained on plant scRNA/snRNA-seq data to predict cell type proportions in bulk samples from the same species [5] [6]. |

| Monocle, PAGA | Algorithms for inferring developmental trajectories and ordering cells along a pseudotime line. | Applied to root scRNA-seq data to reconstruct the continuous trajectory of cell differentiation from meristem to mature cells [3]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is the plant cell wall a primary obstacle in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq)?

The plant cell wall is a rigid, elaborate extracellular matrix that encloses each cell. Its primary role is to provide structural support and turgor pressure, but this same rigidity physically prevents the gentle dissociation of individual cells needed for scRNA-seq. Unlike animal cells, plant cells are cemented together by a pectin-rich middle lamella [9]. During tissue dissociation, the mechanical and enzymatic stress required to break down these walls often damages cells, triggers rapid transcriptional stress responses, and alters the very gene expression profiles researchers aim to study [10] [11].

Q2: What is protoplasting, and how does it help overcome this challenge?

Protoplasting is the process of enzymatically removing the cell wall to create naked plant cells, or protoplasts. This is a critical step for plant scRNA-seq because it liberates individual cells for capture and sequencing. Protoplasts are generated by incubating plant tissues, such as leaves, in a solution containing cell wall-degrading enzymes like cellulase and macerozyme [12] [13]. A successful protoplasting protocol yields a high number of intact, viable cells without their walls, making them amenable to standard single-cell workflows.

Q3: What are the major technical challenges associated with the protoplasting process?

The protoplasting process itself introduces significant technical challenges that can compromise scRNA-seq data:

- Induced Transcriptional Stress: The enzymatic digestion and osmotic stress during protoplast isolation can rapidly and dramatically alter gene expression. This means the transcriptome you capture may reflect the stress of the isolation process rather than the native physiological state of the cell [10].

- Cellular Heterogeneity and Bias: Not all cell types are equally susceptible to cell wall digestion. Some cell types, like those with thicker secondary walls (e.g., xylem fibers), may be under-represented in the final dataset. Furthermore, protoplasts from different cell types can vary in size and fragility, leading to selection bias during isolation and capture [11] [14].

- Loss of Spatial Information: Once cells are released from the tissue as protoplasts, all information about their original spatial context and cellular neighborhood within the plant organ is lost [11] [14].

Q4: How can I tell if my protoplasting procedure is causing excessive stress?

Signs of an overly stressful protoplasting procedure include:

- Low protoplast viability (e.g., below 80-85% as assessed by FDA staining) [13].

- Low RNA Quality after isolation, indicated by a low RNA Integrity Number (RIN).

- ScRNA-seq data that shows high expression of well-known stress-responsive genes, such as those for heat shock proteins (HSPs), wound-responsive genes, and hormones like jasmonic acid (JA) and ethylene [10] [15].

Q5: What are the emerging alternatives to protoplasting for plant scRNA-seq?

To circumvent the issues with protoplasting, researchers are developing protoplast-free methods. The most prominent of these is single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq). This approach involves isolating nuclei instead of whole cells. Since the nucleus lacks a cell wall, it can be extracted with gentler, mechanical homogenization, minimizing stress-induced artifacts. Paired with spatial transcriptomics, which maps gene expression back to its original tissue location, snRNA-seq provides a powerful strategy for capturing comprehensive and context-preserved plant transcriptomes [14].

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Common Protoplasting Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Protoplast Yield | Incorrect enzyme combination/concentration; Inadequate digestion time; Unsuitable plant material (age, tissue type). | - Optimize enzyme cocktails (e.g., 1.0-1.5% Cellulase R-10, 0.2-0.6% Macerozyme R-10) [12] [13].- Extend digestion time (e.g., 6-16 hours) but monitor viability [12].- Use young, healthy leaves from 3-4 week-old plants [12]. |

| Poor Protoplast Viability | Over-digestion with enzymes; Osmotic imbalance; Mechanical damage during isolation. | - Include osmotic stabilizers (e.g., 0.4-0.6 M mannitol/sorbitol) in all solutions [12] [13].- Handle protoplasts gently; use wide-bore pipettes.- Reduce digestion time and use viability stains (e.g., Fluorescein diacetate) to monitor [16] [13]. |

| High Stress Gene Expression in scRNA-seq Data | Protoplasting procedure is too harsh; Prolonged isolation time. | - Minimize the time from protoplast isolation to cell lysis [10].- Compare with a snRNA-seq dataset from the same tissue to identify protoplasting-specific stress genes [14].- Test shorter digestion times and gentler enzyme formulations. |

| Clogging in scRNA-seq Microfluidics | Incomplete removal of cell wall debris; Presence of large cellular aggregates. | - Filter protoplast suspension through a 30-40 μm nylon mesh before loading [12].- Allow debris to settle and carefully pipette the supernatant. |

Table 2: Optimizing Key Parameters for Protoplasting and scRNA-seq

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Technical Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Concentration | 1.0% - 1.5% Cellulase; 0.2% - 0.6% Macerozyme [12] [13] | High concentrations increase yield but reduce viability. Requires empirical optimization for each species/tissue. |

| Digestion Time | 6 - 16 hours [12] | Shorter times may be insufficient; longer times increase stress. |

| Osmotic Stabilizer | 0.4 M - 0.6 M Mannitol or Sorbitol [12] [13] | Critical for maintaining protoplast integrity. Concentration must be optimized. |

| Plasmodesmata Disruption | Minutes after tissue slicing [9] | Rapid transcriptional changes occur. Speed from dissection to fixation is critical. |

| Viability Threshold | > 85% [13] | A minimum viability is required for high-quality library prep. |

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Methodology: Protoplast Isolation from Leaf Mesophyll

This protocol is adapted from established methods in Brassica carinata and Toona ciliata [12] [13].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent | Function |

|---|---|

| Cellulase Onozuka R-10 | Degrades cellulose microfibrils in the primary cell wall [9] [12]. |

| Macerozyme R-10 | Degrades pectin in the middle lamella, separating cells [9] [12]. |

| Mannitol | Provides osmotic support to prevent protoplast bursting [12] [13]. |

| MES Buffer | Maintains stable pH during enzymatic digestion [12]. |

| Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂) | Helps stabilize the protoplast membrane [12]. |

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | Reduces adhesion and adsorption of protoplasts to surfaces [13]. |

Step-by-Step Workflow:

Title: Protoplast Isolation Workflow

- Plant Material Preparation: Use fully expanded, young leaves from 3-4 week-old plants grown under sterile conditions. Avoid old or stressed tissues [12].

- Tissue Slicing: Using a sharp razor blade, slice leaves into 0.5-1 mm thin strips. This dramatically increases the surface area for enzyme action. Note: Transcriptional stress responses begin within minutes of wounding [9].

- Plasmolysis: Submerge the tissue slices in a plasmolyzing solution (e.g., CPW salts with 0.4-0.6 M mannitol) for 30-60 minutes. This causes the protoplast to shrink away from the cell wall, reducing damage during subsequent slicing and initiating enzyme penetration [12].

- Enzymatic Digestion: Transfer the tissue to the enzyme solution (e.g., 1.5% Cellulase R-10, 0.6% Macerozyme R-10, 0.4 M mannitol, 10 mM MES, 1 mM CaCl₂, pH 5.7). Incubate in the dark at 22-25°C for 6-16 hours with very gentle shaking (40-50 rpm) [12] [13].

- Protoplast Release and Purification: a. Gently swirl the flask to release protoplasts. Filter the suspension through a 30-40 μm nylon mesh into a fresh tube to remove undigested debris [12]. b. Centrifuge the filtrate at 100 x g for 10 minutes to pellet the protoplasts. c. Carefully remove the supernatant and resuspend the pellet in a washing solution (e.g., W5 solution: 154 mM NaCl, 125 mM CaCl₂, 5 mM KCl, 5 mM glucose, pH 5.7). Repeat the centrifugation step [12].

- Viability and Yield Assessment: Resuspend the final pellet in a known volume of osmoticum. Determine yield using a hemocytometer. Assess viability by mixing a protoplast aliquot with an equal volume of 0.01% Fluorescein Diacetate (FDA); viable cells will fluoresce green under a fluorescence microscope [16] [13]. A viability of >85% is ideal for scRNA-seq.

Detailed Methodology: Identifying Stress Responses in scRNA-seq Data

Step-by-Step Workflow:

Title: Transcriptional Stress Analysis Workflow

- Data Preprocessing: After standard alignment and quantification, perform rigorous quality control. Filter out cells with high mitochondrial gene percentage (indicative of apoptosis/necrosis) and an unusually high number of detected genes, which can be a sign of doublets or stressed cells [10].

- Differential Expression Analysis: Identify genes that are significantly upregulated in your protoplast dataset compared to a bulk RNA-seq reference from intact tissue, or compare clusters within your data that may represent "stressed" vs. "unstressed" cell states.

- Pathway Enrichment Analysis: Input the list of upregulated genes into enrichment analysis tools (e.g., GO, KEGG). Look for over-represented pathways such as "response to wounding," "heat response," "JA/ET-activated signaling pathway," and "response to oxidative stress" [15] [17].

- Cross-Reference with Known Stress Markers: Actively search your dataset for the expression of canonical stress markers [15] [17]:

- Heat Shock Proteins (HSPs): e.g., HSP70, HSP90

- Wound-Responsive Genes: e.g., JAZ family genes, VSP2

- Hormone Signaling: Jasmonic Acid (LOX2, OPR3), Ethylene (ACS6, ERF1)

- Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS): RBOHD, APX, CAT

- Interpretation: Widespread, high expression of these genes across most cell types suggests a generalized, protocol-induced stress. If confined to specific clusters, it may reflect genuine biological stress in that cell type or differential sensitivity to the isolation procedure.

The field of transcriptomics has undergone a profound transformation, evolving from bulk RNA sequencing that averages gene expression across entire tissues to highly sophisticated methods capable of analyzing gene expression at the single-cell level. This revolution is particularly significant for plant research, where cellular heterogeneity plays a crucial role in development, stress responses, and physiological functions. Traditional bulk RNA sequencing obscures critical cell-to-cell variations by providing population-averaged data, making it difficult to reveal rare cell subpopulations and their subtle gene expression differences [18] [19]. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) overcomes this limitation by capturing expression profiles at the single-cell level, enabling researchers to characterize cellular diversity with exceptional resolution [19].

However, a significant technological gap existed between low-throughput single-cell methods and the need for large-scale analysis. Early single-cell transcriptomic approaches relied on techniques such as laser capture microdissection (LCM) and manual cell picking, which were labor-intensive and limited in throughput [18]. These methods allowed for the isolation of cells from precisely defined spatial regions within tissue sections but could only process a limited number of cells per experiment [18]. The advent of high-throughput droplet microfluidics marked a pivotal milestone, enabling researchers to profile thousands to millions of individual cells simultaneously while dramatically reducing costs per cell [20] [21] [22]. This technical article explores these key technological milestones, with a specific focus on addressing plant-specific research challenges through troubleshooting guides and frequently asked questions.

Technological Evolution: From Low-Throughput to High-Throughput Platforms

Pre-Droplet Era: Low-Throughput and Early Spatial Methods

Before droplet microfluidics became established, researchers relied on several foundational technologies for single-cell analysis:

Laser Capture Microdissection (LCM): This technology laid the foundation for direct cutting of target cells under a microscope using lasers [18]. Researchers prepared tissues into numerous frozen sections and sequenced them separately to obtain regionalized transcriptome data. Subsequent methods like Tomo-seq improved quantitative accuracy and spatial resolution by refining the cDNA library construction process [18].

In Situ Hybridization Technologies: Early smFISH (single-molecule fluorescence in situ hybridization) was limited by probe number and could detect only a few genes [18]. This evolved through seqFISH, which used repeated hybridization-imaging-stripping cycles with binary encoding to broaden transcript detection, and MERFISH, which added error-robust codes and combinatorial labeling to improve accuracy and speed [18].

In Situ Sequencing: Methods like padlock probes and rolling circle amplification enabled direct sequencing of transcripts within tissue sections, laying the groundwork for the field [18].

These early methods provided valuable spatial information but were constrained by limited throughput, low multiplexing capability, and technical challenges in implementation.

The High-Throughput Droplet Revolution

Droplet-based single-cell RNA sequencing has redefined biological research by resolving cellular heterogeneity with an unprecedented precision [22]. The core innovation came from integrating barcoded gel beads within a water-in-oil emulsion system, where each bead carries millions of oligonucleotides designed for specific mRNA capture and molecular labeling [22].

Key Milestone Technologies:

inDrop: One of the first high-throughput methods establishing the microfluidic droplet barcoding platform [20].

Drop-seq: Utilized a simpler, more affordable approach with barcoded beads [22].

10× Genomics Chromium System: Currently the gold standard, achieving superior cell capture efficiency (65-75% vs. 30-60% for alternatives) and gene detection sensitivity (1000-5000 genes/cell) [22].

scifi-RNA-seq: A breakthrough approach that combines one-step combinatorial preindexing of entire transcriptomes inside permeabilized cells with subsequent single-cell RNA-seq using microfluidics [21]. This method massively increases the throughput of droplet-based single-cell RNA-seq, providing a straightforward way to multiplex thousands of samples in a single experiment [21].

smRandom-seq: Specifically designed for bacterial single-cell RNA sequencing, using random primers for in situ cDNA generation, droplets for single-microbe barcoding, and CRISPR-based rRNA depletion for mRNA enrichment [20].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Major High-Throughput scRNA-seq Platforms

| Platform | Throughput (Cells per Run) | Cell Capture Efficiency | Gene Detection Sensitivity | Multiplet Rate | Key Innovations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10× Genomics Chromium | 10,000-100,000 | 65-75% | 1000-5000 genes/cell | <5% | GEM technology, optimized microfluidics [22] |

| BD Rhapsody | Comparable to 10× | Similar cell capture | Similar gene sensitivity | N/A | Magnetic bead cell capture [23] |

| Drop-seq | Thousands | 30-60% | Lower than 10× | 5-15% | Simpler, more affordable barcoding [22] |

| scifi-RNA-seq | Up to 1,000,000 | N/A | High transcriptome complexity | Reduced via combinatorial indexing | Combinatorial preindexing, massive overloading [21] |

| smRandom-seq | ~10,000 bacteria | High species specificity | ~1000 genes/bacterium | 1.6% doublet rate | Random primers, CRISPR rRNA depletion [20] |

Special Considerations for Plant Single-Cell Transcriptomics

Plant researchers face unique challenges when applying single-cell RNA sequencing technologies:

- Rigid Cell Walls: Impede clean cryosectioning and present barriers to protoplast isolation [18].

- Expansive Vacuoles: Dilute intracellular RNA content, reducing transcript capture efficiency [18].

- Abundant Polyphenols: Inhibit enzymatic reactions essential for library preparation [18].

- Limited Reference Genomes: Hinder precise read mapping for many plant species [18].

- Lack of Poly(A) Tails on Bacterial mRNA: Makes standard poly(T) capture methods incompatible for plant-associated microbes [20].

Table 2: Plant-Specific Challenges and Potential Solutions

| Challenge | Impact on scRNA-seq | Potential Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Rigid Cell Walls | Difficult protoplast isolation, sectioning | Optimized enzymatic digestion protocols, spatial transcriptomics [18] |

| Expansive Vacuoles | Diluted intracellular RNA content | Nuclear sequencing, amplification strategies [18] |

| Abundant Polyphenols | Inhibition of enzymatic reactions | Polyphenol adsorbents, specialized extraction buffers [18] |

| Limited Reference Genomes | Impedes precise read mapping | De novo transcriptome assembly, cross-species mapping [18] |

| Diverse Plant-Associated Microbes | Incompatibility with standard poly(T) capture | smRandom-seq with random primers [20] |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the maximum throughput achievable with current droplet-based scRNA-seq platforms? The scifi-RNA-seq method can resolve up to 1 million single-cell transcriptomes with 384-well preindexing, vastly exceeding the barcoding capacity of three-round combinatorial indexing [21]. Standard 10× Genomics Chromium systems typically process 10,000-100,000 cells per run, while optimized methods can significantly exceed these numbers [22].

Q2: How can we address the challenge of low mRNA capture efficiency in droplet systems? Typical mRNA capture efficiency ranges from 10-50% of cellular transcripts [22]. Recent protocol enhancements have improved this through template-switch oligo (TSO) strategies, which enable cDNA synthesis independent of poly(A) tails by binding to the 3' end of newly synthesized cDNA during reverse transcription [22]. Additionally, CRISPR-based rRNA depletion can dramatically reduce rRNA percentage (83% to 32%) in bacterial samples, effectively enriching mRNA reads [20].

Q3: What strategies exist for reducing doublets/multiplets in droplet experiments? Conventional systems maintain multiplet rates below 5% when following optimal loading concentrations [22]. The scifi-RNA-seq approach uses combinatorial barcoding to resolve individual transcriptomes from overloaded droplets, effectively retaining and demultiplexing profiles that would otherwise be discarded as doublets [21]. Advanced droplet sorters like NOVAsort can discern droplets based on both size and fluorescence intensity, achieving a 1000-fold reduction in false positives [24].

Q4: How can we adapt droplet technologies for plant-specific challenges? Current plant-focused efforts pursue two parallel objectives: optimizing existing spatial transcriptomic platforms for botanical tissues and applying these refined tools to address fundamental questions in plant development, physiology, and stress responses [18]. Continued innovation in probe chemistry, tissue processing, and data integration is essential to surmount plant-specific barriers [18].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Low Cell Viability Affecting Data Quality

- Potential Cause: Enzymatic protoplast isolation damaging plant cells.

- Solution: Optimize digestion time and enzyme concentrations; include viability-enhancing reagents in isolation buffers.

- Prevention: Monitor viability throughout protoplast isolation process; use gentle centrifugation speeds.

Problem: High Ambient RNA Contamination

- Potential Cause: Cell lysis during sample preparation releasing RNA into solution.

- Solution: Implement computational background correction tools; use protocols designed for fixed cells.

- Prevention: Optimize handling to minimize cell stress; use viability-preserving buffers.

Problem: Low Gene Detection Sensitivity

- Potential Cause: Low RNA content due to plant cell vacuolization.

- Solution: Implement nuclear sequencing; use full-length transcript protocols; increase sequencing depth.

- Prevention: Isolate cells during active growth phases; use amplification strategies with lower bias.

Problem: Low Single-Cell Encapsulation Efficiency

- Potential Cause: Poisson distribution limitations in random encapsulation.

- Solution: Apply inertial focusing to evenly space cells before encapsulation, improving efficiency to >77% [25].

- Prevention: Use cell concentration optimization; consider size-based droplet separation methods.

Essential Reagents and Research Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Droplet-Based scRNA-seq

| Reagent/Kit | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Barcoded Gel Beads | Unique cellular mRNA labeling | 10× Genomics Chromium beads contain ~3 million oligonucleotides/bead [22] |

| Template Switch Oligo (TSO) | Enhances cDNA synthesis efficiency | Enables cDNA synthesis independent of poly(A) tails [22] |

| Permeabilization Reagents | Enable cellular access for probes | Critical for plant cells with rigid walls; concentration requires optimization [18] |

| CRISPR-based rRNA Depletion Probes | Reduce ribosomal RNA contamination | Dramatically decreases rRNA percentage (83% to 32%) [20] |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Correct for PCR amplification bias | Enable absolute transcript counting; essential for quantitative analysis [18] [22] |

| Partitioning Oil/Surfactants | Stabilize emulsion droplets | Lower surfactant concentrations yield higher cell viability [26] |

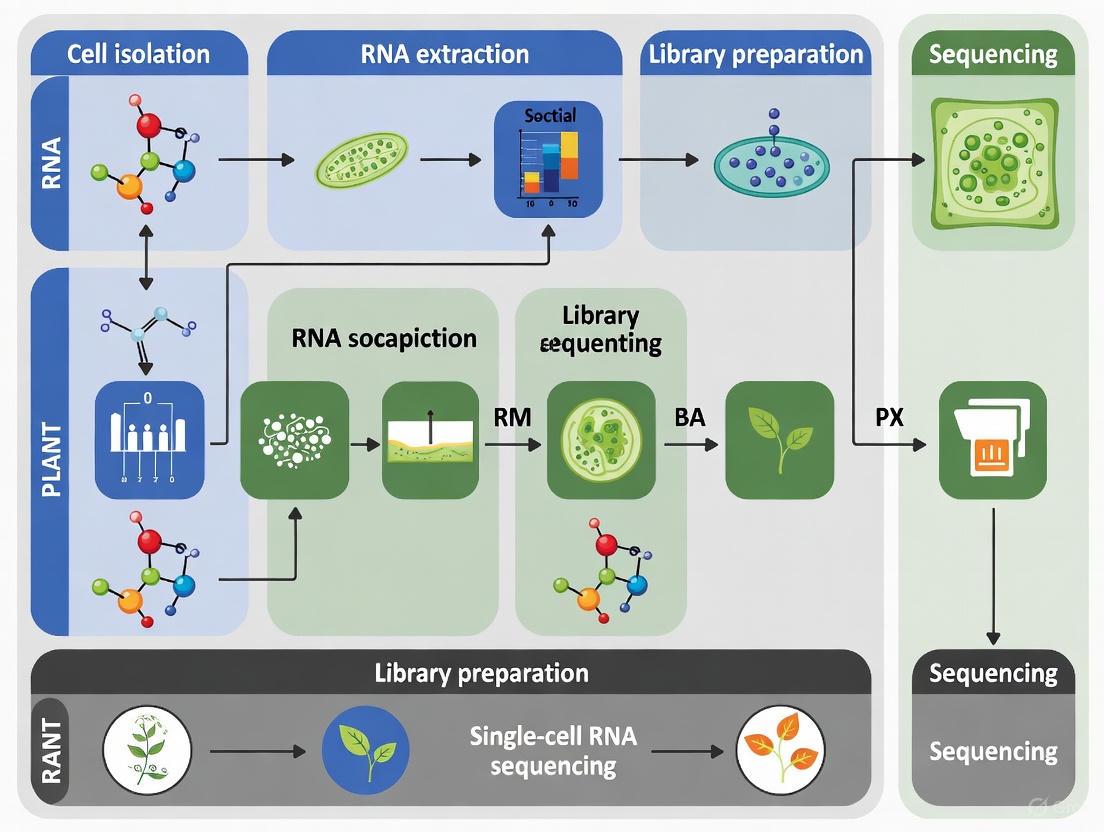

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Comprehensive scRNA-seq Workflow for Plant Research

Diagram 2: Combinatorial Barcoding Enables Massive Throughput

The evolution from low-throughput sorting to high-throughput droplet methods represents one of the most significant technological advancements in single-cell transcriptomics. For plant researchers, these technologies offer unprecedented opportunities to explore cellular heterogeneity in development, stress responses, and host-pathogen interactions at previously unimaginable resolutions. Current droplet-based systems already enable the profiling of thousands to millions of individual cells, with continuous improvements in capture efficiency, molecular sensitivity, and cost-effectiveness [22].

The future of single-cell technologies in plant research lies in several promising directions. First, the integration of spatial transcriptomics with single-cell approaches will bridge the critical gap between single-cell resolution and tissue context, particularly important for understanding plant developmental processes [18] [22]. Second, the application of multimodal omics technologies—simultaneously capturing transcriptomic, epigenomic, and proteomic information from the same cells—will provide more comprehensive understanding of plant cellular regulatory mechanisms [22]. Third, continued innovation in microfluidic designs, such as the NOVAsort system with its dramatically reduced false positive rates, will further enhance the accuracy and efficiency of single-cell analyses [24].

For plant science to fully benefit from these technological advancements, method adaptation must address plant-specific challenges including cell wall digestion, vacuole content management, and specialized protoplast isolation protocols. The ongoing development of plant-optimized workflows and computational tools tailored to plant genomes will undoubtedly unlock new frontiers in understanding plant biology at single-cell resolution.

Single-cell transcriptomics has revolutionized our understanding of cellular heterogeneity in complex plant tissues. However, plant researchers face a unique dilemma: choosing between single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq). This technical guide addresses the critical challenges and considerations for selecting the appropriate method based on your experimental goals, plant species, and tissue type.

The fundamental challenge in plant single-cell analysis stems from the rigid cell wall, which complicates the isolation of intact, viable protoplasts for scRNA-seq [18] [27]. While scRNA-seq profiles the complete transcriptome from entire cells, snRNA-seq sequences RNA primarily from nuclei, offering distinct advantages for certain applications and difficult-to-dissociate tissues [27] [28]. This resource provides a comprehensive technical comparison, troubleshooting guide, and experimental framework to empower your plant single-cell research.

Technical Comparison: scRNA-seq vs. snRNA-seq

Table 1: Comprehensive comparison of scRNA-seq and snRNA-seq for plant research

| Feature | scRNA-seq | snRNA-seq |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Input | Protoplasts (cells without walls) | Isolated nuclei [27] [28] |

| Tissue Compatibility | Tissues amenable to protoplasting (e.g., Arabidopsis leaves, roots) | Tissues difficult to dissociate (e.g., woody species, storage organs), frozen samples [27] [29] |

| Transcript Coverage | Full-length or 3'/5' enriched; captures both nuclear and cytoplasmic mRNA [30] | Primarily nuclear RNA; includes unspliced/pre-mRNA [28] |

| Key Advantages | • Captures complete cellular transcriptome• Higher detected genes per cell (complexity)• Standardized protocols for compatible tissues | • Bypasses protoplasting stress responses• Applicable to hard-to-dissociate tissues and frozen archives• Reduces cellular stress biases [27] [28] |

| Major Limitations | • Protoplasting induces stress responses & alters gene expression• Cell wall digestion biases against certain cell types• Not suitable for all plant species/tissues | • Lower transcriptional complexity (misses cytoplasmic RNAs)• Potential for more immature RNA sequences• Nuclear isolation challenges in some tissues [27] [28] |

| Ideal Applications | • Studies requiring full transcriptome coverage• Cellular processes involving cytoplasmic mRNAs• Tissues that yield healthy, intact protoplasts | • Cellular taxonomy of complex tissues• Frozen/biobanked samples• Species/tissues resistant to protoplasting [14] [27] [28] |

Experimental Workflow Diagrams

scRNA-seq Workflow for Plants

Diagram 1: scRNA-seq Workflow for Plants. This workflow begins with tissue collection and enzymatic protoplasting to remove cell walls, followed by single-cell isolation, library preparation, and sequencing. Critical points where failures often occur are highlighted in yellow.

snRNA-seq Workflow for Plants

Diagram 2: snRNA-seq Workflow for Plants. This workflow starts with tissue homogenization and nuclear isolation, bypassing protoplasting. The green node highlights the key advantage of using frozen samples.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

Method Selection & Experimental Design

Q1: When should I choose snRNA-seq over scRNA-seq for my plant research? Choose snRNA-seq when: (1) working with tissues difficult to digest into protoplasts (e.g., woody species, mature leaves); (2) using frozen or archived samples; (3) studying cell types sensitive to protoplasting stress; or (4) aiming to reduce technical artifacts from cell wall digestion [27] [28]. For example, a recent Arabidopsis life cycle atlas successfully employed snRNA-seq across 10 developmental stages, demonstrating its applicability for comprehensive studies [14].

Q2: Can I combine both approaches in a single study? Yes, integrated approaches are powerful. For instance, paired snRNA-seq and spatial transcriptomics enabled confident annotation of 75% of cell clusters in the Arabidopsis atlas by validating cluster markers in their native spatial context [14]. This integration overcomes annotation challenges and provides spatial validation of cell-type identities.

Protocol Optimization & Troubleshooting

Q3: How can I improve nuclear isolation for snRNA-seq from challenging plant tissues? Optimize homogenization buffers (e.g., sucrose concentration 250-320 mM with nonionic detergents like Triton X-100) [28]. Include RNase inhibitors throughout the process and perform density gradient centrifugation for purification. Validate nuclear integrity and RNA quality microscopically and with bioanalyzer before proceeding [28].

Q3: My protoplasts show stress responses during scRNA-seq. How can I minimize this?

- Reduce digestion time to the minimum required

- Use optimized enzyme cocktails specific to your plant species and tissue type

- Include stress-mitigating compounds in digestion buffers

- Process controls immediately after protoplast isolation to minimize ex vivo stress [27]

Q4: What are the key bioinformatic considerations for analyzing plant snRNA-seq data? For snRNA-seq, ensure your pipeline includes intronic reads during alignment and counting, as over 50% of nuclear RNAs are typically intronic compared to 15-25% in total cellular RNA [28]. Adjust quality control metrics since mitochondrial reads (common in scRNA-seq) are largely absent.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key reagents and materials for plant single-cell transcriptomics

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Wall Digesting Enzymes (Cellulase, Pectinase, Macerozyme) | Protoplast isolation for scRNA-seq | Concentration and combination must be optimized for specific plant species and tissue type [27] |

| Nuclear Isolation Buffers | Release intact nuclei while preserving RNA | Typically contain isotonic sucrose (250-320 mM) and nonionic detergents; commercial kits available (e.g., 10× Genomics) [28] |

| RNase Inhibitors | Prevent RNA degradation during isolation | Critical for both protocols, especially during nuclear isolation and protoplasting [28] |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Barcode individual molecules for quantitative analysis | Essential for accurate transcript counting in both methods; included in most modern protocols [30] |

| Barcoded Beads (10× Genomics, BD Rhapsody) | Capture and barcode single cells/nuclei | Platform choice affects cell throughput, cost, and compatibility with tissue types [30] [27] |

| Density Gradient Media (Iodixanol, Sucrose) | Purify nuclei from cellular debris | Particularly important for tissues with high starch or secondary metabolite content [28] |

The choice between scRNA-seq and snRNA-seq represents a critical strategic decision in plant single-cell research. While scRNA-seq provides comprehensive transcriptome coverage including cytoplasmic mRNAs, snRNA-seq offers access to challenging tissues and reduces cellular stress artifacts [27] [28].

For most applications with amenable tissues, scRNA-seq remains the gold standard for complete transcriptome characterization. However, snRNA-seq has proven exceptionally valuable for large-scale atlas projects [14] and studies of difficult-to-dissociate tissues. The emerging best practice involves integrating both approaches with spatial transcriptomics to validate findings within tissue context and build comprehensive understanding of plant cellular biology [14] [27].

As technologies advance, both methods will continue to evolve, offering plant researchers unprecedented resolution to explore development, environmental responses, and cellular differentiation with increasing precision and biological relevance.

From Theory to Practice: scRNA-seq Protocols and Breakthrough Applications in Botany

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized biological research by allowing scientists to profile gene expression at the level of individual cells. This is particularly powerful for understanding complex plant systems, where cellular heterogeneity plays a crucial role in development and environmental responses. Two predominant methodologies have emerged: full-length transcript protocols like Smart-seq2 and 3'-end counting protocols such as those implemented by the 10x Genomics Chromium system. Choosing between these approaches involves careful consideration of your research goals, and in the context of plant biology, this decision is further complicated by unique challenges such as cell walls and the presence of diverse cell types. This guide provides a technical comparison and troubleshooting resource to help you successfully navigate these challenges.

Technical Comparison: Smart-seq2 vs. 10x Genomics

The table below summarizes the core technical specifications and performance characteristics of the two platforms to guide your initial selection [31] [32] [33].

| Feature | Smart-seq2 (Full-Length) | 10x Genomics (3'-End Counting) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Technology | Plate-based, full-length transcript sequencing | Droplet-based, 3' end counting with UMIs |

| Throughput | Lower (tens to hundreds of cells) [31] | High (thousands to tens of thousands of cells) [31] [4] |

| Sensitivity | Higher genes/cell (especially for low-abundance transcripts) [31] [34] | Lower genes/cell, but higher molecular capture efficiency [31] |

| Transcript Coverage | Uniform coverage across the entire transcript [35] [34] | Focused on the 3' end of transcripts [35] |

| UMIs | No (protocol does not natively include UMIs) [35] [36] | Yes (essential for accurate digital counting and correcting PCR bias) [31] [33] [35] |

| Key Strengths | Detection of splice isoforms, SNVs, and allelic expression; superior for low-abundance transcripts [31] [34] | Identification of rare cell types; scalable for large experiments; robust cell calling with EmptyDrops algorithm [31] [33] [4] |

| Primary Limitations | No strand specificity; transcript length bias; cannot correct for PCR amplification bias [35] [36] | "Dropout" effect for low-expression genes; lower sequencing depth per cell [31] |

| Ideal Use Cases | Isoform discovery, detailed characterization of specific cell types, eQTL mapping | Cell atlas construction, rare cell type discovery, developmental trajectory inference |

Experimental Workflow Diagrams

Full-Length Protocol (Smart-seq2) Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the key steps in a typical full-length scRNA-seq protocol.

3'-End Counting Protocol (10x Genomics) Workflow

The diagram below outlines the core process for droplet-based, 3'-end counting scRNA-seq.

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting

Q1: My protoplast preparation from plant tissue yields very few cells or poor viability. What are my options? This is a common challenge in plant scRNA-seq. The rigidity of plant cell walls requires enzymatic digestion, which can induce stress responses and damage cells [37] [38].

- Solution A (Optimize Protoplasting): Systematically optimize the enzyme cocktail, concentration, and digestion time for your specific plant species, tissue, and developmental stage. Reducing digestion time can improve viability.

- Solution B (Switch to Nuclei): Use single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) as an alternative. Isolating nuclei is faster, avoids enzymatic stress, and is compatible with frozen tissues, making it suitable for difficult tissues like xylem [37] [38]. Note that this method primarily captures nuclear transcripts and may miss some cytoplasmic RNAs.

Q2: After sequencing with a 10x protocol, my data shows a high percentage of reads mapping to mitochondrial genes. Is this a problem? Yes, a high mitochondrial read percentage often indicates poor cell quality, possibly due to apoptosis or cytoplasmic RNA loss from damaged cells during protoplasting [31] [38].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Check Cell Quality: Re-evaluate your protoplast/nuclei isolation protocol to ensure it is gentle and minimizes stress.

- Benchmark: Note that Smart-seq2 and bulk protocols naturally yield a higher mitochondrial proportion (~30%) due to more thorough membrane disruption, which is not necessarily indicative of poor quality in that context [31].

- Filter in Analysis: In downstream data analysis, you can filter out cells with abnormally high mitochondrial read counts (e.g., >50% for protoplasts) to remove low-quality cells [31].

Q3: For full-length protocols like Smart-seq2, how do I account for PCR amplification bias without UMIs? This is a recognized limitation of the Smart-seq2 protocol. While newer methods like Smart-seq3 incorporate UMIs, if you are using Smart-seq2, you must be aware that your gene counts could be influenced by PCR duplication [35] [34].

- Guidance:

- While some traditional deduplication methods exist, they are often considered over-correction and can reduce power [35].

- For many applications where relative expression levels are compared across cell types, the impact of this bias may be acceptable. However, for absolute quantitative measures, a UMI-based protocol is strongly recommended.

Q4: My 10x experiment did not recover the expected number of cells. What could have gone wrong? Accurate cell counting and concentration measurement before loading are critical for the 10x platform [39].

- Best Practices:

- Use Accurate Counting: Employ automated cell counters or hemocytometers to get precise cell concentration and viability measurements.

- Account for Viability: Ensure you calculate the concentration based on viable cells only.

- Follow Loading Guidelines: Adhere to the recommended loading concentrations (e.g., 700-1200 cells/µl for most 10x v3 kits) to avoid overloading or underloading the chip [39].

- Verify with Software: The Cell Ranger pipeline uses algorithms (OrdMag and EmptyDrops) to distinguish true cells from ambient RNA, which can help recover cells with lower RNA content [33].

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key reagents and their critical functions in scRNA-seq workflows for plant research.

| Reagent / Material | Function | Considerations for Plant Research |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Wall Digesting Enzymes (e.g., Cellulase, Pectolyase) | Digest cell wall to release protoplasts. | The cocktail and concentration must be optimized for each plant species and tissue type to minimize stress-induced transcriptional changes [37] [38]. |

| Barcoded Beads (10x) | Deliver cell barcode and UMI sequences during GEM formation. | Essential for multiplexing thousands of cells. The chemistry is standardized by the manufacturer (e.g., NextGEM vs. GEM-X) [33] [39]. |

| Template Switching Oligo (TSO) | Enables full-length cDNA synthesis in Smart-seq2. | The design (e.g., use of LNA) is crucial for high sensitivity and yield in full-length protocols [32] [34] [36]. |

| Reverse Transcriptase | Synthesizes first-strand cDNA from mRNA templates. | Processive enzymes (e.g., Maxima H-minus in Smart-seq3) improve sensitivity and full-length coverage, especially for long transcripts [34]. |

| Nuclei Isolation Buffer | Lyse cells and stabilize released nuclei for snRNA-seq. | A critical reagent for bypassing protoplasting issues. Must maintain nuclear integrity and RNA quality [37] [38]. |

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized plant biology by enabling researchers to uncover gene expression profiles of individual cell types within complex tissues [40]. However, the success of these advanced transcriptomic techniques is entirely dependent on the quality of the initial sample preparation. This technical support center addresses the critical challenges in protoplast isolation and nuclei isolation for plant single-cell research, providing troubleshooting guides and optimized protocols to ensure reliable results for your experiments.

FAQs: Addressing Common Challenges in Plant Single-Cell Sample Preparation

Q1: What are the primary considerations when choosing between protoplast isolation and nuclei isolation for plant scRNA-seq?

The decision depends on your research goals, plant species, and tissue type. Protoplasts (plant cells with cell walls removed) are ideal for functional genomics, transient gene expression, and CRISPR reagent validation [41] [13]. They offer a complete cellular transcriptome but can experience stress-induced transcriptional changes during isolation. Nuclei isolation is preferred for scRNA-seq of difficult tissues (like leaves with high chloroplast content), frozen samples, or when tissue dissociation is challenging [42] [40]. Nuclei provide more stable transcripts but may lack cytoplasmic mRNAs.

Q2: Why does leaf tissue present unique challenges for nuclei isolation, and how can these be overcome?

Leaf tissue contains abundant chloroplasts that interfere with nuclei isolation. DAPI staining cannot distinguish nuclei from chloroplasts because it also binds to plastid DNA, leading to sorted contamination and an overestimation of nuclei count [40]. An improved protocol utilizes the autofluorescence of chloroplasts during Fluorescent-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) to effectively separate and remove them, resulting in purer nuclei populations and improved alignment rates for scRNA-seq [42] [40].

Q3: How critical is donor plant material for successful protoplast isolation?

Extremely critical. The age and type of donor material significantly impact protoplast yield and viability. For cannabis, the optimal source is 1–2-week-old leaves from in vitro-grown seedlings [43]. For pea, well-expanded leaves from 2–4 week old plants are used [41]. Tissue freshness and growth conditions directly affect cell wall composition and enzymatic digestion efficiency.

Q4: What are the key factors influencing protoplast transfection efficiency?

Polyethylene glycol (PEG)-mediated transfection efficiency depends on multiple optimized parameters. Research on pea protoplasts demonstrated that the highest transfection efficiency (59%) was achieved using 20% PEG concentration, 20 µg plasmid DNA, and 15 minutes of incubation time [41]. Different plant species may require optimization of these parameters.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Low Protoplast Yield or Viability

Table 1: Troubleshooting Low Protoplast Yield or Viability

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low yield | Suboptimal enzyme combination or concentration | Optimize cellulase (1-2.5%) and macerozyme (0-0.6%) concentrations [41]; For tough tissues, add pectolyase (0.05-0.5%) [13] |

| Incorrect osmolarity | Adjust mannitol concentration (0.3-0.6 M) to maintain proper osmotic pressure [41] [13] | |

| Inadequate digestion time | Test enzymolysis duration (2-16 hours) based on tissue type [41] [43] | |

| Low viability | Excessive mechanical damage during isolation | Use gentle shaking (40-50 rpm) during digestion; avoid vigorous pipetting [13] |

| Oxidative stress | Add antioxidants to enzyme and wash solutions [43] | |

| Improper purification | Purify through sucrose or Percoll density gradients to remove debris [41] |

Guide 2: High Chloroplast Contamination in Nuclei Preparations

Table 2: Addressing Chloroplast Contamination in Leaf Tissue Nuclei Isolation

| Problem | Solutions | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Chloroplast co-purification with nuclei | Utilize FACS sorting with gating on chloroplast autofluorescence to exclude them [40] | Significant reduction in chloroplast contamination |

| Avoid harsh detergents that damage nuclear membranes [40] | Preservation of nuclear integrity while removing organelles | |

| Include a low-speed centrifugation step to pellet nuclei while leaving chloroplasts in suspension [40] | Preliminary separation before FACS | |

| Poor RNA quality from nuclei | Work quickly at 4°C to minimize RNA degradation | Higher quality nuclear RNA for sequencing |

| Use RNase inhibitors throughout the isolation process | Improved transcript recovery |

Optimized Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Efficient Protoplast Isolation and Transfection for CRISPR Applications

Based on the optimized protocol for pea (Pisum sativum L.) [41]:

Plant Material: Use fully expanded leaves from 2–4 week old plants grown under controlled conditions.

Enzyme Solution Preparation:

- 20 mM MES (pH 5.7)

- 20 mM KCl

- 10 mM CaCl₂

- 0.1% BSA

- Mannitol (0.3-0.6 M for osmotic balance)

- Cellulase R-10 (1-2.5%)

- Macerozyme R-10 (0-0.6%)

- Filter sterilize before use

Isolation Procedure:

- Remove mid-ribs and cut leaves into 0.5 mm thin strips

- Transfer to enzyme solution (10 ml per 0.5 g tissue)

- Digest in the dark with gentle shaking (40-50 rpm) for 4-16 hours

- Filter through sterile mesh (70-100 µm) to remove debris

- Centrifuge at 100-200 × g for 5 minutes to pellet protoplasts

- Resuspend in W5 solution (154 mM NaCl, 125 mM CaCl₂, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM MES)

- Purify through sucrose or Percoll gradient if needed

PEG-Mediated Transfection:

- Use 20 µg plasmid DNA per transfection

- Employ 20% PEG solution

- Incubate for 15 minutes

- Wash to remove PEG and assess transfection efficiency

Protocol 2: Improved Nuclei Isolation from Leaf Tissue for snRNA-seq

Adapted from the enhanced protocol for maize leaves [40]:

Tissue Preparation:

- Harvest fresh leaf tissue from V5 stage maize plants

- Dissect midsection into 1 cm × 1 cm pieces

- Keep tissue moist and process immediately

Nuclei Extraction Buffer:

- 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4)

- 10 mM NaCl

- 10 mM MgCl₂

- 0.1% Triton X-100

- 1% BSA

- 0.5 mM DTT

- RNase inhibitors

- Adjust osmolarity with sucrose or glycerol

Isolation Procedure:

- Homogenize tissue in cold extraction buffer using a mechanical homogenizer (2-3 pulses)

- Filter homogenate through 30-40 µm cell strainer

- Centrifuge at 500 × g for 5 minutes at 4°C

- Resuspend pellet in nuclei extraction buffer with DAPI staining

Chloroplast Removal via FACS:

- Use FACS with gating on DAPI-positive events

- Apply additional gating to exclude chloroplast autofluorescence

- Sort purified nuclei directly into collection buffer with RNase inhibitors

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Protoplast and Nuclei Isolation

| Reagent | Function | Example Concentrations | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cellulase R-10 | Degrades cellulose cell walls | 1-2.5% [41]; 1.5% [13] | Concentration varies by tissue type |

| Macerozyme R-10 | Digests pectin components | 0-0.6% [41]; 1.5% [13] | Essential for mesophyll tissues |

| Mannitol | Maintains osmotic balance | 0.3-0.6 M [41] [13] | Critical for protoplast integrity |

| Pectolyase Y-23 | Additional pectinase for tough tissues | 0.05% [13] | Use when standard enzymes are insufficient |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Facilitates plasmid DNA transfection | 20% [41] | Molecular weight and concentration affect efficiency |

| MES Buffer | Maintains stable pH during isolation | 20 mM, pH 5.7 [41] | Optimal for enzyme activity |

| BSA | Reduces enzyme toxicity and adsorption | 0.1% [41] [13] | Improves protoplast viability |

Workflow Visualization

Key Optimization Strategies

Strategy 1: Tissue-Specific Enzyme Optimization

The composition and concentration of cell wall-degrading enzymes must be tailored to specific tissues and species. For example, in Toona ciliata, the optimal enzyme combination was determined to be 1.5% Cellulase R-10 and 1.5% Macerozyme R-10 [13], while cannabis protoplast isolation may benefit from the addition of pectolyase [43]. Systematic testing of enzyme combinations using factorial experimental designs can identify optimal conditions for new species or tissue types.

Strategy 2: Managing Stress Responses

Protoplast isolation induces significant stress responses that can alter transcriptional profiles. Transcriptomic analyses of cannabis protoplast cultures revealed activation of oxidative and abiotic stress response markers [43]. Including antioxidants in isolation buffers, maintaining optimal temperatures (22-25°C), and minimizing processing time can reduce stress-induced artifacts in downstream applications.

Strategy 3: Quality Assessment Metrics

Establish rigorous quality control checkpoints:

- Protoplasts: Assess viability using fluorescein diacetate (FDA) staining (>80% viability recommended) and yield (typically 10⁵-10⁷ cells/g tissue) [41] [43]

- Nuclei: Evaluate purity by microscopy and flow cytometry, ensuring minimal chloroplast contamination [40]

- RNA Quality: Verify RNA integrity number (RIN) >8.0 for scRNA-seq applications

Mastering protoplast and nuclei isolation techniques is fundamental to advancing plant single-cell research. By implementing these optimized protocols, troubleshooting guides, and quality control measures, researchers can overcome the significant challenges associated with plant sample preparation. The strategies outlined here provide a pathway to generate high-quality single-cell suspensions that will yield reliable, reproducible results in downstream transcriptomic applications, ultimately accelerating discoveries in plant biology and biotechnology.

Single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized plant developmental biology by enabling researchers to investigate cellular heterogeneity and developmental trajectories at unprecedented resolution. This technical support center addresses the specific challenges plant researchers face when applying scRNA-seq to root and meristem studies, providing troubleshooting guidance and methodological insights to overcome these hurdles and successfully map cell fate decisions.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs): Technical Challenges and Solutions

Q1: What is the main advantage of using scRNA-seq over bulk RNA-seq for studying root development?

Bulk RNA-seq analyzes the transcriptome of a group of cells, providing an average gene expression profile for the entire sample. In contrast, scRNA-seq sequences the genome of individual cells, revealing heterogeneity between cell populations [3]. This is crucial for studying highly organized tissues like the root apical meristem, as it allows for:

- Identification of rare cell types and transitional cell states.

- Reconstruction of continuous differentiation trajectories through pseudotime analysis [44] [3].

- Generation of high-resolution transcriptome atlases that redefine cell identities based on molecular analysis [3].

Q2: My plant cells are large or difficult to protoplast. What alternatives exist for scRNA-seq?

The requirement for single-cell suspension via protoplasting is a major bottleneck in plant scRNA-seq, as it can introduce transcriptional stress responses and is unsuitable for large cells (above 30-50 µm) or certain tough tissues [44]. Two main alternatives are available:

- Single-nucleus RNA-sequencing (snRNA-seq): This method uses isolated nuclei instead of whole cells. It is applicable to any organ or species, including frozen samples, and minimizes the capture biases associated with protoplasting [44]. Studies show that snRNA-seq generally performs equally well as whole-cell methods for sensitivity and cell type classification [44].

- Spatial Transcriptomics: This emerging technology allows for gene expression visualization directly in the tissue context without the need for single-cell dissociation. It is ideal for validating scRNA-seq predictions and studying structure-function relationships [44].

Q3: How can I study a rare cell population without profiling thousands of cells?

While profiling a large number of cells can capture rare states, it is often cost-prohibitive. To increase specificity, you can enrich for your cell population of interest before sequencing. In plants, this is typically achieved by:

- Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS): Using fluorescent protein-tagged reporter lines that mark a specific spatiotemporal domain to sort the desired cells or nuclei (FANS) [44]. This approach has been successfully used to profile specific lineages, such as the sieve element, and the early stages of lateral root formation [44].

Q4: How do I validate findings from my scRNA-seq analysis?

Predictions from scRNA-seq must be experimentally validated due to potential biases from sample preparation and computational analysis [44]. Common validation methods include:

- Reporter Lines: Constructing and analyzing transgenic lines expressing fluorescent proteins under the control of newly identified candidate gene promoters [44] [3].

- In Situ Hybridization (ISH): Visualizing mRNA transcripts directly in tissue sections [44].

- Spatial Transcriptomics: As mentioned above, this technology can be used to spatially map the expression of genes identified in your scRNA-seq dataset [44].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Problems

Table 1: Common scRNA-seq Problems and Solutions in Plant Research

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low cell viability after protoplasting | Over-digestion with enzymes; sensitive cell types | Optimize enzyme concentration and digestion time; consider snRNA-seq [44]. |

| Under-representation of specific cell types | Bias in protoplasting efficiency or cell capture | Use nuclei isolation (snRNA-seq) to minimize capture bias [44] [30]. |

| High background noise in data | Low-quality cells or library preparation issues | Implement rigorous quality control to filter out low-quality cells and multiplets [30]. |

| Inability to resolve rare cell populations | Insufficient sequencing depth or number of cells | Use FACS/FANS to pre-enrich the rare population before sequencing [44]. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Standard Workflow for Plant Root scRNA-seq

The following diagram illustrates the primary steps and key decision points in a standard scRNA-seq workflow for plant roots.

Key Hormonal Pathway in Meristem Cell Fate

The HECATE transcription factors control the timing of stem cell differentiation in the shoot apical meristem by modulating the balance between cytokinin and auxin, two key phytohormones. The following diagram summarizes this regulatory interaction.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Kits for Plant scRNA-seq

| Item | Function | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Isolation | ||

| Protoplasting Enzymes | Digests cell wall to release individual protoplasts. | Cellulase, Pectinase, Macerozyme [44]. |

| Nuclei Isolation Buffer | Extracts nuclei for snRNA-seq. | Suitable for frozen samples and difficult tissues [44]. |

| scRNA-seq Platform | ||

| Droplet-Based Kits | High-throughput capture of single cells/nuclei. | 10x Genomics Chromium; lower cost per cell [30] [3]. |

| Plate-Based Kits | Full-length transcript sequencing. | SMART-Seq2; higher sensitivity for low-abundance genes [30]. |

| Critical Reagents | ||

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Labels individual mRNA molecules to correct for PCR amplification bias. | Essential for accurate transcript quantification [30] [8]. |

| Poly[T] Primers | Reverse transcription primers to selectively capture polyadenylated mRNA. | Minimizes ribosomal RNA contamination [30] [8]. |

Data Interpretation Guide: From Sequences to Trajectories

A major advantage of scRNA-seq in root and meristem research is trajectory inference, which computationally orders cells along a pseudotemporal path to reconstruct differentiation dynamics [44] [3]. The orderly structure of the Arabidopsis root meristem, with cells at all differentiation stages aligned in cell files, makes it exceptionally suitable for this analysis [44].

- Applications: Trajectory analysis has been used to reveal a differentiation gradient in the protophloem [44] and to identify precursor cells that rapidly reprogram during lateral root formation [44].

- Considerations: Successful trajectory analysis requires a sufficient number of cells at each step of the pseudotime and high sequencing depth per cell [44]. For focused studies, generating tissue-specific datasets with higher coverage can be more cost-effective than whole-organ atlases.

Successfully applying scRNA-seq to map cell fate in roots and meristems requires careful planning to overcome plant-specific challenges. By selecting the appropriate cell isolation method (protoplasting vs. nuclei isolation), leveraging enrichment strategies for rare cells, and using robust computational tools for trajectory analysis, researchers can unlock deep insights into the fundamental processes of plant development.

Frequently Asked Questions: Troubleshooting Single-Cell RNA Sequencing in Plants

FAQ 1: Should I use protoplasts or nuclei for my plant scRNA-seq experiment? The choice depends on your research goals and the plant tissue being studied. Protoplasts, isolated by enzymatically digesting the cell wall, capture RNA from both the cytoplasm and nucleus, providing a more comprehensive view of the transcriptome [45]. However, the enzymatic digestion process can itself alter gene expression, and tissues with robust cell walls (like xylem) may be difficult to dissociate, leading to a bias against certain cell types [45]. In contrast, single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) circumvents cell wall digestion, avoiding protoplasting-induced stress responses. This makes it particularly suitable for difficult-to-digest tissues or frozen samples [45]. For studies of soil stress responses, where outer root tissues are critical, note that protoplasting from soil-grown roots can lead to the loss of fragile cell types like root hairs [46].

FAQ 2: My scRNA-seq data from soil-grown roots shows major changes only in outer tissues. Is this expected? Yes, this is a biologically relevant finding. A 2025 study on rice roots revealed that growth in natural soil versus homogeneous gel conditions triggers transcriptional changes predominantly in outer root cell types (epidermis, exodermis, sclerenchyma, and cortex) [46]. Inner stele tissues, such as phloem and endodermis, show relatively minor changes [46]. The differentially expressed genes in outer tissues are often involved in nutrient homeostasis, cell wall integrity, and defence responses, reflecting their direct interface with the soil environment [46].

FAQ 3: How can I integrate spatial information into my single-cell transcriptomics data? Spatial transcriptomics technologies bridge this gap by mapping gene expression data directly onto tissue architecture [11]. Methods include:

- High-Throughput Chip-Based Platforms (e.g., 10X Visium, Slide-seqV2, Stereo-seq): These use barcoded spots on a slide to capture mRNA from tissue sections, preserving spatial coordinates [11].

- In Situ Hybridization Technologies (e.g., MERFISH, seqFISH+): These use iterative imaging with fluorescent probes to detect hundreds to thousands of RNAs directly in fixed tissues [11]. You can use these spatial data to validate the putative cell identities from your scRNA-seq clusters by testing for the spatial expression of identified marker genes [46].

FAQ 4: What are the primary technical challenges for scRNA-seq in plants, and how can I mitigate them? Key challenges and solutions include:

- Cellular Heterogeneity: Plant tissues are composed of highly diverse cell types. ScRNA-seq is specifically designed to resolve this heterogeneity, but careful experimental design and sufficient cell capture numbers (typically 5,000-10,000 cells) are needed to cover rare cell types [45] [3].

- Sample Preparation: The plant cell wall and abundant secondary metabolites can interfere with protoplasting and RNA capture. Using snRNA-seq or fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) for nucleus purification can help overcome these hurdles [45] [11].

- Data Analysis Complexity: Single-cell data requires specialized bioinformatic processing. Utilize established pipelines like Cell Ranger for initial processing, and tools like Seurat or SCANPY for downstream analysis, including clustering, normalization, and cell type annotation [45].

Experimental Protocols for Key Workflows

Protocol 1: Constructing a Single-Cell Transcriptome Atlas from Plant Roots

This protocol outlines the major steps for generating a scRNA-seq reference dataset, adaptable for studying various environmental stimuli [45] [46].

- Plant Growth & Treatment: Grow plants under controlled conditions. For soil stress studies, establish a standardized soil growth regime alongside a gel-based control [46].

- Tissue Harvesting: Harvest root tips (e.g., 1-cm segments encompassing meristem, elongation, and maturation zones).

- Single-Cell Suspension:

- Protoplast Isolation: Digest cell walls using an enzymatic cocktail (e.g., cellulase and pectolyase) to release protoplasts [45] [46].

- Nuclei Isolation (Alternative): For tough tissues or to avoid enzymatic stress, extract nuclei by homogenizing tissue and purifying nuclei via differential centrifugation or FACS [45].

- Library Construction & Sequencing: Use a high-throughput platform (e.g., 10X Genomics). Individual cells/nuclei are encapsulated in droplets with barcoded beads. Within each droplet, cell lysis, reverse transcription, and barcoding of transcripts occur. The resulting cDNA libraries are then sequenced [45].

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Raw Data Processing: Use

Cell Rangeror similar tools to demultiplex sequencing data, align reads to the reference genome, and generate a cell-by-gene expression matrix [45]. - Quality Control & Filtering: Remove low-quality cells (e.g., with high mitochondrial gene percentage or low unique gene counts) and doublets [45].

- Data Integration & Clustering: Integrate multiple datasets to correct for batch effects. Perform PCA, graph-based clustering, and non-linear dimensionality reduction (UMAP/t-SNE) to group transcriptionally similar cells [46].

- Cell Type Annotation: Identify cluster-specific marker genes. Validate these markers using in situ techniques like Molecular Cartography (multiplexed FISH) to confidently assign cell identities [46].

- Differential Expression & Trajectory Analysis: Compare gene expression across conditions or clusters. Use pseudotime algorithms to infer developmental trajectories [3].

- Raw Data Processing: Use

Protocol 2: Identifying Cell-Type-Specific Responses to Soil Compaction

This methodology builds on the foundational atlas to probe a specific environmental stress [46].

- Experimental Setup: Establish two soil conditions: a control and a compacted soil treatment.

- Sample Collection & scRNA-seq: Harvest root tips from both conditions and process them separately through the scRNA-seq workflow (Protocol 1).

- Data Integration and Annotation: Integrate the scRNA-seq data from stressed and control roots. Annotate cell types using the validated marker genes from your reference atlas [46].

- Differential Expression Analysis: Perform statistical tests to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) within each cell type between the control and compacted soil conditions. Use a threshold (e.g., fold change > 1.5, FDR < 0.05) [46].

- Spatial Validation: Select key DEGs identified in inner tissues (e.g., phloem) and validate their stress-induced expression and spatial localization using spatial transcriptomic platforms [46].

- Functional Analysis: Conduct Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis on the cell-type-specific DEGs to uncover biological processes affected by compaction (e.g., cell wall remodelling, hormone signalling) [46].

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details essential materials and their functions for plant scRNA-seq studies.

| Research Reagent | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Cell Wall Digestion Enzymes (e.g., Cellulase, Pectolyase) | Enzymatic degradation of the plant cell wall for protoplast isolation [45]. |

| Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorter (FACS) | High-throughput separation and purification of protoplasts or nuclei based on fluorescence or size [45]. |

| 10X Genomics Chromium Controller | A commercial droplet-based system for high-throughput single-cell RNA sequencing library preparation [45] [3]. |

| Barcoded Beads (10X Genomics) | Oligo-dT coated beads containing cell barcodes and Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) for mRNA capture and labelling within droplets [45]. |

| Seurat / SCANPY | Widely-used R and Python-based software packages, respectively, for the comprehensive analysis of single-cell transcriptomic data [45]. |

| Spatial Transcriptomics Platform (e.g., 10X Visium, Molecular Cartography) | Technologies that preserve the spatial location of RNA molecules within a tissue section, used for validating scRNA-seq findings [11] [46]. |

Table 1: Key Quantitative Findings from a scRNA-seq Study of Rice Roots in Soil [46]

| Metric | Description / Value |

|---|---|

| Total High-Quality Cells | Integrated atlas from gel and soil conditions contained >79,000 cells. |

| Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) | 11,259 DEGs identified when comparing soil-grown to gel-grown roots. |

| Cell-Type-Specific DEGs | 31% of DEGs were altered in only a single cell type or developmental stage. |

| Tissues with Most Changes | Outer root tissues (epidermis, exodermis, sclerenchyma, cortex) showed the highest number of DEGs. |

| Enriched Biological Processes | Nutrient metabolism (phosphate, nitrogen), cell wall integrity, vesicle transport, hormone signalling, defence. |

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathway

ABA-Mediated Root Response to Soil Stress

Single-Cell Transcriptomics Workflow

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) represents a revolutionary advancement in plant molecular biology, enabling the investigation of transcriptional landscapes at an unprecedented resolution. While traditional bulk RNA-seq provides an averaged gene expression profile across thousands of cells, scRNA-seq captures the unique expression signatures of individual cells, revealing cellular heterogeneity, identifying rare cell types, and elucidating developmental trajectories [19]. This technical support center addresses the specific challenges and considerations for applying scRNA-seq to non-model plant species, including crops, woody plants, and horticultural species, which present unique structural and biological constraints compared to model organisms like Arabidopsis thaliana.

Key Experimental Considerations and Workflows

Choosing Between scRNA-seq and snRNA-seq

A critical first step in experimental design is determining whether to profile single cells or single nuclei. The decision hinges on biological questions, tissue characteristics, and species-specific constraints [47].