Plant Biosystems Design: A Research Roadmap for Next-Generation Crop Improvement and Bioengineering

This article presents a comprehensive roadmap for plant biosystems design, an emerging interdisciplinary field that shifts plant science from trial-and-error approaches to predictive, model-driven strategies. Targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational theories, advanced methodologies, and practical applications of designing plant systems. The scope spans from theoretical frameworks like graph theory and mechanistic modeling to cutting-edge tools such as genome editing, synthetic circuits, and multi-omics integration. We address critical challenges in troubleshooting and optimization, including host-microbiome interactions and pathway stability, and highlight validation techniques from computational modeling to field trials. This roadmap outlines how plant biosystems design can accelerate the development of resilient crops and sustainable plant-based platforms for producing high-value biomolecules, ultimately contributing to food security, biomedical advancement, and a robust bioeconomy.

Plant Biosystems Design: A Research Roadmap for Next-Generation Crop Improvement and Bioengineering

Abstract

This article presents a comprehensive roadmap for plant biosystems design, an emerging interdisciplinary field that shifts plant science from trial-and-error approaches to predictive, model-driven strategies. Targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational theories, advanced methodologies, and practical applications of designing plant systems. The scope spans from theoretical frameworks like graph theory and mechanistic modeling to cutting-edge tools such as genome editing, synthetic circuits, and multi-omics integration. We address critical challenges in troubleshooting and optimization, including host-microbiome interactions and pathway stability, and highlight validation techniques from computational modeling to field trials. This roadmap outlines how plant biosystems design can accelerate the development of resilient crops and sustainable plant-based platforms for producing high-value biomolecules, ultimately contributing to food security, biomedical advancement, and a robust bioeconomy.

Theoretical Foundations and Core Principles of Plant Biosystems Design

Within the framework of plant biosystems design, a paradigm shift is underway from traditional, empirical plant improvement strategies toward innovative approaches based on predictive models of biological systems [1]. This shift is critical to address the ever-increasing demands for food, biomaterials, and sustainable energy in the face of a rapidly growing global population [1] [2]. A central challenge in this endeavor is the inability to causally link genotype to phenotype, which involves complex mappings from genetic sequence to kinetic parameters, from kinetic parameters to biochemical system phenotypes, and from biochemical phenotypes to organismal phenotypes [3]. Mechanistic modeling, which integrates principles of mass conservation with sophisticated flux analysis techniques, provides a powerful theoretical and computational framework to address this grand challenge. By enabling a quantitative and predictive understanding of how genetic perturbations propagate through metabolic and regulatory networks to influence observable traits, mechanistic modeling serves as a cornerstone for the rational design of plant biosystems [3] [4]. This guide details the core theories, methodologies, and applications of these approaches, providing researchers with the tools to accelerate the engineering of improved and novel plant phenotypes.

Theoretical Foundations: From Genotype to Phenotype

The journey from genotype to phenotype involves traversing multiple mechanistic layers. The Phenotype Design Space (PDS) framework offers a rigorous, quantitative theory to navigate these layers by focusing on the mapping of kinetic parameters to biochemical system phenotypes [3].

The Mapping Problem in Plant Biosystems Design

The causal linking of genotype to phenotype involves at least three essential mappings [3]:

- Genetic sequence to kinetic parameters: This mapping deals with how changes in DNA sequence affect the functional properties (e.g., catalytic rate, binding affinity) of the encoded proteins.

- Kinetic parameters to biochemical phenotypes: This involves understanding how the kinetic parameters of individual molecular processes collectively determine the emergent, system-level functions of a biochemical network (e.g., oscillatory behavior, bistability).

- Biochemical phenotypes to organismal phenotypes: This most complex mapping connects the behavior of intracellular networks to observable organismal traits, such as growth rate, architecture, and stress resilience.

The PDS framework addresses the second mapping by providing a mathematically rigorous definition of phenotype based on biochemical kinetics, enabling the enumeration of the full phenotypic repertoire a system can theoretically access, and functionally characterizing each phenotype independent of its context-dependent selection [3].

The Role of Mass Conservation

Mass conservation is a fundamental physical principle that provides critical constraints for inferring and validating metabolic networks. In the context of metabolic network reconstruction from mass spectrometry data, the requirement that putative chemical reactions must conserve mass serves as a powerful filter to eliminate false-positive interactions [5]. This is leveraged by algorithms like ARACNE-MC (Mass Constrained), which prunes a list of statistically suggested metabolic reactions by retaining only those that satisfy mass conservation within a defined tolerance [5]. This integration of statistical dependency with physical law significantly enhances the reliability of inferred network structures.

Methodological Approaches in Metabolic Network Modeling

Several mathematical modeling approaches have been established to quantify and predict the flow of metabolites (flux) through metabolic networks. The table below summarizes the primary methods used in plant studies.

Table 1: Key Methodologies in Metabolic Network Flux Analysis

| Method | Core Principle | Data Requirements | Key Applications in Plants | Primary Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Uses linear programming to predict flux distributions in a genome-scale metabolic network at steady-state, optimizing a biological objective (e.g., biomass). | Genome-scale metabolic model, exchange fluxes. | Prediction of biomass yield, analysis of photorespiration, modeling C4 metabolism. | [4] |

| 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C MFA) | Fits a metabolic network model to steady-state isotope labeling patterns from 13C-tracer experiments to quantify intracellular fluxes. | Network stoichiometry, atom mapping, extracellular fluxes, MS/NMR isotopomer data. | Quantification of central carbon metabolism fluxes in seeds, leaves, and roots. | [6] |

| Isotopically Non-Stationary MFA (INST-MFA) | Extends 13C MFA by modeling the time-dynamics of isotope labeling before steady state is reached, providing a snapshot of flux in shorter timescales. | Time-series isotope labeling data, network model, extracellular fluxes. | Mapping carbon partitioning in Arabidopsis leaves under high light, analysis of photosynthetic flux. | [4] [6] |

| Kinetic Modeling | Uses ordinary differential equations (ODEs) to describe the temporal changes in metabolite concentrations based on enzyme kinetics and regulatory rules. | Enzyme kinetic parameters (Vmax, Km), initial metabolite concentrations. | Elucidation of regulatory mechanisms in monolignol biosynthesis; modeling circadian clock dynamics. | [3] [4] |

Workflow for Mechanistic Flux Analysis

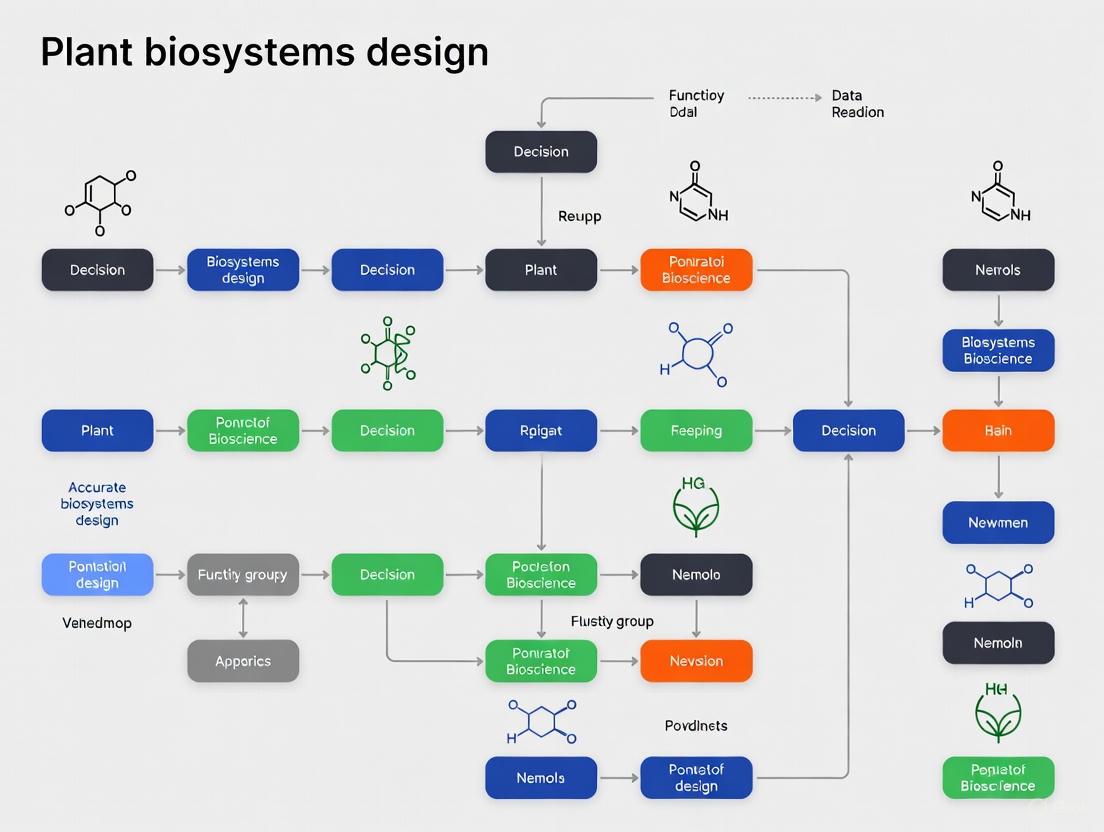

A generalized workflow for applying these methods, particularly MFA, involves several key stages. The process below outlines the pathway from experimental design to model validation and biological insight.

Figure 1: Generalized workflow for Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA), integrating experimental and computational steps.

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Protocol: INST-MFA for Analyzing Photosynthetic Carbon Partitioning

This protocol is adapted from studies investigating in vivo regulation of photoautotrophic metabolism in Arabidopsis [4] [6].

1. Experimental Design and Plant Growth

- Grow Arabidopsis thaliana plants under controlled environmental conditions (light, temperature, humidity).

- Subject plants to the experimental condition of interest (e.g., high light acclimation).

2. 13CO2 Labeling and Sampling

- Transfer plants to a custom-built labeling chamber.

- Rapidly introduce 13CO2 into the chamber atmosphere. The labeling pulse should be short (seconds to minutes) to capture non-steady-state dynamics.

- Collect leaf samples rapidly (e.g., using a freeze-clamp apparatus) at multiple time points after the initiation of labeling (e.g., 0, 10, 20, 40, 60, 120 seconds). Immediately quench metabolism by submerging samples in liquid nitrogen.

3. Metabolite Extraction and Analysis

- Grind frozen tissue to a fine powder under liquid nitrogen.

- Extract polar metabolites using a methanol:water:chloroform solvent system.

- Derivatize extracted metabolites (e.g., using MSTFA for trimethylsilylation) to enhance volatility for GC-MS analysis.

- Analyze derivatized samples using Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS). Measure the mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) of key intermediates in central carbon metabolism (e.g., glycolytic intermediates, pentose phosphate pathway metabolites, TCA cycle intermediates).

4. Computational Flux Estimation

- Construct a stoichiometric model of the photosynthetic network, including the Calvin-Benson cycle, photorespiration, glycolysis, and TCA cycle. Include atom transition information for each reaction.

- Formulate the system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) that describe the time-dependent change in the MID of each metabolite.

- Use a non-linear least-squares optimization algorithm (e.g., Levenberg-Marquardt) to find the set of metabolic fluxes that minimizes the difference between the simulated MIDs and the experimentally measured MIDs across all time points.

- Perform statistical analysis (e.g., Monte Carlo sampling) to estimate the confidence intervals for the calculated fluxes.

Protocol: Reverse Engineering Metabolic Networks with ARACNE-MC

This protocol is used for the computational inference of metabolic reaction networks from mass spectrometry-based metabolomic data [5].

1. Data Preparation

- Obtain a dataset of metabolite abundances (e.g., from LC-MS or GC-MS) across multiple samples (e.g., different perturbations, time points, or genotypes). The dataset should include the measured mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) for each metabolite peak.

- Pre-process the data: perform peak alignment, normalization, and missing value imputation.

2. Conforming Reaction Identification

- For the list of detected metabolites, calculate their putative molecular masses from the m/z values (accounting for adducts and ionization).

- Generate a list of all possible metabolic reactions from a set of allowed templates (e.g., 1x1: A -> B; 1x2: A -> B + C; 2x2: A + B -> C + D).

- Apply the mass conservation constraint: retain only those template reactions where the sum of masses on the left side equals the sum of masses on the right side within a specified tolerance (e.g., ɛ = 10−4). These are the "conforming reactions."

3. Statistical Dependency Analysis

- Calculate the mutual information (MI) for every pair of metabolites from their abundance profiles across the samples.

- Apply the Data Processing Inequality (DPI) from the ARACNE algorithm to prune the MI network, eliminating edges (statistical dependencies) that are likely indirect.

4. Reaction Inference

- ARACNE-MC1: Score each conforming reaction from Step 2 by counting how many of the pairwise interactions among its reactant and product metabolites are supported by the ARACNE-pruned MI network. Retain reactions above a defined threshold.

- ARACNE-MC2 (Recommended): To avoid overcounting, rank all conforming reactions by the cumulative MI of their constituent interactions. An interaction is assigned to support only the strongest reaction it belongs to.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Mechanistic Modeling

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Application Example | Primary Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Substrates (e.g., 13CO2, [U-13C]-Glucose) | Tracer molecules that enable tracking of carbon flow through metabolic pathways. | Quantifying photosynthetic flux and carbon partitioning in leaves. | [6] |

| Design Space Toolbox (DST3) | A software toolbox that automates the analysis of biochemical systems using the Design Space/PDS framework. | Enumerating the repertoire of phenotypic behaviors in a genetic circuit. | [3] |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GSMs) | Curated in silico reconstructions of an organism's entire metabolic network, used for FBA. | Predicting biomass yield in Arabidopsis or rice under different environmental conditions. | [4] |

| BADDADAN Bioinformatics Tool | A tool that uses machine learning and ODEs to model the dynamics of gene modules in response to stress. | Modeling the temporal gene expression response of Arabidopsis to drought or heat stress. | [7] |

| Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) | Analytical platform for separating, identifying, and quantifying metabolites and their isotopologue distributions. | Measuring mass isotopomer distributions for 13C-MFA and INST-MFA. | [4] [6] |

Visualization of Gene Regulatory Network Inference

Modeling large-scale gene regulatory networks is essential for understanding phenotypic responses. The BADDADAN approach combines machine learning with mechanistic ODE modeling to handle the complexity of genome-wide data, as visualized below.

Figure 2: The BADDADAN workflow for inferring interpretable, dynamic gene regulatory network models from transcriptomic data.

Mechanistic modeling, grounded in mass conservation and advanced flux analysis, provides the critical predictive link between genotype and phenotype that is required for the ambitious goals of plant biosystems design. By moving beyond descriptive correlation to quantitative, causal understanding, these approaches allow researchers to simulate the outcome of genetic perturbations before embarking on costly and time-consuming experimental work. The integration of these methods with emerging technologies—such as machine learning for module identification [7] and synthetic biology for circuit engineering [8]—is poised to further accelerate the design-build-test-learn cycle. As these tools become more sophisticated and accessible, they will empower scientists to tackle grand challenges in food and energy security by systematically designing plant systems with optimized performance and novel functions.

Advanced Tools and Applications: From Genome Editing to Synthetic Biology

Plant biosystems design represents a paradigm shift in plant science, moving from traditional trial-and-error approaches toward innovative strategies based on predictive models of biological systems [1] [9]. This emerging interdisciplinary field seeks to accelerate plant genetic improvement through genome editing, genetic circuit engineering, and even de novo synthesis of plant genomes to address global challenges in food security, biomaterials, health, energy, and environmental sustainability [2]. Within this conceptual framework, multi-omics integration has become indispensable for elucidating the complex biosynthetic pathways of plant natural products (also known as specialized metabolites) [10] [11]. These compounds play invaluable roles in ecological balance, human health, industrial applications, and biodiversity conservation, with many serving as clinically important pharmaceuticals or their precursors [11].

The remarkable chemical diversity of plant specialized metabolites—produced in a lineage-specialized manner across phylogenetic taxa, plant organs, and developmental stages—presents both a challenge and opportunity for biosystems design [11]. Multi-omics technologies generate vast datasets that provide a more comprehensive understanding of plant metabolism, while advances in computational tools, machine learning, and data analytics enable researchers to uncover intricate regulatory networks and identify key components of biosynthetic pathways [11]. This review navigates the evolving landscape of plant biosynthetic pathway elucidation accelerated by innovative multidisciplinary strategies that capitalize on big data and their integration within the plant biosystems design roadmap.

Theoretical Foundation: Multi-Omics in Plant Biosystems Design

The Plant Biosystems Design Framework

Plant biosystems design represents a comprehensive approach to expanding plant potential beyond what traditional breeding and genetic engineering can achieve [1]. It encompasses theories, principles, and technical methods aimed at accelerating plant genetic improvement through cutting-edge technologies like genome editing and genetic circuit engineering [9]. The framework acknowledges that plants are still unable to meet ever-increasing human needs in terms of both quantity and quality, necessitating a step-change in our approach to plant modification [2].

Multi-omics integration serves as a cornerstone technology within this framework by providing the comprehensive datasets necessary for predictive modeling of biological systems [1]. The shift from simple trial-and-error approaches to model-based strategies requires extensive data from genomic, transcriptomic, and metabolomic analyses to build accurate representations of plant metabolic networks [9]. This data-driven approach enables researchers to move beyond isolated component analysis to a systems-level understanding that is essential for effective biosystems design.

Fundamental Principles of Multi-Omics Integration

The integration of genomics, transcriptomics, and metabolomics operates on the principle that biological information flows from genetic blueprint to cellular function through multiple molecular layers [12]. Genomics provides the complete parts list of potential metabolic capabilities, transcriptomics reveals which genetic elements are actively being expressed under specific conditions, and metabolomics delivers the ultimate readout of physiological status and biochemical activity [13] [11]. When correlated, these datasets can reconstruct functional biosynthetic pathways and identify key regulatory points.

Multi-omics research primarily consists of two key methodological approaches: (1) correlation analysis using statistical methods to uncover relationships between biological variables, and (2) correlation analysis based on metabolic pathway exploration that examines the link between gene expression and metabolite production [12]. Both approaches contribute to identifying critical regulatory pathways that connect genetic information with metabolic outcomes, providing essential insights for plant biosystems design.

Core Methodologies for Multi-Omics Integration

Experimental Workflows and Platform Technologies

The multi-omics workflow begins with comprehensive data generation across molecular layers. Genomic sequencing provides the foundational blueprint, with modern technologies enabling highly contiguous genome assemblies that reveal gene clusters and syntenic relationships [11]. Transcriptomics profiles gene expression patterns across tissues, developmental stages, or experimental conditions using RNA sequencing technologies. Metabolomics employs two main analytical platforms: mass spectrometry (MS) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, each with distinct advantages and limitations [13].

MS-based metabolomics is typically preceded by a separation step using liquid chromatography (LC-MS) or gas chromatography (GC-MS) to reduce sample complexity [13]. LC-MS is suitable for detecting moderately polar to highly polar compounds like fatty acids, alcohols, vitamins, organic acids, lipids, and other compounds, while GC-MS detects volatile compounds or those that can be derivatized into volatiles, including amino acids, organic acids, fatty acids, and sugars [13]. NMR spectroscopy offers a nondestructive, highly reproducible technique that requires minimal sample preparation but has lower sensitivity compared to MS [13].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the comprehensive process of multi-omics integration for pathway discovery:

Figure 1: Multi-Omics Integration Workflow for Pathway Discovery

Bioinformatics Processing and Quality Control

Metabolomics data processing involves specific software (e.g., XCMS, MAVEN, or MZmine) for quantitative analysis of compounds [13]. This preprocessing step includes noise reduction, retention time correction, peak detection and integration, and chromatographic alignment [13]. Quality control is essential, with QC samples used to balance analytical platform bias, correct signal noise, and determine metabolite feature variance—features with excessive variance are removed from analysis [13].

Data normalization reduces systematic bias or technical variation to prevent misidentification from disparate input of metabolomics data [13]. Compound identification compares mass spectrometry peak data to authentic standard data through in-house libraries or public databases when necessary [13]. The Metabolomics Standards Initiative (MSI) established criteria for reporting metabolite annotation with four identification levels: identified metabolites (level 1), presumptively annotated compounds (level 2), presumptively characterized compound classes (level 3), and unknown compounds (level 4) [13].

Integration Algorithms and Computational Approaches

Multi-omics integration employs sophisticated computational strategies to extract meaningful biological insights from complex, high-dimensional datasets. These approaches can be categorized into three main types:

Co-expression analysis identifies genes with correlated expression patterns across different conditions, tissues, or developmental stages. Pearson correlation has successfully elucidated pathways for etoposide, colchicine, strychnine, and triterpenes, while self-organizing maps have been applied to vinblastine, ajmaline, camptothecin, and other indole alkaloids [11]. Supervised machine learning approaches have further advanced the discovery of tropane alkaloids, monoterpene indole alkaloids, and benzylisoquinoline alkaloids [11].

Homology-based gene discovery utilizes tools like OrthoFinder and KIPEs to identify evolutionarily related genes that may perform similar metabolic functions across species [11]. This approach has facilitated the elucidation of spiroxindole alkaloid and benzylisoquinoline alkaloid pathways [11].

Genomic proximity and cluster analysis leverages the observation that genes involved in specialized metabolic pathways are often physically clustered in plant genomes, similar to bacterial operons [11]. This organizational principle has streamlined the discovery of complete biosynthetic pathways by identifying coordinately regulated gene neighborhoods.

Data Integration and Visualization Strategies

Pathway Correlation Analysis

Based on metabolic pathways from the KEGG database, pathway correlation diagrams analyze relationships between genes (or proteins) and metabolites involved in the same metabolic pathway [12]. These integrative visualizations employ standardized representations: circles for metabolites, squares for genes or proteins, red coloring for upregulated components, blue for downregulated components, and yellow for elements exhibiting both upregulated and downregulated states [12]. This visualization approach enables researchers to quickly identify coordinated changes across molecular layers and hypothesize about regulatory relationships.

Pathway joint enrichment plots provide statistical support for integrated analyses through bar charts or bubble charts displaying pathways jointly enriched in both omics datasets [12]. Bar charts show p-values of enrichment significance with different colors representing metabolomics (red) and transcriptomics (green) data [12]. Bubble charts present five-dimensional information through x-y coordinates, color gradient, shape, and size to convey enrichment factors, significance levels, omics types, and differential metabolite/gene counts [12].

Network-Based Integration

The KGML (KEGG Markup Language) interaction network diagram utilizes KGML files from the KEGG database, which encompass relationships of graphical objects within KEGG pathways and information about orthologous genes from the KEGG GENES database [12]. This establishes network relationships between genes, gene products, and metabolites, facilitating systematic investigation of transcriptomics-metabolomics interactions [12]. In these network diagrams, squares represent genes or gene products, circles denote metabolites, diamonds indicate pathway names, with color coding (red for upregulated, green for downregulated) indicating expression or abundance patterns [12].

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual framework for multi-omics data integration and its relationship to biosystems design:

Figure 2: Multi-Omics Data Integration Framework

Experimental Validation and Functional Characterization

Candidate Gene Selection and Validation Pipeline

Following bioinformatic analysis, candidate genes for specific metabolic steps are selected using various criteria including homology to known enzymes, expression profiles correlated with previously elucidated pathway genes, and genomic location relative to known biosynthetic gene clusters [11]. The selected candidate genes are cloned into expression vectors and transformed into heterologous hosts such as Escherichia coli bacteria, Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast, or Nicotiana benthamiana tobacco for functional validation of recombinant proteins [11].

Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression in N. benthamiana has particularly accelerated functional characterization of plant biosynthetic enzymes in recent years [11]. Compared to heterologous expression in E. coli or yeast, this approach allows rapid, simultaneous co-expression of multiple metabolic genes with significantly less effort in engineering and optimizing cloning platforms [11]. This high-throughput capability aligns with the accelerated discovery goals of plant biosystems design.

In Planta Validation Techniques

After biochemical characterization in heterologous systems, putative genes typically undergo in planta validation using techniques such as virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) or RNA interference (RNAi) to confirm function and establish physiological relevance [11]. These approaches provide critical evidence that bioinformatic predictions and heterologous expression results accurately reflect native biological functions in the source plants.

Advanced techniques including single-cell sequencing and MS imaging are increasingly being applied to validation studies, providing higher spatial resolution to metabolic studies [10] [11]. These technologies enable researchers to resolve metabolic processes at the level of specific cell types, individual cells, or even organelles, addressing the compartmentalization inherent to plant specialized metabolism [11].

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Multi-Omics Studies

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Sepmentation Techniques | Liquid Chromatography (LC) columns | Separation of moderately polar to polar compounds prior to MS analysis [13] |

| Gas Chromatography (GC) columns | Separation of volatile compounds or those derivatized into volatiles [13] | |

| Mass Spectrometry | LC-MS systems | High-resolution identification and quantification of metabolites [13] |

| GC-MS systems | Analysis of volatile metabolite compounds [13] | |

| Bioinformatics Tools | XCMS, MAVEN, MZmine | Metabolomics data preprocessing and peak analysis [13] |

| OrthoFinder, KIPEs | Homology-based gene family analysis and identification [11] | |

| Heterologous Expression Systems | Escherichia coli | Prokaryotic expression system for enzyme characterization [11] |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Yeast expression system for pathway reconstitution [11] | |

| Nicotiana benthamiana | Plant transient expression system for multi-gene co-expression [11] |

Table 2: Key Computational Tools for Multi-Omics Data Analysis

| Tool Category | Representative Tools | Primary Function | Applications in Pathway Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Co-expression Analysis | Pearson correlation, Self-organizing maps | Identify genes with correlated expression patterns | Elucidation of etoposide, colchicine, vinblastine pathways [11] |

| Homology-Based Discovery | OrthoFinder, KIPEs | Identify evolutionarily related genes with similar functions | Spiroxindole alkaloid, benzylisoquinoline alkaloid pathways [11] |

| Pathway Databases | KEGG, MetMap | Reference metabolic pathways for integration analysis | Multi-omics association studies and pathway correlation diagrams [12] |

| Machine Learning Approaches | Supervised ML algorithms | Predictive modeling of gene functions in metabolism | Tropane alkaloid, monoterpene indole alkaloid biosynthesis [11] |

Case Studies in Plant Natural Product Biosynthesis

High-Value Pharmaceutical Compounds

Substantial progress has been made in elucidating complete biosynthetic pathways for high-value plant natural products with pharmaceutical applications. Notable successes include the complete elucidation of pathways for noscapine, morphine, vinblastine, colchicine, strychnine, saponin adjuvants, and limonoids [11]. The majority of these discoveries have occurred in the past decade, accelerated by increasingly abundant plant omics data and powerful computational tools [11].

For example, studies of the strychnine biosynthetic pathway in Strychnos nux-vomica used previously elucidated steps of geissochizine oxidation as starting points for discovery [11]. Based on chemical logic predicting decarboxylation, oxidation, and reduction steps through the known strychnos alkaloid norfluorocurarine, candidate enzymes were effectively selected and the complete pathway was successfully reconstituted [11]. Similarly, the antimalarial drug precursor artemisinic acid has been produced in engineered yeast through heterologous expression of plant biosynthetic genes, demonstrating the application potential of elucidated pathways [10].

Crop Improvement and Sustainable Production

Multi-omics approaches have also been successfully applied to improve understanding of metabolic pathways in crop plants, facilitating targeted breeding or engineering for enhanced nutritional quality, flavor, and stress resistance. For instance, rewiring of the fruit metabolome in tomato breeding has been guided by multi-omics analyses, leading to improved flavor profiles [10]. Similarly, understanding the mechanism of red light-induced melatonin biosynthesis has enabled engineering of melatonin-enriched tomatoes with potential health benefits [10].

These applications demonstrate how multi-omics integration contributes directly to the goals of plant biosystems design by providing the fundamental knowledge needed for targeted genetic improvements. The ability to understand and manipulate complex metabolic traits supports the development of plants with enhanced nutritional value, improved sensory qualities, and increased resilience to environmental challenges.

Future Perspectives and Challenges

Emerging Technologies and Approaches

The field of multi-omics integration continues to evolve rapidly with emerging technologies enhancing both data generation and analysis. Single-cell sequencing technologies are poised to revolutionize plant metabolic studies by resolving heterogeneity within tissues and uncovering cell-type-specific metabolic specializations [10] [11]. MS imaging provides spatial resolution to metabolite detection, enabling researchers to visualize the distribution of specialized metabolites within plant tissues and directly correlate localization with proposed biological functions [10].

Machine learning and artificial intelligence are playing increasingly important roles in processing and interpreting the massive amounts of data generated by multi-omics technologies [11]. These approaches can uncover intricate patterns and relationships within complex datasets that might escape conventional statistical analyses. AI-powered tools are expected to transform biosynthetic pathway discovery by predicting enzyme functions, suggesting missing pathway components, and optimizing experimental designs for more efficient pathway elucidation [11].

Data Management and Collaborative Frameworks

As multi-omics datasets continue to grow in size and complexity, effective data management practices become increasingly critical. The FAIR (Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reusability) data principles are essential for making data sharing more efficient and ensuring that original contributors receive proper citation and recognition when their datasets are reused [11]. These principles facilitate reproducibility and ethical reuse while providing equal access to data-driven innovation, especially important as AI tools increasingly depend on large, well-annotated datasets for training [11].

International collaboration frameworks will be essential for addressing the grand challenges in plant biosystems design [1] [9]. The plant biosystems design research roadmap highlights the importance of coordinated efforts across research institutions, funding agencies, and international boundaries to advance this emerging interdisciplinary area [1]. Such collaborative approaches will accelerate progress by leveraging diverse expertise, sharing resources, and avoiding duplication of efforts.

Social Responsibility and Ethical Considerations

The advancement of plant biosystems design, enabled by multi-omics technologies, comes with important social responsibilities [1] [9]. Researchers must consider strategies for improving public perception, trust, and acceptance of engineered plant systems [1]. Transparent communication about both potential benefits and limitations, thoughtful engagement with diverse stakeholders, and careful consideration of ethical implications will be essential for responsible development and application of these powerful technologies.

Multi-omics integration represents a cornerstone methodology within the broader plant biosystems design research roadmap, providing the comprehensive datasets and analytical frameworks necessary to understand and engineer complex plant metabolic systems. By leveraging genomics, transcriptomics, and metabolomics through sophisticated computational approaches, researchers can accelerate the discovery of plant natural product biosynthetic pathways with applications in medicine, agriculture, and industry. As technologies continue to advance and datasets expand, multi-omics integration will play an increasingly vital role in enabling the predictive models and engineering strategies that define plant biosystems design, ultimately contributing to solutions for global challenges in food security, health, and environmental sustainability.

Plant-microbe interface engineering represents a transformative approach in agricultural biotechnology, leveraging advanced genetic tools to reconfigure the complex interactions between plants and their associated microorganisms. This technical guide examines the core principles and methodologies for engineering these interfaces to enhance disease resistance and establish synthetic symbiosis in crop plants. Framed within the broader context of plant biosystems design research, we present a comprehensive roadmap integrating synthetic biology, systems biology, and computational modeling to accelerate the development of climate-resilient, sustainable agricultural systems. The review synthesizes current advances in microbiome-mediated protection, immune system modulation, and synthetic community assembly, providing researchers with detailed experimental frameworks and reagent solutions for implementing these technologies in both model and crop species.

The plant biosystems design framework represents a paradigm shift from traditional genetic engineering to predictive, systems-level programming of biological functions [14]. This approach considers plants not as isolated entities but as complex holobionts comprising the plant host and its associated microbial communities. Engineering the plant-microbe interface requires sophisticated understanding of the molecular dialogue that governs these interactions, including immune recognition, metabolic exchange, and cross-species signaling [15] [16].

The theoretical foundation for engineering plant-microbe interfaces draws upon graph theory, mechanistic modeling, and evolutionary dynamics to predict how modifications at the genetic level propagate through biological networks to yield desired phenotypes [14]. This enables researchers to move beyond simple gene knock-outs/ins toward comprehensive redesign of signaling circuits and metabolic pathways that shape plant-microbe relationships. When framed within the plant biosystems design roadmap, engineering these interfaces addresses critical challenges in global food security by developing crops with enhanced resilience to pathogens and reduced dependence on chemical fertilizers [14] [17].

Molecular Mechanisms at the Plant-Microbe Interface

Plant Immune Recognition and Microbial Colonization

Plants employ a sophisticated immune perception system that distinguishes beneficial microbes from pathogens through multiple recognition layers. Cell-surface pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) detect microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) to activate pattern-triggered immunity (PTI), while intracellular NLR receptors recognize pathogen effectors to activate effector-triggered immunity (ETI) [16]. The successful colonization by beneficial microbes requires active suppression or avoidance of these immune responses, often through the secretion of specific effectors that interfere with defense signaling [15].

The discrimination of friend from foe at the plant-microbe interface involves intricate signaling mechanisms, including transcriptional and post-translational regulation that enables plants to simultaneously promote symbiosis while activating defenses against pathogens [15]. Beneficial non-symbiotic microbes with biocontrol properties manipulate these recognition systems through mechanisms that are only partially understood. Recent research has revealed that microbial infection strategies extend beyond simple defense suppression to include targeted manipulation of plant signaling networks for nutrient acquisition and niche colonization [15].

Microbiome-Mediated Disease Resistance

The plant microbiome functions as an extended immune system that provides protection through multiple mechanisms. As highlighted in Table 1, beneficial microbial communities confer disease resistance through direct antagonism, resource competition, and induction of systemic resistance in the host plant [16].

Table 1: Mechanisms of Microbiome-Mediated Disease Resistance

| Mechanism | Functional Components | Representative Taxa | Molecular Determinants |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Pathogen Inhibition | Antibiosis, lytic enzymes | Pseudomonas, Bacillus, Streptomyces | Non-ribosomal peptides (e.g., thanamycin), polyketides, chitinases |

| Resource Competition | Nutrient scavenging, spatial exclusion | Chitinophagaceae, Flavobacteriaceae | Iron-chelating siderophores, colonization sites |

| Immune Priming | Induced systemic resistance | Pseudomonas simiae, Bacillus velezensis | Microbe-associated molecular patterns, lipopeptides |

| Metabolic Interference | Quorum quenching | Priestia megaterium | Lactonases, acyl-homoserine lactone degradation |

Disease-suppressive soils represent a natural manifestation of microbiome-mediated protection, where specific microbial communities confer protection to plants against soil-borne pathogens even in the absence of host resistance genes [16]. These soils exhibit two types of suppression: general suppression driven by total microbial biomass, and specific suppression attributed to particular microbial taxa or functional groups [16]. The microbial basis of disease-suppressive soils has been elucidated through multi-omics approaches, revealing enrichment of specific bacterial families including Pseudomonadaceae, Burkholderiaceae, and Actinobacteria [16].

Metabolic Mediators of Plant-Microbe Interactions

Plants actively shape their microbiome through the secretion of root exudates and specialized metabolites that selectively recruit or repel specific microbial taxa [16]. Key metabolic mediators include:

Coumarins: Plant-derived phenolic compounds with antimicrobial properties that selectively inhibit pathogens while tolerating beneficial microbes like Pseudomonas simiae WCS417 [16]. The biosynthesis and excretion of scopoletin is regulated by the transcription factor MYB72 and the β-glucosidase BGLU42 [16].

Benzoxazinoids (BXs): Tryptophan-derived secondary metabolites in cereals that influence root and rhizosphere microbial communities [16]. DIMBOA attracts beneficial Pseudomonas putida KT2440, while MBOA serves as a carbon source for abundant root-associated bacteria [16].

Cucurbitacin B: A bitter triterpenoid in cucurbit plants that selectively enriches Enterobacter and Bacillus populations, providing resistance to Fusarium oxysporum [16].

The "cry for help" phenomenon represents another metabolic mechanism where plants under pathogen attack recruit beneficial microbes to constrain pathogens [16]. For instance, sugar beet plants infected with Rhizoctonia solani selectively enrich bacterial families Chitinophagaceae and Flavobacteriaceae in the root endosphere, which express chitinases, non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPS), and polyketide synthases with antagonistic activity against the pathogen [16].

Engineering Strategies for Enhanced Disease Resistance

Immune Receptor Engineering and Regulatory Network Rewiring

Engineering quantitative disease resistance (QDR) provides broader protection against necrotrophic pathogens compared to gene-for-gene resistance [18]. Recent research in tomato wild relatives revealed that QDR against the necrotrophic fungus Sclerotinia sclerotiorum involves transcriptional network rewiring of a conserved suite of genes rather than complete reprogramming of defense networks [18]. Key findings include:

- Identification of 239 core differentially expressed orthologues across resistant and susceptible genotypes of five tomato species [18]

- NAC transcription factors as central regulators of QDR, with species-specific functions (e.g., NAC29 in S. pennellii) [18]

- Evidence of purifying selection on shared resistance genes, indicating conservation of core defense mechanisms [18]

The engineering of intracellular immune receptors (NLRs) has been advanced through pan-genome and multi-omics approaches that identify novel resistance genes and enable durable resistance trait stacking [15]. These approaches allow for the engineering of synthetic immune receptors with expanded recognition specificities and enhanced signaling capabilities.

Microbiome Engineering and Synthetic Communities

Microbiome engineering approaches leverage natural plant-microbe relationships to enhance disease resistance through multiple strategies:

Synthetic Community (SynCom) Design: Rational assembly of microbial consortia based on functional traits to provide consistent protection against pathogens [19]. SynComs can be designed to complement host genetics by filling metabolic gaps in the plant immune system.

Pathogen-Induced Microbiome Assembly: Harnessing the "cry for help" mechanism by preemptively introducing microbes that respond to pathogen invasion [16]. This approach uses the plant's own signaling systems to activate biocontrol functions when needed.

Quorum Quenching: Disruption of bacterial pathogen communication systems to attenuate virulence without affecting growth, reducing selection pressure for resistance [20]. Quorum quenchers function through competitive inhibition or physical degradation of signaling molecules.

Table 2: Experimental Framework for Microbiome Engineering

| Engineering Approach | Technical Methodology | Validation Assays | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| SynCom Assembly | Culture-based isolation, genomic screening, community modeling | Germ-free plant systems, pathogen challenge assays | Functional redundancy, community stability, host specificity |

| Host-Mediated Microbiome Selection | Genetic engineering of root exudation patterns, directed evolution | Comparative microbiome profiling, metabolomics | Pleiotropic effects, fitness trade-offs, environmental stability |

| In Situ Microbiome Editing | Phage-mediated transduction, conjugative plasmid transfer | Tracking of horizontal gene transfer, functional metagenomics | Regulatory compliance, containment, ecological impact |

Engineering Synthetic Symbiosis for Nitrogen Fixation

The engineering of synthetic symbioses in non-legume crops represents a grand challenge in plant microbiome engineering with profound implications for agricultural sustainability [17]. Current approaches focus on:

Genetic Optimization of Nitrogen-Fixing Bacteria: Engineering Rhizobia and other diazotrophic bacteria for enhanced nitrogen fixation efficiency and expanded host range [17].

Intracellular Delivery Systems: Development of methods for introducing nitrogen-fixing bacteria into plant cells, including protoplast transformation and novel delivery mechanisms [17].

Host Genetic Modifications: Engineering plant genes that facilitate intracellular accommodation of nitrogen-fixing symbionts and formation of specialized compartments [17].

The Stanford Sustainability Accelerator's initiative on synthetic symbioses for nitrogen-fixing crop plants aims to eliminate dependence on nitrogen fertilizers by genetically optimizing nitrogen-fixing bacteria for endosymbiosis and intracellularly delivering these bacteria into plant protoplasts [17]. This multi-component synthetic biology strategy represents the cutting edge of plant-microbe interface engineering.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Engineering Microbiome-Mediated Disease Resistance

Objective: Establish a synthetic microbial community that confers resistance to fungal pathogens in tomato plants.

Materials and Methods:

Beneficial Microbe Isolation and Screening:

- Collect rhizosphere samples from disease-suppressive soils or healthy plants in pathogen-endemic areas

- Serial dilution and cultivation on selective media (e.g., chitin-containing media for chitinolytic bacteria)

- High-throughput in vitro antagonism assays against target pathogens (Fusarium oxysporum, Rhizoctonia solani)

- Genomic sequencing of candidate strains to identify biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) for antimicrobial compounds

SynCom Assembly and Validation:

- Select 5-10 bacterial strains with complementary functional attributes (pathogen inhibition, immune priming, niche competition)

- Optimize strain ratios based on co-culture compatibility assays

- Test SynCom efficacy in gnotobiotic plant systems (Arabidopsis, tomato) under controlled conditions

- Measure disease incidence, pathogen load, and plant growth parameters

Field Evaluation and Ecological Monitoring:

- Conduct small-scale field trials with SynCom treatment versus controls

- Monitor population dynamics of introduced strains using strain-specific qPCR or marker gene sequencing

- Assess impact on native soil microbiomes through 16S/ITS amplicon sequencing

- Evaluate effects on non-target organisms and soil ecosystem functions

Expected Outcomes: Establishment of a defined synthetic community that reduces disease incidence by ≥70% while maintaining yield under pathogen pressure.

Protocol: Engineering Immune Recognition for Broad-Spectrum Resistance

Objective: Create a synthetic immune receptor that confers resistance to multiple fungal pathogens by recognizing conserved effectors.

Materials and Methods:

Effector Screening and Target Identification:

- Heterologously express candidate effectors from related pathogens (Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, Botrytis cinerea)

- Yeast-two-hybrid screening to identify plant proteins targeted by multiple effectors

- Structural analysis of effector-target interactions to identify conserved recognition motifs

Receptor Engineering and Validation:

- Design chimeric NLR receptors incorporating recognition domains for conserved effector structures

- Use Golden Gate cloning to assemble synthetic NLR constructs with modular recognition domains

- Transient expression in Nicotiana benthamiana to test cell death response upon effector delivery

- Stable transformation in tomato and evaluation of resistance phenotypes under controlled environment

Durability and Biosafety Assessment:

- Pathogen evolution assays to assess durability of resistance compared to natural R genes

- Evaluation of potential fitness costs under non-stress conditions

- Testing for auto-activity or unintended immune activation in absence of pathogens

Expected Outcomes: Development of a synthetic immune receptor recognizing 3-5 related fungal pathogens without significant yield penalty.

Visualization of Engineering Approaches and Signaling Pathways

Plant-Microbe Interface Engineering Workflow

Synthetic Symbiosis Engineering for Nitrogen Fixation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Plant-Microbe Interface Engineering

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plant Transformation Systems | Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101, Golden Gate cloning kits | Delivery of synthetic constructs, gene editing components | Modular cloning systems enable rapid assembly of complex genetic circuits |

| Microbial Cultivation Media | Nitrogen-free media for diazotrophs, chitin media for chitinolytic bacteria | Selective isolation of functional microbial taxa | Media formulations can be tailored to select for specific metabolic capabilities |

| Biosensor Systems | Transcription factor-based biosensors, FRET reporters | Real-time monitoring of signaling molecules, metabolites | Enable high-throughput screening of microbial functions and plant responses |

| SynCom Assembly Tools | Biolog EcoPlates, RFU assays for substrate utilization | Functional profiling of microbial communities | Metabolic fingerprinting helps predict functional complementarity in SynComs |

| Gene Editing Components | CRISPR-Cas9/Cas12 systems, base editors, prime editors | Precise modification of plant and microbial genomes | CRISPR systems enable multiplexed editing of gene networks controlling microbe interactions |

| Pathogen Challenge Assays | Fusarium oxysporum, Rhizoctonia solani, Xanthomonas campestris | Evaluation of engineered resistance in controlled conditions | Standardized pathogen stocks and inoculation methods ensure reproducible phenotyping |

| Gnotobiotic Plant Systems | Axenic growth chambers, flow-through systems | Study of plant-microbe interactions without background microbiome | Essential for establishing causal relationships in SynCom function |

The engineering of plant-microbe interfaces represents a frontier in plant biosystems design with significant potential for sustainable agriculture. The integration of synthetic biology, systems biology, and microbiome engineering provides unprecedented opportunities to enhance crop resilience and reduce environmental impacts. Key future research priorities include:

- Development of predictive models that accurately simulate plant-microbe interactions across different environmental conditions [14]

- Advancement of multiplexed genome engineering tools for simultaneous modification of plant and microbial genomes [8]

- Establishment of standardized frameworks for testing and regulatory approval of engineered plant-microbe systems [14]

- Exploration of evolutionary dynamics in engineered plant-microbe relationships to ensure long-term stability and function [14]

As plant biosystems design continues to mature, the strategic engineering of plant-microbe interfaces will play an increasingly central role in developing climate-resilient crops and reducing agriculture's environmental footprint. The technical frameworks and experimental approaches outlined in this review provide a foundation for researchers to advance this promising field toward practical applications in global agriculture.

Plant biosystems design represents a fundamental shift in plant science, moving from traditional, iterative breeding methods toward innovative strategies based on predictive models of biological systems [14] [21]. This field seeks to accelerate plant genetic improvement using advanced genome editing and genetic circuit engineering, with a pinnacle goal of creating novel plant systems through the de novo synthesis of entire plant genomes [14] [9]. The overarching motivation is to address pressing global challenges—such as food security for a growing population, climate change resilience, and sustainable production of biomaterials and energy—that existing plants, even those genetically improved through conventional means, are increasingly hard-pressed to meet [14] [22]. De novo genome synthesis, which involves the computational design and chemical assembly of chromosomes from scratch, is a radical extension of this vision. It promises to unlock ultimate programmability, allowing scientists to design and build plant genomes with bespoke traits unconstrained by the evolutionary history of natural species, thereby expanding the potential of plants to serve human and environmental needs [14].

Theoretical and Computational Foundations

The predictive design of plant biosystems requires a deep, systems-level understanding of biological processes. Several theoretical approaches form the bedrock upon which de novo genome synthesis is built.

Graph Theory for Modeling Biological Systems

A plant biosystem can be conceptualized as a dynamic, multi-scale network. In this model, thousands of nodes (representing genes, RNAs, proteins, and metabolites) are connected by edges (representing their interactions) across four dimensions: three spatial dimensions of structure and one temporal dimension [14]. Graph theory provides the mathematical framework to describe these complex systems. Key structures within these networks include feed-forward loops and feed-back loops, which serve as fundamental building blocks for complex biological functions [14]. Constructing a predictive, genome-scale model of a plant's metabolic and regulatory network remains a primary challenge for the field.

Mechanistic Modeling of Cellular Metabolism

Mechanistic modeling, based on the law of mass conservation, is used to link genes, enzymes, pathways, cells, tissues, and whole-plant organisms [14]. By representing metabolites and reactions as nodes and edges, a metabolic network can be constructed. This network can be analyzed using methods like Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) to predict cellular phenotypes, such as growth or product synthesis rates, under steady-state assumptions [14]. The first genome-scale model (GEM) for a plant was created for Arabidopsis over a decade ago, and today there are more than 35 GEMs for over 10 seed plant species [14]. These models are crucial for in silico testing of designed genetic constructs before physical assembly.

The Role of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning

The integration of big data from multi-omics technologies with advanced computational tools, including machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI), is transforming biosynthetic pathway discovery and genome assembly [11]. For instance, geometric deep learning frameworks like GNNome have been developed for de novo genome assembly [23]. GNNome uses graph neural networks (GNNs) to identify paths in assembly graphs that correspond to reconstructed genomic sequences, achieving contiguity and quality comparable to state-of-the-art algorithmic methods [23]. This AI-based approach facilitates transferability, as new genomes can be easily introduced into the training set, making it a plausible cornerstone for reconstructing complex plant genomes with different ploidy levels.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of GNNome Against State-of-the-Art Assemblers on the CHM13 Genome

| Assembler | Size (Mb) | NG50 (Mb) | NGA50 (Mb) | Complete (%) | QV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GNNome | 3051 | 111.3 | 111.0 | 99.53 | 54.24 |

| Hifiasm | 3052 | 87.7 | 87.7 | 99.55 | 55.86 |

| HiCanu | 3297 | 69.7 | 69.7 | 99.54 | 43.30 |

| Verkko | 3030 | 9.4 | 9.4 | 99.44 | 51.61 |

Table 1 Note: Adapted from results published for the GNNome framework [23]. QV (Quality Value) is a logarithmic measure of consensus accuracy; a higher value indicates a more accurate assembly.

Technical Methodologies for Genome-Scale DNA Assembly and Delivery

The physical construction and integration of large DNA segments is a central technical challenge. Recent breakthroughs in synthetic biology provide a roadmap for achieving this in plants.

1De NovoAssembly of Megabase-Scale DNA

A landmark study, SynNICE, demonstrated the de novo assembly and delivery of a 1.14-megabase (Mb) human DNA locus into mouse embryos, providing a transferable methodology for plant systems [24]. The assembly of such large, highly repetitive DNA sequences requires a sophisticated, multi-stage strategy to overcome the inherent instability and low efficiency of conventional methods.

Combinatorial Assembly Strategy for Megabase DNA: The process involves splitting the target 1.14-Mb sequence into 233 smaller fragments of 5.5-kb, which are chemically synthesized [24]. A three-step combinatorial assembly strategy is then employed in yeast:

- Primary Assembly: The 233 fragments are assembled into 23 larger segments (40-71 kb) using homologous recombination in S. cerevisiae.

- Intermediate Assembly: The 23 segments are assembled into four large constructs (268-331 kb) using protoplast transformation in yeast strains with opposite mating types.

- Final Megabase Assembly: The four large constructs are assembled into the complete 1.14-Mb sequence through two rounds of yeast mating coupled with CRISPR/Cas9-mediated cleavage to linearize acceptor DNA and facilitate homologous recombination [24].

This hierarchical approach avoids the simultaneous assembly of very large fragments and manages highly repetitive sequences more effectively.

Delivery of Large DNA Constructs into Cells

A critical and often limiting step is the delivery of large, intact DNA molecules into totipotent cells. The SynNICE method addresses this by using a Nucleus Isolation for Chromosomes Extraction (NICE) technique [24]. This involves isolating yeast nuclei containing the assembled synthetic chromosome and transferring these nuclei directly into target cells. This shuttle strategy avoids the frequent physical breakage associated with the extraction, purification, and transfection of naked large DNA molecules, thereby preserving the integrity of the megabase-scale construct [24].

Experimental Protocols for Key Processes

Protocol: Combinatorial DNA Assembly in Yeast

This protocol details the assembly of megabase-scale DNA, as used in the SynNICE method [24].

Fragment Synthesis and Preparation:

- Design the target DNA sequence, inserting unique watermark sequences for future identification.

- Split the sequence into 5.5-kb fragments and place a commercial order for chemical synthesis.

- Suspend synthesized fragments in nuclease-free water or TE buffer.

Primary Assembly (40-71 kb Segments):

- Use a chemical transformation protocol for S. cerevisiae strain BY4741.

- For each 40-71 kb segment, co-transform a pool of the respective 5.5-kb fragments with a linearized yeast vector containing homologous arms.

- Plate transformations on appropriate synthetic dropout agar to select for successful clones.

- Validate correct assemblies by colony PCR and Sanger sequencing. For problematic segments (>50 kb), perform an additional assembly step by first assembling 25-kb and 30-kb sub-segments.

Intermediate Assembly (~300 kb Constructs):

- Use protoplast transformation for yeast strains VL6-48α and VL6-48a.

- Assemble the 23 segments into four large constructs (SynA, SynG, SynB, SynC) by co-transforming six large fragments into the yeast strains with opposite mating types.

- Validate constructs using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) and deep sequencing.

Final Megabase Assembly (1.14 Mb):

- First Round: Mate MATα yeast containing SynA and a Cas9 plasmid with MATa yeast containing SynG and a sgRNA plasmid targeting the insertion site. The combined Cas9/sgRNA cleaves SynA and linearizes SynG, allowing SynA to recombine into SynG, creating SynAG.

- Repeat the process for SynB and SynC to create SynBC.

- Second Round: Mate yeast containing SynAG with yeast containing SynBC, using a similar CRISPR-mediated strategy to form the final, complete 1.14-Mb hAZFa sequence.

- Confirm the final assembly by PFGE and whole-sequence validation.

Protocol: Nucleus Isolation and Delivery (NICE)

This protocol describes the transfer of assembled DNA from yeast to target cells [24].

Yeast Nucleus Isolation:

- Grow a culture of yeast harboring the synthetic megabase DNA.

- Harvest cells and convert them to spheroplasts using lytic enzymes (e.g., zymolyase) in an osmotic-stabilizing buffer.

- Lyse spheroplasts gently in a hypotonic buffer with non-ionic detergent to release nuclei.

- Purify intact nuclei via differential centrifugation or density gradient centrifugation.

Delivery into Target Cells:

- Isolate target cells (e.g., plant protoplasts or early embryo cells).

- Use microcell-mediated chromosome transfer (MMCT) or polyethylene glycol (PEG)-mediated fusion to fuse the isolated yeast nuclei with the target cells.

- Culture the fused cells and screen for successful incorporation of the synthetic DNA using PCR specific to the watermark sequences and functional assays.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for De Novo Genome Synthesis

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical DNA Synthesis | Provides the fundamental building blocks for synthetic genes. | Commercial synthesis of 5.5-kb fragments [24]. |

| Yeast Assembly Hosts | Chassis for homologous recombination and assembly of large DNA fragments. | S. cerevisiae strains BY4741, VL6-48α, VL6-48a [24]. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | Enables precise linearization of acceptor DNA during hierarchical assembly. | Used in yeast mating steps for final megassembly [24]. |

| Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE) | Analyzes the size and integrity of large DNA constructs (>100 kb). | Critical for validating assembled megabase DNA [24]. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | AI-based tools for identifying paths in assembly graphs for genome reconstruction. | GNNome framework for de novo genome assembly [23]. |

| Multi-Omics Datasets | Provides foundational data for predictive modeling and gene discovery. | Genomics, transcriptomics, metabolomics data integrated with ML [11]. |

| Plant Protoplasts / Early Embryos | Totipotent recipient cells for the delivery of large synthetic DNA constructs. | Used in SynNICE; analogous plant cells (e.g., embryogenic callus) would be used for plants [24]. |

Integration with the Plant Biosystems Design Roadmap

De novo genome synthesis is a disruptive enabling technology within the broader Plant Biosystems Design Research Roadmap 1.0 [14] [21] [9]. It directly supports the roadmap's goal of moving from "trial-and-error" approaches to "predictive design" [22]. Current research priorities funded by initiatives like the U.S. DOE's Genomic Science Program emphasize engineering plants for bioenergy, bioproducts, and biomaterials, where de novo synthesis could play a transformative role [25]. For example, projects like "BioPoplar" aim to create a tunable chassis for diversified bioproduct production using precision-genome and epigenome-engineering approaches, a goal that would be vastly accelerated by robust de novo genome synthesis capabilities [25]. Furthermore, the study of de novo genes (DNGs)—novel protein-coding genes evolved from non-coding DNA—in plants highlights a natural source of genetic innovation that can inform and inspire the computational design of entirely new genetic parts for synthetic genomes [26]. The ultimate success of this field will also depend on a commitment to social responsibility, including the development of biocontained strains and strategies for improving public perception and acceptance of these groundbreaking technologies [14] [25].

Overcoming Technical and Biological Hurdles in Plant Biosystems Design

Addressing Transformation and Regeneration Barriers Across Species

The ambitious goal of plant biosystems design is to expand the potential of plants through predictive models, genome editing, genetic circuit engineering, and even de novo synthesis of plant genomes [1] [27]. However, a fundamental bottleneck constrains this vision: the recalcitrance of many plant species to genetic transformation and regeneration. Various plants have been genetically improved mostly through breeding and limited genetic engineering, yet they remain unable to meet ever-increasing needs for food, biomaterials, health, energy, and a sustainable environment [1]. A step-change addressing these challenges requires overcoming the biological barriers that limit our ability to genetically modify and regenerate diverse plant species, particularly those commercially important and minor crops that remain transformation-resistant [28] [29].

This technical guide examines the core biological principles, experimental methodologies, and emerging technologies that can address transformation and regeneration barriers across species, framed within the context of the Plant Biosystems Design Research Roadmap. The content is structured to provide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with both theoretical frameworks and practical tools to advance plant bioengineering capabilities across diverse species.

Core Biological Principles of Plant Regeneration

Regeneration Capacity Across Species

Plant regeneration is the process by which differentiated tissues/cells revert or convert their developmental fate and reconstruct new tissues or entire plants [30]. This capacity varies dramatically across species and tissue types, presenting a significant challenge for systematic biosystems design. Table 1 summarizes the key regeneration mechanisms observed across the plant kingdom.

Table 1: Plant Regeneration Mechanisms Across Species

| Regeneration Type | Description | Example Species | Key Regulators |

|---|---|---|---|

| De novo organogenesis | Regeneration of new structures not present in original explant | Arabidopsis, tobacco | WUS, WOX11, WOX12, cytokinins, auxins |

| Somatic embryogenesis | Formation of embryos from somatic cells | Carrot, cotton | LEC1, LEC2, AGL15, BBM |

| Callus-mediated regeneration | Formation of pluripotent cell mass before organogenesis | Most dicots | WIND1, LBD29, auxin |

| Direct regeneration without callus | Direct formation of organs from explants | Bryophytes, some monocots | Unknown species-specific factors |

| Developmental plasticity in non-vascular plants | High regenerative capacity without exogenous hormones | Marchantia polymorpha, Physcomitrella patens | Unknown conserved pathways |

Cellular Totipotency and Dedifferentiation

The fundamental principle underlying all plant regeneration is cellular totipotency - the ability of a single cell to regenerate into an entire organism [28]. This capability is enabled through dedifferentiation, where mature cells lose their specialized characteristics and reacquire stem cell-like properties [31] [30]. In vascular plants, this process typically involves the formation of callus - a mass of dedifferentiated cells that can be induced to form new organs under appropriate hormonal cues [31].

Recent research has revealed that callus formation does not represent a random disorganization of tissues but follows a developmental pathway that resembles root primordia formation, explaining why callus cells maintain developmental competence [30]. The molecular regulation of dedifferentiation involves transcription factors such as WIND1 in Arabidopsis, which promotes the initial step of cell fate transition [30].

Molecular Framework of Regeneration

Key Signaling Pathways

The molecular control of plant regeneration involves a complex interplay of hormone signaling, transcription factors, and epigenetic regulators. The core pathway for de novo shoot regeneration involves a hierarchical regulatory network with auxin and cytokinin as primary hormonal cues.

Diagram: Molecular Pathway of De Novo Shoot Regeneration

Epigenetic Regulation

Epigenetic mechanisms play a crucial role in enabling the cellular reprogramming necessary for regeneration. Key epigenetic processes include:

- DNA methylation: Global demethylation often precedes the acquisition of regenerative competence, as evidenced by enhanced embryogenesis when treated with DNA demethylating agents like 5-azacytidine [30].

- Histone modifications: Inhibition of histone H3K9 methylation by BIX-01294 promotes stress-induced microspore totipotency and enhances embryogenesis initiation [30].

- Chromatin remodeling: Differentiated cells typically show more nuclear condensation and heterochromatin, while cells acquiring regenerative competence exhibit chromatin decondensation with large nuclei and homogenous euchromatin [30].

The Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) has been identified as a key suppressor of dedifferentiation in mature somatic cells, maintaining cell fate commitment by repressing embryonic programs in adult tissues [30].

Technical Approaches to Transformation

Classification of Transformation Methods

Plant transformation technologies can be broadly categorized into direct gene transfer methods and bio-mediated transformation methods [28]. Table 2 provides a comparative analysis of major transformation approaches.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Plant Transformation Methods

| Method | Principle | Key Species | Efficiency Range | Major Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agrobacterium-mediated | Natural gene transfer from bacteria to plant cells | Dicots, some monocots | 0.1-90% | Simple, low cost, single-copy integration | Host range limitations, genotype-dependent |

| Pollen-tube pathway | DNA entry via pollen tube during fertilization | Cotton, soybean, melon | 0.5-2.5% | Bypasses tissue culture, simple | Limited to flowering species, low efficiency |

| Biolistic | Physical DNA delivery via microprojectiles | Cereals, woody species | 0.1-5% | Species-independent, organelle transformation | Complex integration patterns, equipment cost |

| Protoplast transformation | DNA uptake by plant cells without cell wall | Tobacco, Arabidopsis, lettuce | 1-20% | High efficiency, uniform delivery | Regeneration difficulties, technical complexity |

| Floral dip | Infiltration of flowering tissues with Agrobacterium | Arabidopsis, some Brassicaceae | 0.5-3% | Simple, no tissue culture | Limited species applicability |

| In planta meristem transformation | Direct transformation of shoot apical meristems | Cotton, soybean, peanut | 0.1-15% | Minimal tissue culture, genotype-independent | Technical challenge of meristem access |

In Planta Transformation Strategies

Recent advances in in planta transformation offer promising alternatives to conventional methods that require extensive tissue culture. These approaches are characterized by minimal or no tissue culture steps, making them particularly valuable for genotype-independent transformation [29]. The main in planta strategies can be classified based on their target tissues:

- Germline transformation: Targets ovule (female) or pollen (male) gametes before fertilization [29]

- Zygote transformation: Direct transformation of fertilized zygotes as progenitor stem cells [29]

- Meristem transformation: Targets shoot apical or adventitious meristems to exploit their regenerative capacity [29]

- Vegetative tissue transformation: Uses dedifferentiation of somatic tissues followed by direct regeneration [29]

Diagram: In Planta Transformation Workflow

Experimental Protocols for Enhanced Regeneration

Hormonal Optimization for Callus Induction and Organogenesis

A critical step in overcoming regeneration barriers is the optimization of hormone treatments to trigger cellular dedifferentiation and subsequent redifferentiation into organs.

Protocol: Systematic Optimization of Hormone Ratios

Explant preparation: Select appropriate explant material based on species:

- For dicots: leaf discs, hypocotyl segments, or root sections

- For monocots: immature embryos, basal meristem regions

- For woody species: nodal segments, shoot tips

Callus induction medium:

- Base: MS (Murashige and Skoog) or B5 medium with 3% sucrose and 0.8% agar

- Auxin: 2,4-D (0.5-3.0 mg/L) or NAA (0.1-2.0 mg/L)

- Cytokinin: Kinetin or BAP (0.1-1.0 mg/L) for synergistic effect

- Additives: Casein hydrolysate (0.5 g/L), myo-inositol (100 mg/L)

Shoot induction medium:

- High cytokinin:auxin ratio (typically 10:1 to 100:1)

- Cytokinins: BAP (1.0-5.0 mg/L) or Zeatin (0.5-3.0 mg/L)

- Auxins: Low concentration NAA (0.01-0.1 mg/L) or IAA (0.05-0.2 mg/L)

Root induction medium:

- High auxin:cytokinin ratio

- Auxins: IBA (0.5-2.0 mg/L) or NAA (0.1-1.0 mg/L)

- Optional additives: Activated charcoal (0.1-0.3%) for phenolic species

Molecular Enhancement of Regeneration Capacity

Genetic approaches can significantly enhance regeneration efficiency in recalcitrant species:

Protocol: Expression of Developmental Regulators

Identification of key regulators:

- Master regulators: WUSCHEL (WUS), BABY BOOM (BBM), WUSCHEL-RELATED HOMEOBOX (WOX) genes

- Fate transition promoters: WIND1, PLETHORA (PLT) genes

- Embryogenic regulators: LEAFY COTYLEDON (LEC1, LEC2)

Transient expression system:

- Utilize Agrobacterium or biolistic delivery of morphogenic genes

- Employ dexamethasone-inducible systems for precise temporal control

- Use CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) systems to enhance endogenous gene expression

Stable integration approaches:

- Incorporate regeneration-enhancing genes into transformation vectors

- Use excision systems (CRE-lox, FLP-FRT) to remove selectable markers and morphogenic genes after regeneration

- Employ tissue-specific or chemical-inducible promoters to control gene expression

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Transformation and Regeneration Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hormones and Growth Regulators | 2,4-D, NAA, IAA, IBA, BAP, Zeatin, TDZ | Direct cell fate transitions, organogenesis | Concentration optimization critical; species-specific responses |

| Morphogenic Regulators | WUS, BBM, WOX genes | Enhance regenerative competence | Often required for monocot transformation; use inducible systems |

| Epigenetic Modulators | 5-azacytidine, BIX-01294, Trichostatin A | Modify DNA methylation/histone acetylation | Can induce somaclonal variation; requires concentration optimization |

| Stress Inducers | Hydrogen peroxide, heat shock, heavy metals | Trigger cellular reprogramming | Mild stress often enhances competence; severe stress causes cell death |

| Signal Pathway Modulators | Auxin transport inhibitors (NPA, TIBA), cytokinin antagonists | Manipulate endogenous hormone pathways | Can overcome species-specific hormonal imbalances |

| Physical Treatment Tools | Ultrasound, electroporation, nanoparticle mediators | Enhance DNA delivery, membrane permeability | Particularly useful for in planta methods; species-dependent efficiency |

| Visualization and Selection | GFP, RFP, GUS, antibiotic/herbicide resistance genes | Transformant selection, process monitoring | Fluorescent proteins enable real-time tracking of regeneration |

Species-Specific Considerations and Applications

Overcoming Barriers in Major Crop Species

Different plant families present distinct challenges for transformation and regeneration. Table 4 summarizes key barriers and solutions for major crop categories.

Table 4: Species-Specific Transformation and Regeneration Challenges

| Plant Category | Key Barriers | Successful Strategies | Efficiency Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cereals (rice, maize, wheat) | Limited competence of explants, genotype dependence | Immature embryos as explants, morphogenic genes (WUS, BBM) | Rice: 5-90%, Maize: 5-40%, Wheat: 1-20% |