Plant Omics Data Standardization: Bridging Foundational Research to Clinical Translation

The rapid expansion of plant omics technologies generates vast, complex datasets, yet the lack of standardized data and metadata practices severely hinders data interoperability, reproducibility, and secondary use.

Plant Omics Data Standardization: Bridging Foundational Research to Clinical Translation

Abstract

The rapid expansion of plant omics technologies generates vast, complex datasets, yet the lack of standardized data and metadata practices severely hinders data interoperability, reproducibility, and secondary use. This article addresses the critical challenge of standardizing plant omics data by exploring the foundational principles of data interoperability, showcasing cutting-edge methodological applications like foundation models and multimodal integration, and providing practical troubleshooting strategies for experimental design and data heterogeneity. Targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we present a comparative analysis of existing frameworks and tools, emphasizing how robust standardization can accelerate the translation of plant-based discoveries into clinical and biomedical innovations.

The Why and What: Foundational Principles and Urgent Needs in Plant Omics Standardization

Inconsistent data standards represent a critical gap in plant omics research, creating significant barriers to data sharing, integration, and reproducibility. This technical support center addresses the specific challenges researchers face when working with plant multi-omics data, providing practical solutions to enhance data quality, interoperability, and ultimately, research progress.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Missing Data in Multi-Omics Integration

Problem: High percentages of missing data across different omics layers (e.g., transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) preventing effective data integration and analysis.

Background: Missing data is a fundamental challenge in multi-omics integration because all biomolecules are not measured in all samples. This occurs due to cost constraints, instrument sensitivity limitations, or other experimental factors [1]. In proteomics alone, 20-50% of potential peptide observations may be missing [1].

Step-by-Step Solution:

Classify Your Missing Data Mechanism:

- Missing Completely at Random (MCAR): Missingness does not depend on observed or unobserved variables

- Missing at Random (MAR): Missingness depends on observed variables but not unobserved data

- Missing Not at Random (MNAR): Missingness depends on the unobserved measurements themselves [1]

Select Appropriate Handling Methods Based on Classification:

- For MCAR/MAR: Use imputation methods (k-nearest neighbors, matrix factorization)

- For MNAR: Implement missing data algorithms that account for the missingness mechanism

- Consider recent AI and statistical learning approaches designed for partially observed samples [1]

Validate Your Approach:

- Compare multiple imputation methods

- Assess impact on downstream analysis

- Document all handling procedures thoroughly

Prevention Strategies:

- Standardize sample preparation protocols across omics types

- Implement quality control checkpoints throughout data generation

- Use standardized reference materials where available

Guide 2: Fixing Inconsistent Metadata Submission

Problem: Metadata (data about data) is incomplete, inconsistently formatted, or uses conflicting terminologies, making data discovery, integration, and reinterpretation difficult [2] [3].

Background: Metadata enhances data discovery, integration, and interpretation, enabling reproducibility, reusability, and secondary analysis. However, metadata sharing remains hindered by perceptual and technical barriers [2].

Step-by-Step Solution:

Adopt Minimum Information Standards:

- Implement MIAME (Minimum Information About a Microarray Experiment) for gene expression data [4]

- Use MIAPE (Minimum Information About a Proteomics Experiment) for proteomics studies [4]

- Apply MIxS (Minimum Information about any (x) Sequence) standards for genomic, metagenomic, and marker gene sequences [3]

Follow Structured Metadata Collection:

Utilize Controlled Vocabularies and Ontologies:

- Use Plant Ontology (PO) for plant structures and growth stages

- Implement Plant Trait Ontology (TO) for phenotypic characteristics

- Apply Gene Ontology (GO) for functional annotation

Validation Checklist:

- All required metadata fields completed

- Consistent formatting applied throughout

- Controlled vocabularies used where available

- Sample relationships clearly documented

- Experimental conditions fully described

Guide 3: Correcting Data Formatting Inconsistencies

Problem: Data from different sources or platforms use incompatible formats, structures, or naming conventions, preventing effective data integration and comparison.

Background: Data standardization transforms data from various sources into a consistent format, ensuring comparability and interoperability across different datasets and systems [5] [6].

Step-by-Step Solution:

Establish Standardization Rules:

- Define consistent naming conventions (e.g., snake_case for all identifiers)

- Specify value formatting (YYYY-MM-DD for dates, ISO codes for currencies)

- Determine unit conversions (standardize measurements to SI units)

- Implement identifier resolution and mapping [6]

Apply Standardization Techniques:

- Data Type Standardization: Ensure consistent data types (date, numeric, text)

- Textual Standardization: Apply case conversion, punctuation removal, whitespace trimming

- Numeric Standardization: Standardize units, precision, and measurement types [5]

Implement Automated Validation:

- Use schema enforcement at data entry points

- Apply validation rules during transformation processes

- Conduct regular quality assessment checks

Common Standardization Scenarios:

Table: Data Standardization Techniques for Plant Omics

| Data Type | Common Inconsistencies | Standardization Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Identifiers | Different database sources (TAIR, UniProt, NCBI) | Map to standardized nomenclature using official databases |

| Sample Dates | Various formats (DD/MM/YYYY, MM-DD-YY) | Convert to ISO 8601 (YYYY-MM-DD) |

| Concentration Units | Mixed units (μM, mM, ng/μL) | Standardize to molar concentrations (M) with scientific notation |

| Plant Genotypes | Different naming conventions | Use established stock center designations |

| Geographical Data | Various coordinate formats | Convert to decimal degrees with WGS84 datum |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the minimum metadata requirements for plant omics experiments?

Answer: Minimum metadata requirements ensure your data is findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable (FAIR). For plant omics, essential metadata includes [4] [3]:

- Project Information: Project name, description, objectives, and contributors

- Sample Details: Plant species, variety, genotype, tissue type, developmental stage, growth conditions

- Experimental Design: Replication structure, control types, experimental variables

- Technical Specifications: Instrument platform, protocols, parameters, data processing methods

- Data Acquisition: Sequencing type, read length, coverage depth, quality metrics

The Genomic Standards Consortium's MIxS (Minimum Information about any (x) Sequence) checklist provides specific standards for genomic, metagenomic, and marker gene sequences [3].

FAQ 2: How can we handle missing data in multi-omics studies without compromising statistical integrity?

Answer: The appropriate handling method depends on classifying your missing data mechanism [1]:

Table: Missing Data Handling Strategies

| Mechanism | Description | Recommended Methods |

|---|---|---|

| MCAR (Missing Completely at Random) | Missingness is unrelated to any variables | Complete case analysis, simple imputation, maximum likelihood |

| MAR (Missing at Random) | Missingness depends on observed data but not unobserved values | Multiple imputation, sophisticated imputation algorithms |

| MNAR (Missing Not at Random) | Missingness depends on the unobserved values themselves | Selection models, pattern mixture models, Bayesian approaches |

For multi-omics integration, recent AI and statistical learning methods specifically designed for partially observed samples can capture complex, non-linear interactions while handling missing data [1]. Always document your missing data handling approach thoroughly and assess its impact on downstream analyses.

FAQ 3: What are the consequences of not following data standards in collaborative plant omics research?

Answer: Inconsistent data standards create multiple negative consequences:

- Reduced Reproducibility: Inability to reproduce or verify experimental results

- Inefficient Resource Use: Significant time spent cleaning and reformatting data instead of analysis

- Limited Data Reuse: Inability to leverage existing datasets for new discoveries or meta-analyses

- Impaired Collaboration: Difficulties sharing data across research groups or institutions

- Regulatory Challenges: Complications in regulatory submissions for crop development or drug discovery [7] [8]

Following established standards ultimately accelerates research progress by making data more valuable and usable across the scientific community.

FAQ 4: How do we balance the need for standardized data with rapidly evolving omics technologies?

Answer: Balancing standardization with technological evolution requires a flexible, iterative approach [3]:

- Focus on Core Principles: Implement FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) as a foundation

- Adopt Modular Standards: Use standards that can evolve with technology while maintaining core metadata requirements

- Implement Version Control: Track standard versions and updates in your data documentation

- Participate in Community Efforts: Engage with standards organizations to help shape evolving specifications

This approach maintains data utility while accommodating methodological advances.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Plant Omics Research

| Reagent/Material | Function | Standardization Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | High-quality nucleic acid isolation for genomic analyses | Use kits with validated performance metrics; document lot numbers and protocols |

| RNA Preservation Solutions | Stabilize RNA for transcriptomic studies | Record stabilization time; use consistent storage conditions (-80°C) |

| Reference Standards | Quality control and cross-platform normalization | Implement certified reference materials; document source and usage |

| Internal Standards (Metabolomics) | Quantification in mass spectrometry-based metabolomics | Use stable isotope-labeled compounds; record concentrations and vendors |

| Protein Ladders | Molecular weight calibration in proteomics | Document manufacturer, catalog numbers, and lot information |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines | Data processing and analysis | Version control; parameter documentation; containerization for reproducibility |

Experimental Workflow for Standardized Plant Multi-Omics

This workflow emphasizes standardization at every stage, from initial experimental design through final data sharing, addressing the critical gap that inconsistent data standards create in plant omics research.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Metadata and CDE Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete metadata missing critical phenotypes [9] | Metadata not consolidated from primary sources; scattered information [9] [10] | Create standardized metadata templates (e.g., Google Sheet) with a data dictionary; collate information post-generation [10]. |

| Data cannot be pooled or compared across studies [11] [12] | Use of custom, non-standard variables instead of Common Data Elements (CDEs) [12] | Search NIH CDE Repository or domain-specific repositories for existing CDEs; reuse them directly in study design [11] [12]. |

| Public repository submissions are rejected or returned | Metadata does not follow repository-specific required formats or standards [10] [13] | Refine metadata to required standards (e.g., MIxS for genomics, CF for climate); standardize column data and include units [10] [14]. |

| Difficulties in multi-omics data integration [15] | Data from different omics technologies have different measurement units, scales, and formats [15] | Preprocess data: normalize, remove technical biases, convert to common scale/unit, and format into a unified samples-by-feature matrix [15]. |

| Secondary analysis of data is impossible [9] | Essential sample-level metadata exists only in publication text, not in structured repository fields [9] | Deposit all sample-level metadata in public repositories using structured fields, not just in manuscript text or supplements [9]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the core components of data sharing standards for omics data? Data sharing standards for omics data consist of four main components [4]:

- Experiment Description Standards: "Minimum information" guidelines (e.g., MIAME, MIAPE) that specify the details needed to interpret and reproduce an experiment [4].

- Data Exchange Standards: Standardized data formats and models (e.g., MAGE-ML) that enable communication between organizations and software tools [4].

- Terminology Standards: Ontologies and controlled vocabularies (e.g., MGED Ontology, NCI Thesaurus) that provide consistent terms to describe experiments and data [4] [11].

- Experiment Execution Standards: Guidelines for physical reference materials, data analysis, and quality metrics to ensure comparability of results [4].

Q2: What is the practical difference between metadata and a Common Data Element (CDE)?

- Metadata is a broad term for all contextual information that describes, explains, and makes it easier to retrieve and use a dataset. It is "data about data" [13]. For an omics sample, this includes everything from collection time and location to sequencing protocols and analysis software versions [10].

- A Common Data Element (CDE) is a specific, standardized type of metadata. A CDE rigidly defines a single variable by binding a precise question to a set of allowed responses and is designed for reuse across multiple studies to ensure consistency [11] [12]. For example, a CDE would not just define a variable as "Sex," but would specify the exact question text and permissible values like "Male," "Female," and "Unknown," often linked to ontology codes [12].

Q3: Our study involves a rare plant species. What should we do if we cannot find existing CDEs for our specific needs? If no suitable CDEs are available after checking general (e.g., NIH CDE Repository) and domain-specific sources, you can create new elements. It is critical to document every change or new element creation clearly in a data dictionary or codebook. To support interoperability, annotate your new elements with ontology codes (e.g., from the Gene Ontology) and consider sharing your contributions with relevant standards bodies to support future community use [12].

Q4: What are the most critical metadata fields to include for plant omics data to ensure reusability? Based on an audit of over 61,000 studies, the most critical metadata attributes are organism, tissue type, age, and sex (where applicable) [9]. For plants, strain or cultivar information is also essential [9]. These fields represent the principal axes of biological heterogeneity and are mandated by most minimum-information standards. Ensuring these are complete and machine-readable in a public repository, not just in the publication text, is vital for data reusability [9].

Q5: How can I ensure my integrated multi-omics resource will be useful to other researchers? Design your integrated resource from the perspective of the end-user, not the data curator [15]. Before and during development, create real use-case scenarios. Pretend you are an analyst trying to solve a specific biological problem with your resource. This process will help you identify what is missing, what is difficult to use, and what could be improved, leading to a more functional and widely adopted resource [15].

Quantitative Data on Metadata Completeness

Metadata Availability in Public Repositories (2025 Study)

A 2025 study systematically assessed the completeness of public metadata accompanying omics studies in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) [9].

| Metric | Value | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Phenotype Availability | 74.8% (average across 253 studies) | Over 25% of critical metadata are omitted, hindering reproducibility [9]. |

| Availability in Repositories vs. Publications | 62% (repositories) vs. 3.5% (publication text) | Public repositories contain significantly more metadata than publication text alone [9]. |

| Studies with Complete Metadata | 11.5% | Only a small minority of studies share all relevant phenotypes [9]. |

| Studies with Poor Metadata (<40%) | 37.9% | A large portion of studies share less than half of the crucial metadata [9]. |

| Human vs. Non-Human Studies | Non-human studies have 16.1% more metadata available | Studies with non-human samples are more likely to include complete metadata [9]. |

Key Elements of a Common Data Element (CDE)

| Component | Description | Example from the NIH CDE Repository [12] |

|---|---|---|

| Data Element Label | A standard name for the variable. | CMS Discharge Disposition |

| Question Text | The exact question or prompt shown to the user. | "What was the patient's CMS discharge status code?" |

| Definition | A precise explanation of the variable's meaning. | "The CMS code specifying the status of the patient after being discharged from the hospital." |

| Data Type | The format of the expected response. | Value List |

| Permissible Values (PVs) | The standardized set of allowed responses, their definitions, and links to ontology concepts. | Home (A person's permanent place of residence; NCIt Code C18002), Hospice, etc. |

Experimental Protocols for Standardization

Protocol 1: Submitting Omics Data to a Public Repository

This protocol outlines the steps for preparing and submitting omics data and metadata to a public repository like the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) or the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA), based on guidelines from NOAA and other sources [10].

- Plan and Collate Metadata: Before data generation, plan what metadata will be captured. Use a standardized template (e.g., a spreadsheet with a data dictionary) for consistent recording. Collate metadata from primary sources (e.g., lab notebooks) and associate it with sample IDs as soon as possible [10].

- Refine and Standardize: Check for errors and fill in missing metadata using standardized language for missing values. Standardize the data in each column to a consistent format as defined in your data dictionary. Ensure attribute names are well-defined and include units where applicable [10].

- Choose the Correct Repository: Identify the appropriate repository for your data type (e.g., NCBI for nucleotide sequences, specialized repositories for metabolomics). Consult resources like FAIRsharing.org for guidance [10] [13].

- Format for Submission: Format your metadata according to the repository's specific requirements and relevant community standards (e.g., the Genomics Standards Consortium's MIxS standards) [10].

- Submit Data: Submit the data and metadata by the repository's deadline, which is often before a paper is published or within one to two years of a project's end date [10].

Protocol 2: Applying Common Data Elements in a New Study

This protocol describes how to identify and apply CDEs when designing a new data collection effort, such as a plant phenotyping study or patient registry [12].

- Clarify Research Context: Define your research domain (e.g., plant biology, rare diseases), the specific disease or population, and the types of data you are collecting (e.g., clinical, phenotypic, omics). This will help target the right CDE repositories [12].

- Search for Existing CDEs: First, check for any regulatory or domain-specific CDE requirements. Second, search general repositories like the NIH CDE Repository. Use filters to narrow down results to your research area [12].

- Evaluate and Select CDEs: For each candidate CDE, check its definition, permissible values, and whether it is annotated with ontology codes. Prefer CDEs that are machine-readable and semantically aligned [12].

- Reuse or Adapt: If a CDE fully meets your needs, reuse it directly. If minor adaptations are necessary, document all modifications clearly in a data dictionary. Be aware that adaptations may reduce comparability with other datasets [12].

- Annotate and Document: Preserve or add ontology codes to CDEs to enable machine-readable alignment. Your final dataset will likely include a mix of reused CDEs and new, context-specific variables; your codebook should clearly distinguish between them [12].

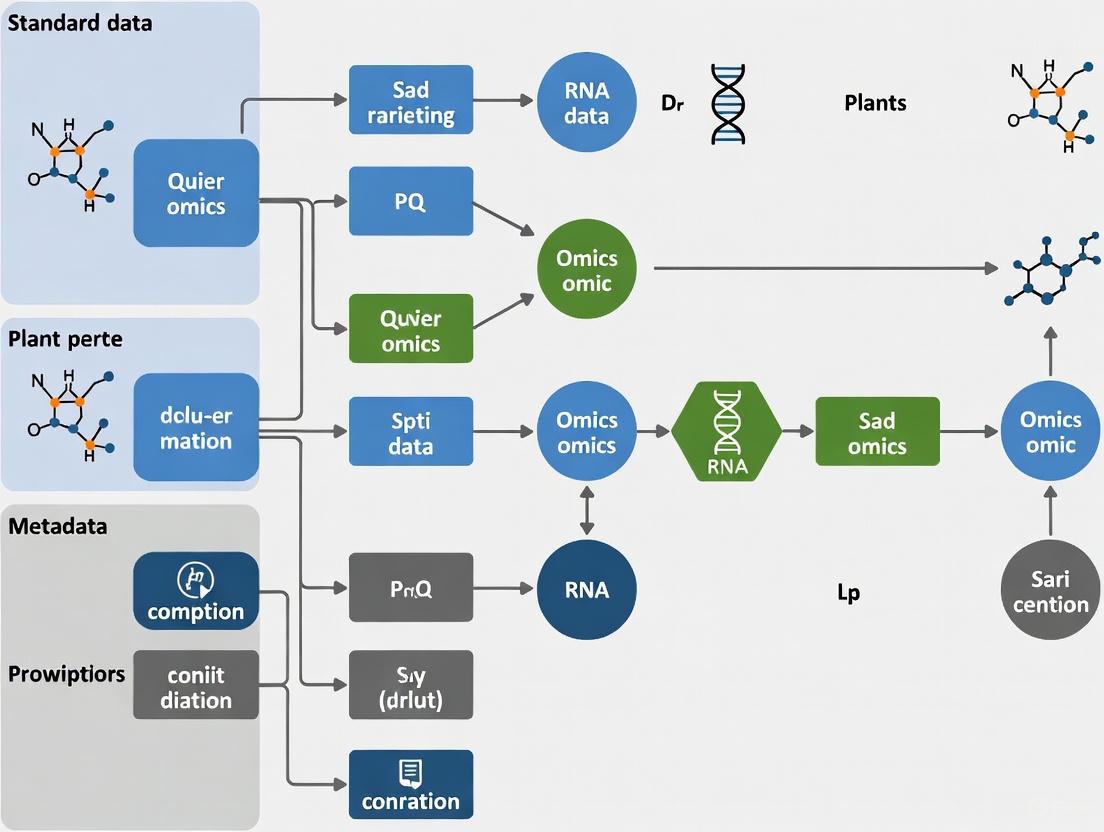

Diagrams for Standardization Workflows and Relationships

Data Standardization Components

Omics Data Sharing Workflow

Multi-omics Data Integration Process

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Common Data Elements (CDEs) | Standardized variables with defined questions and responses that ensure consistent data collection and enable cross-study comparisons [11] [12]. |

| Controlled Vocabularies & Ontologies | Predefined lists of terms (e.g., Gene Ontology, NCI Thesaurus) that standardize terminology, ensuring that all researchers describe the same concept with the same word, which is crucial for interoperability [11] [13]. |

| Minimum Information Standards (e.g., MIAME, MIAPE) | Guidelines that specify the minimum amount of meta-data required to unambiguously interpret and reproduce an experiment, often required by journals and public repositories [4]. |

| Metadata Templates & Data Dictionaries | Pre-formatted sheets (e.g., Google Sheets, Excel) with defined attribute columns and formats, used to capture metadata consistently from the start of a project [10]. |

| Sample Metadata | Contextual information about the primary sample, including collection time, location, type, and environmental conditions, which puts the omics data into context [10]. |

In contemporary plant research, omics technologies—including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—have revolutionized our capacity to understand biological systems at unprecedented scales. These approaches generate vast, complex datasets collectively termed "big data" due to their significant volume, diversity, and rapid accumulation [16]. However, the tremendous potential of this data remains constrained without robust frameworks for interoperability—the ability of different systems and organizations to exchange, interpret, and use data seamlessly. The interoperability imperative addresses critical scientific needs: enabling secondary data analysis that maximizes value from expensive-to-generate datasets, facilitating cross-study comparisons that reveal broader biological patterns, and supporting reproducible research through standardized methodologies and data descriptions. This technical support center provides essential guidance for researchers navigating the practical challenges of plant omics data interoperability, with troubleshooting guides and FAQs designed to address specific experimental hurdles within the broader context of standardizing plant omics data and metadata research.

Understanding Data Interoperability: Core Concepts

What is Interoperability in Plant Omics Research?

Interoperability in plant omics encompasses technical, semantic, and organizational dimensions that together enable meaningful data sharing and reuse. Technical interoperability ensures that data formats and structures are compatible across different computational platforms and analysis tools. Semantic interoperability guarantees that the meaning of data is preserved through standardized vocabularies, ontologies, and metadata schemas. Organizational interoperability establishes the policies, governance frameworks, and collaborative structures that support data exchange. Together, these dimensions create an ecosystem where data generated from diverse plant species, experimental conditions, and technological platforms can be integrated for secondary analysis, accelerating discoveries in plant biology, crop improvement, and drug development from plant-based compounds.

The FAIR Principles in Practice

The FAIR Guiding Principles—Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reusability—provide a foundational framework for interoperability. Plant Reactome, a comprehensive plant pathway knowledgebase, exemplifies FAIR implementation by providing curated reference pathways from rice and gene-orthology-based pathway projections to 129 additional species [17]. This resource enables users to analyze and visualize diverse omics data within the rich context of plant pathways while upholding global data standards. Implementing FAIR principles requires both technical solutions and researcher awareness, as even well-structured data fails to deliver value if researchers cannot locate, access, or interpret it effectively.

Technical Support Center: FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Data Generation and Experimental Design

FAQ: What are the key considerations for designing plant omics experiments to ensure future data sharing?

Answer: Thoughtful experimental design establishes the foundation for interoperable data. Key considerations include:

- Standards Selection: Identify and implement relevant community standards before data generation, including ontologies for plant structures (PO), plant traits (TO), and chemical entities (ChEBI).

- Metadata Documentation: Capture comprehensive experimental metadata using standardized templates, describing growth conditions, treatments, sampling procedures, and analytical protocols in sufficient detail to enable replication.

- Controls and Replicates: Include appropriate positive/negative controls and biological replicates that meet community standards for statistical power.

- Data Formats: Select non-proprietary, community-accepted file formats (e.g., mzML for metabolomics, BAM/SAM for genomics) that support long-term accessibility.

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Polyploid Complexity in Genomic Data

Challenge: Genome assembly and annotation of polyploid plants presents distinctive difficulties due to complex genome architectures with highly similar sequences, repetitive regions, and multiple homologous copies [18].

Solution Strategy:

- Sequencing Approach: Utilize highly accurate long-read sequencing technologies (e.g., PacBio HiFi) to distinguish between haplotypes [18].

- Specialized Assembly: For autopolyploids, employ specialized algorithms like ALLHiC, though note limitations for autopolyploid plants may necessitate experimental approaches such as sequencing large selfing populations [18].

- Epigenetic Considerations: Account for complex epigenetic regulation in polyploids, including DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNAs that significantly influence gene expression [18].

Data Processing and Analysis

FAQ: How can I ensure my processed plant omics data remains interoperable for secondary analysis?

Answer: Maintain interoperability during data processing through:

- Workflow Documentation: Use reproducible workflow systems (Nextflow, Snakemake) that capture all processing steps, parameters, and software versions.

- Version Control: Implement version control for both data and code using systems like Git, with persistent identifiers for specific analysis states.

- Parameter Transparency: Document all filtering thresholds, normalization methods, and statistical cutoffs with clear justifications.

- Standardized Outputs: Generate outputs in standard formats with sufficient metadata to trace back to raw data.

Table 1: Mass Spectrometry Platforms for Plant Metabolomics

| Platform/Technique | Resolution | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GC-MS [19] | Varies | Volatile compound analysis, primary metabolism | Quantitative, standardized spectral libraries | Requires derivatization, limited to volatile/thermostable compounds |

| LC-MS [19] | High to ultra-high | Secondary metabolites, non-volatile compounds | Broad compound coverage, minimal sample preparation | Complex data interpretation, limited standardized libraries |

| MALDI-MSI [19] | Spatial | Tissue-specific metabolite localization | Spatial distribution information, minimal sample preparation | Semi-quantitative challenges, complex sample preparation |

Troubleshooting Guide: Managing Multi-omics Data Integration

Challenge: Integrating diverse omics data types (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) presents significant computational and interpretive difficulties due to differing scales, structures, and biological meanings [20] [16].

Solution Strategy:

- Pathway-Centric Integration: Utilize established knowledgebases like Plant Reactome as a unifying framework, enabling projection of orthology-based pathways across species and providing context for multi-omics data visualization [17].

- Statistical Approaches: Implement multivariate methods (canonical correlation analysis, regularized canonical correlation analysis) specifically designed for heterogeneous data integration.

- Temporal Alignment: Carefully synchronize data collection timepoints across omics layers and employ temporal alignment algorithms when exact synchronization isn't feasible.

Data Sharing and Repository Submission

FAQ: What documentation is essential when submitting plant omics data to public repositories?

Answer: Comprehensive documentation enables secondary users to understand, evaluate, and properly reuse your data:

- Experimental Context: Detailed descriptions of biological materials, growth conditions, experimental treatments, and sampling procedures.

- Technical Metadata: Complete instrumentation details, platform specifications, and data generation protocols.

- Data Processing History: Transparent documentation of all transformations, from raw data to final results.

- Data Dictionary: Clear definitions for all variables, units of measurement, and coded values.

- Validation Information: Quality control metrics, normalization approaches, and any data quality issues.

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Incomplete Metadata

Challenge: Incomplete or inconsistent metadata severely limits data interoperability and reuse potential, particularly when integrating datasets from multiple sources or researchers.

Solution Strategy:

- Metadata Standards: Implement structured metadata collection using community-standardized schemas (ISA-Tab, MIAPPE) before experimentation begins.

- Cross-Reference: Utilize metadata repositories (MDRs) like Samply.MDR that structure data for technical processes while making syntax and semantics understandable for end users [21].

- Automated Extraction: Deploy tools that automatically extract technical metadata from instrument files to minimize manual entry errors.

- Validation Services: Use metadata validation tools provided by target repositories to identify missing or non-compliant elements before submission.

Experimental Protocols for Interoperable Plant Omics Research

Protocol: Mass Spectrometry-Based Metabolomics Workflow

This protocol outlines a standardized approach for plant metabolomics using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), generating data amenable to secondary analysis and cross-study comparison [19].

Materials and Reagents:

- Extraction solvent (e.g., methanol:water:chloroform, 2.5:1:1)

- Internal standards (e.g., stable isotope-labeled compounds)

- LC-MS grade solvents for mobile phase preparation

- Quality control samples (pooled quality control, process blanks)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- Harvest plant tissue using standardized procedures, immediately flash-freeze in liquid nitrogen, and store at -80°C.

- Precisely weigh frozen tissue (e.g., 100±5 mg) and homogenize with extraction solvent containing internal standards.

- Centrifuge at high speed (e.g., 15,000 × g, 15 min, 4°C) and transfer supernatant for analysis.

Instrumental Analysis:

- Utilize UHPLC system with reversed-phase column (e.g., C18, 1.7μm, 2.1×100mm).

- Implement gradient elution with water and acetonitrile, both containing 0.1% formic acid.

- Acquire data using high-resolution mass spectrometer (e.g., Q-TOF, Orbitrap) in both positive and negative ionization modes.

- Incorporate quality control samples throughout the sequence to monitor instrument performance.

Data Processing:

- Convert raw data to open formats (e.g., mzML, mzXML) using vendor converters or ProteoWizard.

- Perform peak detection, alignment, and integration using standardized software (e.g., XCMS, OpenMS).

- Annotate features using authentic standards when available, or putative identifications through database matching (mass, fragmentation spectrum).

- Export data matrix with feature intensities, sample metadata, and annotation information in standardized formats.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- Signal Drift: If quality control samples show systematic signal drift, apply quality control-based correction algorithms.

- Feature Misalignment: Adjust alignment parameters or employ retention time correction when observing poor peak alignment across samples.

- Low Annotation Rates: Supplement database searches with in-silico fragmentation prediction and apply level-based annotation confidence reporting.

Protocol: Genome Assembly for Complex Plant Genomes

This protocol provides guidance for generating high-quality genome assemblies for polyploid or highly heterozygous plant species, addressing particular challenges in complex plant genomes [22] [18].

Materials and Reagents:

- High molecular weight DNA extraction kit

- Library preparation reagents for long-read sequencing (PacBio, Nanopore)

- Hi-C library preparation kit (if pursuing chromosome-scale assembly)

- Quality assessment tools (e.g., Qubit, Nanodrop, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis)

Procedure:

- Sequencing Strategy Selection:

- For polyploid species, prioritize long-read sequencing technologies (PacBio HiFi, Oxford Nanopore) to resolve repetitive regions and distinguish haplotypes [22].

- Supplement with Hi-C or Omni-C data for chromosome-scale scaffolding.

- Consider complementary short-read data for polishing, though note HiFi reads may reduce this necessity.

Genome Assembly:

- Employ assemblers designed for complex genomes (e.g., Hifiasm, Canu, NECAT) based on data type and genome characteristics.

- For polyploids, utilize specialized tools (e.g., ALLHiC) for haplotype-phased assembly, noting limitations with autopolyploids [18].

- Perform iterative polishing using high-accuracy sequences to correct errors.

Quality Assessment and Annotation:

- Evaluate assembly completeness using BUSCO with plant-specific lineage datasets.

- Annotate repeats using structured approaches (e.g., EDTA pipeline) before gene prediction.

- Predict protein-coding genes using evidence-based and ab initio approaches, integrating transcriptomic data when available.

- Submit final assembly to public repositories (NCBI, EBI) with complete metadata.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- High Heterozygosity: If assembly exhibits excessive fragmentation due to high heterozygosity, consider specialized assemblers or alternate strategies like diploid-aware assembly.

- Repeat Resolution: If repetitive regions remain poorly assembled, target additional sequencing coverage specifically to problematic regions or employ linked-read technologies.

- Annotation Challenges: For difficult-to-annotate genomes, implement iterative annotation approaches and utilize orthogonal evidence (transcriptomes, homologous proteins).

Visualization: Workflows and Data Relationships

Plant Omics Data Interoperability Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete pathway from experimental design to data sharing, highlighting critical decision points that impact interoperability:

Multi-Omics Data Integration Framework

This diagram illustrates the conceptual framework for integrating diverse omics data types, highlighting both technical and biological integration points:

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Plant Omics Research

| Reagent/Tool | Category | Primary Function | Interoperability Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PacBio HiFi Reads [22] | Sequencing Technology | Generate highly accurate long reads | Enables haplotype resolution in polyploids; produces data compatible with multiple assembly tools |

| Plant Reactome [17] | Knowledgebase | Pathway analysis and data visualization | Provides FAIR-compliant data; enables cross-species comparisons through orthology projections |

| HL7 FHIR Standards [21] | Data Standard | Clinical and observational data exchange | Emerging standard for plant phenotyping data; supports semantic interoperability |

| Samply.MDR [21] | Metadata Repository | Metadata management and harmonization | ISO/IEC 11179-based; handles hierarchical data structures across multiple sources |

| mzML Format [19] | Data Format | Mass spectrometry data storage | Open, standardized format for metabolomics data; supported by multiple analysis platforms |

| BUSCO [22] | Quality Assessment | Genome assembly completeness evaluation | Provides standardized metrics for comparing assembly quality across different species |

The interoperability of plant omics data represents both a technical challenge and a scientific imperative. As the volume and complexity of plant science data continue to grow, establishing robust frameworks for data sharing and secondary analysis becomes increasingly critical for advancing fundamental knowledge and applied outcomes in agriculture, conservation, and drug development. The guidance provided in this technical support center addresses immediate practical concerns while situating these solutions within the broader context of standardization in plant omics research. By implementing these protocols, troubleshooting strategies, and interoperability-focused practices, researchers contribute to a collaborative ecosystem where data transcends individual studies to accelerate collective understanding of plant biology. The future of plant omics research depends not only on generating data but on building the connections—technical, semantic, and collaborative—that transform isolated findings into integrated knowledge.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Genomic Data Standards

1. What is the main goal of the Genomic Standards Consortium (GSC)? The GSC is an open-membership working body formed in 2005. Its primary aim is to make genomic data discoverable by enabling genomic data integration, discovery, and comparison through international community-driven standards [23].

2. What is IMMSA and who does it represent? The International Microbiome and Multi'Omics Standards Alliance (IMMSA) is an open consortium of microbiome-focused researchers from industry, academia, and government. Its members are representative experts for all major microbiological ecosystems (e.g., human/animal, built, and environmental) and from various scientific disciplines including microbiology, bioinformatics, genomics, metagenomics, proteomics, metabolomics, transcriptomics, epidemiology, and statistics [24].

3. What are the MIxS standards?

The Minimum Information about any (x) Sequence (MIxS) standards are a set of standardized checklists for reporting contextual metadata associated with genomics studies. Developed by the GSC, they provide a unifying resource for describing the sample and sequencing information, facilitating data comparison and reuse [25] [26]. The checklists are tailored to specific environments, such as MIMARKS for marker sequences, MIMS for metagenomes, and environment-specific packages for soil, water, and host-associated samples [26].

4. Why is metadata so critical for data reuse? Missing, partial, or incorrect metadata can lead to significant repercussions and faulty conclusions about taxonomy or genetic function [25]. Standardized metadata ensures that data is Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable (FAIR). It allows other researchers to understand the experimental context, which is vital for reproducing results and conducting new, integrated analyses [25].

5. What are common social challenges to data sharing and reuse? A key social challenge is incentivizing researchers to submit the complete breadth of metadata needed to replicate an analysis [25]. This includes attitudes and behaviors around data sharing and restricted usage, issues which can disproportionately impact early career researchers [25].

Troubleshooting Guides for Data Reproducibility

Problem: Inconsistent Results When Reusing Public Genomic Data

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Metadata | Incomplete or missing sample context [25]. | Use MIxS checklists during data submission [26]. Manually curate metadata from publications if necessary [25]. |

| Wet-Lab Methods | Laboratory methods/kits introduce bias (e.g., in taxonomic profiles) [25]. | Document & report DNA extraction & sequencing kits used. Use reference materials (e.g., from NIST) to benchmark performance [27]. |

| Data Availability | Data is in archives, but key files or access details are missing [25]. | Verify data accessions in publication. Check supplementary files for processed data. Contact corresponding author. |

| Technical Reproducibility | Unable to run the same computational pipelines. | Use containerized software (e.g., Docker, Singularity). Share analysis code in public repositories (e.g., GitHub). |

Problem: Low DNA Yield or Quality During Plant Omics Sampling

This guide adapts general principles from established molecular biology protocols to the context of plant genomics [28].

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low DNA Yield | Tissue pieces too large, leading to nuclease degradation [28]. | Cut tissue into the smallest possible pieces or grind with liquid nitrogen [28]. |

| DNA Degradation | High nuclease content in some plant tissues; improper sample storage [28]. | Flash-freeze samples in liquid nitrogen; store at -80°C; use stabilizing reagents [28]. |

| Protein Contamination | Incomplete digestion of the sample [28]. | Extend Proteinase K digestion time; ensure tissue is fully dissolved [28]. |

| RNA Contamination | Too much input material inhibiting RNase A [28]. | Do not exceed recommended input amount; extend lysis time [28]. |

Standardized Experimental Protocol: Ensuring Reusable Plant Omics Data

This protocol outlines a workflow for generating plant omics data that adheres to the standards promoted by IMMSA and the GSC, ensuring reproducibility and reusability.

Objective: To extract high-quality genomic DNA from plant tissue and prepare it for sequencing, with complete metadata documentation for public repository submission.

Materials:

- Plant tissue sample (e.g., leaf)

- Liquid Nitrogen and Mortar & Pestle

- Monarch Spin gDNA Extraction Kit (or equivalent) [28]

- Proteinase K and RNase A [28]

- MIxS Plant-Associated (MIxS - Plant-associated) checklist [26]

Methodology:

- Sample Collection & Stabilization:

- Immediately flash-freeze the collected plant tissue in liquid nitrogen.

- Store at -80°C if not processing immediately to prevent nuclease degradation [28].

- Tissue Disruption:

- Grind frozen tissue to a fine powder under liquid nitrogen using a mortar and pestle. Note: Keeping tissue frozen during grinding is critical to prevent DNA degradation [28].

- Genomic DNA Extraction & Purification:

- Follow a commercial kit's protocol (e.g., Monarch Spin gDNA Extraction Kit). Key considerations:

- Use the recommended mass of powdered tissue to avoid column overloading or incomplete lysis [28].

- Add Proteinase K and RNase A to the sample and mix well before adding the Cell Lysis Buffer [28].

- For fibrous tissues, centrifuge the lysate to remove indigestible fibers before loading onto the spin column [28].

- Elute DNA in the provided elution buffer.

- Follow a commercial kit's protocol (e.g., Monarch Spin gDNA Extraction Kit). Key considerations:

- Quality Control:

- Quantify DNA using a fluorometer and assess purity via spectrophotometry (A260/A280 and A260/A230 ratios).

- Check DNA integrity by agarose gel electrophoresis.

- Metadata Collection - The Critical Step for Reusability:

- Concurrently, populate the relevant MIxS Plant-Associated checklist [26]. Essential fields include:

- Investigation type: metagenome, genome, etc.

- Project name: Your specific project identifier.

- Latitude and Longitude: Geographic coordinates of sample collection.

- Collection date: When the sample was taken.

- Sample type (e.g., leaf, root, rhizosphere).

- Plant growth conditions: e.g., greenhouse, field, growth chamber.

- Environmental medium: e.g., soil, air, plant-associated.

- DNA extraction method: Document the kit and any protocol modifications.

- Sequencing platform and method: e.g., Illumina NovaSeq, PacBio HiFi.

- Concurrently, populate the relevant MIxS Plant-Associated checklist [26]. Essential fields include:

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow and logical relationships for creating reusable plant omics data, integrating both laboratory and computational steps with community standards.

Workflow for Reusable Plant Omics Data

Research Reagent Solutions for Standardized Omics

The following table lists key materials and resources essential for generating standardized, reproducible omics data.

| Resource / Reagent | Function & Importance in Standardization |

|---|---|

| MIxS Checklists [26] | Provides the standardized framework for reporting metadata, ensuring data is Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable (FAIR). |

| NIST Reference Materials (e.g., RM 8376) [27] | Benchmarked genomic DNA from multiple organisms. Used to assess performance of metagenomic sequencing workflows, enabling cross-lab comparability. |

| Monarch Kits / Equivalent [28] | Commercial DNA extraction kits with standardized, validated protocols that help reduce technical variability in sample preparation. |

| INSCD Repositories (GenBank, ENA, DDBJ) [25] [29] | The mandatory, archival public databases for nucleotide sequence data. Submission with complete MIxS metadata is required by most journals. |

Building the Framework: Methodologies, Tools, and Applications for Standardized Omics

What are the primary functions of the BioLLM and CZ CELLxGENE platforms?

BioLLM and CZ CELLxGENE serve as complementary computational ecosystems for managing and analyzing single-cell omics data. BioLLM functions as a standardized framework that provides a unified interface for integrating diverse single-cell foundation models (scFMs), enabling researchers to seamlessly switch between models like scGPT, Geneformer, and scFoundation for consistent benchmarking and analysis [30]. In contrast, CZ CELLxGENE is a comprehensive suite of tools that helps scientists find, download, explore, analyze, annotate, and publish single-cell datasets [31]. Its Discover portal provides access to a massive, standardized corpus of over 33 million unique cells from hundreds of datasets, while its Census component offers efficient low-latency API access to this data for computational research [32] [33].

How do these platforms support the standardization of plant omics data specifically?

While the platforms host and support data from multiple species, they provide critical infrastructure that can be leveraged for plant omics research. The CZ CELLxGENE Census includes data from multiple organisms and provides standardized cell metadata with harmonized labels, which is a fundamental requirement for cross-species comparative analyses [32]. For plant-specific research, scPlantFormer has been developed as a lightweight foundation model pretrained on 1 million Arabidopsis thaliana cells, demonstrating exceptional capabilities in cross-species data integration and cell-type annotation [34]. When using these platforms for plant research, ensure you select the appropriate organism-specific data, as some features like cross-species queries may be limited due to differing gene annotations [32].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Data Access and Query Performance

Why are my data queries in CZ CELLxGENE Census running slowly?

Query performance in the Census is primarily limited by internet bandwidth and client location. For optimal performance:

- Utilize a computer connected to high-speed internet, preferably with an ethernet connection rather than WiFi [32]

- Deploy computing resources located on the west coast of the US when possible [32]

- For the best performance, use EC2 AWS instances in the

us-west-2region where the data is hosted [32]

Can I query both human and mouse data in a single Census query?

No, the Census does not support querying both human and mouse data in a single query. This limitation exists because data from these organisms use different organism-specific gene annotations [32]. You must perform separate queries for each organism.

How can I access the original author-contributed normalized expression values or embeddings?

The Census does not contain normalized counts or embeddings because the original values are not harmonized across datasets and are therefore numerically incompatible [32]. If you need this data, access web downloads directly from the CZ CELLxGENE Discover Datasets feature instead of using the Census API [32].

Installation and Technical Issues

I encountered a weird error when trying to pip install cellxgene. What should I do?

This may occur due to bugs in the installation process. The developers recommend:

- Creating a new Github issue and explaining what you did [35]

- Including all error messages you saw [35]

- Running

pip freezeand including the full output alongside your issue [35]

Why do I get an ArraySchema error when opening the Census?

This error typically occurs when using an old version of the Census API with a new Census data build. To resolve this:

- Update your Python or R Census package to the latest version [32]

- If the error persists, file a github issue for further support [32]

How do I resolve installation or import errors for cellxgene_census on Databricks?

When installing on Databricks, avoid using %sh pip install cellxgene_census as this doesn't restart the Python process after installation. Instead, use:

%pip install -U cellxgene-censusorpip install -U cellxgene-census[32]

These "magic" commands properly restart the Python process and ensure the package is installed on all nodes of a multi-node cluster [32].

How do I connect to the Census from behind a proxy?

TileDB doesn't use typical proxy environment variables. Configure your connection explicitly using:

Platform Integration Workflow for Plant Omics Analysis

Troubleshooting Decision Tree for Platform Issues

Foundation models are transforming single-cell omics analysis, offering powerful new paradigms for integrating complex biological data across species. In plant sciences, where data standardization is a significant challenge, models like scGPT and scPlantFormer provide frameworks for cross-study and cross-species analysis that can overcome batch effects and annotation inconsistencies. This technical support center addresses the specific implementation challenges researchers face when deploying these advanced AI tools, with a focus on standardizing plant omics data and metadata practices to ensure reproducible, FAIR-compliant research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the fundamental differences between scGPT and scPlantFormer, and how do I choose between them for my plant single-cell project?

A1: scGPT is a comprehensive foundation model pretrained on over 33 million cells across multiple species, excelling in general single-cell multi-omics tasks including perturbation modeling and gene regulatory network inference [36]. In contrast, scPlantFormer is a specialized lightweight model specifically designed for plant single-cell omics, pretrained on one million Arabidopsis thaliana scRNA-seq data points [37]. Choose scGPT for multi-omics integration or cross-species analysis beyond plants, while scPlantFormer offers optimized performance for plant-specific applications with significantly lower computational requirements.

Table: Comparison of scGPT and scPlantFormer Foundation Models

| Feature | scGPT | scPlantFormer |

|---|---|---|

| Training Data Scale | 33+ million cells [36] | 1 million Arabidopsis cells [37] |

| Primary Application Scope | General single-cell multi-omics | Plant-specific single-cell transcriptomics |

| Computational Requirements | High (requires GPU, flash-attention) [38] | Lightweight (laptop-compatible) [37] |

| Key Innovation | Generative AI for multi-omics integration [36] | CellMAE pretraining strategy for efficiency [37] |

| Cross-Species Accuracy | High for mammalian systems [36] | 92% for plant species [37] |

Q2: How do I properly prepare single-cell data from plant tissues to ensure compatibility with these foundation models?

A2: Plant single-cell analysis presents unique challenges, primarily the decision between single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq). scRNA-seq requires enzymatic digestion to create protoplasts, which can affect transcriptional states, while snRNA-seq can be performed on fresh, frozen, or fixed material but typically yields lower UMI counts and gene detection [39]. For foundation model compatibility, ensure your data includes:

- High-quality cell suspensions: Visual assessment of protoplast generation or nucleus release across all desired cell types

- Appropriate controls: Cell-type-specific markers for protocol validation

- Minimum quality thresholds: >90% viability, minimal debris and aggregation [40]

- Standardized metadata: Follow FAIR principles using tools like Swate with plant-specific templates (MIAPPE standards) [41]

Q3: What computational infrastructure is required to implement scGPT and scPlantFormer, and how can I optimize for limited resources?

A3: scGPT requires Python ≥3.7.13, PyTorch, and benefits significantly from GPU acceleration with specific CUDA compatibility (recommended CUDA 11.7 with flash-attention<1.0.5) [38]. For limited resources, scPlantFormer's patch-based architecture and CellMAE pretraining strategy dramatically reduce computational requirements, enabling operation on standard laptops [37]. Cloud-based solutions and the availability of pretrained model zoos for scGPT reduce local computational burdens.

Table: Computational Requirements and Optimization Strategies

| Requirement | scGPT | scPlantFormer |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum Python Version | 3.7.13 [38] | 3.7+ [37] |

| GPU Acceleration | Required for optimal performance [38] | Optional (laptop-compatible) [37] |

| Memory Requirements | High (for large datasets) [36] | Optimized via patching strategy [37] |

| Pretrained Models | Available in model zoo [38] | Built-in for plant data [37] |

| Installation Command | pip install scgpt "flash-attn<1.0.5" [38] |

Custom installation from source [37] |

Q4: How do foundation models address the critical challenge of batch effects in cross-species integration of plant omics data?

A4: Both scGPT and scPlantFormer employ advanced strategies to mitigate batch effects. scGPT uses transfer learning frameworks that enhance robustness to technical variation across protocols and species [36]. scPlantFormer specifically addresses plant data challenges through its novel pretraining approach that captures biological signals while minimizing technical artifacts, achieving high cross-dataset annotation accuracy even with limited labeled data [37]. For optimal results, always:

- Process each sample individually before integration

- Perform quality control on each dataset separately

- Document filtering thresholds for reproducibility

- Use biological replicates (not technical replicates) for statistical validation [39]

Q5: What experimental validation is required to confirm cross-species cell type predictions generated by these foundation models?

A5: Foundation model predictions require rigorous experimental validation, particularly for novel cross-species cell type identifications. Recommended validation approaches include:

- Reporter lines for visual confirmation of predicted cell types

- Spatial transcriptomics to verify tissue localization patterns

- In situ hybridization for marker gene expression validation

- Differential expression analysis of pseudobulked samples to confirm cell-type-specific markers [39]

Always include proper biological replicates in your experimental design to avoid sacrificial pseudoreplication, which can dramatically increase false positive rates in differential expression analysis [40].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Cross-Species Annotation Accuracy

Symptoms: Low confidence scores for cell type predictions, inconsistent annotation across similar cell types, failure to identify conserved cell types.

Solution:

- Data Quality Assessment: Verify that your query dataset meets quality thresholds (median genes per cell, mitochondrial read percentage, UMI counts) [42]

- Reference Dataset Compatibility: Ensure reference and query datasets share biologically relevant cell types

- Batch Effect Correction: Apply appropriate batch correction methods before foundation model application

- scPlantFormer Workflow Implementation: Utilize the specialized workflows in scPlantFormer designed specifically for cross-dataset cell-type annotation [37]

Issue 2: Computational Resource Limitations

Symptoms: Memory errors during training, extremely slow inference times, inability to load pretrained models.

Solution:

- scGPT Optimization:

- Utilize flash-attention optional dependency [38]

- Employ the provided model zoo with pretrained weights

- Use reference mapping for large datasets (FAISS integration)

scPlantFormer Advantages:

- Leverage the lightweight architecture designed for efficiency

- Implement the CellMAE pretraining strategy

- Utilize patch-based processing for reduced memory footprint [37]

General Optimization:

- Start with subset of data for protocol development

- Use cloud resources for large-scale analysis

- Implement data chunking for memory-intensive operations

Issue 3: Inconsistent Results Across Biological Replicates

Symptoms: Different cell type proportions across replicates, variable gene expression patterns, statistical significance issues.

Solution:

- Proper Replicate Design:

- Ensure true biological replicates (independent growth, harvesting, processing)

- Avoid treating technical replicates as biological replicates [39]

Statistical Validation:

- Implement pseudobulking approaches to account for between-sample variation

- Use appropriate statistical tests that consider biological replicate structure

- Calculate correlation coefficients between replicate expression profiles

Foundation Model Tuning:

- Utilize scPlantFormer's few-shot learning capabilities for limited data

- Apply transfer learning with scGPT to adapt to specific experimental conditions

- Validate with cluster-specific differentially expressed genes

Issue 4: Integration with Existing Single-Cell Analysis Pipelines

Symptoms: Format incompatibility, inability to export results to standard tools, workflow disruption.

Solution:

- Data Format Compatibility:

- Ensure data in standard formats (H5AD, CSV, Seurat objects)

- Preprocess with tools like Cell Ranger for 10x Genomics data [42]

- Use quality control metrics compatible with foundation model requirements

Workflow Integration:

- Utilize scGPT's compatibility with Scanpy/Seurat ecosystems [38]

- Implement scPlantFormer within established plant single-cell workflows

- Export results for visualization in standard tools (Loupe Browser, UCSC Cell Browser)

Metadata Management:

- Annotate with FAIR-compliant metadata using Swate templates [41]

- Document all preprocessing and analysis steps for reproducibility

- Use standardized ontologies for cell type annotations

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Foundation Model Implementation in Plant Single-Cell Omics

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Single-cell RNA-seq kits (10x Genomics 3' Gene Expression) | Transcriptome profiling | Choose between scRNA-seq (protoplasts) and snRNA-seq (nuclei) based on biological question [39] |

| Enzyme solutions for protoplasting | Cell wall digestion for scRNA-seq | Optimize with L-cysteine, sorbitol, or L-arginine for specific species [39] |

| Nuclei isolation buffers | Nuclear extraction for snRNA-seq | Compatible with fresh, frozen, or fixed material [39] |

| Cell viability stains | Quality assessment | Critical for evaluating protoplast/nuclei preparations [40] |

| FAIRdom SEEK/pISA-tree | Metadata management | Plant-specific FAIR data capture systems [43] |

| Swate annotation templates | Standardized metadata | ISA-based templates with plant ontology terms [41] |

| Pretrained model weights | Foundation model initialization | Available for both scGPT and scPlantFormer [38] [37] |

Advanced Workflow: Cross-Species Integration Protocol

Objective: Identify conserved cell types across plant species using scPlantFormer foundation model.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Data Collection and Curation

- Gather scRNA-seq datasets from multiple plant species

- Apply stringent quality control: UMI counts, gene detection, mitochondrial percentage

- Annotate with standardized metadata using Swate with MIAPPE templates [41]

Preprocessing for Foundation Model Compatibility

- Identify 8,000 highly variable genes (HVGs) following scPlantFormer protocol [37]

- Partition gene expression vectors into equally sized sub-vectors

- Apply 75% random masking using CellMAE strategy

Model Application and Cross-Species Mapping

- Generate cell embeddings using scPlantFormer encoder

- Perform reference-based annotation with limited labeled data (1% labels)

- Identify conserved cell types through shared embedding spaces

Validation and Biological Interpretation

- Validate predictions with marker gene expression

- Perform differential expression analysis on pseudobulked samples

- Confirm findings with spatial transcriptomics or in situ hybridization [39]

This technical support framework provides plant researchers with practical solutions for implementing cutting-edge foundation models while maintaining rigorous standards for data quality, metadata annotation, and experimental validation—essential components for advancing cross-species integration in plant omics research.

Modern biology has moved beyond single-data-type analyses. Multi-omics integration combines data from various molecular levels—such as the genome, transcriptome, epigenome, and proteome—to create a comprehensive understanding of biological systems [44]. In plant research, this approach is particularly powerful for connecting genotypic information to complex phenotypic traits like flowering time and stress resilience [45] [46].

The core challenge lies in the sheer complexity and heterogeneity of the data. Each omics layer has unique data scales, noise profiles, and measurement sensitivities, making integration non-trivial [47]. For instance, actively transcribed genes should theoretically have greater chromatin accessibility, but this correlation does not always hold true in practice. Similarly, abundant proteins may not always correlate with high gene expression levels due to post-transcriptional regulation [47]. Overcoming these hurdles requires sophisticated computational tools and standardized experimental protocols, especially in the context of plant systems with their diverse metabolites and poorly annotated genomes [44].

Key FAQs on Multi-Omics Data Generation

Q1: What are the primary types of multi-omics integration strategies?

Integration strategies are broadly classified based on how the data is sourced and combined. The table below outlines the main computational approaches.

Table: Multi-Omics Integration Strategies and Tools

| Integration Type | Data Source | Description | Example Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Matched (Vertical) [47] | Different omics from the same cell | Uses the cell itself as an anchor to integrate modalities. Ideal for concurrent RNA & protein or RNA & ATAC-seq data. | Seurat v4, MOFA+, totalVI, scMVAE |

| Unmatched (Diagonal) [47] | Different omics from different cells | Projects cells into a co-embedded space to find commonality, as there is no direct cellular anchor. | GLUE, Pamona, UnionCom, Seurat v3 |

| Mosaic Integration [47] | Various omic combinations across samples | Integrates datasets where each sample has measured different, but overlapping, combinations of omics. | Cobolt, MultiVI, StabMap |

| Spatial Integration [48] [47] | Omics data with spatial coordinates | Leverages spatial location as an anchor to co-profile or integrate multiple omics layers within a tissue context. | Spatial ATAC-RNA-seq, Spatial CUT&Tag-RNA-seq, ArchR |

Q2: How is spatial multi-omics data generated, and what are its advantages?

Spatial multi-omics technologies allow for the genome-wide, joint profiling of multiple molecular layers, such as the epigenome and transcriptome, on the same tissue section at near-single-cell resolution [48].

The workflow involves fixing a tissue section and simultaneously processing it for two different omics reads. For example, in Spatial ATAC–RNA-seq, the tissue is treated with a Tn5 transposition complex to tag accessible genomic DNA, while a biotinylated adaptor binds mRNA to initiate reverse transcription [48]. A microfluidic chip with a grid of channels is then used to introduce spatial barcodes onto the tissue, tagging each "pixel" with a unique molecular identifier. After processing, the libraries for gDNA and cDNA are constructed and sequenced separately [48].

This co-profiling preserves the tissue architecture, enabling researchers to directly link epigenetic mechanisms to transcriptional phenotypes within the native tissue context and uncover spatial epigenetic priming and gene regulation [48].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Q3: Our NGS library yields are consistently low. What are the main causes and solutions?

Low library yield is a common bottleneck in preparing omics data. The following table outlines frequent issues and their corrective actions.

Table: Troubleshooting Low NGS Library Yield

| Root Cause | Mechanism of Failure | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Input Quality / Contaminants [49] | Residual salts, phenol, or polysaccharides inhibit enzymatic reactions (ligation, polymerase). | Re-purify input sample; use fluorometric quantification (Qubit); ensure high purity ratios (260/230 > 1.8). |

| Fragmentation & Ligation Failures [49] | Over- or under-shearing creates suboptimal fragment sizes; poor ligase performance or incorrect adapter ratios. | Optimize fragmentation parameters; titrate adapter-to-insert molar ratio; ensure fresh ligase and buffer. |

| Amplification Problems [49] | Too many PCR cycles introduces bias and duplicates; enzyme inhibitors remain from prior steps. | Reduce the number of PCR cycles; use master mixes to reduce pipetting errors and improve consistency. |

| Purification & Size Selection Loss [49] | Incorrect bead-to-sample ratio or over-drying of beads leads to inefficient recovery of target fragments. | Precisely follow cleanup protocols; avoid over-drying magnetic beads. |

Q4: When integrating transcriptomic and epigenomic data, the correlations are weak. Is this normal, and how can it be resolved?

Yes, this is a common and expected challenge. Machine learning models built for traits like flowering time in Arabidopsis using genomic (G), transcriptomic (T), and methylomic (M) data have shown that models from different omics layers identify distinct sets of important genes [45]. The feature importance scores between different omics types show weak or no correlation, indicating they capture complementary biological signals [45].

To address this:

- Do not expect perfect linear correlations. The relationship between epigenomic state and transcript abundance is complex and non-linear.

- Use integrated machine learning models. Models that combine G, T, and M data simultaneously have been shown to perform best and can reveal known and novel gene interactions [45].

- Leverage specialized computational tools designed for unmatched data integration, such as manifold alignment or variational autoencoders, which can find commonality between datasets without relying on simple correlation [47].

Q5: What specific challenges exist for multi-omics integration in plant systems?

Plants present unique obstacles that require special consideration [44]:

- Poorly annotated genomes, especially for non-model species.

- Metabolic diversity and the presence of diverse secondary metabolites.

- Complex interaction networks with symbionts in the rhizosphere.

- Plasticity and environmental responsiveness, meaning the same genotype can exhibit different molecular profiles under different conditions [46].

A systematic Multi-Omics Integration (MOI) workflow is recommended to ensure accurate data representation. This can be broken down into three levels [44]:

- Level 1 (Element-based): Unbiased integration using correlation, clustering, or multivariate analysis.

- Level 2 (Pathway-based): Knowledge-driven integration using pathway mapping (e.g., KEGG, MapMan) or co-expression networks.

- Level 3 (Mathematical): Quantitative integration using differential and genome-scale analysis to build predictive models.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table: Key Reagents and Technologies for Multi-Omics Research

| Item / Technology | Function in Multi-Omics Workflow |

|---|---|

| Spatial ATAC–RNA-seq [48] | Enables genome-wide, simultaneous co-profiling of chromatin accessibility and gene expression on the same tissue section. |

| Spatial CUT&Tag–RNA-seq [48] | Allows for the joint profiling of histone modifications (e.g., H3K27me3, H3K27ac) and the transcriptome from the same tissue section. |

| Tn5 Transposase [48] | An enzyme used in epigenomic methods (e.g., ATAC-seq) to simultaneously fragment and tag accessible genomic DNA with adapters. |

| Deterministic Barcoding [48] | A method using microfluidic chips to introduce spatial barcodes onto tissue, assigning spatial coordinates to molecular data. |

| MOFA+ (Multi-Omics Factor Analysis) [47] | A statistical tool for the vertical integration of multiple omics modalities (e.g., mRNA, DNA methylation, chromatin accessibility) from the same samples. |

| GLUE (Graph-Linked Unified Embedding) [47] | A tool based on graph variational autoencoders designed for unmatched integration, using prior biological knowledge to anchor features across omics layers. |

Standardized Workflow for Data Generation and Integration

The following diagram illustrates a generalized, high-level workflow for generating and integrating multi-omics data, from sample preparation to biological insight.

The integration of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and spatial transcriptomics (ST) is revolutionizing plant omics research, enabling unprecedented resolution in studying cellular heterogeneity and spatial organization of gene expression. However, significant variability in quality control procedures, analysis parameters, and metadata reporting often compromises the reliability and reproducibility of findings [50]. This technical support center provides standardized troubleshooting guides and protocols specifically framed within plant natural products research, where understanding the biosynthetic pathways of valuable specialized metabolites is a primary goal [51]. By implementing these standardized workflows, researchers can ensure their data meets FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable), facilitating more robust discovery and validation in plant metabolic pathway elucidation [52] [51].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the most critical quality control checkpoints in scRNA-seq analysis? The most critical QC checkpoints involve filtering based on three key metrics: the number of counts per barcode (count depth), the number of genes per barcode, and the fraction of counts from mitochondrial genes per barcode [53]. Barcodes with low counts/genes and high mitochondrial fractions often represent dying cells or broken membranes, while those with unexpectedly high counts may indicate doublets [53] [54].

2. How can I distinguish true biological signals from technical artifacts in my scRNA-seq data? Technical artifacts including batch effects, ambient RNA, and cell doublets can obscure biological signals. Batch effects arising from different processing conditions should be addressed using integration tools like Seurat, SCTransform, FastMNN, or scVI [54]. Ambient RNA can be mitigated computationally with tools like SoupX, CellBender, and DecontX [54], while doublets can be identified and removed using Scrublet or DoubletFinder [53] [54].

3. My spatial transcriptomics data shows misaligned tissue slices. What solutions are available? Multiple computational tools exist for aligning and integrating multiple ST tissue slices. For homogeneous tissues, statistical mapping tools like PASTE are effective. For more heterogeneous tissues (common in plant samples), graph-based approaches such as SpatiAlign or STAligner often provide more robust alignment [55]. The choice depends on your tissue complexity and experimental design.

4. What metadata is essential for reproducible plant omics studies? Essential metadata includes detailed sample information (collection date, location, tissue type), experimental conditions, processing methodologies (extraction protocols, sequencing platform), and data processing parameters [10] [52]. For plant natural product research, specifically document developmental stage, organ type, and environmental conditions, as these strongly influence specialized metabolism [51]. Standardized templates following MIxS (Minimum Information about any (x) Sequence) checklists are recommended [10] [52].

5. How should I handle differential expression analysis across multiple samples in scRNA-seq? A common mistake is grouping all cells from each condition together and performing differential expression at the single-cell level, which can yield artificially small p-values due to non-independence. Instead, use pseudo-bulk approaches that aggregate counts per sample before testing, thus properly accounting for biological replicates [56].

Troubleshooting Guides

Common scRNA-seq Data Quality Issues and Solutions

Table 1: Troubleshooting scRNA-seq Data Quality

| Problem | Cause | Solution | Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| High mitochondrial read fraction | Dead/dying cells with ruptured cytoplasmic membranes [53] | Filter cells exceeding a threshold (often 10-20%); adjust based on cell type and biological context [54] | Check if removed cells form a distinct cluster in dimensionality reduction plots |

| Cell doublets | Multiple cells sharing the same barcode [57] | Use Scrublet (Python) or DoubletFinder (R) to identify and remove doublets bioinformatically [53] [54] | Confirm the removal of intermediate cell phenotypes that don't align with established lineages |

| Ambient RNA contamination | Free-floating transcripts barcoded alongside intact cells, prevalent in droplet-based methods [50] [54] | Apply computational removal tools such as SoupX, CellBender, or DecontX during preprocessing [54] | Reduction in background gene expression levels and cross-cell-type contamination |

| Batch effects | Technical variations between sequencing runs or experimental batches [57] | Apply batch correction algorithms (e.g., Harmony, Combat, Scanorama) during data integration [57] [54] | Cells of the same type from different batches should co-cluster in UMAP/t-SNE plots |