Plant Synthetic Biology: Engineering Programmable Bio-factories for Pharmaceuticals and Biomedicine

This article explores the transformative role of synthetic biology in reprogramming plant systems for advanced biomedical and pharmaceutical applications.

Plant Synthetic Biology: Engineering Programmable Bio-factories for Pharmaceuticals and Biomedicine

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of synthetic biology in reprogramming plant systems for advanced biomedical and pharmaceutical applications. It details the foundational technologies—from CRISPR-based genome editing to omics-driven pathway discovery—that enable the engineering of plant chassis. We examine methodological advances for producing complex therapeutic molecules, troubleshoot key bottlenecks in transformation and pathway stability, and provide a comparative analysis of plant-based versus microbial production platforms. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current capabilities and future trajectories for using plant synthetic biology to create sustainable, scalable bio-factories for high-value biomolecules.

Core Principles and Technological Foundations of Plant Synthetic Biology

The convergence of DNA synthesis, CRISPR/Cas systems, and computational modeling is revolutionizing plant synthetic biology, creating a powerful toolkit for engineering plant biosystems [1]. This technological triad enables researchers to move beyond simple genetic modifications toward the comprehensive design and construction of novel biological systems in plants. These advancements are pivotal for addressing global challenges in sustainable agriculture, biomedicine, and climate resilience by facilitating the development of plants with enhanced nutritional profiles, improved environmental stress tolerance, and the capacity to produce valuable pharmaceutical compounds [1] [2]. The integration of these technologies follows an iterative Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) framework, which allows for the systematic optimization of complex genetic traits and metabolic pathways [1]. This technical guide examines the principles, applications, and methodologies of these core enabling technologies within the context of modern plant bioscience research.

DNA Synthesis and Assembly in Plant Bioengineering

DNA synthesis technology provides the foundational building blocks for plant synthetic biology by enabling the de novo construction of genetic elements and pathways. This capability allows researchers to bypass the constraints of naturally occurring sequences and create optimized, refactored genetic components tailored for specific functions in plant systems [3]. The synthesis of standardized, modular DNA parts—including promoters, coding sequences, and terminators—has been crucial for assembling complex genetic circuits with predictable behaviors in plant chassis [3].

Advanced DNA assembly techniques now enable the reconstruction of entire plant natural product (PNP) biosynthetic pathways in heterologous hosts. A prominent application is the rapid testing of biosynthetic pathways using transient expression systems in Nicotiana benthamiana, a versatile plant chassis valued for its large leaf biomass and efficient Agrobacterium-mediated transformation [1]. For instance, the reconstruction of the diosmin biosynthetic pathway required the coordinated expression of five to six flavonoid pathway enzymes, resulting in production yields up to 37.7 µg/g fresh weight in tobacco leaves [1]. Similarly, successful pathway reconstructions have been demonstrated for compounds including costunolide, linalool, triterpenoid saponins, and key paclitaxel (anti-cancer) intermediates [1].

Table 1: DNA Synthesis Applications in Plant Metabolic Pathway Engineering

| Application Area | Technical Approach | Key Outcome | Reference Plant Chassis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flavonoid Production | Coordinated expression of 5-6 enzymes (dioxygenases, methyltransferases) | Diosmin production at 37.7 µg/g FW | Nicotiana benthamiana [1] |

| Terpenoid Engineering | Reconstruction of terpenoid precursor pathways | Production of costunolide and linalool | Nicotiana benthamiana [1] |

| Pharmaceutical Intermediates | Expression of complex plant-derived biosynthetic enzymes | Synthesis of paclitaxel precursors | Nicotiana benthamiana [1] |

| Saponin Production | Assembly of triterpenoid biosynthetic gene clusters | Reconstitution of triterpenoid saponin pathways | Nicotiana benthamiana [1] |

Experimental Protocol: Transient Pathway Expression in N. benthamiana

Methodology for Rapid Reconstruction of Plant Natural Product Pathways [1]

Pathway Design and DNA Synthesis: Identify target biosynthetic pathway genes through omics data mining and bioinformatics analysis. Design codon-optimized sequences for plant expression and synthesize individual genetic components.

Vector Assembly: Clone synthesized genes into plant expression vectors under the control of suitable constitutive or inducible promoters. Employ standardized modular cloning systems (Golden Gate, MoClo) for efficient multigene assembly.

Agrobacterium Transformation: Introduce assembled constructs into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strains (e.g., GV3101, LBA4404) using electroporation or freeze-thaw methods. Select positive clones on appropriate antibiotics.

Plant Infiltration: Grow N. benthamiana plants for 4-5 weeks under controlled conditions. Prepare Agrobacterium cultures (OD600 = 0.5-1.0) in infiltration medium (10 mM MES, 10 mM MgCl2, 150 µM acetosyringone). Incubate cultures for 2-4 hours at room temperature with agitation. Infiltrate bacterial suspensions into the abaxial side of leaves using a needleless syringe.

Incubation and Analysis: Maintain infiltrated plants for 5-7 days post-infiltration. Harvest leaf tissue for metabolite extraction and analysis via LC-MS/GC-MS to quantify pathway intermediates and final products.

CRISPR/Cas Systems for Precision Plant Genome Editing

CRISPR/Cas systems have emerged as the foremost technology for precision genome engineering in plants, enabling targeted modifications that range from simple gene knockouts to precise nucleotide substitutions [4] [5]. These systems function as programmable nucleases that create double-strand breaks (DSBs) at specific genomic locations, harnessing the cell's endogenous DNA repair mechanisms—either error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed repair (HDR)—to introduce desired genetic changes [4]. The classification of CRISPR-Cas systems includes two primary classes: Class 1 (types I, III, and IV) utilizing multi-subunit effector complexes, and Class 2 (types II, V, and VI) employing single-protein effectors such as Cas9, Cas12, and Cas13 [5].

Recent advancements have substantially diversified the plant genome editing toolbox beyond the commonly used Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9). Novel CRISPR-associated proteins including Cas12a, Cas12f, and Cas13 offer distinct PAM specificities, smaller molecular sizes for easier delivery, and expanded targeting capabilities including RNA interference [5] [6]. The development of base editing and prime editing systems enables precise nucleotide conversions without requiring double-strand breaks, significantly expanding the scope of achievable edits while reducing unintended mutations [6]. Furthermore, AI-driven protein design has begun generating novel CRISPR effectors; the OpenCRISPR-1 system, designed using large language models trained on 1.26 million CRISPR operons, demonstrates editing efficiency comparable to SpCas9 while being 400 mutations distant from any natural sequence [7].

Table 2: CRISPR/Cas Systems and Their Applications in Plant Genome Engineering

| System Type | Signature Protein | Target Molecule | Key Features & Plant Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type II | Cas9 | DNA | Requires tracrRNA; most widely used for gene knockouts; employed in tomato GABA enhancement [1] [5] |

| Type V | Cas12 (Cpf1) | DNA | Single RNA guide; staggered DNA cuts; multiplex editing capability [5] [6] |

| Type VI | Cas13 | RNA | RNA targeting; knockdown without genomic alteration; viral interference [5] |

| Base Editors | dCas9-fusion | DNA | Precision C>T or A>G conversions without DSBs; point mutation correction [6] |

| Prime Editors | Cas9-reverse transcriptase | DNA | Targeted insertions, deletions, and all base-to-base conversions; template-driven editing [6] |

| AI-Designed | OpenCRISPR-1 | DNA | Novel effector with high specificity and efficiency; compatible with base editing [7] |

Experimental Protocol: CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Genome Editing in Plants

Methodology for Targeted Gene Knockout in Tomato [1]

Target Selection and gRNA Design: Identify target gene sequences (e.g., SlGAD2 and SlGAD3 for GABA biosynthesis). Design 20-nucleotide guide RNA sequences adjacent to 5'-NGG-3' PAM sites. Validate target specificity to minimize off-target effects.

Vector Construction: Clone gRNA expression cassettes into CRISPR/Cas9 binary vectors under the control of U6 or U3 Pol III promoters. Assemble multigene constructs for multiplexed editing when targeting multiple loci.

Plant Transformation: Introduce CRISPR constructs into tomato explants via Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. For tomato, use cotyledon or hypocotyl explants from 7-10 day old seedlings. Co-cultivate with Agrobacterium for 2-3 days, then transfer to selection media containing antibiotics.

Regeneration and Selection: Regenerate transformed tissues on shoot induction media followed by root induction media. Screen putative transformants using PCR and restriction enzyme digestion assays.

Mutation Analysis: Genotype T0 plants by sequencing the target regions to detect indel mutations. Evaluate editing efficiency and specificity. Measure phenotypic outcomes (e.g., 7-15 fold GABA accumulation in edited tomato lines) [1].

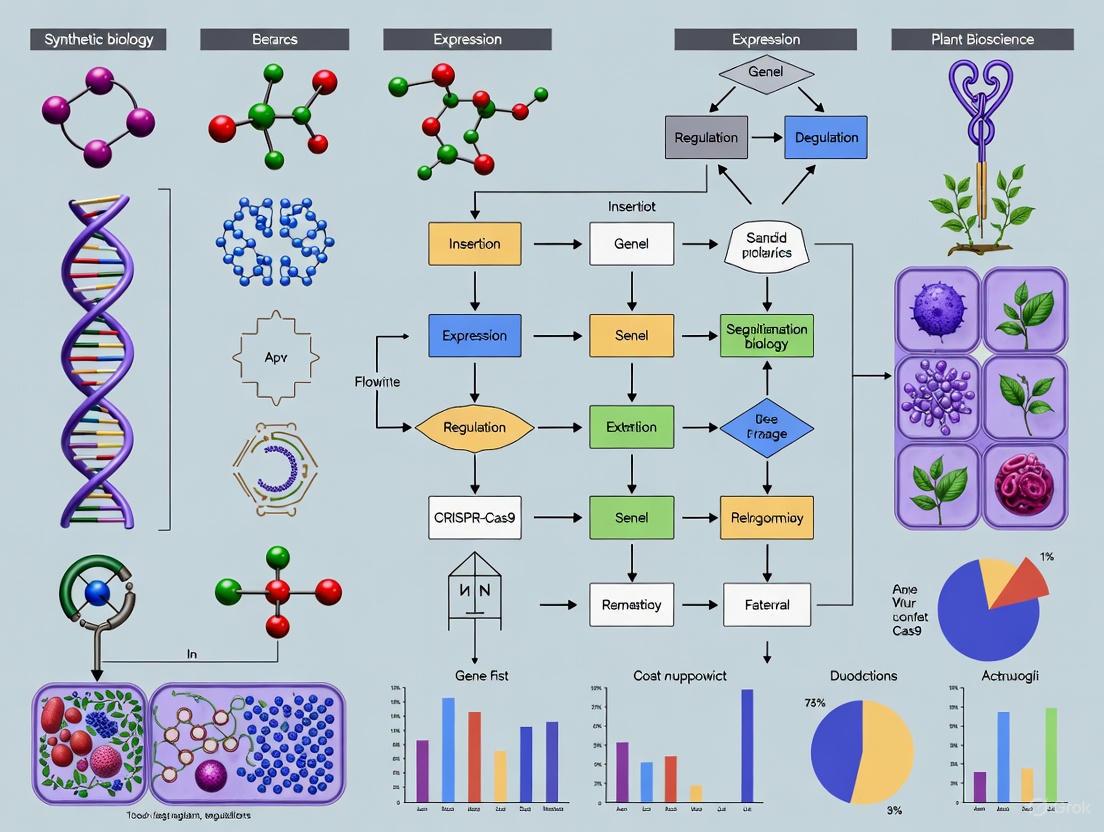

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanism of the CRISPR/Cas9 system for creating targeted gene knockouts:

Computational Modeling and Design in Plant Synthetic Biology

Computational modeling provides the predictive framework essential for rational design in plant synthetic biology, transforming the field from trial-and-error experimentation to forward-engineered biological systems [3]. Modeling approaches span multiple scales, from predicting the behavior of individual genetic parts to simulating complex metabolic networks and synthetic gene circuits. The integration of multi-omics data (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) with computational models enables the reconstruction of complete biosynthetic networks and identification of key regulatory nodes for engineering interventions [1].

A significant advancement in computational design is the application of large language models (LMs) for protein engineering. Researchers have successfully generated novel CRISPR-Cas effectors by fine-tuning LMs on the "CRISPR-Cas Atlas"—a curated dataset of over 1.2 million CRISPR operons mined from 26 terabases of microbial genomes and metagenomes [7]. These AI-designed editors, such as OpenCRISPR-1, exhibit comparable or improved activity and specificity relative to natural Cas9 proteins while being highly divergent in sequence, demonstrating the power of computational approaches to expand the molecular toolkit available for plant engineering [7].

Computational tools also enable the quantitative characterization of genetic parts, a prerequisite for constructing predictable genetic circuits. By measuring parameters such as promoter strength, ribosome binding site efficiency, and terminator activity, researchers can develop mathematical models that predict the input-output relationships (transfer functions) of genetic components [3]. This quantitative understanding allows for the in silico design of synthetic circuits with predefined behaviors before implementation in plant systems.

Experimental Protocol: DBTL Framework for Plant Metabolic Engineering

Methodology for Design-Build-Test-Learn Cycles in Plant Synthetic Biology [1]

Design Phase: Utilize multi-omics data to identify biosynthetic pathways and key regulatory elements. Apply computational modeling to predict flux distributions and potential bottlenecks. Select appropriate genetic parts based on quantitative characterization data.

Build Phase: Assemble designed genetic constructs using standardized modular cloning systems. Transform constructs into plant chassis (e.g., N. benthamiana for transient expression or target crop for stable transformation) via Agrobacterium-mediated delivery or other transformation methods.

Test Phase: Analyze transformants using targeted metabolomics (LC-MS, GC-MS) to quantify pathway intermediates and products. Evaluate system performance under different growth conditions and temporal patterns. Assess genetic stability and potential unintended effects.

Learn Phase: Apply computational tools to analyze experimental results and refine model parameters. Identify limitations and failure modes. Use insights to inform redesign strategies for subsequent DBTL cycles, progressively optimizing system performance.

The following diagram illustrates the iterative DBTL framework central to modern plant synthetic biology:

Integrated Workflow: Pathway Engineering via Synergistic Technology Application

The full potential of plant synthetic biology emerges when DNA synthesis, CRISPR/Cas systems, and computational modeling operate synergistically within integrated workflows. This integration is exemplified by recent advances in plant metabolic engineering for the production of high-value compounds. The workflow begins with computational mining of multi-omics datasets to identify candidate genes involved in specialized metabolite biosynthesis, followed by functional validation of these candidates in heterologous systems [1]. Subsequently, CRISPR/Cas systems are employed to engineer the native plant metabolism to enhance precursor supply or remove competing pathways, while synthesized transgenes are introduced to reconstruct or augment target pathways.

A key consideration in integrated plant engineering is the quantitative understanding of transformation dynamics. Recent research has revealed density-dependent antagonistic interactions during Agrobacterium-mediated transformation, where increasing total bacterial density reduces the transformation efficiency per bacterium [8]. This finding has led to the development of modified transformation models incorporating an "antagonism correction parameter" and engineering solutions such as the dual binary vector (BiBi) system to overcome these limitations for complex pathway reconstitution [8].

The following diagram illustrates an integrated workflow for plant metabolic pathway engineering:

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of plant synthetic biology approaches requires a comprehensive toolkit of research reagents and biological materials. The following table details key resources for conducting experiments in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Plant Synthetic Biology

| Reagent/Material | Function | Examples & Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Plant Chassis Systems | Host organisms for pathway engineering and trait testing | Nicotiana benthamiana (transient expression), staple crops (rice, tomato, poplar) for stable transformation [1] |

| Binary Vectors | T-DNA delivery systems for plant transformation | pCAMBIA, pGreen, pEAQ vectors; BiBi system for complex pathway expression [8] |

| Agrobacterium Strains | Bacterial delivery vehicle for plant genetic transformation | GV3101, LBA4404, EHA105; engineered for improved efficiency [1] [8] |

| Modular Cloning Systems | Standardized assembly of genetic constructs | Golden Gate (MoClo) systems for plant synthetic biology [3] |

| CRISPR/Cas Systems | Precision genome editing tools | Cas9, Cas12a, base editors, prime editors; AI-designed OpenCRISPR-1 [7] [5] [6] |

| Fluorescent Reporters | Visual markers for transformation efficiency and gene expression | sfGFP, mCherry, tagBFP2 with nuclear localization signals [8] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Computational analysis and design resources | Pathway prediction algorithms, gRNA design tools, protein language models [1] [7] |

| Analytical Standards | Metabolite quantification and validation | Reference compounds for LC-MS/GC-MS analysis of pathway products [1] |

The Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle is a systematic, iterative framework central to synthetic biology, enabling the engineering of biological systems for predictable outcomes such as the production of valuable compounds [@citation:1]. This framework provides a structured approach to overcome the traditional ad-hoc practices that have long hindered biological engineering, leading to significantly shortened development times [@citation:1]. In contrast to traditional molecular biology, which typically modifies existing genes, synthetic biology enables the bottom-up design of multigene networks, regulatory modules, and synthetic circuits tailored to specific goals [@citation:4]. The cycle begins with the Design phase, where researchers define objectives and design biological parts or systems using computational models and domain knowledge. The Build phase involves synthesizing DNA constructs and assembling them into vectors, which are then introduced into a characterization system such as bacteria, plants, or cell-free platforms. The Test phase experimentally measures the performance of the engineered constructs, and the Learn phase analyzes this data to inform the next design iteration [@citation:3]. This recursive process is repeated until a biological system meets the desired specifications, streamlining efforts to build functional biological systems [@citation:1] [9].

The application of the DBTL cycle is particularly valuable for addressing complex traits in plants, such as drought tolerance, disease resistance, and yield, which are controlled by multiple genes [@citation:7]. Within the emerging bioeconomy, plants serve as renewable and cost-effective sources of foods, fuels, and chemicals, and the DBTL cycle provides the necessary framework for their systematic enhancement [@citation:7]. Recent advances, particularly the integration of machine learning (ML) and automation, are transforming the DBTL cycle from a largely manual, time-consuming process into a powerful, high-throughput engine for biological design [@citation:1] [10] [11]. These advancements are paving the way for a more predictive and efficient approach to bioengineering, with profound implications for agriculture, therapeutics, and sustainable manufacturing.

The Core Components of the DBTL Cycle

Design

The Design phase is the foundational first step where researchers define the genetic blueprint for the biological system. This involves selecting and arranging standardized biological parts (e.g., promoters, coding sequences, terminators) to achieve a desired function [@citation:2]. In modern synthetic biology, this phase heavily relies on computational tools and models. For metabolic engineering, the objective is often to design a pathway that maximizes the flux toward a product of interest [@citation:5]. The design process can target individual genetic parts or complex multigene pathways. For plants, this often involves multigene engineering (MGE), which is the simultaneous ectopic expression, up/down-regulation, or editing of multiple genes to enhance complex traits [@citation:7].

Build

The Build phase translates the in silico design into a physical biological reality. This involves the synthesis and assembly of DNA constructs, which are then introduced into a living chassis (such as bacteria, yeast, or plants) or cell-free systems [@citation:3]. A key enabler of this phase is the emphasis on modular design and automation. Modular DNA parts allow for the assembly of a greater variety of constructs by interchanging individual components, while automation reduces the time, labor, and cost of generating multiple constructs [@citation:2]. High-throughput robotic systems and advanced DNA assembly techniques, such as ligase chain reaction (LCR) and uracil-specific excision reagent (USER) cloning, are increasingly used to accelerate this process [@citation:9]. In plant bioengineering, the Build phase involves DNA assembly and plant transformation to create the engineered lines [@citation:7].

Test

The Test phase is dedicated to the molecular, biochemical, and physiological characterization of the built biological system to determine its performance [@citation:7]. This involves a variety of assays to measure the output, such as the production titer of a target molecule, or the profiling of multi-omics data (e.g., transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) [@citation:1]. Automation is critical in this phase to achieve the necessary throughput, reliability, and reproducibility. High-throughput screening methods, laboratory robotics, and automated data analysis pipelines are employed to test hundreds or thousands of constructs efficiently [@citation:8]. For metabolic engineering, the key performance metrics are often summarized as TYR: Titer, Yield, and Rate *[@citation:5]*.

Learn

The Learn phase is the analytical core of the cycle, where data from the Test phase is used to extract insights and generate knowledge that will inform the next design round. Traditionally, this involved statistical analysis and comparison to the initial design objectives [@citation:3]. Today, machine learning (ML) is revolutionizing this phase by learning the underlying regularities in experimental data to predict system behavior without requiring a full mechanistic understanding [@citation:1] [10]. This is particularly powerful in biological systems where complexity often precludes accurate first-principles modeling. The learning can be used to refine models, identify bottlenecks, and predict which new designs have the highest probability of success in the next iteration [@citation:5] [12].

Table 1: Core Phases of the DBTL Cycle and Their Key Activities

| DBTL Phase | Primary Objective | Key Activities & Technologies |

|---|---|---|

| Design | Create a genetic blueprint to achieve a desired function | Computational modeling, part selection, multigene pathway design, promoter engineering [@citation:2] [13] |

| Build | Construct the physical biological system | DNA synthesis & assembly, modular cloning, plant transformation, automation [@citation:2] [11] |

| Test | Characterize the performance of the built system | High-throughput screening, multi-omics profiling (proteomics, metabolomics), biosensors [@citation:1] [14] |

| Learn | Analyze data to inform the next design iteration | Machine learning, statistical analysis, model refinement, uncertainty quantification [@citation:1] [10] |

The Machine Learning-Powered DBTL Cycle

Machine learning (ML) has emerged as a transformative force within the DBTL cycle, particularly in the Learn and Design phases, by providing powerful predictive capabilities that guide engineering decisions [@citation:1] [10].

Machine Learning in the Learn Phase

The Learn phase has traditionally been the most weakly supported part of the cycle, but ML directly addresses this gap [@citation:1]. ML algorithms are trained on experimental data to statistically link input variables (e.g., proteomics data, promoter sequences) to output responses (e.g., production of a target molecule) [@citation:1]. A key tool exemplifying this approach is the Automated Recommendation Tool (ART). ART uses an ensemble of ML models and probabilistic modeling to provide recommendations for the next cycle's strains to build, alongside predictions of their production levels [@citation:1]. Instead of providing a single prediction, ART quantifies uncertainty by providing a full probability distribution of possible outcomes, which is crucial for making informed decisions with sparse and expensive biological data [@citation:1] [15].

Machine Learning in the Design Phase

ML is also shifting the paradigm by moving "Learning" to the beginning of the cycle. With the advent of large biological datasets and sophisticated models, it is now possible to perform zero-shot design, where ML models generate functional designs without the need for iterative DBTL cycling [@citation:3]. This is often referred to as the LDBT (Learn-Design-Build-Test) paradigm [@citation:3]. Protein language models (e.g., ESM, ProGen), trained on millions of protein sequences, can predict beneficial mutations and infer protein function directly from sequence, enabling the design of novel biocatalysts without additional experimental training data [@citation:3]. Similarly, structure-based models like ProteinMPNN can design sequences that fold into a desired backbone, leading to a nearly 10-fold increase in design success rates when combined with structure assessment tools like AlphaFold [@citation:3].

Hybrid AI Approaches

For complex applications like plant engineering, Hybrid AI is becoming essential. This approach combines different AI paradigms: the transparency and logical structure of symbolic AI (e.g., knowledge graphs) with the pattern-finding capabilities of machine learning and the creative potential of generative AI and large language models (LLMs) [@citation:4]. Knowledge graphs provide organized maps of biological relationships, which, when integrated with LLMs, enable deeper, context-aware analysis and more reliable design generation [@citation:4]. This hybrid strategy is particularly suited for integrating multi-omics, phenotypic, and environmental information to tackle complex traits in crops [@citation:4].

Figure 1: The ML-Augmented DBTL Cycle. Machine learning powers the Learn phase and enables zero-shot design in the Design phase, creating a more predictive and efficient engineering loop.

Implementing DBTL in Plant Bioscience: A Detailed Workflow

The application of the DBTL cycle in plant bioscience requires a tailored workflow to address the unique challenges of plant systems, such as longer life cycles and complex multigene traits. The following section outlines a detailed protocol and provides a toolkit for implementation.

Experimental Protocol: A Knowledge-Driven DBTL for Metabolic Engineering

The following protocol, inspired by successful DBTL implementations, describes a knowledge-driven approach for optimizing a metabolic pathway in a plant chassis. This methodology integrates upstream in vitro testing to de-risk the initial design, accelerating the entire development process [@citation:10].

Phase 1: In Vitro Pathway Prototyping (Pre-DBTL Knowledge Gathering)

- Objective: Bypass whole-cell constraints to rapidly test enzyme combinations and identify potential bottlenecks before in vivo strain construction.

- Cell-Free Protein Synthesis (CFPS):

- Prepare a crude cell lysate system from the plant chassis or a model microorganism (e.g., E. coli).

- Clone genes of interest (e.g., pathway enzymes HpaBC and Ddc for dopamine production) into expression plasmids under an inducible promoter [@citation:10].

- Express the enzymes individually and in combination using the CFPS system.

- Assay: Supplement the CFPS reaction buffer with the pathway precursor (e.g., L-tyrosine) and key cofactors (e.g., FeCl₂, vitamin B6). Incubate and quantify intermediate and final product formation (e.g., L-DOPA, dopamine) using HPLC or LC-MS [@citation:10].

- Data Analysis: Determine the relative expression levels and activities of the enzymes. Identify optimal enzyme ratios that maximize pathway flux in the simplified in vitro environment.

Phase 2: First Full DBTL Cycle

- Design (D1):

- Based on the in vitro results, design a bicistronic construct for the metabolic pathway.

- To fine-tune the relative expression levels of the two enzymes in vivo, design a library of Ribosome Binding Site (RBS) variants for one or both genes. Tools like the UTR Designer can be used to modulate the Shine-Dalgarno sequence while minimizing changes to mRNA secondary structure [@citation:10].

- Build (B1):

- Use high-throughput DNA assembly (e.g., Golden Gate assembly) to clone the RBS library and the pathway genes into a plant transformation vector.

- Transform the constructs into Agrobacterium and subsequently into the plant chassis (e.g., Nicotiana benthamiana for transient expression or generate stable transgenic lines).

- Test (T1):

- Cultivate the engineered plant lines in a controlled environment.

- Induce gene expression and sample tissues at multiple time points.

- Quantification: Extract metabolites and measure the titer of the target compound (e.g., dopamine) using LC-MS/MS. Normalize the production to biomass (mg/g) [@citation:10].

- For a subset of high-performing lines, perform targeted proteomics to verify the correlation between designed RBS strength, enzyme concentration, and product titer.

- Learn (L1):

- Train a machine learning model (e.g., Random Forest or Gradient Boosting, which perform well in low-data regimes [@citation:5]) on the dataset linking RBS sequences to product titer.

- Use the model to predict the performance of untested RBS variants and identify the most promising designs for the next cycle.

Phase 3: Iterative DBTL Cycling

- Design (D2): Use the model from L1 to design a second, more refined RBS library focused on the predicted high-performance region of the sequence space.

- Build (B2) & Test (T2): Construct and test the new library. The testing should include a replication of the best-performing strain from the first cycle as an internal benchmark.

- Learn (L2): Update the ML model with the new experimental data. This iterative process continues until the performance specifications (e.g., a target titer) are met.

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for DBTL in Plant Metabolic Engineering

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Description | Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Cell-Free Protein Synthesis (CFPS) System | Crude cell lysate containing transcriptional/translational machinery for in vitro protein expression [@citation:3] [12]. | Phase 1: Rapidly test enzyme functionality and pathway flux without live cells. |

| Golden Gate Assembly | A modular, type IIS restriction enzyme-based DNA assembly method that allows for seamless, high-throughput cloning [@citation:9]. | Phase 2 (B1): Assemble multigene constructs and RBS libraries efficiently. |

| RBS Library | A set of DNA sequences with variations in the Ribosome Binding Site to systematically fine-tune translation initiation rates [@citation:10]. | Phase 2 (D1): Precisely control the relative expression levels of pathway enzymes. |

| Automated Recommendation Tool (ART) | A machine learning tool that uses probabilistic modeling to recommend strains for the next DBTL cycle [@citation:1]. | Phase 2 (L1) & Phase 3: Analyze data and provide model-driven recommendations for subsequent designs. |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid Chromatography with Tandem Mass Spectrometry, a highly sensitive analytical technique for identifying and quantifying metabolites. | All Test Phases: Accurately measure the concentration of the target product and pathway intermediates. |

Figure 2: Knowledge-Driven DBTL Workflow. This protocol uses upstream in vitro testing to de-risk the initial design, creating a more efficient and mechanistic path to an optimized plant line.

The DBTL cycle, supercharged by machine learning and automation, represents a cornerstone of modern predictive engineering in biology. By transitioning from ad-hoc experimentation to a systematic, iterative framework, it dramatically accelerates the development of biological systems with desired functions [@citation:1]. For plant bioscience, this approach is indispensable for tackling the multigene complexity of key agricultural traits, from stress resilience to metabolic engineering for the bioeconomy [@citation:4] [13]. The integration of hybrid AI, cell-free prototyping, and automated biofoundries is steadily shifting the paradigm from empirical iteration toward true rational design [@citation:3] [11]. As these tools and data sets continue to mature, the DBTL cycle will undoubtedly become the primary engine for engineering the next generation of sustainable agricultural and industrial solutions.

The elucidation of plant biosynthetic pathways is fundamental to advancing a sustainable bioeconomy by enabling access to complex natural products through synthetic biology [16]. Plant natural products (PNPs), also known as plant secondary metabolites, play indispensable roles in ecological balance, human health, industrial applications, and biodiversity conservation [17]. These specialized metabolites include a vast array of chemically diverse compounds with significant pharmaceutical and nutraceutical value, such as the antimalarial precursor artemisinin and the anticancer drug paclitaxel [1] [18]. However, a critical challenge persists: the biosynthetic routes for the majority of these valuable compounds remain largely undetermined, creating a major bottleneck for their sustainable production through engineered biological systems [19].

In the post-genomic era, the integration of multiple omics technologies—genomics, transcriptomics, and metabolomics—has emerged as a transformative approach for deciphering these complex biosynthetic pathways [20] [21]. This integrated methodology leverages the complementary strengths of each omics discipline to bridge the gap between genetic information and metabolic phenotypes. While single-omics approaches provide valuable but fragmented insights, multi-omics integration offers a systems-level perspective that can accelerate pathway discovery by establishing correlations between gene expression, protein function, and metabolite accumulation [20]. The power of this integrated approach lies in its ability to mitigate false positives, refine validation targets, and provide mutual verification of findings across different molecular levels [20].

The application of integrated omics is particularly vital within the framework of plant synthetic biology, which aims to engineer plant systems for enhanced production of valuable biomolecules [1]. By providing comprehensive insights into plant metabolic networks, multi-omics data guides the rational design of synthetic pathways and informs the engineering of plant chassis or microbial cell factories for sustainable bioproduction [1] [22]. This technical guide explores the core principles, methodologies, and applications of omics integration for plant biosynthetic pathway discovery, with a specific focus on its pivotal role in advancing synthetic biology applications in plant bioscience research.

Core Omics Technologies and Their Roles in Pathway Elucidation

Genomic Foundations for Pathway Discovery

Genomics provides the fundamental blueprint for biosynthetic pathway discovery by cataloging an organism's complete genetic repertoire. Advancements in sequencing technologies have been pivotal, transitioning from early methods to today's high-quality, chromosome-scale genome assemblies [17] [18]. Exceptional platforms like PacBio's Single-Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing and Oxford Nanopore Technologies now enable the resolution of complex genomic regions previously inaccessible with short-read technologies [20]. These technological leaps are particularly significant for plant species, whose genomes often contain extensive repetitive regions and complex gene families involved in specialized metabolism [17].

A key genomic strategy for pathway identification involves the detection of Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs)—physical groupings of genes encoding enzymes that participate in the same biosynthetic pathway [18]. While common in bacterial and fungal systems, plant BGCs are increasingly being recognized for their role in synthesizing specific classes of natural products, such as terpenes, alkaloids, and cyanogenic glucosides [18]. Genomic mining for BGCs utilizes tools like plantiSMASH, which can identify co-localized biosynthetic genes and predict their chemical products based on domain analysis and comparative genomics [18]. Beyond BGC identification, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) leverage natural genetic variation across different plant accessions to link specific genomic regions with metabolic traits, helping to pinpoint candidate genes controlling the production of valuable specialized metabolites [17].

Transcriptomic Insights into Gene Expression Dynamics

Transcriptomics captures the dynamic expression of RNA molecules, serving as a crucial bridge between the static genome and the functional proteome [20] [21]. By quantifying genome-wide mRNA expression patterns under specific conditions—such as different tissues, developmental stages, or environmental treatments—transcriptomics can identify co-expression networks where genes encoding enzymes in the same pathway show correlated expression profiles [1] [17]. This approach has proven particularly powerful for discovering novel genes in plant biosynthetic pathways, especially when combined with metabolomic data to establish strong correlations between gene expression and metabolite accumulation [1] [20].

The evolution of transcriptomic technologies has progressed from hybridization-based methods (e.g., DNA microarrays) to sequencing-based approaches, with RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) emerging as the current gold standard due to its high throughput, single-nucleotide resolution, and ability to detect novel transcripts and alternative splicing events [21]. The typical RNA-seq workflow involves RNA extraction, fragmentation, cDNA synthesis, adapter ligation, PCR enrichment, and high-throughput sequencing, followed by sophisticated bioinformatic analysis of the resulting reads [21]. More recently, single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has enabled transcriptomic profiling at single-cell resolution, uncovering cellular heterogeneity and cell type-specific expression patterns critical for understanding the spatial organization of biosynthetic pathways within plant tissues [21].

Metabolomic Profiling of Pathway Outputs

Metabolomics provides the most functional readout of cellular processes by comprehensively profiling the low-molecular-weight metabolites (<1 kDa) within a biological system [21]. As the final products of biochemical processes catalyzed by enzymes, metabolites offer direct molecular insights into the biochemistry of organisms at a given time and under specific conditions [20]. A key advantage of metabolomics lies in its hypothesis-free nature, enabling unbiased metabolite profiling across diverse plant species without prior biochemical or genetic knowledge [21].

Current metabolomic workflows rely on complementary analytical platforms, each with distinct strengths and applications in pathway discovery [21]. Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) has become the most widely used platform due to its broad coverage of polar and non-polar compounds, including lipids and phenolic acids, without requiring derivatization [16] [21]. Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) excels in profiling thermally stable, volatile metabolites through chemical derivatization, offering high resolution and reproducibility for primary metabolites [21]. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy provides valuable structural information with minimal sample preparation but has lower sensitivity compared to MS-based methods [21]. Capillary Electrophoresis-Mass Spectrometry (CE-MS) specializes in separating highly polar and ionic compounds like amino acids and organic acids based on their charge-to-mass ratio in an electric field [21].

Table 1: Key Analytical Platforms in Metabolomics

| Platform | Key Applications | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| LC-MS | Broad detection of polar/non-polar compounds (e.g., lipids, phenolic acids) | No derivatization required; high sensitivity | Matrix effects can suppress ionization |

| GC-MS | Volatile and thermally stable metabolites | High resolution and reproducibility | Requires chemical derivatization |

| NMR | Structural elucidation of metabolites | Minimal sample preparation; quantitative | Lower sensitivity; cannot detect trace metabolites |

| CE-MS | Highly polar and ionic compounds (e.g., amino acids, organic acids) | Efficient separation of charged molecules | Limited to ionic/polar compounds |

Advanced data analysis strategies have significantly enhanced metabolomic capabilities for pathway discovery. Molecular networking, based on tandem MS (MS/MS) data, groups structurally related metabolites by comparing their fragmentation patterns, enabling the visualization of chemical relationships and the annotation of unknown compounds within the context of known metabolites [16] [18]. Reaction pair analysis identifies pairs of metabolites that could be interconverted by a single enzymatic reaction, suggesting potential substrate-product relationships within pathways [16]. When integrated with genomic and transcriptomic data, these approaches create powerful frameworks for linking genes to metabolites through shared expression patterns.

Integrated Omics Workflows for Pathway Discovery

Conceptual Framework and Experimental Design

The integration of genomics, transcriptomics, and metabolomics follows a systematic workflow designed to progressively narrow candidate genes and validate their functions within biosynthetic pathways. This conceptual framework leverages the complementary nature of these technologies to establish tripartite correlations between genomic loci, gene expression patterns, and metabolite abundances [17]. A typical integrated omics workflow begins with sample selection from multiple tissues, developmental stages, or environmental treatments to maximize molecular diversity, followed by parallel genomic/transcriptomic sequencing and metabolomic profiling [17] [18]. Bioinformatic integration then identifies associations between co-expressed genes and associated metabolites, prioritizing candidate genes for functional validation in heterologous systems [1] [18].

The power of this integrated approach is magnified when applied to plant populations with natural genetic variation or to experimental treatments that induce metabolic changes. For instance, studying different cultivars with distinct metabolic profiles or applying elicitors (e.g., jasmonate) that activate specialized metabolism can reveal consistent patterns of correlation between specific transcripts and metabolites across multiple conditions [17]. This multi-condition sampling strategy significantly enhances the statistical confidence in predicted gene-metabolite relationships and helps filter out false positives that might arise from random correlations in single-condition experiments.

Data Integration and Bioinformatics Strategies

Several sophisticated bioinformatic strategies have been developed to integrate multi-omics data for pathway discovery. Co-expression analysis represents one of the most widely used approaches, constructing networks where genes (nodes) are connected based on the similarity of their expression profiles across multiple samples [17]. When metabolites are included as additional nodes in these networks, strong connections between specific metabolites and genes can suggest enzymatic relationships, particularly when the genes encode enzymes with domains known to catalyze reactions consistent with the metabolic transformation [17] [18].

Phylogenetic analysis provides another powerful integration strategy by identifying orthologous genes across related species that produce similar metabolites, or conversely, detecting gene family expansions in lineages that have evolved particular metabolic capabilities [17]. For example, the discovery of triterpene biosynthetic pathways in the apple tribe was facilitated by phylogenetic analysis that revealed how polyploidy events led to the diversification of oxidosqualene cyclase genes, creating new metabolic functions [17].

Machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI) approaches are increasingly revolutionizing multi-omics data integration [16] [18]. Deep neural networks can learn complex patterns from large, heterogeneous omics datasets to predict gene functions and pathway associations with unprecedented accuracy [18]. AI-driven tools can also predict metabolite structures from mass spectrometry data and propose potential biosynthetic routes based on known biochemical transformations [16] [18]. These computational approaches are particularly valuable for prioritizing the most promising candidate genes for labor-intensive experimental validation, dramatically accelerating the pathway discovery pipeline.

Table 2: Key Bioinformatics Tools for Multi-Omics Integration in Pathway Discovery

| Tool Type | Representative Tools | Primary Function | Application in Pathway Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Co-expression Analysis | WGCNA, CYTOSCAPE | Identify correlated gene expression patterns | Find genes co-expressed with metabolite abundance |

| Molecular Networking | GNPS, MetGem | Group related metabolites by MS/MS fragmentation | Visualize chemical relationships; annotate unknowns |

| Pathway Databases | KEGG, PlantCyc | Curated biochemical pathway knowledge | Map discovered metabolites to known pathways |

| Genome Mining | plantiSMASH, antiSMASH | Identify biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) | Discover co-localized biosynthetic genes |

| AI-Prediction | MSNovelist, MolDiscovery | Predict structures and biosynthetic relationships | Propose novel pathway structures from MS data |

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual workflow for integrated omics pathway discovery, showing how data from different omics layers are combined to generate candidate genes for experimental validation:

Experimental Validation and Synthetic Biology Applications

Heterologous Expression Systems for Pathway Validation

Once candidate biosynthetic genes are identified through integrated omics, they require experimental validation to confirm their functions and reconstruct complete pathways. Heterologous expression systems are indispensable for this validation step, allowing researchers to express plant biosynthetic genes in genetically tractable hosts [1]. These systems provide a controlled environment for testing enzyme activities, identifying pathway intermediates, and producing target metabolites that may be undetectable in the original plant source due to low abundance or transient accumulation [1].

Among plant-based heterologous systems, Nicotiana benthamiana has emerged as a particularly valuable platform for several reasons: its large leaves provide substantial biomass, it exhibits rapid growth, and it supports highly efficient Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression [1]. This system enables rapid testing of multiple gene combinations without the need for stable transformation, dramatically accelerating the validation process [1]. Successful examples of pathway reconstruction in N. benthamiana include the production of flavonoids such as diosmin (requiring coordinated expression of five to six enzymes) [1], costunolide, linalool [1], triterpenoid saponins [1], and key intermediates of the anticancer drug paclitaxel [1].

Microbial hosts like Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae continue to play important roles in validating plant biosynthetic genes, particularly for characterizing individual enzyme activities and optimizing precursor supply [1] [22]. However, microbial systems often face challenges in expressing functional plant cytochrome P450 enzymes—which frequently catalyze key oxidation steps in plant specialized metabolism—and may lack necessary cellular compartmentalization or cofactors [1]. Plant-based systems like N. benthamiana naturally accommodate these plant-specific features, making them increasingly preferred for validating complete pathways discovered through omics approaches.

Case Studies in Pathway Discovery and Engineering

Several compelling case studies demonstrate the power of integrated omics for discovering and engineering plant biosynthetic pathways. In tomato, integrated transcriptomics and metabolomics identified two glutamate decarboxylase genes (SlGAD2 and SlGAD3) expressed during fruit development [1]. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated editing of these genes increased gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) accumulation by 7- to 15-fold, demonstrating how targeted genome editing can enhance the production of functional compounds guided by omics data [1].

In another example, researchers applied co-expression analysis of transcriptomic and metabolomic data to identify candidate genes involved in tropane alkaloid biosynthesis, followed by functional validation of these candidates in yeast [1]. This integrated approach significantly accelerated pathway discovery by efficiently decoding complex plant metabolic networks and overcoming the traditional bottleneck of labor-intensive genetic screening [1].

The following diagram illustrates the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle that frames the iterative process of pathway discovery and optimization in synthetic biology:

For the biosynthesis of diosmin, a flavonoid with pharmaceutical value, integrated omics guided the reconstruction of a complex pathway requiring the coordinated expression of five to six enzymes, including dioxygenases and methyltransferases, in N. benthamiana [1]. This engineered system achieved diosmin production at levels up to 37.7 µg/g fresh weight, demonstrating the potential of omics-guided synthetic biology for producing valuable plant natural products [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Successful implementation of integrated omics approaches requires access to specialized research reagents, analytical platforms, and bioinformatic tools. The following table summarizes key solutions essential for conducting multi-omics research in plant biosynthetic pathway discovery:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Integrated Omics Studies

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Key Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NovaSeq, PacBio Sequel, Oxford Nanopore | Genomic and transcriptomic sequencing | Long-read technologies essential for complex plant genomes |

| Mass Spectrometry Systems | LC-MS/MS, GC-MS, CE-MS systems | Metabolite separation and detection | High-resolution tandem MS needed for molecular networking |

| Bioinformatic Tools | GNPS, XCMS, MS-DIAL, MZmine | Metabolomic data processing | Enable peak detection, alignment, and metabolite annotation |

| Heterologous Expression Systems | Nicotiana benthamiana, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Escherichia coli | Functional validation of candidate genes | Plant systems better for complex pathways with P450s |

| Genome Editing Tools | CRISPR/Cas9, base editors, prime editors | Targeted gene knockout/editing | Verify gene function in native plant hosts |

| Pathway Databases | KEGG, PlantCyc, MIBiG | Reference pathway information | Curated knowledge of known biosynthetic pathways |

| Co-expression Tools | plantiSMASH, CYTOSCAPE, WGCNA | Identify correlated gene expression | Find genes with similar patterns across conditions |

Future Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

The field of integrated omics for plant pathway discovery is rapidly evolving, driven by technological advancements in sequencing, mass spectrometry, and computational biology. Emerging approaches such as single-cell omics are poised to revolutionize our understanding of plant metabolism by resolving the cellular heterogeneity that has traditionally been obscured in bulk tissue analyses [21]. The integration of spatial metabolomics techniques, including mass spectrometry imaging, further enables the correlation of metabolite localization with specific cell types, providing critical insights into the compartmentalization of biosynthetic pathways [17] [21].

Artificial intelligence and machine learning are expected to play increasingly prominent roles in multi-omics data integration, with deep neural networks and other AI approaches capable of identifying complex patterns across massive, heterogeneous datasets [16] [18]. These technologies promise to streamline the pathway discovery process by improving gene function prediction, suggesting novel enzyme activities, and even proposing complete biosynthetic routes for uncharacterized metabolites [16]. As these tools mature, they will likely become integrated into user-friendly workflows that make sophisticated multi-omics analyses accessible to a broader range of plant scientists.

For the synthetic biology community, the accelerating pace of pathway discovery through integrated omics presents unprecedented opportunities for engineering sustainable production systems for plant natural products [1] [22]. By providing comprehensive parts lists of biosynthetic genes and regulatory elements, multi-omics approaches enable the rational design of synthetic pathways in optimized plant or microbial chassis [1] [22]. This capabilities alignment between discovery science and engineering applications represents a paradigm shift in how we access and utilize valuable plant-derived compounds, moving from extraction from natural sources to controlled, sustainable production through synthetic biology.

As these technologies converge, the future of plant biosynthetic pathway discovery will be characterized by increasingly integrated workflows that seamlessly combine multi-omics data generation, AI-powered analysis, and high-throughput validation—ultimately democratizing access to nature's chemical diversity and enabling new solutions to challenges in medicine, agriculture, and sustainable manufacturing.

Plant systems are rapidly emerging as robust and scalable platforms for the production of complex biologics and small molecules, offering distinct advantages over traditional microbial and mammalian cell cultures. This technical guide elucidates three core technical strengths—subcellular compartmentalization, eukaryotic post-translational modifications, and unique scalability—that position plant synthetic biology as a transformative force in biomedical and pharmaceutical research. Framed within the context of synthetic biology applications, this review provides drug development professionals with a foundational understanding of the engineering principles, quantitative benchmarks, and experimental protocols that underpin the use of plant chassis for sustainable, high-yield biomanufacturing.

Core Technical Advantages of Plant-Based Systems

The adoption of plant-based expression systems is gaining mainstream advantage for the production of complex biomolecules, from therapeutic proteins to vaccines [23]. While Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells have been the industry workhorse, plant systems offer a compelling alternative with benefits spanning from molecular to manufacturing scales.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Expression Systems

| Feature | Plant-Based Systems | Mammalian (CHO) Systems | Microbial (E. coli) Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Post-Translational Modifications | Eukaryotic; can be humanized; homogeneous glycoforms [23] | Complex eukaryotic; heterogeneous glycoforms [23] | Limited; no complex glycosylation |

| Production Scalability | Highly scalable by increasing plant biomass; lower upstream capital expenditure [23] | Scalable but requires complex bioreactor scale-up; high capital cost [23] | Highly scalable in fermenters |

| Production Time | ~25% faster than conventional bioreactors [23] | Slower due to cell culture and scale-up complexities [23] | Fast |

| Cost Structure | Lower upstream costs; less energy/water intensive [23] | High due to media and infrastructure needs [23] | Low |

| Risk of Contamination | Low risk of adventitious mammalian viruses [23] | High risk, requiring stringent controls | N/A |

| Product Complexity | Can express large, complex proteins (e.g., IgM) [23] | Can express complex proteins | Limited to simpler proteins |

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the core advantages of plant systems and their resulting applications, forming a foundational concept for their use in synthetic biology.

Subcellular Compartmentalization

Functional Role in Metabolic Engineering

Subcellular compartmentalization is a fundamental plant-specific feature that enables the spatial separation of biochemical pathways. Organelles such as vacuoles, plastids, and the endoplasmic reticulum provide distinct biochemical environments that are critical for the biosynthesis of structurally complex metabolites [1]. This sequestration allows for:

- Toxic Intermediate Handling: Isolation of reactive pathway intermediates to prevent cellular damage.

- Optimal Enzyme Activity: Concentrating substrates and enzymes in a specialized environment (e.g., specific pH, co-factors) to enhance catalytic efficiency.

- Pathway Isolation: Preventing crosstalk between endogenous and engineered metabolic pathways.

Case Study: Engineered Compartmentalization of Rho GTPases

Although traditionally viewed as plasma membrane-associated proteins, active pools of Rho GTPases localize to various intracellular compartments, including endomembranes and the nucleus [24]. This localization is critically dependent on Post-Translational Modifications (PTMs) such as prenylation and palmitoylation, which act as trafficking signals [24].

Table 2: Key Post-Translational Modifications Driving Rho GTPase Compartmentalization

| GTPase | Post-Translational Modification | Site | Functional Role in Localization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rac1 | Prenylation | Cys189 | Membrane association [24] |

| Rac1 | Palmitoylation | Cys178 | Reversible membrane anchoring; trafficking to specific membrane microdomains [24] |

| Rac1 | Phosphorylation | Tyr32, Tyr64 | Modulates interaction with regulators/effectors; can influence subcellular localization [24] |

Experimental Protocol: Investigating PTM-Driven Compartmentalization

- Objective: To determine the role of specific PTMs in the subcellular localization of a Rho GTPase.

- Methodology:

- Mutagenesis: Generate point mutants of the Rho GTPase (e.g., Rac1) where key modification residues (e.g., Cys178, Cys189) are substituted (e.g., Cys to Ser).

- Vector Construction: Fuse wild-type and mutant genes with a fluorescent protein tag (e.g., GFP).

- Transient Expression: Introduce constructs into a plant chassis like Nicotiana benthamiana via Agrobacterium-mediated infiltration [1].

- Confocal Microscopy: Image transformed leaf sections after 2-4 days to visualize the subcellular localization of the GFP-tagged proteins.

- Fractionation & Immunoblotting: Confirm localization biochemically by isolating cellular fractions (e.g., plasma membrane, nuclear, cytoplasmic).

Eukaryotic Post-Translational Modifications

Capabilities and Engineering for Human Therapeutics

As eukaryotic cells, plants possess the machinery to perform complex PTMs, with glycosylation being the most critical for therapeutic protein efficacy. A key advantage of plant systems is the tendency to produce a more homogeneous and consistent glycoform pattern compared to the heterogeneity often seen in mammalian cell cultures, which can be affected by culture conditions and scale-up [23].

This platform has been validated by the approval of Medicago's COVIFENZ, a plant-made COVID-19 vaccine, in Canada in 2022 [23]. For monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), plants can deliver a more homogeneous N-linked glycosylation pattern, providing greater assurance that the desired, most efficacious glycoform is represented in the final product [23]. This is particularly valuable for producing afucosylated mAbs for immuno-oncology, which exhibit enhanced potency via greater antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) [23].

Experimental Workflow for Glyco-Engineering

The following diagram outlines a standard workflow for engineering and producing a recombinant therapeutic protein in a plant system, from design to functional validation.

Scalability and Cost-Effectiveness

Quantitative Advantages in Biomanufacturing

The scalability of plant-based systems presents a paradigm shift from traditional bioreactor-based fermentation. Scaling up production is achieved fundamentally by increasing the number of plants, negating the need for the complex and costly scale-up processes required by traditional bioreactor systems [23]. This approach offers significant economic and operational benefits:

- Reduced Capital Expenditure: Upstream capital expenditure for a plant system is estimated to be less than 35% of a traditional staged bioreactor train [23].

- Faster Production Time: The overall production timeline is approximately 25% faster than conventional bioreactor systems [23].

- Operational and Environmental Benefits: Plant systems demonstrate much lower energy consumption, lower water usage (often through recycling), and extremely low waste treatment costs compared to mammalian cell culture [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The advancement of plant synthetic biology relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details essential materials for conducting research in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Plant Synthetic Biology

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Nicotiana benthamiana | A model plant chassis known for rapid biomass, high transgene expression, and efficient Agrobacterium-mediated transformation [1]. | Transient expression of biosynthetic pathways for flavonoids, alkaloids, and vaccine candidates [1]. |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens | A soil bacterium used as a vector to deliver genetic material (T-DNA) into plant cells [1]. | Stable or transient transformation of plant tissues for recombinant protein production. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Systems | Genome editing tools for knock-out, activation, or fine-tuning of endogenous plant genes [1]. | Enhancing functional compound accumulation (e.g., 7- to 15-fold increase in GABA in tomatoes [1]). |

| Integrated Omics Databases | Bioinformatics resources providing genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics data [1]. | Identification and reconstruction of plant natural product biosynthetic pathways. |

| ODAM (Open Data for Access and Mining) | A structured data management approach using spreadsheets to facilitate FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) data compliance [25]. | Managing experimental data tables from multifactorial experiments to improve data consistency and reuse. |

The integrated advantages of subcellular compartmentalization, precise post-translational modifications, and inherently scalable production establish plant systems as a sophisticated and economically viable platform for synthetic biology. For researchers and drug development professionals, leveraging these strengths requires the adoption of integrated workflows that combine omics, genome editing, and robust data management. As the field matures, plant synthetic biology is poised to dramatically expand its role in the sustainable and reliable production of next-generation biotherapeutics, from vaccines and monoclonal antibodies to high-value plant natural products.

Engineering Strategies and Biomedical Applications in Plant Systems

Within the expanding field of plant synthetic biology, the selection of an appropriate host chassis is a foundational decision that profoundly influences the success of research and bioproduction. Plant synthetic biology applies engineering principles to plant systems to design new biological devices or re-engineer existing ones, with transformative applications in sustainable agriculture, biopharmaceutical production, and climate-resilient crop development [1] [26]. This technical guide examines the versatility of Nicotiana benthamiana and other plant platforms, framing their use within the context of synthetic biology applications for plant bioscience research. The chassis serves as the engineered organism that hosts the synthetic genetic constructs, and its inherent characteristics—ranging from metabolic capacity to scalability—determine the efficiency, yield, and complexity of the desired output. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, a comparative understanding of these platforms is critical for strategic experimental design and resource allocation. This document provides an in-depth analysis of current plant chassis systems, with a specific focus on the emergent role of N. benthamiana as a premier biofactory, supported by structured data, detailed protocols, and analytical visualizations to inform chassis selection.

The Rise of Plant-Based Chassis in Synthetic Biology

Traditional metabolic engineering has heavily relied on microbial systems such as Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae for the production of valuable compounds. However, these platforms face significant limitations when applied to the synthesis of plant-derived natural products. These challenges include the toxicity of target compounds to microbial cells, suboptimal metabolic flux, inadequate catalytic efficiency of key enzymes, and an inherent inability to perform complex eukaryotic post-translational modifications essential for the bioactivity of many plant-derived compounds [1] [22]. Furthermore, microbial systems often lack the specialized compartments and biochemical environments required for the biosynthesis of structurally complex plant metabolites [1].

Plant-based chassis are rapidly gaining recognition as vital platforms that naturally accommodate these intricate metabolic networks. They offer several distinct advantages:

- Compartmentalized Metabolism: Plant organelles, particularly chloroplasts, enable the segregation and optimization of enzymatic processes, which is crucial for the biosynthesis of complex secondary metabolites [1].

- Native Biosynthetic Pathways: As the original sources of many high-value natural products, plants possess the innate, and often poorly understood, machinery for their synthesis, reducing the need for extensive pathway reconstruction [27].

- Scalability and Sustainability: Plants are inherently scalable production systems, requiring sunlight and carbon dioxide as primary inputs, making them a cost-effective and sustainable alternative for large-scale biomanufacturing [28] [26].

The field is advanced through the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) framework, which facilitates predictive modeling and systematic enhancement of biosynthetic capabilities. This iterative cycle begins with the multi-omics-guided design of biosynthetic pathways, proceeds to the assembly and introduction of genetic constructs into the chassis, involves rigorous evaluation of output, and concludes with computational analysis to refine subsequent designs [1]. This systematic approach is fundamental to modern plant synthetic biology.

3Nicotiana benthamianaas a Versatile Model Chassis

Among plant-based platforms, Nicotiana benthamiana has emerged as a preeminent model organism and workhorse for plant synthetic biology and molecular farming. Its prominence is attributed to a confluence of biological and practical traits that make it exceptionally amenable to genetic manipulation and high-yield production.

Key Characteristics and Advantages

- High Susceptibility to Pathogens: N. benthamiana possesses a natural mutation in its RNA-dependent RNA polymerase gene (Rdr1), which impairs its RNA silencing-based antiviral defense mechanism. This "genomic accommodation" makes the plant highly susceptible to a wide array of pathogens, including viruses and Agrobacterium, resulting in high levels of transgene expression [29].

- Rapid Biomass Accumulation: The plant grows quickly and produces substantial leaf biomass, which is the primary tissue for agroinfiltration and recombinant protein production [1].

- Efficient Transient Expression System: The most significant advantage of N. benthamiana is its compatibility with Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression (agroinfiltration). This technique allows for the rapid, high-yield production of recombinant proteins and metabolites within days, bypassing the time-consuming process of generating stable transgenic plants [1] [29]. Yields can reach up to 5 grams of recombinant protein per kilogram of fresh leaf biomass [29].

- Proven Regulatory Success: The platform's credibility is solidified by the approval of Covifenz, a plant-based COVID-19 vaccine produced in N. benthamiana by Medicago Inc., which met Health Canada's safety, efficacy, and quality standards [29].

Proteomic Insights into Host-Pathogen Interactions

A comparative proteomic study of N. benthamiana infected with Chinese wheat mosaic virus (CWMV) provided a systems-level understanding of the plant's response to pathogen challenge. The analysis identified 390 differentially expressed proteins (DEPs), with a significant majority (218 DEPs) localized to the chloroplast. This finding indicates that viral infection profoundly disrupts chloroplast function and, consequently, the synthesis of abscisic acid (ABA), a key plant hormone. Further investigation confirmed that the ABA signaling pathway was suppressed during CWMV infection and that exogenous ABA application could induce host defenses against the virus [30]. This deep understanding of host factors is invaluable for designing synthetic circuits that can modulate plant responses for enhanced bioproduction.

Comparative Analysis of Plant Chassis Platforms

The selection of a host chassis extends beyond N. benthamiana to include other plant systems, each with unique strengths and optimal application spaces. The following table provides a structured comparison of key plant-based platforms.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Plant Chassis Platforms for Synthetic Biology

| Chassis Platform | Key Features & Advantages | Primary Applications | Expression Yield & Timeline | Notable Case Studies/Products |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nicotiana benthamiana (Transient) | High susceptibility to pathogens; Rapid biomass; Efficient agroinfiltration; Scalable transient system [1] [29] | Recombinant proteins, vaccines, monoclonal antibodies, metabolic engineering of natural products [1] [29] | High yield (up to 5 g/kg biomass); Very fast (3-7 days post-infiltration) [29] | Covifenz (COVID-19 vaccine); ZMapp (Ebola therapeutic); Various flavonoid and alkaloid pathways [1] [29] |

| Plant Cell Suspension Cultures (e.g., N. tabacum BY-2) | Controlled, sterile bioreactor environment; Homogeneous cell population; Consistent yields [31] | Recombinant protein production; Functional genomics screening; Prototyping genetic circuits [31] | Consistent yields; Expression strength correlates well with whole-plant systems [31] | Used for systematic comparison of promoters/terminators; ELELYSO (taliglucerase alfa) produced in carrot cell culture [29] [31] |

| Stable Transgenic Crops (e.g., Rice, Maize) | Stable, heritable transgene integration; Tissue-specific expression (e.g., endosperm); Long-term, large-scale production potential [32] | Nutritional enhancement (nutraceuticals); Production of storage-stable proteins; Sustainable biomolecule manufacturing [32] | Requires months to years to generate stable lines; High volume production once established | Golden Rice (carotenoids); Purple Rice (anthocyanins) using endosperm-specific promoters [32] |

| Microbial Systems (e.g., E. coli, S. cerevisiae, P. pastoris) | Well-characterized genetics; High growth rates; Established industrial fermentation [1] [28] | Simple plant natural products; Pathway prototyping; Molecules not requiring complex modification [1] [22] | High titers for compatible compounds; Fast microbial growth (hours) | Table-top microfluidic reactors for on-demand therapeutic production (e.g., rHGH, IFNα2b) [28] |

Quantitative Performance Data for Nicotiana Expression Systems

The performance of a chassis is critically dependent on the genetic parts used to construct expression vectors. Systematic comparisons of promoters and terminators in Nicotiana systems provide quantitative data essential for rational design.

Table 2: Performance of Genetic Parts in Nicotiana Expression Systems [31]

| Promoter/Terminator Combination | Relative Expression Strength (EGFP Fluorescence) | Key Findings and Implications |

|---|---|---|

| CaMV 35S Promoter | Baseline (High) | Considered a workhorse promoter; strong constitutive expression but can lead to silencing [31]. |

| Various Novel/Synthetic Promoters | Varied by >2 orders of magnitude | Demonstrates the vast design space for tuning gene expression levels [31]. |

| Effect of Terminator Selection | Modulation of up to 5-fold in mRNA accumulation | Terminator choice is as critical as promoter selection for determining final protein yield [31]. |

| Promoter-Terminator Synergy | Non-additive effects on expression | Specific promoter-terminator pairs can interact to produce synergistic boosts in output [31]. |

| Gene Dosage Effects | Non-linear correlation with expression level | Simply increasing the number of gene copies does not guarantee a proportional increase in yield [31]. |

Essential Tools and Reagents for Plant Synthetic Biology

The engineering of plant chassis relies on a sophisticated toolkit of molecular parts and technologies to achieve precise and robust control of gene expression.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Plant Chassis Engineering

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function and Mechanism | Application in Chassis Engineering |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Promoters [32] [31] | DNA sequences upstream of a gene that drive defined expression patterns (constitutive, tissue-specific, inducible). Composed of core, proximal, and distal cis-regulatory elements. | Used to control the timing, tissue location, and strength of transgene expression, minimizing metabolic burden and unwanted side effects. |

| Viral Vectors (e.g., MagnICON, pEAQ) [29] | Deconstructed viral vectors engineered for high-level, systemic expression of transgenes while addressing biosafety concerns of full viruses. | Enables extremely high-yield production of recombinant proteins and metabolites in N. benthamiana via agroinfiltration. |

| CRISPR/Cas Systems [1] | Genome editing technology that uses a guide RNA and Cas nuclease to create targeted double-strand breaks in the host genome, enabling gene knock-outs, knock-ins, and regulation. | Used for precision engineering of host metabolic pathways, knocking out competing pathways, or inserting entire biosynthetic gene clusters. |

| Bidirectional Promoters [32] | An intergenic DNA sequence that drives the simultaneous expression of two genes located on opposite strands. | Allows for the coordinated expression of multiple genes (gene pyramiding) from a single genetic locus, avoiding transcriptional gene silencing from repeated promoter use. |

| Morphogenic Regulators (e.g., Baby Boom, Wuschel2) [32] | Transcription factors that promote plant cell totipotency and regeneration. | Driven by tissue-specific or inducible promoters to drastically improve transformation efficiency of recalcitrant plant species, overcoming a major bottleneck. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Agroinfiltration of N. benthamiana

The following methodology details the standard procedure for transient gene expression in N. benthamiana using agroinfiltration, a cornerstone technique for rapid biomolecule production [1] [29].

The agroinfiltration process for transient expression in N. benthamiana is visualized in the following workflow, from vector design to final analysis.

Step-by-Step Methodology

Vector Construction and Agrobacterium Transformation

- Design and Build: The gene of interest (GOI), often codon-optimized for plants, is cloned into a T-DNA binary vector. This vector should contain a suitable plant promoter (e.g., CaMV 35S or a stronger synthetic variant) and terminator. For metabolic engineering, multiple genes may be assembled in a single operon or on separate vectors for co-infiltration [1] [32].

- Transformation: The constructed plasmid is introduced into a disarmed strain of Agrobacterium tumefaciens (e.g., GV3101) via electroporation or freeze-thaw transformation. Positive clones are selected on appropriate antibiotics.

Agrobacterium Culture Preparation

- Primary Culture: A single transformed colony is used to inoculate a small volume (e.g., 5-10 mL) of LB medium with the requisite antibiotics and grown for ~24-48 hours at 28°C with shaking.

- Secondary Culture: The primary culture is diluted 1:50 to 1:100 into a larger volume of fresh, induction medium (e.g., LB with antibiotics, 10 mM MES buffer, and 20 μM acetosyringone). Acetosyringone is a phenolic compound that activates the Agrobacterium virulence (vir) genes, essential for T-DNA transfer.

- Harvesting: The secondary culture is grown to an OD600 of 0.5-1.0. The bacterial cells are then pelleted by centrifugation and resuspended in an infiltration buffer (e.g., 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM MES, 150 μM acetosyringone). The final OD600 is adjusted to a predetermined optimal density, typically between 0.2 and 1.0, which may require optimization for different constructs.

Plant Infiltration and Incubation

- Plant Material: Healthy 4-6 week old N. benthamiana plants are used. The plants should be well-watered before infiltration to maintain turgor pressure.

- Infiltration: The bacterial suspension is drawn into a syringe without a needle. The syringe is pressed firmly against the abaxial (lower) side of a leaf, while supporting the adaxial (upper) side with a finger. Gentle pressure is applied to infiltrate the suspension, causing a water-soaked appearance in the leaf area. Alternatively, for high-throughput or whole-plant applications, vacuum infiltration can be employed [29].