Protoplast vs. Nuclei Isolation for scRNA-seq: A Comprehensive Guide to Methods, Applications, and Optimization

This article provides a detailed guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical sample preparation techniques of protoplast and nuclei isolation for single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq).

Protoplast vs. Nuclei Isolation for scRNA-seq: A Comprehensive Guide to Methods, Applications, and Optimization

Abstract

This article provides a detailed guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical sample preparation techniques of protoplast and nuclei isolation for single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq). It covers the foundational principles of how these methods enable cellular heterogeneity analysis in plants and animals, respectively. The content delivers step-by-step methodological protocols, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and offers a direct comparative analysis to guide method selection for specific research goals, such as functional genomics in crops or cancer biology in humans. By synthesizing the latest advancements, this resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to generate high-quality single-cell data and accelerate discoveries in biomedicine and agriculture.

Why Sample Prep Matters: Unlocking Cellular Heterogeneity with Protoplast and Nuclei Isolation

The revolutionary power of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) to unravel cellular heterogeneity, discover novel cell types, and map developmental trajectories is fundamentally constrained by a critical initial step: the efficient and unbiased isolation of single cells or nuclei from complex tissues [1]. This process of tissue dissociation presents a universal challenge across biological research, as the quality of the resulting single-cell suspension directly dictates the resolution, accuracy, and reliability of all subsequent genomic data [2]. In plant systems, this challenge is compounded by the presence of a rigid cell wall, necessitating specialized approaches such as protoplast isolation or nuclei extraction to access the transcriptome [3] [4]. The choice between these two primary paths is not trivial; it represents a significant methodological branch point with profound implications for experimental outcomes. Protoplast isolation, which involves the enzymatic removal of the cell wall, can inadvertently induce wounding responses and transcriptional stress artifacts, potentially confounding biological interpretations [4] [5]. Conversely, single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) bypasses the need for cell wall digestion by using isolated nuclei, thereby preserving the native state of many fragile cell types and enabling the use of frozen or archived tissues [4] [6]. This Application Note delineates detailed, optimized protocols for both routes, providing researchers with the tools to navigate the core challenge of sample preparation for high-fidelity single-cell transcriptomics.

Methodological Approaches: Protoplast vs. Nuclei Isolation

Protoplast Isolation for Plant scRNA-seq

The isolation of protoplasts is a gateway to scRNA-seq for many plant species. A robust protocol, exemplified by work in cotton and Chirita pumila, hinges on precise enzymatic digestion and gentle handling to maximize yield and viability [7] [8].

Detailed Protocol for Cotton Root Protoplast Isolation [7]:

- Plant Material & Growth: Surface-sterilize cotton seeds (Gossypium hirsutum cv. ND601) and germinate on moist towels at 25°C for ~36 hours. Transfer seedlings with radicles ~1 cm long to a hydroponic system. Critical Tip: Use taproots from plants grown in hydroponics for 65-75 hours after germination for optimal results. Culture for less than 48 hours or more than 96 hours significantly reduces yield and quality.

- Tissue Preparation: Collect taproots from 25-50 seedlings. Using a sharp razor blade, cut roots into 0.5-1 mm thick translucent slices. Keep tissue immersed in solution to prevent desiccation.

- Enzymatic Digestion: Immerse tissue slices in 10 mL of freshly prepared enzyme solution. The solution consists of 1.5% (w/v) Cellulase R10, 0.75% (w/v) Macerozyme R10, 0.4 M mannitol, 20 mM KCl, 20 mM MES (pH 5.7), 10 mM CaCl2, and 0.1% BSA. Filter-sterilize before use.

- Incubation: Digest the tissue for 3 hours with gentle shaking (40-50 rpm) at 25°C in the dark. Monitor protoplast release microscopically.

- Protoplast Release & Filtration: Add an equal volume of W5 solution (154 mM NaCl, 125 mM CaCl2, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM MES pH 5.7) to the enzyme mixture and shake vigorously for 10 seconds. Filter the suspension sequentially through four layers of Miracloth and a pre-moistened 40 μm cell strainer into a round-bottomed tube. For scRNA-seq, a 30 μm strainer may be necessary to exclude larger cells.

- Purification & Storage: Centrifuge the filtrate at 100 x g for 5 minutes at 25°C using a swinging-bucket rotor with soft acceleration/deceleration settings. Gently discard the supernatant and resuspend the pellet in 5 mL of pre-chilled W5 solution. Keep the protoplast suspension on ice for 30-60 minutes before proceeding to counting, transfection, or scRNA-seq library preparation.

This protocol reliably yields up to 3.55 x 10^5 protoplasts per gram of tissue with a viability exceeding 93% [7]. A universal two-step digestion protocol developed for Chirita pumila further enhances viability (92.97%) and is applicable across diverse angiosperm organs [8].

Single-Nuclei Isolation for snRNA-seq

For tissues that are recalcitrant to protoplasting, prone to dissociation-induced stress, or uniquely archived, snRNA-seq offers a powerful alternative. The following protocol, adapted from human and plant studies, provides a general framework for nuclei isolation [9] [6].

Detailed Protocol for Single-Nuclei Isolation [9] [6]:

- Sample Preparation & QC (Basic Protocol 1 [6]): For frozen tissues, retrieve the sample on dry ice. Cut a small piece (e.g., ~5x5x5 mm) of the tissue of interest for RNA quality control. Isolate RNA and determine the RNA Integrity Number (RIN). A RIN of ≥5 is recommended to proceed with nuclei isolation, as it indicates sufficient RNA quality for downstream transcriptomics.

- Tissue Lysis/Homogenization: On ice, mince the main tissue sample to 0.5-1 mm pieces with a sterile scalpel. Transfer the pieces to a tube containing 1 mL of cold Lysis Buffer (1X PBS, 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 0.0125% Triton X-100, 1 mM DTT, 0.2 U/μL RNase inhibitor). Critical Tip: Freshly prepare all reagents and keep them ice-cold. Decontaminate surfaces and treat equipment with RNase inhibitor to prevent RNA degradation.

- Mechanical Disruption: Place the tube on a magnetic stir plate with a micro stir-rod and incubate for 5 minutes at 100 RPM on ice. For tougher tissues, a mechanical homogenizer like a TissueLyser II may be required [6].

- Nuclei Recovery: Allow large debris to settle, then transfer the supernatant to a 15 mL tube containing 6 mL of cold Wash & Resuspension Buffer (1X PBS, 2% BSA, 0.2 U/μL RNase inhibitor). Repeat the lysis and wash steps 2-3 times to maximize nuclei yield.

- Purification & Filtration: Centrifuge the pooled supernatant at 600 x g for 5 minutes at 4°C. Gently resuspend the pellet in 1 mL of Wash Buffer and filter the suspension sequentially through 70 μm and 40 μm flow cytometer-compatible strainers.

- Quality Control: Centrifuge the filtered effluent again at 600 x g for 5 minutes and resuspend the final pellet in ~200 μL of Wash Buffer. Quantify nuclei using a hemocytometer or automated cell counter with DAPI staining. Assess nuclei integrity and the absence of contaminating cellular debris by microscopy.

This protocol is effective for obtaining intact nuclei with normal morphology and is compatible with a range of tissues, including clinical biopsies and various plant organs [9] [5].

Comparative Analysis: Protoplasts vs. Nuclei

Table 1: A comparative summary of protoplast-based scRNA-seq and nucleus-based snRNA-seq.

| Feature | Protoplast-based scRNA-seq | Nucleus-based snRNA-seq |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Material | Fresh, living tissue [3] | Fresh or frozen tissue [4] [6] |

| Key Challenge | Enzymatic digestion of cell wall; stress responses [4] [5] | Mechanical homogenization; RNA degradation [9] |

| Transcript Coverage | Whole-cell transcriptome (cytoplasmic + nuclear) [1] | Primarily nuclear transcriptome [4] |

| Cell Type Representation | May be biased against cell types with tough walls [4] | Broader representation, including large or fragile cells [6] |

| Typical Yield | High (e.g., 3.55 x 10^5/g in cotton roots) [7] | Variable, dependent on tissue and protocol [9] |

| Typical Viability | High (>90% with optimization) [7] [8] | Not applicable (assessed via nuclei integrity) |

| Best Suited For | Functional studies requiring living cells, transient expression [7] [8] | Complex, frozen, or difficult-to-dissociate tissues; archival samples [4] [5] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Success in single-cell and single-nuclei workflows depends on a carefully selected set of reagents and tools. The following table lists key components for establishing these protocols.

Table 2: Key research reagent solutions and their applications in protoplast and nuclei isolation.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|

| Cellulase R10 / Macerozyme R10 | Enzymatic hydrolysis of cellulose and pectin in plant cell walls. | Protoplast isolation from cotton roots and Chirita pumila leaves [7] [8]. |

| Mannitol | Osmoticum to maintain pressure and prevent protoplast lysis. | Component of enzyme solution and washing buffers [7]. |

| Triton X-100 | Mild detergent for permeabilizing cell membranes to release nuclei. | Component of lysis buffer for nuclei isolation [9]. |

| RNase Inhibitor | Protects RNA from degradation during isolation procedures. | Essential addition to lysis and wash buffers for nuclei isolation [9]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Facilitates plasmid DNA uptake into protoplasts for transfection. | PEG-CaCl2 mediated transformation in transient expression assays [8]. |

| DAPI (4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) | Fluorescent DNA stain for quantifying and assessing nuclei. | Staining for nuclei counting and viability assessment [9]. |

| FlowMi Cell Strainers (40 μm, 70 μm) | Removal of aggregates and large debris from nuclei suspensions. | Sequential filtration to purify single nuclei [9]. |

Workflow and Decision Framework

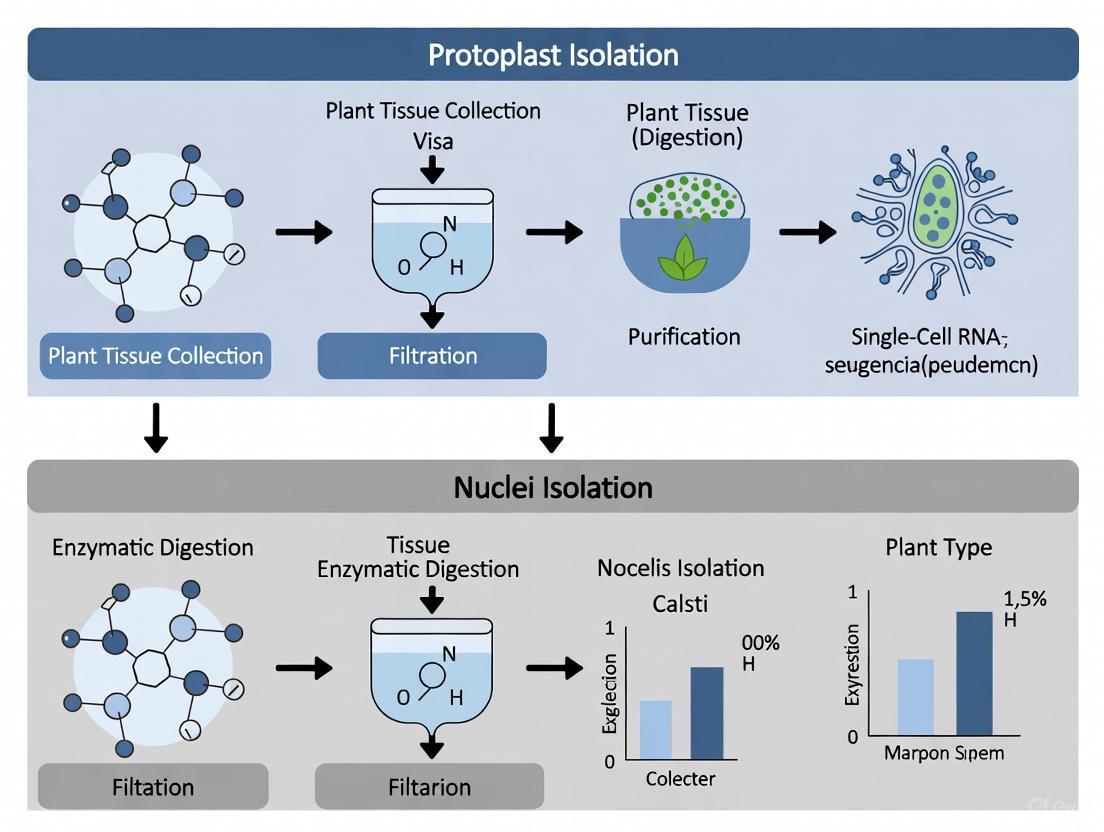

The decision to use protoplasts or nuclei for single-cell transcriptomics is multifaceted, depending on biological questions, sample availability, and technical constraints. The following workflow diagram maps this critical decision path and the subsequent experimental steps.

The journey from complex tissue to a high-quality single-cell suspension is the foundational step upon which the entire edifice of scRNA-seq is built. As this Application Note demonstrates, researchers are equipped with two powerful, complementary strategies: protoplast isolation and nuclei isolation. The choice between them should be guided by a careful consideration of the biological system, the experimental goals, and the practical constraints of sample availability. By adhering to the optimized protocols and decision framework outlined herein, scientists can reliably overcome the core challenge of sample preparation. This ensures that the resulting single-cell data truly reflects the underlying biology, free from the artifacts of preparation, thereby unlocking the full potential of single-cell transcriptomics to illuminate cellular heterogeneity and function in health, disease, and development.

Protoplasts, plant cells that have had their cell walls removed, serve as a fundamental resource in plant biotechnology and functional genomics. They provide a unique single-cell system ideal for a variety of applications, including transient gene expression, transformation, and the study of cellular processes. In the context of transcriptomics, protoplasts offer a pathway to single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), enabling the resolution of cellular heterogeneity within complex plant tissues. However, the process of protoplast isolation induces rapid and significant transcriptional shifts, which can confound the analysis of native gene expression states. This application note details standardized protocols for protoplast isolation and introduces the alternative of single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) for more accurate transcriptomic profiling, providing researchers with critical methodologies for accessing plant cellular transcriptomes.

Key Methodological Approaches for Transcriptomic Access

For transcriptomic studies, the choice between using protoplasts or isolated nuclei is critical. The table below summarizes the core characteristics of these two main approaches.

Table 1: Comparison of Transcriptomic Access Methods Using Protoplasts or Nuclei

| Feature | Protoplast-based scRNA-seq | Nuclei-based snRNA-seq |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Unit | Whole, living cell | Isolated nucleus |

| Transcriptomic Scope | Cytoplasmic & nuclear RNA | Primarily nuclear RNA |

| Tissue Starting State | Typically fresh tissue | Fresh or cryopreserved tissue [10] |

| Key Technical Challenge | Enzymatic cell wall digestion inducing stress responses | Mechanical homogenization to preserve nuclear integrity |

| Major Artifact Source | Transcriptional changes induced by prolonged enzymatic digestion [5] | Loss of cytoplasmic transcripts, ambient RNA |

| Ideal Application | Studies of cellular processes not affected by isolation stress | Profiling of complex tissues, archived samples, and immune responses [5] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Protoplast Isolation

Successful protoplast isolation relies on a specific set of reagents. The following table lists key solutions and their functions in the protocol.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Protoplast Isolation

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Enzyme Mixture (Cellulase, Macerozyme) | Digests cellulose and pectin in the plant cell wall [11] [12] [13] to release protoplasts. |

| Osmoticum (Mannitol or Sorbitol) | Maintains osmotic balance to prevent the fragile protoplasts from bursting [12]. |

| Plasmolysis Buffer | Often contains mannitol; initiates pre-plasmolysis of plant cells before enzymatic digestion, enhancing yield [11] [14]. |

| W5 Solution (or similar washing buffer) | Used for washing and purifying protoplasts after digestion; contains salts to maintain viability [11] [15] [13]. |

| MMg Solution | Contains mannitol and magnesium; used for resuspending protoplasts prior to transfection [15]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Facilitates the delivery of DNA, RNA, or proteins (e.g., CRISPR/Cas9 RNP) into protoplasts [12] [14] [13]. |

Optimized Protocol for Mesophyll Protoplast Isolation

This protocol is adapted from established methods for leaf tissues from multiple species, including grapevine, pea, and Brassica carinata [11] [15] [13].

Materials and Reagents

- Plant Material: Young, fully expanded leaves from 3- to 4-week-old plants are optimal [11] [13]. For grapevine, 40 mg of young leaves is recommended [15].

- Enzyme Solution: Filter-sterilized solution containing:

- W5 Solution: 154 mM NaCl, 125 mM CaCl₂, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM MES, pH 5.7 [11] [13].

- Plasmolysis Solution: 0.4 M mannitol [11].

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Plant Growth and Leaf Preparation: Grow plants under controlled conditions. Excise young leaves and remove the midrib. Cut leaf tissue into thin strips (0.5–1.0 mm) using a sharp razor blade. The "strip-cutting" method is superior to random cutting for yield [15].

- Plasmolysis: Transfer the sliced tissue into a Petri dish containing Plasmolysis Solution. Incubate for 30 minutes in the dark at room temperature.

- Enzymatic Digestion: Replace the plasmolysis solution with the pre-cooled Enzyme Solution. Use approximately 10 mL of enzyme solution per gram of leaf tissue. Incubate in the dark for 6–16 hours at 23–25°C with gentle shaking (30–40 rpm).

- Protoplast Release and Purification:

- Gently swirl the digestion mixture to release the protoplasts.

- Add an equal volume of W5 solution to stop the enzymatic reaction.

- Filter the suspension through a 40-100 μm nylon mesh to remove undigested debris [11] [15].

- Transfer the filtrate to a centrifuge tube and spin at 100 × g for 5–10 minutes.

- Carefully remove the supernatant. Resuspend the pellet (protoplasts) in W5 solution.

- Repeat the washing step twice.

- Viability and Yield Assessment: Resuspend the final protoplast pellet in an appropriate volume of W5 or MMg solution. Determine protoplast density using a hemocytometer. Assess viability via staining (e.g., Fluorescein Diacetate, FDA) or by observing cytoplasmic streaming [14]. Yields can vary from 75 × 10⁶ protoplasts/g tissue in grapevine [15] to transfection efficiencies of up to 59% in pea [13].

An Alternative Pathway: Single-Nucleus RNA Sequencing (snRNA-seq)

To circumvent the transcriptional artifacts of protoplasting, snRNA-seq uses isolated nuclei. The workflow diagram below outlines the key steps for this method.

snRNA-seq Protocol for Cryopreserved Tissues

This protocol is adapted from a method demonstrating effective nuclei extraction from low-input (15 mg) cryopreserved human tissues, a approach that is directly transferable to plant research [10].

- Tissue Homogenization: Mince 15-30 mg of cryopreserved tissue on dry ice. Transfer to ice-cold lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl₂, 0.05% NP-40). For plant tissues, the buffer may require optimization.

- Dounce Homogenization: Use a loose (A) and/or tight (B) Dounce homogenizer. The number of strokes (e.g., 10-20 strokes) must be empirically determined for each tissue type to balance nuclei yield and integrity [10] [16].

- Nuclei Purification: Filter the homogenate through a 30 μm strainer. Layer the filtrate over a 29% iodixanol cushion and centrifuge at 1000 × g for 10-20 minutes at 4°C. This step effectively pellets nuclei while separating them from cellular debris [10].

- Nuclei Sorting and QC: Resuspend the pellet in a nuclei washing buffer containing RNAse inhibitor. Stain nuclei with a viability dye like 7-AAD and sort using Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) to select for intact, high-quality nuclei [10]. Confirm integrity and concentration by microscopy before proceeding to library construction.

Both protoplast isolation and nuclei isolation provide viable paths to transcriptomic access in plants. The choice of method hinges on the specific research question. Protoplasts are excellent for functional assays and transient transformation, but their use in scRNA-seq is compromised by isolation-induced stress responses. For high-fidelity transcriptomic mapping of complex plant tissues, especially when using cryopreserved samples or studying rapid responses like immunity, snRNA-seq from isolated nuclei offers a robust and artifact-minimized alternative. By applying the detailed protocols and considerations outlined in this document, researchers can make an informed choice and successfully implement these techniques in their investigations.

Single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) has emerged as a powerful alternative to single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), particularly when working with complex, tough, or cryopreserved tissues that pose significant challenges for traditional protoplast isolation methods. While scRNA-seq provides unprecedented insights into cellular heterogeneity, its application is limited by requirements for fresh tissues and the technical challenges of dissociating certain cell types without introducing artifacts. Nuclei isolation overcomes these limitations by enabling transcriptomic profiling of tissues that are difficult to dissociate, including frozen clinical samples, formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) archives, and complex organs like brain and adipose tissue [10] [17] [18].

The fundamental advantage of snRNA-seq lies in its compatibility with preserved tissues and its ability to minimize dissociation-induced transcriptional stress responses. Unlike whole-cell approaches that require immediate processing of fresh samples, nuclei can be isolated from tissues stored in biobanks, thereby unlocking vast repositories of clinical specimens for transcriptomic analysis [10]. This technical advancement is particularly valuable for studying human diseases, developmental processes, and cellular responses in contexts where fresh tissue procurement is impractical or impossible. Furthermore, snRNA-seq enables the profiling of cell types that are notoriously difficult to isolate intact, including neurons, adipocytes, and cardiomyocytes, thus providing a more comprehensive view of tissue heterogeneity [18].

Core Principles: Advantages of Nuclei Over Whole Cells

Technical and Biological Rationale

The transition from single-cell to single-nucleus RNA sequencing is motivated by several technical and biological considerations. First, nuclei maintain transcriptional profiles that closely correlate with those of whole cells, making them reliable proxies for cellular states [10]. Second, the nuclear membrane provides a protective barrier that preserves RNA integrity during the isolation process, reducing degradation artifacts that can compromise data quality. Third, nuclei are more resistant to mechanical stress than whole cells, allowing for more vigorous processing methods that ensure representative sampling of all cell types within a tissue [19].

Perhaps the most significant advantage of snRNA-seq is its compatibility with frozen and fixed specimens. Clinical samples are often cryopreserved or formalin-fixed to preserve morphology for pathological assessment, rendering them unsuitable for standard scRNA-seq protocols. snRNA-seq successfully bridges this gap, enabling transcriptomic analysis of samples that would otherwise be inaccessible for single-cell studies [10] [17]. This compatibility has profound implications for biomedical research, as it facilitates the analysis of well-annotated clinical cohorts with extensive follow-up data, thereby strengthening correlations between transcriptional signatures and clinical outcomes.

Applications Across Challenging Tissue Types

- Cryopreserved tissues: Enables analysis of rare clinical specimens with just 15 mg input material [10]

- FFPE archives: Unlocks decades of preserved clinical samples for transcriptomic studies [17]

- Complex organs: Maintains cellular diversity in brain, adipose, and other heterogeneous tissues [19] [18]

- Delicate cell types: Preserves transcriptional profiles of neurons, adipocytes, and other fragile cells [18]

Established Protocols and Methodologies

Versatile Low-Input Protocol for Cryopreserved Tissues

Principle: This method enables robust nuclei isolation from minimal amounts (15 mg) of cryopreserved human tissues, making it particularly valuable for rare clinical specimens [10].

Protocol Steps:

- Tissue Preparation: Cryopreserved samples are minced in a pre-cooled mortar on dry ice using a scalpel, then transferred to 15 mL tubes.

- Homogenization: Add 3 mL of ice-cold lysis buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl₂·6H₂O, 0.05% NP-40). Homogenize using a Dounce homogenizer with pestle selection (loose or tight) and stroke numbers optimized for specific tissues.

- Lysis Control: Incubate on ice for 5 minutes, then stop the reaction with 5 mL of ice-cold nuclei washing buffer (0.5X PBS, 5% BSA, 0.25% Glycerol, 40 units/mL Protector RNAse inhibitor).

- Filtration and Purification: Filter through 30 µm MACS strainers, then centrifuge for 10 minutes at 1000 g (4°C).

- Density Gradient: Resuspend pellets in nuclei washing buffer, then add 1 mL of 50% (wt/vol) iodixanol. Gently layer on top of 2 mL cushion of 29% (wt/vol) iodixanol.

- Nuclei Sorting: Stain with 7-AAD for 10 minutes, then sort using a BD FACSAria Fusion with 70 µm nozzle to collect intact nuclei [10].

Tissue-Specific Optimization:

- Brain tissue: Use pestle B (tight clearance) with 15 strokes

- Bladder tissue: Use pestle A (loose clearance) with 10 strokes

- Lung tissue: Use pestle B with 20 strokes

- Prostate tissue: Use pestle A with 15 strokes

snCED-seq: Advanced Method for FFPE Tissues

Principle: The Cryogenic Enzymatic Dissociation (CED) strategy enables high-yield nuclei extraction from FFPE samples by addressing the challenges of RNA cross-linking while preserving RNA integrity [17].

Protocol Steps:

- Deparaffinization: Hydrate FFPE sections using standard histology protocols.

- Protein Digestion: Incubate with proteinase K (optimized concentration) at low temperature (4°C) instead of conventional high-temperature incubation.

- Surfactant Treatment: Use sarcosyl as an anionic surfactant instead of SDS or Triton X-100 for better nuclear membrane preservation.

- Nuclei Release: Gentle mechanical agitation in cryogenic conditions to release nuclei without filtration or ultracentrifugation.

- Quality Assessment: Verify nuclei integrity and count using epifluorescence microscopy [17].

Key Advantages:

- 10x increase in nuclei yield compared to conventional methods

- Significant reduction in hands-on time

- Minimal secondary RNA degradation

- Preservation of intranuclear transcripts

- Enhanced gene detection sensitivity with lower mitochondrial and ribosomal contamination

Robust Protocol for RNA Quality Preservation

Principle: This method addresses tissue-specific variations in RNase activity that can compromise nuclear RNA quality, particularly in challenging tissues like adipose tissue [18].

Protocol Steps:

- RNase Inhibition: Incorporate vanadyl ribonucleoside complex (VRC) during nucleus isolation to maintain RNA quality across diverse tissue types.

- Tissue Homogenization: Process tissues in chilled homogenization buffer containing VRC and recombinant RNase inhibitors.

- Nuclei Purification: Centrifuge through appropriate density medium to separate intact nuclei from debris.

- Quality Control: Assess RNA integrity and nucleus morphology before proceeding to library preparation [18].

Performance: This optimized protocol successfully maintains nuclear RNA integrity in all tested tissues except pancreas and spleen, with well-dispersed nucleus populations without clumps. Nuclear RNA remains intact for up to 24 hours when stored at 4°C, significantly outperforming standard protocols where severe degradation occurs within 2 hours [18].

Comparative Analysis of Isolation Methods

Method Performance Across Tissue Types

Table 1: Comparison of Nuclei Isolation Methods and Their Applications

| Method | Input Requirements | Key Advantages | Tissue Compatibility | Nuclei Yield | RNA Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Input Cryopreserved [10] | 15 mg cryopreserved tissue | Minimal input requirement, FACS sorting | Brain, bladder, lung, prostate | 1,550-7,468 nuclei per sample | High (comparable to fresh tissues) |

| snCED-seq [17] | Single 50 μm FFPE section | 10x higher yield, works with FFPE archives | Brain, liver, kidney, spleen, intestines | >1 million nuclei per gram tissue | Enhanced gene detection sensitivity |

| Sucrose Gradient Centrifugation [19] | ~30 mg fresh/frozen tissue | Well-established, cost-effective | Brain cortex | ~60,000 nuclei per mg input | Defined individual nuclei, minimal debris |

| Machine-Assisted Platform [19] | ~30 mg fresh/frozen tissue | Automated, minimal variability | Brain cortex | ~60,000 nuclei per mg input | Well-separated, intact nuclei (99% integrity) |

| Spin Column-Based [19] | ~30 mg fresh/frozen tissue | Fast processing, no special equipment | Brain cortex | 25% fewer nuclei than other methods | Aggregation and substantial debris |

Tissue-Specific Considerations and Challenges

Table 2: Tissue-Specific Optimization Requirements for Quality Nuclei Isolation

| Tissue Type | Key Challenges | Recommended Methods | Optimal Yield Indicators | Quality Control Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain [19] | Cellular heterogeneity, neuronal fragility | Sucrose gradient centrifugation, Machine-assisted platform | 2 million nuclei from 30 mg input | 85-99% nuclei integrity, minimal debris |

| Adipose [18] | High RNase activity, lipid content | VRC-optimized protocol | Varies by depot | RNA integrity number >7, smooth nuclear membranes |

| FFPE Archives [17] | RNA cross-linking, fragmentation | snCED-seq (cryogenic enzymatic dissociation) | >100,000 nuclei per gram tissue | Size distribution 6-8 μm, intact morphology |

| Multiple Organs [17] | Variable biophysical properties | CED method with parameter adjustment | Millions of nuclei for spleen, intestines, kidney | Independent, intact, unaggregated nuclei |

| Plant Roots [5] | Cell wall rigidity, protoplasting artifacts | Protoplasting-free snRNA-seq | 52,706 nuclei from 12-day roots | Median 1001 genes and 1348 UMI per nucleus |

Essential Reagents and Equipment

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Equipment for Quality Nuclei Isolation

| Reagent/Equipment | Function/Purpose | Specific Examples/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| Dounce Homogenizer [10] | Tissue disruption with controlled mechanical force | Pestle A (loose clearance: 0.0025-0.0055 inches) for delicate tissues; Pestle B (tight clearance: 0.0005-0.0025 inches) for tough tissues |

| RNase Inhibitors [10] [18] | Prevention of RNA degradation during isolation | Protector RNase Inhibitor (40 U/mL); Vanadyl Ribonucleoside Complex (VRC) for challenging tissues; Recombinant RNase Inhibitors |

| Density Gradient Media [10] | Purification of intact nuclei from debris | Iodixanol (29-50% wt/vol); Sucrose cushion solutions |

| Sorting Platform [10] | Enrichment of high-quality nuclei | BD FACSAria Fusion with 70 µm nozzle; 7-AAD viability staining; Size calibration beads (7.88, 10.1, 16.4 µM) |

| Protease Enzymes [17] | Digestion of cross-linked proteins in FFPE samples | Proteinase K (optimized concentration for CED method); Sarcosyl surfactant for nuclear membrane preservation |

| Filtration Systems [10] | Removal of tissue debris and aggregates | 30 µm MACS strainers; Customized filtration based on tissue type |

| Buffer Systems [10] [18] | Maintenance of nuclear integrity and RNA stability | Lysis buffer (Tris-HCl, NaCl, MgCl₂, NP-40); Nuclei washing buffer (PBS, BSA, Glycerol) |

Workflow Visualization and Decision Framework

Comprehensive Nuclei Isolation Workflow

Nuclei Isolation Workflow Decision Framework

This comprehensive workflow illustrates the systematic approach to selecting appropriate nuclei isolation methods based on tissue type and preservation method, followed by core processing steps that ensure high-quality nuclei for downstream snRNA-seq applications.

Quality Control and Validation Pipeline

Quality Control and Validation Pipeline

This quality control pipeline outlines the essential steps for validating nuclei quality before sequencing and verifying data quality after sequencing, ensuring reliable biological interpretations from snRNA-seq experiments.

The advancement of nuclei isolation methods has fundamentally expanded the scope of single-cell transcriptomics to encompass challenging tissue types that were previously inaccessible to such high-resolution analysis. The protocols detailed in this application note—ranging from low-input cryopreserved methods to innovative approaches for FFPE tissues—provide researchers with robust tools to leverage valuable sample repositories that populate clinical biobanks and pathology archives worldwide [10] [17].

As the field continues to evolve, several promising directions are emerging. First, the integration of snRNA-seq with spatial transcriptomics methods will enable the mapping of transcriptional profiles within their native tissue contexts, providing unprecedented insights into cellular organization and communication. Second, multi-omic approaches that combine snRNA-seq with epigenetic profiling or protein analysis from the same nuclei will offer more comprehensive views of cellular states and regulatory mechanisms. Finally, continued optimization of protocols for specific tissue types and disease states will further enhance the sensitivity and specificity of nuclear transcriptomics, solidifying its role as an indispensable tool in both basic research and clinical applications [5] [20].

The methods outlined in this document represent the current state-of-the-art in nuclei isolation for single-nucleus RNA sequencing. By following these optimized protocols and quality control measures, researchers can reliably generate high-quality transcriptional data from even the most challenging tissue specimens, thereby accelerating discoveries in disease mechanisms, developmental biology, and therapeutic development.

Single-cell and single-nucleus RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq and snRNA-seq) have revolutionized plant biology by enabling researchers to uncover the expression profiles of individual cell types within complex tissues [21]. These technologies provide unprecedented insights into cellular diversity, developmental trajectories, and environmental responses that are obscured in bulk RNA sequencing approaches [22]. The success of these high-resolution analyses fundamentally depends on the initial sample preparation steps—specifically, the isolation of individual cells or nuclei from plant tissues. The choice between protoplast isolation and nuclei isolation creates a critical methodological branch point that directly influences data quality, biological interpretation, and integration with emerging spatial transcriptomic technologies [23].

Plant tissues present unique challenges for single-cell analysis due to their rigid cell walls, diverse cell sizes, and high content of interfering organelles such as chloroplasts [22] [21]. While protoplast isolation (enzymatic removal of cell walls) has been widely used, the process can induce stress responses and alter native gene expression patterns [5]. Conversely, nuclei isolation approaches bypass these challenges by focusing on the transcriptome contained within the nucleus, offering advantages for specific applications and tissue types [21] [5]. This application note examines these complementary isolation methodologies within the broader context of spatial transcriptomics, providing structured protocols and analytical frameworks to guide researchers in selecting and implementing optimal strategies for their experimental goals.

Methodological Comparison: Protoplast versus Nuclei Isolation

The decision to use protoplasts or nuclei for single-cell transcriptomics involves balancing multiple factors, including tissue type, research objectives, and practical constraints. The following comparison outlines the core characteristics, advantages, and limitations of each approach.

Table 1: Comparison of Protoplast and Nuclei Isolation Methods for Plant Single-Cell Transcriptomics

| Feature | Protoplast Isolation | Nuclei Isolation |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Enzymatic digestion of cell wall to release intact cells [5] | Mechanical and/or chemical disruption of cell membrane to release nuclei [24] |

| Key Advantage | Captures full cellular transcriptome (cytoplasmic + nuclear RNA) | Bypasses cell wall digestion; suitable for frozen, difficult-to-dissociate, or delicate tissues [25] [24] [5] |

| Major Limitation | Protoplasting process (can take hours) may stress cells and alter transcriptional profiles [5] | Primarily captures the nuclear transcriptome, missing some cytoplasmic transcripts [21] |

| Ideal Tissue Types | Tissues amenable to gentle enzymatic digestion (e.g., seedlings, roots) [5] | Tissues with rigid structures, high secondary metabolites, or high chloroplast content (e.g., leaves, woody tissues, frozen samples) [25] [21] |

| Compatibility with Spatial Transcriptomics | Can provide reference for cell type identification | Excellent; allows mapping of nuclear transcripts to tissue architecture and validation of cell clusters [26] |

The integration of single-nucleus transcriptomic data with spatial techniques is powerfully exemplified by the Arabidopsis life cycle atlas, which leveraged paired single-nucleus and spatial transcriptomic datasets. This integrated approach allowed researchers to annotate 75% of identified cell clusters and spatially validate both known and newly identified cell-type-specific markers across diverse organs and developmental stages [26].

Technical Protocols and Workflows

Nuclei Isolation from Challenging Plant Tissues

Isolating high-quality nuclei is particularly challenging from tissues with high chloroplast content, such as leaves. Standard protocols using DAPI staining for Fluorescent-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) are problematic because DAPI also binds to the plastid genome, leading to significant contamination and an overestimation of nucleus count [21]. The following optimized protocol incorporates a strategic FACS cleanup step to overcome this limitation.

Table 2: Key Reagents for Nuclei Isolation from Leaf Tissue

| Reagent/Consumable | Function/Note |

|---|---|

| Nuclei Isolation Buffer | Typically contains Tris-HCl, MgCl₂, KCl, sucrose, and detergents (e.g., Triton X-100) to lyse plasma membranes while preserving nuclear integrity [24]. |

| DAPI Stain (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) | Fluorescent dye that binds to AT-rich regions of DNA; stains both nuclei and chloroplast DNA [21]. |

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | Added to wash and resuspension buffers (0.5–1%) to prevent nuclei from clumping [24]. |

| RNase Inhibitor | Critical for protecting RNA from degradation during the isolation process [24]. |

| Filters (e.g., 40 μm, 70 μm cell strainers) | Used sequentially to remove large debris and intact cells after tissue homogenization [21] [24]. |

Optimized Protocol for Maize Leaf Tissue [21]:

- Tissue Homogenization: Rapidly harvest and chop approximately 1 cm² of leaf tissue from a 4th fully extended leaf (V5 stage) in ice-cold Nuclei Isolation Buffer. Use a razor blade or gentle douncing to homogenize the tissue and release nuclei. Keep all steps on ice.

- Filtration and Washing: Filter the crude homogenate sequentially through 70 μm and 40 μm cell strainers. Pellet the nuclei by low-speed centrifugation (300–500 × g for 5 minutes). Gently resuspend the pellet in fresh isolation buffer and repeat the washing step to remove cell debris.

- FACS with Double-Filter Strategy: Stain the nuclei suspension with DAPI. Use a FACS sorter equipped with a 488 nm blue laser and two detection filters.

- First, use the Peridinin-Chlorophyll-Protein (PerCP) filter (670/30 nm bandpass) to identify and exclude (negatively select) events that emit in this range, which correspond to autofluorescent chloroplasts.

- Second, use the DAPI filter (450/50 nm bandpass) to select (positively select) the DAPI-positive population.

- Finally, gate the selected population based on size and granularity (FSC vs SSC) to collect intact nuclei.

- Quality Control and Storage: Resuspend the sorted nuclei in a suitable storage buffer with RNase inhibitor. The nuclei can be used directly for library preparation or frozen at –80 °C for a short period (2–3 days maximum).

This FACS strategy significantly reduces chloroplast contamination, leading to improved genome and transcriptome alignment rates and a higher number of detected genes in subsequent snRNA-seq libraries [21].

A Protoplasting-Free snRNA-seq Approach for Capturing Rapid Responses

For studies investigating rapid biological processes, such as early immune responses to microbes, the lengthy protoplasting process is a significant confounder. A protoplasting-free single-nucleus RNA-seq approach has been developed to overcome this, enabling the capture of genuine transcriptional responses that occur within minutes of stimulation [5].

Application Protocol for Root-Microbe Interactions [5]:

- Treatment and Harvest: Treat Arabidopsis roots with microbes (e.g., beneficial Pseudomonas simiae WCS417 or pathogenic Ralstonia solanacearum GMI1000) or a mock control in a hydroponic system for a short duration (e.g., 6 hours). Immediately harvest and flash-freeze the whole roots in liquid nitrogen.

- Nuclei Extraction from Frozen Tissue: Grind the frozen root tissue to a fine powder in a pre-cooled mortar and pestle under liquid nitrogen. Gently homogenize the powder in a nuclei isolation buffer, using a detergent like Triton X-100 to lyse cellular membranes while preserving nuclear integrity [24].

- Nuclei Purification: Filter the homogenate through a series of cell strainers (e.g., 100 μm, 70 μm, and 40 μm) to remove debris. Purify the nuclei via centrifugation through a sucrose cushion or by using optimized washing steps.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Proceed directly to single-nucleus library preparation using a droplet-based (e.g., 10X Genomics) or plate-based platform without a protoplasting step.

This method successfully captured distinct, cell-type-specific transcriptional programs in root cells in response to beneficial and pathogenic microbes within 6 hours of interaction, a feat difficult to achieve with protoplast-based methods [5].

Integration with Spatial Transcriptomics

The relationship between isolation methods and spatial transcriptomics is synergistic rather than competitive. High-quality single-cell or single-nucleus atlases provide the essential reference data needed to deconvolute the spot-based data generated by many spatial transcriptomics platforms, where each spot may contain transcripts from multiple cells [26] [23].

The power of this integration is vividly demonstrated by the creation of a single-cell and spatial transcriptomic atlas of the Arabidopsis life cycle. In this study, the paired single-nucleus and spatial transcriptomic datasets were instrumental for:

- Confident Cell Annotation: Enabling the annotation of 75% (138/183) of the cell clusters identified from over 400,000 nuclei [26].

- Spatial Validation: Allowing for the in situ validation of both known and newly discovered cell-type-specific marker genes across ten developmental stages, from seeds to siliques [26].

- Uncovering Spatial Complexity: Revealing transient cellular states and spatial expression patterns underlying developmental structures, such as the apical hook, which would be difficult to resolve using either technique alone [26].

The selection of an appropriate isolation method—protoplasts or nuclei—is a critical first step that lays the foundation for successful single-cell and spatial transcriptomic studies in plants. While protoplasts can provide a full cellular transcriptome, nuclei isolation offers a robust and often less disruptive alternative for challenging tissues, frozen samples, and studies of rapid transcriptional responses.

The future of plant single-cell omics lies in the deeper integration of these isolation methods with multimodal assays, including spatial transcriptomics, chromatin accessibility (snATAC-seq), and proteomics [23]. Community-driven efforts to build more comprehensive reference atlases and develop computational tools for data integration will be crucial. Furthermore, continued optimization of wet-lab protocols, such as the FACS-based chloroplast removal method presented here, will be essential to overcome persistent technical hurdles like organellar contamination and ambient RNA, ultimately providing a clearer window into the intricate spatial architecture of plant tissues.

Step-by-Step Protocols: From Tissue to Viable Protoplasts and Nuclei

In single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) research, the isolation of high-quality protoplasts or nuclei is a critical first step for successful transcriptomic analysis. The process of protoplast isolation relies on an enzymatic cocktail to digest the plant cell wall, and its composition must be meticulously optimized to maximize yield and viability while preserving transcriptomic integrity. This protocol details the systematic optimization of the core components—Cellulase, Macerozyme, and the osmoticum Mannitol—framed within the context of preparing samples for scRNA-seq. The guidelines provided are essential for generating robust and reproducible data in plant functional genomics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details the key reagents required for the efficient isolation of protoplasts for scRNA-seq studies.

Table 1: Essential Reagents for Protoplast Isolation

| Reagent | Function in Protocol | Key Considerations for scRNA-seq |

|---|---|---|

| Cellulase R-10 | Hydrolyzes cellulose, the primary component of the plant cell wall [27] [7] [12]. | Concentration must be optimized to balance complete cell wall digestion and maintenance of cellular health for accurate transcriptomic profiles [27] [12]. |

| Macerozyme R-10 | Degrades pectin and hemicellulose in the middle lamella, facilitating cell separation [27] [7] [12]. | Often used in conjunction with cellulase; its concentration is critical for efficiently liberating individual cells without inducing stress responses [27]. |

| Pectolyase Y-23 | A specific pectinase that can enhance digestion efficiency, particularly in woody tissues [27] [28]. | Not always required, but its inclusion can significantly improve protoplast yield from more recalcitrant species like poplar [27]. |

| Mannitol | Serves as an osmotic stabilizer to prevent protoplast lysis by maintaining osmotic balance [27] [7] [12]. | Critical for preserving protoplast viability. The concentration is species-dependent and must be optimized to match the internal osmotic pressure of the source tissue [27] [7]. |

| MES Buffer | Maintains a stable pH (typically 5.7-5.8) in the enzyme solution [27] [7]. | A stable pH ensures consistent enzyme activity during the digestion process. |

| Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂) | Helps stabilize the protoplast plasma membrane [7] [12]. | Contributes to protoplast integrity and health during and after isolation. |

Optimized Enzyme and Mannitol Concentrations

Based on recent studies across various plant species, the optimal concentration of enzymes and Mannitol varies. The following table summarizes successful formulations for different research applications.

Table 2: Optimized Enzyme Cocktail Formulations for Different Plant Species

| Plant Species | Tissue | Cellulase R-10 (%) | Macerozyme R-10 (%) | Pectolyase Y-23 (%) | Mannitol (M) | Primary Application | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Populus simonii × P. nigra | Leaf | 2.5 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.8 | Transient gene expression & subcellular localization [27] [28] | [27] [28] |

| Cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) | Taproot | 1.5 | 0.75 | Not Used | 0.4 | scRNA-seq & transient expression [7] | [7] |

| Coconut (Cocos nucifera) | Protoplast | Protocol specified use of Cellulase and Macerozyme, but exact concentrations were not detailed in the provided excerpt. | CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing [29] | [29] | |||

| Moss (Physcomitrium patens) | Protonemal tissue | 1.5 | 0.5 | Not Used | 0.8 (as 8.5% solution) | PEG-mediated transformation [30] | [30] |

| Solanum Genus (e.g., Tomato, Potato) | Leaf / Hypocotyl | 1.5 – 2.0 | ~0.4 (as part of "Macerozyme" which contains pectinase) | Not Used | 0.4 - 0.6 | CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing (protoplast regeneration) [12] | [12] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Protoplast Isolation

Sample Preparation

- Plant Material: Use young, healthy tissues. For Populus simonii × P. nigra, use the 2nd to 4th young true leaves from tissue culture seedlings [27] [28]. For cotton taproots, use roots from seedlings grown in hydroponics for 65-75 hours after germination [7].

- Tissue Processing: Remove main veins and slice tissue into 0.5–1 mm thin strips using a sharp blade to maximize surface area for enzyme contact [27] [7].

Enzymatic Digestion

- Solution Preparation: Freshly prepare an enzyme solution containing MES buffer (20 mM, pH 5.8), KCl (20 mM), CaCl₂ (10 mM), BSA (0.1%), and the optimized concentrations of Cellulase R-10, Macerozyme R-10, Pectolyase Y-23 (if required), and Mannitol as defined in Table 2 [27] [7].

- Digestion Process: Incubate the tissue slices in the enzyme solution in the dark with gentle shaking (40-80 rpm). The optimal digestion time is typically 3-5 hours at 27°C, but this should be determined empirically [27] [7].

Protoplast Purification and Quality Control

- Filtration and Washing: After digestion, filter the mixture through a 30-40 μm cell strainer to remove undigested debris [7]. Wash the protoplasts by centrifuging at 100×g for 2-5 minutes and resuspending the pellet in W5 solution (154 mM NaCl, 125 mM CaCl₂, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM MES, pH 5.7) [27] [7].

- Viability and Yield Assessment:

Workflow for Protoplast Isolation and scRNA-seq

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow from tissue preparation to single-cell analysis, highlighting key decision points for quality control.

Critical Considerations for scRNA-seq Applications

For protoplasts intended for scRNA-seq, additional stringent criteria must be met:

- Cell Viability: A viability rate of >93% is achievable with optimized protocols and is crucial for obtaining high-quality transcriptome data [7].

- Cell Size: The diameter of isolated protoplasts must be less than 40-50 μm to be compatible with droplet-based scRNA-seq platforms like the 10x Genomics Chromium system [7]. Use appropriate cell strainers (e.g., 30 or 40 μm) during purification.

- Inhibitor Removal: Protoplasts for scRNA-seq should be resuspended in Mannitol solution instead of MgCl₂ or CaCl₂-based buffers (like MMG), as high concentrations of divalent cations can interfere with subsequent reverse transcription reactions [7].

- Minimizing Stress: The isolation process should be as rapid as possible to minimize the induction of stress-related genes that could confound the biological interpretation of the scRNA-seq data [31].

The successful application of scRNA-seq in plant research is fundamentally dependent on the initial steps of protoplast isolation. As demonstrated by protocols in species from poplar to cotton, careful optimization of the enzymatic cocktail—specifically the concentrations of Cellulase, Macerozyme, and the osmotic stabilizer Mannitol—is non-negotiable for achieving high yields of viable, stress-free protoplasts. The parameters and protocols detailed herein provide a reliable foundation for researchers to adapt and refine for their specific plant systems, thereby enabling robust and insightful single-cell transcriptomic studies.

Within the burgeoning field of plant single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), the isolation of high-quality protoplasts or nuclei is the critical first step upon which all subsequent data hinges. This application note provides a detailed framework for optimizing the key pre-analytical parameters of tissue type, developmental age, and enzymolysis time to maximize protoplast yield and viability. The protocols herein are designed for researchers aiming to establish robust, reproducible systems for studying cellular heterogeneity, stress responses, and developmental trajectories in plants, with a specific focus on cotton as a model for complex crops [32] [20]. The success of scRNA-seq in illuminating plant biology at unprecedented resolution is well-established [33], yet its application is often gated by the ability to efficiently isolate viable single cells, making the optimization of these foundational steps paramount.

Critical Parameters and Optimization Data

The yield and viability of protoplasts are highly sensitive to the biological source and dissociation conditions. Systematic optimization of these parameters is essential for generating scRNA-seq data that accurately represents the original tissue cellular composition. The following table summarizes the optimal conditions identified for cotton root tissues, which can serve as a guide for protocol development in other species.

Table 1: Optimal Conditions for Protoplast Isolation from Cotton Roots

| Parameter | Optimal Condition | Quantitative Outcome | Impact on scRNA-seq Quality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue Type | Taproots from hydroponically grown seedlings [32] | High yield and minimal tissue fragments [32] | Ensures representative sampling of root cell types. |

| Tissue Age | 5-day-old root tips [34] OR 72 hours (3 days) post-germination in hydroponics [32] | • 5-day-old: >85% viability [34] • ~72-hour: 93.3% viability, yield of 3.55 x 10⁵ protoplasts/gram [32] | Younger tissues have thinner cell walls, facilitating easier dissociation and higher viability, meeting the >80% viability requirement for platforms like 10X Genomics [32] [35]. |

| Enzymolysis Time | 6 hours [34] OR 3 hours + optional 1-hour incubation [32] | Peak yield at 6 hours (2.00 x 10⁶ protoplasts g⁻¹ fresh weight); viability decreases significantly by 8 hours [34] | Insufficient digestion reduces yield; over-digestion compromises cell integrity and RNA quality. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: Isolation of Root Tip Protoplasts fromGossypium arboreum

This protocol, adapted from a study investigating salt stress responses, is optimized for 5-day-old root tips and includes a vacuum infiltration step to enhance enzyme penetration [34].

Materials & Reagents:

- Enzyme Solution: 1.5% Cellulase R10, 0.75% Macerozyme R10, 0.4M mannitol, 20mM KCl, 20mM MES (pH 5.7), 10mM CaCl₂, 0.1% BSA [32] [34].

- W5 Solution: 154 mM NaCl, 125 mM CaCl₂, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM MES (pH 5.7) [32].

- Equipment: Laminar flow hood, sterile razor blades, 50mL conical flasks, platform shaker, vacuum desiccator, 40μm cell strainer, swinging-bucket centrifuge.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Plant Material Preparation: Surface-sterilize cotton seeds and germinate on moist towels in the dark at 25°C for approximately 36 hours. Transfer germinated seeds to hydroponic culture under a 16/8 hour light/dark cycle at 28/25°C for 5 days [34].

- Tissue Harvesting: Excise root tips (approximately 1-2 cm) from 5-day-old seedlings using a sterile razor blade. Quickly slice the root tips into 0.5-1 mm thick sections into a Petri dish containing enzyme solution to prevent desiccation.

- Vacuum Infiltration: Transfer the tissue slices and enzyme solution into a 50mL conical flask. Place the flask in a vacuum desiccator and apply a vacuum of 0.05 MPa for 1 hour. This step forces the enzyme solution into intercellular spaces, significantly improving dissociation efficiency [34].

- Enzymatic Digestion: After infiltration, incubate the flask on a platform shaker at 40-50 rpm for 6 hours at 25°C in the dark [34].

- Protoplast Release and Filtration: Gently add an equal volume of W5 solution to the digestion mixture and agitate for 10 seconds to release protoplasts. Filter the resulting suspension through four layers of Miracloth to remove undigested debris, then pass the filtrate through a moistened 40μm cell strainer into a 50mL round-bottom tube [32].

- Protoplast Washing: Centrifuge the filtered protoplast suspension at 100 g for 5 minutes in a swinging-bucket rotor with low acceleration/deceleration settings. Carefully aspirate the supernatant and resuspend the pellet in an appropriate volume of W5 solution or mannitol for counting and viability assessment.

Protocol B: High-Viability Taproot Protoplast Isolation for Transfection

This protocol emphasizes speed and high viability for applications like transient transfection and CRISPR vector validation, using slightly younger tissue and a shorter digestion time [32].

Materials & Reagents: (As in Protocol A)

- Additional Reagent: MMG solution (for transfection) [32].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Plant Material and Hydroponics: Surface-sterilize and germinate seeds as in Protocol A. Transfer seedlings to hydroponics and grow for 65-75 hours. The 72-hour time point is critical for achieving the highest viability [32].

- Tissue Dissection: Harvest taproots from 25-50 seedlings. Slice roots into 0.5-1 mm sections directly into pre-chilled enzyme solution. Using sharp blades and processing 5-7 roots at a time is recommended for efficiency [32].

- Enzymatic Digestion: Digest the tissue slices for 3 hours with shaking at 40-50 rpm at 25°C in the dark. Monitor protoplast release microscopically [32].

- Protoplast Release: Add an equal volume of W5 solution and shake vigorously for 10 seconds. Filter through Miracloth and a 40μm cell strainer as in Protocol A.

- Yield Maximization (Optional): For increased yield, return the tissue residue on the Miracloth to the flask with 10mL of fresh W5 solution and incubate for an additional hour with shaking before repeating the filtration and centrifugation steps [32].

- Assessment: Determine protoplast yield and viability using a hemocytometer and vital stains like fluorescein diacetate (FDA). Viability should exceed 90% for optimal transfection performance [32].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and decision points in the protoplast isolation workflow, integrating the critical parameters discussed.

Protoplast Isolation and Quality Control Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

A successful protoplast isolation experiment relies on a carefully selected suite of reagents and tools. The following table details the core components and their specific functions in the protocol.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Protoplast Isolation

| Item | Function/Application | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cellulase R10 | Enzyme that hydrolyzes cellulose in the primary cell wall. | Yakult (Japan). Critical for breaking down the structural framework of plant cells [32] [34]. |

| Macerozyme R10 | Enzyme that degrades pectins and hemicelluloses in the middle lamella. | Yakult (Japan). Works synergistically with cellulase to dissociate individual cells [32] [34]. |

| Mannitol | Osmoticum. | Creates an isotonic environment in the enzyme and resuspension solutions to prevent protoplast bursting [32]. |

| MES Buffer | pH stabilization. | Maintains the enzyme solution at an optimal pH (5.7) for enzymatic activity [32]. |

| CaCl₂ | Membrane stabilizer. | Added to the enzyme and W5 solutions to enhance protoplast membrane integrity and viability [32]. |

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | Protein supplement. | Reduces adsorption of protoplasts to surfaces and may inhibit proteases [32]. |

| Miracloth & Cell Strainers | Filtration and debris removal. | MilliporeSigma. Used in sequence to remove undigested tissue (Miracloth) and select for protoplasts <40μm (strainer), which is crucial for droplet-based scRNA-seq [32] [35]. |

The meticulous optimization of tissue type, age, and enzymolysis time is non-negotiable for obtaining protoplasts that are both abundant and viable, forming the foundation for high-quality single-cell genomics data. The protocols and parameters detailed here provide a validated roadmap for researchers in plant biology and biotechnology. By adhering to these guidelines, scientists can accelerate functional genomics studies, improve the efficiency of genome editing validation in crops like cotton, and ultimately contribute to the development of precision breeding strategies [32] [20] [33]. As single-cell technologies continue to evolve, these robust and reproducible isolation methods will remain a cornerstone of plant systems biology.

In the context of advancing single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and single-nuclei RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) research, reliable and rapid validation of genome editing reagents is a critical preliminary step. While scRNA-seq analyzes the transcriptome of individual intact cells, and snRNA-seq focuses specifically on nuclear transcripts, both technologies rely on high-quality single-cell or single-nuclei suspensions [36] [37]. Protoplast systems, which are plant cells devoid of cell walls, provide a versatile platform for the transient validation of CRISPR/Cas9 components before undertaking lengthy stable transformation and plant regeneration experiments [38] [12]. Polyethylene glycol (PEG)-mediated transfection of protoplasts offers a direct and efficient method for delivering plasmid DNA or pre-assembled ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes into plant cells, enabling the functional assessment of guide RNAs (gRNAs) within a native cellular environment [12] [39]. This application note details optimized protocols for protoplast isolation, PEG-mediated transfection, and subsequent analysis of editing efficiency, providing a framework that integrates seamlessly with single-cell genomics workflows.

Key Experimental Parameters and Optimized Conditions

Successful validation of CRISPR reagents hinges on obtaining a high yield of viable protoplasts and achieving efficient transfection. The following parameters are critical and have been optimized across various plant species.

Plant Material and Protoplast Isolation

The choice of plant material significantly impacts protoplast yield and viability. Young, tender tissues with thin cell walls, such as leaves from seedlings, roots from hydroponically grown plants, or established suspension cell cultures, are ideal [7] [39]. For example, using cotton taproots from seedlings grown in hydroponics for 72 hours yielded up to 3.55 × 10⁵ protoplasts per gram with 93.3% viability [7]. The enzymatic digestion mixture, typically containing cellulase and macerozyme, must be optimized for concentration and incubation time. A digestion period of 3-5 hours is commonly effective for many species, including rice and cotton [38] [7]. Incorporating a sucrose gradient purification step can dramatically improve protoplast viability by removing broken cells and debris. This step increased viable protoplast yields in rice from 50% to 80% and in Arabidopsis from 50% to 76% [38]. Maintaining osmotic stability with 0.4-0.6 M mannitol in all solutions is essential to prevent protoplast rupture [38] [13] [11].

Transfection and Validation

For PEG-mediated transfection, key variables include the concentration of PEG, the amount of plasmid DNA, and the incubation time. A common optimal condition uses 20% PEG with 20 µg of plasmid DNA and a 15-20 minute incubation, achieving transfection efficiencies of approximately 50-80% in species like pea and maize [13] [40]. Using smaller plasmid sizes can further enhance transfection efficiency [38]. The CRISPR reagent format can be either plasmid DNA encoding Cas9 and gRNAs or pre-assembled RNP complexes. The RNP format is a "DNA-free" editing approach that minimizes the risk of transgene integration and reduces off-target effects [12]. After transfection, a rapid viability assessment using dyes like Evans Blue or Fluorescein Diacetate (FDA) is crucial. FDA staining in rice showed 91% viability with a sucrose gradient step, compared to 60% without it [38]. Editing efficiency is typically validated by extracting genomic DNA from transfected protoplasts and analyzing the target locus using PCR/restriction enzyme (RE) assay, T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) assay, or by sequencing [39]. Using dual gRNAs to create a deletion allows for straightforward detection of editing success via agarose gel electrophoresis [38].

Table 1: Optimized Protoplast Isolation Parameters for Various Plant Species

| Plant Species | Optimal Tissue | Enzyme Solution | Digestion Time | Key Isolation Factor | Reported Viability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice [38] | Seedling leaves | Cellulase R10, Macerozyme R10 | 5 hours | 0.6 M mannitol; Sucrose gradient | >80% |

| Cotton [7] | 72-h hydroponic roots | 1.5% Cellulase R10, 0.75% Macerozyme R10 | 3 hours | Specific root developmental stage | 93.3% |

| Pea [13] | Expanded leaves | Orthogonal optimization of cellulase, macerozyme, mannitol | Not specified | Orthogonal array design (L16) | Not specified |

| Brassica carinata [11] | Leaves (3-4 wk seedlings) | 1.5% Cellulase R10, 0.6% Macerozyme R10 | 14-16 hours | Osmotic pressure maintenance | Not specified |

| Maize [40] | Etiolated seedling leaves | Cellulase R10, Macerozyme R10 | Not specified | Vertical leaf cutting | High (yield 17.88×10⁶/g FW) |

Table 2: Optimized PEG Transfection Parameters for CRISPR Validation

| Species | Plasmid DNA | PEG Concentration | Incubation Time | Efficiency | Key Validated Target |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pea [13] | 20 µg | 20% | 15 min | 59 ± 2.64% | PsPDS (97% mutagenesis) |

| Maize [40] | 10 µg | Not specified | Not specified | ~50% | Floral repressors (ZmCCT9,10) |

| Rice [38] | 10-30 µg | Not specified | 20 min | 55-80% | Various (height, yield, stress) |

| Cotton [7] | 20 µg | Not specified | 20 min | 80% | CRISPR vector efficiency |

| Brassica carinata [11] | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 40% (GFP marker) | Protocol established |

Detailed Experimental Workflow

The following section provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for the isolation, transfection, and validation of CRISPR reagents in plant protoplasts, consolidating best practices from the cited literature.

Protocol: Protoplast Isolation and Transfection

Step 1: Preparation of Plant Material

- Rice, Arabidopsis, Brassica carinata: Surface-sterilize seeds and germinate on half-strength Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium under a 16-h light/8-h dark photoperiod at 24-25°C. Use fully expanded leaves from 3- to 4-week-old seedlings [38] [11].

- Cotton: Germinate surface-sterilized seeds hydroponically. Use taproots from seedlings after 65-75 hours of hydroponic culture for optimal results [7].

- Tomato: If leaf mesophyll protoplasts are recalcitrant, establish a suspension cell culture from hypocotyl-derived callus as a reliable protoplast source [39].

Step 2: Tissue Pre-treatment and Digestion

- Using a sharp razor blade, slice leaves or roots into thin, 0.5-1 mm strips. For monocot seedlings like rice and maize, longitudinal cutting has been shown to significantly increase protoplast yield compared to cross-cutting [39].

- Immerse the tissue strips in a plasmolysis solution (e.g., 0.4-0.6 M mannitol) and incubate in the dark at room temperature for 30 minutes [11].

- Replace the plasmolysis solution with a freshly prepared enzyme solution. A common effective formulation contains 1.5% (w/v) Cellulase Onozuka R10, 0.4-0.6% (w/v) Macerozyme R10, 0.4-0.6 M mannitol, 10-20 mM MES (pH 5.7), 10 mM CaCl₂, and 0.1% BSA [38] [11] [7].

- Incubate the digestion mixture in the dark at 25°C with gentle shaking (40-50 rpm) for 3-5 hours, or 14-16 hours for some species like Brassica carinata [38] [11].

Step 3: Protoplast Purification

- After digestion, add an equal volume of W5 solution (154 mM NaCl, 125 mM CaCl₂, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM MES, pH 5.7) to the enzyme mixture and swirl gently to release the protoplasts [11] [7].

- Filter the resulting suspension through a 40 µm nylon mesh to remove undigested tissue. For scRNA-seq applications where smaller cell sizes are required, a 30 µm strainer may be used [7].

- Centrifuge the filtrate at 100 × g for 5-10 minutes using a swinging-bucket rotor with soft acceleration/deceleration settings to gently pellet the protoplasts [7].

- Carefully remove the supernatant and resuspend the pellet in a small volume of W5 solution. For further purification, layer the protoplast suspension over a sucrose gradient and centrifuge. Intact, viable protoplasts will collect at the interface [38].

- Resuspend the purified protoplasts in an appropriate volume of 0.5 M mannitol or MMG solution (0.4 M mannitol, 15 mM MgCl₂, 4 mM MES, pH 5.7) and keep on ice. Determine protoplast concentration and viability using a hemocytometer and FDA or Evans Blue staining [38] [11].

Step 4: PEG-Mediated Transfection

- Aliquot 2 × 10⁵ to 1 × 10⁶ protoplasts in a 2 mL microcentrifuge tube.

- Add 10-20 µg of plasmid DNA (e.g., a vector expressing Cas9 and sgRNAs) or an equivalent amount of pre-assembled RNP complexes to the protoplasts. Gently mix [13] [40].

- Add an equal volume of freshly prepared PEG solution (40% PEG-4000, 0.2 M mannitol, 0.1 M CaCl₂) to the protoplast-DNA mixture. Incubate at room temperature for 15-20 minutes [13].

- Carefully stop the transfection by diluting the mixture stepwise with W5 solution (e.g., add 1 mL, then 2 mL, then 4 mL with gentle mixing between additions).

- Centrifuge at 100 × g for 5 minutes, remove the supernatant, and resuspend the transfected protoplasts in 1-2 mL of appropriate culture medium (e.g., WI solution [0.5 M mannitol, 4 mM MES, 20 mM KCl]). Culture in the dark at 25°C for 16-48 hours to allow gene expression and genome editing to occur [38].

Analysis of Editing Efficiency

Genomic DNA Extraction and Mutation Detection

- After the incubation period, harvest the protoplasts by centrifugation. Extract genomic DNA using a standard CTAB method or a commercial kit.

- Amplify the targeted genomic region by PCR using gene-specific primers that flank the CRISPR target site.

- Analyze the PCR products for mutations using one of the following methods:

- PCR/RE Assay: If the target site is within a restriction enzyme recognition sequence, digest the PCR products with the corresponding enzyme. Successful editing will destroy the site, resulting in uncut bands visible on an agarose gel [39].

- T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) Assay: Denature and reanneal the PCR products. T7E1 cleaves heteroduplex DNA formed by wild-type and mutant strands. Cleavage bands indicate mutation [39].

- Deletion Detection: When using two gRNAs to create a deletion, successful editing can be detected by a smaller PCR product on an agarose gel, providing a simple and visual confirmation [38].

- Sanger Sequencing or NGS: For the most accurate quantification of editing efficiency and characterization of specific mutation types, PCR products can be cloned and Sanger sequenced, or directly subjected to next-generation sequencing [38] [39].

Single-Cell Mutation Analysis

- For a more precise measurement of efficiency, individual transfected protoplasts can be isolated manually using a capillary pipette under a microscope into separate PCR tubes.

- The genomic DNA from a single protoplast is then used as a template for a nested-PCR to amplify the target locus, which is subsequently sequenced to determine the genotype of that specific cell [39].

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Workflow for CRISPR reagent validation in protoplasts.

Diagram 2: Integration of protoplast validation with scRNA/snRNA-seq research.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Protoplast-based CRISPR Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Specifications / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cellulase Onozuka R10 [38] [11] [7] | Digests cellulose in plant cell walls. | Typical working concentration: 1.5-2% (w/v). |

| Macerozyme R10 [38] [11] [7] | Digests pectin and hemicellulose in cell walls. | Typical working concentration: 0.4-0.75% (w/v). |

| Mannitol [38] [13] [12] | Osmoticum to maintain protoplast stability and prevent lysis. | Commonly used at 0.4-0.6 M in all solutions. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) [13] [12] [11] | Facilitates the delivery of DNA or RNPs into protoplasts. | PEG-4000 at 20-40% concentration is standard. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Plasmid [38] [13] | Expresses Cas9 nuclease and guide RNA(s) in plant cells. | Contains plant-specific promoters (e.g., Ubi, 35S). |

| Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complex [12] | Pre-assembled complex of purified Cas9 protein and sgRNA; enables DNA-free editing. | Reduces off-target effects and avoids vector integration. |

| Fluorescein Diacetate (FDA) [38] | Cell-permeant viability dye; fluoresces upon cleavage by intracellular esterases. | Labels live, metabolically active protoplasts. |

| Evans Blue [38] | Cell-impermeant dye; stains dead cells with compromised membranes. | Penetrates and colors non-viable protoplasts. |

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized biological research by enabling transcriptome profiling at the individual cell level, uncovering cellular heterogeneity, and revealing complex biological systems with unprecedented resolution [41]. This transformative technology has become an indispensable tool across diverse fields, from oncology to developmental biology and ecological research. When integrated with powerful genome editing tools like CRISPR and advanced spatial transcriptomics, scRNA-seq forms a comprehensive framework for elucidating gene function, regulatory networks, and subcellular localization patterns. This application note details standardized protocols and methodologies within the context of protoplast and nuclei isolation, providing researchers with practical guidance for implementing these cutting-edge approaches in their investigations.

Experimental Protocols for Sample Preparation

Protoplast Isolation for Plant scRNA-seq

The isolation of high-quality protoplasts is a critical first step for successful plant single-cell RNA sequencing. The following protocol, adapted from established methods for Arabidopsis thaliana, ensures efficient protoplast isolation with maintained cellular integrity [42].

Materials:

- Arabidopsis seeds

- Murashige and Skoog (MS) growth media

- Sterilization solution: 30% (v/v) bleach, 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100

- Enzyme solution: 1.25% (w/v) Cellulase ("ONOZUKA" R-10), 0.1% (w/v) Pectolyase, 0.4 M Mannitol, 20 mM MES (pH 5.7), 20 mM KCl, 10 mM CaCl₂, 0.1% (w/v) bovine serum albumin

- Washing solution: 0.4 M Mannitol, 20 mM MES (pH 5.7), 20 mM KCl, 10 mM CaCl₂, 0.1% (w/v) bovine serum albumin

- Filters: 70-μm and 40-μm strainers

Procedure:

- Surface Sterilization and Growth: Surface-sterilize Arabidopsis seeds using the sterilization solution for 10 minutes. Incubate on MS growth media covered with 100/47 µm mesh under 16-hour light/8-hour dark conditions.

- Tissue Harvesting: At 5 days after germination, cut primary root tips and place into a 35-mm diameter dish containing a 70-μm strainer and 4 mL enzyme solution.

- Enzymatic Digestion: Rotate the dish at 85 rpm for 1 hour at 25°C to digest cell walls and release protoplasts.

- Centrifugation and Resuspension: Centrifuge the cell solution at 500 g for 10 minutes and resuspend the pellet in 500 μL washing solution.

- Filtration: Strain the protoplast solution sequentially through a 70-μm filter, then twice through a 40-μm filter to remove undigested debris and cell clumps.

- Final Purification: Centrifuge the filtered solution at 200 g for 6 minutes and resuspend the pelleted protoplasts in 30–50 μL washing solution to achieve the desired concentration (approximately 10⁴ protoplasts/mL).

Quality Control: Assess protoplast viability and integrity using microscopy before proceeding to library preparation. The isolated protoplasts are now ready for loading onto droplet-based scRNA-seq platforms such as the 10X Genomics Chromium system.

Nuclei Isolation from Low-Input Cryopreserved Tissues

For tissues where protoplast isolation is challenging or when working with cryopreserved samples, single-nuclei RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) provides a robust alternative. This optimized protocol enables nuclei extraction from just 15 mg of cryopreserved human tissue [10].

Materials:

- Cryopreserved tissue samples (brain, bladder, lung, prostate)

- Ice-cold lysis buffer: 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl₂·6H₂O, 0.05% NP-40

- Nuclei washing buffer: 0.5X PBS, 5% BSA, 0.25% Glycerol, 40 units/mL Protector RNAse inhibitor

- Iodixanol (Optiprep) solution: 29% and 50% (wt/vol)

- Dounce homogenizer with loose (A) and tight (B) pestles

- 30-μm MACS strainers

- Staining solution: 7-AAD viability dye

Procedure:

- Tissue Mincing: Mince cryopreserved samples in a pre-cooled mortar on dry ice using a scalpel and transfer to 15 mL tubes.

- Homogenization: Add 3 mL ice-cold lysis buffer and homogenize with a Dounce homogenizer. The number of strokes and pestle type (A or B) should be optimized for each tissue type as detailed in Table 1.

- Lysis Incubation: Incubate homogenized samples on ice for 5 minutes after adding 2 mL additional ice-cold lysis buffer.

- Reaction Termination: Stop the lysis reaction with 5 mL ice-cold nuclei washing buffer.

- Filtration and Centrifugation: Filter samples through 30-μm MACS strainers and centrifuge for 10 minutes at 1000 g (4°C).

- Density Gradient Purification: Resuspend pellets in 1 mL nuclei washing buffer, add 1 mL of 50% iodixanol solution, and gently layer over a 2 mL cushion of 29% iodixanol. Centrifuge and collect the purified nuclei fraction.

- Nuclei Staining and Sorting: Stain nuclei with 7-AAD for 10 minutes and sort using a BD FACSAria Fusion cell sorter with a 70-μm nozzle. Collect fluorescent-positive events within appropriate size limits determined by calibration beads.

- Final Preparation: Centrifuge sorted nuclei at 1000 g for 10 minutes at 4°C and resuspend in an appropriate volume for snRNA-seq.

Table 1: Tissue-Specific Homogenization Parameters

| Tissue Type | Pestle Type | Number of Strokes | Additional Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brain | B (tight) | 10-15 | Gentle homogenization to preserve nuclear integrity |

| Bladder | A (loose) | 5-10 | Moderate mechanical force |

| Lung | B (tight) | 10-12 | Can be fibrous; may require optimization |