Strategies for Reducing Seed Batch Effects in Plant Physiology Experiments: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Correction Techniques

This comprehensive article addresses the critical challenge of batch effects in plant physiology research, providing scientists and researchers with a complete framework for understanding, identifying, and correcting technical variations in...

Strategies for Reducing Seed Batch Effects in Plant Physiology Experiments: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Correction Techniques

Abstract

This comprehensive article addresses the critical challenge of batch effects in plant physiology research, providing scientists and researchers with a complete framework for understanding, identifying, and correcting technical variations in seed experiments. Covering foundational concepts through advanced methodologies, we explore how batch effects originating from genetic heterogeneity, environmental conditions, and technical processing can compromise data integrity and reproducibility. The content delivers practical strategies for experimental design, statistical correction methods including ComBat and harmony algorithms, validation metrics, and troubleshooting guidance specifically tailored for seed biology applications across transcriptomics, metabolomics, and phenotypic analyses. By synthesizing current best practices and emerging technologies, this resource enables researchers to enhance data quality and reliability in plant science investigations.

Understanding Seed Batch Effects: Defining the Problem and Its Impact on Plant Research

What Are Batch Effects? Systematic Technical Variations in Seed Experiments

Batch effects are systematic technical variations in data that are introduced by non-biological factors during an experiment. In molecular biology, these effects occur when non-biological factors cause changes in the data, which can lead to inaccurate conclusions, especially when the technical variations are correlated with the biological outcomes being studied [1]. In the context of seed experiments, these could be variations in laboratory conditions, reagent lots, personnel, or the time of day when measurements are taken [1].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What exactly is a batch effect in plant physiology experiments?

A batch effect is unwanted technical variation that can confound your data. It arises when seeds or samples processed under different technical conditions (e.g., on different days, by different people, or using different reagent lots) show systematic differences in measurements that are not due to your experimental treatment or biological reality [1] [2]. For example, seeds germinated and measured in Batch A might consistently show different gene expression or metabolite levels compared to genetically identical seeds processed in Batch B, purely due to technical artifacts.

Why is correcting for batch effects so critical in seed research?

Correcting batch effects is crucial for ensuring the reliability and reproducibility of your findings. Uncorrected batch effects can [2] [3]:

- Generate false positives: Identify genes or metabolites as significantly different when the variation is actually technical.

- Mask true signals: Obscure real biological differences between treatment and control groups.

- Lead to irreproducible results: Cause findings that cannot be replicated in subsequent experiments, potentially invalidating conclusions and wasting resources.

My experiment is small and seems well-controlled. Do I still need to worry?

Yes. Batch effects are notoriously common in high-throughput biological data [1]. Even in a well-controlled single-laboratory setting, subtle shifts can occur across different sequencing runs, reagent batches, or sample preparation days. It is always best practice to assess your data for batch effects before drawing biological conclusions [3].

Can batch correction accidentally remove real biological signals?

Yes, this is a known risk called over-correction. It is most likely to happen if your biological groups are perfectly confounded with batches (e.g., all control seeds were processed in one batch and all treated seeds in another) [4] [5]. This is why a good experimental design, which randomizes biological groups across batches, is the first and most important defense. When correction is necessary, choosing an appropriate method and validating the results are essential to preserve biological variation [3].

How many batches do I need to consider correction methods?

Most statistical batch correction methods require at least two batches to model and remove the technical variation. To build a robust model, it is ideal to have multiple samples from each biological group distributed across different batches [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Identifying Batch Effects in Your Dataset

Before correction, you must diagnose whether your data is affected by batch effects.

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Perform Unsupervised Clustering: Use Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or UMAP to visualize your data.

- Color Plots by Batch: Color the data points in your PCA or UMAP plot based on their technical batch (e.g., processing day, sequencing run).

- Color Plots by Biology: Create a second plot coloring the same data points by the key biological variable (e.g., treatment vs. control, different seed varieties).

- Interpret Results: If the data points cluster strongly by batch in the first plot, rather than by biological group in the second plot, a batch effect is likely present [3] [5].

Quantitative Assessment Metrics:

Beyond visual inspection, several metrics can quantify batch effects. The following table summarizes key diagnostic metrics.

Table 1: Quantitative Metrics for Assessing Batch Effects

| Metric | Description | What It Measures | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| kBET [6] [7] | k-nearest neighbor Batch Effect Test | Tests if local neighborhoods of cells/samples have a balanced mix of batches. | A high rejection rate indicates strong batch effects. |

| LISI [6] [7] | Local Inverse Simpson's Index | Measures the diversity of batches within a local neighborhood. | A higher Batch LISI score indicates better batch mixing. |

| ASW [3] | Average Silhouette Width | Quantifies how similar a sample is to its own batch vs. other batches. | Values closer to 0 indicate better mixing (no clear batch structure). |

Guide 2: Correcting Batch Effects in Transcriptomics Data

This guide focuses on correcting gene expression data from seed experiments (e.g., bulk or single-cell RNA-seq).

Detailed Methodology:

- Choose a Correction Method: Select an algorithm based on your data type and the nature of your batches. The table below compares common methods.

- Apply the Correction: Use the chosen tool, ensuring you provide the correct batch labels and, if needed, a model of your biological conditions to protect them from removal.

- Validate the Correction: Always repeat the diagnostic steps from Guide 1 on your corrected data. Successful correction should show:

- Visually: Data points from different batches are intermingled in PCA/UMAP plots.

- Biologically: Clustering by your key biological variable is now the dominant pattern.

- Quantitatively: Improved scores on metrics like kBET, LISI, and ASW [3].

Table 2: Comparison of Common Batch Effect Correction Methods

| Method | Best For | Key Principle | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ComBat [3] [8] | Bulk RNA-seq | Empirical Bayes framework to adjust for known batches. | Simple, widely used, effective for known batch effects. | Requires known batch info; may not handle complex non-linear effects. |

| limma removeBatchEffect [3] [5] | Bulk RNA-seq | Linear model to remove batch variation. | Fast, integrates well with differential expression workflows. | Assumes additive batch effects; requires known batches. |

| SVA [1] [3] | Bulk RNA-seq | Estimates and removes "surrogate variables" representing hidden batch effects. | Does not require pre-specified batch labels. | Risk of removing biological signal if not carefully modeled. |

| Harmony [4] [7] | scRNA-seq | Iterative clustering in a low-dimensional space to integrate datasets. | Fast, scalable, preserves biological variation well. | Limited native visualization tools. |

| Seurat Integration [4] [7] | scRNA-seq | Uses mutual nearest neighbors (MNN) or CCA to find shared biological states across batches. | High biological fidelity; part of a comprehensive toolkit. | Can be computationally intensive for very large datasets. |

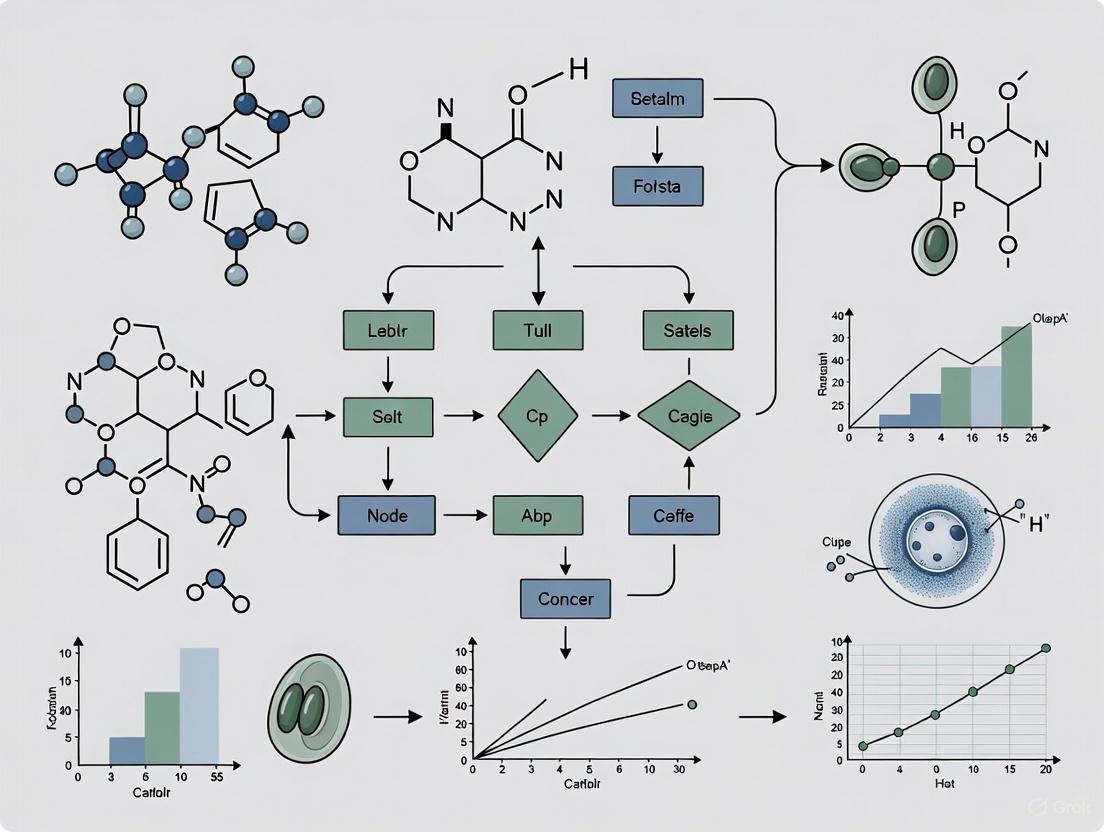

The following diagram illustrates the core logical workflow for identifying and correcting batch effects.

Guide 3: Experimental Design to Prevent Batch Effects

The most effective way to handle batch effects is to minimize them through careful experimental design.

Best Practices Protocol:

- Randomization: Never process all samples from one biological group together. Randomly assign samples from all groups (e.g., control and treated seeds) across your processing batches [3].

- Balancing: Ensure each batch contains a balanced representation of every biological condition and replicate in your study [5].

- Replication: Include technical replicates across different batches to help statistically model and account for technical noise [9].

- Standardization: Use consistent protocols, reagent lots, and equipment settings throughout the entire experiment where possible [4].

- Quality Control (QC) Samples: In metabolomics or proteomics studies, use pooled QC samples injected at regular intervals throughout the analytical run. These samples allow for modeling and correction of technical drift over time [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Managing Batch Effects

| Item / Solution | Function in Managing Batch Effects |

|---|---|

| Pooled Quality Control (QC) Samples | A homogenized pool of all study samples. Run repeatedly across batches to monitor technical performance and enable signal correction in mass spectrometry-based metabolomics/proteomics [9]. |

| Standardized Reagent Lots | Using the same lot number for all key reagents (e.g., enzymes for RNA extraction, sequencing kits) minimizes a major source of technical variation between batches [4]. |

| Reference Standards | Commercially available or in-house standards with known properties. Included in each batch to calibrate instruments and normalize measurements across runs. |

| Sample Tracking System | Robust metadata management (e.g., using a LIMS) to accurately record batch identifiers (lot numbers, dates, personnel) is essential for later statistical modeling and correction [2]. |

FAQ: Troubleshooting Batch Effects in Seed Experiments

Q1: My control and treated seed samples show dramatic transcriptional differences, but I'm concerned they are just batch effects. How can I tell? A1: This is a critical risk, especially if processing was not perfectly balanced. To diagnose:

- Visualize Clustering: Use Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or t-SNE plots colored by your experimental condition (e.g., control vs. drought) and by technical batch (e.g., processing date, sequencing run). If samples cluster more strongly by technical batch than by condition, batch effects are likely confounding your results [5] [10].

- Check for Confounding: In a perfectly balanced design, each batch contains an equal number of control and treated samples. If your treatment groups are completely separated by batch (e.g., all controls were processed on Monday, all treated on Tuesday), the study is "fully confounded" and it may be impossible to distinguish biological signal from technical noise [5].

- Validate with Biology: After batch correction, check if known biological expectations are met. For example, if studying drought recovery, ensure established recovery-specific genes are still correctly identified [11].

Q2: During seed production, does the environment the mother plant experiences create batch effects in the resulting seeds? A2: Yes, absolutely. The maternal environment is a potent source of what can be considered a biological batch effect. Seeds are not just genetic packages; they carry molecular imprints of their mother's environment, which can systematically alter the performance of your experimental seed batches [12].

- Common Effects: Maternal exposure to heat, drought, or nutrient stress can significantly alter seed dormancy, germination vigor, longevity, and stress tolerance in the offspring [12].

- Solution: Standardize and meticulously document the growth conditions for all mother plants. For critical experiments, produce all seeds for a single study in a synchronized growth cycle under tightly controlled environmental conditions to minimize this source of variation.

Q3: I am integrating transcriptomics and metabolomics data from developing seeds. What are the special batch effect risks in multi-omics studies? A3: Multi-omics integration multiplies the complexity of batch effects [10].

- Platform-Specific Noise: Each omics type (e.g., RNA-seq, LC-MS/MS for metabolites) has its own unique technical artifacts and noise profiles. When integrated, these can create false cross-layer correlations or obscure real ones [13].

- Solution: Model technical covariates for each data type separately before integration. Use methods designed for multi-omics data harmonization and always validate that known biological relationships between omics layers are preserved after correction [13] [10].

Q4: What is the most common mistake in experimental design that leads to irreparable batch effects? A4: The most critical mistake is a confounded study design, where the biological variable of interest (e.g., genotype A vs. genotype B) is perfectly correlated with a technical batch (e.g., all of genotype A was sequenced in Run 1, all of genotype B in Run 2). In this scenario, it is mathematically challenging, and often impossible, to determine whether observed differences are due to genetics or technical variation [5] [10]. Prevention is key: always randomize samples across technical processing batches.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Correcting Technical Batch Effects in Omics Data

This guide outlines a standard workflow for identifying and mitigating technical batch effects in seed omics studies (e.g., transcriptomics of germinating seeds).

- Objective: To remove unwanted technical variation from high-throughput datasets to reveal true biological signal.

- Principles: Batch effect correction (BEC) should reduce technical noise without removing biological variation of interest. Validation is essential [10].

Workflow Overview

Step-by-Step Protocol

Pre-Correction Diagnostics

- Action: Generate PCA or t-SNE plots of your data.

- How: Color the data points by known technical batches (e.g., sequencing run, extraction date) and separately by your experimental conditions (e.g., treatment, genotype).

- Interpretation: If samples cluster primarily by technical batch, you have a batch effect that needs correction [5] [10].

Assess Confounding

- Action: Examine your experimental design table.

- Interpretation: If your biological groups of interest are perfectly separated by a technical batch, your study is confounded. Statistical correction is risky and may remove biological signal. Results should be interpreted with extreme caution [5].

Apply Batch Effect Correction (BEC)

- Action: Choose and apply a BEC algorithm.

- Common Methods:

- Limma (

removeBatchEffect): A highly used linear model-based method [5]. - ComBat: Uses an empirical Bayes framework to adjust for batch effects [5] [13].

- Harmony: Often used for single-cell data but applicable elsewhere [13].

- SVA (Surrogate Variable Analysis): Useful when batch factors are unknown [5].

- Limma (

Post-Correction Validation

- Action: Repeat the visualization from Step 1 on the corrected data.

- Success Criteria:

Guide 2: Controlling for Maternal Environmental Effects in Seed Production

This guide provides strategies to minimize "biological batch effects" originating from the mother plant environment.

- Objective: To produce physiologically consistent seed batches by controlling pre-harvest environmental factors.

- Principles: The maternal environment acts as a natural priming signal, inducing transgenerational plasticity. Standardization is key to reproducibility [12].

Workflow Overview

Step-by-Step Protocol

Environmental Control

- Action: Grow maternal plants under highly controlled conditions.

- Protocol:

- Use climate-controlled growth chambers or greenhouses to maintain constant temperature, photoperiod, and light intensity.

- Standardize soil medium, pot size, and nutrient application.

- Implement a precise, automated watering system to avoid drought or waterlogging stress. Even mild, transient stress can alter seed traits [12] [11].

Synchronized Production

- Action: Minimize temporal variation during seed development.

- Protocol:

- Sow all mother plants for a single experiment simultaneously.

- For plants with indeterminate growth, synchronize flowering by hand-pollinating and tagging flowers on the same days. This ensures seeds at a given Days After Anthesis (DAA) are at equivalent developmental stages [14].

Standardized Harvest and Post-Harvest

- Action: Harvest seeds at a precise, biologically relevant stage.

- Protocol:

- Do not rely on days after anthesis (DAA) alone, as it can be variable. Use morphological markers (e.g., seed color, size) or physiological markers (e.g., seed dry weight plateaus) to define harvest time, as established in developmental studies [14].

- Process all harvested seeds with identical cleaning, drying, and storage protocols (temperature, humidity, duration).

Quantitative Data on Maternal Stress Effects

The table below summarizes how different maternal stresses can act as a systematic source of variation in seed batch performance, based on empirical evidence.

Table 1: Maternal Stress as a Source of Batch Effects in Seed Performance

| Maternal Stress | Species | Impact on Seed Batch (Offspring Phenotype) | Inheritance Scenario |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heat | Brassica napus (Oilseed Rape) | Increased germination time; decreased seed storage capacity [12]. | Intragenerational |

| Heat & Drought | Triticum durum (Durum Wheat) | Decreased germination rate and impaired early seedling growth [12]. | Inter/Intragenerational |

| Drought | Helianthus annuus (Sunflower) | Decreased seed dormancy; increased tolerance to low temperature and water stress during germination [12]. | Intragenerational |

| Drought | Glycine max (Soybean) | Reduced germination, seedling vigor, and seed quality in the next generation [12]. | Transgenerational |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for Managing Batch Effects in Seed Physiology Research

| Item / Reagent | Function in Experiment | Considerations for Batch Effect Control |

|---|---|---|

| Controlled-Environment Growth Chambers | Standardizes the maternal environment for seed production. | Critical for controlling temperature, light, and humidity variables that induce maternal effects [12] [14]. |

| Standardized Soil & Pots | Provides a uniform growth substrate for maternal plants. | Using the same soil batch and pot size minimizes variation in water and nutrient availability [12]. |

| RNA Stabilization Reagent (e.g., RNAlater) | Preserves RNA integrity at harvest for transcriptomics. | Use the same manufacturer and lot number for all samples to avoid reagent-based bias in RNA quality [10]. |

| Library Prep Kits for Sequencing | Prepares sequencing libraries from RNA or DNA. | Kit lot number is a major source of batch effects; using a single lot for an entire study is ideal [5] [10]. |

| Batch Effect Correction Software (e.g., Limma, ComBat) | Statistical correction of technical variation in omics data. | A tool of last resort; effective only when study design is not fully confounded. Choice of method depends on data type [5] [13] [10]. |

Understanding Batch Effects: The Silent Saboteurs

What are batch effects and how do they arise in plant physiology experiments?

Batch effects are systematic technical variations that are introduced during experimental processes rather than originating from true biological differences. In the context of plant physiology research, particularly in studies involving seed batches, these effects can arise from multiple sources throughout your experimental workflow [15] [5]:

- Different growth chambers or environmental conditions (temperature, humidity, light cycles)

- Variations in reagent lots or manufacturing batches, including growth media components

- Changes in sample preparation protocols across different time points

- Different personnel handling the samples or measurements

- Time-related factors when experiments span weeks or months

- Sequencing runs or instrumentation variations in omics studies

Why do batch effects matter specifically for seed physiology research?

The impact of batch effects extends to virtually all aspects of plant physiology data analysis [15]:

- Differential expression analysis may identify genes that differ between batches rather than between your experimental seed treatments

- Clustering algorithms might group samples by batch rather than by true biological similarity between seed varieties

- Pathway enrichment analysis could highlight technical artifacts instead of meaningful biological processes in seed development

- Meta-analyses combining data from multiple growing seasons or laboratories become particularly vulnerable

- Reproducibility crises emerge when batch effects confound real biological signals, leading to inconsistencies across studies [5]

Table: Common Sources of Batch Effects in Seed Physiology Research

| Source Category | Specific Examples in Seed Research | Impact Level |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental Conditions | Growth chamber variations, seasonal changes | High |

| Reagent Variations | Different lots of germination media, hormones | Medium to High |

| Technical Personnel | Multiple researchers handling measurements | Medium |

| Instrumentation | MS machines, sequencers, imaging systems | High |

| Temporal Factors | Experiments conducted on different days | Medium to High |

Detecting Batch Effects: Diagnostic Approaches

How can I identify batch effects in my seed experiment data?

Before attempting correction, it's crucial to assess whether batch effects exist in your data. Several visualization and quantitative approaches can help detect these technical variations [16]:

Visualization Methods:

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Perform PCA on your raw data and color-code by batch. Clustering by batch rather than biological condition indicates batch effects.

- t-SNE or UMAP: Overlay batch labels on these dimensionality reduction plots. In the presence of batch effects, samples from different batches tend to cluster separately.

- Heatmaps and dendrograms: Visualize whether samples cluster by batches instead of experimental treatments.

Quantitative Metrics: Several quantitative metrics can help identify batch effects with less human bias [16]:

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA)-based metrics

- Local Inverse Simpson's Index (LISI)

- Average Silhouette Width (ASW)

- k-Nearest Neighbor Batch Effect (kBET)

Table: Batch Effect Detection Methods for Plant Physiology Data

| Method | Best Use Case | Implementation Tools |

|---|---|---|

| PCA Visualization | Initial exploratory analysis | PRCOMP in R, scikit-learn in Python |

| t-SNE/UMAP | Non-linear batch effects | Seurat, Scanpy, scikit-learn |

| Clustering Analysis | Sample grouping patterns | Hierarchical clustering, heatmaps |

| Quantitative Metrics | Objective assessment | LISI, kBET, ASW packages |

Batch Effect Correction Strategies: Methodological Approaches

What are the main computational approaches for correcting batch effects?

There are two primary approaches to handling batch effects in experimental data [15]:

1. Correction Methods: These approaches transform your data to remove batch-related variation while preserving biological signals:

- Empirical Bayes methods (e.g., ComBat/ComBat-seq): Particularly useful for small sample sizes as they borrow information across genes or metabolites [15]

- Linear model adjustments: Remove estimated batch effects using linear regression techniques [15]

- Mixed linear models: Account for both fixed and random effects in your experimental design [15]

- Harmony and Seurat: Popular for single-cell data but applicable to other omics data types [16]

2. Statistical Modeling Approaches: Instead of directly transforming data, these incorporate batch information into statistical models:

- Including batch as a covariate: Common in differential expression analysis frameworks like DESeq2, edgeR, and limma [15]

- Surrogate variable analysis: Useful when batch information is incomplete or unknown [15]

Practical Implementation: Setting Up Your Correction Environment

Before implementing batch correction, set up your computational environment with necessary packages [15]:

How do I choose the right correction method for my seed physiology data?

Selection of appropriate batch correction methods depends on your experimental design and data characteristics [16]:

- For fully balanced designs where seed treatment groups are equally represented across batches, linear model approaches often work well

- For imbalanced designs where seed treatments are confounded with batches, more sophisticated methods like Harmony or mutual nearest neighbors (MNN) may be preferable

- When sample sizes are small, Empirical Bayes methods like ComBat are recommended as they borrow information across features

- For complex hierarchical designs (e.g., multiple growth chambers with sub-batches), mixed linear models can account for nested random effects

Batch Effect Correction Workflow for Seed Physiology Data

Experimental Design: Proactive Batch Effect Prevention

How can I design my seed experiments to minimize batch effects?

Proper experimental design is the most effective strategy for managing batch effects [5]:

- Implement balanced block designs where each batch contains representative samples from all experimental groups

- Randomize processing order of samples across different seed treatments and genotypes

- Include quality control samples (QCs) injected at regular intervals throughout your analytical runs [9]

- Replicate samples across batches to enable estimation and correction of batch effects

- Document all technical metadata including reagent lots, instrument settings, and environmental conditions

What is the critical consideration for sample imbalance in experimental design?

Sample imbalance occurs when there are differences in the number of cell types present, the number of cells per cell type, and cell type proportions across samples [16]. In seed physiology research, this could manifest as:

- Different numbers of seed varieties across growing batches

- Variations in replication numbers across treatment groups

- Unequal representation of mutant lines in different experimental blocks

Maan et al. (2024) benchmarked integration techniques across 2,600 integration experiments and found that "sample imbalance has substantial impacts on downstream analyses and the biological interpretation of integration results" [16]. This highlights that sample imbalance must be taken into consideration when designing experiments and integrating data.

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Batch Effect Management in Seed Physiology

| Reagent/Resource | Function in Batch Management | Implementation Tips |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Seed Samples | Internal controls across batches | Maintain identical seed stock from single source |

| Standardized Growth Media | Minimize nutritional variations | Use single large batch aliquoted for entire study |

| Quality Control Samples | Monitor technical variation | Include identical QC samples in each processing batch [9] |

| Sample Multiplexing | Reduce batch confounds | Process multiple seed treatments together using barcoding |

| Automated Protocols | Reduce personnel-based variation | Document and standardize all handling procedures |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Challenges and Solutions

Why might my batch correction be removing biological signals (over-correction)?

Over-correction occurs when batch effect removal algorithms inadvertently remove genuine biological variation. Signs of over-correction include [16]:

- Distinct seed varieties or treatments clustering together on dimensionality reduction plots

- Complete overlap of samples from very different conditions or experiments

- Cluster-specific markers comprised of genes with widespread high expression

- Loss of expected biological patterns that are well-established in literature

Solutions:

- Try a less aggressive correction method

- Adjust parameters to preserve more biological variation

- Validate with known biological markers that should remain differentiated

- Use negative controls that should not be affected by your experimental conditions

How should I handle non-detects or missing data in batch correction?

The strategy for handling non-detects (signals with intensity too low to be detected with certainty) is important in batch correction [9]:

- Avoid replacing with very small numbers like zero, as this can lead to suboptimal batch corrections [9]

- Use thresholding approaches based on detection limits

- Implement imputation methods designed for your specific data type (LC-MS, GC-MS, RNA-seq)

- Choose algorithms specifically designed to handle non-detects, as several approaches have been shown to handle them effectively [9]

FAQs: Addressing Common Researcher Questions

Q1: Should I always correct for batch effects in my seed physiology data?

Not necessarily. First assess whether batch effects exist and whether they are substantial enough to warrant correction. Minor technical variations that don't confound biological interpretations may not require aggressive correction. Always compare results with and without correction to ensure biological signals are preserved [16].

Q2: How many batches can I effectively correct for in my analysis?

The ability to correct for batch effects depends on your sample size and experimental design. As a general guideline, you should have multiple samples per batch and your biological conditions of interest should be represented across multiple batches. Correction becomes challenging with many batches and few samples per batch.

Yes, but with caution. When combining datasets from different sources or time periods, batch effects are almost inevitable. In such cases [5]:

- Apply appropriate batch correction methods

- Validate using known biological relationships that should persist across datasets

- Be transparent about the sources of variation in your combined dataset

- Consider using meta-analysis approaches rather than simple data merging

Q4: How does batch effect management support research reproducibility?

Proper batch effect management directly enhances research reproducibility by [17] [18]:

- Ensuring that technical artifacts don't lead to spurious biological conclusions

- Enabling other researchers to obtain similar results when following your methods

- Supporting methods reproducibility through detailed documentation of correction approaches

- Facilitating results reproducibility by removing technically-driven variations

- Strengthening inferential reproducibility by ensuring conclusions stem from biology rather than technical factors

Q5: What is the difference between reproducibility and replicability in this context?

These terms have specific meanings in scientific research [18] [19]:

- Repeatability: Same researchers, same methods, same conditions, same location

- Replicability: Different researchers, same methods, same conditions, different location

- Reproducibility: Different researchers, different methods and data, arriving at same results

Batch effect correction primarily supports reproducibility by ensuring that results hold true across different methodological approaches and technical conditions.

How Batch Effect Management Supports Research Reproducibility

Effective management of batch effects is not merely a technical preprocessing step but a fundamental component of rigorous plant physiology research. By understanding the sources of batch effects, implementing appropriate detection methods, applying reasoned correction strategies, and designing experiments to minimize technical variation, researchers can significantly enhance the data integrity and reproducibility of their seed physiology studies. The approaches outlined in this guide provide a comprehensive framework for addressing these challenges throughout the research lifecycle, from experimental design through data analysis and interpretation.

In plant physiology research, batch effects are technical variations introduced during experimental processes that are unrelated to the biological factors under study. These artifacts represent a paramount threat to data integrity, potentially leading to misleading outcomes, reduced statistical power, and irreproducible results [10]. In research on Phaseolus vulgaris (common bean) seed development—a cornerstone for global food security—addressing batch effects is particularly crucial due to the crop's importance as a major protein source and model for studying non-endospermic seed development [20] [21].

This technical support guide addresses batch effect challenges within the context of a broader thesis on reducing technical variability in plant physiology experiments. By integrating specialized protocols from Phaseolus vulgaris research with general principles of batch effect management, we provide researchers with actionable strategies to enhance the reliability of their seed development studies.

Understanding Batch Effects: Fundamentals for Researchers

What are batch effects and why are they problematic in seed development research?

Batch effects are systematic technical variations introduced into experimental data due to inconsistencies in sample processing, reagent lots, personnel, sequencing runs, or environmental conditions [3] [10]. In Phaseolus vulgaris seed research, where studies often track precise developmental stages from days after anthesis (DAA) through maturation, these technical variations can:

- Obscure true biological signals driving the transition from embryogenesis to seed filling [20]

- Complicate cross-study comparisons when different laboratories employ varying protocols [22]

- Lead to false conclusions about gene expression patterns during critical developmental windows [10]

How do batch effects specifically impact Phaseolus vulgaris seed development studies?

Research on Phaseolus vulgaris seed development involves precise morphological, histological, and transcriptomic analyses across defined developmental stages (e.g., 6, 10, 14, 18, and 20 DAA) [20]. Batch effects can significantly impact:

- Transcriptomic analyses attempting to identify genes upregulated during the transition to seed filling (typically between 10-14 DAA) [20]

- Histological assessments of storage compound accumulation in cotyledons [20]

- Morphological measurements of seed traits that correlate with later plant performance [23]

- Multi-omics integration efforts combining transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data [10]

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Diagnosing Batch Effects

How can I detect batch effects in my seed development dataset?

Visualization Methods:

- Perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and check if samples cluster primarily by batch rather than developmental stage or treatment condition [3] [10]

- Use UMAP plots to visualize high-dimensional data and identify technical clustering patterns [3]

- Create heatmaps of expression profiles to spot systematic variations correlated with processing batches

Quantitative Metrics:

- Average Silhouette Width (ASW): Measures how similar samples are to their own cluster compared to other clusters [3]

- Adjusted Rand Index (ARI): Assesses the similarity between batch-based clustering and biological condition clustering [3]

- Local Inverse Simpson's Index (LISI): Evaluates batch mixing while preserving biological variation [3]

- k-nearest neighbor Batch Effect Test (kBET): Tests whether batch labels are randomly distributed among nearest neighbors [3]

Table 1: Quantitative Metrics for Batch Effect Assessment

| Metric | Optimal Value | Interpretation | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| ASW | Close to 1 | Higher values indicate better separation of biological groups | General assessment of cluster quality |

| ARI | Close to 1 | Perfect agreement between biological and cluster labels | Evaluating clustering accuracy |

| LISI | Higher values | Better mixing of batches while preserving biology | Assessing integration quality |

| kBET | High p-values | Batches are well-mixed without significant differences | Testing batch null hypothesis |

Sample Preparation Variability:

- Differences in seed collection protocols across developmental timepoints [20]

- Variations in fixation methods for histological analysis (e.g., FAA fixative solution composition) [20]

- Inconsistencies in RNA extraction protocols across experimental batches [10]

Experimental Processing:

- Changes in reagent lots (e.g., different formaldehyde batches for histology) [20] [10]

- Variations in library preparation for transcriptomic studies [3]

- Differences in sequencing platforms or runs [3] [10]

Environmental and Personnel Factors:

- Storage conditions for seeds collected at different DAA timepoints [10]

- Personnel changes conducting sensitive histological procedures [20]

- Temporal variations when processing samples across multiple days [3]

Experimental Design Solutions: Preventing Batch Effects

How can I design my Phaseolus vulgaris experiment to minimize batch effects?

Randomization and Balancing:

- Randomize sample processing order rather than grouping all samples from the same developmental stage together

- Balance biological groups across processing batches to avoid confounding [3]

- Include replicates of each developmental stage within every batch [3]

Quality Control Integration:

- Incorporate quality control (QC) samples derived from a pooled reference sample across all developmental stages [9]

- Use technical replicates scattered across different batches to assess technical variability [3]

- Implement standardized protocols with detailed documentation for all procedures [10]

Practical Experimental Design Considerations for Phaseolus Research:

- When collecting seeds across multiple DAA timepoints (6, 10, 14, 18, 20 DAA), process samples from all timepoints in each batch rather than batching by developmental stage [20]

- For transcriptomic studies, extract RNA from all developmental stages using the same reagent lot and personnel [20]

- In multi-experiment studies, preserve portion of seeds from each developmental stage as reference material for cross-batch normalization

Batch Correction Methods: Computational Solutions

Which batch correction methods are most appropriate for seed development transcriptomics?

Table 2: Comparison of Batch Correction Methods for Transcriptomic Data

| Method | Strengths | Limitations | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Combat | Simple, widely used; adjusts known batch effects using empirical Bayes [3] | Requires known batch info; may not handle nonlinear effects [3] | Structured bulk RNA-seq data with defined batches [3] |

| SVA | Captures hidden batch effects; suitable when batch labels are unknown [3] | Risk of removing biological signal; requires careful modeling [3] | Complex experiments with partially unknown technical variation |

| limma removeBatchEffect | Efficient linear modeling; integrates with DE analysis workflows [3] | Assumes known, additive batch effect; less flexible [3] | Known batch variables with additive effects |

| Harmony | Aligns cells in shared embedding space; preserves biological variation [3] | Primarily designed for single-cell data | Single-cell or spatial RNA-seq data |

How do I validate batch correction success in my data?

Post-Correction Assessment:

- Visualize corrected data using PCA and UMAP to confirm samples now cluster by biological factors rather than batch [3]

- Calculate the same quantitative metrics (ASW, ARI, LISI, kBET) on corrected data and compare with pre-correction values [3]

- Verify that known biological patterns are preserved (e.g., gradual transcriptomic changes across DAA timepoints) [20]

Biological Validation:

- Confirm that established marker genes for specific developmental stages show expected expression patterns post-correction [20]

- Check that positive controls (genes known to be stable across development) remain consistent after correction

- Validate findings with alternative experimental methods when possible (e.g., confirm transcriptomic results with qPCR) [20]

Phaseolus vulgaris Specific Protocols: Minimizing Technical Variability

What specific protocols can reduce batch effects in Phaseolus seed histology?

Based on established methodologies for Phaseolus vulgaris seed development research [20]:

Standardized Fixation Protocol:

- Use consistent FAA fixative solution composition: 47.5% ethanol, 3.7% formaldehyde solution, 5% glacial acetic acid [20]

- Maintain precise fixation timing across all samples regardless of developmental stage

- Process biological replicates (recommended: n=4) for each timepoint simultaneously [20]

Sample Processing Consistency:

- Employ the same embedding and sectioning protocols across all experimental batches

- Use the same staining batches for all samples in a study

- Process reference control samples with each batch to monitor technical variability

How can I minimize batch effects in transcriptomic studies of seed development?

RNA Extraction and Library Preparation:

- Extract RNA from all developmental stages (6, 10, 14, 18, 20 DAA) using the same reagent lots [20]

- Process library preparation for all samples in randomized order within a short timeframe

- Include internal control RNAs to monitor technical variability across batches

Sequencing Considerations:

- Sequence samples from all developmental stages across multiple lanes/flow cells rather than batching stages together

- Balance sequencing depth across samples to avoid confounding with biological effects

- Include positive control samples with known expression profiles in each sequencing run

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Phaseolus Research

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Phaseolus vulgaris Seed Development Studies

| Reagent/Category | Function | Batch Effect Considerations | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| FAA Fixative [20] | Tissue preservation for histological analysis | Component ratios and fixation time significantly impact morphology | Prepare large master batch; document component sources and lots |

| RNA Extraction Kits | Nucleic acid isolation for transcriptomics | Different lots may vary in efficiency and purity | Use same kit lot for entire study; validate with QC metrics |

| Sequencing Kits | Library preparation for transcriptomics | Protocol variations affect coverage and bias | Balance library prep batches across biological conditions |

| Antibodies for Protein Analysis | Detection of specific seed storage proteins | Lot-to-lot variations in affinity and specificity | Validate each new lot with positive controls |

| Soil Composition [22] | Growth medium for plant cultivation | Nutritional variations affect seed development | Use consistent soil mix; document supplier and batch |

Special Considerations: Single-Cell and Multi-Omics Approaches

How do batch effect challenges differ in single-cell studies of seed development?

Recent advances in single-nuclei RNA sequencing of soybean seeds reveal that:

- The peripheral endosperm (PEN) shows the strongest drought response, with trajectory analysis revealing changes in PEN differentiation pathways under stress [24]

- Cell-type-specific responses to environmental stress can be obscured by batch effects [24]

- Integrated multi-omics approaches (snRNA-seq + snATAC-seq) require specialized batch correction strategies [24]

Recommended Approaches:

- Use Harmony or fastMNN specifically designed for single-cell data integration [3]

- Account for biological and technical zeros in sparse single-cell data [10]

- Perform cell-type-specific batch correction when appropriate for your research question

FAQs: Addressing Common Researcher Questions

Q1: What's the critical consideration when choosing between Combat and SVA for batch correction? A: Combat requires known batch labels and uses a Bayesian framework, while SVA estimates hidden variables representing batch-like effects. Choose Combat when you have clear batch information, and SVA when sources of technical variation are partially unknown [3].

Q2: Can batch correction accidentally remove true biological signal? A: Yes. Overcorrection may remove real biological variation if batch effects are correlated with the experimental condition. Always validate correction methods using positive controls with known biological patterns [3].

Q3: How many replicates per batch are needed for reliable batch effect correction? A: At least two replicates per group per batch is ideal. More batches allow more robust statistical modeling of technical variability [3].

Q4: In Phaseolus seed development studies, which developmental stages are most vulnerable to batch effects? A: Transition stages (e.g., 10-14 DAA when seeds shift from embryogenesis to maturation) are particularly vulnerable because subtle molecular changes can be obscured by technical variation [20].

Q5: What metrics best indicate successful batch correction? A: Visual clustering, replicate consistency, and quantitative scores like kBET, ARI, or silhouette width help assess correction success. Multiple metrics should be used together for comprehensive evaluation [3].

Visual Guides: Experimental Workflows and Decision Processes

Experimental workflow for batch-aware Phaseolus seed development research

Batch effect assessment and correction decision workflow

Successfully managing batch effects in Phaseolus vulgaris seed development research requires a comprehensive approach spanning experimental design, consistent protocols, appropriate computational correction, and rigorous validation. By implementing the strategies outlined in this technical guide—from standardized histological protocols to validated batch correction methods—researchers can significantly enhance the reliability, reproducibility, and biological relevance of their findings.

The integration of Phaseolus-specific methodologies with general batch effect principles provides a robust framework for advancing our understanding of legume seed biology while maintaining the highest standards of scientific rigor. As seed development research increasingly incorporates multi-omics approaches and single-cell technologies, proactive management of technical variability will remain essential for generating meaningful biological insights.

In plant physiology research, the integrity of experimental findings is paramount. Retracted studies and misleading conclusions not only impede scientific progress but also carry significant economic costs, wasting research funding, delaying product development, and misdirecting agricultural practices. A major, often-overlooked source of irreproducible results is the "seed batch effect"—undetected variations in seed quality, physiology, and performance between different seed lots of the same genotype. This technical support center provides targeted guidance to help researchers identify, troubleshoot, and mitigate these batch effects, thereby enhancing the reliability of their experimental outcomes.

FAQs: Understanding and Managing Seed Batch Effects

1. What is a seed batch effect, and why does it threaten my research? A seed batch effect refers to physiological differences between seed lots that can systematically bias your experimental results. These differences arise from variations in the maternal environment (e.g., growth temperature, light, nutrient status), storage conditions, and post-harvest aging. If unaccounted for, these effects can lead to misleading conclusions about genetic traits or treatment responses, ultimately threatening the validity and reproducibility of your research [23] [25].

2. How can I quickly screen a new seed batch for viability issues before starting a long experiment? Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) metabolomics offers a rapid, non-destructive method to predict seed germination capacity. This technique identifies metabolic biomarkers of aging, such as changes in sugars, amino acids, lactate, and dimethylamine. A multivariate analysis of the NMR profile can be used to build a model that accurately predicts the germination rate of a seed batch, allowing you to screen out low-viability lots before committing significant resources [26].

3. My seed germination is inconsistent. What are the primary factors I should check? Inconsistent germination is a classic symptom of batch effects. Your troubleshooting should focus on:

- Storage History: Document the age of the seed lot and its storage conditions (temperature and humidity). Seeds stored for long periods, even under optimal conditions, will naturally lose viability [26].

- Thermal Niche: Confirm that your germination temperature is within the optimal range for your species. For example, Inga jinicuil has an optimal germination temperature of ~31.5°C, with germination failing at near-ceiling temperatures of ~47°C [27].

- Seed Sizing: Sort your seeds by size. Studies in soybeans show that very small seeds have significantly lower germination potential, vigor, and subsequent plant performance compared to larger seeds from the same batch [25].

4. Can I "rescue" a low-performance seed batch for my experiment? Yes, seed priming is a technique that can improve the performance of sub-optimal seed batches. This pre-sowing treatment involves controlled hydration of seeds, which activates metabolic processes that repair damage and prepare for germination without allowing radicle protrusion. Methods like hydropriming, osmopriming, and hormonal priming can enhance germination synchrony and seedling vigor, potentially bringing a poorer batch up to an acceptable experimental standard [28].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Plant Growth and Morphology Despite Standardized Conditions

Potential Cause: Variability in seed vigor, mass, and physical traits between batches.

Solution Strategy: Implement High-Precision Seed Phenotyping.

- Action 1: Automate Individual Seed Analysis. Use automated systems like the phenoSeeder platform to phenotype individual seeds before sowing. This provides quantitative data on key traits for each seed [23].

- Action 2: Measure Critical Seed Traits. The following traits should be measured and recorded for correlation with later plant performance:

- Action 3: Correlate Seed and Plant Traits. Sow the phenotyped seeds and track corresponding plants using a system like Growscreen. This creates a dataset that can reveal, for example, if seed mass is positively correlated with early growth rate, allowing you to statistically control for this batch effect or exclude outliers [23].

Table 1: Key Seed Traits and Their Correlated Plant Performance Indicators

| Seed Trait | Measurement Method | Potential Impact on Plant Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Seed Mass/Volume | Automated balances, volume carving | Positive correlation with early growth rate and final dry matter accumulation [23] [25]. |

| Seed Color/Brightness | RGB imaging | Negative correlation with germination time; darker seeds may be associated with altered dormancy [23]. |

| Germination Time | Automated imaging (e.g., Growscreen) | May affect uniformity in subsequent developmental stages [23]. |

| Metabolic Profile | NMR Spectroscopy | Directly predictive of germination capacity and aging status [26]. |

Problem: Unpredictable Germination Rates in Critical Experiments

Potential Cause: Seed aging and deterioration during storage, leading to loss of viability.

Solution Strategy: Quantify Aging with Metabolic Biomarkers.

- Action 1: Conduct a Controlled Ageing Test. Subject a sub-sample of seeds to a controlled deterioration treatment (e.g., high temperature and humidity) to accelerate aging and amplify metabolic differences [26].

- Action 2: Perform NMR Metabolomic Analysis. Extract metabolites from fresh and artificially aged seeds and run 1H-NMR spectroscopy. This will generate a spectral profile of the seed's metabolome [26].

- Action 3: Identify Predictive Biomarkers. Use multivariate statistical models like Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (OPLS-DA) to identify metabolites that are significantly different between viable and aged seeds. Key biomarkers often include a decrease in glucose and an increase in lactate and dimethylamine [26].

- Action 4: Build a Prediction Model. Use a Partial Least Squares regression (PLS) model to correlate the metabolomic profile with actual germination rates. This model can then be used to predict the viability of unknown seed batches quickly [26].

The workflow below outlines this process from seed preparation to germination prediction.

Problem: Low Stress Resistance in Plants from a New Seed Batch

Potential Cause: The seed batch lacks adequate priming to activate defense pathways, a hidden batch effect related to the maternal environment.

Solution Strategy: Apply Seed Priming to Standardize and Enhance Baseline Resistance.

- Action 1: Select a Priming Agent. Choose an agent based on the stress you are studying:

- Abiotic Stress: Osmolytes like polyethylene glycol (PEG) or nutrients.

- Biotic Stress (Herbivory): Jasmonic Acid (JA) or Methyl Jasmonate (MeJA) to prime the JA defense pathway [28].

- Biotic Stress (Pathogens): Salicylic Acid (SA) or bio-priming with beneficial bacteria like Bacillus spp. to prime the SA pathway [28].

- Action 2: Execute the Priming Protocol.

- Imbibe seeds in a solution of the priming agent under controlled conditions.

- Incubate for a specific duration, ensuring the seeds do not progress to radicle emergence.

- Rinse and thoroughly dry the seeds back to their original moisture content.

- Action 3: Sow and Challenge. Sow the primed seeds and subject the plants to the intended stressor. Primed seeds will typically show a faster and stronger activation of defense mechanisms, such as the accumulation of defense proteins and secondary metabolites, leading to higher survival and performance [28].

The diagram below illustrates the seed priming process and its physiological effects.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Mitigating Seed Batch Effects

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Deuterated Solvent (D₂O) | Solvent for NMR-based metabolomics to assess seed batch quality [26]. | Required for locking and shimming during NMR spectroscopy. |

| Internal Standard (TSP) | Chemical reference standard (3-(Trimethylsilyl)propionic acid) for quantifying metabolites in NMR [26]. | Ensures accurate chemical shift referencing and quantification. |

| Jasmonic Acid (JA) / Salicylic Acid (SA) | Hormonal seed priming agents to standardize and boost biotic stress resistance pathways [28]. | Concentration is critical; too high can cause phytotoxicity, too low may be ineffective. |

| Mannitol/PEG Solutions | Osmoticums for creating controlled water deficit conditions during germination or priming assays [29] [28]. | Allows for precise manipulation of water potential to simulate drought stress. |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) | Treatment for microfluidic chips to maintain hydrophilicity, preventing surface-sensitive root growth issues in small plants [29]. | Critical for reproducible root phenotyping in lab-on-a-chip devices. |

| Enzyme Kits (HK/G6PD) | Enzymatic assay kits for quantitative biochemical analysis (e.g., starch content) in small tissue samples like seeds [29]. | Enables precise measurement of storage reserves that fuel germination. |

Practical Strategies: Experimental Design and Computational Correction Methods

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why do I get inconsistent results even when using seeds from the same species? Inconsistencies often arise from seed batch effects, which are variations due to factors like collection year, maternal environment, and storage conditions. For example, research on Ceiba aesculifolia seeds showed that batches collected in different years had significantly different germination rates and, more importantly, different transcriptional responses to a priming treatment, even when the seeds were at the same relative water content (RWC) [30]. This means physiological stage, not just time, is critical for comparison.

Q2: How can I minimize the impact of unknown variables in my plant physiology experiment? The core principle to achieve this is Randomization. Randomly allocating treatments to your experimental units (e.g., seeds, pots) helps average out the effects of uncontrolled or lurking variables. For instance, if you are testing a new seed treatment, randomizing which seeds receive the treatment prevents systematic biases from influencing your results [31] [32]. Without randomization, the effects of your treatment can become confounded with other environmental factors [32].

Q3: What is the difference between true replication and just taking multiple measurements? Replication involves applying the same treatment to multiple, independent experimental units. For example, having multiple pots of plants, each assigned to the same seed priming condition, constitutes a true replicate. Simply taking multiple measurements from the same plant is not true replication; it is pseudo-replication, as the measurements are not independent [32]. True replication allows you to quantify the natural variation in your experiment and increases the accuracy of your effect estimates [31].

Q4: My lab space is limited, and environmental conditions vary across the growth chamber. How can I account for this? This is a classic scenario for using a Blocking design. Instead of completely randomizing all treatments, you can group your experimental units into blocks based on the known nuisance factor (e.g., location in the growth chamber). Within each block, you then randomize all treatments. This controls for the variability between blocks, allowing for a more precise estimate of the treatment effect [32] [33]. For example, you might create a block for each shelf in your growth chamber.

Q5: Can seed priming help standardize performance across different seed batches? Yes, but its effectiveness can be batch-dependent. Seed priming is a pre-sowing technique that controls hydration to activate metabolic processes without radicle emergence [28]. However, studies on Ceiba aesculifolia identified "priming-responsive" (PR) and "non-responsive/negative" (NR) seed batches. NR batches showed no improvement or even a negative response to priming, highlighting that the inherent quality and history of the seed batch influence the success of standardization efforts [30].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Issue | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High variability in germination data within a treatment group. | Underlying genetic or physiological variation in the seed batch; inconsistent experimental conditions. | Increase replication to better capture and account for natural variation. Ensure strict environmental control and use a blocked design if variability is systematic [31] [32]. |

| Unable to distinguish treatment effect from environmental effect. | Confounding due to poor randomization. For example, all control plants are on one shelf and all treated plants on another. | Re-run the experiment with proper randomization of treatment assignments to all experimental units to break the link between treatment and lurking variables [32] [33]. |

| A priming treatment works in one lab but fails in another. | Unaccounted-for differences in seed batches (collection year, storage) or local environmental conditions. | Fully characterize seed batches (size, RWC, collection details). Use a balanced design that includes batch as a factor and report all batch metadata to improve reproducibility [30]. |

| Experiment results are statistically insignificant despite a visible trend. | Insufficient replication, leading to low statistical power to detect a true effect. | Conduct a power analysis before the experiment to determine the necessary sample size (number of replicates) to reliably detect the expected effect size [32]. |

| Seedling growth is uniformly poor across all treatments. | The seed batch itself may have low vigor or be unsuitable for the experiment. | Test seed viability and physiological potential before the main experiment. Sort seeds by size or weight, as these are often correlated with vigor [25]. |

Quantitative Data on Seed Batch Effects

The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from research that demonstrates the impact of seed batch variations on experimental outcomes.

Table 1: Impact of Seed Batch and Size on Physiological Performance

| Study Species / Material | Key Variable(s) Tested | Quantitative Findings & Observed Effects | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soybean (Kenfeng 16, Heinong 84) | Seed Size (Large, Medium, Small, Very Small) | Germination: Very small seeds had significantly lower germination potential, rate, and index. Growth: Plant height and leaf area decreased with seed size (Large > Medium > Small > VS). Yield: Number of pods and seeds per plant, and final yield, followed the same decreasing trend. [25] | |

| Ceiba aesculifolia (wild tree) | Seed Batch Collection Year & Priming Response | Seed batches from different years (e.g., 2012, 2014, 2015, 2016) showed significant differences in germination parameters and transcriptional profiles, regardless of imbibition time. Batches were classified as Priming-Responsive (PR) or Non-Responsive (NR). [30] | |

| Green Soybean Seeds | Brassinolide (BL) Conditioning | Seed conditioning with 0.6 μM Brassinolide improved vigor: increased root/shoot length and germination speed index. It also enhanced physiological performance, including gas exchange and chlorophyll a fluorescence. [34] |

Experimental Protocols for Reducing Batch Effects

Protocol 1: Standardized Seed Characterization and Sorting

This protocol is designed to homogenize experimental starting material and document batch-specific properties.

- Seed Sourcing and Documentation: Record the species, cultivar, source, collection year, and storage conditions (duration, temperature, humidity) for every seed batch.

- Size/Weight Sorting: Pass seeds through a series of sieves with defined pore sizes to separate them into uniform size categories (e.g., Large, Medium, Small). Alternatively, sort by seed weight [25].

- Viability Check: Perform a standard germination test (e.g., 50 seeds per replicate, on a moist sand or paper substrate) to determine the baseline germination percentage and vigor of the batch [25].

- Physiological Benchmarking: For some research questions, track the imbibition of individual seeds to determine a time-independent physiological trait, such as a specific Relative Water Content (RWC), which can be a more reliable stage marker than time-under-imbibition [30].

Protocol 2: Seed Hormopriming with Brassinolide

This protocol details a method to improve germination synchrony and vigor, potentially mitigating batch-to-batch differences in performance.

- Preparation of Solution: Prepare an aqueous solution of 0.6 μM Brassinolide (BL). A control treatment should use distilled water only [34].

- Imbibition: Imbibe the sorted, characterized seeds in the BL solution. The volume and duration should be determined empirically to allow hydration without radicle protrusion.

- Drying: After the imbibition period, dry the seeds back to their original moisture content under ambient conditions or with a controlled airflow.

- Sowing: Sow the primed seeds according to your experimental design, ensuring proper randomization and replication. The primed seeds should be compared against an unprimed control group.

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Seed Priming-Induced Stress Tolerance Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the key molecular pathways activated by various seed priming techniques, which contribute to improved germination and stress resilience.

Workflow for Batch-Effect Minimized Experiment

This workflow outlines the key steps for designing a robust plant physiology experiment that proactively accounts for seed batch effects.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents for Seed Physiology and Priming Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application in Experimental Design |

|---|---|

| Brassinolide (BL) | A plant steroid hormone used in hormopriming to improve seed germination, seedling vigor, and abiotic stress tolerance by regulating genes involved in growth and defense [34]. |

| Jasmonic Acid (JA) / Methyl Jasmonate (MeJA) | Phytohormones used as seed priming agents to induce herbivore resistance. They activate defense pathways leading to the production of defensive metabolites and volatiles [28]. |

| Salicylic Acid (SA) | A phytohormone used in seed priming to enhance resistance against biotic stressors like pathogens. It elevates the expression of defense-related genes such as chitinase and β-1,3-glucanases [28]. |

| Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂) | Used as a priming agent where calcium ions (Ca²⁺) act as secondary messengers. It can induce defense enzymes like lipoxygenase (LOX) and phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL), enhancing resistance against insects and pathogens [28]. |

| Sieves with Defined Pore Sizes | Essential for standardizing seed size across experimental units. Using seeds of uniform size reduces variability in germination and seedling growth, a major source of batch effects [25]. |

Longitudinal studies in plant physiology are essential for understanding developmental processes and environmental responses over time. However, their reliability is frequently compromised by technical variability and seed batch effects. These effects arise from inherent biological heterogeneity between seed batches, which can stem from maternal environmental conditions, harvesting times, and genetic factors. In Arabidopsis, for instance, even highly inbred lines exhibit variability in germination time, a bet-hedging strategy that ensures population survival in unpredictable environments but introduces significant noise into experiments [35]. This article establishes a technical framework for employing bridge samples and internal standards to mitigate these effects, ensuring data reproducibility and biological validity across extended experimental timelines.

Biological Basis of Seed Batch Effects

Seed batch effects are not merely technical artifacts; they are often rooted in adaptive plant biology. The phenomenon of bet-hedging describes a strategy where isogenic seeds from the same parent plant germinate at different times. This variability, while evolutionarily advantageous, presents a major challenge for experimental consistency. Research has demonstrated that this variability in germination time has a genetic basis and can function as a diversified bet-hedging strategy, ensuring that at least a fraction of a population survives unpredictable lethal stresses [35].

At the molecular level, single-cell transcriptional analyses of germinating Arabidopsis embryos reveal that most cells transition through a shared initial transcriptional state early in germination before adopting cell type-specific expression patterns [36]. This dynamic and coordinated process is sensitive to pre-existing molecular states in the seed, which can vary between batches.

Technical Variability in Analytical Measurements

In addition to biological variability, technical noise is introduced during sample processing and data acquisition. In metabolomics, for example, different analytical approaches (untargeted, semi-targeted, and targeted) have distinct characteristics and limitations regarding the number of metabolites detected and the level of quantification possible [37]. The table below summarizes these differences, which directly impact data quality in longitudinal studies.

Table 1: Characteristics of Analytical Methods in Metabolomics and Lipidomics

| Analysis Characteristic | Untargeted | Semi-Targeted | Targeted |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of metabolites typically detected | Hundreds or thousands | Tens or hundreds | One to tens |

| Level of quantification | (Normalised) chromatographic peak area; no absolute concentrations | Mix of peak areas and some absolute concentrations | Absolute concentration for all predefined metabolites |

| Metabolite identification | Structures of many metabolites unknown prior to assay; identification post-acquisition | Most metabolites known beforehand; some annotation post-acquisition | All metabolites known and confirmed before data collection |

| Biological bias | Lowest level of bias when multiple complementary assays are applied | Bias introduced as metabolites chosen based on standard availability | Bias introduced as a small number of pre-selected metabolites are measured |

The Quality Control Toolkit: Bridge Samples and Internal Standards

Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing a robust quality control system requires specific reagents and materials. The following table details key components.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Quality Control in Longitudinal Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Isotopically-Labelled Internal Standards | Compounds with stable isotopic labels (e.g., ^13^C, ^15^N) used for signal correction, normalization, and quantifying analyte recovery in targeted and semi-targeted assays [37]. |

| Authentic Chemical Standards | Pure, known quantities of target analytes used to construct calibration curves for absolute quantification in targeted assays [37]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Pool Sample | A homogeneous pool representing all biological samples in a study, repeatedly analyzed throughout the analytical run to monitor instrument stability and performance [37]. |

| DEA-NONOate | An NO donor used as a positive control for calibrating chemiluminescence-based Nitric Oxide detection, confirming the capability of the detection system [38]. |

| CPTIO | A Nitric Oxide scavenger used as a negative control to validate the specificity of the detected signal [38]. |

| Genetic Tools (e.g., nia1/nia2 mutants) | NO-deficient Arabidopsis mutants serving as biological negative controls for validating physiological responses like root growth or stomatal conductance [38]. |

What are Bridge Samples and Internal Standards?

Bridge Samples (also known as Quality Control samples or Reference samples) are a homogeneous pool of material that is aliquoted and analyzed repeatedly across multiple analytical batches or time points in a longitudinal study [37]. Their primary function is to monitor and correct for instrumental drift and procedural variability over time.

Internal Standards are known compounds added to each individual biological sample at a known concentration, typically before the extraction step. They are categorized as:

- Stable Isotope-Labeled Analogs: The gold standard, these are chemically identical to the target analyte but contain heavier isotopes, allowing them to be distinguished by mass spectrometry. They correct for extraction efficiency, matrix effects, and ion suppression [37].

- Structural or Chemical Analogs: Compounds with similar chemical structure to the analyte, used when isotope-labeled standards are unavailable (less ideal).

Experimental Protocol for Implementing a QC System

The following workflow diagram outlines the key steps for integrating bridge samples and internal standards into a longitudinal plant study.

Detailed Methodology:

Preparation of Bridge Samples (QC Pool):

- Source Material: Generate a large, homogeneous sample pool that is representative of the entire study. This could be a bulk harvest of plant tissue from the same genotype and condition used in the study, or a commercially available reference material.

- Homogenization: Process the material (e.g., grind frozen tissue) to ensure complete homogeneity.

- Aliquoting: Dispense the homogenized pool into single-use aliquots sufficient for the entire longitudinal study. Store all aliquots under identical, stable conditions (e.g., -80°C) to prevent degradation.

Use of Internal Standards:

- Selection: Choose stable isotope-labeled internal standards for each key analyte of interest. For untargeted studies, a cocktail of standards covering different chemical classes is used.

- Introduction: Add a fixed volume of the internal standard mixture to each experimental sample and each bridge sample aliquot prior to extraction. This ensures they undergo the entire sample preparation process.

Integration into Analytical Batches:

- In each analytical batch (e.g., each mass spectrometry sequence), include a set of experimental samples, several bridge sample aliquots (at beginning, middle, and end), and calibration standards.

- The repeated analysis of the bridge samples across batches allows for the creation of a correction model to adjust for systematic drift in the data.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: How many bridge samples should I include per analytical batch? A: A minimum of three to five bridge samples per batch is recommended. Place them at the beginning (to condition the system), evenly spaced throughout the run, and at the end to monitor drift over time.

Q2: My internal standard peak areas are highly variable in the bridge samples. What does this indicate? A: High variability in internal standard responses in the bridge samples suggests a problem with the instrument performance or sample preparation consistency, not the biological material. Investigate issues like injector carryover, deteriorating chromatography, or inconsistent pipetting during the sample preparation stage.

Q3: Can I use bridge samples to correct for biological seed batch effects? A: Bridge samples are primarily for correcting technical variation. While they cannot eliminate inherent biological differences between seed batches, a stable QC system gives you the confidence to distinguish true biological effects from technical noise. To address biological batch effects, ensure proper randomization of samples from different batches during analysis and consider including "batch" as a covariate in your statistical models.

Q4: What is an acceptable coefficient of variation (CV) for my metabolites in the bridge samples? A: A CV below 10-15% is generally considered acceptable for robust biological interpretation in metabolomics. A CV consistently above 20% indicates poor analytical precision and signals the need for protocol refinement or instrument maintenance [38].

Troubleshooting Common Scenarios

Scenario: A gradual drift in the peak areas of the bridge samples is observed over several weeks.

- Potential Cause: Instrumental drift, such as a loss of mass spectrometer sensitivity or degradation of the HPLC column.

- Solution: Use the data from the bridge samples to perform batch correction using statistical software. Ensure regular instrument maintenance and calibration.

Scenario: A sudden drop in the response of all internal standards in a single batch.

- Potential Cause: A preparation error in the internal standard mixture for that specific batch, or a major instrument fault.

- Solution: Re-prepare the internal standard solution and re-inject the affected samples if possible. Check instrument logs for errors.

Scenario: High biological variability in germination rates between seed batches is confounding my treatment effects.

- Potential Cause: This is a genuine biological batch effect, potentially linked to differences in dormancy status or maternal environment.