Troubleshooting Plant Protoplast Preparation for scRNA-seq: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust Single-Cell Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers navigating the challenges of plant protoplast preparation for single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq).

Troubleshooting Plant Protoplast Preparation for scRNA-seq: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust Single-Cell Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers navigating the challenges of plant protoplast preparation for single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq). It covers foundational principles of protoplast isolation, detailed methodological protocols for various plant species, systematic troubleshooting for common issues like viability and RNA integrity, and validation strategies to ensure data quality. By integrating the latest research, this guide offers practical solutions to overcome technical hurdles, enabling robust and reliable single-cell transcriptomic studies in plants for advanced developmental and biomedical applications.

Understanding Protoplast Biology and scRNA-seq Fundamentals

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is a plant protoplast and why is it important for single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq)? A plant protoplast is a living plant cell that has had its surrounding cell wall removed by enzymatic digestion, resulting in a "naked" cell bounded by the plasma membrane [1] [2]. These wall-less cells are crucial for plant scRNA-seq because this technology requires single-cell suspensions. The rigid cell wall of plants makes it impossible to create such suspensions without first converting cells into protoplasts [3] [4]. They serve as a versatile tool for functional genomics, including the study of gene expression at an unprecedented resolution, tracking developmental trajectories, and validating genome editing strategies [4] [5] [6].

Q2: My protoplast viability is low. What are the main factors affecting viability? Low protoplast viability can stem from several sources related to the isolation procedure. The developmental stage of the plant material is critical; overly young or old tissues often yield poor results. For cotton roots, the optimal window was found to be 65-75 hours after hydroponic culture [5]. The osmotic pressure of all solutions must be carefully maintained to prevent cell rupture or collapse; unbalanced osmotic pressure is a common cause of failure [1] [7]. Furthermore, long enzymatic digestion times can stress and damage cells. One study noted that cells left in a hypertonic enzyme solution for more than one hour failed to divide [7]. Finally, the presence of secondary metabolites like phenylpropanoids can reinforce cell walls and inhibit digestion, reducing yield and viability, particularly in woody species [8].

Q3: How can I quickly check the viability of my isolated protoplasts? Viability can be rapidly assessed using fluorescent stains and a microscope or cell counter. The most common method uses Fluorescein Diacetate (FDA), a non-fluorescent compound that freely penetrates cell membranes. In viable cells with intact membranes and active esterases, FDA is hydrolyzed to produce fluorescein, which emits bright green fluorescence [1] [2] [6]. Alternatively, Propidium Iodide (PI) or Evans Blue can be used. These dyes are excluded by intact plasma membranes but penetrate dead or damaged cells, staining them red or blue, respectively [2] [6]. A high-quality preparation for scRNA-seq should typically have viability exceeding 80% [5].

Q4: I am working with a recalcitrant woody species. Are there any special considerations? Yes, woody species like American elm often present additional challenges due to high levels of water-soluble phenolic compounds that can inhibit enzymatic cell wall degradation [8]. A novel approach to overcome this is to culture the source tissue in the presence of a Phenylalanine Ammonia Lyase (PAL) inhibitor, such as 2-Aminoindane-2-Phosphonic Acid (AIP). PAL is the first dedicated enzyme in the phenylpropanoid biosynthesis pathway. Inhibiting this pathway was shown to reduce tissue browning and increase protoplast isolation rates in American elm from 11.8% to 65.3% [8].

Q5: My protoplasts are not transfecting efficiently. How can I optimize this? Transfection efficiency in a PEG-mediated transformation depends on several factors. Research indicates that plasmid DNA concentration is a major influence, with efficiency increasing with purified plasmid amounts from 10 to 30 µg [6]. Furthermore, a heat-shock treatment post-transfection can increase the fluidity of the cell membrane, facilitating the absorption of exogenous DNA and boosting transformation rates to 60-70% [1]. Using smaller plasmid sizes also provides an advantage, as larger plasmids result in lower transfection efficiency [6].

Troubleshooting Common Protoplast Isolation Issues

Problem: Low Protoplast Yield

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Suboptimal plant material | Check the developmental stage and health of source tissue. | Use youthful, tender tissues. For roots, a specific developmental window (e.g., 3-day-old cotton taproots) is often ideal [5]. |

| Inefficient enzyme mixture | Test different concentrations and combinations of cellulase, macerozyme, and pectinase. | Systematically optimize enzyme ratios. A universal protocol suggests a two-step digestion with 1% cellulase, 0.5% pectinase, and 0.5% macerozyme [1]. |

| Inadequate digestion time | Microscopically monitor protoplast release over time. | Extend digestion time with gentle shaking. For some species, a secondary digestion step can increase yield [1]. |

| Inhibitory compounds | Observe if the tissue or enzyme solution turns brown. | For woody species, add a PAL inhibitor (e.g., AIP) to the culture medium pre-isolation [8]. Pre-wash tissues thoroughly to remove water-soluble inhibitors [8]. |

Problem: Poor Protoplast Viability

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Improper osmoticum | Measure the osmolarity of all solutions. | Adjust the concentration of osmotic stabilizers (e.g., mannitol, sorbitol) to match the isotonic level of the tissue. 0.6 M mannitol was optimal for rice [6]. |

| Excessive digestion | Perform a time-lapse viability assay (e.g., with FDA). | Reduce digestion time. Include a purification step using a sucrose gradient to separate viable from non-viable protoplasts [6]. |

| Physical damage | Check for overly vigorous shaking or pipetting. | Handle protoplasts gently. Use wide-bore pipette tips. Centrifuge at low g-forces (e.g., 50-100 g) for short durations [5]. |

| Solution contaminants | Ensure all solutions are sterile and free of particulates. | Filter-sterilize enzyme and washing solutions using 0.2-0.45 μm filters [2] [5]. |

Problem: Protoplasts Not Dividing in Culture

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low initial viability | Re-check viability at the time of culture plating. | Ensure the viability is >80% before culture. Use a density of 1-2 x 10^5 protoplasts/mL for culture [2]. |

| Suboptimal culture medium | Test different basal media and hormone combinations. | Use a specialized protoplast culture medium, such as KM medium, supplemented with appropriate plant growth regulators like 2,4-D [2]. |

| Osmotic stress in culture | Monitor for protoplast bursting or shrinkage. | Maintain correct osmotic pressure in the culture medium. Gradually reduce osmolarity in subsequent feeding media [2]. |

| Prolonged enzyme exposure | Review the total time in enzyme solution. | Minimize the time protoplasts spend in the enzyme mix, as prolonged exposure can cause irreversible stress [7]. |

Quantitative Data for Protoplast Isolation and Transfection

Table 1: Optimized Enzyme Combinations for Different Plant Materials

This table summarizes successful enzyme formulations reported for various species and tissues, serving as a starting point for protocol development.

| Plant Species | Tissue | Cellulase (%) | Macerozyme (%) | Pectinase (%) | Yield & Viability | Citation Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chirita pumila | Leaf Mesophyll | 1.0% | 0.5% | 0.5% | Highest yield (6.8 x 10^5 cells/gFW); Viability ~92% | [1] |

| Cotton (G. hirsutum) | Taproot | 1.5% | 0.75% | - | Yield 3.55 x 10^5/g; Viability 93.3% | [5] |

| Wheat | Mesophyll | 1.5% | 0.75% | - | Initiated cell division in 8 days | [2] |

| Tobacco | Leaf | 1.5% | 0.5% | - | Suitable for scRNA-seq (7,740 cells captured) | [9] |

| American Elm | Callus (with AIP) | 0.2% RS + Driselase | - | 0.03% Y23 | Isolation rate increased from 11.8% to 65.3% | [8] |

Table 2: Parameters for High-Efficiency Protoplast Transfection

Optimizing transfection is key for applications like CRISPR vector validation. The data below from a cross-species study provides a benchmark.

| Parameter | Optimal Condition (Rice) | Optimal Condition (Arabidopsis) | Impact on Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmid DNA Amount | 20-30 µg | 20-30 µg | Increased efficiency from 55% to 80% in rice [6] |

| Transfection Duration | 20 minutes | 20 minutes | Highest efficiency observed at 20 min incubation [6] |

| Plasmid Size | ~10 kb plasmid | ~10 kb plasmid | Smaller plasmids had a significant advantage over larger ones [6] |

| Ca2+ Concentration | 200 mM | 200 mM | Crucial for achieving high (80%) transfection efficiency in cotton [5] |

| Protopost Viability | >80% (with sucrose gradient) | >76% (with sucrose gradient) | Sucrose gradient step dramatically improved viable yield and subsequent transfection [6] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Example & Note |

|---|---|---|

| Cellulase R10 | Hydrolyzes cellulose, the primary structural component of the plant cell wall. | Often used in combination with Macerozyme. Concentrations typically range from 1% to 1.5% (w/v) [2] [5]. |

| Macerozyme R10 | Degrades pectins in the middle lamella, which holds adjacent plant cells together. | Essential for tissue dissociation. Common concentrations are 0.5% to 0.75% (w/v) [2] [5]. |

| Pectinase | Specifically targets and breaks down pectin polysaccharides. | Can be a critical additive for some species. Was a key component in the universal Chirita pumila protocol [1]. |

| Osmotic Stabilizers (Mannitol/Sorbitol) | Create an isotonic environment to prevent the fragile protoplasts from bursting due to osmotic pressure. | Commonly used at 0.4 M to 0.6 M. Concentration must be optimized for each species/tissue [5] [6]. |

| PAL Inhibitors (e.g., AIP) | Inhibits phenylalanine ammonia lyase, reducing the synthesis of phenolic compounds that inhibit cell wall digestion. | Particularly useful for recalcitrant species like American elm. Used at 10-150 µM in culture medium pre-isolation [8]. |

| PEG (Polyethylene Glycol) | Facilitates the delivery of foreign DNA, RNA, or proteins into protoplasts by promoting membrane fusion. | The most common method for protoplast transfection. Used in a PEG-Ca2+ solution [1] [6]. |

| Fluorescein Diacetate (FDA) | A viability stain that is metabolized by active esterases in live cells to produce a green fluorescent product. | Allows for rapid quantification of viable protoplasts before proceeding to expensive downstream applications [2] [6]. |

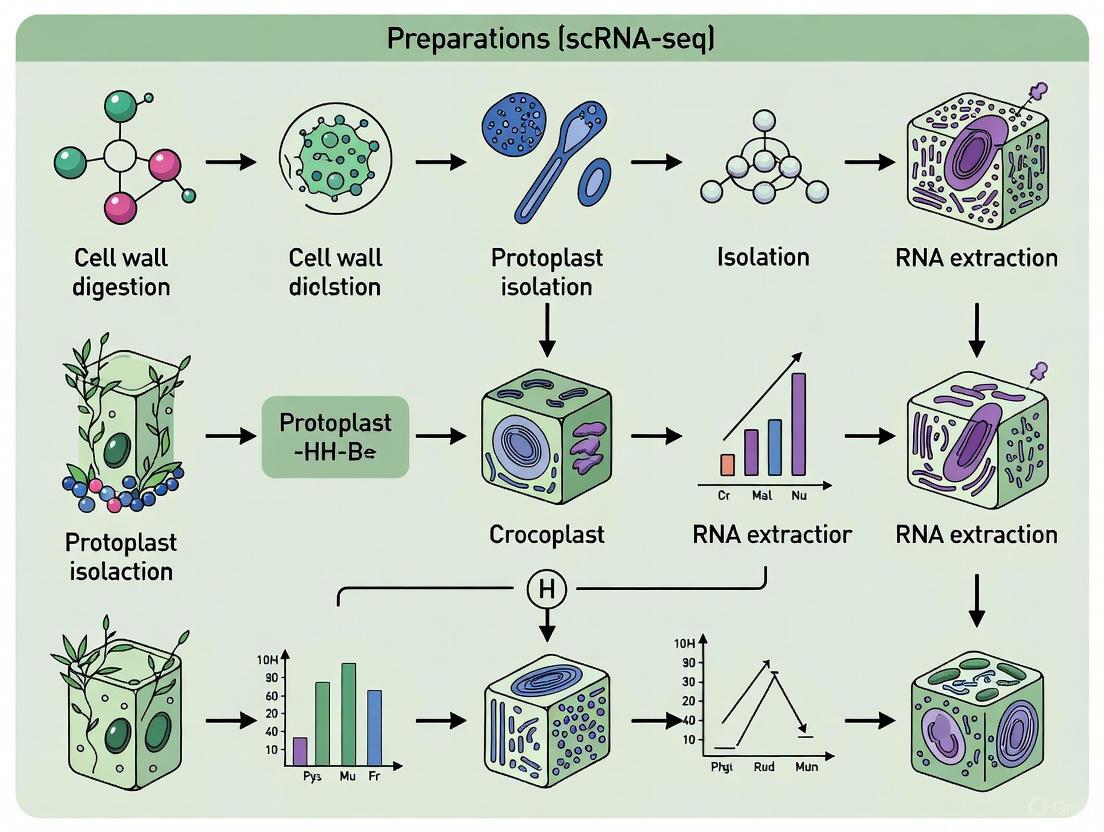

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Protoplast to scRNA-seq Workflow

Troubleshooting Low Yield Pathway

The Critical Role of Protoplasts in Accessing Single-Cell Transcriptomes

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized plant biology by allowing researchers to investigate cellular heterogeneity and gene expression at an unprecedented resolution. Protoplasts, which are plant cells that have had their cell walls enzymatically removed, serve as a primary starting material for these studies. This technical support center addresses the most common challenges and questions researchers face when preparing protoplasts for scRNA-seq, providing troubleshooting guides and detailed protocols to ensure successful experimental outcomes.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the primary advantage of using protoplasts over nuclei for scRNA-seq in plants? Protoplasts provide a more holistic view of the transcriptome because they capture both nuclear and cytoplasmic RNAs. This comprehensive capture allows for a fuller picture of gene expression patterns and regulatory processes within individual cells [4].

2. What is the major drawback of protoplast isolation, and what is a common alternative? A significant drawback is the "transcriptomic shock" or cellular stress induced by the enzymatic digestion process, which can alter gene expression profiles. A common alternative is using isolated nuclei for single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq), which minimizes this stress and can provide better recovery of cell types that are difficult to protoplast [10] [4].

3. Why might my protoplast sample lack certain cell types? Different cell types have varying sensitivities to cell wall-degrading enzymes and possess different wall structures, leading to skewed distributions in the final protoplast suspension. For instance, protoplasting of maize leaves has been known to fail in recovering vascular cells [10].

4. How can I improve the viability of my isolated protoplasts? Viability can be optimized by carefully tuning the enzyme solution. For example, in cabbage, a dramatic decrease in viability (from 97% to 37%) was observed when the concentration of Pectolyase Y-23 was increased from 0.05% to 0.1%. Substituting with 0.1% Macerozyme R-10 resulted in high yields while maintaining viability over 90% [11].

5. Can I use frozen tissue for protoplast isolation? Typically, no. Protoplast isolation generally requires fresh tissue, as the enzymatic digestion process is performed on living cells. In contrast, nuclei can be isolated from frozen or fixed tissue, which is a key advantage of the snRNA-seq approach [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Protoplast Yield

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Suboptimal enzyme concentration or combination.

- Cause: Inadequate digestion time.

- Solution: Optimize the duration of enzymatic digestion. While some tissues like tobacco may digest in 4 hours, others like celery may require 8 hours or more [12].

- Cause: Incorrect osmotic pressure in the enzyme solution.

- Solution: Adjust the concentration of an osmoticum like mannitol. A concentration of 0.6 M was found to be optimal for celery protoplast isolation [12].

Problem: Poor Protoplast Viability

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Over-digestion with overly concentrated enzymes, particularly pectinases.

- Solution: Reduce the concentration of pectolytic enzymes. As noted in the cabbage study, high Pectolyase Y-23 concentration (0.1%) severely compromised viability [11].

- Cause: Damage during purification.

- Solution: Use gentle centrifugation speeds. For celery, 200× g was optimal for collecting protoplasts without causing damage [12]. Always use a sucrose or percoll gradient for gentle purification.

- Cause: Oxidative stress after isolation.

- Solution: Include antioxidants in the culture media. Research on cannabis protoplasts has shown that cultured cells exhibit oxidative stress resilience, which is crucial for viability [13].

Problem: Skewed Cell Type Representation in scRNA-seq Data

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Inherent bias in the protoplasting efficiency of different cell types.

- Cause: Over-representation of easily digestible cell types like mesophyll.

- Solution: Use mechanical methods to pre-expose harder-to-digest tissues. For example, scraping the bark off poplar stems or using a "tape sandwich" to remove epidermal layers in Arabidopsis leaves can facilitate protoplast release from underlying tissues [10].

Optimized Experimental Protocols

Sample Preparation: Isolation of Leaf Mesophyll Protoplasts

The following table summarizes optimized enzyme solutions for different plant species, demonstrating that protocols must be species-specific.

Table 1: Optimized Enzyme Solutions for Protoplast Isolation from Various Plant Species

| Plant Species | Cellulase Concentration | Pectinase Concentration | Osmoticum (Mannitol) | Digestion Time | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cabbage (Brassica oleracea) | 0.5% Cellulase Onozuka RS | 0.1% Macerozyme R-10 | Information Missing | Overnight | [11] |

| Celery (Apium graveolens) | 2.0% Cellulase R-10 | 0.1% Pectolase | 0.6 M | 8 hours | [12] |

| Moss (Physcomitrella patens) | Protocol described | Protocol described | Information Missing | Information Missing | [14] |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | 1.5% Cellulase | 0.4% Pectolase | Information Missing | Information Missing | [12] |

Detailed Protocol for Celery Protoplast Isolation [12]:

- Plant Material: Use leaves from 3-week-old, sterile-grown celery seedlings.

- Tissue Preparation: Slice leaves into very fine strips (0.5–1 mm width) using a sharp blade.

- Enzymatic Digestion: Immerse the leaf strips in the filter-sterilized enzyme solution (2.0% cellulase, 0.1% pectolase, 0.6 M mannitol, pH 5.8).

- Incubation: Incubate in the dark at 25°C with gentle shaking (45 rpm) for 8 hours.

- Purification:

- Filter the resulting protoplast suspension through a 400-mesh sieve to remove undigested debris.

- Centrifuge the filtrate at 200× g to pellet the intact protoplasts.

- Resuspend the pellet in a W5 salt solution (2 mM MES, 154 mM NaCl, 125 mM CaCl₂, 5 mM KCl; pH 5.7).

- Assessment: Count protoplasts using a hemocytometer and assess viability (should be >90%) using FDA staining.

Workflow for scRNA-seq Library Construction

The following diagram illustrates the general workflow for proceeding from plant tissue to scRNA-seq data, highlighting critical steps where troubleshooting is often required.

Method Selection: Protoplasts vs. Nuclei

Choosing between protoplasts and nuclei is a critical first step in experimental design. The following table compares these two primary methods to guide researchers.

Table 2: Comparison of Protoplast-based and Nucleus-based Methods for Plant scRNA-seq

| Feature | Protoplast-based scRNA-seq | Nucleus-based snRNA-seq |

|---|---|---|

| Transcriptome Coverage | Captures nuclear and cytoplasmic RNA (full transcriptome) [4] | Primarily captures nuclear RNA; misses cytoplasmic transcripts [4] |

| Cellular Stress | High ("transcriptomic shock" from 1-2 hour digestion) [10] | Low; minimal perturbation [10] |

| Cell Type Bias | High; some cell types (e.g., vasculature) are difficult to isolate [10] | Lower; better recovery of hard-to-dissociate cell types [4] |

| Sample Flexibility | Requires fresh tissue [10] | Compatible with frozen or fixed tissue [10] [4] |

| Ideal Use Case | Studies requiring full transcriptome data from easily protoplasted tissues (e.g., mesophyll) | Studies of complex tissues, rare cell types, or when sampling requires preservation |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Protoplast Isolation and scRNA-seq

| Reagent | Function | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Wall-Digesting Enzymes | Break down cellulose (cellulase) and pectin (pectinase) in the plant cell wall. | Cellulase Onozuka RS, Macerozyme R-10, Pectolyase Y-23 [11] [12] |

| Osmoticum | Maintains osmotic pressure to prevent protoplast bursting. | Mannitol (0.4 - 0.7 M) [12] |

| Viability Stain | Assesses the health and integrity of isolated protoplasts. | Fluorescein Diacetate (FDA) [12] |

| Purification Sieve | Removes undigested tissue and debris from the protoplast suspension. | 400-mesh sieve [12] |

| scRNA-seq Library Kit | For barcoding, reverse transcription, and library construction of single-cell transcripts. | 10x Genomics Chromium Single Cell 3' Reagent Kits [14] [4] |

| Protoplast Culture Medium | Supports protoplast regeneration and cell division for downstream applications. | Modified MS or KM media with plant growth regulators [13] |

Successful single-cell transcriptomics in plants hinges on robust protoplast preparation. While challenges such as cellular stress, low yield, and cell type bias persist, they can be overcome with careful optimization of enzymatic cocktails, digestion conditions, and purification methods. By understanding the trade-offs between protoplast and nucleus isolation, and by applying the troubleshooting guidelines presented here, researchers can reliably generate high-quality single-cell suspensions to unlock the cellular heterogeneity of plants.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary challenges when preparing plant protoplasts for single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq)?

The three most significant challenges are:

- Cellular Heterogeneity: Tissues consist of many different cell types. A successful protoplast isolation must capture this full diversity without introducing bias towards or against any specific cell type [3] [15].

- Cell Wall Digestion: The plant cell wall is a complex, rigid structure that varies between species, organs, and developmental stages. Incomplete digestion yields low protoplast numbers, while over-digestion can damage cells and induce stress responses, compromising viability and transcriptomic data [16] [1] [17].

- Transcriptional Stress: The protoplast isolation process itself—involving enzymatic digestion, mechanical stress, and changes in osmotic pressure—can trigger rapid and significant changes in gene expression. This makes it difficult to distinguish true biological signals from technical artifacts [3] [1].

FAQ 2: Should I use protoplasts (whole cells) or nuclei for plant scRNA-seq?

The choice depends on your research question and plant material. The table below compares the two approaches.

Table 1: Comparison of Protoplasts vs. Nuclei for scRNA-seq

| Feature | Protoplasts (Whole Cell) | Nuclei (snRNA-seq) |

|---|---|---|

| Transcriptome Coverage | Captures both nuclear and cytoplasmic mRNA, providing a more complete picture of the transcriptome [18]. | Primarily captures nuclear transcripts; may miss some cytoplasmic mRNAs [3] [18]. |

| Applicability | Ideal for tissues with cells that are easily dissociated and have thin walls (e.g., young leaves, roots) [16] [5]. | Essential for tissues that are difficult to dissociate (e.g., woody tissues, fibrous tissues) or when cells are exceptionally large [3] [16] [18]. |

| Stress Response | High risk of inducing transcriptional stress responses during cell wall digestion [16] [1]. | Minimizes stress associated with cell wall digestion, as nuclei can be isolated from frozen tissue, "freezing" the transcriptional state [3] [18]. |

| Spatial Information | Like nuclei, protoplasts lose their native spatial context within the tissue upon isolation [3]. | Loses native spatial context, though spatial transcriptomics techniques can compensate for this [3] [19]. |

FAQ 3: How can I minimize transcriptional stress during protoplast isolation?

Minimizing stress requires a optimized and gentle protocol:

- Optimize Digestion Time: Use the shortest effective digestion time to avoid prolonged stress [20] [5].

- Control Temperature: Perform all steps, especially after digestion, at 4°C to arrest cellular metabolism and reduce stress-related gene expression [18].

- Use Proper Osmotic Stabilizers: Maintain correct osmotic pressure with substances like mannitol or sorbitol to prevent cell lysis or rupture [20] [17].

- Work Quickly: Process samples rapidly from isolation to sequencing or fixation to capture an accurate transcriptional snapshot [18].

FAQ 4: What is a critical step often overlooked in protoplast regeneration for genome editing?

A key step is the inclusion of mycelial extract or other tissue-specific extracts in the regeneration medium. For example, adding Lyophyllum decastes mycelial extract to the Z5 medium significantly increased the regeneration rate to 2.86 [20]. This suggests that species-specific supplements providing essential growth factors can dramatically improve the efficiency of regenerating whole plants from transfected protoplasts.

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Low Protoplast Yield and Viability

Table 2: Troubleshooting Protoplast Isolation

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Yield | Inefficient enzyme solution | Systematically optimize enzyme concentrations and combinations (cellulase, macerozyme, pectinase). A two-step digestion process can also improve yield [1]. |

| Suboptimal plant material | Use young, actively growing tissues (e.g., 65-75 hour hydroponically grown cotton roots, 10-day-old fungal mycelia). Older tissues have thicker, more recalcitrant cell walls [20] [5]. | |

| Incomplete tissue digestion | Cut tissue into fine, translucent slices to maximize surface area for enzyme action [5]. | |

| Low Viability (<80%) | Over-digestion | Reduce enzymatic digestion time. Conduct time-lapse experiments to find the optimal window [20] [1]. |

| Osmotic shock | Ensure the osmotic stabilizer (e.g., 0.6M mannitol, MgSO₄) is present in all solutions and is appropriate for your species [20] [5]. | |

| Mechanical damage | Avoid vigorous pipetting or shaking. Use wide-bore pipette tips and round-bottom centrifuge tubes [5] [18]. | |

| High Debris & Clumping | Presence of dead cells and cations | Use calcium- and magnesium-free buffers. Filter the protoplast suspension through a 30-40 μm cell strainer and use density gradient centrifugation to remove debris [19] [18]. |

Addressing Cellular Heterogeneity in scRNA-seq Data

Table 3: Optimizing for Cellular Heterogeneity

| Challenge | Impact on Heterogeneity | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Size-Based Bias | Droplet-based systems may under-sample large cells [5]. | For large cells, use nuclei (snRNA-seq) or employ a plate-based scRNA-seq platform that is less sensitive to cell size [16] [18]. |

| Rare Cell Types | Rare cell populations may be missed due to insufficient cell numbers [19] [15]. | Sequence a sufficiently high number of cells. For complex tissues, target tens of thousands of cells to ensure rare types are captured [5] [18]. |

| Batch Effects | Technical variation between samples can confound biological differences [19]. | Use combinatorial barcoding to process multiple samples in a single run [15] [18]. Employ batch correction algorithms (e.g., Harmony, Combat) in downstream analysis [19]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Protoplast Work

| Reagent / Material | Function | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cellulase R10 | Hydrolyzes cellulose, the primary structural component of the plant cell wall. | A standard enzyme for protoplast isolation; often used at 1.5-2% (w/v) concentration [5] [17]. |

| Macerozyme R10 | A mixture of enzymes that targets pectin in the middle lamella, helping to separate cells. | Typically used at 0.2-0.75% (w/v) [1] [5]. |

| Pectinase | Specifically degrades pectin, crucial for breaking down the cell wall matrix. | Concentration must be optimized; used at 0.5% in some protocols [1]. |

| Osmotic Stabilizer | Prevents protoplast lysis by maintaining osmotic balance. | Mannitol (0.4-0.6 M) is most common. Sorbitol, sucrose, or KCl can also be used [20] [5] [17]. |

| Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂) | Stabilizes the plasma membrane and facilitates protoplast fusion and transfection. | Used in washing solutions (e.g., W5 solution) and to enhance PEG-mediated transfection [5] [17]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Facilitates the delivery of DNA, RNA, or proteins (like CRISPR RNP) into protoplasts. | PEG 4000 at 40% concentration is standard, but heat shock treatment can further increase efficiency [1] [17]. |

| Miracloth / Cell Strainer | Filters out undigested tissue debris and cell clumps to create a clean protoplast suspension. | Use multiple layers of Miracloth followed by a 30-40 μm nylon mesh strainer [20] [5]. |

Experimental Workflow and Decision Diagrams

Diagram 1: Protoplast Experimental Planning

Diagram 2: Optimal Protoplast Workflow

Within the broader context of troubleshooting plant protoplast preparation for single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), a fundamental decision researchers face is the choice of biological starting material. The two primary entities used are protoplasts (whole cells with their walls enzymatically removed) and isolated nuclei (for single-nucleus RNA-seq, or snRNA-seq). This guide details the technical trade-offs between these approaches to help you select the optimal strategy for your experimental goals and sample type, and to troubleshoot common pitfalls associated with plant sample preparation [4] [21].

The following workflow outlines the critical decision points and associated challenges for each path:

Technical Comparison Table

The choice between protoplasts and nuclei involves a direct trade-off between transcriptome completeness and the minimization of technical artifacts. The following table summarizes the core technical differences:

| Feature | Protoplasts | Single Nuclei |

|---|---|---|

| Transcriptome Coverage | Full transcriptome (nuclear + cytoplasmic) [4] | Nuclear transcriptome; loss of cytoplasmic mRNAs [4] |

| Sample Preparation Impact | Enzymatic digestion induces cellular stress & alters gene expression [4] [21] | Minimal perturbation; no cell wall digestion needed [4] [21] |

| Tissue Applicability | Limited by digestibility; recalcitrant tissues (e.g., xylem) are challenging [4] [5] | Broad applicability; suitable for hard-to-digest tissues & frozen samples [4] [21] |

| Cell Size Restrictions | Yes; must be <40-50 µm for droplet-based platforms (e.g., 10x Genomics) [5] | Minimal constraint; nuclei are small and uniform [21] |

| Key Advantage | Captures a more complete picture of cellular gene expression. | Better preserves native transcriptional states; wider tissue applicability. |

| Major Limitation | Stress responses can confound biological interpretations. | Incomplete transcriptome limits analysis of cytoplasmic processes. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

How do I decide whether to use protoplasts or nuclei for my experiment?

Your choice should be guided by your research question and sample type.

- Choose Protoplasts if: Your biological question involves signaling pathways, metabolic activity, or other processes reliant on cytoplasmic mRNA, and you are working with a tissue that is known to be easily digestible (e.g., young Arabidopsis or cotton roots) [4] [5].

- Choose Nuclei if: You are working with recalcitrant tissues (e.g., woody tissues, xylem), studying nuclear-specific processes like transcription, or are concerned that enzymatic stress will mask your biological signal of interest [4] [21]. Nuclei are also the preferred option when working with archived or frozen samples [4].

I am getting low protoplast yield and viability. How can I improve this?

Low yield and viability are often related to the starting plant material and digestion protocol.

- Optimize Plant Material: The developmental stage is critical. Use youthful and tender tissues. For cotton roots, the optimal window is 65-75 hours after hydroponic culture [5].

- Optimize Enzyme Solution: Fine-tune the concentration of cellulase and macerozyme enzymes. A common starting point is 1.5% Cellulase R10 and 0.75% Macerozyme R10 in an osmoticum like 0.4-0.5 M mannitol [5] [22].

- Control Digestion Conditions: Limit digestion time (typically 3-4 hours) and use gentle shaking (40-50 rpm) to prevent mechanical stress [5].

My protoplasts are clustering during scRNA-seq, suggesting a stress response. How can I mitigate this?

This is a known limitation of protoplasts. To minimize stress:

- Minimize Protocol Duration: Reduce the time from tissue harvesting to protoplast fixation or lysis as much as possible.

- Validate with Controls: Include a "time-zero" control or validate key findings using an independent method, such as spatial transcriptomics or in situ hybridization [21].

- Consider Nuclei: If stress responses remain a persistent problem, switching to a nuclei-based protocol may be necessary to capture a more native transcriptional state [4] [23].

I am not capturing certain cell types in my protoplast/scRNA-seq experiment. What could be wrong?

Some cell types are more resistant to enzymatic digestion or may be physically filtered out.

- Recalcitrant Cell Types: Tissues with thick, lignified secondary cell walls (e.g., xylem vessel elements) are often underrepresented in protoplast preparations [4].

- Size Exclusion: Protoplasts from large cells may be excluded by the mandatory 30-40 µm cell strainer used to prevent microfluidic chip clogging [5].

- Solution: Using nuclei isolation can often recover these missing cell types, as the mechanical homogenization process is less biased by cell wall composition and there is no size-based filtering beyond the initial nuclei purification [4] [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Protocol | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Cellulase R10 / Macerozyme R10 | Enzymatic digestion of cellulose and pectin in plant cell walls. | Critical for protoplast yield and viability; concentration and incubation time require optimization for each species and tissue [5]. |

| Mannitol | Osmoticum to maintain osmotic pressure and prevent protoplast bursting. | Standard concentration ranges from 0.4 M to 0.5 M; essential for protoplast integrity [5] [22]. |

| MES Buffer | Maintains stable pH during enzymatic digestion. | Typically used at pH 5.7 to maintain enzyme activity [5]. |

| W5 Solution | Washing and resuspension solution that provides essential ions (Ca²⁺, Na⁺, K⁺). | High Ca²⁺ content helps stabilize protoplast membranes. Note: Ca²⁺/Mg²⁺ must be removed (e.g., by resuspending in mannitol) for some scRNA-seq library preps [5]. |

| Miracloth / Cell Strainers | Filtration to remove undigested tissue debris and cell clumps. | Sequential filtration through 40 µm (or 30 µm) strainers is crucial to obtain a single-cell suspension compatible with microfluidics [5]. |

Optimized Protocols for Protoplast Isolation and scRNA-seq Library Preparation

Protoplast isolation, the process of creating plant cells without cell walls, is a foundational technique for single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) in plant biology. This process enables researchers to investigate cellular heterogeneity, gene regulatory networks, and developmental trajectories at an unprecedented resolution. However, the recalcitrance of cell walls, which vary in composition across species, tissues, and developmental stages, presents a significant technical hurdle. This technical support center synthesizes troubleshooting knowledge and optimized protocols from key model species—Arabidopsis thaliana, Brassica, and pea—to help researchers overcome barriers in protoplast preparation for successful scRNA-seq experiments.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why is protoplast yield low for my specific plant species? Low yield is often due to suboptimal enzyme combinations or digestion times. The cell wall composition of different species requires tailored enzymatic cocktails. A universal two-step digestion protocol has been successfully applied across diverse angiosperm species. This involves an initial digestion with a pectinase-rich buffer to break down the middle lamella, followed by a secondary digestion focused on cellulase activity to hydrolyze the primary cell wall [1].

Q2: My protoplasts have poor viability. What are the main causes? Poor viability can result from osmotic shock, excessive digestion time, or contamination. Using a pre-treatment buffer with balanced osmotic pressure, vacuum infiltrating for 10 minutes, and strictly controlling digestion time to 3-4 hours can significantly increase viability from approximately 78% to over 90% [1]. Furthermore, filtering protoplasts through 70 µm and 40 µm strainers removes damaging debris [24].

Q3: Does the protoplast isolation process itself alter gene expression? The enzymatic digestion process can induce stress responses. However, studies monitoring key epigenetic regulators found that the protoplasting process did not generate significant transcriptomic fluctuations resulting from epigenetic remodeling, unlike wound responses in intact tissues [1]. Nevertheless, it is recommended to filter out protoplasting-induced transcriptional responses in scRNA-seq data by comparing isolated protoplasts with undigested tissues.

Q4: When should I use nuclei instead of protoplasts for plant scRNA-seq? Single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) is advantageous when working with tissues that are difficult to digest (e.g., woody species), when protoplasts are too large for microfluidic devices, or when studying processes where spatial information is lost and cannot be recovered. snRNA-seq avoids the stress responses triggered by cell wall digestion and is compatible with frozen or preserved samples [3] [21] [25].

Q5: How can I prevent contamination during the isolation process? Maintaining aseptic technique is critical. Key practices include: using personal protective equipment (PPE) and biosafety cabinets, sanitizing all equipment and gloves with 70% ethanol before use, cleansing the hood after each session, using Plant Preservative Mixture (PPM) in culture media to target contaminants, and minimizing cell exposure to unsterile environments [26].

Troubleshooting Common Problems

Table 1: Common Protoplast Isolation Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Yield | Inefficient cell wall digestion | Optimize enzyme ratios (e.g., 1% cellulase, 0.5% pectinase, 0.5% macerozyme for Chirita pumila); implement a two-step digestion protocol [1]. |

| Incomplete tissue digestion | Pre-treat samples with balanced osmotic buffer; cut tissue into small pieces (<1mm) to increase surface area [1] [24]. | |

| Poor Viability | Osmotic shock | Use an appropriate osmoticum (e.g., 0.4-0.5 M mannitol) in all solutions; include MES buffer to maintain stable pH [27] [24]. |

| Enzymatic toxicity | Reduce digestion time; purify protoplasts promptly after digestion by centrifugation and washing [24]. | |

| Cell Clumping | Presence of undigested wall fragments | Filter the protoplast suspension sequentially through 70 µm and 40 µm cell strainers [24]. |

| Excessive debris | Use a wide-bore pipette to handle protoplasts gently and avoid mechanical shear [24]. | |

| Failed Transformation | Low membrane fluidity | Apply a heat-shock treatment (e.g., 45-50°C for 5 min) post-PEG transformation to increase fluidity and DNA uptake [1]. |

| Low-quality protoplasts | Use protoplasts with >80% viability and optimize PEG concentration and exposure time [1]. |

Optimized Experimental Protocols

Arabidopsis thaliana Root Protoplast Isolation for scRNA-seq

This protocol is adapted from a demonstrated method for moss and Arabidopsis root protoplasting, optimized for use with the 10x Genomics Chromium system [24].

Key Reagents:

- Solution A: 0.4 M Mannitol, 20 mM MES (pH 5.7), 20 mM KCl, 10 mM CaCl₂, 0.1% BSA.

- Enzyme Solution: 1.25% Cellulase ("ONOZUKA" R-10), 0.1% Pectolyase in Solution A.

Workflow:

- Plant Growth: Sterilize and sow Arabidopsis seeds densely on nylon-mesh screens placed on solidified MS Growth Media. Grow plates vertically under continuous light at 22°C for 4-5 days until roots are 2-3 cm long.

- Root Harvesting: Decant water from the dish. Use a scalpel to slice off roots and collect them.

- Enzymatic Digestion: Place 4 mL of Enzyme solution in a 35 mm dish with a 70 µm strainer inside. Transfer the harvested roots into the strainer. Digest on a rotating platform at 85 rpm for 45-60 minutes at 25°C, agitating 2-3 times.

- Protoplast Purification: Lift the strainer and collect the liquid. Centrifuge the collected solution at 500g for 10 minutes. Discard the supernatant.

- Filtration and Washing: Gently resuspend the pellet in 500 µL of Solution A (no enzymes). Filter the suspension sequentially through a 70 µm strainer, then two 40 µm strainers.

- Final Concentration: Centrifuge the filtered solution at 200g for 6 minutes. Discard the supernatant and resuspend the protoplast pellet in a small volume (30-50 µL) of Solution A.

- Quality Control: Assess protoplast density, purity, and viability (e.g., using Evans blue staining). Aim for >80% viability and little to no debris. Adjust the concentration to 700-1000 protoplasts/µL for loading on the 10x Genomics Controller.

The entire process from root cutting to loading should not exceed 90 minutes to ensure high-quality transcriptomic data [24].

Universal Two-Step Digestion Protocol for Diverse Species

This protocol, established for Chirita pumila and tested on multiple angiosperm organs, provides a framework that can be adapted for species like Brassica and pea [1].

Key Reagents:

- Pretreatment Buffer: 10 mM MES, 0.47 M Mannitol, 10 mM Calcium (pH 5.8).

- Primary Enzyme Buffer: 1% Cellulase, 0.5% Pectinase, 0.5% Macerozyme in pretreatment buffer.

- Secondary Enzyme Buffer: 1.2% Cellulase, 0.4% Macerozyme.

Workflow:

- Pretreatment: Apply the pretreatment buffer to tissue samples under vacuum infiltration for 10 minutes. This significantly enhances protoplast stability and viability [1].

- Primary Digestion: Incubate pretreated tissues in the Primary Enzyme Buffer for 3-4 hours.

- Secondary Digestion: Replace the solution with the Secondary Enzyme Buffer and incubate for an additional 60-90 minutes. This step effectively dissociates incompletely hydrolyzed tissues and increases yield.

- Protoplast Regeneration: For whole plant regeneration, immobilize protoplasts in a thin alginate layer using a culture density of 1 × 10^6 protoplasts/mL. The entire process from callus formation to de novo root organogenesis can be completed within 15 weeks in optimal conditions for regenerable species like Arabidopsis Wassilewskija (Ws-2) [27].

Figure 1: Universal two-step protoplast isolation workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Protoplast Isolation and Their Functions

| Reagent | Function | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Osmoticum | Maintains osmotic balance to prevent protoplast bursting; provides a stable environment during and after cell wall removal. | Mannitol (0.4-0.5 M), Sucrose (0.6 M) [1] [27] [24]. |

| Cellulase | Degrades cellulose microfibrils, the primary structural component of the plant cell wall. | Cellulase R-10 ("ONOZUKA") [24], Celluclast 1.5 L [27]. |

| Pectinase | Breaks down pectin in the middle lamella, the adhesive between plant cells, enabling tissue dissociation. | Pectolyase [24], Pectinex Ultra SP-L [1]. |

| Macerozyme | A pectinase and hemicellulose-degrading enzyme that macerates plant tissues. | Macerozyme R-10 [1]. |

| Buffer System | Maintains a stable pH throughout the isolation process, which is critical for enzyme activity and cell health. | MES (pH 5.7-5.8) [27] [24]. |

| Calcium Source | Helps maintain membrane integrity and is used for alginate embedding in regeneration protocols. | Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂) [1] [27]. |

| Plant Preservative Mixture (PPM) | A broad-spectrum biocide added to media to prevent microbial contamination (bacteria and fungi) [26]. | PPM [26]. |

Species-Specific Considerations and Protocol Adaptation

Successful protoplast isolation requires careful adaptation of universal principles to the specific biology of the target species.

Figure 2: Protocol adaptation relationships across species.

- Arabidopsis thaliana: As a model organism, it has well-optimized protocols. The ecotype matters; for example, Wassilewskija (Ws-2) has shown higher protoplast regeneration potential than Columbia (Col-0) [27]. Standard root protoplast isolation uses a combination of Cellulase and Pectolyase [24].

- Brassica species: Being closely related to Arabidopsis, protocols are often transferable with minor adjustments. The key is to consider the specific organ (leaf, stem, root) and its developmental stage, as cell wall composition varies accordingly.

- Pea (Pisum sativum): As a lesser-studied species for scRNA-seq, it requires more extensive optimization. Starting with the universal two-step protocol [1] and systematically varying enzyme concentrations and digestion times is recommended. Given its more complex tissue structure, ensuring thorough tissue cutting and vacuum infiltration is crucial for consistent yields.

Mastering species-specific protoplast isolation is a critical step toward democratizing the application of scRNA-seq in plant biology. While foundational protocols from models like Arabidopsis provide an excellent starting point, success with new species hinges on systematic troubleshooting and optimization of key parameters: enzyme cocktails, osmotic stability, and viability maintenance. The growing toolkit, including universal digestion protocols and the alternative of single-nuclei RNA-seq, empowers researchers to tackle an ever-wider array of plant species. These advances will ultimately fuel a deeper understanding of cellular function and regulation across the plant kingdom, with significant implications for crop improvement and fundamental plant science.

In plant single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) research, the quality of the starting biological material is paramount. The process begins with the isolation of intact, viable protoplasts, which are plant cells that have had their cell walls removed. The enzymatic cocktail used for cell wall digestion is the most critical factor in this initial step, directly impacting protoplast yield, viability, and the success of downstream scRNA-seq applications. An optimized enzyme solution ensures the efficient release of protoplasts without compromising cellular integrity or introducing stress-induced transcriptional changes that could confound scRNA-seq data interpretation. This guide addresses the common challenges and troubleshooting strategies for optimizing cellulase and macerozyme concentrations—the core components of most protoplast isolation protocols—to generate high-quality protoplasts suitable for sensitive single-cell genomic analyses.

FAQ: Core Concepts for Practitioners

Q1: Why is optimizing cellulase and macerozyme concentration critical for protoplast preparation aimed at scRNA-seq?

The optimization of cellulase and macerozyme is fundamental because these enzymes directly determine the efficiency of cell wall digestion and the physiological state of the resulting protoplasts. For scRNA-seq, the objective is not merely to liberate cells but to do so in a way that preserves their native transcriptional profile. Inadequate digestion, due to low enzyme concentrations, results in low protoplast yield and potential bias towards specific cell types that are more easily released [28]. Conversely, excessive enzyme concentrations or prolonged digestion times can damage the plasma membrane, induce stress responses, and trigger aberrant gene expression, which directly corrupts the transcriptional data obtained from scRNA-seq [17]. Therefore, a balanced optimization is essential to maximize yield and viability while minimizing transcriptional artifacts.

Q2: What are the primary functions of cellulase versus macerozyme in a protoplast isolation cocktail?

The enzymes cellulase and macerozyme have distinct yet complementary roles in breaking down the plant cell wall:

- Cellulase targets cellulose, the primary structural polysaccharide forming the microfibril framework of the cell wall. Its action is crucial for degrading the wall's main load-bearing network [29] [17].

- Macerozyme is a pectinase-rich mixture that primarily degrades pectin, a polysaccharide that acts as the "cement" in the middle lamella, holding adjacent plant cells together [29] [17]. Its action is vital for tissue dissociation and the release of individual cells.

In practice, macerozyme works to separate cells from each other, while cellulase works to remove the remaining wall from each cell. A combination of both is typically required for efficient protoplast isolation [29].

Q3: A standard enzyme cocktail isn't working for my specific plant species. What factors should I consider optimizing?

Plant cell wall composition varies significantly across species, tissues, and growth conditions. If a standard protocol fails, a systematic optimization of the following factors is recommended, as detailed in Table 1:

- Enzyme Concentrations: Titrate the levels of cellulase and macerozyme. Harder tissues often require higher concentrations [28] [17].

- Osmoticum Concentration: The osmotic pressure, maintained by mannitol or sorbitol, is crucial for preventing protoplast lysis or shrinkage [28] [17].

- Enzymatic Digestion Time: The duration of tissue exposure to the enzymes must be balanced to achieve complete digestion without harming the protoplasts [28].

- Tissue Source and Age: Young, actively growing leaves or hypocotyls are generally ideal due to their thinner cell walls [17].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues and Solutions

Problem: Low Protoplast Yield

- Potential Cause 1: Insufficient concentration of cellulase and/or macerozyme.

- Solution: Incrementally increase the enzyme concentrations. For example, in Populus simonii × P. nigra, an optimized system used 2.5% cellulase R-10 and 0.6% macerozyme R-10 [28].

- Potential Cause 2: Inadequate digestion time.

- Potential Cause 3: Suboptimal osmotic pressure.

- Solution: Adjust the concentration of the osmoticum (e.g., mannitol). Test a range from 0.5 M to 0.8 M, as the optimal concentration was found to be 0.8 M for poplar leaves [28].

Problem: Poor Protoplast Viability

- Potential Cause 1: Enzyme concentrations are too high, causing damage to the cell membrane.

- Solution: Reduce the concentration of cellulase and macerozyme and/or shorten the digestion time.

- Potential Cause 2: Osmotic imbalance leads to protoplast bursting or collapse.

- Solution: Verify the osmolarity of all solutions. Ensure the mannitol concentration is correctly prepared and consistent across all steps from digestion to washing and resuspension [17].

- Potential Cause 3: Mechanical stress from rough handling or centrifugation.

Problem: Incomplete Tissue Digestion with Visible Clumps

- Potential Cause 1: Deficiency in pectin-degrading activity.

- Solution: Increase the concentration of macerozyme, which is rich in pectinase. Alternatively, consider supplementing with other pectinase enzymes or pectolyase, as was included at 0.3% in the optimized poplar protocol [28].

- Potential Cause 2: Ineffective enzyme penetration into the tissue.

- Solution: Ensure the plant tissue is finely sliced or chopped to increase the surface area for enzyme action [28].

Optimized Protocol and Data Tables

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Enzyme Optimization

The following procedure, adapted from published studies [28] [29], provides a robust starting point for optimizing protoplast isolation from leaf tissue.

- Plant Material Preparation: Harvest 0.2-0.5 g of young, fully expanded leaves from healthy plants. Using a sharp blade, remove the midrib and slice the leaves into thin strips (0.5-1 mm) to maximize surface area for enzyme contact.

- Enzyme Solution Preparation: Freshly prepare the enzyme solution in a petri dish. A basic, widely applicable formulation includes:

- 1.5% (w/v) Cellulase ONOZUKA R-10

- 0.5% (w/v) Macerozyme R-10

- 0.6 M Mannitol (for osmotic support)

- 10 mM CaCl₂ (for membrane stability)

- 20 mM MES buffer (pH 5.8)

- Filter-sterilize the solution using a 0.45 μm syringe filter.

- Enzymatic Digestion: Transfer the sliced leaf tissue into the enzyme solution, ensuring the tissue is fully immersed. Seal the plate and incubate in the dark with gentle shaking (40-80 rpm) at 25-27°C for 3-6 hours. The optimal time is species-dependent.

- Protoplast Purification:

- After digestion, gently swirl the mixture and filter the suspension through a 40-70 μm nylon mesh into a 50 mL centrifuge tube to remove undigested tissue and debris.

- Centrifuge the filtrate at 100-200 x g for 2-5 minutes to pellet the protoplasts.

- Carefully remove the supernatant and resuspend the pellet in a washing solution (e.g., W5 solution: 125 mM CaCl₂, 5 mM KCl, 154 mM NaCl, 2 mM MES, pH 5.8).

- Repeat the washing step once.

- Yield and Viability Assessment:

- Yield: Count the protoplasts using a hemocytometer under a microscope. Calculate yield as protoplasts per gram of fresh weight tissue (protoplasts/gFW).

- Viability: Mix a small aliquot of protoplasts with an equal volume of 0.4% (w/v) Trypan Blue stain. Viable protoplasts will exclude the dye and remain clear, while dead cells will take up the blue color. Calculate viability as the percentage of unstained protoplasts out of the total counted.

Quantitative Data for Enzyme Optimization

Table 1: Optimized Enzyme Cocktail Formulations from Various Plant Species

| Plant Species | Tissue | Cellulase R-10 (%) | Macerozyme R-10 (%) | Additional Enzymes | Mannitol (M) | Digestion Time (Hours) | Yield (protoplasts/gFW) | Viability (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Populus simonii × P. nigra [28] | Leaf | 2.5 | 0.6 | 0.3% Pectolyase Y-23 | 0.8 | 5 | 2.0 x 10⁷ | >98 |

| Physcomitrium patens [29] | Protonemal tissue | 1.5 | 0.5 | - | 0.5 | 3 | 1.8 x 10⁶* | - |

| Solanum genus (General guidance) [17] | Leaf/Hypocotyl | 1.5 - 2.0 | ~0.5 | (Pectinase often included) | 0.4 - 0.6 | 4 - 6 | Variable | Variable |

Yield for moss is estimated from the protocol description. *Specific concentration for Macerozyme in Solanum not provided; 0.5% is a common standard.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Matrix: Symptoms, Causes, and Adjustments

| Observed Problem | Likely Cause | Recommended Adjustment |

|---|---|---|

| Low yield, intact tissue | Low enzyme activity / concentration | Increase cellulase and macerozyme by 0.5% increments |

| Low yield, tissue macerated | Osmotic imbalance / mechanical stress | Increase mannitol concentration; gentler handling |

| High yield, low viability | Enzyme toxicity / over-digestion | Reduce digestion time or enzyme concentration |

| Cell clumping, few free protoplasts | Insufficient pectin degradation | Increase macerozyme concentration or add pectolyase |

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision-making process for optimizing an enzyme cocktail, from problem identification to solution validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Protoplast Isolation and Their Functions

| Reagent | Function / Role in Protoplast Isolation | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Cellulase ONOZUKA R-10 | Hydrolyzes cellulose, the primary component of the plant cell wall, enabling its breakdown. | Used at 1.5% for moss [29] and 2.5% for poplar [28]. |

| Macerozyme R-10 | Degrades pectins in the middle lamella, dissociating tissues and releasing individual cells. | Used at 0.5% for moss [29] and 0.6% for poplar [28]. |

| Mannitol | Non-penetrating osmoticum; maintains osmotic pressure to prevent protoplast lysis and stabilize them during and after isolation. | Optimal concentration was 0.8 M for poplar [28]; commonly used between 0.5-0.6 M for other species. |

| Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂) | Divalent cations help stabilize the plasma membrane of the newly exposed protoplasts. | Included at 10 mM in the digestion solution for poplar [28] and in wash solutions. |

| MES Buffer | Maintains the optimal acidic pH (typically 5.8) for the activity of the cell wall-degrading enzymes. | Used at 20 mM in the enzyme solution for poplar [28]. |

| Pectolyase Y-23 | A potent pectinase often supplemented to enhance the degradation of tough plant tissues. | Added at 0.3% in the optimized poplar protocol to improve efficiency [28]. |

Step-by-Step Guide to Protoplast Purification and Viability Assessment

This guide provides detailed protocols and troubleshooting advice for the critical steps of protoplast purification and viability assessment. These steps are essential for ensuring the success of downstream applications, particularly single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), where the quality and vitality of protoplasts directly impact data quality.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary methods for purifying protoplasts after enzymatic digestion? The main purification methods are centrifugation-based, each exploiting differences in density:

- Sedimentation (Centrifugal Precipitation): Protoplasts are pelleted at the bottom of a tube. It yields high protoplast numbers but may cause mechanical damage [30].

- Floating Method: Protoplasts float to the surface of a hypertonic sucrose solution during centrifugation, effectively separating them from debris [30].

- Interface Method (Density Gradient Centrifugation): A multi-step gradient of solutions like sucrose or mannitol is used. Viable, intact protoplasts will collect at the interface between solutions of different densities, providing a high-purity fraction [30].

Q2: How can I quickly and accurately assess the viability of my isolated protoplasts? The most common and effective method is fluorescence staining with Fluorescein Diacetate (FDA).

- Principle: Non-fluorescent FDA passively crosses the membrane of living cells. Intracellular esterases hydrolyze FDA into fluorescein, which is fluorescent and accumulates in cells with intact membranes. Dead cells cannot perform this conversion.

- Protocol: Incubate a protoplast sample with FDA (e.g., a final concentration of 0.01-0.1%) for a few minutes. Observe under a fluorescence microscope. Viable cells will show bright green fluorescence, while dead cells will not [1] [31].

- Alternative Probes: Rhodamine 123 can be used to monitor mitochondrial membrane potential and thus cellular activity, providing another indicator of viability [1].

Q3: I am getting a low yield of viable protoplasts. What could be going wrong? Low yield and viability are often linked to the isolation and purification process. Key factors to check are:

- Enzyme Combination and Concentration: The ratio of cellulase, macerozyme, and pectinase is critical and may require optimization for your specific plant species and tissue [1] [30].

- Osmotic Pressure: The osmotic stabilizer concentration must be maintained throughout the entire process to prevent protoplast bursting or shrinkage [1] [17].

- Digestion Time: Over-digestion can damage protoplasts. The optimal duration (often 3-6 hours) must be determined empirically [1] [30].

- Centrifugation Force: Excessive g-force during purification can rupture protoplasts. Use low speeds (e.g., 100 × g for 5-10 minutes) [32].

Q4: My protoplasts appear viable after staining, but they are not dividing in culture. Why? High initial viability does not guarantee regenerative capacity. This issue can stem from:

- Stress from Enzymatic Digestion: The digestion process itself triggers significant transcriptional stress responses that can impair future development [4].

- Epigenetic Changes: Though some studies show key epigenetic regulators remain stable [1], the process may still induce subtle changes affecting cell division.

- Culture Conditions: The osmotic pressure, plant growth regulators, and nutrient composition of the culture media must be meticulously optimized for regeneration, which is often a multi-stage process [32].

Troubleshooting Guide

The following table outlines common problems, their potential causes, and recommended solutions.

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Protoplast Yield | Inefficient cell wall digestion; incorrect enzyme cocktail. | Optimize enzyme types and concentrations (e.g., 1-2% cellulase, 0.5-1% pectinase/macerozyme); use younger, vigorously growing tissues [1] [30] [17]. |

| Low Protoplast Viability | Osmotic shock; over-digestion; mechanical damage. | Maintain consistent osmotic pressure with 0.4-0.6 M mannitol/sorbitol; reduce digestion time; use gentle centrifugation (100-200 × g) [1] [30] [32]. |

| Excessive Cellular Debris | Incomplete filtration; tissue not fully digested. | Filter suspension through a 40-100 μm mesh post-digestion; consider a secondary digestion step for stubborn tissues [1] [30]. |

| Protoplasts Bursting | Hypotonic solution; osmotic imbalance. | Ensure all solutions contain the correct concentration of osmoticum (e.g., mannitol); verify the osmolarity of all buffers [30] [17]. |

| Poor Regeneration | Physiological stress from isolation; suboptimal culture media. | Use a multi-stage media regimen with adjusted plant growth regulators; pre-treat plant material with dark or cold incubation to enhance viability [30] [32]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Purification of Protoplasts via Floating Method

This method is effective for separating viable protoplasts from debris and dead cells.

- Filtered Suspension: After enzymatic digestion, filter the protoplast mixture through a 40-100 μm nylon mesh into a sterile tube to remove undigested tissue clumps [30].

- Centrifuge: Centrifuge the filtrate at a low speed (e.g., 100 × g for 10 minutes) to pellet the protoplasts and debris [32].

- Resuspend: Gently resuspend the pellet in a small volume of W5 solution or a mannitol-based washing solution and place on ice for 30 minutes. During this step, viable protoplasts may rise to the top [32].

- Purify: Carefully collect the band of floated protoplasts from the surface using a pipette.

- Wash: Resuspend the collected protoplasts in a fresh washing solution and centrifuge again at 100 × g for 5 minutes to wash. Repeat if necessary [32].

- Resuspend for Use: Resuspend the final, purified protoplast pellet in an appropriate volume of mannitol-based solution or culture medium for downstream applications.

Protocol 2: Viability Assessment Using Fluorescein Diacetate (FDA)

This is a standard and reliable method for quantifying the percentage of living protoplasts.

- Prepare FDA Stock Solution: Dissolve FDA in acetone to create a stock solution (e.g., 5 mg/mL). This stock can be stored at -20°C.

- Stain Protoplasts: Add the FDA stock solution to a protoplast suspension to achieve a final working concentration of approximately 0.01% (e.g., 2 μL of stock per 1 mL of protoplast suspension). Mix gently and incubate in the dark at room temperature for 5-15 minutes [1] [31].

- Observe Under Microscope: Place a drop of the stained protoplast suspension on a microscope slide.

- Observe using a fluorescence microscope with a blue light excitation filter (typically around 490 nm).

- Viable cells will display bright green fluorescence in their cytoplasm.

- Non-viable cells will remain non-fluorescent.

- Calculate Viability: Count the number of fluorescent (live) and non-fluorescent (dead) cells across several fields of view. Calculate the viability percentage using the formula: Viability (%) = (Number of fluorescent cells / Total number of cells counted) × 100 [1].

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential materials and reagents for protoplast purification and viability assessment are listed below.

| Reagent | Function | Example Usage in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Cellulase | Hydrolyzes cellulose, the primary component of the plant cell wall. | Used at 1-2% (w/v) in enzyme solution to break down the cell wall matrix [1] [17]. |

| Macerozyme / Pectinase | Degrades pectin in the middle lamella, separating cells from each other. | Used at 0.5-1% (w/v) in combination with cellulase [1] [32]. |

| Mannitol / Sorbitol | Osmotic stabilizer. Prevents protoplasts from bursting by maintaining osmotic balance. | Used at 0.4-0.6 M in all solutions during isolation, purification, and initial culture [32] [17]. |

| Fluorescein Diacetate (FDA) | Vital fluorescent dye. Converted to fluorescent fluorescein only in living cells. | Used at ~0.01% final concentration for viability staining [1] [31]. |

| Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂) | Stabilizes the plasma membrane and facilitates protoplast fusion. | Commonly included in enzyme and washing solutions (e.g., 1-10 mM) [32] [17]. |

| MES Buffer | Maintains a stable pH during the enzymatic digestion process. | Added to the enzyme solution, typically at 10 mM, pH 5.7 [32]. |

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Protoplast Purification and Viability Workflow

This diagram outlines the core workflow from tissue to purified, viable protoplasts, highlighting the three main purification pathways.

Protoplast Viability Assessment Logic

This logic diagram illustrates the decision-making process during Fluorescein Diacetate (FDA) staining, showing how cell physiology determines the staining outcome and final viability count.

Adapting Library Construction Methods (10x Genomics, SMART-seq2) for Plant Protoplasts

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) represents a transformative technology for investigating cellular heterogeneity, developmental trajectories, and gene regulatory networks in complex biological systems. For plant researchers, adapting established library construction methods like 10x Genomics Chromium and SMART-seq2 to work with protoplasts presents unique technical challenges. This technical support center addresses the specific issues users encounter during plant protoplast preparation and subsequent scRNA-seq library construction, providing targeted troubleshooting guidance framed within the broader context of optimizing plant single-cell research.

Core Concepts and Technical Background

Understanding Your Biological Sample: Protoplasts vs. Nuclei

A fundamental consideration in plant scRNA-seq is whether to work with protoplasts (whole cells without cell walls) or isolated nuclei. Each approach has distinct advantages and limitations that significantly impact experimental outcomes [21].

Protoplast-Based Approaches:

- Provide the complete cellular transcriptome, including both nuclear and cytoplasmic mRNAs [21]

- Can induce artificial stress responses due to the enzymatic digestion required to remove cell walls [21]

- Often suffer from cell-type bias as some plant tissues (especially those with secondary cell walls) are difficult to digest completely [33]

- Compatibility with microfluidic devices can be limited by the large size of some plant protoplasts [21]

Nuclei-Based Approaches (snRNA-seq):

- Bypass challenges associated with cell wall digestion [33]

- Enable work with frozen tissues and difficult-to-dissociate cell types [21]

- Capture only the nuclear transcriptome, potentially missing key biological processes involving cytoplasmic mRNA [21]

- Generally provide fewer unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) and detected genes per biological entity [21]

Table 1: Comparison of Biological Entity Selection for Plant scRNA-seq

| Feature | Protoplasts | Nuclei |

|---|---|---|

| Transcriptome Coverage | Nuclear + cytoplasmic | Primarily nuclear |

| Sample Compatibility | Fresh tissues, limited species | Fresh & frozen tissues, broader species |

| Technical Artifacts | Digestion-induced stress | Potential nuclear RNA leakage |

| Cell Type Bias | High (due to differential digestion) | Lower |

| Protocol Optimization | Species and tissue-specific | More universally applicable |

Technology Selection: 10x Genomics vs. SMART-seq2

The choice between droplet-based (10x Genomics) and full-length (SMART-seq2) scRNA-seq methods involves important trade-offs for plant protoplast research [34].

10x Genomics Chromium (3' end counting):

- Uses microfluidic partitioning to create Gel Beads-in-emulsion (GEMs) containing barcoded oligonucleotides [35]

- Enables high-throughput analysis of thousands of cells simultaneously [36] [35]

- Provides cellular indexing through barcoded beads [35]

- Well-suited for large-scale cell type identification and population studies

SMART-seq2 (Full-length transcript coverage):

- Provides full-length transcript coverage, enabling isoform usage analysis [34]

- Typically processes fewer cells but with greater sequencing depth per cell

- Superior for detecting low-abundance genes and transcript variants [34]

- Requires fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) for cell isolation [34]

Table 2: Technical Comparison of scRNA-seq Methods for Plant Protoplasts

| Parameter | 10x Genomics | SMART-seq2 |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput | High (thousands to millions of cells) [35] | Low to medium (hundreds of cells) |

| Transcript Coverage | 3' end only [35] | Full-length [34] |

| Cell Isolation | Microfluidic partitioning [36] | FACS or manual picking [34] |

| UMI Incorporation | Yes [35] | No [34] |

| Cost per Cell | Lower | Higher |

| Ideal Application | Cell atlas construction, population heterogeneity | Deep transcriptional characterization, isoform analysis |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guides

Protoplast Preparation and Quality Control

Q1: My protoplast viability is low after isolation. What are the critical factors to improve viability?

Low protoplast viability typically results from issues during cell wall digestion. Key optimization points include:

- Enzyme Composition and Osmolarity: Ensure proper enzyme mixtures (cellulase, pectinase, hemicellulase) and maintain correct osmotic pressure throughout digestion [21]

- Digestion Time: Optimize digestion duration to minimize stress – shorter times may yield healthier protoplasts

- Tissue Age and Type: Younger tissues generally yield more viable protoplasts; adjust protocols for different tissue types [21]

- Temperature: Perform digestion at room temperature or slightly below to reduce metabolic stress

- Handling Technique: Use wide-bore pipettes to minimize shear forces during protoplast manipulation

Q2: I'm observing cell-type bias in my protoplast populations. How can I achieve better representation?

Cell-type bias is common in protoplast studies due to differential sensitivity to digestion [21] [33]. Mitigation strategies include:

- Combined Mechanical and Enzymatic Digestion: Gently disrupt tissues mechanically before enzymatic treatment

- Sequential Digestion: Use shorter digestion cycles with collection of released protoplasts at intervals

- Nuclei Isolation Alternative: Consider switching to nuclei isolation for more uniform cell type representation [33]

- Validation: Use cell-type-specific markers to quantify representation and optimize accordingly

Library Construction and Method Adaptation

Q3: How do I adapt the 10x Genomics Chromium workflow for plant protoplasts, given their larger size and different properties?

Plant protoplasts require specific adaptations for droplet-based systems:

- Protopst Size Filtering: Pre-filter protoplasts to ensure they fall within the compatible size range for microfluidic chips (typically <40μm diameter) [21]

- Loading Concentration Optimization: Due to larger size, you may need to adjust cell loading concentrations; follow manufacturer recommendations but expect to optimize empirically [36]

- Buffer Compatibility: Ensure protoplast resuspension buffers are compatible with the 10x Chemistry – avoid viscous solutions that might clog microfluidic chips

- Pressure Optimization: The 10x Chromium Controller may require pressure adjustments for plant protoplasts [36]

Q4: What are the key considerations when using SMART-seq2 with plant protoplasts?

SMART-seq2 implementation with protoplasts requires attention to:

- Cell Lysis Conditions: Optimize lysis buffer composition to effectively break plant membranes without degrading RNA

- Reverse Transcription Efficiency: Plant protoplasts may contain compounds that inhibit reverse transcription; include appropriate additives

- Amplification Bias: Without UMIs, PCR amplification biases can affect quantification; limit amplification cycles where possible [34]

- Quality Assessment: Use Bioanalyzer or TapeStation to confirm full-length cDNA library quality before sequencing

Technical Challenges and Optimization

Q5: I'm getting high background noise and low gene detection in my plant scRNA-seq data. What could be causing this?

Poor data quality often stems from several potential issues:

- RNA Degradation: Ensure rapid processing after protoplast isolation and use RNase inhibitors

- Excessive Debris: Remove debris through careful filtering (30μm strainers) or gradient centrifugation [37]

- Low Viability: Start with high-viability protoplast preparations (>85% recommended) [37]

- Library Construction Issues: Verify reverse transcription and amplification efficiency through QC steps

- Sequencing Depth: Ensure sufficient sequencing depth – plant genomes may require adjustments to standard recommendations

Q6: How can I handle the high RNA content in chloroplasts and other organelles during plant protoplast scRNA-seq?

Organellar RNA can dominate sequencing libraries in plant protoplast preparations:

- Poly-A Selection: Most scRNA-seq methods use poly-A selection which should exclude non-polyadenylated organellar RNA [37]

- Probe-Based Depletion: Consider using ribosomal RNA depletion kits optimized for plant rRNA

- Bioinformatic Filtering: Remove organellar reads computationally during data processing

- Nuclei Alternative: Isolating nuclei instead of whole protoplasts naturally excludes chloroplast and mitochondrial RNAs [21]

Experimental Workflows and Protocol Guidance

Decision Framework for Plant Protoplast scRNA-seq

The following workflow diagram outlines the key decision points when designing a plant protoplast scRNA-seq experiment:

Comprehensive Protocol: 10x Genomics Chromium Adaptation for Plant Protoplasts

Sample Preparation through Library Construction

Protoplast Isolation (Day 1, 3-4 hours)

- Harvest plant tissue and quickly chop into fine pieces in enzyme solution

- Digest with optimized enzyme mixture (concentration and time vary by species/tissue)

- Filter through 30-40μm mesh to remove undigested debris [37]

- Purify protoplasts by centrifugation through sucrose or Percoll gradient

- Resuspend in appropriate buffer and count using hemocytometer

- Assess viability (>85% recommended) using fluorescent dyes [37]

Quality Control Checkpoints

- Microscopy: Examine protoplast morphology – avoid granular or burst protoplasts

- Concentration: Adjust to 700-1,200 cells/μL targeting 10,000 cells per channel (adjust for recovery expectations) [36]

- Viability Re-check: Confirm viability immediately before loading onto Chromium chip

10x Genomics Library Preparation (Day 1, ~1 hour hands-on)

- Use Chromium Single Cell 3' Reagent Kits following manufacturer protocols with modifications:

- Chip Loading: Load protoplast suspension carefully, accounting for larger size

- Partitioning: Run on Chromium Controller or Chromium X Series [36] [35]

- GEM Generation: Monitor GEM formation – plant protoplasts may require pressure adjustments

- Reverse Transcription: Proceed immediately after partitioning [35]

Post-RT Processing and Library Construction (Day 2, 4-5 hours)

- Break emulsions and purify cDNA

- Amplify cDNA with appropriate cycle number (potential optimization point)

- Fragment and size select cDNA before library construction

- Incorporate sample indices and perform final library QC

Sequencing and Data Analysis

- Sequence on Illumina platform with recommended read lengths (28bp Read1, 91bp Read2, 10bp I7 Index)

- Process data through Cell Ranger pipeline with custom reference if needed

- Visualize and explore data with Loupe Browser [35]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Plant Protoplast scRNA-seq

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Wall Digestion Enzymes | Cellulase, Pectinase, Macerozyme | Protoplast isolation from plant tissues | Concentration must be optimized for each tissue type [21] |

| Osmotic Stabilizers | Mannitol, Sorbitol, KCl | Maintain protoplast integrity during isolation | Concentration typically 0.4-0.6M depending on species |

| Viability Stains | Fluorescein diacetate (FDA), Propidium iodide | Assess protoplast viability and membrane integrity | >85% viability recommended for scRNA-seq [37] |

| RNase Inhibitors | Protector RNase Inhibitor, SUPERase-In | Prevent RNA degradation during processing | Critical during protoplast isolation and lysis |

| 10x Genomics Kits | Single Cell 3' Reagent Kits | Library construction for 3' end counting | Compatible with fresh protoplasts; may require optimization [36] |

| SMART-seq2 Reagents | Template Switching Oligo, SMARTER Oligos | Full-length cDNA synthesis and amplification | Enables isoform-level analysis [34] |